…(the attack on Berlin)…is developing irresponsibly slowly. If the operation continues like this, it risks losing its momentum and it might die out…”

Soviet Marshal Georgy Zhukov

Commander of the 1st Belorussian Front

“I got a directive from the front commander to cross the river Spree and attack swiftly in the general direction of Vetschau, [Golsen], Baruth, Teltow and the southern outskirts of Berlin […] The march of the 1st Ukrainian Front towards Berlin had begun.”

Soviet General Pavel Rybalko,

Commander of the 3rd Guards Tank Army

–

While Soviet forces continued to push against Army Groups Vistula and Centre some 90km to the east, the millions of residents of Berlin waited to see whether the threadbare remnants of the mighty Wehrmacht could withstand ‘the Red onslaught’.

Or, more simply put, for how long.

The pre-war population of Berlin had been reduced by evacuation, redeployment of labour, and casualties – from a peak of around 4.3 million to between two and two and a half million in April 1945.

Two years earlier, Propaganda Minister of Nazi Germany, Joseph Goebbels – in his capacity of Gauleiter (district leader) of Berlin – had closed schools and organised the evacuation of some one million inhabitants in response to the threat of Allied air raids. With refugees flooding into the Nazi capital from the provinces of East Prussia, Pomerania, and Silesia, in the last year of the war – bearing tales of horror at the hands of the Soviets – Berlin’s population had naturally increased in size. But nothing substantial enough to overburden the city’s robust infrastructure.

Despite its wide streets – that limited the spread of fire from Allied air raids and allowed fire engines to maneuver around rubble – Berlin could boast of being the most heavily bombed city in Germany – if not the world.

But the population had yet to suffer from hunger. Food rationing was somewhat adequate considering the circumstances. Public order was being maintained – with 12,000 police still patrolling the streets – and in spite of the growing destruction of the city municipal transportation remained operational.

Many Berliners later recollecting the calm before the Soviet arrival would emphasise the infection of atrocity stories, brought by the cart-load from the east, about Soviet revenge enacted on the local population – rapes and executions. To others a mood of passive resignation prevailed. Or simply the refusal to believe that things could be so desperate.

And that Ivan could be knocking on the door.

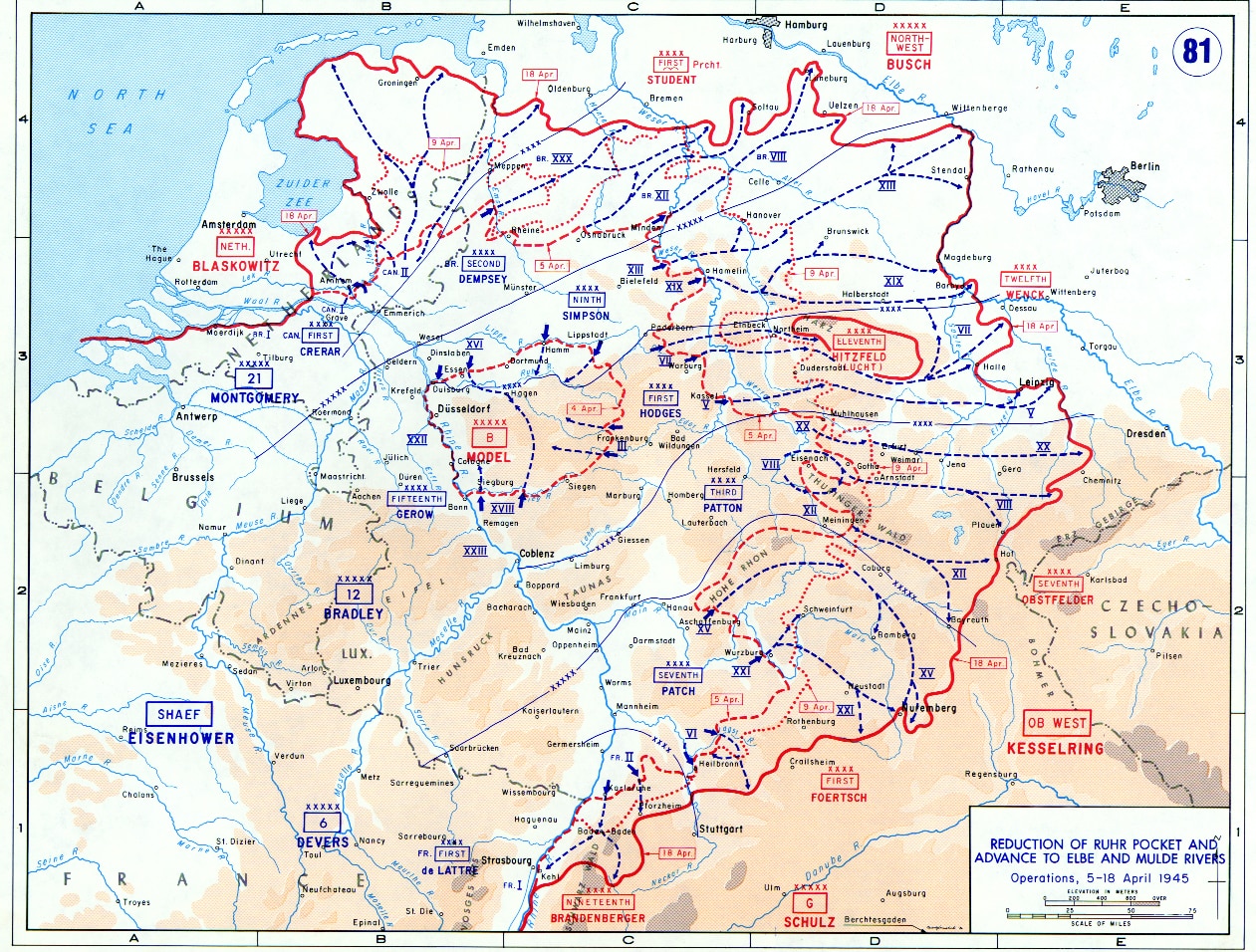

On the western front, British and American forces were also creeping closer to the Nazi capital.

In February 1945, however, following the secret Yalta Conference attended by the leaders of the Big Three (Stalin, Roosevelt, and Churchill), German intelligence had come into the possession of a dossier codenamed ‘Operation Eclipse’ detailing the division of Germany agreed between the victorious allied powers – and outlining the limits of the Allied advance. The next month, Gotthard Heinrici – in his role as head of Army Group Vistula – was presented with a copy of the papers. Poring over the enclosed maps he could easily conclude that – if true – the western allies had agreed upon the Soviets alone taking Berlin, which would later be divided between the three powers, while the British and American forces would drive deep into Germany to reach the Elbe.

His reaction was clear: “Das ist ein Todesurteil” – this is a death sentence.

By mid-April, the Western Allies – overseen by Dwight Eisenhower – had penetrated deep into German territory, claiming over 50% of the country. But to Gotthard Heinrici it would be little consolation that the Western Allies would remain to his rear when the beleaguered forces of Army Group Vistula struggled to absorb the effects of the Soviet assault east of Berlin. Knowledge of Operation Eclipse among the high command would not stop rumours of discord between the Soviets and Western Allies spreading amongst the German population, or the hope that the Americans or British would make it to the capital first spreading amongst Berliners.

Berliners would eagerly await any positive news that might indicate the city’s relief – but to no avail.

Despite the remarkable calm and order in parts of its cities, Nazi Germany was in-fact flailing wildly in its dying throes.

In a futile attempt to limit the advance of the Soviet forces on the Oder on April 17th, a kamikaze squadron had been mobilised by the German Luftwaffe to attack the bridgeheads established across the river being used by the Soviets to reinforce their front. These Selbstopfereinsatz (Self-sacrificing missions) were being conducted from the town of Jüterbog by pilots of the Leonidas squadron. Thirty five pilots would die on April 17th for a limited and temporary success.

Early in the day – as this squadron plunged into bridges behind them – the troops of Marshal Georgy Zhukov’s 1st Belorussian Front remained stuck at the Seelow Heights, having advanced the previous day to the first line of fortified defenses – and struggled to push further.

Failure in the Red Army, of course, did not come without consequence, beyond the losses on the battlefield – as over the duration of the war over 230 generals and admirals would be shot or drafted into penal battalions for failure to deliver the right results. Under these circumstances, the lives of every day soldiers became more expendable – if progress demanded it, the road to success would be paved over their corpses.

Before the start of the battle, the Communist Party of the Soviet Union had seen an increase in membership applications from the soldiers of the Red Army readying to fight outside Berlin on the Oder and Neisse rivers. As unlike the British and American forces, the Red Army had no dog tag system of identification and thus no way of identifying corpses to inform families. If a Communist party member became a casualty though, the party would take care to notify next of kin.

Penal units of prisoners granted reprieve from their Siberian exile would be the most expendable. Although the Soviet Shock Armies that would be used to break through enemy defenses were often ordered to undertake nightmarish frontal assaults and batter at an enemy until gaps could be exploited by the more elite units.

Marshal Zhukov’s inability to move beyond the first line of German defenses on April 16th – the first day of the Battle of Seelow Heights – had meant the early deployment of his reserve forces and Tank Guards to try to speed up the advance. After the theatrical start to his attack, the Soviet Marshal would resort to a tried and tested method.

What could not be achieved through tactical éclat Zhukov would attempt to achieve through brute force – by bludgeoning the Nazi defenders with the overwhelming numerical supremacy of his Front.

Progress on April 17th, however, would be equally as limited, as the soldiers of the Zhukov’s 1st Belorussian Front struggled through minefields and across the flooded plain to reach the second line of German defenses – much more heavily manned than the first – but in few cases could push any further. One of the few exceptions coming when Vasiliy Chuikov’s 8th Guards, formed after the Battle of Stalingrad, managed to reach the Seelow Heights by noon on April 17th.

The mighty mechanised units of the Red Army, deployed to aid the attack, would be stuck churning mud. While anti-aircraft guns, manned by the German defenders blasted the Soviet troops at close range. Thinning the ranks and leaving burning wreckage to further hinder the advance.

Word from the field had reached Colonel General Mikhail Katukov, commander of the First Guards Tank Army, with the lead officer of his 65th Brigade stating: “We are standing on the heels of the infantry. We are stuck on our noses!”

In the weeks before the battle, the soldiers of the Red Army based along the front had been preparing themselves for the bloody offensive to come – but few, certainly not Zhukov, would have predicted how hard fought the initial stage of the battle would be.

And how determined German resistance would remain.

Konstantin Rokkosovsky’s 2nd Belorussian Front to the north of Zhukov would remain in their positions on April 17th – leaving Ivan Konev’s 1st Ukrainian Front further south of the main thrust as the flanking force looking to capitalise on the gains that they had made the previous day.

Unlike Zhukov, Konev was having much better luck in his sector.

It looked like the comradely competition between the two Marshals was entering a new stage. One which may see Konev reach Berlin before the man Stalin had chosen personally to lead the charge.

Marshal Ivan Konev’s resolve was evident in his orders of April 17th – the result of an earlier radio-telephone report to Joseph Stalin. The combined troops of the 1st Ukrainian Front, led by the 3rd Guards Tank Army and the 4th Guards Tank Army, were to take advantage of the delay to the advance further north.

The new target would be Berlin.

“Berlin for us was the object of such ardent desire,” Konev would later say. “That everyone, from soldier to general, wanted to see Berlin with their own eyes, to capture it by force of arms. This too was my ardent desire… I was overflowing with it.”

While Zhukov’s forces slugged it out with the Theodor Busse’s 9th Army, Konev had breached the line further south and had now been given the permission to exploit the gap.

“The tanks will advance daringly and resolutely in the main direction,” his orders would state. “They will bypass towns and large communities and not engage in protracted frontal fighting. I demand a firm understanding that the success of the tank armies depends on the boldness of the manoeuvre and the swiftness of the operation.”

The initial push would be towards the towns of Cottbus and Spremburg – with the Konev’s Tank Armies hitting the third defensive line there on the Upper Spree hard – to make a right turn towards Potsdam and threaten Berlin. His troops would discover an unmarked ford by which his two tank armies could speed up their advance and avoid engaging the two fortress towns, offering as they did the only bridges capable of taking heavy armour. Crossing the Spree virtually intact, they would thrust northwards – head for the road leading from Zossen to Berlin – ‘Der Weg zur Ewigkeit’ as it had been dubbed by German Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt (“The road to eternity”).

Throughout the first two days of the Soviet offensive on the Oder-Neisse line, Berliners on the outskirts of the city would register their concern at the sound of the distant guns – and changing atmospheric pressure. Yet, even with the city in sounding distance of the Soviet advance, the vast majority of the city’s industrial concerns were still producing. Gun barrels and mounts rolling off the line at the Rheinmetall-Borsig factory in Tegel, tanks and self propelled guns from Alkett in Ruhleben, and electrical equipment from the Siemens plant in Siemensstadt. All urgently making its way to the front – only 80km away.

Streets were crowded. Movie theatres were full. And at a cinema near Potsdamer Platz, reserved for German soldiers, the historical full-colour epic Kolberg (dealing with the heroic defence of the Pomeranian city during the Napoleonic Wars) was playing on special orders of Propaganda Minister, Joseph Goebbels.

By nightfall, Zhukov’s 5th Shock Army and 2nd Guards Tank Army finally pushed through the second line of German defenses on the Seelow Heights, codenamed Hardenberg – with one final line (Wotan) to break through. The 47th and 3rd Shock Armies, along with the 1st Guards Tank Army had also advanced – although the distances would still be measured in single digits.

As had been happening not so infrequently since 1940 – the British arrived in Berlin on the evening of April 17th. Disrupting life and forcing many of the city’s inhabitants to flee to air raid shelters and hide in cellar spaces.

Little evidence remains of the raid or its effectiveness – except that it was executed in a manner typical of the time, with a fleet of Royal Air Force De Havilland Mosquitos taking off to head to the Nazi capital late in the evening and returning to base early on the 18th. Sixty-one of these fast flying bombers would take part in the nocturnal attack.

Two would not return.

**

Our Related Tours

Want to learn more about the Battle of Berlin? Check out our Battle of Berlin tours to explore what remains of this important urban battlefield.

To learn more about the history of Nazi Germany and life in Hitler’s Third Reich, have a look at our Capital Of Tyranny tours.

Bibliography

Beevor, Antony (2003) Berlin: The Downfall 1945 | ISBN 978-0-14-028696-0

Hamilton, Aaron Stephan (2020) Bloody Streets: The Soviet Assault On Berlin | ISBN-13 : 978-1912866137

Kershaw, Ian (2001) Hitler, 1936–1945: Nemesis | ISBN 0-393-04994-9

Le Tissier, Tony (2010) Race for the Reichstag: the 1945 Battle for Berlin | ISBN: 978-1848842304

Le Tissier, Tony(2019) SS Charlemagne: The 33rd Waffen-Grenadier Division of the SS | ISBN: 978-1526756640

Mayo, Jonathan (2016) Hitler’s Last Day: Minute by Minute | ISBN: 978-1780722337

McCormack, David (2017) The Berlin 1945 Battlefield Guide Part I the Battle of the Oder-Neisse | ISBN: 978-1781556078

McCormack, David (2019) The Berlin 1945 Battlefield Guide Part II The Battle of Berlin | ISBN: 978-1781557396

Moorhouse, Roger (2010) Berlin at War | ISBN: 978-0465028559

Ryan, Cornelius (1966) The Last Battle | ISBN 978-0-671-40640-0

Sandner, Harald (2019) Hitler – Das Itinerar, Band IV (Taschenbuch): Aufenthaltsorte und Reisen von 1889 bis 1945 – Band IV: 1940 bis 1945 | ISBN: 978-3957231581

Shirer, William L. The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich | ISBN 978-1451651683.