German history is replete with kairotic moments: when opportunity and circumstance conspired to present the chance for revolutionary change.

Notably, the times when individuals have attempted to take destiny in their own hands – testing the divine right of Kings; and the dictator’s belief in providence. Attempting to eliminate key historical figures, by bullet; bomb; poison; or knife, and change the course of human history.

This is the story of four of those individuals and what might have been. Four attacks that took place on Berlin’s historic Unter den Linden – and almost succeeded.

Cutting through the heart of Berlin’s former royal district, Unter den Linden is the oldest boulevard in the city, connecting the reconstructed Berlin Palace to the Brandenburg Gate. Laid out in the 16th century as a bridle path to allow the local Elector, Johann Georg, to reach his hunting, the street would receive its namesake linden trees in the spring of 1647.

Over the next three centuries, the significance of Unter den Linden would increase as Berlin was expanded into a fortress then became the capital of the Kingdom of Prussia.

By the late 19th century, largely as a result of the intervention of master-architect Karl Friedrich Schinkel, Unter den Linden would be transformed into a complete ensemble – an expression of the grandeur and grandiose ambitions of the Prussia state – bringing together a near harmonious vision of the street while embracing various architectural styles. If, as is said, the first Roman emperor ‘found a city of brick and left it marble’, Schinkel found a city of wood and left it brick. Albeit swaddled in plaster and sandstone, and replete with statues and elaborate wrought iron.

Motorised transportation would arrive later; the first traffic police in Prussia; and electric street lighting, but to tourists and locals alike, Unter den Linden would remain first-and-foremost the city’s royal street.

More than just a royal capital, Berlin was also the capital of a mighty military power and visitors to the city would often remark on the conspicuous presence of men in uniform at almost every turn; the equestrian statue of Frederick the Great prominently displayed in the centre of Unter den Linden; the sculptures of the successful generals of the Napoleonic War – Blücher, Yorck, Gneisenau, Scharnhorst, and Bülow – marshalling their gaze on passersby.

As much as anyone taking a stroll on Unter den Linden was certain to be affected by the elegant neo-classical buildings in ‘Prussia style’, there was always the chance they could get caught up in a parade or catch a glimpse of the King in his open carriage.

The royal family felt safe here; and why should they not?

Right in the heart of one of the most formidable military powers in the world.

This grand boulevard, however, would become the site of a number of near-fatal encounters for some of the most significant figures in German history. Attracting a certain kind of individual; one intent on changing the course of history by the use of violence.

In less than a decade, there would be four assassination attempts carried out here, for various reasons, targeting three notable personalities in the story of Germany’s past – Otto von Bismarck; Emperor William I; and Nazi leader, Adolf Hitler.

The first of these attacks would take place in 1866, when the man who would come to be known as the ‘Iron Chancellor’ – Otto von Bismarck – would survive five shots from an assassin’s gun.

–

The Attempt On Otto von Bismarck

(May 6th 1866)

Following the unification of Germany in 1871, Otto von Bismarck would become a hero to German nationalists, who saw in him the man who had single-handedly masterminded the conditions necessary to bring about the long-overdue consolidation of the German states.

Bismarck had been instrumental in provoking three short wars – against Denmark, Austria, and France – the so-called ‘Wars of Unification’ and through “blood and iron” he and Prussian King Wilhelm I had managed to do what Wilhelm’s older brother, King Friedrich Wilhelm IV of Prussia, had failed to do less than a quarter of a century earlier. In 1849, the Prussian King had been offered the title of Emperor; urged to secure a German nation-state, with a pan-German constitution and a popular assembly by the first freely elected parliament for all of Germany.

That parliament had been established as a result of the popular uprising of 1848 and Friedrich Wilhelm IV would ultimately reject the crown, saying he could not accept what had been touched by “the hussy smell of revolution”. More than just his preference for the Divine Right of Kings, Friedrich Wilhelm was also worried about the disapproval of Austria – the hegemonic power in the German speaking world at that time.

Withdrawing from the public eye, the King suffered a series of strokes, starting on July 14th 1857 – leaving his incapacitated. His younger brother Wilhelm would soon take over the role of regent and finally succeed him in 1861 – acceding to the throne as Wilhelm I of Prussia.

The same year, the new King was attacked by a student named Oskar Becker, in the town of Baden Baden. Using two Terzerol muzzle-loading pistols, Becker shot at Wilhelm and grazed his neck – although the King claimed not to have noticed. The assassin-to-be was arrested and a letter of confession was found on his person. Becker had attacked Wilhelm because he believed that the King was incapable of dealing with the most pressing issue of the time – and that he must die in order for someone else to accomplish it.

The young student would be wrong about Wilhelm I, although he would not live long enough to know it. Sentenced to 20 years in prison for the attack, he actually received a pardon from the man he had tried to kill, in October 1866, but died two years later – largely forgotten.

The year of Becker’s release, Wilhelm I and the mighty Prussian Army had done something remarkable.

Wilhelm I had defeated Austria.

Clearing a major obstacle to German unification.

The politican who would help make this happen, Wilhelm I’s right hand man, was Otto von Bismarck.

A skilled practitioner of Realpolitik, the pragmatism-first approach to politics that by definition eschews ideological and idealistic pursuits, Bismarck would famously state that “Politics is the art of the possible.”

What looked possible in the 1860s was that Prussia, the German state with Berlin as its capital, would now come to dominate the German-speaking world and usher in a unified German state.

Back in 1862, Otto von Bismarck was made Minister President of Prussia and Foreign Minister by Wilhelm I and subsequently managed to reorient Prussia as the major military power in Europe. Working with two other dominant figures in the Prussian government during the key decade of the 1860s, Chief of the Prussian General Staff, Helmuth von Moltke, and Minister of War, Albrecht von Roon.

The first major step in addressing the balance of power in Europe was to ensure the Prussian Army was prepared for any future engagements that might happen. Bismarck would be integral in pushing against the liberal majority in parliament to grant money for the planned army reform.

A move that would earn him a reputation for hawkishness that would later come to haunt him but succeed in bolstering the might of the Prussian military.

The first major test of this newly reinvigorated power would come against Denmark.

In February 1864, Prussia allied with Austria over the question of the territories of Schleswig-Holstein, and fought an eight month war with Denmark. The casus belli being that the new Danish King had claimed control of the duchy of Schleswig, despite its German majority population, and that the German states were insistent that both Schleswig and Holstein not only remain joined together but should also become part of a future Germany.

The war ended on October 30th 1864, with Denmark’s cession of Schleswig, Holstein and Saxe-Lauenburg to be jointly administered by Prussia and Austria.

The Danish crown had lost 40% of its territory and the newly restructured Prussian Army had proven itself on the field of battle, contributing to a perception in the German states that Prussia was the only state that could defend the other German states against external aggression.

Bismarck’s popularity increased – as did that of Wilhelm I – but the alliance made with Austria would not survive for long following the end of the war.

In March 1866, Austrian troops were sent to reinforce its frontier with Prussia. Mobilisation of some Prussian forces followed later in the month and at the start of April, Otto von Bismarck made an alliance with Italy that stipulated that if a war broke out with Austria in the next three months that Italy would join and fight alongside Prussia.

Italian mobilisation took place shortly afterwards, and Austria – fearing attack – mobilised its entire army.

In response, the Prussia Army received general mobilisation orders at the start of May.

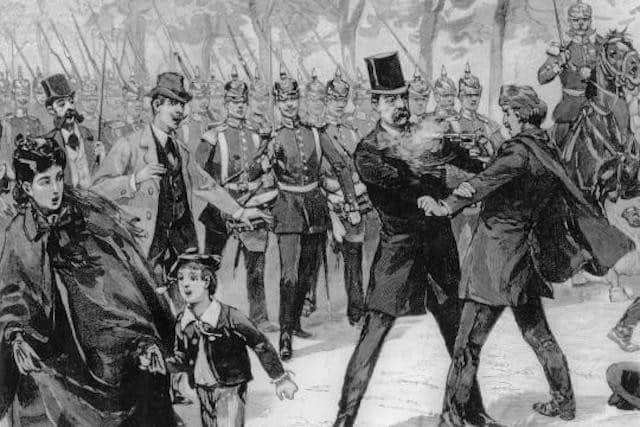

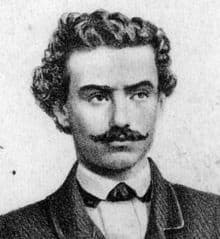

On May 7th 1866, Otto von Bismarck was confronted on Berlin’s Unter den Linden by a 22-year-old student named Ferdinand Cohen-Blind, who attempted to murder the Minister President and halt the path to war that the Prussian state was now set on.

Cohen-Blind had arrived in Berlin on May 5th and checked into the Hotel Royal on Unter den Linden, already intent on assassinating Bismarck. The assassin-to-be had cut short a holiday he was taking on hearing of the impending war and headed straight to the Prussian capital.

His opportunity came two days later, when he spotted the First Minister returning home on foot along Unter den Linden after meeting King Wilhelm I at the Berlin Palace.

Cohen-Blind approached Bismarck from behind and, without waiting for him to turn around, fired twice with a revolver.

Hearing the sound of the gun, Bismarck turned and grabbed the young student, who then fired three more shots.

Luckily for Bismarck, soldiers of the 1st Battalion of the 2nd Guards Regiment were at that moment marching past and rushed to arrest Cohen-Blind.

Rather than seek medical attention, the Prussian Minister President decided to continue home, greeting his wife with a few unrelated jokes he then headed into his study, returning to regale Johanna von Bismarck with the story of what had just happened.

Later that evening, Bismarck was examined by the King’s personal physician, Gustav von Lauer, who found that the first three bullets had only grazed his body while the last two bullets had actually ricocheted off his ribs; although causing no significant injuries.

Taken to the Berlin police headquarters to be interrogated, Ferdinand Cohen-Blind managed to sever his carotid artery using a knife and died on May 8th at 4am.

As it turns out, Cohen-Blind was not the only person to object to the imminent ‘fraternal war’ about to take place and Bismarck’s exercise in Realpolitik.

It was not uncommon for the First Minister to be spat on in the street by his compatriots but this was the first time that an attempt on his life had been made.

The previous month, Tsar Alexander II of Russia had survived a similar attack when he was fired on by Dmitry Karakozov – the first Russian Empire revolutionary to make an attempt on the life of a tsar.

Armed with pistols, bombs, and knives, would-be assassins were coming closer to those in power in the late 1800s and Alexander II would finally fall victim to an assassination in 1881 – dying in Saint Petersburg after being targeted with a bomb by the socialist revolutionary Narodnaya Volya (People’s Will) movement.

Three years before the Tsar’s death, it would be the turn of German Emperor William I – who survived two assassination attempts on Berlin’s Unter den Linden, not far from where Bismarck had been targeted, in the space of less than a month.

–

Two Attempts On Kaiser Wilhelm I

(May 11th 1878 & June 2nd 1878)

Like a desperate gambler, Otto von Bismarck had staked everything on the defeat of Austria in 1866 and won.

With Prussia’s southern foe roundly defeated at the Battle of Königgratz on July 3rd and forced to sign the Peace of Prague later in the month – bringing the war to a close with the Prussians in a much improved international position and clearing a path to German unification.

The German Confederation, an alliance of German-speaking states that had come together after the defeat of Napoleon, was immediately abolished and replaced with the much greater North German Confederation.

Although considered a confederacy of states, the Confederation would be a vehicle for the growing power of its largest member, Prussia – which consisted of 80% of the territory of the North German Confederation.

Four years later, the death of the King of Spain inadvertently provided the opportunity to once-and-for-all resolve the German question, in the eyes of the Prussian government, as Otto von Bismarck carefully stage-managed a confrontation with France over the candidacy for the Spanish throne.

With Queen Isabella II overthrown in 1868 as a result of a popular democratic revolution, the Spain government undertook to find a new monarch and in July 1870 announced that the throne had been offered to German prince Leopold of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen, a distant cousin of Prussian King William I. Sensing the opportunity to agitate the great European enemy – France – Otto von Bismarck would make sure Leopold accepted the offer.

The subsequent objection from France – and fumbled attempt by the French ambassador to Prussia to resolve the matter – would be exploited by Bismarck, who through the doctored release of a telegram sent by Wilhelm I would lead the French to declare war.

The six-month long conflict would end in a devastating loss for the French and a major shift in the European balance of power.

Prussia’s ultimate triumph would be confirmed on January 18th 1871 at the Versailles Palace’s Hall of Mirrors, when King William I was proclaimed Emperor of the German Empire.

Although rather than his image as the embodiment of Prussian militarism or as the founding father of the German Empire, it would be Wilhelm I’s approach to social policies at home that would be the justification for two assassination attempts against him in Berlin in 1878.

With the matter of the ‘German Question’ resolved in 1871, Wilhelm I and his new Chancellor, Otto von Bismarck, faced the task of governing over 27 unified states and the people gathered in four kingdoms, six grand duchies, six further duchies, seven principalities, three free Hanseatic cities, and one imperial territory.

The patchwork railroad network would be greatly expanded across these newly unified states, as cities were rapidly industrialised, and workers flooded into the factories from the fields to fuel Germany’s Industrial Revolution in the late 1800s.

With the growth of the working class, came the desire to have working class interests represented, and Emperor Wilhelm I and Bismarck found themselves fighting a concerted struggle against the spread of socialist principles.

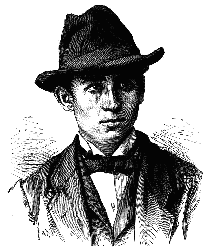

While travelling along Unter den Linden on May 11th 1878, Emperor Wilhelm I was attacked by a young anarchist named Max Hödel at around 3:30pm. Originally from Leipzig, Hödel fired two shots with a Lefaucheux revolver, both of which missed the Kaiser and his daughter – Princess Louise, who was seated next to him in the royal carriage. The German Emperor was at that time just passing by the hotel of the Russian Embassy, on Unter den Linden.

Hödel was chased by a group of around 10 people and caught 250 meters away from the site of the attack – at Mittelstraße 34. Taken to the police station at Molkenmarkt, he was eventually transferred to a prison at Hausvoigteiplatz

Sentenced to death for high treason, he would be executed on August 16th at the Zellengefängnis Lehrter Straße.

The axe used to behead Hödel is on display at the Märkisches Museum in Berlin

As a former member of the Sozialistische Arbeiterspartei (SAP), Hödel was held as an example of the deadly threat of the spread of Socialism, despite the fact that he had actually been expelled from the party for his anarchist leanings.

Whilst imprisoned and waiting for trial, he would hear of another unsuccessful attempt on the life of the Emperor, less than one month after his own attack.

Undeterred by Hödel’s attempt, the Emperor continued to travel along Unter den Linden in an open carriage.

On June 2nd 1878, he was attacked again.

This time from the window of a house on the street – the second floor of Unter den Linden 18 – by an agronomist named Karl Eduard Nobiling. Using a double-barreled shotgun, Nobiling fired at the Emperor whilst he was riding past.

Although hit numerous times in the body, William I survived the blast to the head due to his Pickelhaube helmet.

Several witnesses immediately tried to disarm the would-be assassin and found that Nobiling was also carrying a pistol, which he used to shoot himself in the head.

Incapacitated although not dead, it would take until September 1878 for the doctor to succumb to his injuries.

Unlike in the case of Max Hödel, there was no indication that Nobiling had much support for the political left. Regardless his attempt on the life of the Emperor would be more fuel to the fire Otto von Bismarck was lighting under the socialist movement at the time.

Both of these attacks would be used to justify the Anti-Socialist Law, passed by the German parliament on October 18th 1878, for the purpose of fighting the working-class movement. In the hope of reversing its growing strength, the Social Democractic Party would be banned; all workers associations prohibited; and socialist literate decreed illegal.

The law had originally been proposed on May 15th – four days after Max Hödel’s attack on Wilhelm I – but was voted down on May 24th. Only 57 deputees agreed with the motion, while 251 voted against it.

Despite the government’s attempts to weaken the SPD, the party continued to grow in popularity and after Bismarck’s resignation in 1890 the Law was allowed to lapse by the German parliament, having already been renewed numerous times.

In an attempt to subvert the power of the Social Democratic Party, Bismarck was left to ally with an old enemy – the Catholic Centre Party. The same party that in 1933 would play an integral role in abolishing the Germany democracy that Bismarck had shepherded for much of his political career.

–

The Attempt On Adolf Hitler

(March 21st 1943)

In all likelihood, there is no other political leader who has survived as many assassination attempts as Adolf Hitler.

Between taking power in 1933 and the Nazi leader’s eventual demise twelve years later, it is estimated that Hitler cheated death at the hands of an assassin no fewer than 40 times.

Testament to the lack of complete support of the Nazi Party, its policies and means of achieving its aims, the majority of these attempts are known to have come from within the country – rather than having been authorised or coordinated by the forces allied against Nazi German in the Second World War.

The most celebrated of these attempts carried was out in July 1944 as part of a coordinated plot by a group of officers in the German Army. Commonly referred to as Operation Valkyrie, this attack saw a staff officer named Lieutenant Colonel Claus von Stauffenberg plant an explosive device at Hitler’s Wolf’s Lair headquarters in East Prussia; coming close to killing the Nazi leader and almost triggering the overthrow of the entire government. While Stauffenberg has long since been identified as the key figure in the attack, post-war analysis of documentation gathered in the Soviet Union has revealed that the plan was actually developed by Chief of Staff of the Second Army, Colonel Henning von Tresckow, who had been plotting against Hitler since the autumn of 1941.

Tresckow was involved with a number of previous attempts. On at least two occasions coming close to killing the Nazi leader and calling off the planned attacks when certain important details were taken into account.

Hitler could not be shot; as it was widely suspected that he was wearing a bullet-proof vest.

He could not be poisoned; as his food was tested before being served.

Instead, Tresckow, would concoct numerous plans to blow up the Nazi leader.

On March 11th 1943, with the war on the Eastern Front now clearly not going to plan, Adolf Hitler arrived in Smolensk to visit the German troops in an effort to boost morale.

Tresckow had decided to act.

At first considering the feasibility of ambushing the Nazi leader on his way from the airport, although this was soon abandoned after the presence of his heavily armed SS escort was factored in.

Tresckow’s second Smolensk plan was that a group of officers would all simultaneously shoot the Nazi leader at lunch in the officer’s mess. This was called off, however, when the Commander of Army Group Centre, co-conspirator Günther von Kluge, convinced Tresckow that it was too soon to kill Hitler and that his death would likely not trigger the downfall of the regime, as hoped, but a civil war in Germany, with the SS fighting against the Army.

Tresckow instead decided to utilise a bomb that had been prepared and blow up Hitler on his return flight back to his East Prussian headquarters.

The Colonel handed the bomb, which he claimed to be a bottle of Cointreau liquor wrapped up to be transported to another officer at the Wolf’s Lair to make up for a lost bet, to a Lieutenant Colonel named Heinz Brandt. An unwitting accessory, Brandt would later inadvertently come to save Hitler’s life in July 1944 – when he moved the bomb placed next to Adolf Hitler by Claus von Stauffenberg.

The fact that Hitler survived his return flight from Smolensk was a matter of pure chance.

The bomb, made of plastic explosive, had not detonated, likely because the timer – consisting of a spring which would be gradually dissolved by acid – had malfunctioned due to the low temperature in the cargo hold of the plane. The package was quickly retrieved before any suspicion of the plot could be aroused.

The next attempt, carried out a week later in Berlin, would be one of the few chances that the officers in the German Army conspiring against Hitler would have left to kill him in the Nazi capital.

The Führer was spending less and less time in Berlin as a result of the deteriorating situation on the Eastern Front.

Preferring instead to remain at his headquarters at the Wolf’s Lair near Rastenburg in East Prussia, with occasional breaks at his Bavarian mountain retreat Obersalzberg, near Berchtesgaden. Both of these places were heavily guarded and it was deemed that an attack in either location would be much less likely to succeed than catching Hitler somewhere in the open.

Somewhere like Berlin.

On March 21st, Hitler was scheduled to appear at the Zeughaus, on Unter den Linden, as part of the Heldengedenktag (“Day of Commemoration of Heroes”) public holiday. His first appearance in public in Berlin since the surrender of the 6th Army at Stalingrad.

He would be targeted by his tour guide, who had volunteered to act as a suicide bomber and hurl himself at the Nazi leader, embracing Hitler as the explosives he was carrying in his pockets detonated.

Lieutenant Colonel Rudolf Christoph von Gersdorff had become acquainted with Henning von Tresckow through his work with Army Group Centre, where he served as a liaison for German Military Intelligence during the invasion of the Soviet Union. Given the job of escorting Adolf Hitler around the Zeughaus in Berlin and introducing the Nazi leader to the captured Soviet military equipment on display, Gersdorff volunteered himself to Tresckow to act as a suicide bomber. With Hitler’s appointed successor, Hermann Göring; Reichsführer SS, Heinrich Himmler; Chief of the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht, Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel; and Supreme Commander of the Navy, Grand Admiral Karl Dönitz, set to be present for the ceremony, the hope was that the attack would decapitate the Nazi regime in one fell swoop.

As Hitler entered the museum, Gersdorff took a dose of Pervitin – a methamphetamine mass manufactured by the Nazis and distributed to soldiers – to steady his nerves and set off two ten-minute delayed acid fuses on explosive devices hidden in his coat pockets. Had the attack been successful, a plan was ready to be put into motion that would see control of the country seized by the conspirators.

Adolf Hitler, however, had other intentions.

Departing from the scheduled timetable for this appearance, Hitler raced through the exhibition in around two minutes.

Leaving Gersdorff stood with the live explosives in his pocket; and the fuses slowly dissolving, after unsuccessfully trying to interest the Nazi leader in the artefacts on display.

Managing to excuse himself and head to a public bathroom, Gersdorff removed the acid fuses from the explosives and left the building without drawing any attention to himself.

Walking towards the Brandenburg Gate, the Lieutenant Colonel turned into the Schadowstrasse and entered the Union Club, where – according to his post-war testimony – he met Cologne banker Waldemar von Oppenheim. The two drink and talk and Oppenheim jokingly confides in Gersdorff that he just missed the opportunity to kill Hitler.

“In front of my ground floor room in the Hotel Bristol, he slowly drove past the ‘Linden’ in an open car. It would have been easy to throw a hand grenade into his car across the pedestrian walkway.”

It would appear that Lieutenant Colonel Gersdroff was not the only person to consider killing the Führer that day in March 1943, on Unter den Linden.

The attempts on Hitler’s life on March 11th and 21st 1943 would remain unknown to the world until after the end of the Second World War, luckily for the would-be-assassins, the Nazi intelligence services were completely unaware.

How many other attempts on Hitler’s life remain undocumented? What would a world without Hitler have looked like in 1943, had the attack on Unter den Linden succeeded?

Questions that can never be truly answered.

Certainly of the four assassination attempts on Unter den Linden, the attack on Hitler is more well known. Such is the allure of historical conjecture, it would be fascinating to know what the world would have been like had the Nazi leader met his end inside the Zeughaus in 1943.

Such is the strange course of history, however, it is worth considering whether there would have been a Hitler had Bismarck or Wilhelm I been killed on Unter den Linden less than a century earlier.

More importantly, whether there would have been a Germany at all – had Bismarck succumbed to his wounds in 1866?

**

If you’ve enjoyed reading this article, consider booking one of our private guided tours of Berlin.

Our Related Tours

To learn more about the history of Nazi Germany and life in Hitler’s Third Reich, have a look at our Capital Of Tyranny tours.

Think you already know enough about the rise and fall of the Third Reich? Take our Capital Of Tyranny Quiz and find out.