“The moral danger is never that one might become a victim but that one might be a perpetrator or a bystander. It is tempting to say that a Nazi murderer is beyond the pale of understanding. …Yet to deny a human being his human character is to render ethics impossible. To yield to this temptation, to find other people inhuman, is to take a step toward, not away from, the Nazi position. To find other people incomprehensible is to abandon the search for understanding, and thus to abandon history.”

Timothy Snyder author of ‘Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin’

When British humorist Alan Coren released his latest collection of comedic essays in 1976, he sought to increase his lolling sales by appealing to the high street reader’s predilections. Discovering that books on golf, cats, and the Third Reich tend to be big sellers, he aptly titled his book ‘Golfing For Cats’ (way before the time of internet cat memes) – and shipped it in a gaudy red book-cover with a big black swastika on the jacket.

Despite the opportunistic title and presentation, Coren’s subsequent long-term tenure as editor of the British satirical magazine, Punch, did more to cement his reputation as one of the more provocative – and at times unsavoury – figures on the UK comedy scene. The book has since drifted off into the afterlife – joining the millions of other out-of-print titles that you may be lucky enough to stumble across while deep diving into a charity shop bargain bin. The appeal of catching a reader’s eye – more so perhaps now in the crowded marketplace of ideas on social media – through the utilisation of the vulgar, indecent, and profane, has not changed one iota.

The age of clickbait and chumbox yellow journalism is upon us.

Of course, the pendulum of human interest as it swings between the sacred and the profane has a lot to answer for – by some estimates it has directly accelerated and underpinned the development of technological advancement. Sexual appetite, for example, in our ‘Permissive Society’ serving as a major catalyst for social and economic change. Think of how the global demand for the consumption and creation of pornography supercharged the spread of the video cassette, DVD player, and internet connection.

Progress is hastened by obsession.

But obsession – in the world of clickbait and ‘Golfing For Cats’ – can also be incredibly self-indulgent.

There is an old saying in the British media that looking for a story about Adolf Hitler in a British newspaper is like searching for hay in a haystack.

What has become a rather pedestrian human fascination with the lurid details of criminality peaks in many countries with mere mention of the leader of Nazi Germany – and the appeal of deconstructing what is frequently portrayed as the ‘ultimate evil’.

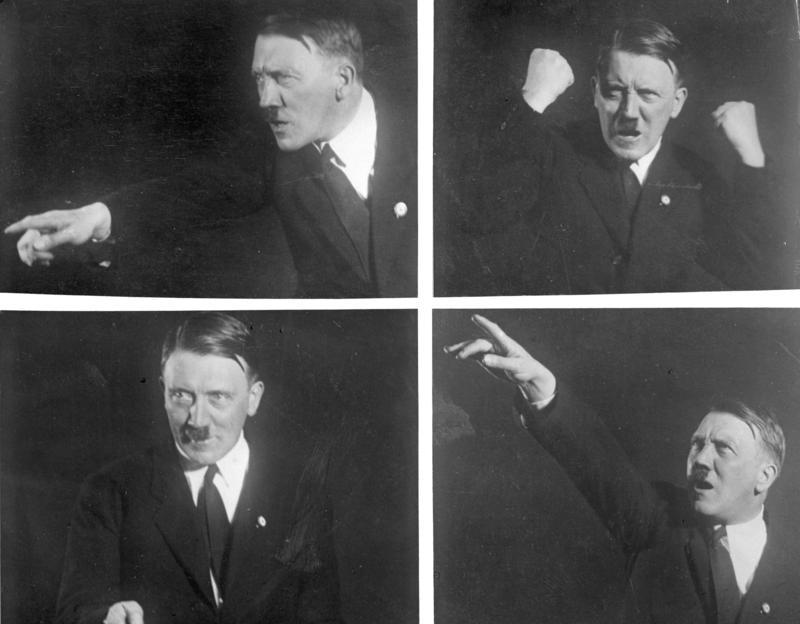

The tyrant is the focus of the Orwellian ‘Two Minutes Hate’ as existential anguish is redirected outwards and the villain is typecast – made archetypical – as much to be disarmed as to be understood. A psychological process of demystification that can be applied to children to overcome fears – such as those of the monster under the bed – is to draw. Adding floppy ears to the monster, or a big smile, to make the beast less threatening. Such a technique falls short when confronting monsters like Hitler, when the silly moustache is already there.

The reality of human tyrants is that they are often all too human – and just like anyone else, prey to human failings, and flawed.

A witch’s brew of accusations have been leveled against the Nazi leader, Hitler’s identity and character; both in his lifetime and since, many of them recognisably absurd – at best an attempt to draw bunny ears on the monster. Most are without doubt driven by the underlying belief that in identifying an individual’s defining characteristics it is possible to detect motive or justification for his or her actions.

The most reductive form of correlation of character as motive.

It need not be more clearly stated that barreling down this road is to indulge the same failing that was at the core of Nazi ideology – and sadly, is recognisably at the core of modern ‘Identity Politics’.

That like an invisible uniform our characteristics and flaws are what define us most clearly. Add purpose to the profile.

No doubt, this is intellectual pauperism – being rich in poor ideas – at its finest. The quack belief that characteristics can be read like tarot cards. That they unveil the holy grail of intentions and motivation. Or simply serve to condemn an individual to the underdeveloped state of their actions – blame assigned to a single character flaw or factor.

The core indicator of Holocaust thinking, where an individual must be viewed first through the prism of identity – and only as postscript can his or her actions be taken into account. Surely, focusing too closely on the actors means risking underrepresenting the importance of the stage.

One of the great biographers of Hitler’s life, British historian Ian Kershaw, would explain Hitler’s unconventional character and style of leadership as being at the centre of an anarchic web of competing departments and interests.

“The chaotic nature of government in the Third Reich was also markedly enhanced by Hitler’s non-bureaucratic and idiosyncratic style of rule. His eccentric working hours, his aversion to putting anything down on paper, his lengthy absences from Berlin, his inaccessibility even for important ministers, his impatience with the complexities of intricate problems, and his tendency to seize impulsively upon random strands of information or half-baked judgements from cronies and court favourites – all meant that ordered government in any conventional understanding of the term was a complete impossibility.”

Hitler’s leadership style was chaotic to say the least, a reflection of his lack of previous political or administrative experience perhaps? Perhaps something more.

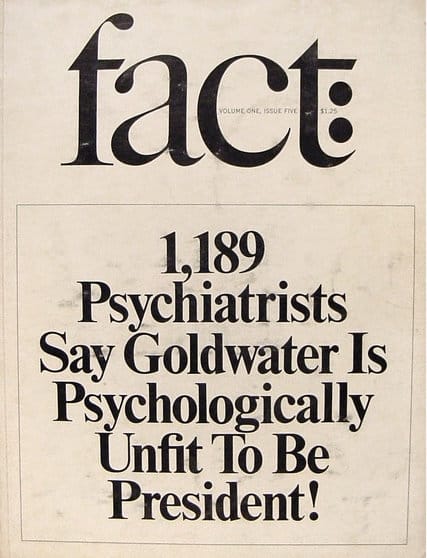

There exists plenty of literature where Hitler has been diagnosed, at least remotely, by psychiatrists and psychotherapists as having mental disturbances: hysteria, psychosis or schizophrenia, narcissistic personality disorder, bipolar disorder, or aspergers syndrome. Although, proffering a professional diagnosis in the media of a figure who has not been directly examined is generally frowned upon by most self-respecting psychiatrists. In the United States, this is known as the Goldwater Rule – named after US Presidential candidate, Barry Goldwater, who successfully sued for defamation in 1967 after being accused of being psychologically unfit for office – and has been part of the American Psychiatric Association’s Principles of Medical Ethics since the 1970s.

Perhaps, if we are to play devil’s advocate and consider a character flaw or characteristic as central to unravelling the Führer enigma, something more simplistic could account for Hitler’s often bewildering outbursts and volatile personality. Something that has been documented and studied – not only in the form of remote diagnosis (such that would fall foul of the Goldwater Rule) but also during Hitler’s lifetime, by those close to him and his personal physicians.

That of an increasingly out of control drug habit.

One of the most controversial books examining this aspect of Hitler’s character and leadership was published in 2015 by Norman Ohler – an amateur historian from Germany, whose writing up to this point had been limited to works of fiction. When translated into English the next year and published under the title “Blitzed: Drugs in Nazi Germany”, the work immediately shot to the top of international bestsellers lists, receiving a warm welcome by some and derision from others, especially more academic historians. Ohler has been accused of lacing the appropriate credentials to complete a historical study – and, worse still, downplaying Adolf Hitler’s role and responsibility in the darkest chapter in German history. For instance, Ohler was sweepingly dismissed as myopic and offering: “more distortion and distraction than clarification” by University of New York history professor, Dagmar Herzog in the New York Times.

Re-examining Kershaw’s above quoted comment, which comes from his highly regarded study ‘The Nazi Dictatorship: Problems and Perspectives of Interpretation’, could it be possible to detect between these lines gaps that would be comfortably filled with the eccentricity of drug abuse and addiction?

Ohler, when interviewed about his book, frequently cites his inspiration for taking on this project as being a conversation with a Berlin DJ about the widespread use of methamphetamine in Nazi Germany – and the drug, Pervitin.

Certainly a study of the part that alcohol played in the rise of National Socialism is well overdue. With beer halls serving as the venues for Hitler’s early rallies, and brewery buildings (such as the one utilised in Oranienburg, near Berlin) repurposed as ‘wild concentration camps’ following the Nazi seizure of power. Plenty has been noted about the use of alcohol by the Einsatzgruppen killing squads to aid in their function, just as its feature in concentration camps and extermination facilities – abused by the guards and functionaries – is well referenced. So why not other more potent poisons – and is Hitler exempt from critique in this aspect?

Examining Hitler’s substance abuse and documented intoxication could undoubtedly go some way to explaining his judgement and actions – even if he was driven by longer-standing and more deeply held commitments and prejudices.

More to the point, rather than simply asking whether Hitler was a drug user, the question here is whether he was an addict. His drug use is well documented. Whether the drugs came to use him more than he used the drugs is the matter at hand.

As American beatnik writer, and self-confessed junkie, William S. Burroughs would write: “The question is frequently asked: Why does a man become a drug addict? The answer is that he usually does not intend to become an addict. You don’t wake up one morning and decide to be a drug addict. It takes at least three months’ shooting twice a day to get any habit at all. And you don’t really know what junk sickness is until you have had several habits.”

Hitler’s drug use is well documented, although the topic has for decades remained a periphery topic in biographical studies it has been covered enough in major studies of his personal life and this period in history to be able to elicit a sense of its importance. The notes of his physicians provide evidence. The eye-witness accounts of his entourage and those who came in close contact with the Nazi leader add further smoke to the gun.

The Nazi regime managed to transform an entire nation in its daily ritual into millions inadvertently wishing health unto their leader. The German word Heil is the imperative form of the verb Heilen (to heal), leading to a popular oppositional response to the ritual greeting of the Führer to respond by asking: “Is he sick?”

He may not have always been sick; but there is little question that he was often high. But how high?

–

High Hitler: ‘Patient A’ & The Medicine Man

“The higher a man rises the more he has to be able to abstain… If a street-sweeper is unwilling to sacrifice his tobacco or his beer, then I think, ‘Very well, my good man, that’s precisely why you’re a street-sweeper and not one of the ruling personalities of the State!”

Adolf Hitler

Hitler’s court consisted of many strong personalities. A wretched kaleidoscope of oddballs and eccentrics, sycophants, and the criminally insane.

A list of characters that anyone aware of the history of the period will know only too well. Men who served and complemented their leader. Enabled his madness, facilitated and implemented his often absurd plans.

Among the more peculiar of these characters (to name but one) was the man who would remain by Hitler’s side almost every day from 1937 until 1945 – his constant companion and personal physician, Theodor Morell. A former ship’s doctor, who had established his reputation as a specialist in venereal disease among the artistic demi-monde of Berlin, Morell entered Hitler’s court by way of treating photographer Heinrich Hoffmann in 1936 for pyelonephritis – an inflammation of the kidney typically due to a bacterial infection.

Morell and his wife would be rewarded with a trip to Venice from his satisfied patient and soon invited to a dinner at the Hoffmann residence in the elegant Munich district of Bogenhausen – attended by Nazi leader, Adolf Hitler.

Morell’s chance to ingratiate himself with the Führer would come after a main course of spaghetti with nutmeg, tomato sauce on the side, and green salad (Hitler’s favourite dish), when the Nazi leader talked in passing about severe stomach and intestinal pains he had been suffering from for years. To which Morell replied that he was aware of an unusual treatment that may provide some relief.

An invitation to join Hitler for further consultation at his mountain retreat in Obersalzberg followed – and thus began one of the most defining relationships of the Führer’s life.

The subsequent meeting near Berchtesgaden led to Morell diagnosing Hitler with abnormal bacterial flora and recommending that a drug called Mutaflor be acquired. Developed by a Freiburg bacteriologist named Professor Alfred Nissle, the medication consisted of a strain of bacteria originally taken from the intestinal flora of a non-commissioned officer who had survived the First World War in the Balkans unaffected by the stomach issues of his comrades. Administered in capsules, the bacteria would take root in the intestine and flourish, replacing all other strains that might lead to further infection.

Bewitched by Morell’s diagnosis and prescription, Hitler promised to not only reward the doctor with a house if Mutaflor did the job but appoint him his personal physician.

Soon Hitler would enter Morell’s records, under a pseudonym – known simply as ‘Patient A’ – and begin to draw the doctor further away from his thriving practice near Berlin’s Kurfürstendamm.

Morell’s list of patients grew as his place in the court became more secure, and Hitler proved more and more approving of him.

Hitler’s digestion improved and with the increase in trust – and the elegant villa on Berlin’s exclusive Schwanenwerder island (next to Propaganda Minister Goebbels) – Morell began administering an assortment of other drugs, fuelled by the Nazi leader’s growing fear that he might not be able to fulfil his functions.

Before speeches, Morell would administer a ‘power injection’, in order to ensure peak performance, intravenous glucose and vitamin injections allowed Hitler to address his troops and people without showing any weakness.

Beyond the addition of Hitler’s mistress Eva Braun (recorded as Patient B), Morell would also treat Benito Mussolini (Patient D), Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop (Patient X), film-maker Leni Riefenstahl, who would be given morphine enemas, Minister of Armaments Albert Speer, and many Nazi Gauleiter and Wehrmacht generals.

Over the course of their nine year acquaintance, the list of substances administered to Hitler by his quack doctor would grow to become almost incomprehensibly long:

Acidol-Pepsin, Antiphlogistine, Argentum nitricum, Belladonna Obstinol, Benerva forte, Betabio, Bismogenol, Brom-Nervacit, Brovaloton-Bad, Cafaspin, Calcium Sandoz, Calomel, Cantan, Cardiazol, Cardiazol-Ephedrin, Chineurin, Cocaine, Codein, Coramin, Cortiron, Digilanid Sandoz, Dolantin, Enterofagos, Enzynorm, Esdesan, Eubasin, Euflat, Eukodal, Eupaverin, Franzbranntwein Gallestol, Glucose, Glyconomr, Gycovarin, Hammavit, Harmin, Homburg 680, Homoseran, Intelan, Jod-Jodkali-Glycerin, Kalzan, Karlsbader Sprudelsalz, Kissinger-Pills, Kösters Antigas-Pills, Leber Hamma, Leo-Pills, Lugolsche Lösung, Luizym, Luminal, Mitilax, Mutaflor, Nateina, Neo-Pycocyanase, Nitroglycerin, Obstinol, Omnadin, Optalidon, Orchikrin, Penicillin-Hamma, Perubalsam, Pervitin, Profundol, Progynon, Prostakrin, Prostophanta, Pyrenol, Quadro-Nox, Relaxol, Rizinus-Oil, Sango-Stop, Scophedal, Septojod, Spasmopurin, Strophantin, Strophantose, Suprarenin (Adrenalin), Sympatol, Targesin, Tempidorm-Suppositories, Testoviron, Thrombo-Vetren, Tibatin, Tonophosphan, Tonsillopan, Trocken-Koli-Hamma, Tussamag, Ultraseptyl, Vitamultin, Yatren.

The italicized names are the psychoactive, consciousness-changing drugs on a list that includes steroids, quack remedies, and balms. The effects of each of these drugs would without doubt alter Hitler’s physical state and at least inadvertently guide his decision making.

Dr. Koester’s Anti-Gas Pills, for instance, which Morell had Hitler taking in large numbers almost every day, were portrayed as an innocent method in taming the Nazi leader’s stomach and intestinal issues by his quack doctor. The pills would, at the least, be mildly harmful and contain strychnine and belladonna, the strychnine suspected by his other physicians as being the cause of the jaundice that Hitler would sometimes experience. Or might have been typical junkie hepatitis because Morell wasn’t using properly sterilised needles?

Measuring the real world consequences of Morell’s toxic relationship with the Nazi Führer is an impossible task, although his impact would be unquestionable.

Morell would even play a direct role in aiding Hitler’s political maneuvering and aspirations for territorial expansion in 1938, when the President of Czechoslovakia Emil Hacha was confronted by Hitler, Göring and Ribbentrop with a simple ultimatum: allow German troops to march into Czechoslovakia in a peaceable manner or face annihilation. In his role of head of the German air force, Hermann Göring threatened to destroy Prague by bombing and Hacha fainted – only to be revived by Dr Morell, who had been kept closely by.

Once conscious Hacha telephoned the Czech government and arranged that there would be no resistance to the German advance. Hacha and Hitler had sealed Czechoslovakia’s fate: and Morell’s needle had played a starring role in this treacherous performance.

Hitler’s drugs – prescribed anonymously, when a prescription was issued – would be acquired from the Engels chemist in Berlin until the pharmacist there became more demanding of the regulations in line with Germany’s narcotics drugs act. This would simply prompt the entrepreneurial Morell to expand his own business ventures and start producing the drugs himself with Hitler’s aid.

Morell would also use Hitler as his guinea pig; seeing the success of his applications and due to his position, Hitler would directly grant the doctor the opportunity to mass produce and sell them without the need for certification. Hitler’s approval – and his survival – would suffice.

A brand of vitamin chocolates would prove a particularly successful venture, as would his lice-powder – made compulsory throughout the armed forces despite being proved to be completely ineffective.

Hugh Trevor Roper, the British historian turned intelligence officer tasked with investigating Adolf Hitler’s suicide in the immediate aftermath of the war, would describe Morell in no uncertain terms as a charlatan:

“He was totally indifferent to science and truth. Rather than study the slow methods of patient research, he preferred to play with quick drugs and fancy nostrums; and when critics hinted at the inadequacy of his qualifications, he merely extended his claims in the empire of lies.”

Morell would even maintain that he was the sole discoverer of penicillin, and that the British secret service had stolen his secret, and allowed a British doctor to take the credit.

The interdependence between Morell and Patient A would ensure the longevity of their relationship – where the quack doctor required the approval of his most important patient to continue in his function as a successful businessman and physician, and Hitler required the constant presence of Morell and his potions sometimes simply to function.

The idea of Hitler as a teetotaler and health-conscious protector of the nation was incredibly useful for the Nazi Party and the image of the Führer. The reality, as was often the case in Nazi Germany, would be different in practice than in promise.

–

Drugs In Deutschland: From Morphine & Cocaine to Pervitin & Eukodal

“You must be healthy, you must stay away from that which poisons your bodies. We need a sober people! In future the German will be judged entirely by the works of his mind and the strength of his health.”

Adolf Hitler

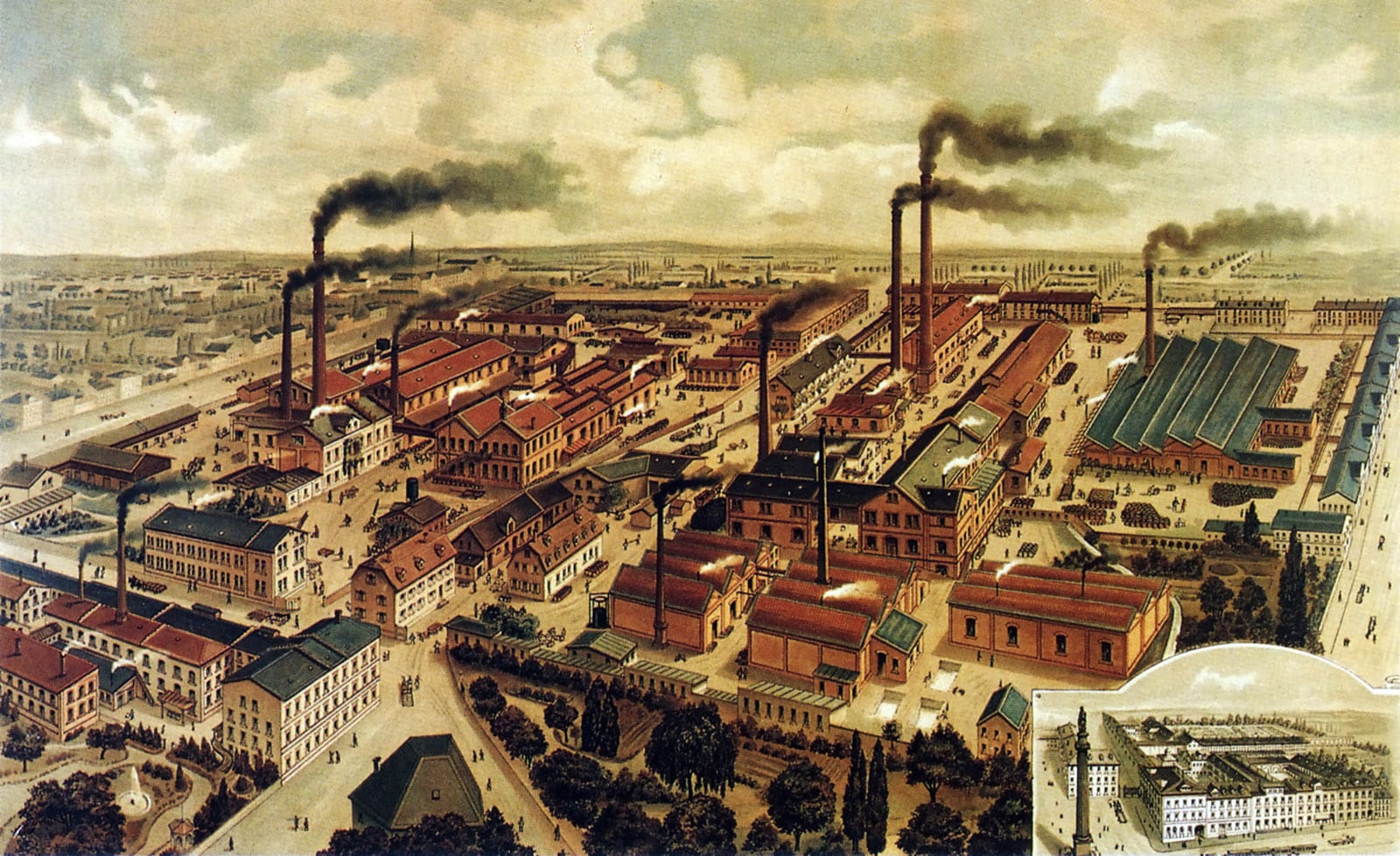

As the modern pharmaceutical industry grew in the 19th century, German chemists would play a starring role in the medicinal milestones of the period. With German companies, harvesting the bountiful crop of university educated scientists cultivated in the country to quickly become global leaders in the trade.

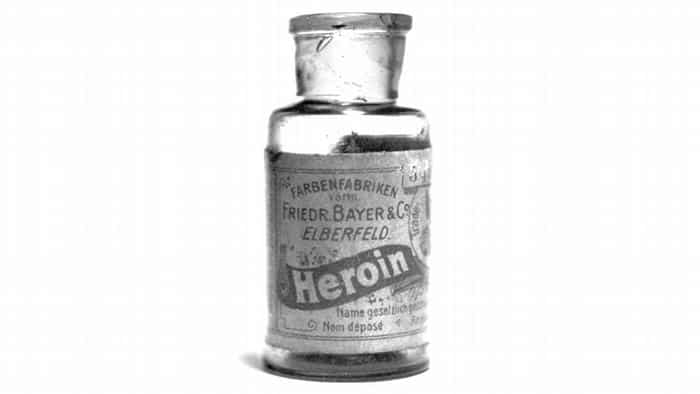

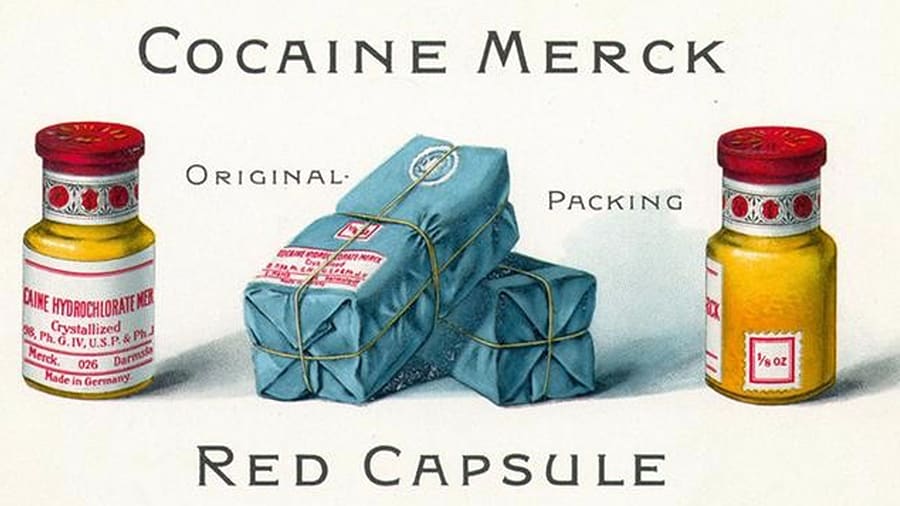

Two developments in particular, at the start and middle of the 19th century, would come to define the success of this industry – the isolation of morphine by Friedrich Wilhelm Sertürner in 1804 and the isolation of cocaine in 1855 by Friedrich Gaedecke.

By the 1920s, two German cartels – known as the ‘opiates convention’ and the ‘cocaine convention’ – would dominate the international market in these drugs. Companies like Merck, Boehringer, and Knoll controlled 80% of the world cocaine market – with thousands of kilograms of raw cocaine arriving at the Port of Hamburg every year; and Peru selling almost its entire yield of cocaine to German companies for processing. Similarly, between 1925 and 1931, 40% of all morphine production would come from German companies.

Beyond the extent of their medicinal application, recreational use of these two drugs, in particular, would boom in the century following their discovery.

Morphine to calm the nerves; cocaine to induce euphoria.

Cocaine produced by Merck, which had its headquarters in the German city of Darmstadt, was seen as the best in the world – and Chinese pirates would print fake Merck labels by the million.

The toxicological frenzy of Germany’s Weimar Republic era would reach unheard of heights fuelled by German drug manufacturers, who kept the country swimming in consciousness altering and intoxicating substances. Artificial paradises were en vogue, and the ‘Whore of Babylon’ as the city was described as in Alfred Doblin’s classic novel of the era Berlin Alexanderplatz needed her fix.

In 1928 alone, 73 kilos of morphine and heroin were sold legally in Berlin on prescription over the chemists counter.

Both dominant parties of the extreme of the era – the Nazis and the Communists – railed against this pharmacological quest for liberation through intoxication. Alcohol was often enough for the masculine rituals of street brawling and tub-thumping sloganeering.

As the National Socialist movement grew, it positioned itself against the decadent western excesses of drug use and abuse – and, much as the Bolshevik regime in taking power in 1917 in Russia would seek to supercede religion and the church with its own rituals and imagery, the Nazi Party would sneer at the intoxication culture of the Weimar era. Preferring instead the ideological palliative of National Socialist salvation. Seductive poisons had no place in the Nazi world view where the Führer was expected to do the seducing.

The stigmatisation of drug use and the punishment of users and addicts arrived as quickly as the Nazi regime in 1933. By the end of the year, a law was passed that allowed for imprisonment of addicts in a closed institution for up to two years – which could easily be extended indefinitely by legal decree.

A ‘duty of health’ would be expected from the population, drug addicts would be forced to go cold turkey if found by a panel of two doctors to have ‘hereditary factors’ which inclined the patient to drug use. Narcotic addicts would be forbade marriage and even forcibly sterilised – some of the around 400,000 cases of forced sterilisation that the Nazi state would carry out.

Department II of the Reich Health Office in Berlin – the Reich Committee for the People’s Health – would oversee the implementation of Nazi drug policy. By 1941 the ‘Reich Central Office for Combating Drug Transgressions’ would be established, and functioned under the direction of SS Hauptsturmfuhrer Criminal Commissar Erwin Kesmehl.

While consumption of the more traditional intoxicants, such as heroin and cocaine, would fall as a result of the Nazi ‘War on Drugs’, pharmaceutical companies would acquire a new purpose – in producing synthetic stimulants, the kind of drugs that could be produced independently from imported materials and prove useful for the coming European confrontation that Hitler and his regime was speeding towards.

The introduction of the 19th century German drugs – particularly morphine – would have a huge impact on the battlefield and transform how armies would fight forever. Through narcotic intervention these armies could transform their soldiers into superhuman killing machines. Fueled by amphetamines and patched up with opiates. From the introduction of injections to administer drugs in 1850, the production and application of morphine would enable armies to quickly revitalize their injured soldiers, importantly, enough to muster again a frontline force. Even if these piecemeal walking dead were destined to serve as drugged cannon fodder.

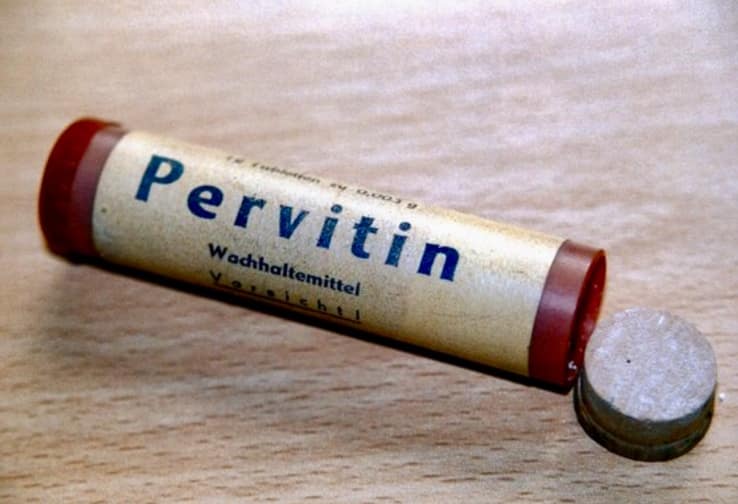

In 1937, a German company named Temmler would find a new method of synthesising methamphetamine – which had been discovered by Japanese researchers as early as 1887 and crystalised in 1919. Developed out of ephedrine, this Japanese drug clears the bronchia and stimulates the heart.

The new Temmler drug – trademarked as Pervitin – would become a performance enhancing drug fit for the Nazi era.

Marketed as a wonderdrug, Pervitin was said to compensate for the withdrawal effects of alcohol, opium and cocaine, aid circulation, low energy, and fight depression. Sold in an iconic orange and blue tube, in pill form, it would be produced under industrial laboratory conditions en masse in Berlin.

Embraced by secretaries and workers, writers and actors, doctors and students, Pervitin consumption would boom following its introduction to the market – a symptom of the developing performance society.

As Nazi propaganda called for Germany to awaken (Deutschland erwache!), Pervitin ensured that the country stayed awake.

As civilian use of the drug skyrocketed, certain individuals within the German Wehrmacht began to pay attention to the benefits of its consumption and possible military application. While no immediate order was given for its mass deployment, Pervitin would turn up during the Nazi conquest of Poland in 1939 and its use and misuse convince the German military to implement its widespread distribution throughout the ranks.

From 1939, Pervitin use would be restricted and then regulated two years later with the Reich Opium Law. The regulation however only concerned civilian society and not the military; and many pharmacists would continue to give their customers hospital packs of Pervitin without the necessary paperwork.

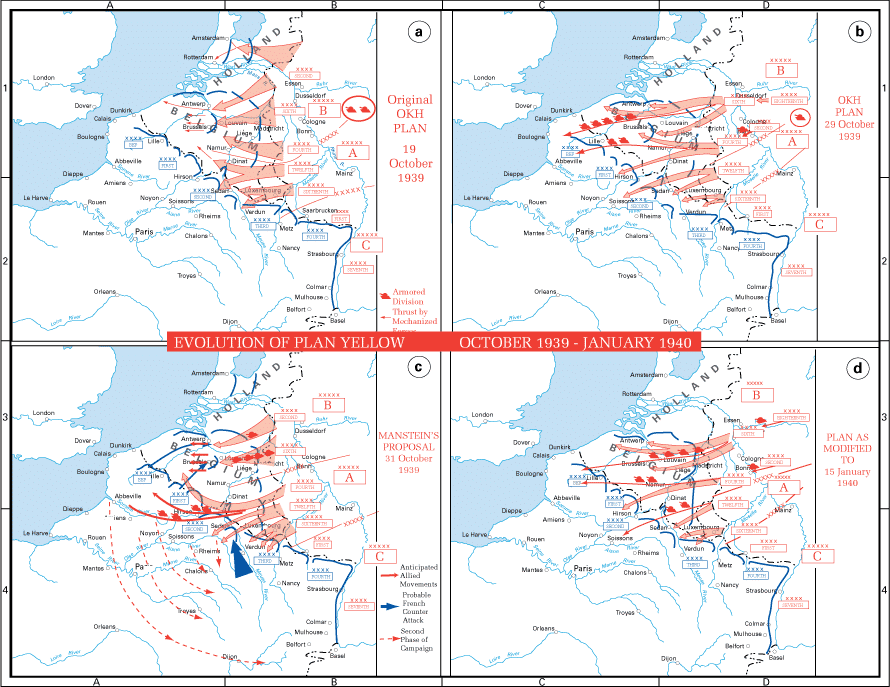

On February 17th 1940, Reich Health Führer, Leo Conti, wrote a letter of protest to the German army medical authority, objecting to the use and abuse of Pervitin by the military. Coincidentally, the same day, Adolf Hitler met with generals Erich von Manstein and Erwin Rommel to finalise the plans for the invasion of France – agreeing on an audacious push through the Ardennes. An operation that would be highly dependent on speed to maintain the element of surprise necessary to catch the French and British on the back foot.

To ensure the success of this ‘sickle cut’ through the Allied front lines, it would be necessary for the German troops to drive day and night – without stopping – improving on their rapid movement tactics executed to great success in Poland. The term, Blitzkrieg – which would come to be synonymous with the doctrine of modern maneuver warfare on the operational level and the rapid advance of mobile combined arms formations – was used by English and German language press during the Second World War but never embraced by the German military. Mass consumption of a chemical inducement such as Pervitin would exponentially increase the likelihood of success of this ‘lighting war’ tactic, reliant as it was on surprise penetration and the inability of the enemy to match the pace of the German attack.

In April 1940, Prof. Dr. Otto F. Ranke – the leading defence physiologist in the Third Reich – and commander-in-chief of the German Army, Walther von Brauchitsch, co-authored a document that would provide the basis of the use of stimulants in the military – the so-called ‘Stimulant Decree’.

Sent to thousands of doctors and medical officers it stated, in clear terms, the intention of the German Army to embark on a new kind of war – as the first army in the world to rely on a chemical drug.

“The experience of the Polish campaign has shown that in certain situations military success was crucially influenced by overcoming fatigue in a troop on which strong demands had been made. The overcoming of sleep can in certain situations be more important than concern for any related harm, if military success is endangered by sleep. The stimulants are available for the interruption of sleep. Pervitin has been methodically included in medical equipment.”

Between April and June 1940, the German Wehrmacht would receive and distribute 35 million doses of Pervitin to its troops.

Consumption in the general population had risen to around a million doses a month when the drug was reclassified as an intoxicant and prohibited as a result of the Reich Opium Law. The lonely battle that the Reich Health Führer, Leo Conti, fought against Pervitin consumption was one he was bound to lose, however, as use grew in the following years. Although this low level consumption would be dwarfed by the figures listed by the military – and just as surely allow for better allocation to fuel the war effort.

The date chosen for the introduction of the ban, in which case, could not have been more fortuitous; as Germany was destined to invade the Soviet Union ten days later and embark on the bloodiest episode of its toxic war.

–

The Toxic War - Medicating The Madness

“Presenting the Reich Chancellor as ostensibly a pure person, remote from all worldly pleasures, entirely without a private life. An existence apparently informed by self-denial and long-lasting self-sacrifice: a model for an entirely healthy existence. The myth of Hitler as an anti-drug teetotaller who made his own needs secondary was an essential part of Nazi ideology and was presented again and again by the mass media. A myth was created which established itself in the public imagination, but also among critical minds of the period, and still resonates today. This is a myth that demands to be deconstructed.”

Norman Ohler, author of Blitzed: Drugs In Nazi Germany

By 1942, the tide of war was truly turning again Nazi Germany.

The previous year had ended with an attack on Moscow, the capital of the Soviet Union, but ‘Operation Typhoon’ – as the Battle of Moscow was codenamed – would soon grind to a halt and be abandoned as a result of a successful Soviet counteroffensive in December 1941. The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour also brought another enemy into the fray, as Hitler declared war on the United States in the late stages of the Battle of Moscow.

The invasion of the Soviet Union had initially taken place on a front almost 3,000km wide – and taken the Soviet leadership by surprise. The ferocity and purpose of the Nazi advance, fighting against an unprepared and partially demobilised state, took German troops 650km into Soviet territory within the first month – and only 200km from Moscow.

If 1941 was the year of rapid advances, pincer movements, and the gigantic encirclement of hundreds of thousands of Soviet troops – soon to become wretched prisoners of war, destined for mass murder and to serve as fodder for the gas chambers – the year that followed would be where it all started to really fall apart.

In July 1942, the reach of National Socialism extended from the North Cape of Norway to North Africa and the Middle East. Hitler shifted his headquarters from the Wolf’s Lair in Poland to a brand new headquarters near Vinnytsia in rural Ukraine around the same time as the systematic killing of Jews, Sinti and Roma, and other ‘undesirables’ as part of Operation Reinhardt began to take its final form as industrialised mass murder.The year would come to a close with the German Sixth Army in Stalingrad – the city that bore the Soviet leader’s name, with which Hitler would develop a psychopathic fixation – encircled and destined for near annihilation.

Hitler’s doctor, Morell, would register a four word description of the Nazi leader’s condition on December 9th 1942 – as 265,000 Axis troops remained encircled in Stalingrad: “intestinal gases, halitosis, discomfort.”

The Army General Staff had been convinced that Moscow should remain their main objective, determined that a decisive battle would be fought for the Soviet capital to deal a death blow to the Bolshevik enemy. Hitler had a different strategy, that involved dividing the frontline, with the northern troops assigned to conquer Leningrad and Army Group South tasked with advancing through Ukraine to the Caucasus to take the oil resources.

A plan which would fail to bring about the defeat of ‘the Bolshevik foe’.

As the outlook of the war on the Eastern Front turned from bad to worse, the Nazi leader’s health undertook a similar process of deterioration – leading to Adolf Hitler’s eventual demise in 1945.

Dr Theo Morell, who had been a familiar face at the court of the Nazi dictator from 1937 onwards – would become an essential presence from 1939 to mitigate the effects of Hitler’s psychological and physical exhaustion and ensure that a chemical balance be maintained that would allow Hitler to shepherd the direction of the war.

The victories in Poland and France brought about ecstatic celebrations, jubilation throughout the Reich that this fresh new leader had done the impossible and defeated not only Germany’s eastern Polish neighbour state but also mighty France – and in fewer than eight weeks!

The war in the East, however, would be a different conflict altogether – an ideological clash of civilisations. A war that would be fought from top to bottom in the Nazi regime, and within the Nazi war machine, enhanced by the use of pharmacutical aids.

Hitler’s changing role as Nazi leader followed six years of public adulation and ovations; he would largely remain isolated at his military headquarters in the East and turn away from his previous form of beloved public speaker. Pharmaceutical indulgence would come to replace the mass jubilation of the crowd. The bunker mentality of the intoxicated cave dweller would have to suffice. Close to the front but far removed from the realities of war.

Hitler would, in the later years of the war, split his time between three locations – the Wolf’s Lair (a top-secret, high security military facility near the East Prussian town of Rastenburg), the Werewolf (the easternmost of Hitler’s military headquarters, near Vinnytsia in Ukraine), and eventually the Führerbunker (his underground bunker in Berlin).

The worse the situation got; the deeper Hitler’s quack doctor dug into his bag of tricks for more elaborate solutions.

In August 1941, for example, when Hitler fell ill at the Wolf Lair, Morell was called upon to revive ‘the Boss’ – administering a mixture of Vitamultin and calcium, combined with the steroid gylconorm – a hormone preparation that he had manufactured himself from the cardiac muscle, adrenal cortex, liver and pancreas of pigs and other farm animals. This concoction essentially a designer doping agent devised to ensure that the Führer could attend to his rigorous schedule and lead the daily military briefings that were taking place at a crucial junction in the war on the Eastern front.

The changing fortunes of the war from 1942 would see a transition from Blitzkrieg advances to the wholescale prescription of ‘fanatical resistance’ amongst the troops and general population. Allied air attack would increase on the home front: graduating from attacks on factories and military targets to carpet bombing and terror attacks on entire cities. Rommel’s defeat in Africa, the disaster of Stalingrad and the Caucasus campaign, and a submarine battle in the Atlantic the Germans were losing.

As the war of swift advances turned into a war of attrition, Pervitin became less useful – sleep deprivation and going the extra mile for the final stretch was no longer relevant. Sleep and exhaustion could only be delayed for so long before soldiers would succumb to these powerful forces.

It is around this time that Hitler likely began to succumb to the effects of polytoxicomania (his increased reliance on multiple drugs taken altogether or sequentially, depending upon their availability). Drug tolerance builds with consumption, and doses have to be increased as the body accustoms itself to substances – either the dose increases or the effect declines.

Hitler’s court architect, Albert Speer, would comment on the Nazi leader’s relationship with his physician, saying: “Morell managed to cover up his exhaustion by means of artificial stimulants, a method which ends by completely ruining the patient. Hitler became accustomed to these means of keeping up his endurance, and kept on demanding them. He admired Morell and his methods, and was in some sense dependent on him and his remedies.”

Rather than looking to keep the Nazi leader in his trademark mania, Morell would assume a new role when attending to Hitler in these three locations: that of calming the increasingly frustrated Führer and saving his nerve. ‘Patient A’ would even be advised to knock back a beer or slivovitz to help, so far as it had been analysed by a field laboratory in advance.

On July 18th 1943, following the failure of the German Operation Citadel, aimed at the Kursk salient, Morell was called upon in the middle of the night to produce an immediate cure to the Führer’s suffering. Discovering Hitler bent double with pain and suspecting that the white cheese and roulades with spinach and peas from dinner had disagreed with him, Morell struggled to find the right substance to relieve the pain. Hitler was set to attend an important meeting with the Italian leader, Benito Mussolini, the following day, that was no doubt going to be tense – as the Allied forces had already landed on Sicily and Hitler was concerned that the Italians might switch sides.

The ace up his sleeve that Morell reached for was a drug manufactured by the German company, Merck, and sold under the trademark name, Eukodal. The active ingredient in Eukodal is an opioid called Oxycodon, which was synthesised from the raw material of opium by two German scientists in 1916 – Martin Freud and Edmund Speyer.

The latter of these two scientists died in May 1942 – the year the wheel turned all the way around for National Socialism – as a German Jew deported by the Nazis to expire in the Lodz Ghetto in Poland.

An additional shot of Eukodal would be administered before Hitler boarded his flight to meet Mussolini – the first having proved so successful. Injected under the skin, this nectar of the gods had immediately solved Hitler’s violent spastic constipation and giving him a sudden burst of energy and enthusiasm about meeting the Italians.

Almost twice as painkilling as morphine, Eukodal also provides the user with a euphoric state significantly higher than heroin, its pharmacological cousin.

Compounding Marx’s dictum that religion is the opium of the masses, Hitler would discover that opium is also the opium of the masses. As the British had proven to the world in the 19th century. Although whether Hitler was even particularly aware of what exactly he was taking is questionable – so certain was his trust in Morell. Twenty four applications of Eukodal are recorded in Morell’s physician’s notes up to the end of 1944 – although in many instances he would simply record an ‘X’ on his sheet or remark ‘injection as always’ – which leaves a huge gap in the record of what exactly Hitler was taking beyond what was recorded.

Oxycodon use is incredibly dangerous, as even a quack like Morell would have been aware of, and two or three weeks of regular use can not only make a person physically dependent on it but rewire their approach to the mortal world.

German philosopher Walter Benjamin, describing the sense of intoxication he experienced from taking drugs (including orally administered Eukodal), would present an eerily familiar picture to that which appears to have taken place in Hitler’s final years.

“It is perhaps no self-deception if I say that in this state you develop an aversion to open air, the (so to speak) Uranian atmosphere, and that the thought of the outside becomes almost a torture. It is a dense spider’s web in which the events of the world are scattered around, suspended there like the bodies of dead insects sucked dry. You have no wish to leave this cave. Here, furthermore, the rudiments of an unfriendly attitude towards everyone present begin to take shape, as well as the fear that they might disturb you, drag you out into the open.”

The introduction of Eukodal would not supersede the many other drugs administered regularly to ‘Patient A’ but rather compliment them. And many there were.

For Hitler’s 55th birthday on April 20th 1944, Dr Morell administered a concoction of Vitamultin, forte, camphor and the plant-based coronary prophylactic Strophanthin – followed the next morning by an injection of Prostrophanta, a concoction for heart conditions.

The celebrations were interrupted by an air raid and the artificial fog station at the Berghof residence was turned on: cloaking the residence with an artificial whiteness.

On June 6th 1944 – the day the Allied landings at Normandy took place – Hitler received another dose of his X medication from Morell to calm him down in spite of the looming military disaster. After lunch he would again regale his captive audience with the story of his visit to an abattoir in Poland, and his disgust at seeing girls wade in rubber boots through blood that would have reached up to their ankles. His vocal advocacy of vegetarianism was no match, however, for Morell’s medication – and following this reminiscing Hitler would be injected with a substance made from the glans of slaughtered animals. As usual, the Nazi leader showed no sign of registering the hypocrisy. Hitler raving about eastern european abattoirs was a frequent topic of conversation; whilst Morrell is buying up all the organs and glands from every facility in the region.

Pumping Hitler full of drugs would continue to be a profitable business for Morell; as the heart of the Nazi regime was by the hour coming closer to succumbing to its toxicity.

Between July 22nd and October 7th 1944, another wonderdrug would enter Hitler’s bloodstream – as a result of his condition following an assassination attempt on July 20th at the Wolf’s Lair headquarters. Due to injuries to both Hitler’s eardrums, an ENT specialist named Dr Erwin Giesing would arrive with his favorite remedy for treating pains in the ear, nose, and throat: cocaine. Dismissed by the Nazis as a ‘Jewish drug’, this high quality Merck cocaine arrived in an extremely psychoactive 10% solution and would be administered to Hitler more than 50 times over these seventy-five days.

Naturally, Hitler was a little suspicious and addressed Giesing, saying: “Please don’t turn me into a cocaine addict.” To which the doctor explained that cocaine addicts snort dry cocaine, whereas Hitler would only receive nose swabs.

It was in the midst of this cocaine treatment that Hitler concluded on the idea of a new offensive in the West, a second Ardennes. If the account given by Giesing is correct, Hitler also suffered a cocaine overdose on October 1st 1944, where he lost consciousness for a short time, experiencing possible respiratory paralysis.

There would be other doctors in Hitler’s life, but Theo Morell would remain his favourite.

In March 1945, Hitler would confide in his secretary: “I am lied to on all sides, I can rely on no one, they all betray me, the whole business makes me sick. If I had not got my faithful Morell I should be absolutely knocked out…what would become of me without Morell…”

He would remain at Hitler’s side, accompanying him back to Berlin and the Führerbunker, until his dismissal on April 22nd – by this time the drug supply had dwindled to almost non-existent and his presence was hardly required much longer.

The removal of Morell as Hitler’s little helper and constant companion cannot have had a positive impact on his health, when weighed against the kind of dependence his body must have developed on Morell’s potions and concoctions. The Eukodal, Pervitin, and the cocaine applications administered by Giesing – in particular – would have left their mark.

In the end, it would be Morell – as one of the members of Hitler’s Führerbunker entourage – who would provide the cyanide capsules which Eva Braun would later use to kill herself, and which Joseph Goebbels and his wife Magda used to murder their six children before killing themselves on May 1st 1945.

Hitler’s quack physician would survive the war to be imprisoned in Dachau concentration camp and interrogated by the Americans – acquitted of war crimes he was given a release note (number 52160) and dropped off at Munich train station in 1947 wearing an old american army coat, a few american socks and a shirt that was several sizes too small. He would be discovered by Red Cross workers two hours later: his hair tousled, his face pale, and clutching a note to the effect that he suffered from serious heart problems; that he was unable to work and suffered from an aphasic speech disorder as a result of brain damage.

He died in a clinic in Tegernsee on May 26th 1948 – ‘like a stray dog’, as described by his former assistant.

**

Conclusion

It would be naive to think that proving clinical addiction would be possible now, even with medical records and eyewitness accounts, when lacking the patient to study directly.

Hitler’s fate in 1945 – contrary to any belief that he may have escaped to Argentina – denied investigators and physicians the opportunity to diagnose him of any physical, mental, or psychiatric issues.

Not to mention, how it denied the victims of his crimes the opportunity to see some kind of justice be served.

Referring to Adolf Hitler as a drug addict, however, might not seem such a huge step to take from ‘multiple and frequent drug user’. The difference between physical dependence and psychological dependence would be hard to prove now; although certainly the term ‘drug use’ perhaps even ‘drug abuse’ would apply. Whether Hitler was ever truly aware of the variety of substances Morell was pumping into his body or not.

The affect of these substances undeniably had a profound relationship to the development of the war and the implemention of Nazi Party strategy – as far as Hitler’s involvement was concerned. And in the Nazi sense of hierachy, the man was at the top of a very large pyramid. It would be ridiculous to deny this impact; just as ridiculous as the critique that highlighting his drug consumption as part of his character and decision making process is tantamount to pronouncing that it is the ONLY aspect of his life necessary to understand his actions.

Beyond the effect of the drugs on his person, and his decisions, there is also the matter of the effect on those around him – who were expected to also make important decisions, and seemingly equally as eager to be as ‘medicated’ as the Boss.

In the words of Norman Ohler, author of Blitzed: “What we do know is that if Hitler’s visitors needed exponentially harder drugs to withstand the pressure in that meeting room, this further reinforced an atmosphere of augmented reality in the inner circles of the Nazi leadership. The long-term consumption by Patient A, which no one was allowed to know about, was contagious. Hitler’s multi-addictive presence replaced any relationship with reality among all the people in his immediate entourage.”

Nazi Germany was a carefully stage-managed state – where dissent was destroyed and sacrifice demanded. To maintain such a theatrical fantasy world required a herculean effort of commitment to realising ideological goals. The potential debate of whether the Nazi worldview and Hitler’s intentions were pre-existing or came about due to some narcotic intervention on the part of Hitler’s doctor is not necessary.

Certainly Hitler needed his drugs to be himself, more than himself, and no less. But the apple was rotting far before the worm arrived.

Even if Morell and drug abuse was responsible for the worst of Hitler; these things did not arrive until after 1938 – all evidence points to the fact that Nazi ideology in its racist and imperial worldview was sufficiently formed by this time to provide indication of what would follow.

Our Related Tours

To learn more about the history of Nazi Germany and life in Hitler’s Third Reich, have a look at our Capital Of Tyranny tours.

Think you already know enough about the rise and fall of the Third Reich? Take our Capital Of Tyranny Quiz and find out.

Sources

Beevor, Antony (2003) Berlin: The Downfall 1945, Penguin Books, ISBN 978-0-14-028696-0

Bullock, Alan (1962) Hitler: A Study in Tyranny. New York: Penguin Books.ISBN 978-0-14-013564-0.

Brisard, Jean-Christophe; Parshina, Lana (2018) The Death of Hitler. Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0306922589.

Doyle, D. (2005) Adolf Hitler’s Medical Care (PDF), “Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh”, 35, pp. 75–82.

Eberle, Henrik; Uhl, Matthias, eds. (2005) The Hitler Book: The Secret Dossier Prepared for Stalin from the Interrogations of Hitler’s Personal Aides. New York: Public Affairs. ISBN 978-1-58648-366-1.

Evans, Richard J (2003) The Coming of the Third Reich. ISBN-13 : 978-0141009759

Evans, Richard J (2005) The Third Reich in Power, 1933–1939, London: Allen Lane

Evans, Richard J (2008) The Third Reich at War: How the Nazis Led Germany from Conquest to Disaster, London: Allen Lane

Fest, Joachim (1973) Hitler (ISBN 0-15-602754-2)

Hitler, Adolf (1999) Mein Kampf: Translated By Ralph Manheim ISBN-13 : 978-0395951057

Irving, David (1983) The Secret Diaries Of Hitler’s Doctor (ISBN-13 : 978-0025582507)

Kershaw, Ian (2015) The Nazi Dictatorship: Problems and Perspectives of Interpretation ISBN-13 : 978-1474240956

Kershaw, Ian (2001) Hitler, 1936–1945: Nemesis. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-04994-9.

Mayo, Jonathan (2016) Hitler’s Last Day: Minute by Minute , Emma Craigie | ISBN: 9781780722337

Ohler, Norman (2016) Blitzed: Drugs in Nazi Germany, ISBN 0241256992

Picker, Henry (1963) Hitlers Tischgespräche im Führerhauptquartier (“Hitler’s Table Talk“)

Sappol, Michael (2012) Hidden Treasure: The National Library of Medicine

Shirer, William L. The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. ISBN 978-1451651683.

Trevor-Roper, Hugh (1947) The Last Days of Hitler