“I had nothing to do with it. I deny this absolutely. I can tell you in all honesty, that the Reichstag fire proved very inconvenient to us. After the fire I had to use the Kroll Opera House as the new Reichstag and the opera seemed to me much more important than the Reichstag. I must repeat that no pretext was needed for taking measures against the Communists. I already had a number of perfectly good reasons.”

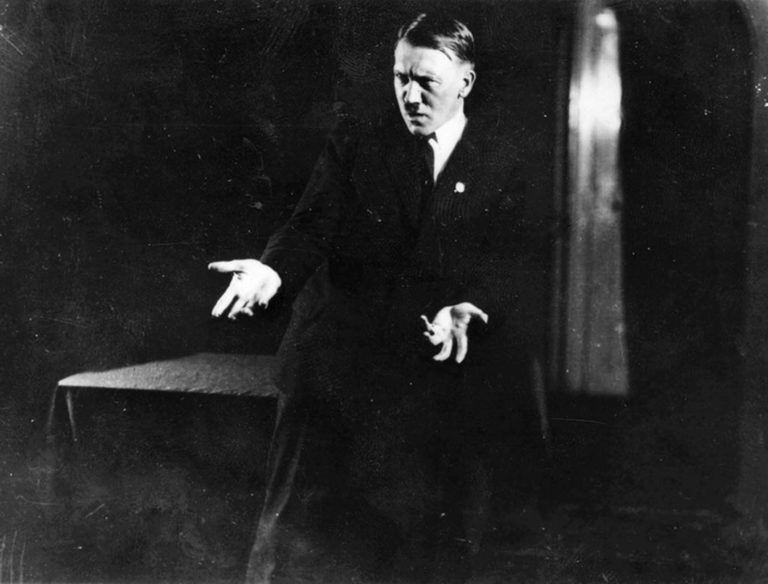

Hermann Göring – founder of the Gestapo, Prime Minister of Prussia & head of the Nazi Airforce

Regardless of the perpetrators of the Reichstag fire, the result was clear: it would be the funeral pyre of Weimar democracy, usher in the opening chapters of National Socialist state terror, and lead to a further consolidation of power around Nazi leader, Adolf Hitler.

On February 27th 1933, Hitler had been Chancellor for fewer than four weeks. His control of the government extended uncomfortably beyond the three of thirteen cabinet seats occupied by the Nazi Party – which held no majority in parliament. The seats held, however, by the conservative coalition partners the Nazi Party was attempting to rule alongside were at this point firmly in Hitler’s sights: as President Paul von Hindenburg had already dissolved parliament and set the date for a new election – March 5th. Hitler hoped the result would change the composition of the cabinet in the Nazi Party’s favour.

Was a democratic transition of power finally in sight?

The results of that election – six days after the Reichstag fire – would still leave the Nazis thirty six seats short of a parliamentary majority with 43.9% of the vote. Despite the violent repression of political opposition: as thousands of Communists, Social Democrats, and political enemies were detained, many tortured, some murdered, by the Nazi brownshirt militia – the Sturmabteilung – and the German police. Legal repercussions, in the form of the suspension of civil liberties and suppression of publications not considered friendly to the Nazi cause, would further pave the way for the establishment of a one-party state.

The complete takeover of power by the Nazi party would not start or finish with the Reichstag fire. But the fallout would forever change the destiny of German democracy.

The verdict of who was responsible for the Reichstag fire was immediate: the fire would be portrayed as the start of a Communist revolution. Not only would Communists, but also Social Democrats and perceived traitors, enemies of the people, be rounded up and made to pay. The very people who stood clearly in the way of the completion of Hitler’s Machtergreifung (rise to power).

Assessing the principle of motive – cui bono (who benefits) – it would seem possible that the Nazis themselves could have been responsible. In some form. Indeed, it has been seriously suggested that a group of SA agitators managed to infiltrate the building and cause the fire – intending to portray the Communist movement as the guilty party.

Journalist William L. Shirer would state openly in his classic work Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, that there was “enough evidence to establish beyond a reasonable doubt that it was the Nazis who planned the arson and carried it out for their own political ends.”

But what evidence?

The official version of events would focus on a young man from Holland by the name of Marinus van der Lubbe – caught inside the building the night of the fire and initially deemed to be the leading actor in this international Communist conspiracy.

His trial, the first major political trial of Nazi Germany, would be an international PR disaster for the Nazi Party – as despite the guilty verdict, it would introduce even more uncertainty into the issue of responsibility for the fire. As van der Lubbe, often appearing unresponsive or incoherent whilst dribbling into his shirt, was exhibited alongside four Communists said to have been involved in the attack.

Reaching its verdict in December 1933, the court could only conclude on van der Lubbe’s guilt. Acquitting the four Communists and leaving more questions than answers as to the real events of February 27th 1933.

Was van der Lubbe guilty? Did he act alone? Was he part of a Communist conspiracy? Or did the Nazis start the fire themselves, blaming the Communists for a violent revolution they themselves were in the process of carrying out?

The historical analysis since has not been without its own controversy – reputations have been built and destroyed on these questions.

Approaching the matter of who could really have been responsible for the Reichstag fire, it would be best to start by looking at the events that sit most firmly in the historical record – what almost universally can be agreed did indeed happen on February 27th 1933.

–

The What And The When Of The Reichstag Fire

“During discussions with the Führer we drew up the plans of battle against the red terror. For the time being, we decided against any direct counter-measures. The Bolshevik rebellion must first of all flare up; only then shall we hit back.”

Nazi Gauleiter for Berlin, Joseph Goebbels, writing in his diary on Jaunary 31st 1933

The wintery temperatures had reached minus 6 degrees – and there had been snow. Leaving the pavements icy and dangerous to walk on. The German parliament, however, was not in session, as it had been dissolved by the Reich President, Paul von Hindeburg, to make way for fresh elections at the start of March.

At 8:45pm, the lighting man would make his rounds, followed some five to ten minutes later by the mailman. As the deputies were away campaigning and the parliamentary staff would clock off by 9pm, that left the building empty until the first inspection by the night watchman, one hour later.

There were, however, police stationed in the vicinity – including a twenty-nine-year-old Chief Constable (Oberwachtmeister) named Karl Buwert, posted to watch the west and north sides of the building for two hours, from 8pm.

His testimony and involvement in the response to the fires would prove to be key in piecing together the events of that cold February night.

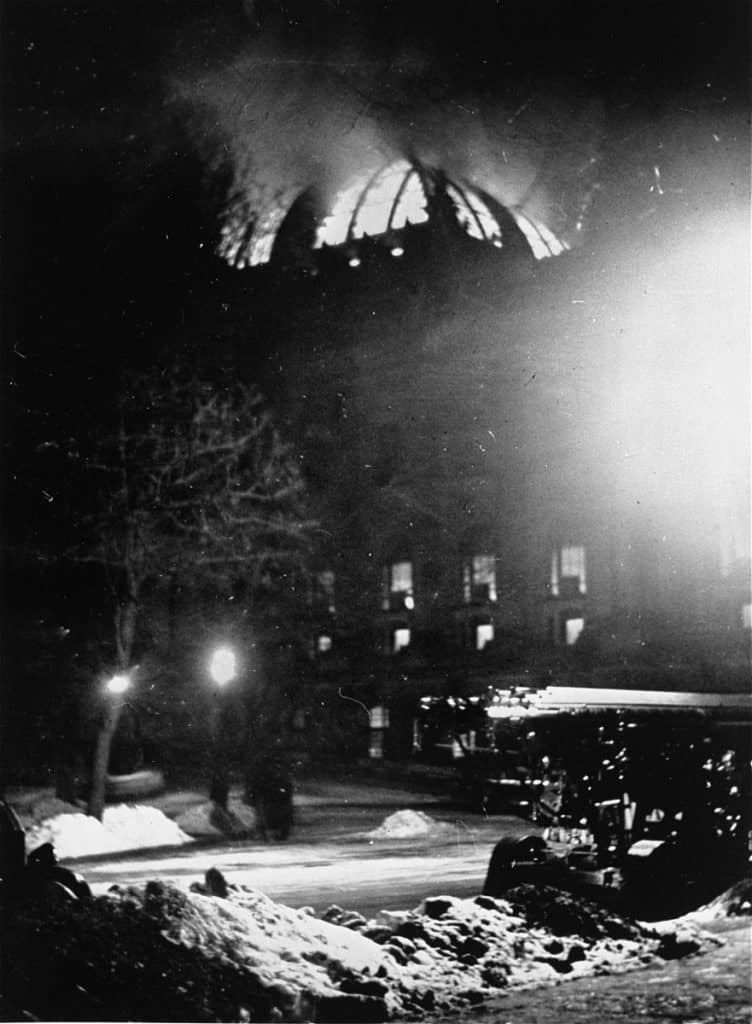

The Reichstag had served as the seat of the country’s lower parliament since its completion in 1894. Designed by architect Paul Wallot, it resembles Memorial Hall in Philadelphia, USA, and sits only a short walk from the Brandenburg Gate, on the northern side of the Tiergarten central park.

The building was severely damaged during the Second World War and subsequently redesigned by British architect Norman Foster, before its grand reopening in 1999. In its original form, it stood as a remarkable neo-baroque masterpiece – that would weather the triumphs and tragedies of the Wilhelmine period and beyond.

Behind its imposing facade, the main plenary chamber of the Reichstag dominated the centre of the building and took up nearly seven thousand feet. Originally designed to provide space for 397 deputies, over time this number had grown to over 600 – with the succession of elections in the crisis ridden Weimar era. To improve the acoustics in the room, wooden panels had been applied to the walls, and although without windows, the chamber was topped with an iron and glass cupola some 246ft in height, that was also meant to provide ventilation.

Aside from this grand main chamber, the building also included kitchens and cleaning rooms, office space for the staff, and even a gymnasium and hairdresser. At the south end of the Reichstag was the parliamentary restaurant, nicknamed “Schulze’s Caucus” after its first owner. There was also a canteen for reporters.

Entrance to the building at this time was possible through five grand portals. The most spectacular being the westward facing Portal I, that was used for ceremonial occasions and provided a panoramic view of the Platz der Republik (Republic Square). Before 1926 and between 1933 and 1948 that area would be known as Königsplatz (King’s Square). The deputies were expected to enter using Portal II, facing south towards the Tiergarten and Brandenburg Gate, on what was then called Simsonstrasse (now Scheidemannstraße), while there were also two other entrances, Portals III and IV, on the east side, and Portal V facing north.

At around 9:05pm, Chief Constable Buwert was approached by a civilian on the steps of Portal I. Theology student, Hans Flöter, was on his way home from an evening at the State Library on Unter den Linden and had heard a window being broken on the front of the building. Looking up, he then saw a man on a balcony in the process of breaking more glass. Flöter rushed to find a police officer in the vicinity and came across Buwert.

Around the same time, a typesetter for the Nazi Party paper, Völkischer Beobachter, named Werner Thaler, also heard the same sounds – while crossing Freidrich-Ebert-Strasse on his was home from work. He would later testify that he was uncertain as to what exactly he saw, but initially claimed to observe two men in the window to the right of the Portal I entrance.

Theology student, Flöter, feeling that his duty had been served continued on his way home; leaving Thaler and Chief Constable Buwert to assess the situation from outside the building. Seeing movement inside, Buwert opened fire in the direction of the suspects, seemingly without hitting anyone.

When at around 9:18pm, the first fire engines arrived, the young typesetter from the Volkischer Beobachter excused himself and headed home. Company 6 from Linienstrasse had received the alarm at 9:14pm and arrived four minutes later.

Buwert was soon joined by Lieutenant Emil Lateit, who was in command of the nearby Brandenburg Gate post that night, and Constables Losigkeit and Graening. The latter chose to immediately return to the Brandenburg Gate post and request reinforcements. He would be replaced by another officer, twenty-two-year-old Hermann Poeschel, who like Buwert had been on patrol outside the Reichstag, and would join the group as they entered the building to assess the scene and search for the culprits.

With Portals II and II locked, the four men managed to enter through Portal V after finding the man responsible for the maintenance of the Reichstag, House Inspector Alexander Scranowitz, who having heard the sirens was already waiting at the entrance with a key.

After gaining access to the building at 9:20pm, the group moved towards the main plenary hall, encountering small fires along the way; including burning curtains, wood paneling, and coats.

At 9:21/9:22pm, Lieutenant Lateit arrived at the main chamber to see flames about ten feet wide and much taller coming from the President’s desk, with the curtains behind and the stenographer’s desk in the process of being engulfed.

The police were quick to conclude this was arson and continued to move through the building with their pistols drawn.

At this point, it appeared a number of culprits had managed to spread fires throughout the interior of the building over the space of around twelve minutes. Planting the fiery seeds of what would grow to become a colossal disaster for German democracy.

–

Uncertain Circumstances

“This is a God-given signal! If this fire, as I believe, turns out to be the handiwork of Communists, then there is nothing that shall stop us now crushing out this murder pest with an iron fist.”

Adolf Hitler speaking to Daily Express correspondent Delmar Sefton – February 28th 1933

As the police officers inside the Reichstag scrambled through the building in search of multiple culprits, they came across the lone figure of a young man, a Dutch citizen from the city of Leyden named Marinus van der Lubbe. He made no attempt to flee and after being confronted by Constable Poeschel on the south hallway heading towards the anteroom of the Reich Council Offices (nicknamed the Bismarck Room) surrendered to be searched and taken into custody.

When the director of the Reichstag, Privy Councilor Reinhold Galle, arrived on the scene, he glanced up at the clock in the corridor outside the plenary chamber and noticed the time – it read exactly 9:25pm – as he saw van der Lubbe being led away.

Ten minutes later, the chief suspect in the Reichstag fire was at the Brandenburg Gate, wrapped in a blanket and waiting to be transported to the police station at Alexanderplatz to be interrogated.

The fires inside the building were still burning. And would continue to do so for another three hours.

When the fire engines from Linienstrasse and Moabit had arrived earlier, they were expecting to combat a fire in the Reichstag restaurant. At the time the flames from the plenary chamber were not yet visible from outside the building.

That would all change for the worst when at around 9:27pm a massive explosion shook the building, as the fires burning in the main chamber combined with the gases that had been generated in this enclosed space.

It would take until just after midnight on February 28th for the blaze inside the Reichstag to be extinguished. With water being drawn from a fireboat in the river Spree and firefighters attacking the building from all sides. The extent of the damage to the building soon became apparent. The main chamber had been almost completely destroyed – with the glass and iron cupola above severely damaged.

Over the space of those three hours, from around 9:15pm until shortly after midnight, as the fires still raged inside the Reichstag, rival narratives were already beginning to circulate.

That of the regime being the first, with a communique issued by Hermann Göring.

The Berlin correspondent for the British Daily Express newspaper, Sefton Delmer, had arrived at the scene by 9:45pm and soon saw two familiar black Mercedes arrive bearing Adolf Hitler and Nazi Gauleiter for Berlin, Joseph Goebbels. President of the Reichstag and future Nazi Airforce Minister, Hermann Göring would soon join the group and brief Hitler on the fire, saying: “Without a doubt this is the work of the Communists, Herr Chancellor.”

Later, while touring the building with Hitler, Delmer was directly addressed:

“God grant that this be the work of the Communists. You are witnessing the beginning of a great new epoch in German history, Herr Delmer. This fire is just beginning.”

Shortly before midnight, however, a reporter for the Wiener Allgemeine Zeitung sent a telegram to his editor that suggested another narrative:

“There can be little doubt that the fire which is consuming the Reichstag was the work of hirelings of the Hitler government. It seems that the incendiaries have made their way to the Reichstag through an underground passage which connects the building with the palace of the Reichstag President.”

Nothing to do with the Reichstag fire would be exactly as it seemed.

Word of the fire reached the thirty-two-year-old commander of the political department of the Berlin police, Rudolf Diels, whilst he was on a date at the Café Kranzler on Unter den Linden. He had rushed to the parliament and managed to arrive a few minutes before Hitler and Goebbels.

Göring and Hitler would both express to Diels their certainty that a Communist attempt at revolution was underway. Diels would later recount that Hitler unleashed one of his trademark monologues whilst the fires were still burning:

“There will be no mercy now. Anyone who stands in our way will be cut down. The German people will tolerate no leniency. Every Communist official will be shot where he is found. The Communist deputies must be hanged this very night. Everybody in league with the Communists must be arrested. There will no longer be any leniency for the Social Democrats either.”

The response from those in power was immediate. This was the ultimate opportunity to strip the democratic Weimar system of its legitimacy and finally eliminate any opposition that stood in the way of a complete takeover by Hitler’s Nazi Party.

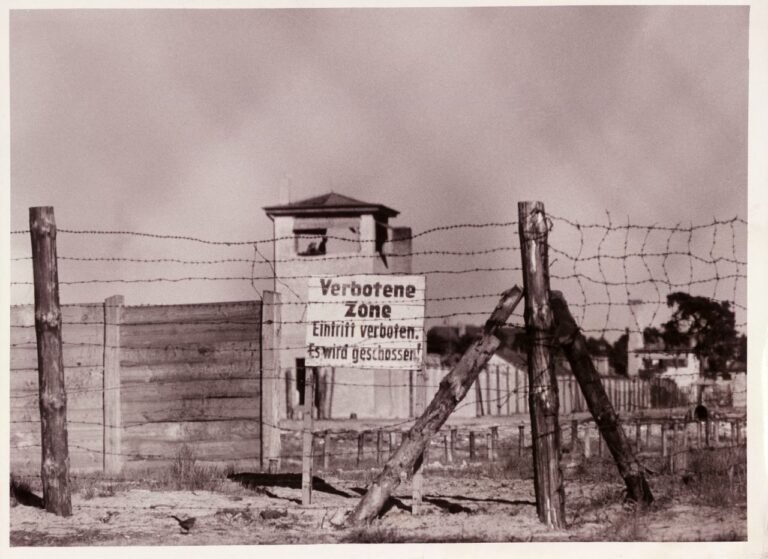

The Reichstag fire would thus not only come to be the death knell of the Weimar Republic, signalling the downfall of German democracy, but also the “birth hour of the concentration camps”.

The Berlin Sturmabteilung (SA) had been compiling lists of enemies for years; and on the night of the fire would begin rounding up these opponents – dragging them into SA headquarters, improvised torture facilities, abandoned warehouses and brewery complexes. The era of the ‘wild concentration camps’ had begun.

By the time Rudolf Diels arrived back at the Alexanderplatz Berlin police headquarters, he could already see the result of the official action against the ‘traitors’ that Göring and Hitler had both railed against.

Marinus van der Lubbe was already under arrest, soon to be joined by three Bulgarian Communists on March 9th 1933, who would be charged with complicity in the Reichstag fire. A further German Communist, Ernst Torgler, the head of the KPD faction in the parliament surrendered to the authorities on February 28th, following the issuing of an arrest warrant, he would also appear alongside the three Bulgarians and Van der Lubbe in the first major political trial of Nazi Germany, that took place from September to December 1933, at the supreme criminal court in Leipzig.

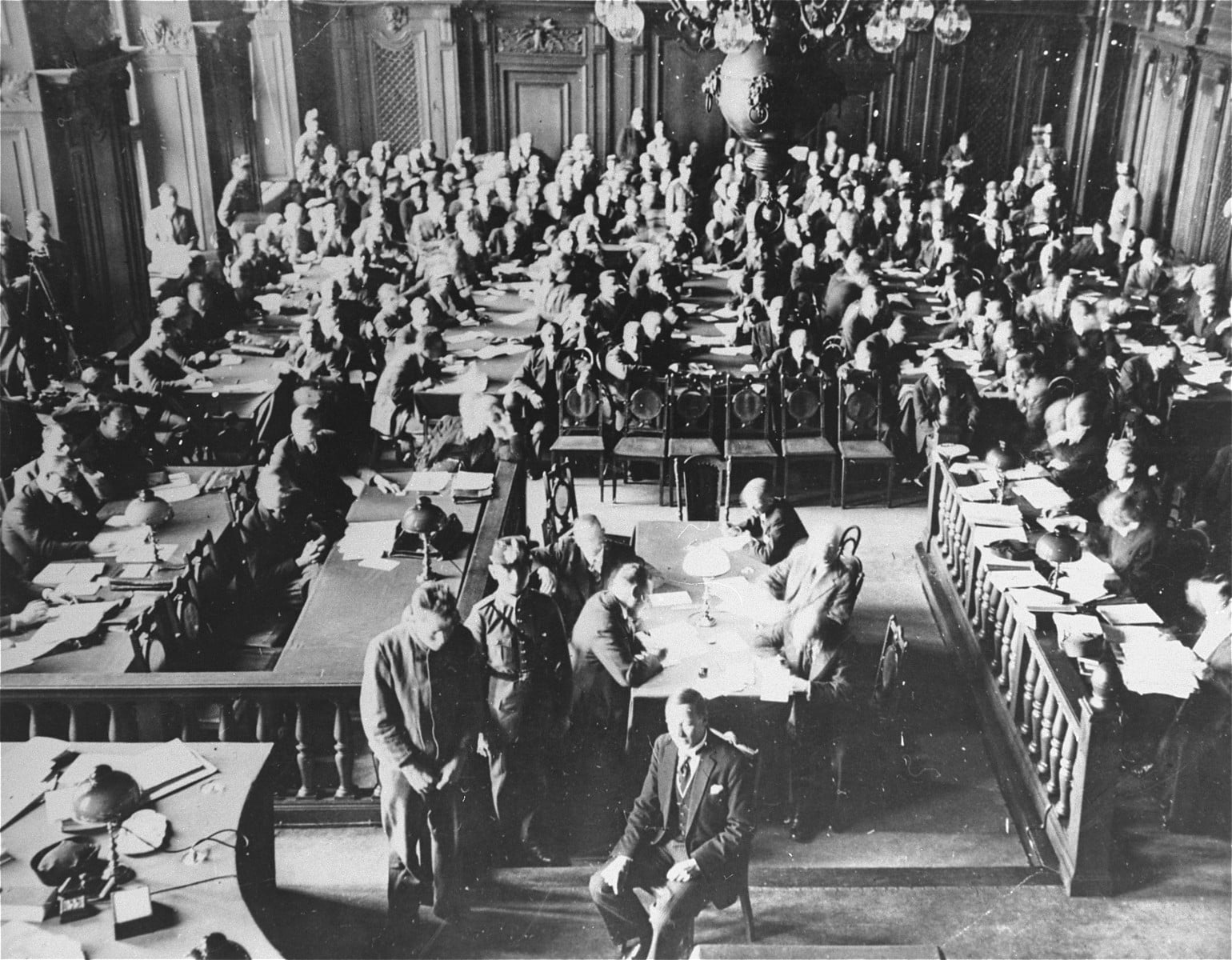

Commonly known as the ‘Leipzig Trial’.

–

The Reichstag Fire Trial - Communism In The Dock

“I myself am a Leftist, and was a member of the Communist Party until 1929. I had heard that a Communist demonstration was disbanded by the leaders on the approach of the police. In my opinion something absolutely had to be done in protest against this system. Since the workers would do nothing, I had to do something myself. I considered arson a suitable method. I did not wish to harm private people but something belonging to the system itself. I decided on the Reichstag. As to the question of whether I acted alone, I declare emphatically that this was the case.”

Marinus van der Lubbe’s police statement – March 3rd 1933

Although much of the evidence brought to implicate von der Lubbe by the police would prove ridiculous or blatantly fabricated, the trial came to the kind of conclusion which the regime was hoping for; albeit minus one detail.

In the process against van der Lubbe, the notion that he had acted as part of a criminal conspiracy alongside his Communist party allies had to be abandoned. Even a court leaning so cleary towards the Nazi Party line could not convict the four other defendants, and had to conclude the van der Lubbe had in-fact acted, somewhat, alone. A point that he himself made numerous times throughout the trial. Although the final statements did indicate that the court suspected additional culprits who at the time remained unknown.

This theatrical performance took three months to play out, starting on September 21st with Van der Lubbe himself testifying as to his background and Communist Party membership.

He had actually left the Communist Party in 1931 – but claimed to still consider himself part of the movement. Beyond the evidence that clearly placed him at the scene of the crime (as he was arrested inside the building during the fire), van der Lubbe also had a record of unsuccessfully attempting to set fire to public buildings in protest against the political and social system he held responsible for mass unemployment.

However – falsified interrogation transcripts, witnesses brought directly from concentration camps and forced to stand rigidly at attention whilst giving evidence, and a Berlin guidebook that police claimed as evidence of a coordinated attack – all drew the case towards the absurd.

Marinus van der Lubbe’s appearance during the trial has also been the subject of much attention since – as it was during the proceedings. German historians Alexander Bahar and Wilfried Kugel have argued that the Dutchman’s behaviour at the trial was consistent with the symptoms of excessive ingestion of potassium bromide – commonly known as Cabromal – a popular sedative used at the time. It is possible that van der Lubbe, who was observed receiving separate food parcels throughout the trial marked with his name, was being intentionally poisoned – leading to his slumped body posture, mental slowness, loss of memory, and constantly running nose. Potassium bromide would be hard to detect in the food parcels as its flavour could easily be confused with that of salt.

Had Van der Lubbe been poisoned to keep him docile and unable to implicate anyone else who might have been involved – Nazi or Communist?

On November 4th, Hermann Göring appeared at the trial as a witness, testifying over the space of three hours in a way that did more to address his disappointment in the circumstances rather than provide any useful elaboration of his potential role. It is almost certain that Göring had been prepared for his appearance by Gestapo chief, Rudolf Diels.

Exclaiming that he had nothing to do with the Reichstag fire, Göring instead used the opportunity to attack the Communists, saying he had moved against the Communists immediately after the fire due to public sentiment.

“I was like a general who had planned a big attack and was forced through the action of the enemy to change his plans.” He had known of the planned Communist insurrection but wanted to “await this occasion to destroy them in one blow”.

The fire had only served to expedite the process.

Explaining van der Lubbe’s involvement and the potential of additional culprits, Göring said: “When I saw the face of this idiot, everything was clear to me… The others knew their way around in the Reichstag but that guy there never found the exit.”

To Göring, van der Lubbe was merely a decoy.

Examined by Communist defendant Georgi Dimitrov, Hermann Göring famously lost his cool, in an exchange that exposed to the world the bias with which the regime had approached the question of responsibility for the Reichstag fire.

Dimitrov inquired how could Göring have known already on the night of the fire that the Communists were guilty – suggesting that by reaching such a conclusion that he had given a “definite direction” to the police and “closed off” the “possibility of finding other paths and the true Reichstag arsonists”.

“Listen, I will tell you what the German people know,” Göring replied, “The German people know you are conducting yourself shamelessly, that you have come over here, set the Reichstag on fire, and then still indulge in such insolence with the German people. I didn’t come here to let myself be accused by you… In my eyes you are a crook who should have been hanged a long time ago.”

Dimitrov pursued the matter, saying: “Are these questions making you nervous, Herr Prime Minister?”

To which Göring yelled: “You’ll be nervous when I get you, when you are out of this court, you crook.” His face a deep purple colour as his words bellowed across the courtroom.

Rather than reprimanding the Prime Minister of Prussia, the court expelled Georgi Dimitrov from the proceedings for three days. The damage, however, was already done. Göring’s behavior would turn out to be a public relations disaster for the government, as the international reporters in the room recoiled at his belligerence and cast his threats as mafia tactics of the kind more suitable to the likes of Al Capone than a minster of one of the world’s major states.

After three months, the trial in Leipzig finally reached its conclusion – the Fourth Senate of the Reich Supreme Court acquitted Georgi Dimitrov, along with fellow Bulgarian Communists Vasil Tanev, Blagoy Popov, and reached a similar verdict with Ernst Torgler.

On February 27th 1934 – one year exactly after the Reichstag fire – the three Bulgarians were released on Hitler’s orders and flown to the Soviet Union where Dimitrov would rise to lead the Comintern with the mission of establishing a ‘Popular Front’ for the political left across Europe. After spending the war in Moscow, he would become the first Communist leader of Bulgaria.

Van der Lubbe was found guilty on several counts of treason, “seditious arson”, and attempted simple arson.

Although convinced that van der Lubbe was responsible for some of the fires inside the Reichstag that evening, the court found that he could not have started the fire inside the plenary chamber, which must have been “prepared by another hand” with “large quantities” of kerosene or gasoline. At least one or “probably several” accomplices had been responsible for the fire, although none were named.

Importantly, the court did not believe that van der Lubbe had even set foot in the plenary chamber at all – and therefore could not have been responsible for the main fire.

The Dutchman’s real role had been to divert attention away from the real culprits – assumed to be Communists – and after his capture he had remained silent as to who these co-conspirators actually were.

Refuting the idea that the accomplices had been Nazis, the court found that the tunnel to the Reich President’s residence had not been the escape route used.

Regardless of the extent of his involvement, van der Lubbe was sentenced to death for his actions. Even though none of the charges he was convicted of carried the death penalty on February 27th 1933. The principle of criminal law in Germany was such that a court cannot legally apply criminal punishments retroactively. Despite this, Hitler’s government had passed a special law on March 29th (dubbed ‘Van der Lubbe’s law’), extending the death penalty provisions introduced by the earlier Reichstag Fire Decree to acts committed between January 31st and February 28th.

On Wednesday, January 10th 1934, at 7:28am Marinus van der Lubbe was led into the courtyard of the remand prison in Leipzig and in less than a minute met his end. Chief Reich Prosecutor, Werner, read the formal announcement of his sentence:

“The mason Marinus van der Lubbe from Leyden, Holland, has been sentenced to death for high treason in combination with seditious arson and attempted arson…” He concluded: “I give the mason Marinus van der Lubbe to the executioner for the execution of the death sentence. Executioner, do your office.”

The protocol recorded that at exactly 7:28:55am, Marinus van der Lubbe was executed by guillotine.

The controversy surrounding the Reichstag fire, however, would certainly not end with his death.

–

The Question of Co-Conspirators

“People outside Germany, and many inside it, found a simple answer: the Nazis did it themselves. This version has been generally accepted. It appears in most textbooks. The most reputable historians, such as Alan Bullock, repeat it. I myself accepted it unquestioningly, without looking at the evidence.”

British historian A.J.P. Taylor

To question the established fact of Communist guilt in regards to the Reichstag fire was incredibly dangerous in Nazi Germany. It was possible to be charged with treachery (Heimtücke) if overheard suggesting that the Nazis had started the fire themselves.

Outside the country, however, there was considerable doubt that the fire had been the result of a sole perpetrator or that if Van der Lubbe had in-fact had accomplices that they were of the Communist persuasion.

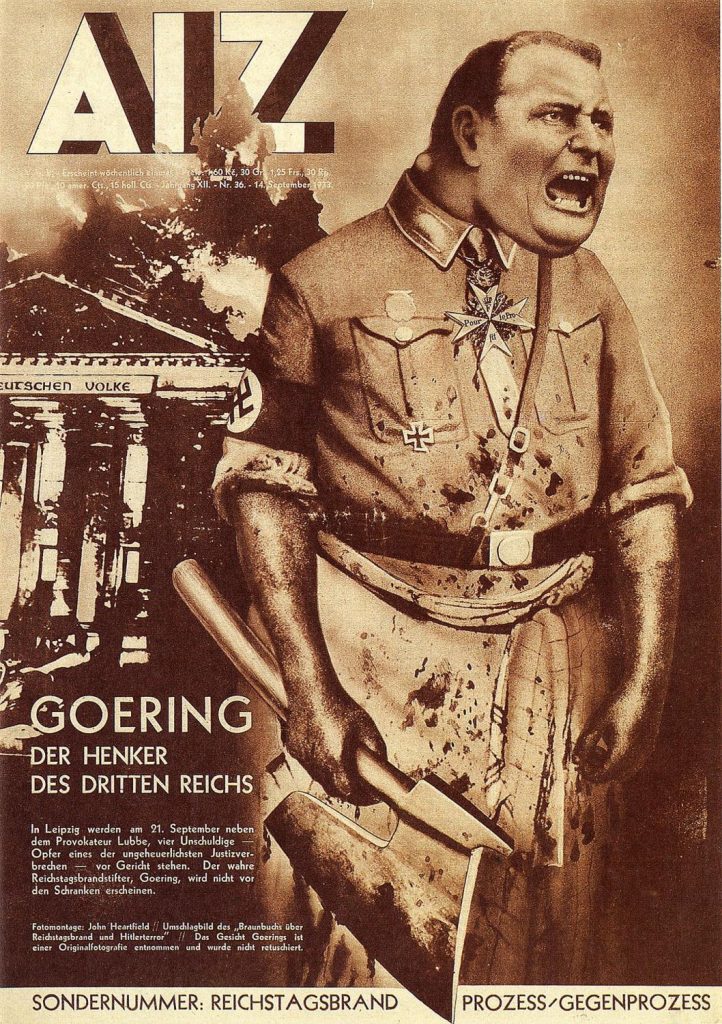

The international perception of what had actually transpired would be as much a result of the ham-handed staging of the Reichstag fire trial as the response from Communist circles – with notable media entrepreneur Willi Münzenberg, the Communist activist behind a series of publications portraying the fire as the symbolic opening act of Nazi state criminality, largely responsible for this view.

Münzenberg’s first “Brown Book on Reichstag Fire and Hitler Terror” was published in the summer of 1933 – one of three publications that would focus on highlighting the Nazi’s brutal and conspiratorial actions – and succeeded in shaping world opinion outside Germany. Although only a small section of the publication actually dealt with the Reichstag fire; instead focusing on the Nazis rise to power and the reasons (unsurprisingly this would serve as a heavy critique of the Social Democrats). Author Artur Koestler would famously describe the Brown Book as: “the Bible of the anti fascist struggle”.

The central thesis proposed regarding the fire is that it could not have been the work of Van der Lubbe alone – instead it was surmised that an SA squad had entered the building through a tunnel connecting the parliament to Hermann Göring’s residence and staged the attack with the intention of blaming the Communists.

The book went even further: claiming that Marinus van der Lubbe was gay. Introducing the possible connection to Nazi Sturmabteilung leader, Ernst Röhm, himself a known homosexual.

Münzeberg had decided to organise a counter-trial in September 1933, lasting one week and exposing the real culprits – although successful as a publicity stunt this somehow managed to come off more as a show trial than the real proceedings taking place in Nazi Germany.

When Communists defendant Ernst Torgler was acquitted at the counter-trial due to exonerating evidence, his lawyer at the actual trial tried to convince Münzenberg to provide this material – only to be told that it does not exist.

Guilt in London would be assigned to Herman Göring and the Nazi elite, as well as a group of Sturmabteilung men, among them Edmund Heines and Berlin SA leader Karl Ernst.

Certainly there were some unusual occurrences the night of the fire inside the Reichstag that could indicate foul play.

One of the more peculiar details to emerge from the reaction to the Reichstag fire on the ground, was the account of twenty-six-year-old fireman Fritz Polchow, assigned to Company 6 on Linienstrasse.

Polchow had arrived, with his company under the command of Senior Fire Chief Emil Puhle, at around 9:18pm. The team set up a ladder to the window of the Reichstag restaurant and broke one of the windows with an axe. While Fire Chief Puhle set to work putting out the small fires they encountered, Polchow was sent further into the building to investigate.

Four days after the fire, he would give a statement to the Berlin police (received by Commissar Bunge) of what happened next.

Finding a staircase behind a counter, Polchow went down it to a door and “ran into police officers coming towards me from below.” The passage of Polchow’s statement is heavily underlined in the prosecutors copy of the Reichstag fire evidence.

Polchow would later expand on the story in 1955, when as second in command of the West Berlin fire brigade, he discussed the particulars with Reichstag fire researcher Richard Wolff, saying at the bottom of the stairs he was: “confronted by several pistol barrels that were being held by persons in brand new police uniforms.”

Having reached the Reichstag at 9:18pm, before breaking into the building, it took around five minutes for company 6 to get into the restaurant, at which point Polchow was dispatched to explore further. This would suggest that Polchow was on the stairs at around 9:23-9:25pm.

At this point in time, there could have only been one police officer in the cellar space, Constable Losigkeit, having been sent by his superior Inspector Scranowitz in search of arsonists.

That begs the question: who were these police officers, armed, and wearing new uniforms? And what were they doing in the cellar? Could they have been the SA men suspected of using the tunnel underneath the building to gain access and start the fires?

Several days of testimony at the trial in October were dedicated to exploring the tunnel entrance to the building and the possibility of its use by multiple culprits. This underground passageway connected the cellar of the Reichstag with the President’s residence and the boiler house, a result of architect Paul Wallot’s intention to keep the boilers away from the main building in case of fire.

Testifying at the trial, master machinist Eugen Mutzka explained that the tunnel could be opened with the Reichstag master key, as there were locks on the Reichstag cellar and the boiler house doors. Anyone in possession of such a key could use the tunnel to escape from the building and over the boiler house wall.

On October 17th, the Leipzig court treated the press to a tour of the tunnel. The result being a general agreement amongst the reporters that it was possible for any responsible party to use the tunnel as an escape.

In-fact, the night porter at the President’s residence who had been on duty the night of the fire, although reporting nothing unusual that evening did testify to having heard people moving through the tunnel multiple times in the weeks preceding the fire. The kind of activity that was considered so suspect by the House Inspector and Reichstag Director, that the night porter decided to place thin strips of paper across the tunnel doors at night, and wood chips on the floor to better register any disturbances.

The same porter would discover these paper strips torn “about six times”.

It would seem clear that someone besides the Reichstag employees was in possession of a key.

Both SA men mentioned in the Reichstag counter-trial as being suspected of involvement with the Reichstag fire met their end on the same day in 1934 – June 30th – commonly known as the Night of the Long Knives. As members of the Sturmabteilung, they were executed to alleviate concerns the German Army had with the growing power of the SA, and increase Adolf Hitler’s personal power, although in a speech to the parliament on July 13th 1934 Hitler would express his approvement of these extrajudicial killings as the men were part of a: “small group of elements which were held together through a like disposition”.

It is widely believed that Hitler was referring to the homosexual orientation of some of the men executed that night. But was there another disposition which had brought these men together – that of a group tasked with doing the dirty work of a political party attempting to foment strife, so that it could then pose as the solution to the problems it was in-fact directly responsible for?

The Reichstag fire issue would be surpassed by greater problems that would arrive with the growing brutality and criminality of the Nazi regime in the late 1930s and 1940s.

However, with the end of the Second World War in 1945, new evidence would come to light, fresh eyes would be tasked with examining archives, and testimonials from some of the individuals involved would generate renewed interest in the question of what really happened on that cold February night.

–

The Post War Perspectives - Spies, Lies, & Questionable Ties

“From the night of the fire to this day, I have been convinced that the Reichstag was set on fire neither by the communists nor Herman Göring, but that the fire was the piece de resistance of Dr. Goebbels’s election campaign, and that it was started by an handful of Storm Troopers all of whom were shot afterwards by SS commandoes in the vicinity of Berlin. There was talk of ten men, and of the Gestapo investigating the crime.”

Martin Sommerfeldt – Herman Göring’s Press Chief writing is his memoirs ‘I Was There’ (1949)

Perception of the events surrounding the Reichstag fire have changed over time; certainly directly after the end of the Second World War there was a renewed interest in further examination of the circumstances, the verdict of Van der Lubbe’s sole responsibility, and the possibility of conspiracy.

By the mid-1960s, one name had become prominent in the search – that of Fritz Tobias. A senior official of the Office for the Protection of the Constitution in the West German federal state of Lower Saxony, who by his own account would spend his spare time researching the events of February 27th 1933.

Tobias initially published his findings in a series of articles for the West German magazine Der Spiegel before releasing a lengthy book dedicated to the Reichstag fire in 1962.

The conclusion: Van der Lubbe had in-fact acted as the sole perpetrator and no evidence of Nazi involvement was forthcoming.

To Tobias’ critics, his work was further evidence of a cover-up by Nazi sympathisers eager to protect the culprits from prosecution. This was after all, the era of a New Germany, cast in the long shadow of war crimes, denazification, and Persil papers. Anti-communism would be the vehicle for integrating old Nazis into the new democracy as it had been for integrating right wing non-Nazis into the Nazi system. It would be no great leap for this prejudice – or willingness to turn a blind eye to alternatives – to extend into the academic world at the time.

Contemporary researchers like Benjamin Carter Hett contend that Tobias’s modus operandi in carrying out his research was suspect as he made use of agents from the Office for Constitutional Protection to threaten academic historians who disagreed with his arguments. With Hett claiming that Tobias even went as far as blackmailing the director of the Munich-based Institut für Zeitgeschichte, Helmut Krausnick, with classified documents that would reveal his Nazi past unless he endorse Tobias’ work.

Criticisms of his work aside, Tobias did manage to successfully challenge many of the conclusions made in the much-flawed Brown Book, including that SA leader Karl Ernst had been directly involved – when it could be proven that he was in-fact at an election meeting faraway in Gleiwitz.

Arguing that the mere fact that Van der Lubbe was allowed to stand trial in the first place illustrated the lack of Nazi involvement, Tobias would state:

“Today there seems little doubt that it was precisely by allowing van der Lubbe to stand trial that the Nazis proved their innocence of the Reichstag fire. For had van der Lubbe been associated with them in any way, the Nazis would have shot him the moment he had done their dirty work.”

Certainly the Nazis were not beyond eliminating enemies or those no longer useful to them. But at a time when the Party was trying to consolidate control in the country and present this new Germany as a genuine world class power, paying lip service to legality and the rule of law by holding a trial and appearing constitutional would not run contrary to this line.

Especially if there is any truth to the claim that Van der Lubbe was in a sedated state for the majority of the trial – and thus effectively ‘neutralised’.

Tobias’ main resource for his work was Walter Zirpins, a German lawyer and police officer who had been one of the main investigators in the Reichstag fire case and testified at the trial. He would later rise within the ranks of the SS and head the criminal police in the Litzmannstadt ghetto. After the war he would feature on the Polish government’s list of war criminals for his participation in the killing of Jews in the Litzmannstadt ghetto.

In 1951, Zirpins was hired alongside Fritz Tobias at the Lower Saxon Interior Ministry, before moving to the more prestigious position of Chief of the Criminal Police in Hanover in 1956.

Concluding his official report in March 1933, Zirpins had stated:

“The question of whether van der Lubbe carried out the act alone should be answered in the affirmative without hesitation…(although) the question of whether the extensive fire in the plenary chamber in particular could have started so quickly in the manner described [by van der Lubbe] should still have to be examined by experts.”

The sole-culprit theory endorsed by Tobias – while not without its supporters – has also been suggested to be a mis-representation at best, at worst the evidence of something more sinister.

The question of whether Tobias’s thesis affirming van der Lubbe’s sole guilt was presented as a way of serving the interests of the people in power in West Germany at the time – allowing many old names to remain unmolested in their civil service especially – or in-fact perhaps even an official assignment commissioned to attack advocates of the Nazi responsibility for the fire, remains disputed amongst historians to this day.

Certainly when asked in court to reveal details of his research and methods, Tobias chose to fall back on his official cover, declining to answer due to his duty to maintain official secrets.

One of the most important opponents of the single-culprit theory was German diplomat and intelligence officer, Hans Gisevius, who in 1946 published his autobiography, entitled To The Bitter End, detailing his involvement with the German resistance and offering a unique insider account and indictment of the Nazi regime.

Gisevius, who was no stranger to Nazi tactics – having served in the Gestapo in 1933 before transferring to the Abwehr military intelligence service – claimed that the Reichstag fire had been the work of an SA detachment, organised by Gruppenführer, Karl Ernst, and including SA man, Hans Georgi ‘Heini’ Gewehr. The death of a stormtrooper named Adolf Rall, who was murdered in November 1933, was cited as further evidence of a conspiracy, as Rall had reportedly confessed to involvement in the plot – having been tasked by Ernst with infiltrating the parliament through the tunnel and starting the fires.

Rall’s confession was overheard by a fellow stormtrooper whilst Rall was detained in prison for car theft, his naked body would be discovered in the woods near Strausberg, north of Berlin. Official records would indicate he had escaped from custody.

The mysterious circumstances of Rall’s death were reported in December 1933 by the German language exile newspaper Pariser Tageblatt – stating that a “man who knew too much” had been eliminated.

Of course, even if Rall met his end at the hands of the Sturmabteilung, this would be no indication of Nazi guilt when it came to the question of the Reichstag fire. As Fritz Tobias rightly pointed out, even if his account was false, his confession would have been an embarrassment for the SA, given them a suitable reason to silence him.

Some of the details of Gisevius’s research would prove laughably incorrect – including that Adolf Rall had been in prison since 1932 and could not have been personally involved with the Reichstag fire. Although that would not prove his account of the conspiracy incorrect, nor prove enough justification for Fritz Tobias’ dismissal of Gisevius as a “pathological liar”.

As a result of Hans Gisevius’s book, the former head of the Gestapo, Rudolf Diels, chose to make a statement to the British Delegation at the International Military Tribunal regarding his opinion on the real perpetrators of the fire, headed “Re: Reichstag Fire 1933”:

“As I have been informed by the defense counsel for the SA, the former SA leader Heini Gewehr, who in Gisevius’s book To the Bitter End is identified as the chief culprit in the burning of the Reichstag and is also held by me to be so…”

In 1983, Rudolf Diels personal papers were turned over to the State Archives of Lower Saxony by his former mistress, where the document resurfaced – although the papers were to remain closed to the public until 1994, there were two exceptions. That Fritz Tobias would be allowed access – and also a man named Adolf von Thadden, a founding member of the neo-Nazi NPD party.

Historian Benjamin Carter Hett importantly notes that Fritz Tobias: “never cited this document in any of his writings, even his later ones.”

By the 1970s, an important new figure had entered the popular discourse of Reichstag fire analysis – another amateur historian. Croatian born Edouard Calic was a correspondent for a Zagreb newspaper in 1940s Berlin when he was arrested and spent three years in the Sachsenhausen concentration camp. He would emerge after the war as one of the founders of the International Committee for Scholarly Research on the Causes and Consequences of the Second World War – also known as the Luxembourg Committee. Another critic of Fritz Tobias’s single culprit theory, Calic would see the publication of a volume of “Scholarly Documentation” concerning the Reichstag fire in 1972, including important thermodynamic analysis of the fire proving that van der Lubbe could not have been solely responsible, armed only with the accelerants that he described.

Calic would be the subject of a smear campaign and flurry of allegations, much orchestrated by Fritz Tobias, with the intention of discrediting his work. Indeed, it would emerge that Calic was relying on forged documents for many of his findings, and that many of the documents used by the Luxembourg Committee did not exist in their original form.

The findings of the first Committee publication in 1972, however, had delivered a persuasive critique of the single-culprit theory, only the rebuttal would be obscured by the scandal surrounding the later actions of the Committee.

Today there are many historians who still remain convinced of the single perpetrator theory – and that Van der Lubbe acted alone – despite what evidence has been introduced since. British historian, Richard J Evans, notably pointing to how despite endless hours of interrogation, van der Lubbe never deviated from his story that he had acted alone, and never once accused the Nazis themselves of being behind the crime.

More extreme answers have been proposed, you might even stumble across fringe theories, such as that the fire was set by Shell Oil, if you look in the wrong places.

As Benjamin Carter Hett concludes in his book ‘Burning The Reichstag’:

“The notion that Van der Lubbe was the sole culprit in the Reichstag fire first arose (apart from in the unclear mind of Van der Lubbe himself) as a fall-back position devised by elements in the Nazi regime, as it became clear that the Reichstag fire trial was going badly and they were losing the propaganda battle.”

It would later be revised, post-war, as a defence and rehabilitation strategy for ex-Gestapo officers:

“These officers had brought van der Lubbe to the guillotine, and Torgler and the Bulgarians within a hair of it, through an investigation relying on both faked evidence and absurdly improbable witness testimony. Then went on to commit serious crimes in connection with the Nazi Holocaust.”

Strangely, recently unearthed information has done little to alter the general perception of who was really responsible for the Reichstag fire. Although the availability of new archive documents following the collapse of East Germany and the Soviet Union has meant that historians now have access to additional material related to the event: some of which further indicates the involvement of responsible parties beyond van der Lubbe.

In July 2019, the Hannoversche Allgemeine Zeitung published a 1955 affidavit from a former member of the Nazi Sturmabteilung named Hans-Martin Lennings, found in the archives of the Hannover Amtsgericht. In the document, Lennings states that on the night of the fire he was with an SA group that drove van der Lubbe to the Reichstag where they observed the “strange smell of burning” and “clouds of smoke billowing through the rooms”. Suggesting that the building was already on fire when van der Lubbe was deposited inside and left as a decoy. Later, nearly all of those with knowledge of the fire had been executed, while Lennings managed to escape to Czechoslovakia.

While the discovery of another document with testimony that further complicates the picture of who was really responsible for the Reichstag fire does not clearly indicate any definite answer, it certainly serves as a reminder of one important aspect of this story: that there may very well be more documents out there waiting to be unearthed, and that the smoke and mirrors of the events of February 27th 1933 may one day be answered with clarity and finality.

**

Conclusion

Still Inconclusive

It would appear that the verdict remains uncertain.

Undeniably, Marinus van der Lubbe was involved, although it would appear not responsible for the main fire inside the building. While no traces of kerosene or other incendiary liquids were found at the scene of the blaze; experts, even those consulted in 1933 by the Supreme Court in Leipzig, have consistently claimed that it would have been impossible for one person to have managed to start the fires inside the Reichstag on February 27th without accelerants.

And that it would have been an incredible feat for Marinus van der Lubbe alone to cause the extent of damage to the building in the 13 minutes that the attack took place.

The direct and circumstantial evidence does point towards the likelihood of multiple persons involved, rather than a single culprit. Although the real perpetrators appear lost to history – for now at least.

It is undeniable that many officials in the Nazi regime acted, in a coordinated way, to obscure the more secret actions of the state and even undesirable details of everyday life. The Nazis remain suspect. The Communists less so.

But wishful thinking in assuming the real culprits, as ever, makes for poor detective work.

***

HISTORICAL ARTICLES

Mythbusting Berlin

Did Any Of The Rothschild Dynasty Die In The Holocaust? – Mythbusting Berlin

The Rothschild name is synonymous with immense wealth, influence, and persistent conspiracy theories—especially during the era of Nazi Germany. Often targeted by antisemitic propaganda, the family’s survival during World War II has sparked myths about their supposed immunity from Nazi persecution. But did any Rothschild family member actually perish in the Holocaust? This article explores that compelling question, unraveling historical misconceptions and revealing the reality behind one of Europe’s most famous dynasties.

Did Frederick The Great Introduce The Potato To Germany? – Mythbusting Berlin

One of the more bizarre claims to fame attributed to the first King of Prussia is that the man who would go down in history known as Frederick the Great introduced the potato to Germany during his reign back in the 1700s. This starchy root vegetable has undoubtedly become a staple part of German cuisine – an essential addition to any plate of Schnitzel, Schweinshaxn, and Königsberger Klopse – however, whether Frederick the Great is

Did Hitler Escape To Argentina In 1945? – Mythbusting Berlin

Although Nazi leader, Adolf Hitler, certainly remains an inescapable figure, could there be any truth to the story of his escape to Argentina in 1945? That the most wanted man on earth could simply vanish, to spend the rest of his life peacefully in South American obscurity captivates imaginations. Yet, despite numerous investigations, this tale persists primarily as myth—fueled by speculation, hearsay, and conspiracy theories.

Did The Nazis Invent Decaf Coffee? – Mythbusting Berlin

Persistent rumors claim that Nazis preferred their coffee anything but pure, leading some to wonder if they might have influenced the development of decaffeinated coffee. Although decaf was already widely available across Europe by the mid-20th century, speculation continues: could the Nazis really have played a role in popularizing—or even discovering—this caffeine-free alternative, or is this simply another caffeinated conspiracy cooked up to sensationalize an ordinary historical detail?

Did The Nazis Invent The Bicycle Reflector? – Mythbusting Berlin

The fruits of wartime ingenuity are plenty – so many, in-fact, that it has become somewhat of a worn cliche that as the guns start firing the innovators get to work, often solving problems while providing more problems for the enemy to overcome.The kind of progress that results in the production of newer improved, more lethal weapons, such as to increase the chances of victory.

Did The Nazis Run The Largest Counterfeiting Operation In History – Mythbusting Berlin

During the Second World War the Nazis masterminded an astonishing plot to destabilise Britain by flooding its economy with counterfeit banknotes. Crafted in secret by concentration camp prisoners, this forged fortune became the most ambitious counterfeiting operation ever attempted. But was it history’s largest? Dive into the extraordinary tale of Operation Bernhard,

rife with deception, survival, and intrigue—revealing the truth behind one of the Third Reich’s most audacious schemes and its surprising legacy.

Did The Spanish Flu Pandemic Help The Nazis Take Power? – Mythbusting Berlin

The devastating Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918-1919 struck amid Germany’s post-war turmoil, compounding social instability, economic hardship, and widespread political disillusionment. Could this catastrophic health crisis have indirectly paved the way for Nazi ascension? While often overshadowed by war and revolution, the pandemic’s profound psychological and societal impacts arguably contributed to the perfect storm, enabling extremist ideologies—including Nazism—to gain popularity and ultimately seize power in a fractured Germany.

Was Adolf Hitler A Drug Addict? – Mythbusting Berlin

Solving the enigma of the ‘Führer’ has become a preoccupation for many, since the arrival of the Austrian-German onto the world stage – although moving beyond the mythology without falling into the trap of prejudically extrapolating on the psychopathography of Hitler or demonising so as to excuse his actions has proven problematic. What to make of the man who became more than the sum of his masks? The painter; the military dilettante, the mass murderer,

Was Currywurst Invented In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

Explore the story behind what many consider Berlin’s most iconic snack—the ever-so-humble Currywurst. Often hailed as an enduring symbol of culinary creativity amid Cold War scarcity, this humble dish has inspired fierce debate about its true origin. But was it genuinely invented here in Berlin, or have proud locals simply adopted and elevated this spicy street-food favorite into legendary status all their own?

Was Frederick The Great Gay? – Mythbusting Berlin

Frederick II of Prussia, better known as Frederick the Great, is often remembered as the archetypal enlightened monarch – a brilliant military commander, patron of the arts, and learned philosopher. Yet behind the stern portraits of this 18th-century warrior-king lies a personal life long shrouded in intrigue and speculation. Intrigue around the king’s sexual orientation has persisted through the centuries, chiefly revolving around one question: Was Frederick the Great gay?

Was The Colour Blue Invented In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

Tracing the true history of blue—from ancient Egyptian dyes to the accidental discovery of Prussian Blue in a Berlin lab. We’ll debunk myths about seeing blue, explore colonial indigo plantations, scale mountains with a cyanometer, and trace Van Gogh’s starry skies—all to answer one question: how did Berlin shape our understanding of the world’s rarest color?

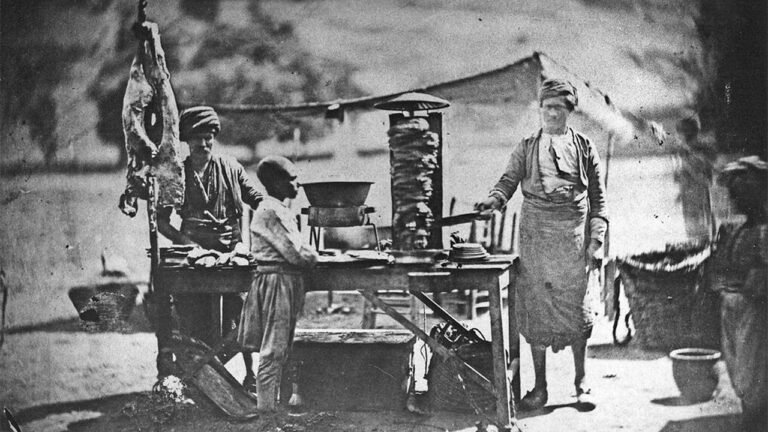

Was The Döner Kebab Invented In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

Unlikely icon of immigrant success; fast food symbol of the working class; over-hyped midnight disco eat; or culturally appropriated cuisine? Its influence goes far beyond layers of seasoned meat and fresh vegetables stuffed into pita bread. But does Berlin deserve credit as the Döner Kebab’s true birthplace, or has the city merely refined and popularized a culinary tradition imported from elsewhere?

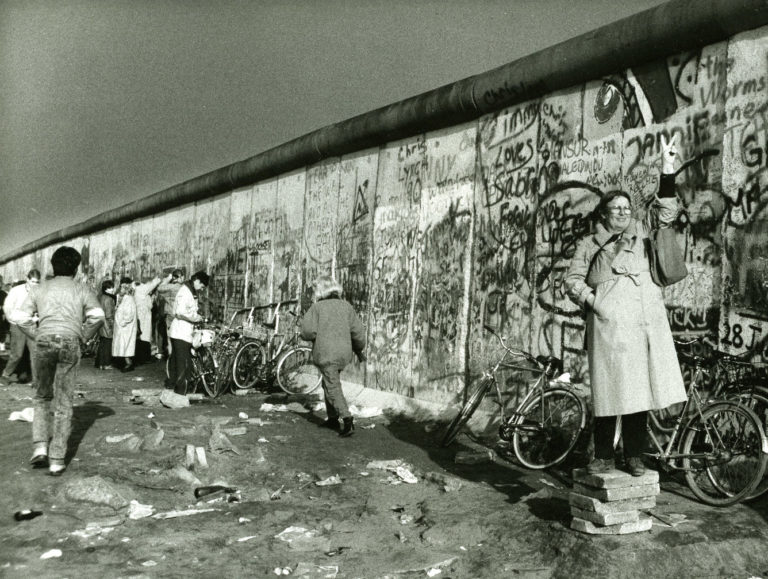

Was The Fall Of The Berlin Wall An Accident? – Mythbusting Berlin

On a seasonally crisp night in November 1989, one of the most astonishing events of the 20th century occurred. After twenty eight years, three months, and twenty eight days of defining and dividing the German capital, the Berlin Wall ceased to exist – at least in an abstract sense. Although the removal of this symbol of the failure of the East German system would take some time, its purpose – as a border fortification erected

Was The Nazi Party Democratically Elected? – Mythbusting Berlin

The myth persists that Adolf Hitler rose to power through popular democratic choice. Yet history reveals a darker, more complicated truth. Hitler’s ascent involved exploiting democratic institutions, orchestrating violence, propaganda, and political intrigue—not a simple election victory. Understanding how Germany’s democracy collapsed into dictatorship helps illuminate the dangerous interplay between public desperation, elite miscalculations, and extremist ambition, providing crucial lessons for safeguarding democracy today.

What Happened To Adolf Hitler’s Alligator? – Mythbusting Berlin

It is often said that you can tell a lot about a person by their relationship with animals; that owners often come to look and behave like their pets. Or is it perhaps more that people choose their pets to correspond to their personality? Nazi leader Adolf Hitler’s love of dogs, for example, is well documented but what is there to make of his relationship with reptiles?

What Was Checkpoint Charlie? – Mythbusting Berlin

Checkpoint Charlie remains among Berlin’s most visited historical sites, famed worldwide for its significance during the Cold War. Originally established as a modest border-crossing point, it evolved dramatically over the decades into an international symbol of freedom, espionage, and intrigue. Today, critics and locals often dismiss it as little more than a tourist trap—Berlin’s Disneyland—but how exactly did Checkpoint Charlie get its peculiar name, and what truths hide behind its popularity?

What Was Prussia? – Mythbusting Berlin

Prussia’s legacy is both remarkable and contentious—once a minor duchy, it rose dramatically to shape modern European history. Renowned for military discipline, administrative efficiency, and cultural sophistication, Prussia was instrumental in uniting the German states, laying foundations for a unified Germany. But how did this kingdom, with its roots in Baltic territories, achieve such prominence, and why does its complex history continue to evoke admiration, debate, and occasional discomfort in Germany today?

Who Built The Berlin Wall? – Mythbusting Berlin

One of the most common questions I have encountered from people curious about Berlin, and often so cryptically phrased. Who built the Berlin Wall? A simple five-word query, yet one that can be read one of two ways. More than thirty years since the ‘Fall of the Wall’, the story of its construction continues to baffle many who are mainly familiar with its existence through knowledge of its importance…

Who Really Raised The Soviet Flag On The Reichstag? – Mythbusting Berlin

One iconic photograph symbolizes the Red Army’s victory over Nazi Germany in 1945—the Soviet flag waving triumphantly above Berlin’s battered Reichstag building. Yet behind this enduring image lies controversy, confusion, and political manipulation. Who truly raised the Soviet banner atop the Reichstag? Was it a spontaneous act of heroism or carefully staged Soviet propaganda? Decades later, unraveling the truth reveals surprising layers beneath the mythologized symbol of Soviet triumph.

Who Was Really Responsible For The Reichstag Fire? – Mythbusting Berlin

Various theories have been posited as to who actually set fire to the German parliament in 1933. Was it the opening act in an attempted Communist coup or a calculated false flag operation carried out by elements of the Nazi Party, intended to create the conditions necessary for introducing single-party rule? And what part did the young man from Holland, arrested shirtless inside the building the night of the fire, play in this event?

Sources

Carter Hett, Benjamin (2014) Burning the Reichstag: An Investigation into the Third Reich’s Enduring Mystery. ISBN-13 : 978-0199322329

Delarue, Jacques (2008) The Gestapo. ISBN-13 : 978-1848325029

Eberle, Henrik & Uhl, Matthias (2014) The Hitler Book. ISBN-13 : 978-0884865704

Evans, Richard J (2003) The Coming of the Third Reich. ISBN-13 : 978-0141009759

Gilman, Sander & Rabinbach, Anson (2013) The Third Reich Sourcebook. ISBN-13 : 978-0520208674

Kershaw, Ian (2001) [2000]. Hitler, 1936–1945: Nemesis. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-04994-9.

Larson, Erik (2012) In the Garden of Beasts. ISBN-13 : 978-0552777773

Reitlinger, Gerald (1981) The SS: Alibi of a Nation 1922-1945. ISBN-13 : 978-0138399368

Richter, Jessen (2011) Voting for Hitler and Stalin. ISBN-13 : 978-3593394893

Ritchie, Alexandra (1998) Faust’s Metropolis. ISBN-13 : 978-0002158961

Shirer, William L. The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. ISBN 978-1451651683.