The encirclement of Berlin by the forces of the Soviet Union, on April 25th 1945, was not the first time that war arrived to the streets of the Nazi capital. Nor could it be said that the opening volleys of Red Army artillery hitting the city on April 20th were the start of Berlin’s physical ruin.

The Battle of Berlin, in many ways, began much earlier.

Capable of inflicting a measure of carnage unprecedented before the early 20th century, the air fleets of the British Royal Air Force and United States Army Air Force had been repeatedly pounding the city since 1940.

Five years before the arrival of Soviet ground forces.

Gradually reducing the blackened heart of the Third Reich to smouldering rubble.

With geography and technology more often than not limiting conflict to the frontiers of any belligerent state – never before in human history had the capital of an enemy power been subjected to so much; and from such a distance.

Over the course of these five years, Berliners would endure more than 350 independent air raids.

Some, like those on November 22nd 1943 carried out by the British and February 3rd 1945 by the US forces – would remain etched into the minds of the city’s residents for their ferocity and randomness long after the final shots of the war had been fired. For as predictable as these raids would become in their regularity, they would remain distinctly inaccurate when measured by their precision and capability of hitting valuable targets.

Modern estimates suggest that only one in five of all the bombs dropped during the Second World War came within five miles of their intended targets.

The Soviet had in-fact already attacked Berlin well before 1945 – when their own air force flew missions to the Nazi capital – although these were dwarfed in size and effectiveness by the combined Anglo-American raids.

In almost all instances it would be the everyday residents and infrastructure of the city, as much as the munitions factories, government buildings, and military fortifications, that would bear the brunt of the Allied bombardment.

Not much would be different when Soviet long-range artillery eventually came within firing distance of the Nazi capital on April 20th 1945.

Battering what remained of the centre of Berlin into a disfigured and crippled mass.

As relieved as Berliners must have been on April 20th to finally see the last of the Anglo-American raids, the end of one torturous method of destruction would only signal the passage to another.

The thunderous arrival of Stalin’s forces had already begun earlier in the day with the mass pulverisation of the city. Ensuring that the fight for the largest city in the Reich, the nucleus of Hitler’s regime, would be as bloody and contested as possible.

For as the Soviets knew, rubble could provide an impregnable defence.

Just as Berliners would be deathly familiar with the drone of air raid sirens and rumble of allied aircraft – the brutality of urban warfare would already be burned into the consciousness of every one of the 2.5 million Soviet soldiers poised outside the Nazi capital in April 1945.

The cities of Stalingrad and Leningrad – that bore the names of the Soviet leaders – had been viciously contested in battles that ended in decisive Soviet victories – albeit with massive losses – and would serve as rallying cries in the ‘Great Patriotic War’ to expel the fascist invader.

A war which would only end with the Nazi capital taken and the flag of the Red Army flying high over the Reichstag building.

After almost four years of bitter conflict and horrifying loss of life, the forces of the Soviet Union reached the “Gates of Berlin” in April 1945 – and with over six million men and women in uniform bearing down on central Europe and threatening a final confrontation between the Weltanschauung of National Socialism and Stalinist Soviet communism.

The soldiery gathered outside Berlin in preparation for this final engagement was undoubtedly a strange sight, with so many different dialects and languages that officers could often not communicate with their troops.

Varied as much in physical appearance as in battle dress, these troops wearing shades of different uniforms came from every republic of the Soviet Union. Russians and Belorussians, Ukrainians, Karelians, Tartars, Georgians, Kazakhs, Azerbaijanis, Bashkirs, Mordvinians, Irkutsks, Uzbeks, Mongols, and Cossacks. They came on horseback, and on foot, on captured vehicles – and lend-lease American ones too.

The howl of Stalin’s organ, the much feared Katyusha rocket launcher, signalling their arrival, they would bring with them the tools of their trade – PPSh-41 submachine guns and satchel charges, to aid in the gruelling urban combat – even pick-axes and dynamite to blow holes in buildings through which the infantry would advance. Supported by T-34 and IS-II tanks, self-propelled guns such as the SU-76, SU-100, and ISU-152. Teams of horses would drag supplies and wounded.

Hitler’s invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941 – codenamed Operation Barbarossa – had come unannounced and without declaration of war. A violation of the non-aggression treaty that the foreign ministers of the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany, Molotov and Ribbentrop, had orchestrated two years before. That had resulted in the two powers carving up neutral Poland and establishing European ‘spheres of influence’.

The advance of Hitler’s forces into the Soviet Union in violation of the double Faustian pact – the ‘Midnight of the Century’ – had been rapid – with units reaching the outskirts of Moscow by December 1941. After years of contesting territory and some of the bloodiest fighting the world had ever seen – that would leave the bodies of millions in its wake – the Red Army would finally arrive back in Poland in 1944 to confront Nazi Germany within its own original borders.

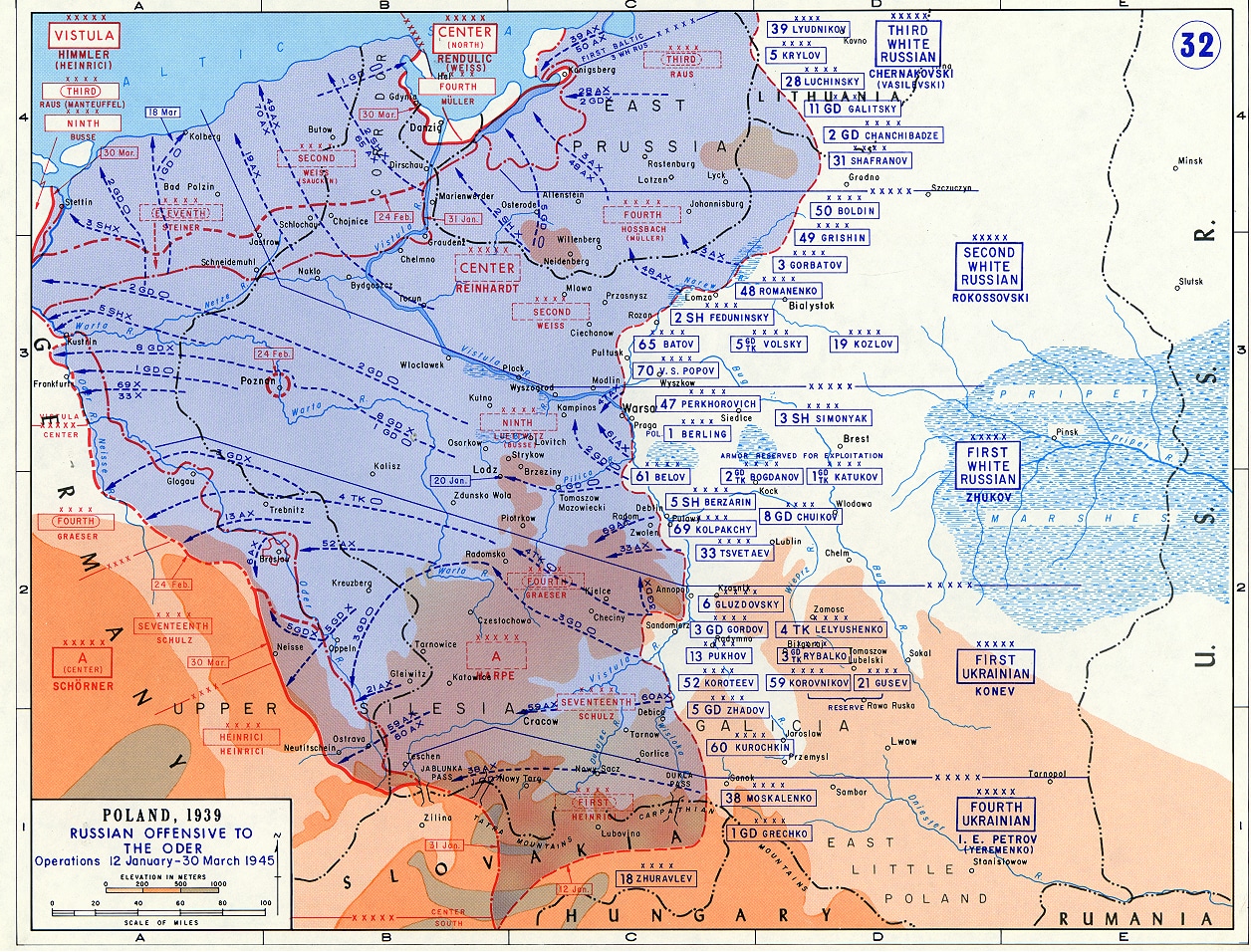

That year, the Soviet Red Army had engaged the forces of the German Wehrmacht in no fewer than ten offensives. Greatly improving its ability to encircle and annihilate vast swathes of Nazi forces as the war progressed. New equipment such as upgraded T-34/85 and IS-II tanks, the role of a decentralised and enhanced Soviet Air Force, and the mobilisation of the Soviet states to a war footing had brought much success.

Time and time again, though, the Red Army would prove that even though its tactics had much improved since the bitter defeats of 1941 and 1942, numerical supremacy would more often than not serve as the common deciding factor in most battles. The Berlin operation would be no different, as masses of troops levelled off to descend on the Nazi capital and overwhelm the vastly outnumbered defenders.

The Vistula-Oder campaign from January 1945, directly preceding the Battle of Berlin, would see the Red Army take Krakow and Katowice, surround Danzig and Königsberg, and march unopposed into Hitler’s abandoned Wolf’s Lair headquarters in Rastenburg on January 27th. The same day, troops of the First Ukrainian Front (322nd Rifle Division, 60th Army) would liberate the Auschwitz death camp.

After having established two bridgeheads across the Vistula that could have seen the Red Army come to the aid of Polish resistance fighting in the Warsaw Uprising, the Polish capital of Warsaw was also finally captured and ‘liberated’ in January 1945, following a six month pause.

All told, some 600,000 Soviet soldiers and officers gave their lives to defeat the Nazi forces occupying present-day Polish territory in the Vistula-Oder campaign.

By January 31st, this Soviet offensive would come to a halt at the ‘Gates of Berlin’ – while the forward troops rested, others were tasked with consolidating territory – mopping up any remaining resistance encircled or bypassed during their advance.

The stage was set for a ferocious battle in the Nazi capital – the largest confrontation between Axis and Allied forces that would take place on German soil.

One where vengeance would be weighed in blood.

However, it would be a mistake to think that the Battle of Berlin was decided entirely within the city itself. Despite the ferocity of the battle, it would be concluded in only 17 days – without the extensive use of siege tactics or an extended period of stalemate.

The opening days of the battle, particularly for the Seelow Heights some 90km to the east, would seal the fate of the city.

This series of 18 posts (including introduction and aftermath) will tell the story of the Fall of Berlin in 1945 – day-by-day – through the eyes of the defenders, the Soviet personnel tasked with attacking the city, but also the millions of civilians who would share the burden.

This final confrontation was a military feat bar none – all told, 402 Red Army personnel were bestowed the USSR’s highest degree of distinction, the title Hero of the Soviet Union (HSU), for their valour in Berlin’s immediate suburbs and in the city itself.

Two hundred thousand people would perish over the space of 17 days of fighting – from the sandy banks of the river Oder, to the final objective on top of the Reichstag, and the capitulation of the forces in the city on May 2nd.

The result would be a decisive Soviet victory – the most symbolic of the war.

The death of Adolf Hitler and the coup de grâce to National Socialism.

When the Western Allies finally arrived in Berlin some two months later, on July 4th, it was to a city unrecognisable to visitors fortunate enough to have witnessed the German capital in its pre-war splendour.

A city that still today bears the scars of the street-by-street, house-by-house, cellar-by-cellar fighting that would become emblematic of the last major offensive of the war.

The Soviet offensive that would begin on April 16th 1945…

**

Our Related Tours

Want to learn more about the Battle of Berlin? Check out our Battle of Berlin tours to explore what remains of this important urban battlefield.

To learn more about the history of Nazi Germany and life in Hitler’s Third Reich, have a look at our Capital Of Tyranny tours.

Bibliography

Beevor, Antony (2003) Berlin: The Downfall 1945 | ISBN 978-0-14-028696-0

Hamilton, Aaron Stephan (2020) Bloody Streets: The Soviet Assault On Berlin | ISBN-13 : 978-1912866137

Kershaw, Ian (2001) Hitler, 1936–1945: Nemesis | ISBN 0-393-04994-9

Le Tissier, Tony (2010) Race for the Reichstag: the 1945 Battle for Berlin | ISBN: 978-1848842304

Le Tissier, Tony(2019) SS Charlemagne: The 33rd Waffen-Grenadier Division of the SS | ISBN: 978-1526756640

Mayo, Jonathan (2016) Hitler’s Last Day: Minute by Minute | ISBN: 978-1780722337

McCormack, David (2017) The Berlin 1945 Battlefield Guide Part I the Battle of the Oder-Neisse | ISBN: 978-1781556078

McCormack, David (2019) The Berlin 1945 Battlefield Guide Part II The Battle of Berlin | ISBN: 978-1781557396

Moorhouse, Roger (2010) Berlin at War | ISBN: 978-0465028559

Ryan, Cornelius (1966) The Last Battle | ISBN 978-0-671-40640-0

Sandner, Harald (2019) Hitler – Das Itinerar, Band IV (Taschenbuch): Aufenthaltsorte und Reisen von 1889 bis 1945 – Band IV: 1940 bis 1945 | ISBN: 978-3957231581

Shirer, William L. The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich | ISBN 978-1451651683.