The British Victory Parade procession would take place along the very same street where Adolf Hitler’s troops had held their own victory parade almost five years earlier, on July 27th 1940, following the defeat of Poland and surrender of France.

Now, as the leaders of the Big Three (Truman, Stalin & Churchill) gathered in nearby Potsdam to attend the final Allied conference of the Second World War, some 10,000 men along with tanks, armoured cars, searchlight batteries and artillery formations would march along Berlin’s monumental Charlottenburger Chaussee – reviewed by British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and Ministers Anthony Eden and Clement Attlee, along with Field-Marshals Montgomery, Wilson, Alexander and Allan-Brooke.

The street had been one of Berlin’s finest, a tree-lined boulevard running through the city’s central park towards the Brandenburg Gate. Now many of the trees were suspiciously absent and the street was strewn with rubble, following years of Allied aerial bombardment and the final Soviet ground assault on the city throughout April and May 1945 – the Battle of Berlin.

Oliver Lindsay in his book ‘Once a Grenadier’ described the central Tiergarten at this time as

“…reduced by urgency for firewood to a desert of tree stumps”. Recalling a city where: “many of the statues were scarred by shell fire and headless. The River Spree was choked to death and decay, an open sewer with stagnant and scum-bound waters. Three in every four houses were smashed or gutted. In the British Zone, fewer than ten percent of buildings were undamaged.”

Although the fighting in Europe had by this time officially come to an end, Imperial Japan still remained undefeated in the East. The ‘War in the Pacific’ would rage for another two months as British and American forces and their Allies sought to extinguish the Rising Sun.

On the same day as the British Parade, US President Harry Truman and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill agreed to drop the newly developed atomic bomb on Imperial Japan if they failed to surrender. They chose not to inform Soviet leader Joseph Stalin of their decision during the on-going Potsdam Conference.

Later as the tension of the Cold War increased, Charlottenburg Chaussee would be renamed Straße des 17. Juni in 1953 by the West Berlin authorities to commemorate the People’s Uprising in East Germany on June 17th 1953, when the Red Army and GDR Volkspolizei shot protesting workers.

When Did The 'War In Europe' End?

The ‘War in Europe’ (or the Great Patriotic War as it was known by the Soviets) formally ended at 00:17 am on May 9th 1945 in Berlin, when Soviet Marshal Georgy Zhukov, on behalf of the Supreme High Command of the Red Army, and Air Chief Marshal Tedder, Deputy Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force, accepted the surrender of all German forces from Chief of the General Staff Wilhelm Keitel in Karlshort, Berlin.

This wasn’t the first or only time that the German military had surrendered in the hope of bringing the war to an end.

Although the ‘German Instrument of Surrender’ was signed on May 9th in Karlshorst, it was backdated to 11:01 pm on May 8th due to a previous surrender signed on May 7th in the red brick schoolhouse of the Collège Moderne et Technique de Reims in France – headquarters of the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF).

Allied journalists were restricted from reporting this event by a 36-hour embargo as following objections from the Soviets it was subsequently deemed the official surrender of Nazi Germany should take place in the German capital.

- Previously, on April 29th 1945, German Army Group C Commander in Chief, Heinrich Von Vietinghoff had surrendered to British Field-Marshall Harold Alexander at Caserta, Italy. This was not accepted by the German High Command as their final or absolute surrender. Neither did the Allies see it that way either. It only brought to an end the campaign in Italy.

- On May 2nd 1945, General Helmuth Weidling, commander of the Berlin Defence Area, surrendered his force of 45,000 soldiers to Soviet General Vasily Chuikov after the Russians had finally taken control of the Reichstag building. This served only as the capitulation of German forces in Berlin.

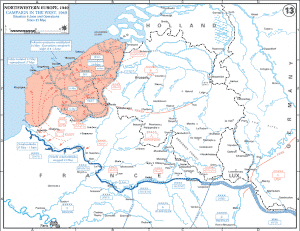

- On May 4th, Admiral Hans Georg. Von Friedeburg tried to surrender the whole of the German forces to Field-Marshal Bernard Montgomery at Luneburg Heath. Whilst the British accepted the surrender of the forces in north-western Europe, those facing the Western allies, Montgomery stated that he could not and would not accept the surrender on behalf of the Russians. The Germans would have to negotiate that directly with the Red Army

Finally, on May 7th the German High Command (led by Colonel-General Alfred Jodl and Admiral Von Friedeburg) tried once more to surrender their entire forces, this time to the Allied Supreme Commander Dwight D. Eisenhower in Reims, France. Whilst Eisenhower accepted the surrender of their western forces, Marshall Zhukov refused to accept this as the German surrender to the Russians as no officer of sufficient rank and authorised by Joseph Stalin was present at the signing of the surrender (Russian General Ivan Susloparov who was present, obviously didn’t count). Only Zhukov was so authorised to accept the unconditional surrender of all German forces, hence the final meeting in Berlin on May 8th when German General Keitel surrendered (effective from May 9th) to Zhukov in Berlin.

British Forces Enter Berlin

It took from the German surrender on May 9th 1945 until July 4th for British troops to actually enter Berlin. And only then because the Soviet finally allowed them into the city to take up the occupation of their part of the city. The division of the Berlin having by this time already been formally agreed upon, in its final form (including the French occupation), at the Yalta conference attended by Roosevelt, Stalin and Churchill in February 1945.

Intent on bringing about a swift end to hostilities in Europe, the Big Three at Yalta had agreed Allied forces would drive hard and fast to the heart of the Third Reich and Adolf Hitler’s seat of power, Berlin: they would then divide both that capital city and the rest of the country. At the time of the agreement, the British and American armies were closer to Berlin than their Russian counterparts. As far as British Field-Marshal Montgomery was concerned, it was a foregone conclusion that he would lead the first of the Allied troops into the Nazi capital.

Stalin, however, had other ideas, despite assuring the other leaders that he was in no hurry to reach Berlin for his own gain. The Soviet leader had discovered that the Germans possessed what he did not. He already knew that the Americans had successfully developed and tested their hydrogen bomb. Stalin believed that the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute in Berlin held enough enriched uranium and scientific know-how for the Russian programme to catch up to the Americans in a much shorter timescale. Whilst the Soviets trailed far behind in their atomic programme, German scientific efforts were much further advanced.

Subsequently, the Soviet leader set two of his best military leaders up against each other in a race to reach and take Berlin, and the atomic prize, before the Western Allies could. As a result Marshals Zhukov and Konev threw whatever troops and munitions they could muster at the defending Germans in order to win that race.

In the meantime, ignorant of the new Russian intentions, Eisenhower decided that Berlin was no longer an important Western Allied objective. He instead believed that there was a greater threat from German forces heading south to Bavaria to organise their last stand. To prevent that, he ordered Montgomery who led the 21st Army Group in the North to cut off the German army, trapping them in or around Denmark and preventing them from moving south.

At the same time, US General George Patton was to head south to Austria, thereby preventing the build-up of Axis troops in the region.

Eisenhower also rightly believed that the Battle for Berlin would be a blood-bath. He had no desire to sacrifice American lives on the purely symbolic objective of seizing the German capital. After all, he knew that Berlin would be well within the Russian sector once the war ended and saw little point in advancing, then withdrawing US troops out of Berlin a few months later.

Montgomery was incensed, but outranked, and had to settle for mopping up the north, where he would accept the formal surrender of German forces in north-western Europe – at Luneburg Heath on May 4th.

Monty And Winnie - The Famous Names Of The British Victory Parade

For two famous men at least, the British Victory Parade in Berlin on July 21st 1945, must have been a bitter-sweet moment.

On May 10th 1940, Winston Churchill became Prime Minister of Britain. At 5 am that same day, the Nazi war machine embarked on the invasion of Western Europe – occupying Holland, Belgium, Luxembourg and forcing the capitulation of France in 46 days.

Facing Hitler’s formidable army at that time was Major-General (later Field Marshal) Bernard Montgomery, the leader of the 3rd Division of the British army.

Also present amongst the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) were the 1st Battalion Grenadier Guards, 1/5th Queens Royal Regiment and the 5th Royal Tank Regiment.

By June 4th 1940, both Churchill, Montgomery and the remains of the BEF had suffered the indignation of being forced out of mainland Europe, to lick their wounds back on English soil. Neither man took the set-back lightly, with Winston Churchill embarking immediately on planning for the defence of Britain. Churchill was to remain British Prime Minister throughout the war, succeeded on July 26th 1945 by Clement Attlee. Montgomery would lead the offensive against the Third Reich in the Middle East and North Africa.

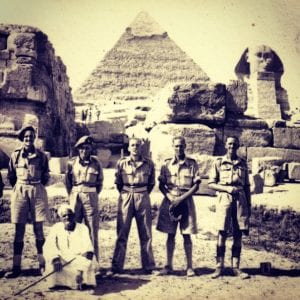

As part of the Eight Army, ‘Monty’ – as he became affectionately known – took over leadership of the 7th Armoured Division, (later to become known as the Desert Rats). Together they marched and fought their way through North Africa, Sicily, Italy and following the D-Day invasion, through North-Western Europe. The ground lost to the Germans in 1940 was slowly being liberated until on May 4th, he took the surrender of German forces in the West, the first Allied commander to do so, followed by the US commander Eisenhower on 7th and Marshal Zhukov on 9th May 1945.

The British Victory Parade on 21st July 1945 was also a special time for Major-General Lewis Lyne. Although his time in action didn’t start until 1942 in the deserts of Africa under Montgomery, he fought through Italy (where he was wounded), Normandy and Northwest Europe. He finally led the 7th Armoured Division into Berlin before becoming the very first British Military-Governor (Commandant) of Berlin.

The Long Road To Berlin & The Troops Of The British Victory Parade

Some regiments fought from the start through to the end of World War Two and were thus rightfully represented at the British Victory Parade. The main contingent was always, or had at some point, been part of the 7th Armoured Division.

-

- The 3rd Royal Horse Artillery was, at the start of the war, stationed in Egypt. It remained in North Africa as part of the 7th Armoured Division and was later involved in the invasions of Italy (at Salerno) and Normandy and the subsequent push through France, Belgium, the Netherlands and finally into Germany. It was they who played a significant part in the British Victory Parade in Berlin on July 21st 1945.

-

- The 5th Royal Horse Artillery had a similar route to the 3rd other than it started its war as part of the BEF and was evacuated out of Dunkirk to defend the UK before heading out to North Africa in 1941.

-

- The 1st Battalion Grenadier Guards were part of the 3rd Division under Montgomery in the BEF in May 1940. They fought a rear-guard action as an infantry unit, delaying the might of the German army as it advanced through Belgium and France. After evacuating to England, they formed part of the defence force aiming to protect the country should an invasion take place and later retrained as an armoured unit. They took part in the invasion of Normandy and fought their way through Northern Europe as part of 30 Corp. During Operation Market Garden, it was they who were the first to cross the bridge at Nijmegen, near Arnhem. They were also involved in the Battle of the Bulge and were invited by Montgomery to take part in the Victory Parade as representatives of the Guards Armoured Division, having first entered the city on July 4th.

-

- The 1/5th Queens Royal Regiment also played a part in the Battle of France before being evacuated through Dunkirk. Following two years providing coastal defence of the Wash and Kent areas they moved to North Africa and joined the 7th Armoured Division. It remained with the Division, fighting through Italy, Normandy and Northern Europe and was one of the first units to enter the German city of Hamburg on May 3rd 1945.

-

- The 2nd Devonshire Regiment, began its war in Malta, remaining there throughout the siege of Malta, finally leaving in 1943 to take part in the invasions of Sicily and Normandy and then as part of the 7th Armoured Division, fighting through the islands of the Netherlands, taking part in the ground support for Operation Market Garden around Arnhem and finally into Germany.

-

- The 3rd Royal Tank Regiment took part in the defence of Calais during the Battle of France in May/June 1940. Against overwhelming odds, it was virtually wiped out. The regiment was rebuilt in the UK and went to North Africa in 1940 before moving in 1941 to Greece where it was decimated once again. A further spell in North Africa was followed in 1943 with a spell in the UK, refitting and retraining before joining allied forces in Normandy. They had a tough time in and around Caen and during its mad dash through France and Belgium, it finally helped liberate the port of Antwerp on September 4th 1944. After a spell in the Ardennes supporting the Battle of the Bulge, the regiment headed to Flensburg on the German/Danish border where their war ended.

-

- The 11th Hussars began their operations in 1939 in North Africa as part of what was to become 7th Armoured Division. It wasn’t until Italy declared war on Britain that their war began in earnest and they remained, fighting in North Africa until they were shipped back to Glasgow in January 1944. They had just 6 months to prepare themselves for the invasion of Normandy and after their arrival on D+6, they fought their way through France, Belgium and into The Netherlands as part of Operation Market Garden. The 8th Hussars played a similar part throughout the war.

-

- The 9th Battalion Durham Light Infantry was part of the BEF during the Battle of France in May 1940 taking part in the counter-attack at Arras, where German General Erwin Rommel was almost killed. Following their evacuation from Dunkirk, they moved into North Africa to join the 7th Armoured Division where they once again took on the might of Rommel and his Afrika Corp. They then took part in the invasion of Sicily before landing on Gold Beach on D-Day and making their way through Northern Europe. The first Victoria Cross to be awarded in World War Two was won by Second Lieutenant Richard Annand of the 2nd Durham Light Infantry on May 15/16th 1940. He was wounded whilst attacking an enemy position alone, out of ammunition, inflicting over 20 German casualties using just hand grenades and then resuming command of his platoon to carry on the fight. He then repeated these same actions once more that day before accepting an order to fall-back but then returning for his wounded batman, pushing him back to safety in a wheelbarrow before collapsing himself.

The 6th and 8th Battalions Durham Light Infantry had a similar battle history to the 9th but were not in attendance for the Victory Parade.

After the war, Field-Marshall Montgomery wrote of the Durham Light Infantry:

“Of all the infantry regiments in the British Army, the DLI was one most closely associated with myself during the war. The DLI Brigade [151st Brigade] fought under my command from Alamein to Germany …It is a magnificent regiment. Steady as a rock in battle and absolutely reliable on all occasions. The fighting men of Durham are splendid soldiers; they excel in the hard-fought battle and they always stick it out to the end; they have gained their objectives and held their positions even when all their officers have been killed and conditions were almost unendurable.”

Also in attendance were the 4th and 621st Field Squadrons and 143rd Field Park Troop (all of the Royal Engineers), a composite battalion from First Canadian Army (the largest unit being the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders of Canada (Princess Louise’s) pipes and drums) and the Royal Air Force and the R.A.F. Regiment.

Notably absent was the 5th Royal Tank Regiment – a unit that had fought throughout the war in the various theatres and served under the 7th Armoured Brigade but wasn’t invited to take part in the British Victory Parade. They were one of the most combat experienced units of the whole of the British Army during World War Two. They were part of the BEF that fought and lost the Battle of France, they played a pivotal role in the North Africa campaign, fought throughout Italy and Northern Europe after landing in Normandy, ending their war just outside Hamburg. Their exclusion from the celebrations may have had more to do with their reputation for failing to conform fully to the King’s Regulation that governed army discipline. They were known amongst other names as the “Filthy Fifth,” due to their often rag-tag appearance.

Beyond The British Victory Parade - Not the Only Celebration

The British Victory Parade on July 21st 1945 would be the biggest and most significant of its kind but was not the first time in 1945 that the British had organised a parade in the German capital.

-

- On July 2nd, the first British troops entered the city and took up residence in the barracks at Spandau.

-

- On July 4th, in the Spandau district of Berlin, the British celebrated officially taking over their zone of the city. According to a young officer in the 11th Hussars, Richard Brett-Smith, it was a “tired and dusty” affair, more like “a sober liberation than a triumphant entry into a conquered city”

-

- On July 6th, the Union Jack flag was raised at the side of the Franco-Prussian War Memorial on the Grosser Stern in the centre of the Tiergarten.

-

- On July 12th, Field-Marshall Montgomery led a ceremony investing Soviet Marshal Zhukov with the Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath (GCB) And Marshal Rokossovsky with the Knights Commander of the Order of the Bath (KCB).

-

- On July 13th the 7th Armoured Division plus the Grenadier Guards marched past the four Allied commanders of Berlin: Major-General Lyne (GB), Colonel-General Gorbatov (USSR), Major-General Floyd Parks (US) and General de Beauchesne (France).

-

- On 15th July, Winston Churchill was greeted by a guard of honour when he arrived at Gatow airport in Berlin for the Potsdam Conference.

The British Victory Parade - The After Party

By 11.15 am the parade had finished and Churchill left to officially open the armed services “Winston Club” – formerly the Kabarett der Komiker – on the Kurfürstendamm at its junction with Lehniner Platz. Here he addressed the 7th Armoured Division and, in particular, the 11th Hussars:

“Now I have only a word more to say about the Desert Rats, They were the first to begin. The 11th Hussars were in action in the desert in 1940 and ever since you have kept marching steadily forward on the long road to victory. Through so many countries and changing scenes, you have fought your way. It is not without emotion that I can express to you what I feel about the Desert Rats.

Dear Desert Rats! May your glory ever shine! May your laurels never fade! May the memory of this glorious pilgrimage of war which you have made from Alamein, via the Baltic to Berlin never die!

It is a march unsurpassed through all the story of war so as my reading of history leads to believe. May the fathers long tell the children about this tale. May you all feel that in following your great ancestors you have accomplished something which has done good to the whole world; which has raised the honour of your country and which every man has the right to feel proud of”.

–

To learn more about the British Victory Parade, the Allied Victory Parade that followed it – the Potsdam Conference – and Berlin’s Third Reich period – consider joining one of our Third Reich and Cold War private tours.

–

If you’ve enjoyed reading this article, consider booking one of our private guided tours of Berlin.

Our Related Tours

Want to learn more about the Battle of Berlin? Check out our Battle of Berlin tours to explore what remains of this important urban battlefield.

To learn more about the history of Nazi Germany and life in Hitler’s Third Reich, have a look at our Capital Of Tyranny tours.

Sources

Antill, P., Battle for Berlin: April-May 1945, http://www.historyofwar.org/article/battles_berlin.html

Delaforce, P. Montys Northern Legions: 50th Northumbrian and 15th Scottish Divisions at War 1939–1945 (London: Sutton Publishing, 2004)

Forty, George, Desert Rats at War (Bristol: Air Sea Media Services, 2014)

Gilbert, Martin (ed.), Churchill – The Power of Words: His Remarkable Life Recounted

Through His Writings and Speeches (London: Bantam Press, 2012)

Lindsay, Oliver, Once a Grenadier (London: Leo Cooper, 1996)

Osborne, Keith, Berlin or Bust (Chester: Keith Osborne, 2000)

Red Kalinka, http://www.redkalinka.com/Russian-Blog/121/_9-May-Victory-Day/

Rogers, Duncan and Williams, Sarah (eds.), On the Bloody Road to Berlin (Birmingham: Helion and Company Ltd, 2005)

Strawson, John, The Battle for Berlin (London: BT Batsford Ltd, 1974)

Urban, Mark, The Tank War (London: Abacus, 2013)

VE Day and the Argylls, https://www.argylls.ca/history/ve-day.html