“The British and French peoples have advanced to rescue not only Europe but mankind from the foulest and most soul-destroying tyranny which has ever darkened and stained the pages of history. Behind them – behind us – behind the armies and fleets of Britain and France – gather a group of shattered States and bludgeoned races: the Czechs, the Poles, the Norwegians, the Danes, the Dutch, the Belgians – upon all of whom, the long night of barbarism will descend, unbroken even by a star of hope, unless we conquer, as conquer we must; as conquer we shall.”

Winston Churchill speaking on the BBC on May 19th 1940 in a speech entitled: ‘Be Ye Men of Valour’

Historians still debate whether the Nazi invasion of Poland in 1939 could be classified as the exact start of the Second World War; Czechoslovakia, occupied in 1938, would beg to differ. As would the citizens of Austria in 1937 – not all of them welcoming of a German annexation of that country.

Others have pointed to the start of the Spanish Civil War, and the consequences of the proxy involvement of Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, as the start of the great ideological clash of the 20th century between Fascism and Soviet Stalinism. Further back still, the Japanese invasion of Manchuria and the beginning of the fight against China.

As the First World War on the Western Front ended not with a great peace treaty but with an armistice and imposed penalties on the greatest perceived belligerent (Germany) – a popular argument of the 1920s and 30s that greatly influenced the rise of National Socialism was that the First World War had not even truly ended.

The German army, had it been able to unleash the full power of its reserves, could have conquered what the politicians were so eager to surrender in 1918 – and ‘Stab In The Back’ the brave soldier with cultivated political unrest at the front and at home.

There is plenty of mileage in the concept that the Second World War was merely an extension of the First – with some alliances reconfigured.

As the saying goes: all things end badly otherwise they would never end at all.

With that in mind, we search for the answer to the question often asked on private tours in the German capital – did the Second World War end in Berlin?

–

The Battle Of Berlin & The Last Battles Of The Second World War In Europe

“From day one, the eastern campaign claimed an exceptional number of losses. While a mere average of 2,100 Germans died daily, the death toll on the Soviet side – slain soldiers, starved POWs, murdered civilians – reached more than 14,100 a day. By the end of April 1945, at least twenty million Soviet nationals had lost their lives at the hands of the Germans whose towns and villages the Red Army soldiers were now rolling through with their tanks. It is unlikely that the Russian soldiers were aware of the precise figures, but they all knew that the Germans had set out to herd them into slave camps or throw their bodies into pits. Each one of them had cause for revenge and retribution, for feelings of hatred and triumph.”

Florian Huber, author of Promise Me You’ll Shoot Yourself

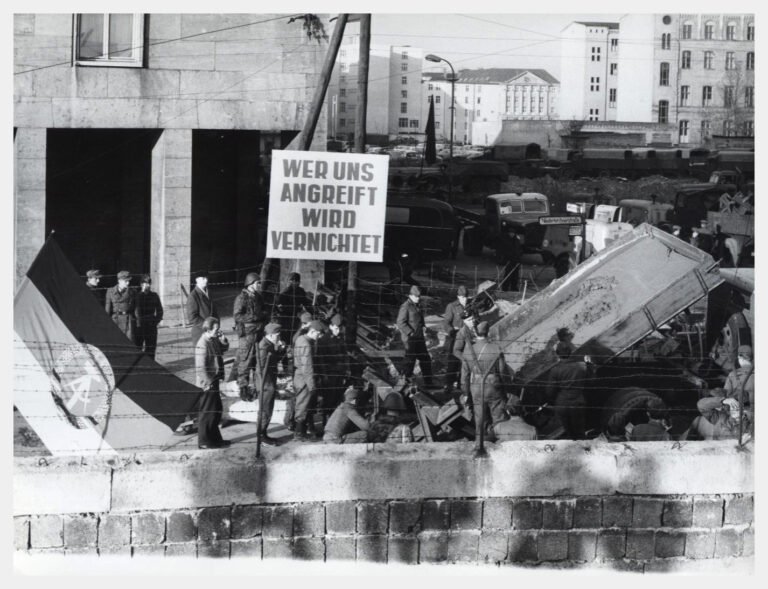

Walking distance from the Brandenburg Gate – and located within what is now Berlin’s central Tiergarten – is a memorial for the thousands of Soviet Red Army troops who fell fighting to conquer the nearby Reichstag in April and May 1945.

A number of inconsistencies are visible on the memorial, and another substantial cache of misinterpretations and myths are associated with it.

It is often said in guidebooks, and repeated ad nauseum by ignorant Berlin tour guides, that the two T-34 tanks at the front of the memorial were the first two of their kind to enter Berlin in April 1945. A story is immediately exposed as laughable when considering the reception Soviet troops received at the time – not of flowers and celebration, this was seen then as no liberation of the city as the Soviets would later present it, but with Panzerfausts and opposition to the death.

Similarly it is often said that the tanks contain the bodies of the tankers who died in them – an admission of the likelihood that they were in-fact damaged in the battle. If they were not simply fresh pieces brought straight off the production line for exhibition in Berlin. The T34 was, after all, and remains, the most produced tank in human history.

The claim that the artillery pieces featured were involved in the last barrage on central Berlin in May 1945 is more believable, as that was conducted from a safe enough distance for the pieces to survive untouched.

The most symbolic and controversial aspect of this memorial is, in-fact, hiding in plain sight.

Below the awkwardly out-of-proportion statue of the Soviet soldier can be found the dedication 1941-1945 – a reference to what was dubbed by the Soviets as the ‘Great Patriotic War’ at the time, a fight against the Fascist invaders who were only defeated once subdued in 1945.

That 1941 would be listed does expose some inherent bias – it is when the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union, codenamed Operation Barbarossa began. But it was also the moment when the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, signed between two foreign ministers of the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany, was violated. An agreement featuring a secret protocol to divide and occupy Europe together – establishing ‘Spheres of Influence’ – and maintained by the healthy exchange of raw materials (from the Soviet side) for technical expertise and support (from the Nazi side).

There is no mention here that these two states would be responsible for dividing and occupying neutral Poland in 1939 – the year counted by English schoolchildren as the start of the Second World War, when Great Britain and its colonies declared war only on Nazi Germany.

For children in the United States, the presence of 1941 would make more sense, coinciding with the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour and the ensuing declaration of war on the United States by Nazi Germany that led to the official US entrance into the conflict.

It is easy though to see why 1945 would be listed on this Soviet War Memorial.

For, from April 20th 1945 until the surrender of Berlin on May 2nd 1945, around 2.5 million Soviet troops surrounded the Nazi capital and fought their way – street by street, house by house, cellar by cellar – into the beating heart of the fascist beast.

The battle, as Antony Beevor details with harrowing clarity in his book The Fall of Berlin 1945, was a brutal culmination of years of unimaginable violence on the Eastern Front. The Red Army, having endured the depths of Nazi barbarity, was driven by a potent mixture of strategic necessity and a burning desire for revenge. Political instructors reinforced the message, reminding soldiers of the atrocities committed by the Wehrmacht and SS.

The result was a storm of retribution, with Berlin’s civilians caught in the vortex.

Inside the city, the defence was a desperate, fanatical, and ultimately futile affair. The fighting force was a motley crew of exhausted Wehrmacht soldiers, elderly Volkssturm (people’s militia), Hitler Youth boys as young as fourteen, and die-hard SS units, including foreign volunteers from the ‘Charlemagne’ and ‘Nordland’ divisions. They faced the overwhelming might of Marshal Georgy Zhukov’s 1st Belorussian Front and Marshal Ivan Konev’s 1st Ukrainian Front.

The human cost was staggering; in the battle for Berlin and the preceding Seelow Heights, the Soviets suffered over 350,000 casualties, while German military losses are estimated at nearly 100,000 killed, with hundreds of thousands more taken prisoner. Civilian deaths were in the region of 125,000.

Deep beneath the Reich Chancellery, in the claustrophobic Führerbunker, the Nazi regime consumed itself.

As shells rained down on the government district, Adolf Hitler married his long-term partner Eva Braun in a bizarre ceremony on April 29th. The following day, with Soviet troops a few hundred metres from his bunker, they committed suicide. Their bodies then hastily cremated in the Chancellery garden, a Götterdämmerung not for the Reich, but for its architect.

The most iconic moment of the battle was the fight for the Reichstag.

Though strategically irrelevant, its symbolic value was immense. According to Soviet lore – after undeniably ferocious fighting – two Soviet soldiers, Meliton Kantaria and Mikhail Yegorov, hoisted the Red Banner atop the blackened building on the evening of April 30th. The famous photograph capturing this event was, like much of the war’s imagery, staged and re-enacted for propaganda purposes a couple of days later.

With Hitler dead, the command of Berlin’s defence fell to General Helmuth Weidling. Recognising the hopelessness of the situation and wishing to spare the remaining civilians and soldiers, he arranged the surrender of the city.

On May 2nd, 1945, Weidling was driven to the headquarters of Soviet General Vasily Chuikov—the famed defender of Stalingrad—in a Tempelhof apartment building to sign the official capitulation of Berlin.

The beast’s heart had stopped beating.

Yet, even as the guns fell silent over the rubble of the German capital and its leader lay dead, the war was not over.

The surrender of a single city, even one as significant as Berlin, was not the surrender of a nation or its armed forces, which were still scattered across a contracting front. This act was but a prelude to a far more complex and drawn-out series of capitulations.

–

The Many Surrenders Of 1945

“You must understand three things: Firstly, you must surrender to me unconditionally all the German forces in Holland, Friesen and the Frisian Islands and Helgoland and all other islands in Schleswig-Holstein and in Denmark. Secondly, when you have done that, I am prepared to discuss with you the implications of that surrender… If you don’t agree to Point 1, the surrender, then I am going to go on with the war and I will be delighted to do so.”

British Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery, addressing the German delegation at Lüneburg Heath in May 1945

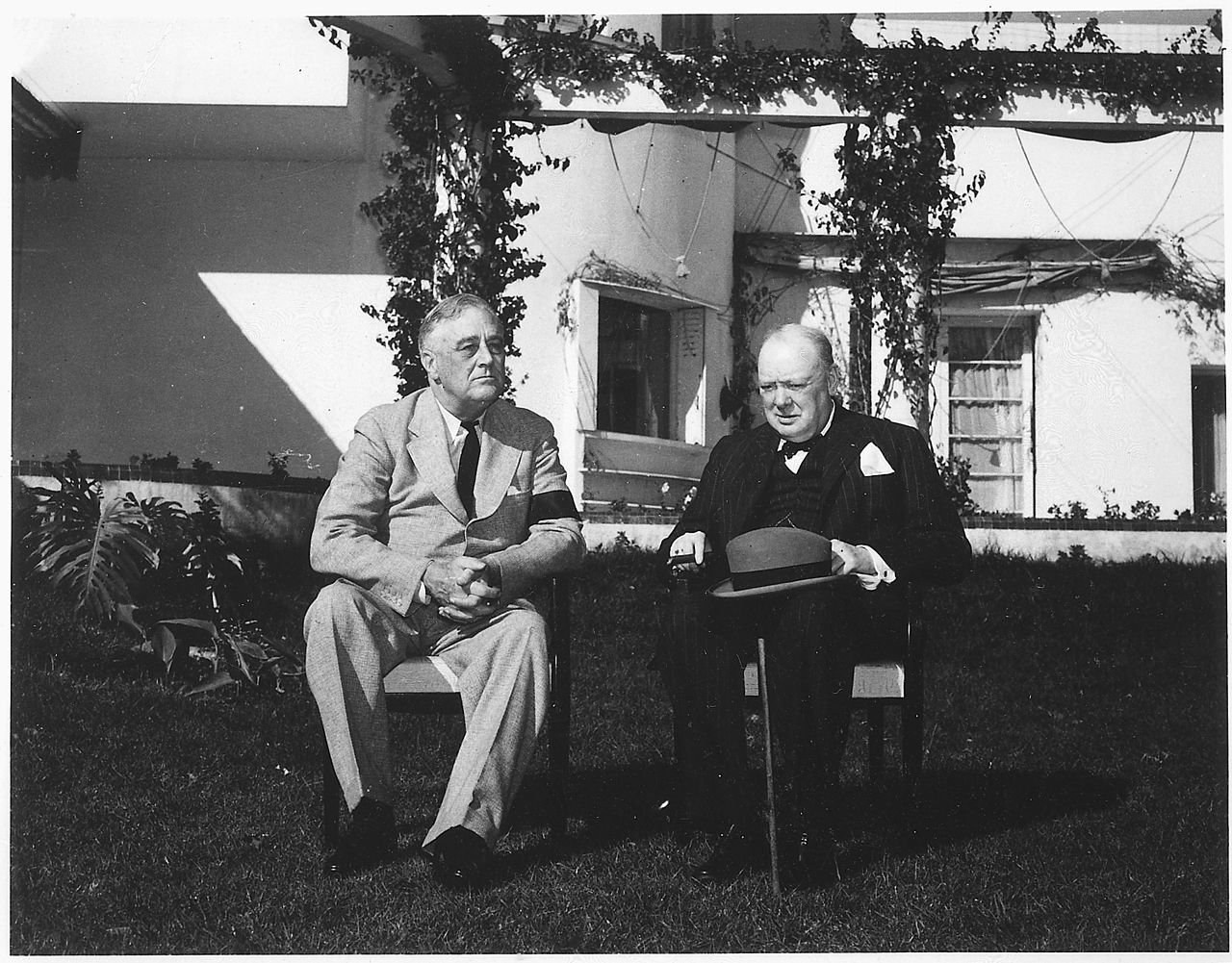

The path to the final end of the war in Europe had been conceptually paved years earlier. In January 1943, at a conference in Morocco, U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, alongside British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, laid down a foundational principle for the war’s conclusion.

Meeting in the recently liberated city of Casablanca, Roosevelt announced that the Allies would accept nothing less than the “unconditional surrender” of the Axis powers. A stance deliberately designed to avoid a repeat of the “stab-in-the-back” myth that had poisoned Germany after 1918.

There would be no negotiated armistice, no room for ambiguity; only the complete and total military defeat of Germany, Italy, and Japan.

Roosevelt clarified this did not mean the “destruction of the populations,” but rather “the destruction of the philosophies in those countries which are based on conquest and the subjugation of other people.”

The surrenders came in stages, reflecting the piecemeal collapse of the Axis.

The first major partner to fall was Italy.

Though a preliminary armistice was signed in secret on September 3rd, 1943, the situation remained chaotic, with German forces quickly disarming their former allies and occupying large swathes of the country. The fighting in Italy was a long, bloody slog.

The final, definitive German surrender on the Italian front only came on April 29th, 1945, when representatives signed the Instrument of Surrender at Caserta, taking effect on May 2nd – the same day Berlin fell.

Lt. Col. Victor von Schweinitz – on behalf of General Heinrich von Vietinghoff, as commander of Army Group C – and Major Eugen Wenner – on behalf of SS Obergruppenführer Karl Wolff, as commander of the Supreme SS and Police Leader in Italy surrendered to Lt. Gen. William Duthie Morgan – on behalf of Field Marshal Harold Alexander, as commander of the 15th Army Group.

A notable part in this surrender being that the SS – part of the Nazi Party and not the German Armed Forces – participated in the capitulation.

As the Third Reich crumbled in late April and early May 1945, its command structure fractured, leading to a series of partial capitulations.

On May 4th, at Lüneburg Heath in northern Germany, British Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery accepted the surrender of over a million German soldiers in the Netherlands, northwest Germany, and Denmark. It was a momentous event, but it was regional.

The Soviets, who had done the vast majority of the fighting and dying on the Eastern Front, were deeply suspicious of these separate surrenders. Stalin feared the Western Allies might negotiate a peace that would leave the Red Army to face the remaining Wehrmacht divisions alone. He was adamant that any general surrender must be a single event, with full Soviet participation.

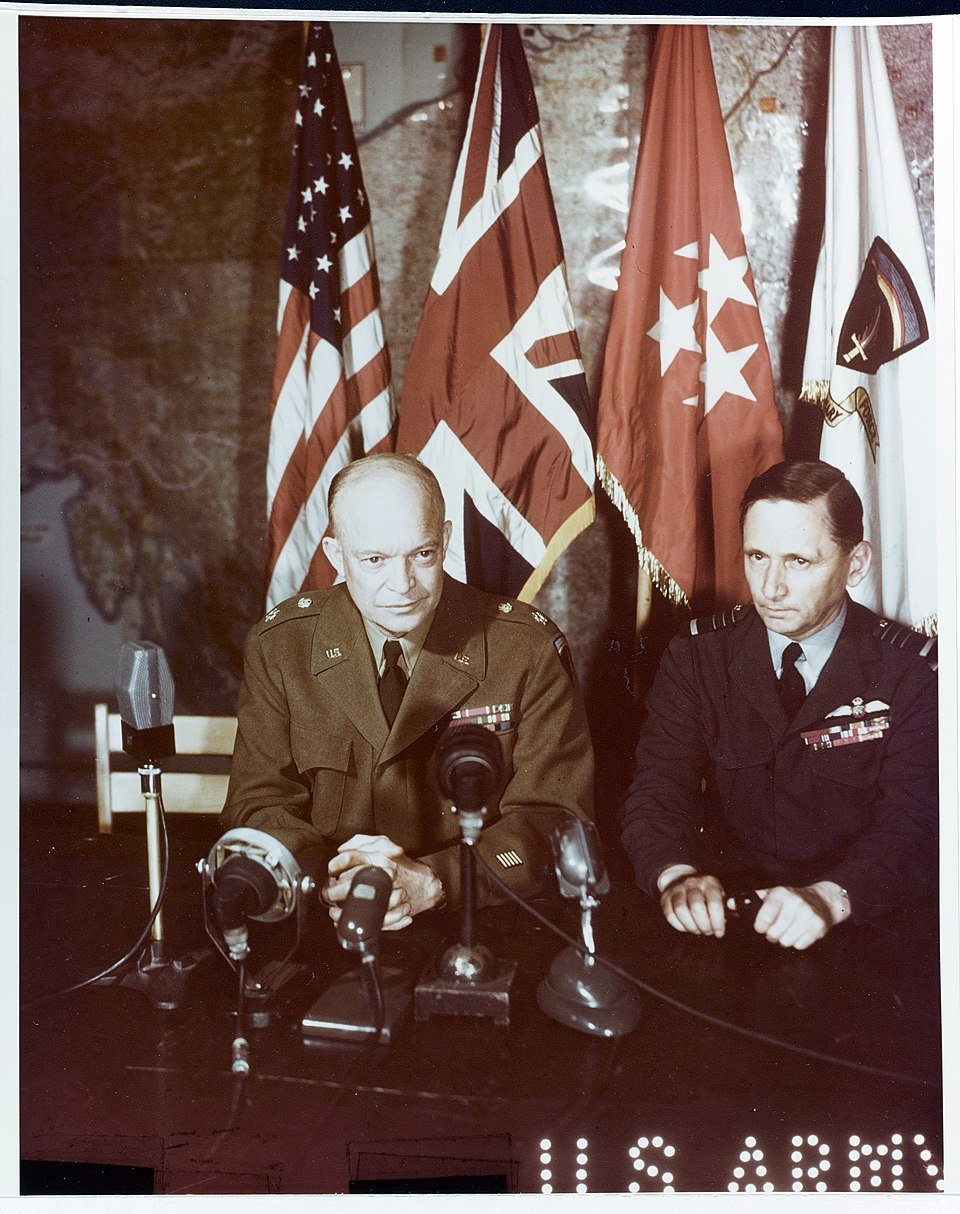

The surrender that has often been mislabelled as the final one took place on May 7th, 1945, in a red brick schoolhouse in Rheims, France, which served as the headquarters for the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF), commanded by U.S. General Dwight D. Eisenhower.

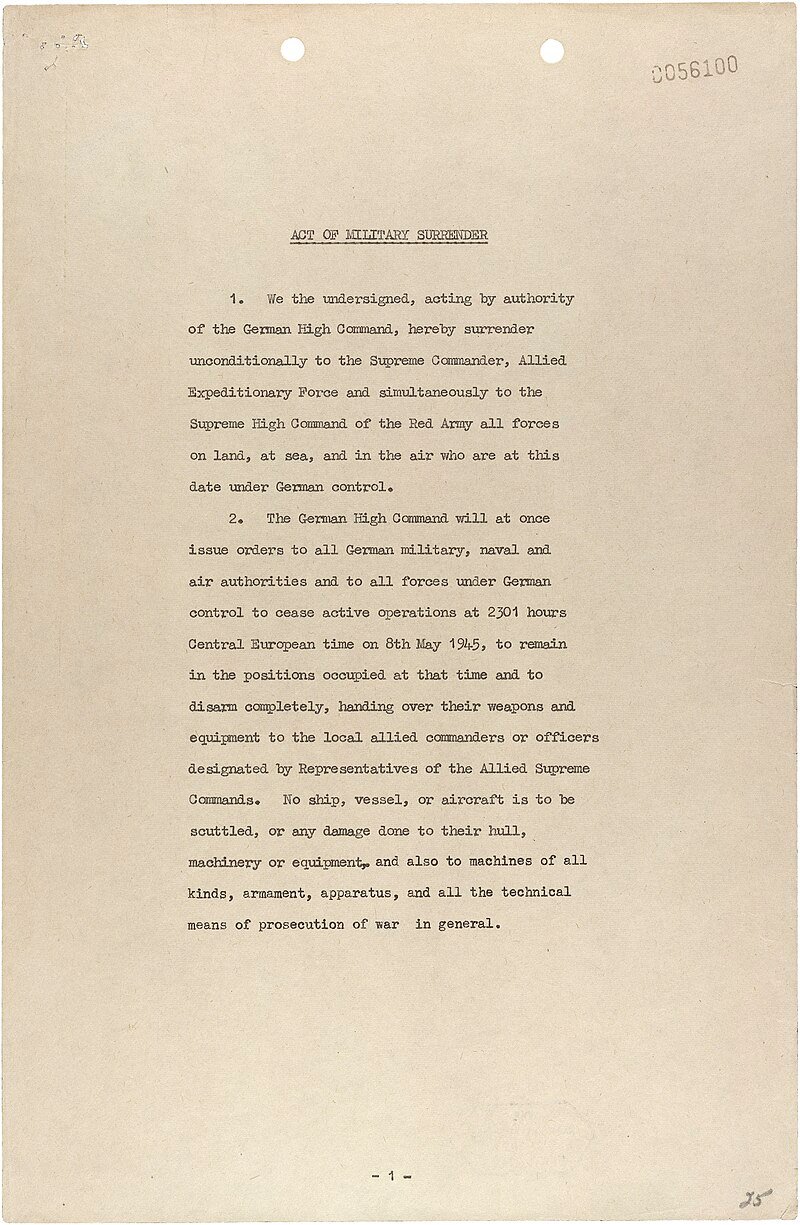

At 2:41 a.m., Colonel-General Alfred Jodl, Chief of the Operations Staff of the Armed Forces High Command, signed the act of unconditional surrender for all German forces. An immediate ceasefire was announced, with the surrender to take effect at 23:01 the following night.

This, however, was not the end.

The Soviet representative in Rheims, General Ivan Susloparov, signed the document but, lacking explicit instructions from Moscow, prudently added a note that it should be superseded by a “general act of capitulation.”

Stalin was furious when he heard the news, viewing the Rheims surrender as a betrayal and an attempt to rob the Soviet Union of its role in the final victory.

To appease Stalin and to ensure the German High Command itself ratified the surrender, a final, definitive ceremony was deemed essential.

The location was to be Berlin, the Nazi capital, only recently conquered by the Red Army.

The surrender at Rheims was, in effect, a dress rehearsal for the main event, a necessary but insufficient step on the road to a lasting peace, leading directly to one last formal act in the smouldering ruins of the vanquished capital.

–

The Surrender In Berlin

“Being aware of the wolfish habits of the German ringleaders, who regard treaties and agreements as empty scraps of paper, we have no reason to trust their words. However, this morning, in pursuance of the act of surrender, the German troops began to lay down their arms and surrender to our troops en masse. This is no longer an empty scrap of paper. This is actual surrender of Germany’s armed forces.”

Joseph Stalin in a broadcast in 1945 shortly after the surrender at Karlshorst

In the eastern Berlin suburb of Karlshorst, a former Wehrmacht pioneer school that had been repurposed as the headquarters for Marshal Zhukov and his 1st Belorussian Front, history was waiting to be made.

This district, with its grand houses, had ironically become the administrative heart of the Soviet conquerors. It was here, in a building that had once trained German army engineers, that the final act of surrender in the European theatre would be staged.

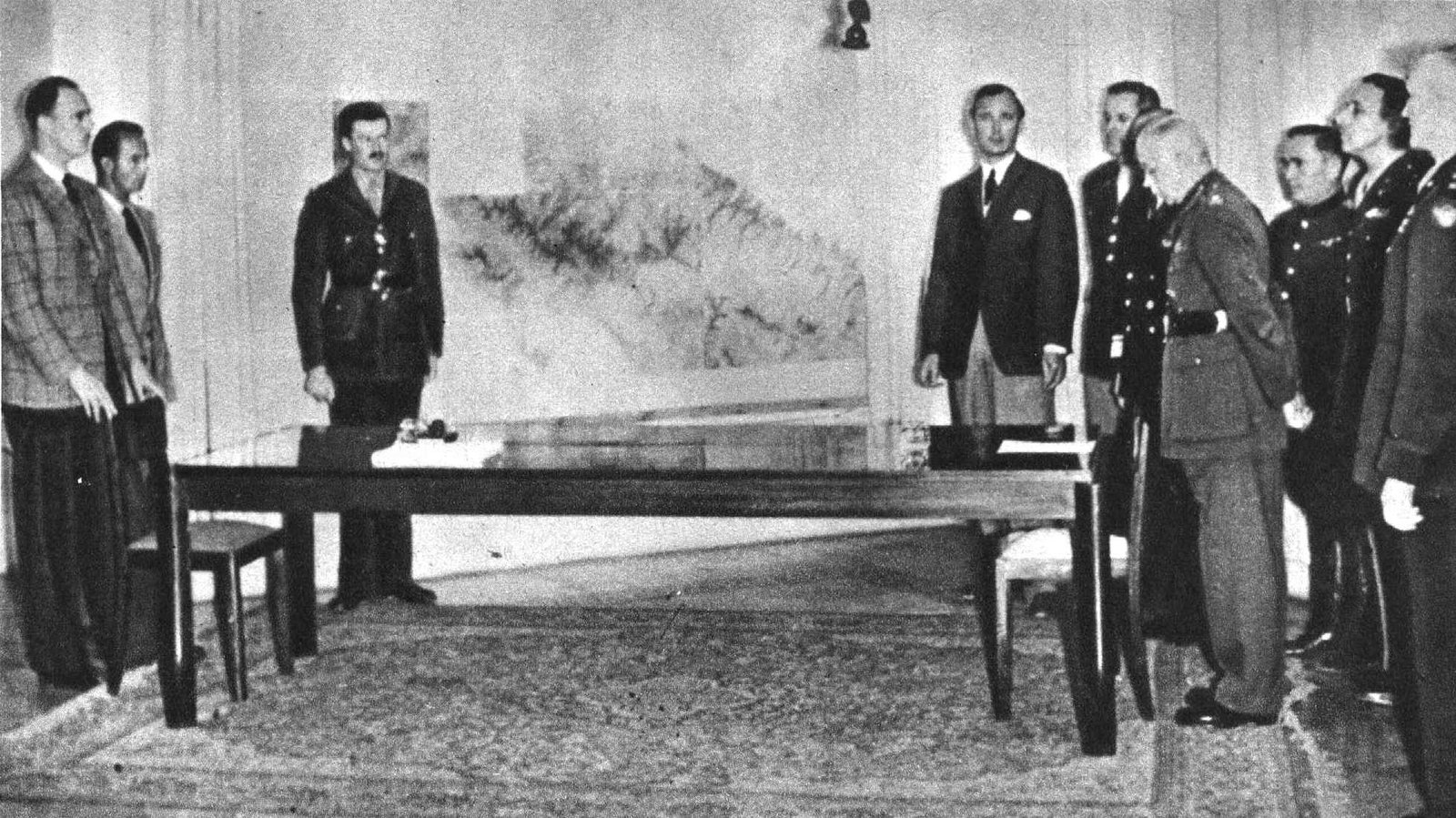

On the night of May 8th 1945, representatives of the victorious Allies finally received the official surrender of the armed forces of Nazi Germany, in a former army officers’ mess hall.

Soviet Marshal Georgy Zhukov, presided on behalf of the Supreme High Command of the Red Army, with Marshal Arthur Tedder of the Royal Air Force, representing the Allied Expeditionary Force and Eisenhower.

Three representatives of the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (OKW) had been flown in earlier in the day from Flensburg, the seat of the rump Nazi government led by Admiral Karl Dönitz. Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel, as Chief of the General Staff of the German Armed Forces (Wehrmacht); General-Admiral Hans-Georg von Friedeburg as Commander-in-Chief of the German Navy (Kriegsmarine); and Colonel-General Hans-Jürgen Stumpff as the representative of the German Air Force (Luftwaffe).

Upon seeing the British, French, and American representatives, Keitel is said to have sardonically remarked, “What? Have they surrendered to them too?”

When finally met by the Allied representatives late that evening, they engaged in deliberations until the instrument of surrender was finally signed at 00:16 on May 9th (Central European Time).

Due to the time difference – and to align with the earlier signing in Rheims – Victory in Europe Day is celebrated on May 8th in the West, but on May 9th in Russia and other post-Soviet states.

Hitler’s absence would not be the only remarkable detail of this momentous historical event. In-fact, none of the notorious Nazi Party personalities would partake in the surrender process.

The signing in Karlshorst was considered a vital precaution.

To counter any lingering sentiment that the Nazi war machine had been anything but conclusively defeated. This was clearly not a surrender signed by civilian politicians, as in 1918, but by the highest-ranking commanders of the German military. Keitel, von Friedeburg, and Stumpff were officers with actual power of command, underscoring the total and irrefutable military defeat.

The signing ceremony itself was brief, lasting around 45 minutes, conducted under the flags of the four victorious powers (Britain, the United States, the Soviet Union, and France). The German delegation, grim-faced, entered the hall, listened to the terms – briefly objected to the immediate aspect of the unconditional surrender, that would condemn many troops to capture by the Soviets – and signed.

The final three words uttered by Field Marshal Keitel, agreeing to the terms of unconditional surrender: “Ja, in Ordnung.” (Yes, in order.).

Marshal Zhukov proposed a toast to the victory of the anti-Hitler coalition, and a huge banquet was held for all the Allied representatives.

While the German delegation was allowed to eat – they would be prohibited from drinking and celebrating their own downfall.

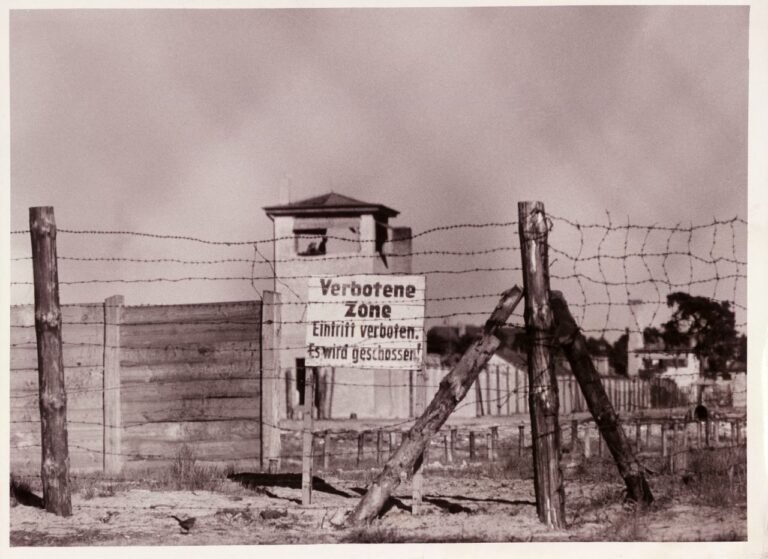

Following the partition of Berlin, Karlshorst and the building itself would fall under Soviet control, serving as the headquarters of the Soviet Military Administration.

In 1967, it became the “Museum of the Unconditional Surrender of Fascist Germany in the Great Patriotic War 1941-45.” Today, it is the Berlin-Karlshort Museum.

With this surrender, the war in Europe was officially over.

The fighting, however, was not.

–

The Surrender Of Japan

“The emperor is identical to the Great Sun Goddess Amaterasu. He is the supreme and only God of the universe, the supreme sovereign of the universe. All the many components of a country including such things as its laws and constitution, its religion, ethics, learning, and art are expedient means by which to promote unity with the emperor. That is to say, the greatest mission of these components is to promote an awareness of the self-everything in the universe is a manifestation of the emperor. Because of the non-existence of the self other than the emperor, including even the insect chirping in the hedge, or the gentle spring breeze.”

Lieutenant Colonel Sugimoto Goro, author of ‘Great Duty (Taigi) – 1938

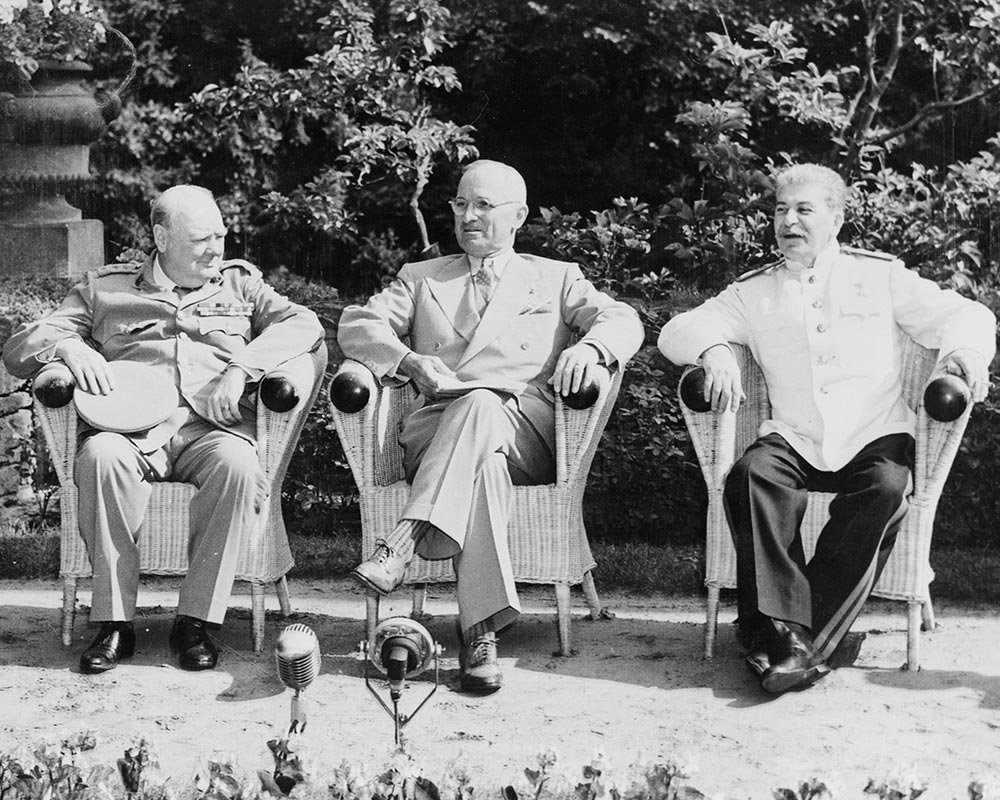

In July 1945, two months after the guns fell silent in Europe, the leaders of the ‘Big Three’ met amidst the faded grandeur of a Hohenzollern palace in Potsdam, just outside Berlin.

The atmosphere was different. Harry S. Truman, new to the presidency after Roosevelt’s death, represented the United States. Clement Attlee replaced Churchill mid-conference after a stunning electoral defeat. By the end of the proceedings, only Joseph Stalin remained of the original wartime trio.

While the conference’s main agenda was to decide the fate of a defeated Germany and redraw the map of Europe, a giant shadow loomed from the other side of the world: the ongoing war in the Pacific.

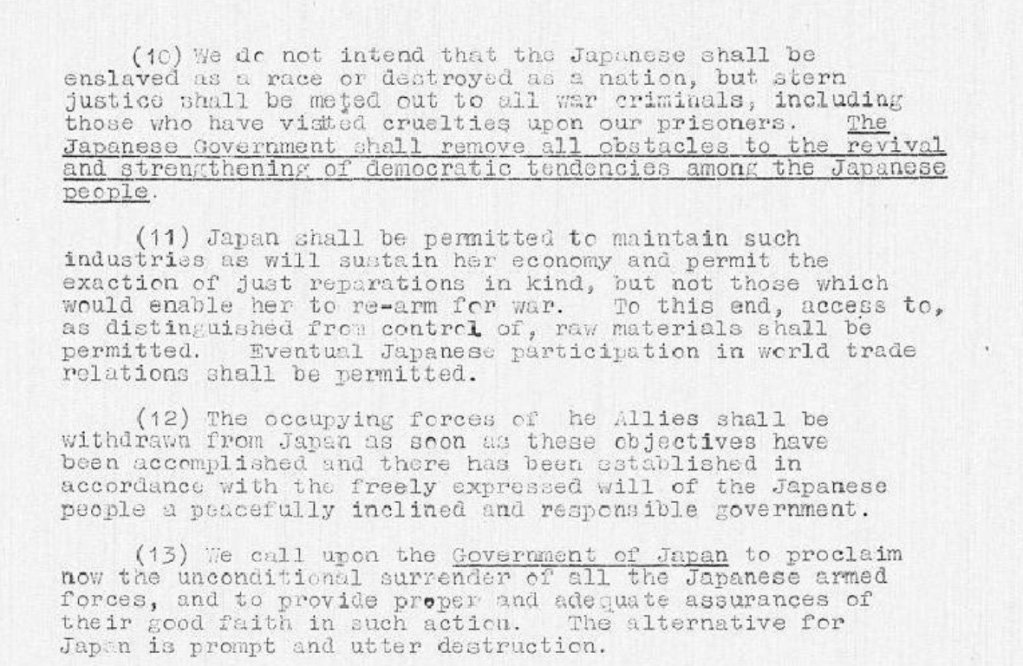

On July 26th, on the sidelines of the main negotiations, the United States, Britain, and China issued the Potsdam Declaration.

It was a stark ultimatum delivered to the Empire of Japan: surrender unconditionally or face “prompt and utter destruction.” Stalin was not a signatory; the Soviet Union was still, at this point, neutral in the Pacific War.

The Japanese government, led by Prime Minister Kantarō Suzuki, met the declaration with what they termed mokusatsu, a word with deliberate ambiguity, interpreted by the Allies as “to kill with silence” or to treat with silent contempt.

The ultimatum had been rejected.

It was during this conference that the course of the war—and the future of the world—would be irrevocably altered.

On July 16th, Truman had received a coded message informing him of the successful test of a new weapon of “unusual destructive force” in the New Mexico desert.

On July 24th, Truman approached Stalin. “I casually mentioned to Stalin that we had a new weapon,” Truman wrote in his memoirs. Stalin showed little outward interest, replying only that he hoped the Americans would make “good use of it against the Japanese.”

Unbeknownst to Truman, Stalin was already well-aware of the Manhattan Project through his network of spies. Truman’s “reveal” was more of a confirmation, a subtle move in the emerging chess game of the post-war world.

Here at Potsdam, Truman gave his military the final authorization to use the atomic bombs once the conference had concluded.

For months, the U.S. had been executing a brutal island-hopping campaign across the Pacific, fighting its way closer to the Japanese home islands. Battles on islands like Iwo Jima and Okinawa had demonstrated the Japanese military’s willingness to fight to the last man, resulting in horrific casualties on both sides.

Projections for a full-scale invasion of Japan, codenamed Operation Downfall, anticipated millions of Allied and Japanese casualties.

The atomic bomb presented a chilling alternative to this predicted bloodbath.

![Harry Truman's handwritten note authorising the release of the world's first atomic bomb - "Sec. War Reply to your 41011 [the number of the telegram] suggestions approved Release when ready but not sooner than August 2" - Public Domain](https://berlinexperiences.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/berlinexperiences_mythbustingberlin_secondworldwar_15.jpg)

On August 6th 1945, President Truman, on the return journey back to the United States from Potsdam, was enjoying the sun on the deck of the S.S. Augusta.

After a concert by the ship’s band and lunch with the crew, a message was handed to him. It read: ‘HIROSHIMA BOMBED VISUALLY…RESULTS CLEAR-CUT SUCCESSFUL IN ALL RESPECTS. VISIBLE EFFECTS GREATER THAN IN ANY TEST.’ Truman shook the hand of the officer who delivered the message and declared, “This is the greatest thing in history.”

Following a second, confirmatory message from Secretary of War Henry Stimson, Truman excitedly told his Secretary of State, Jimmy Byrnes, “It’s time for us to get on home!” He then announced to the crew that a powerful new bomb had been successfully deployed.

In Japan, the country’s most distinguished nuclear scientist, Dr. Yoshio Nishina, was dispatched to confirm the nature of the weapon. Surveying the utter devastation, he concluded it was a uranium bomb. Initial estimates suggested as many as 100,000 people were killed instantly, with another 100,000 dying from injuries and radiation. The news prompted a furious Stalin to order his own scientists to develop an atomic bomb with all possible speed.

Despite the horror of Hiroshima, the Japanese militarists remained intransigent.

The next move came from Moscow.

On August 8th, Soviet Foreign Minister Molotov bluntly informed Japanese Ambassador Sato that as of the following day, “the Soviet Union will consider herself in a state of war against Japan.” Molotov then had the embassy’s communications cut, ensuring the declaration would reach Tokyo via a public broadcast hours later.

As the Red Army poured into Japanese occupied Manchuria in the pre-dawn hours of August 9th, the American B-29 bomber Bock’s Car was already airborne, carrying a plutonium bomb nicknamed ‘Fat Man’—a nod to Winston Churchill.

While Prime Minister Suzuki was telling his cabinet, “our only alternative is to accept the Potsdam Proclamation,” the second atomic bomb devastated Nagasaki.

Still, the military leaders in the cabinet refused to yield, intent on a final, bloody defence of the homeland. It took a final, unprecedented intervention from Emperor Hirohito himself in the early hours of August 10th to force the decision. He ordered an end to the war.

The final, formal end of the War in the Pacific came on September 2nd, 1945.

On the deck of the USS Missouri, anchored in Tokyo Bay, representatives of the Japanese Empire signed the Instrument of Surrender in front of General Douglas MacArthur and delegates from all the Allied nations.

The long, global nightmare was finally over.

Or was it?

One week after the surrender of the Japanese to the Allied forces, a final surrender was held in Nanking to the representatives of China.

Ending a war that had begun on 8 years, 1 month, 3 weeks and 5 days earlier – on July 7th 1937 – with the start of what is referred to as the Second Sino-Japanese War.

After the Allied victory in the Pacific, US General Douglas MacArthur had ordered all Japanese forces within China (excluding Manchuria), Taiwan and French Indochina north of 16° north latitude to surrender to Chiang Kai-shek, and the Japanese troops in China formally surrendered on September 9th 1945, at 9:00.

The ninth hour of the ninth day of the ninth month was chosen in echo of the Armistice of 11 November 1918 (on the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month) and because “nine” (九 jiǔ) is a homophone of the word for “long lasting” (久) in Chinese (to suggest that the peace won would last forever).

–

Conclusion

“Despite the best that has been done by everyone… the war situation has developed not necessarily to Japan’s advantage, while the general trends of the world have all turned against her interest. Moreover, the enemy has begun to employ a new and most cruel bomb, the power of which to do damage is, indeed, incalculable, taking the toll of many innocent lives… Should we continue to fight, it would not only result in an ultimate collapse and obliteration of the Japanese nation, but also it would lead to the total extinction of human civilization… We have resolved to pave the way for a grand peace for all the generations to come by enduring the unendurable and suffering what is insufferable.”

Japanese Emperor Hirohito, in his historic radio broadcast to the Japanese people (the Gyokuon-hōsō), August 15th 1945

So, did the Second World War end in Berlin?

The answer is both yes and no.

The war in Europe, the titanic struggle against Nazi Germany and its allies, reached its definitive, legal, and symbolic conclusion in the Berlin suburb of Karlshorst late on the evening of May 8th, 1945. This was the moment the Wehrmacht, as a unified entity, ceased to exist. In this crucial respect, Berlin was indeed the end.

However, the Second World War was a global conflict. While Berliners celebrated a grim peace amidst the ruins of the Nazi capital, ferocious fighting continued in the Pacific.

The full, unconditional surrender of all the major Axis powers—the goal set at Casablanca—was not achieved until the Japanese instrument of surrender was signed in Tokyo Bay on September 2nd.

Thus, Karlshorst marks the end of a critically important chapter, but not the end of the book.

Berlin was the site of the war’s European finale, but the global curtain call, the moment that finally brought silence – if only temporary – to the world’s battlefields, took place four months later, thousands of miles away.

The war’s end was not a single moment, but a series of conclusions, a complex unwinding that had its most poignant European moments in the rubble of the city where so much of it began.

***

If you’ve enjoyed reading this article, consider booking one of our private guided tours of Berlin.

Sources

Arendt, Hannah (1951), The Origins of Totalitarianism, Harcourt, Brace & Company, ISBN 978-0-15-670153-2.

Beevor, Antony (2002), The Fall of Berlin 1945, Viking, ISBN 978-0-670-03077-2.

Dobbs, Michael (2012), Six Months in 1945: FDR, Stalin, Churchill, and Truman — From World War to Cold War, Knopf / Alfred A. Knopf, ISBN 978-0307271655.

Fest, Joachim (2004), Inside Hitler’s Bunker: The Last Days of the Third Reich, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, ISBN 978-0374135778.

Hamilton, Aaron Stephan (2020), Bloody Streets: The Soviet Assault on Berlin (Revised and Expanded Second Edition), Helion & Company, ISBN 978-1912866137.

Huber, Florian (2020), Promise Me You’ll Shoot Yourself: The Mass Suicide of Ordinary Germans in 1945, Penguin Books, ISBN 978-0141990774.

Jähner, Harald (2022), Aftermath: Life in the Fallout of the Third Reich, 1945–1955, WH Allen, ISBN 978-0753557884.

Kershaw, Ian (2011), The End: Hitler’s Germany, 1944–1945, Allen Lane / Penguin Books, ISBN 978-0141014210.

Kershaw, Ian (2015), The Nazi Dictatorship: Problems and Perspectives of Interpretation, Bloomsbury Revelations, ISBN 978-1-4725-8810-4.

Lüh, Jürgen (2020), Potsdam Conference 1945: Shaping the World, Sandstein Kommunikation GmbH, ISBN 978-3954985470.

Mee, Charles L., Jr. (1975), Meeting at Potsdam, M. Evans & Company, ISBN 978-0871311672.

Montefiore, Simon Sebag (2003), Stalin: The Court of the Red Tsar, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, ISBN 978-0297843350.

Rabinbach, Anson; Gilman, Sander L. (eds.) (2013), The Third Reich Sourcebook, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-22064-4.

Ryan, Cornelius (1966), The Last Battle, Simon & Schuster, ISBN 978-0684803296.

Truman, Harry S. (1955), Memoirs: Volume 1, Year of Decisions, Doubleday & Company, ISBN 978-0385058632.

Victoria, Brian Daizen (2006), Zen at War (Second Edition), Rowman & Littlefield, ISBN 978-0742539266.

Weinberg, Gerhard L. (1994), A World at Arms: A Global History of World War II, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0521443173.

HISTORICAL ARTICLES

Mythbusting Berlin

Are There Any Nazi Statues Left In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

Visitors to Berlin often arrive expecting to find the physical remnants of the tyranny of the 20th century still standing – statues of dictators, triumphal arches, or bronze idols. Instead, they often find none. The stone symbols and statues of the Third Reich are still gazing down on them, however, hiding in plain sight. But why are there no statues of Hitler? Did the Allies destroy them all in 1945, or is the truth stranger

Could The Western Allies Have Captured Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

To contemplate a Western Allied capture of Berlin in 1945 is to challenge the established endgame of the Second World War. What was the true military and logistical feasibility of a Western Allied assault on the Nazi capital? What factors truly sealed Berlin’s fate, and what might have changed had the Allies pushed eastward?

Answering these questions means delving into the complex interplay of logistics, political maneuvering, and the competing visions for a post-war world

Did Any Of The Rothschild Dynasty Die In The Holocaust? – Mythbusting Berlin

The Rothschild name is synonymous with immense wealth, influence, and persistent conspiracy theories—especially during the era of Nazi Germany. Often targeted by antisemitic propaganda, the family’s survival during World War II has sparked myths about their supposed immunity from Nazi persecution. But did any Rothschild family member actually perish in the Holocaust? This article explores that compelling question, unraveling historical misconceptions and revealing the reality behind one of Europe’s most famous dynasties.

Did Frederick The Great Introduce The Potato To Germany? – Mythbusting Berlin

One of the more bizarre claims to fame attributed to the first King of Prussia is that the man who would go down in history known as Frederick the Great introduced the potato to Germany during his reign back in the 1700s. This starchy root vegetable has undoubtedly become a staple part of German cuisine – an essential addition to any plate of Schnitzel, Schweinshaxn, and Königsberger Klopse – however, whether Frederick the Great is

Did Hitler Escape To Argentina In 1945? – Mythbusting Berlin

Although Nazi leader, Adolf Hitler, certainly remains an inescapable figure, could there be any truth to the story of his escape to Argentina in 1945? That the most wanted man on earth could simply vanish, to spend the rest of his life peacefully in South American obscurity captivates imaginations. Yet, despite numerous investigations, this tale persists primarily as myth—fueled by speculation, hearsay, and conspiracy theories.

Did Hugo Boss Design The Nazi Uniforms? – Mythbusting Berlin

The idea that Hugo Boss – the man whose name now adorns expensive suits and fragrances – was the creative genius behind the Nazi uniforms suggests a terrifying collision of haute couture and holocaust – a marriage of high style and high crimes. The image is striking: a German tailor sketching the ultimate villain’s costume. But history, as usual, is far messier, more bureaucratic, and more banal than the internet memes suggest. To understand who

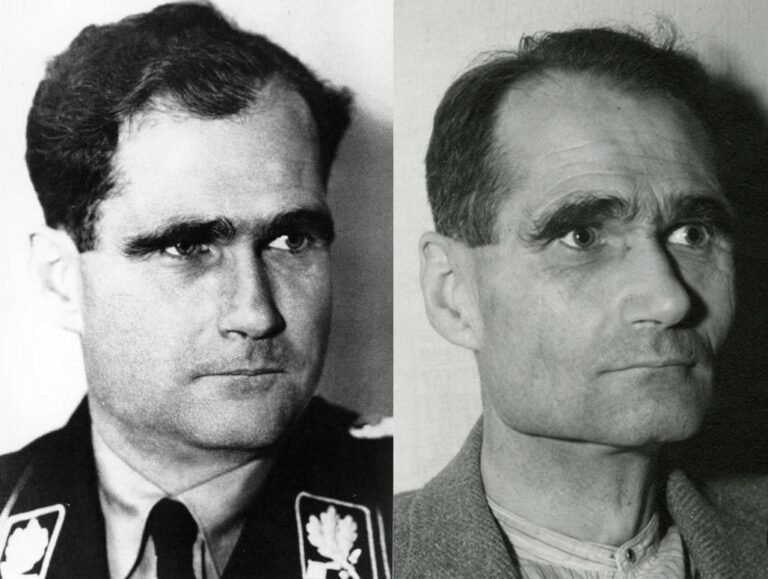

Did Rudolf Hess Really Commit Suicide? – Mythbusting Berlin

On a summer’s day in 1987, the last Nazi war criminal of the Nuremberg trials was found dead in a prison built for hundreds, yet for two decades, housed only him. The official verdict was suicide, a straightforward end to a life defined by fanaticism, delusion, and contradiction.

But the simplicity of the report belied the complexity of the man and the 46 years he had spent in Allied custody. In the meticulously controlled

Did The Nazis Develop Nuclear Weapons? – Mythbusting Berlin

The Nazi obsession with super-weapons became so serious in the closing stages of the Second World that Adolf Hitler personally believed that such ‘Wunderwaffen’ both existed in a usable form – and would save the country from defeat. Had the Nazis managed to develop nuclear weapons by 1945 – the outcome of the war would surely have been different. But how close were Hitler, Himmler, and his henchmen to developing an A-bomb?

Did The Nazis Invent Decaf Coffee? – Mythbusting Berlin

Persistent rumors claim that Nazis preferred their coffee anything but pure, leading some to wonder if they might have influenced the development of decaffeinated coffee. Although decaf was already widely available across Europe by the mid-20th century, speculation continues: could the Nazis really have played a role in popularizing—or even discovering—this caffeine-free alternative, or is this simply another caffeinated conspiracy cooked up to sensationalize an ordinary historical detail?

Did The Nazis Invent The Bicycle Reflector? – Mythbusting Berlin

The fruits of wartime ingenuity are plenty – so many, in-fact, that it has become somewhat of a worn cliche that as the guns start firing the innovators get to work, often solving problems while providing more problems for the enemy to overcome.The kind of progress that results in the production of newer improved, more lethal weapons, such as to increase the chances of victory.

Did The Nazis Run The Largest Counterfeiting Operation In History? – Mythbusting Berlin

During the Second World War the Nazis masterminded an astonishing plot to destabilise Britain by flooding its economy with counterfeit banknotes. Crafted in secret by concentration camp prisoners, this forged fortune became the most ambitious counterfeiting operation ever attempted. But was it history’s largest? Dive into the extraordinary tale of Operation Bernhard,

rife with deception, survival, and intrigue—revealing the truth behind one of the Third Reich’s most audacious schemes and its surprising legacy.

Did The Second World War End In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

When is a war ever truly over? When the last shot is fired in anger would seem like the best measure. Rarely, though, is it possible to gain insight into such a moment.

Remarkably, a record still exists of such a moment at the end of the First World War on the Western Front. A seismic register and recording of the last belching battery of British guns firing artillery across no-man’s-land, followed by a profound

Did The Spanish Flu Pandemic Help The Nazis Take Power? – Mythbusting Berlin

The devastating Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918-1919 struck amid Germany’s post-war turmoil, compounding social instability, economic hardship, and widespread political disillusionment. Could this catastrophic health crisis have indirectly paved the way for Nazi ascension? While often overshadowed by war and revolution, the pandemic’s profound psychological and societal impacts arguably contributed to the perfect storm, enabling extremist ideologies—including Nazism—to gain popularity and ultimately seize power in a fractured Germany.

Have Adolf Hitler’s Remains Been DNA Tested? – Mythbusting Berlin

In the smouldering ruins of Berlin in 1945, the world’s most wanted man vanished. Did Adolf Hitler, as official history attests, die by his own hand in the Führerbunker? Or did he escape, fuelling a thousand conspiracy theories that have echoed for decades? For years, the Soviets claimed to hold the gruesome proof of his death: a skull fragment and a set of teeth, locked away in Moscow archives. But in an age of definitive

How Did The Nazi Concentration Camps Differ From The Soviet GULAG?

The Nazi concentration camps and Soviet Gulag system have often been conflated in popular imagination—twin symbols of twentieth-century totalitarian horror. Yet the two systems operated on fundamentally different principles. One extracted labor to fuel industrialisation while accepting mass death as collateral damage; the other evolved into purpose-built machinery of genocide. Understanding these distinctions isn’t merely academic—it reveals how different ideologies produce different atrocities, and why Germany and Russia reckon with these legacies so differently today.

How Long Did It Take To Build The Berlin Wall? – Mythbusting Berlin

It is one of the most enduring images of the 20th century: a city divided overnight. The popular narrative tells us that Berliners went to sleep in a unified city and woke up in a prison. While the shock of August 13th 1961, was very real, the idea that the ‘Wall’ appeared instantly is a historical illusion. The physical scar that bisected Berlin was not a static creation, but a living, malevolent beast that evolved

How Many Assassination Attempts On Adolf Hitler Were There? – Mythbusting Berlin

Nazi leader, Adolf Hitler, projected an aura of invincibility, a man of destiny shielded by providence. But behind the carefully constructed image of the untouchable Führer lies a story of constant threat, of bombs that failed to detonate, and errant bullets that missed their mark. Unearth the hidden history of the numerous attempts on Hitler’s life as we explore the courage of those who tried to change the course of history and the devil’s luck

How Many Jews Died In The Holocaust? – Mythbusting Berlin

The answer to the question posed of how many Jews died in the Holocaust is a simple one: too many. That merely one death was an unforgivable obscenity is a fundamental and necessary realisation in understanding the capriciousness of this unparalleled racial genocide. To comprehend, however, the full number of Jews murdered in Europe by the Nazi regime in the 1930s and 1940s is a detective story of epic proportions: the evidence overwhelming, multifaceted, and

How Many People Died Trying To Escape East Germany? – Mythbusting Berlin

The image of the Berlin Wall is seared into our collective memory, a concrete symbol of Cold War oppression. We think of the daring escapes and the tragic deaths of those who failed. But that well-known number is only a fraction of the truth. The story of those who died trying to escape East Germany is far broader and more complex than most imagine, stretching along a thousand-kilometer border and out into the cold waters

How Old Is Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

A relatively new arrival in Europe, Berlin is over 1000 years younger than London, nevermind Rome or Athens, Jerusalem or Jericho. Just how old is Berlin though?

A question fraught with false assumptions and distortions – that has more often than not been answered with propaganda as it has with the cold hard truth.

Was Adolf Hitler A Drug Addict? – Mythbusting Berlin

Solving the enigma of the ‘Führer’ has become a preoccupation for many, since the arrival of the Austrian-German onto the world stage – although moving beyond the mythology without falling into the trap of prejudically extrapolating on the psychopathography of Hitler or demonising so as to excuse his actions has proven problematic. What to make of the man who became more than the sum of his masks? The painter; the military dilettante, the mass murderer,

Was Adolf Hitler A Freemason? – Mythbusting Berlin

History abhors a vacuum, but adores a mystery. Such is the speculative fiction suggesting a secret allegiance behind the rise of the Third Reich – that the catastrophe of the Second World War was orchestrated from the shadows of a Masonic lodge. The image of Adolf Hitler—the drifter from Vienna turned dictator—as a covert initiate of the very brotherhood he publicly reviled, however, creates a paradox that collapses under scrutiny. As when we unlock the

Was Adolf Hitler Gay? – Mythbusting Berlin

In the shadowy corridors of Third Reich history, few questions provoke as much tabloid curiosity and scholarly exasperation as the sexuality of Adolf Hitler. For decades, rumors have swirled—whispered by political enemies in 1930s Munich, psychoanalyzed by American spies in the 1940s, and sensationalized by revisionist authors today. Was the dictator who condemned thousands of men to concentration camps for “deviant” behavior hiding a secret of his own? By peeling back the layers of propaganda,

Was Adolf Hitler Jewish? – Mythbusting Berlin

Was the dictator who orchestrated the murder of millions of European Jews secretly one of them? It is perhaps the darkest irony imaginable, a story whispered for decades in backrooms, bars, and conspiracy forums alike. The most-common rumour – the ‘Frankenberger Myth’ – suggests that Adolf Hitler’s paternal grandfather was Jewish, a secret so damaging it could have unraveled the entire Nazi regime. But where does this claim come from? And, more importantly, is there

Was Currywurst Invented In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

Explore the story behind what many consider Berlin’s most iconic snack—the ever-so-humble Currywurst. Often hailed as an enduring symbol of culinary creativity amid Cold War scarcity, this humble dish has inspired fierce debate about its true origin. But was it genuinely invented here in Berlin, or have proud locals simply adopted and elevated this spicy street-food favorite into legendary status all their own?

Was Fanta Invented By The Nazis? – Mythbusting Berlin

As one of the most secretive organisations in the world, the Coca Cola corporation refuses to share its secret recipe with anyone. Famously insisting only on shipping the base syrup of its drinks to plants around the world to be carbonated and distributed.

This combined with the trade limitations of the Second World War may have led to the introduction of one of the most popular soft-drinks in the world. But could it be true:

Was Frederick The Great Gay? – Mythbusting Berlin

Frederick II of Prussia, better known as Frederick the Great, is often remembered as the archetypal enlightened monarch – a brilliant military commander, patron of the arts, and learned philosopher. Yet behind the stern portraits of this 18th-century warrior-king lies a personal life long shrouded in intrigue and speculation. Intrigue around the king’s sexual orientation has persisted through the centuries, chiefly revolving around one question: Was Frederick the Great gay?

Was Henry Ford A Nazi? – Mythbusting Berlin

US auto tycoon, Henry Ford, holds the ignominious distinction of being the only American Adolf Hitler praised by name in his National Socialist manifesto: ‘Mein Kampf’. This was not, as it turns out, the only connection between Ford and the Party of Hitler, Himmler, and the Holocaust.

Ford’s overt affinity with the Third Reich reveals a troubling past. How deep these connections ran, and how consequential they were for both sides, is a chapter

Was The Colour Blue Invented In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

Tracing the true history of blue—from ancient Egyptian dyes to the accidental discovery of Prussian Blue in a Berlin lab. We’ll debunk myths about seeing blue, explore colonial indigo plantations, scale mountains with a cyanometer, and trace Van Gogh’s starry skies—all to answer one question: how did Berlin shape our understanding of the world’s rarest color?

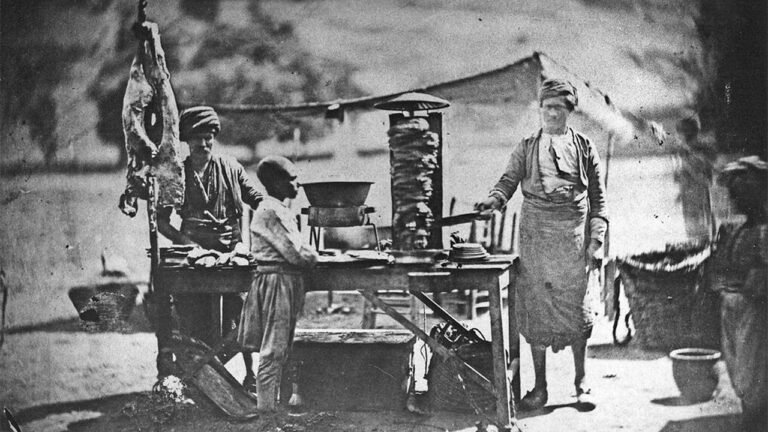

Was The Döner Kebab Invented In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

Unlikely icon of immigrant success; fast food symbol of the working class; over-hyped midnight disco eat; or culturally appropriated cuisine? Its influence goes far beyond layers of seasoned meat and fresh vegetables stuffed into pita bread. But does Berlin deserve credit as the Döner Kebab’s true birthplace, or has the city merely refined and popularized a culinary tradition imported from elsewhere?

Was The Fall Of The Berlin Wall An Accident? – Mythbusting Berlin

On a seasonally crisp night in November 1989, one of the most astonishing events of the 20th century occurred. After twenty eight years, three months, and twenty eight days of defining and dividing the German capital, the Berlin Wall ceased to exist – at least in an abstract sense. Although the removal of this symbol of the failure of the East German system would take some time, its purpose – as a border fortification erected

Was The Nazi Party Democratically Elected? – Mythbusting Berlin

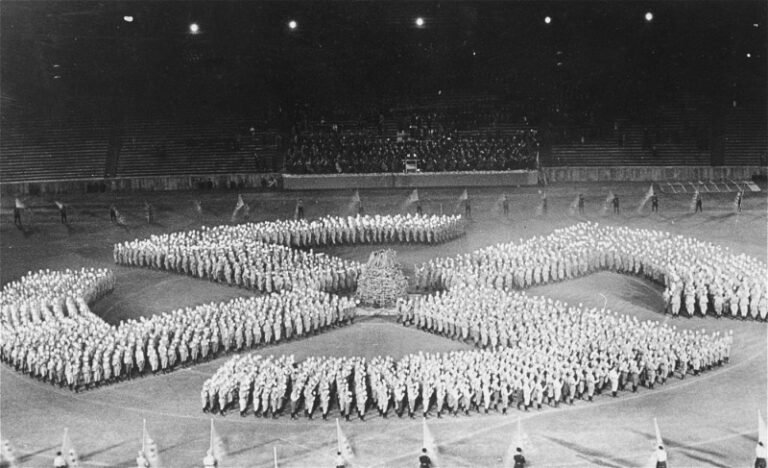

The myth persists that Adolf Hitler rose to power through popular democratic choice. Yet history reveals a darker, more complicated truth. Hitler’s ascent involved exploiting democratic institutions, orchestrating violence, propaganda, and political intrigue—not a simple election victory. Understanding how Germany’s democracy collapsed into dictatorship helps illuminate the dangerous interplay between public desperation, elite miscalculations, and extremist ambition, providing crucial lessons for safeguarding democracy today.

Were The Allied Bombings Of Germany War Crimes? – Mythbusting Berlin

The history of the Allied bombing of Germany during the Second World War still triggers fierce debate. Was reducing cities to rubble a necessary evil – justice from above in a just war – or an unforgivable crime? Can the intentional targeting of civilians ever be justified as militarily necessary?

In a conflict where all rules seemed to vanish, an even more pertinent question persists: by the very standards they would use to judge their

Were The Nazi Medical Experiments Useful? – Mythbusting Berlin

Before the Nazi period, German medicine was considered the envy of the world – a shining monument to progress. But deep within that monument, a rot was spreading, one which would collapse the entire structure into an abattoir. From the wreckage, we are left with a profoundly uncomfortable inheritance: a moral enigma wrapped in doctor’s whites.

What to make of the data, the images, and the terrible knowledge gleaned from unimaginable human suffering. Whether

What Are The Origins Of The Nazi Salute? – Mythbusting Berlin

A specter is haunting the modern mind, a gesture so charged with the dark electricity of history that its mere depiction can unleash a storm of controversy.

It is a simple movement: the right arm, stiff and straight, raised to the sky. But in that simplicity lies a terrifying power, a symbol of a regime that plunged the world into an abyss and a chilling reminder of humanity’s capacity for organised hatred.

This

What Are The Origins Of The Nazi Swastika? – Mythbusting Berlin

Long before the legions of the Third Reich marched beneath its stark, unnerving geometry, the swastika lived a thousand different lives. It was a symbol of breathtaking antiquity, a globetrotting emblem of hope and good fortune that found a home in the most disparate of cultures. To even begin to understand its dark 20th-century incarnation, one must first journey back, not centuries, but millennia.

What Are The Pink Pipes In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

A first-time visitor to Berlin could be forgiven for thinking the city is in the midst of a bizarre art installation. Bright pink pipes, thick as an elephant’s leg, climb out of the ground, snake over pavements, arch across roads, and disappear back into the earth. Are they part of a complex gas network? A postmodern artistic statement? A whimsical navigation system? These theories, all logical, are all wrong. The truth is far more elemental,

What Do The Colours Of The German Flag Symbolise? – Mythbusting Berlin

What does a flag mean? Is it merely a coloured cloth, or does it hold the hopes, struggles, and identity of a nation? The German flag, with its bold stripes of black, red, and gold, is instantly recognisable. But the story of its colours is a tumultuous journey through revolution, suppression, and reinvention. The common explanation for their symbolism is a simple, romantic verse, yet the truth is a far more complex and contested tale,

What Happened To Adolf Hitler’s Alligator? – Mythbusting Berlin

It is often said that you can tell a lot about a person by their relationship with animals; that owners often come to look and behave like their pets. Or is it perhaps more that people choose their pets to correspond to their personality? Nazi leader Adolf Hitler’s love of dogs, for example, is well documented but what is there to make of his relationship with reptiles?

What Happenened To The German Royal Family? – Mythbusting Berlin

When the smoke cleared over the trenches in November 1918, the German Empire had evaporated, and with it, the divine right of the Hohenzollern dynasty. Conventional wisdom suggests the family simply vanished into the sepia-toned obscurity of history books—exiled, forgotten, and irrelevant. But dynasties, like weeds in a landscaped garden, are notoriously difficult to uproot entirely. The story of the German royals did not end with the Kaiser’s flight to Holland; it merely shifted gears.

What Is The Difference Between Fascism & Nazism? – Mythbusting Berlin

While the terms ‘Fascist’ and ‘Nazi’ are often bandied around interchangeably as shorthand for tyranny – Italian fascism and German National Socialism were distinctly different beasts. Albeit ideological kin. One an ideology of state-worship, born from post-war chaos and national pride; the other built upon a fanatical, pseudo-scientific obsession with race. Two peas in the same totalitarian pod – twins in tyranny – more succinctly summarised as the Nazi chicken to the Fascist egg.

What Was Checkpoint Charlie? – Mythbusting Berlin

Checkpoint Charlie remains among Berlin’s most visited historical sites, famed worldwide for its significance during the Cold War. Originally established as a modest border-crossing point, it evolved dramatically over the decades into an international symbol of freedom, espionage, and intrigue. Today, critics and locals often dismiss it as little more than a tourist trap—Berlin’s Disneyland—but how exactly did Checkpoint Charlie get its peculiar name, and what truths hide behind its popularity?

What Was Prussia? – Mythbusting Berlin

Prussia’s legacy is both remarkable and contentious—once a minor duchy, it rose dramatically to shape modern European history. Renowned for military discipline, administrative efficiency, and cultural sophistication, Prussia was instrumental in uniting the German states, laying foundations for a unified Germany. But how did this kingdom, with its roots in Baltic territories, achieve such prominence, and why does its complex history continue to evoke admiration, debate, and occasional discomfort in Germany today?

What Was The Berlin Airlift? – Mythbusting Berlin

In the ruins of 1948, the silence of Berlin was not a sign of peace, but a held breath before a new catastrophe. The city, drowning in rubble and political intrigue, became the staging ground for the twentieth century’s most audacious gamble. While popular history remembers the chocolate parachutes and smiling pilots, the reality of the Berlin Airlift was a terrifying operational nightmare born from a ruthless currency war. It wasn’t just a humanitarian mission;

What Was The Socialist Kiss? – Mythbusting Berlin

It is one of the most curious and enduring images of the Cold War: two middle-aged, grey-suited men, locked in a fervent embrace, their lips pressed together in a kiss of apparent revolutionary passion. This was the ‘Socialist Fraternal Kiss’, a ritual that, for a time, seemed to encapsulate the unwavering solidarity of the Eastern Bloc.

But what was behind this seemingly intimate gesture? Was it a genuine expression of camaraderie, a piece of

Who Built The Berlin Wall? – Mythbusting Berlin

One of the most common questions I have encountered from people curious about Berlin, and often so cryptically phrased. Who built the Berlin Wall? A simple five-word query, yet one that can be read one of two ways. More than thirty years since the ‘Fall of the Wall’, the story of its construction continues to baffle many who are mainly familiar with its existence through knowledge of its importance…

Who Really Raised The Soviet Flag On The Reichstag? – Mythbusting Berlin

One iconic photograph has come to symbolise the Red Army’s victory over Nazi Germany in 1945—the Soviet flag waving triumphantly above Berlin’s battered Reichstag building. Yet behind this enduring image lies controversy, confusion, and political manipulation. Who truly raised the Soviet banner atop the Reichstag? Was it a spontaneous act of heroism or carefully staged Soviet propaganda? Decades later, unraveling the truth reveals surprising layers beneath the mythologized symbol of Soviet triumph.

Who Was Really Responsible For The Reichstag Fire? – Mythbusting Berlin

Various theories have been posited as to who actually set fire to the German parliament in 1933. Was it the opening act in an attempted Communist coup or a calculated false flag operation carried out by elements of the Nazi Party, intended to create the conditions necessary for introducing single-party rule? And what part did the young man from Holland, arrested shirtless inside the building the night of the fire, play in this event?

Who Were The Last Nazis On Trial? – Mythbusting Berlin

More than eighty years after the Holocaust, courtrooms across Germany still echo with testimony from the final chapter of Nazi justice. Centenarian defendants in wheelchairs, their faces hidden behind folders, arrive to answer for crimes committed in their youth. These are not the architects of genocide—those men faced their reckoning at Nuremberg decades ago. These are the guards, the secretaries, the bookkeepers: ordinary people who enabled extraordinary evil. Their trials represent a legal revolution: the

Why Is Berlin The Capital Of Germany? – Mythbusting Berlin

There was little in its humble origins—as a twin trading outpost on a minor European river—to suggest that Berlin was destined for greatness. It sits on the flat expanse of the North European Plain, a landscape once dismissively referred to as the “sandbox of the Holy Roman Empire.” Unlike other world capitals, it lacks breathtaking scenery or a naturally defensible position. It is a city built not on majestic hills or a grand harbour, but