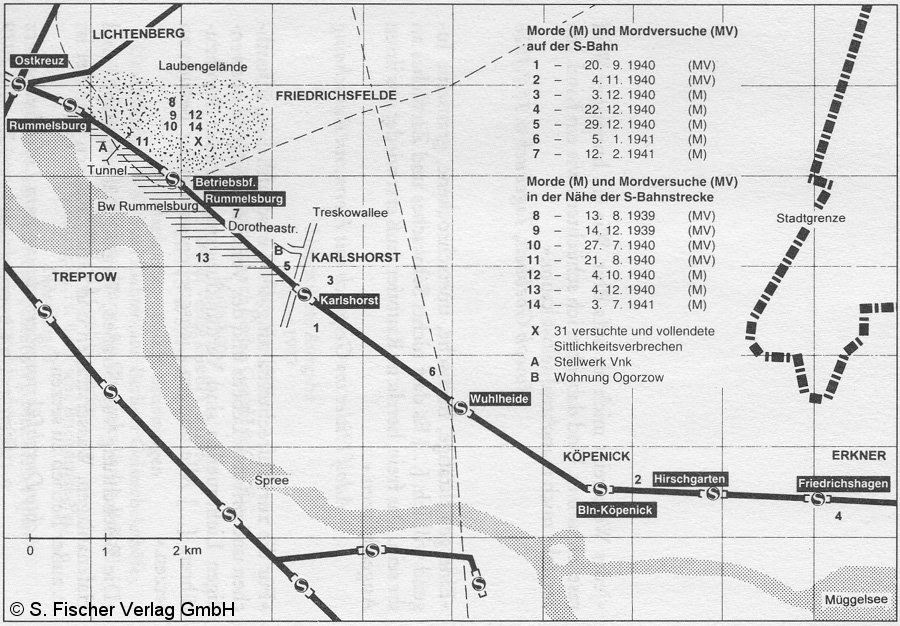

In August 1939, women in and around the district of Friedrichsfelde – an area of Berlin on the eastern edge of the city between the Rummelsburg and Karlshorst train stations – began to report of being harassed, randomly attacked, and sexually assaulted while out walking alone.

Although the Berlin police had not yet managed to connect the dots, these attacks – increasing in frequency and severity – were being carried out by one man.

One detail, reported by each of the women, matched in all cases: the attacker was dressed in the uniform of a railway worker.

Many of the women preyed on were solitary housewives whose husbands had been called up for military service. Targeted in the garden allotments of the area or the passageways between buildings; choked, bludgeoned, or stabbed, before being raped and left close to death. The threat of Allied air attacks on the Nazi capital at the time presenting the ideal window of opportunity for the attacker. Particularly after citywide blackouts were introduced – allowing him to hunt his victims in complete darkness at night.

A pattern was forming; but just as soon as the police began to piece together the parts of the puzzle, the attacks seemed to stop.

What they did not know was that their serial attacker had made a near-fatal mistake; caught in the act of assaulting a woman he had been beaten almost to death by her husband and brother-in-law.

As a result, he would add a new dimension to his crimes – lurking instead aboard empty train carriages and waiting for lone female passengers to board before strangling or striking his victims in the head with a 2-inch-thick piece of lead-encased telephone cable. Disposing of the bodies by throwing them from the carriage and onto the tracks. The inner city train network – the S-Bahn – serving as his new hunting ground.

Over the space of two years, the Berlin police would document thiry-one separate cases of rape and sexual assault carried out – with eight women killed – by the man who would become known as the ‘S-Bahn Murderer’.

With the efforts to apprehend the perpetrator hampered by the Nazi Propaganda Ministry’s refusal to allow details of the attacks to be published, a massive manhunt would be secretly undertaken, employing a slew of unusual methods in a desperate attempt to catch the killer before he could strike again.

Police officers would lurk in the shadows of the Berlin train network disguised as lone female passengers; and a citywide chaperone system where men could volunteer to accompany women on the S-Bahn and see them safely to their homes would be introducted.

To Nazi Party officials, these heinous crimes could only be the work of a foreign labourer – or local Jews.

No ‘racially pure’ German could possibly be responsible for such outrageous cruelty.

Be that as it may, the man they were looking for would turn out to be a model German citizen – a veteran Nazi Party member – even volunteering for escort duty. Seeing all his charges safely home and protecting them vigilantly from himself.

–

The Man Of Many Uniforms

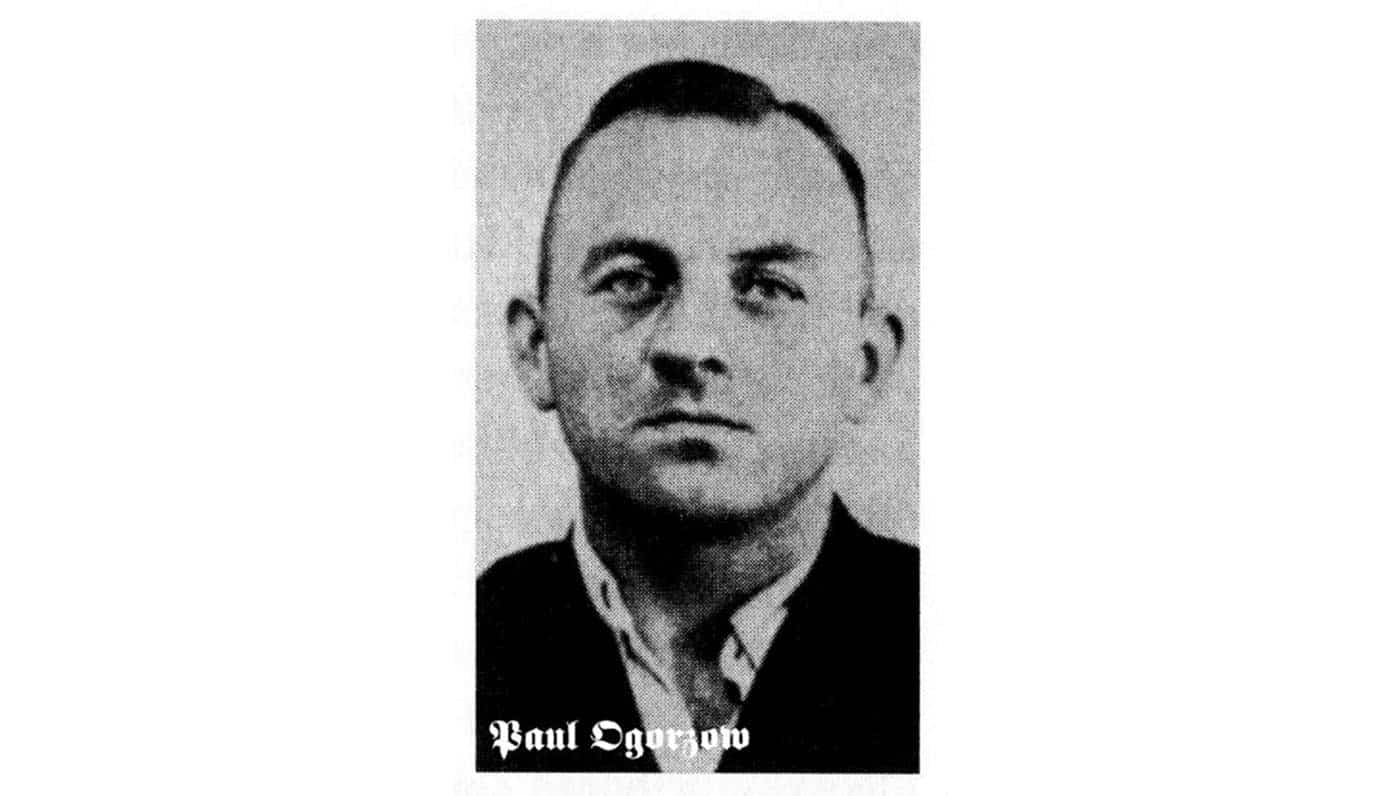

Born in September 1912, in the village of Muntowen, East Prussia (then part of the German Empire), Paul Ogorzow was the illegitimate child of a farm labourer who never knew the identity of his biological father. Adopted at the age of 12, he moved to the Havelland area, near Berlin, and worked as a laborer on his adoptive father’s farm before taking a job at a blast furnace in the Brandenburg steelworks.

In 1931, he joined the Nazi Party – two years before Hitler seized power – and the following year became a member of its paramilitary branch, the Sturmabteilung (SA). In 1934, Ogorzow joined the Deutsches Reichsbahn, the German national rail company responsible for running Berlin’s S-Bahn network, as a platelayer – overseeing the maintenance and installation of rails. Working his way up the organisation, he eventually attained the position of assistant signalman in a freight yard, located in the Berlin district of Rummelsburg.

Following his marriage in 1937 to a woman named Gertrude Ziegelmann, a saleswoman two years older than himself, he moved to the district of Karlshorst – near where most of his crimes later occured. Regarded by his co-workers as competent and trustworthy, he would travel to work daily by train, or sometimes by bike – always wearing his uniform.

Through his work he would become familiar with the rail network across the city; learning that lone female passengers were often not suspicious of a uniformed railway employee approaching them, apparently to ask for their ticket. When not working, he was often seen at home playing with his two children – a son and daughter – tending a vegetable patch in front of his apartment or picking cherries from a tree in the back garden.

Later, when his killing spree was well underway, his neighbour – a master butcher – hangs a post in his window warning of the serial murderer on the loose.

Ogorzow notices and talks to him.

“He could live next door!” say the butcher.

–

Death Rides The Rails

During his early attacks, Ogorzow had unsuccessfully attempted to murder his victims.

In-fact, three women whom he targeted and stabbed in the arbor grounds between Rummelsburg, Friedrichsfelde and Karlshorst would recover and later testify against him.

In August 1940, he bludgeoned and raped a woman, who only narrowly managed to survive after Ogorzow mistakenly thought she had died after she lost consciousness.

Another victim the next month survived being strangled and thrown from a moving train – the first attack carried out by Ogorzow in what would become his trademark hunting ground.

On the evening of September 20th 1940, Gerda Kargoll was on her way home – tired from a long day, she fell asleep on the train and woke up past her station. Worried that her ticket only covered her initial journey she boarded a train in the opposite direction knowing that if she were stopped by a ticket inspector she would have to pay a fine for riding farther than she should have.

The Berlin train network in 1940 offered two classes of available transportation – third and second class – Kargoll had bought a third class ticket for the cost of 20 Reichspfennig. First class travel was only for long-distance trains and the fourth class, that was introduced to make travelling for the poor more affordable, had been abolished in 1928.

It would later be established that Ogorzow would attack his victims in the second class compartments of the S-bahn, as there were drastically fewer passengers.

Spotting Gerda Kargoll in a third class carriage, Ogorzow approached the visibly distressed woman and finding that her ticket was not valid for the journey he offered that she could ride with him – in the second class area of the train. A free upgrade. As a worker of the Reichsbahn, Ogorzow had a pass to use the train and wearing his uniform he no doubt seemed a reassuring presence in the empty carriage.

Just after 11.30pm, as the train was en-route to Karlshorst station, Ogorzow moved towards Kargoll and wrapped his hands around her neck, intending to quickly knock her unconscious, rape and then kill her.

The attempt to subdue his victim, however, would take longer than Ogorzow had hoped, as Kargoll fought against him and tried to move towards the door of the train. There was not much time between stations and Ogorzow, familiar with the route and the time constraints, knew he only had between three and five minutes to carry out any attack.

With the woman he had just attacked now unconscious, the would-be killer panicked. Wanting to get rid of what he thought was a dead body, he opened the carriage door and threw Gerda Kargoll from the train, tossing her belongings – including her purse – immediately after. He could live with himself as a sexual predator, but Ogorzow did not steal.

The forensic pathologist, and psychiatrist, who would later come to work on the case – Dr. Waldemar Weimann – would pinpoint this moment as being the turning point in Ogorzow’s attacks. Previously he had attempted to murder his victims to cover his tracks, this time, throwing Gerda Kargoll’s seemingly lifeless body into the darkness, Ogorzow discovered he enjoyed killing women.

The sexual aspect of his crimes would continue but his future victims would be targeted for murder.

Gerda Kargoll likely survived due to an amazing stroke of good luck; landing on a soft pile of sand by the side of the track, as the train was travelling at around 80km per hour. Interviewed by the police, Kargoll claimed she understandably remembered nothing between being strangled and waking up beside the track.

As she had not been sexually assaulted and her belongings were found nearby; the police concluded that her story was a hoax or drunken accident.

Bodies would often turn up near train stations in 1940 – during one month alone, in December, there were twenty-eight people who died from blackout related incidents on the train tracks in Berlin. Automobile accidents were also a frequent occurrence due to the dimmed headlights on cars and the lack of streetlights.

The police did not yet suspect it; but the attack on Gerda Kargoll would be the first carried out on Berlin’s train network by the man who would come to be known as the ‘S-Bahn Murderer’.

–

A Murder Close To Home

For his first murder, Ogorzow returned to his old stomping ground in the garden colony area of the district of Friedrichsfelde.

At the start of October 1940, he had met a woman named Gertrude Ditter – a twenty-year-old mother of two whose husband, Arthur Ditter, was away in the military – at the Rummelsburg station.

She had invited him to visit her and provided an address – Kolonie Gutland II, path 5a, number 33.

On October 3rd 1940, Ogorzow called on Ditter during a blackout, and with her two young children sleeping in the living room, the two sat talking in the kitchen of the apartment. After enough small talk for Ditter to lower her guard, Ogorzow lunged at his victim and – grabbing her throat – squeezed hard enough to break her hyoid bone. A broken hyoid bone in cases where only skeletal remains are found is a strong indicator of strangulation. In Ditter’s case though it was not the strangulation that killed her. Despite the broken hyoid bone, she was still alive – until Ogorzow severed her left carotid artery with a knife he was carrying. She quickly bled out.

Gertrude Ditter was discovered the following day, when a worker from the National Socialist People’s Welfare organisation (the NSV) called on her and discovered the front door unlocked. The state was in the process of taking custody of her two children as she became Paul Ogorzow’s first murder victim.

The timing of the attack meant that the first assumption was that Ditter had actually committed suicide – a crime handled by the Order Police (Ordnungspolizei – commonly referred to as the Orpo), mostly uniformed police tasked with dealing with relatively low-level police matters. Alhough the police on the scene, concluding that people do not normally commit suicide by strangling and stabbing themselves, decided to refer the matter to the Berlin Criminal Police (better known as the Kripo).

The lack of defensive wounds would suggest that the victim knew her killer and within hours of Ditter’s body being discovered, the her husband Arthur – who was stationed in nearby Potsdam – had been located and interviewed. The distraught Mr Ditter provided a detailed five page statement explaining his whereabouts over the previous 48 hours and his cordial relationship with his wife. He was stationed only thirty minutes from Berlin but was not free to come and go from his barracks, leading the police to rule him out as a potential suspect.

By strange coincidence, Arthur Ditter had previously been employed at the Rummelsburg train-switching yard – ground zero for the S-bahn murders – where Paul Ogorzow worked as an auxiliary signalman.

At this point in time, however, the police had no idea who Ogorzow was.

The investigation would quickly turn into a cold case – with no fingerprints, no murder weapon, and few further leads – Gertrude Ditter’s killer was free to strike again.

–

Another Attack - An Important Clue

Exactly one month after his first murder, Ogorzow renewed his attacks on women travelling alone on Berlin’s S-Bahn network – focusing primarily on the 9 kilometer stretch between the Rummelsburg train yard and station and Friedrichshagen station.

On December 4th 1940, he attacked thirty-year-old Elizabeth Bendorf – a train ticket saleswoman who had just finished her shift at Friedrichshagen station. Although, as with his previous attack against Gerda Kargoll, Ogorzow did not manage to murder his victim. Despite repeatedly bludgeoning Bendorf with a thick piece of lead cable, the young woman survived.

Twice she regained consciousness before Ogorzow viciously attacked her again each time.

Miraculously although too dazed to move her body Bendorf would cognizant enough to recall being dragged to the door of the carriage. Again, frustrated by the time it had taken to subdue his victim, Ogorzow decided to throw Bendorf from the moving train – shortly before it arrived at the Köpenick station.

Like Gerda Kargoll, Elizabeth Bendorf survived a brutal attack. Her description of the incident meant that the first case no longer looked like the drunken accident that the police had suspected. A pattern was beginning to appear, of a man attacking women on the Berlin train network and throwing their unconscious bodies onto the tracks. Accidents were handled by the Ordnungspolizei, attempted murders – of which there were now two with similar details – was a matter for the Criminal Police.

Unlike with the murder of Gertrude Ditter, after his latest attack Ogorzow had decided to abandon his weapon. Hiding it behind the cushions of the second class carriage. The police investigation would manage to identify the train and carriage – leading to the discovery of an important clue:

A two-inch-thick, twenty-inch-long piece of lead encased telephone cable with numbers stamped on one side.

When the police contacted the telephone company they discovered that about a year and half ago, telephone cable had been laid alongside parts of the S-Bahn track. The number on the piece indicated it had been spliced off somewhere near the Rummelsburg S-Bahn station.

The police were one step closer to catching Ogorzow.

But another seven women would die by his hand before the hunt would come to an end.

–

Blood On The Tracks

Paul Ogorzow had by now tried twice – and failed – to murder his victims on the S-Bahn.

Constrained by the timetable of the network, he had little time to subdue and kill the women he attacked and then dispose of their bodies. Unlike with his attack on Gertrude Ditter, in the privacy of her own home, where he had ample opportunity to savour his handiwork and confirm that she was actually dead, he was struggling to satiate his lust for murder on the rails.

His next outburst would see him butcher two women within hours of each other.

Ogorzow’s attacks were also now taking on a strange pattern, one the police were unable yet to detect.

Exactly one month after murdering Ditter, he had attacked Elizabeth Bendorf, and exactly one month later – on December 4th, he would strike again.

This time, carrying an iron rod he had found during his work at the railway yard, he would shatter the skull of a twenty-six-year-old nurse named Elfriede Franke.

Spotting Franke in the second class train compartment at the Karlshorst station, Ogorzow wasted no time – or words – and, removing the iron rod from his jacket, slammed it hard into Franke’s head, forcing pieces of her skull into her brain.

She immediately fell down onto the floor of the carriage.

Satisfied that he had succeeded where he had earlier failed – and that the young nurse was indeed dead – Ogorzow moved to open the door of the carriage, allowing the cold air of the winter night to rush into the compartment.

Then, dragging Franke by her feet, he threw her body into the darkness.

Three hours later, with the citywide blackout still in effect, the police arrived at the body; joined by the well-known forensic pathologist Waldemar Weimann. The officers at the scene were quick to note that this was the third case of this kind that they had encountered along this route – Weimann was asked to make an assessment. Two other women had both survived, one had been strangled while the other had been hit with a blunt instrument. The detail that connected all three – other than the location – was that they had each been thrown from a moving train. Could these cases all be the work of the same man? Weimann was unsure.

What neither the police nor Weimann were aware of at the time was that the doctor had also examined one of Ogorzow’s other victims. Gertrude Ditter, who had been strangled and stabbed in her garden home in Friedrichsfelde.

The connection between these crimes had not yet been made. But the police were beginning to suspect that they were searching for one individual, responsible for two previous attacks and now the murder of Elizabeth Bendorf.

With violent crimes grouped together when the attacks are carried out in a similar way, Ogorzow’s earlier spree in the garden colonies and side-streets of Friedrichsfelde where he stabbed and strangled his victims before sexually assaulting them had, however, still not been tied to the incidents on the S-Bahn network.

The modus operandi and locations were too different.

As the brutality of Ogorzow’s crimes increased, the Nazi Party responded with a media blackout that only served to stymie the investigation, allowing the S-Bahn Murderer to secure his moniker.

But the man in charge of the pursuit of Ogorzow was not to be deterred.

–

The Hunt For The S-Bahn Murderer

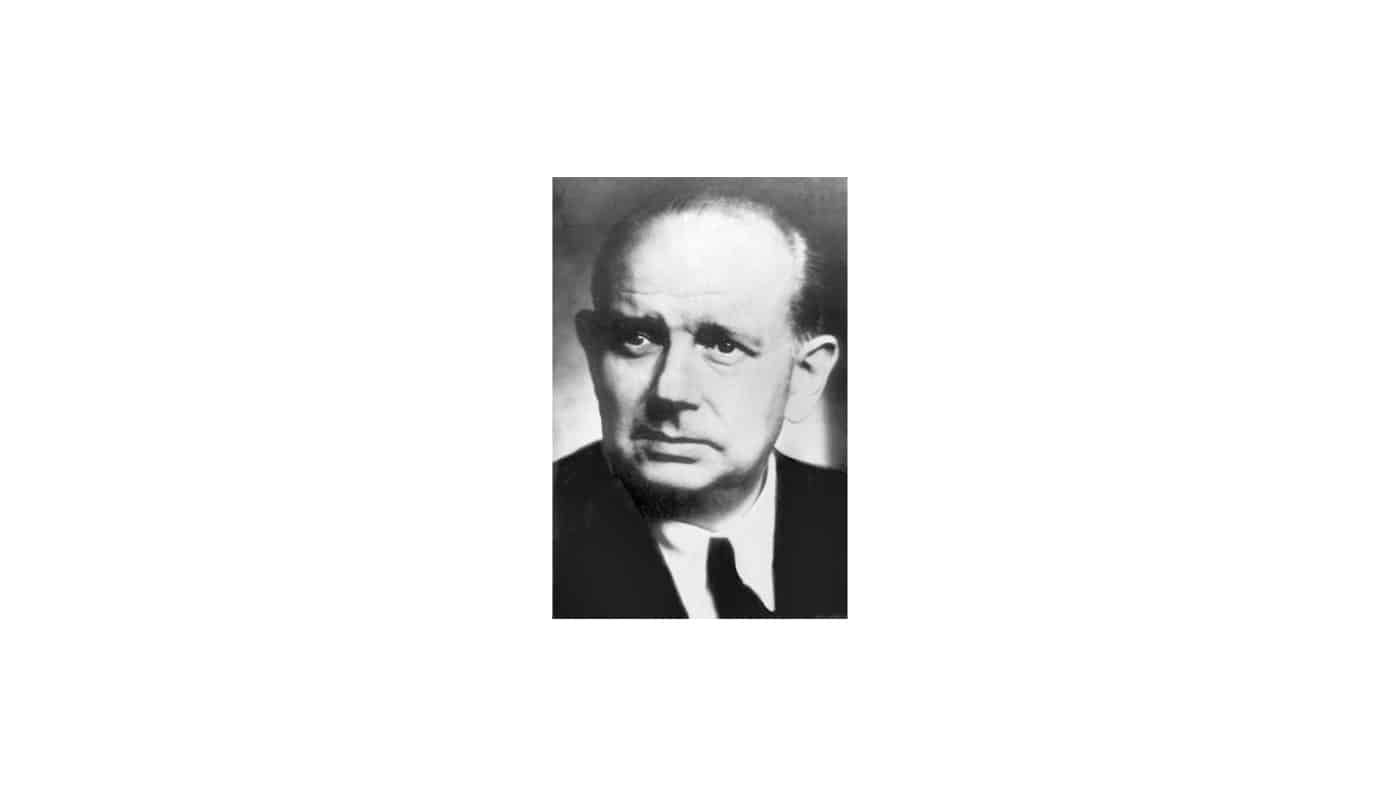

The day that Elfriede Franke was murdered, the police operation against Ogorzow was taken over personally by the head of the Serious Crimes Unit of Berlin’s Criminal Police force (better known as the Kripo), Wilhelm Lüdtke – a veteran police officer, who first joined the Schutzpolizei in 1910.

Since the Nazi seizure of power in 1933, the Kripo had come to serve as a revolving door to Party membership – as the distinction between ‘ordinary’ crimes and political crimes blurred so that there was no clear division of labor between the criminal and political police. As of September 1939, the Kripo was part of the Reich Main Security Office, headed by Heinrich Himmler. As such, the Gestapo (Nazi Secret Police) and the Kripo often found themselves sharing jurisdictional authority with regard to certain criminal violations – and in 1940, Lüdtke would finally join the Nazi Party, taking the rank of Hauptsturmfuhrer (Captain) in the SS.

Without knowing it Lüdtke joined the Nazi Party exactly eight years to the day after Paul Ogorzow had – as member 8,015,159.

Like plenty of his fellow officers, Lüdtke had not supported the Nazi Party during its rise to power. In-fact, like Berhard Weiss – the Vice-President of the Berlin police, who had been forced out of his job due to his Jewish ancestry – the head of the Berlin Serious Crimes Unit had been a member of the liberal Deutsche Demokratische Partei. Dismissively referred to by the Nazis as the “party of Jews and professors”, the DDP was co-founded by Albert Einstein and included people such as economist Walter Rathenau, sociologist Max Weber, and author of the Weimar constitution Hugo Preuss, among its members.

His post-war interrogation report, as part of the DeNazification of Germany, would describe Lüdtke as: “well-grounded in all phases of police investigative work but lacking the ingenuity and imagination required of an independent intelligence operator.” He would be involved in anti-smuggling operations aimed at stopping the illegal flow of coffee into East Germany but not offered a position with the CIA.

Luckily for Lüdtke, denunciations were the bread-and-butter of most Nazi-era investigations – and as such the final piece of the puzzle would fall into place when the police received a tip-off from one of Ogorzow’s co-workers about his unusual behaviour.

Despite the elaborate measures introduced by the Berlin police to help apprehend Ogorzow, and a hefty ransom offered, little progress had been made, although they had managed to catch more than a handful of petty criminals unrelated to the case.

Following the murder of Elfriede Franke on December 4th 1940, Paul Ogorzow would be on the loose for another eight months before his capture in July 1941.

The police would later describe him of limited intelligence; although he appeared to be outwitting them at every turn.

–

A Serial Killer On The Loose

While the Berlin police were gathered around the body of Elfriede Franke on December 4th 1940, only a few kilometers away Ogorzow attacked and murdered his third victim – not long after arriving at the Karlshorst station.

Having swiftly dispatched Franke with a blow to the head, Ogorzow found that he still had a burning desire to sexually assault a woman.

Using the same iron rod that he had employed to kill Franke, he knocked out a nineteen-year-old named Irmgard Freese that he had spotted walking alone. After crushing her skull with three blows, Ogorzow ripped off much of her clothing and raped her. Leaving her for dead as he returned to the S-Bahn signal station where he worked to rest. An isolated building on the outskirts of the station, he would often fall asleep here instead of going home.

It was only thirty minutes after his attack on Elfriede Franke.

Discovered by people walking in the area, Freese was rushed to hospital while still alive. She would die without being able to speak a word about the attack.

After the autopsy of Irmgard Freese was conducted and the cause of death identified as being similar to previous attacks, the two men largely responsible in the hunt for Ogorzow would soon come to realise they were looking for one man responsible for an series of escalating attacks.

Kriminalkommissar Wilhelm Lüdtke and Doctor Waldemar Weimann met the day after the murder of Freese at Weimann’s home. Lüdtke presented the doctor with a detailed map of the garden area where Ogorzow had been harassing and sexually assaulting women, suggesting the possibility that they could be tied to the S-bahn attacks and introducing one key connection – the murder of Gertrude Ditter in her garden house.

Could it not be possible that the crimes had been committed by the same man, taking into account the distribution of the attacks, the origin of the telephone cable used to bludgeon Elizabeth Bendorf?

More significantly, Lüdtke would propose:

Why is it that since the first woman was thrown from the S-bahn that the police have not heard of any more attacks in the garden area?

Lüdtke was correct in his assumption.

By this time Ogorzow had changed territory. Of the two areas he was familiar with, the garden colony in Friedrichsfelde and the S-Bahn lines, he was now focusing almost entirely on the latter.

Before the end of the month he struck again; killing a thirty-year-old woman named Elisabeth Büngener who had been riding the S-Bahn to see her husband, a soldier in a town near Berlin called Fürstenwalde, a few days before Christmas. Beaten with a blunt object, Büngener was thrown from the train whilst still alive but died from injuries sustained when she hit the ground. At first the police thought this was a suicide, as a doctor’s note was on her person declaring her unfit for work – and such events were common so close to Christmas. But a detailed examination of the body would reveal telltale signs that her death had been the work of the S-Bahn Murderer.

The death of Elisabeth Büngener was added to Paul Ogorzow’s tally – which now stood at four murdered women and countless other harassed and sexually assaulted.

In the early hour of December 29th 1940, Ogorzow found a forty-year-old woman named Gertrud Siewert travelling in the second class compartment of the Berlin S-Bahn line between Karlshorst and Rummelsburg. With a single blow to the head, Siewert was incapacitated and thrown from the train. She was still alive when discovered later that morning and rushed to hospital but died the same day.

On January 4th 1941, a twenty-seven-year old mother-to-be named Hedwig Ebauer was discovered, still alive, by the side of the train tracks near the Wuhlheide S-Bahn station. Although she arrived at the hospital alive, she died there the same day, as a result of head injuries sustained when she fell from a moving train. Prior to landing beside the track she had been strangled by Paul Ogorzow, who – having mistakenly thought she was dead – threw her from the carriage like his previous victims.

This was Ogorzow’s third attack in the early hours of a Sunday morning and based on where Ebauer had been found the police were able to identify which train compartment she had likely been attacked in. What seemed like a promising lead turned out to be a dead end, when detectives entered the carriage and found it had been cleaned since the attack. All evidence swept away.

With four women now murdered while riding the city’s S-Bahn, rumours started to spread throughout Berlin that there was a serial killer riding the trains. The kind of publicity that Reich Propaganda Minister, Joseph Goebbels, was anxious to control. Certainly when it cast the regime in such a bad light – that the German police could not stop a serial killer from murdering women in the heart of the Reich.

Ogorzow was committing his crimes right under the noses of the Berlin police – continuing to terrorise the city despite one of the most unusual manhunts in the city’s history being mounted. He even came close to being caught whilst approaching a female passenger at night on a train before realising that she was an undercover female police officer – luckily for Ogorzow, the Berlin police had refused to arm their undercover female officers and he was able to jump from the moving train and get away.

In a strange way, the police hunt for the S-Bahn Murderer was even starting to help Ogorzow commit his crimes.

His next murder would occur on the night of February 11th 1941, when he was approached by a thirty-nine-year-old woman named Johanna Voigt at the Karlshorst station. Voigt was concerned about the rumours of the serial killer and asked Ogorzow if he would accompany her on the train – she was three months pregnant. Once the train arrived, they entered together – boarding the second class carriage. As Voigt was only riding to the next station, Ogorzow had to act quickly. Armed with the iron bar he had used in prior attacks, he struck Voigt in the head numerous times, rendering her unconscious. Like a number of his previous victims, Johanna Voigt was still alive when she was thrown from the moving train but would not survive the injuries sustained in the fall.

There were few additional clues on Johanna Voigt’s body to lead the police to the killer but on closer inspection one thing did occur to Kriminalkommissar Lüdtke. He realised that on a number of victims, the train ticket was missing, indicating that the offender may have been a ticket inspector – or railway worker.

The police presence at the Rummelsburg and Karlshorst train stations, where the previous attacks occurred, increased. Some news of the attacks managed to make it into the press – but on the whole, the Nazi Party did its best to reign in the story, even when the police were adamant that more publicity would help them catch their man.

The police were offering a substantial reward for information that would lead to the capture of the S-Bahn Murderer – by this time it was set at 13,000 Reichsmarks, and this did bring in around 15,000 tips. Far too many for the police to follow up.

Those women who did not know about the man preying on lone females on the city’s train network were still out there as potential victims – the few that managed to be scared away by the rumours and hushed announcements from the police meant that there would be fewer people riding the second-class compartments likely to disturb Ogorzow.

To kill, he only needed one victim, and it only worked if she was alone.

Ogorzow had been volunteering to escort women home, as part of the government scheme to stop them travelling alone at night, and never bothered any of them. Although, the murder of Johanna Voigt had taken place immediately after he had left one of his charges.

In February 1941, the police began questioning all the Reichsbahn employees – there were 5,000 of them – eliminating those who did not match the descriptions given by Ogorzow’s earlier victims who had survived.

With all the police activity, Ogorzow did stop his attacks, if only temporarily. Biding his time until the police started to scale down their operations.

Days turned into weeks.

Weeks turned into months.

–

A Deadly Gamble & A Red Herring

On July 1st 1941, Kriminalkommissar Lüdtke set a dangerous trap. He had his officers spread the rumour that from this day police monitoring would cease, “as it is obviously futile”.

The rumour reached Ogorzow and two days later he took the train to the Rummelsberg station where he stalked a group of nine women – choosing one who left the station alone. Her name was Frieda Koziol and she was thirty-five-years-old. Ogorzow was wearing his railway workers uniform and approached Koziol from behind, offering to walk her home, she refused and kept walking – at which point Ogorzow smashed her in the back of the head with his iron bar, caving in her skull.

As she lay dying, he raped her, leaving her body where it was – naked from the waist.

Desperate to solve this series of murders, Kriminalkommissar Lüdtke now had blood on his hands.

He would later justify his decision by pointing out that he had hoped to catch the perpetrator in the act. By now any doubt that remained that Ogorzow was behind the S-Bahn attacks and those that had taken place in the garden spaces of Friedrichsfelde had disappeared from Lüdtke’s mind. He also became certain that the killing of Gertrude Ditter, who Ogorzow had choked and stabbed in her own home, was also the work of the elusive railway worker.

Following the murder of Frieda Koziol, the police found a clear trail of shoeprints in the dirt nearby. Determined to be a men’s thirty-nine and a half, a specialised shoe with extra thick rubber soles, made by the company Salamander. War-time rationing meant that a list of men who had purchased this particular shoe could be drawn up and it looked like the police were one step closer to catching their killer.

Alas, it turned out to be a red herring.

After eliminating the men who were on military service or were too far from the crime scene, they found that a man named W. Heimann, who lived nearby, had bought a pair. And he had a criminal record – for spying on a couple having sex. Heimann was taken into custody and his shoes analysed – compared against molds of the shoe prints left at the scene.

They matched.

Heimann was held for three days and interrogated eight times before he confessed that he had been at the crime scene but fled when he noticed that the woman was dead. He insisted he was not the attacker.

Something else puzzled the police. He had no connection to the S-Bahn system, other than occasionally riding it.

Luckily for Heimann, the police decided against pinning the crimes on him. Knowing that judging by the type of crimes they were looking at that the perpetrator would likely continue his deadly work unless captured.

–

The Capture Of The S-Bahn Murderer

The police would receive their biggest break in July 1941 with the use of a single question.

The kind of question that would come to be extremely useful in Nazi Germany:

“Have you noticed anything suspicious about any of your coworkers?”

While interviewing a particular railway worker, who they had alredy cleared of being involved, the Kripo detectives asked this question and were given what may have seemed like a mundane reply. The worker had indeed seen something unusual, he had spotted one of his coworkers ditching his job by climbing the fence at the railway yard, only to return later before anyone else noticed.

The police had already talked to this other worker and discovered that some of the crimes had taken place during times when he was at work. This had seemed enough at the time to warrant clearing him of any involvement. Now they wanted to talk to him again.

On July 12th 1941, Paul Ogorow was picked up from his apartment at 6:45am by a Kripo detective and two low ranking officers. On being questioned by Kriminalkommissar Lüdtke he denied having temporarily abandoned his post, claiming that his duties meant that had he done so he would easily have been detected by his superiors.

On paper he looked like the exact opposite of what the police were looking for: a family man, a loyal Nazi, a veteran of the Sturmabteilung, and a dedicated worker, who was – aside from his nosy coworker – spoken highly of by his peers and superiors.

Eventually he retracted his statement about leaving his post and claimed he was visiting a woman with whom he was having an affair. When the woman he claimed to have been meeting was brought in for questioning, she admitted that the two had indeed been having an affair – one they intended to keep secret as her husband was away in the military.

Had that been the end of the story, Ogorzow may have been released. But on being taken in for questioning, the police had confiscated his clothes and sent them away to be checked for anything suspicious.

Microscopic analysis had uncovered blood on Ogorzow’s jacket and trousers. With a large amount found in and around the crotch area of the trousers.

Trying to explain away the evidence, Ogorzow claimed that his wife had been sick and that it was her blood on his clothing, adding that the rest must have come from when he cut his finger. Ogorzow’s wife would corroborate his story about her being sick – but the police were convinced that the bloodstain on his jacket was the result of a struggle.

Gradually, over a period of days, Ogorzow cracked.

First, confessing to stalking women in the garden areas of Friedrichsfelde, using a flashlight to scare someone or grabbing a woman walking alone. Ogorzow was then taken to trace the steps of his earlier minor crimes, accidentally letting slip that he had been involved in some more serious attacks in the process.

The police then brought two women who had survived Ogorzow’s attacks to identify him – one immediately recognised him, the other said she was not sure. Rather than organise a line-up of suspects, they had simply brought the women to the garden colony in Friedrichsfelde and had them stand in front of Ogorzow.

On the way back to the police station, Paul Ogorzow requested that he be allowed to talk to the man in charge of the case – Wilhelm Lüdtke – perhaps expecting that a high level official might help him out due to his Nazi credentials.

–

The End Of The S-Bahn Murderer

Already somewhat certain that he had his man and with the Nazi Party breathing down his neck to catch a criminal who had been terrorising the Nazi capital for nearly two years, Kiminalkommissar Wilhelm Lüdtke wanted a confession from Ogorzow.

He would go about getting it in a rather macabre way.

The skulls of five of Ogorzow’s victims were placed on the interrogation table in front of Ogorzow, carefully cleaned and presented by the forensic pathologist, Dr Weimann.

The young railway worker did not last long. Soon pleading with Lüdtke to find a way to make the criminal charges he was facing go away. The Kriminalkommissar’s response was to assure Ogorzow that he would be well treated, as long as he provided a full confession.

Tempted by this offer, Ogorzow related the details of his crimes, although stating that he had used a knife to murder his victims – a lie concocted to allow him to wriggle out of any proceedings against him, should he be unfairly treated by Lüdtke.

Carefully walking Ogorzow through the details of each murder, and using the skulls in front of him as props, Lüdtke exposed Ogorzow’s amateur subterfuge. Eventually, Ogorzow would have to admit that he had bludgeoned the woman, in his own words: “with a lead cable.”

In his confession, Paul Ogorzow blamed his acts on sexually transmitted diseases that he had caught three times – in Berlin in 1934, in Poland in 1940, and in Paris in 1940. His poor treatment by a Jewish doctor was also cited as something which affected his state of mind, making him not responsible for his actions.

Hoping his Party membership would save his life, he requested to be placed in a psychiatric hospital.

On July 18th 1941, the Berliner Morgenpost finally ran a front-page story about the S-Bahn Murderer. The headline read: “The Berlin S-Bahn Murderer Caught!”

Four days later, Ogorzow was put on trial at the Nazi Special Court for the murder of eight women and the attempted murder of a further six. The court ruled he was fully sane and responsible for his actions and he was convicted on all eight counts of premeditated murder and six counts of attempted murder.

The next morning at 6am, Paul Ogorzow – the infamous S-Bahn Murderer – was executed at the Plötzensee prison in Berlin by guillotine. As was usually the case with such executions, a charge for the wear and tear of the guillotine blade was sent to the prisoner’s relatives – in this case Mrs Gertrude Ogorzow.

–

Coda - A Killer In The Shadows

In a criminal state like Nazi Germany, where murder was state policy, it may seem somewhat fanciful that the kind of peace-time policing that involves catching thieves, rapists, and murderers, would continue as normal, when such colossal criminality and nefarious acts was being committed daily by the government – in the name of the people.

Certainly in the Germany of the 1930s and 40s, there was no shortage of men whose hands were wet with blood. Yet that the phenomenon of the serial killer – or civilian spree killer – which in the late 20th century became so closely associated with the United States – should also have occurred in Nazi Germany is still a surprise to many.

More than just a movement of ideas, Hitler’s National Socialist Party would prove to be a Party of deeds.

In implementing its platform and policies, the Party stood at odds with the status quo of political discourse. Whether deployed during the early street battles to establish the Party, to further the cause of German expansion or attain the Nazi goal of racial purity – violence was always an essential part of the National Socialist repertoire. And not necessarily a matter of last resort. Unlike other political movements where violence was perceived as temporary and transcendental – bloodshed was an integral part of the National Socialist doctrine, acceptable as long as it was administered appropriately.

As such, the legacy of Ogorzow’s deeds has largely been eclipsed by the greater criminality of the Holocaust, the Second World War, and the litany of other Nazi crimes.

Leaving the ‘S-bahn Murderer’ exactly where he chose to prey on his victims – in the shadows.

**

If you’ve enjoyed reading this article, consider booking one of our private guided tours of Berlin.

If you’re interested in reading more about the case of the S-bahn Murderer – check out the expertly researched and written A Serial Killer in Nazi Berlin by Scott Andrew Selby.

Our Related Tours

To learn more about the history of Nazi Germany and life in Hitler’s Third Reich, have a look at our Capital Of Tyranny tours.

Think you already know enough about the rise and fall of the Third Reich? Take our Capital Of Tyranny Quiz and find out.

Sources

Alt, Axel (1944). Death was on the train. Retold the files of the criminal police. Hermann Hillger publishing house, Berlin-Grunewald and Leipzig

Bosetzky, Horst (1995). Like an animal. The S-Bahn killer. Argon Verlag 1995 / Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, Munich 1997, ISBN 3-423-20021-9 .

Moorhouse, Roger (2010). Berlin at War: Life and Death in Hitler’s Capital. Bodley Head

Piethe, Marcel (2014). Paul Ogorzow – Der Berliner S-Bahnmörder

Selby, Scott Andrew (2014). A Serial Killer in Nazi Berlin: The Chilling True Story of the S-Bahn Murderer. Berkley Books, 2014, ISBN 978-0-425-26414-0.