Early in the morning of April 20th, Hermann Göring would leave his Carinhall residence north of Berlin for the final time.

The Schorfheide forest surrounding the estate had served as a hunting area for nobility for centuries; although now the tranquillity of this pine and oak woodland populated by red deer and wild boar was being disrupted by the distant rumble of artillery – as Soviet Marshal Konstantin Rokossovsky’s 2nd Belorussian Front drew nearer.

Known to most as the Supreme Commander of the once formidable Nazi Air Force, Göring also possessed many other titles – as the Reichsminister of Forestry, Minister-President of the Free State of Prussia, and Reich Plenipotentiary of the Four Year Plan.

As such he also held a certain predilection for lavishness and had constructed his country residence of Carinhall, named after his first wife, on the grounds of this large hunting estate – as a veritable vanity project. Werner March, the architect responsible for the Olympic Stadium in Berlin, had been enlisted to ensure the scale of this monumental residence would reflect a man of Göring’s calibre and aspirations.

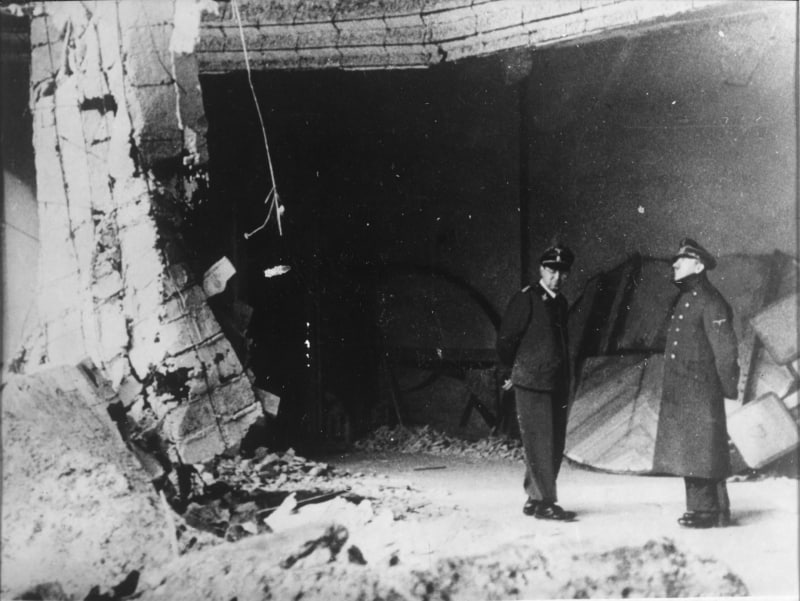

On the morning of April 20th, though, Göring hit a detonator switch and triggered a series of explosions that would force Carinhall to collapse in on itself. Rather than let his compound fall into the hands of the advancing Soviets, he had enlisted a Luftwaffe demolitions team to prepare the property to be ruined.

Insisting on blowing the place up himself.

Speeding out through the large entrance gates – one of the few sections of the property that remain standing to this day – Göring’s limousine would head towards Berlin and the New Reich Chancellery – to congratulate Adolf Hitler on his 56th birthday.

A convoy of trucks would also leave Carinhall but head further south – their cargo, much of the looted treasure that Göring had acquired over his lucrative career.

The preservation of artwork and antiquities was high on the Nazi agenda – and especially Göring’s – even at such a late stage in the war. Two day later, Adolf Hitler would issue an executive directive stating that despite his scorched earth policy instituted on March 19th – the so-called Nero Decree – denying Allied or Soviet forces access to infrastructure, transportation, or communications on German soil that the destruction of works of art would be categorically forbidden.

Of course, the Luftwaffe vehicles used to transport the Reichsmarshal’s collection could very well have served a more patriotic purpose at the front.

Berlin’s extensive array of antiquities had already been shuffled off into storage at various stages of the war – with the coin collection from the Kaiser Wilhelm museum, the bust of Nefertiti, and even the disassembled Pergamon Altar all gathered together inside a mammoth flak tower in West Berlin. Along with thousands of Greek vases, paintings by Degas, Monet, and Renoir, and nine thousand antique gems.

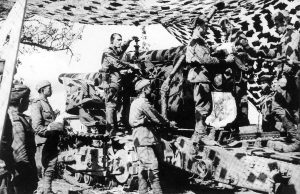

The ‘Zoo Flak tower’ was one of three pairs of concrete air defense bunkers built across Berlin between 1940 and 1942 – the others located in the Volkspark Friedrichshain and Volkspark Humboldthain. A planned fourth tower at Tempelhof Airport was never built as the airport was already equipped with substantial anti-aircraft equipment.

These bunkers would not only be used to counter air attacks on the city and preserve artworks (in the case of the Zoo Flakturm), but also as civilian air raid shelters.

And in the final stages of the Battle of Berlin – as the front crept closer – the combat batteries would participate in the defence of the city.

Despite the imposing size of these bunkers – Berlin’s defences in April 1945 did not seem to offer much reassurance to its millions of inhabitants. As a joke popular at the time would indicate: “It will take the Reds two hours and fifteen minutes to break through. Two hours laughing their heads off and fifteen minutes smashing the barricades.”

Passing through the city on his way to an assignment in Italy at the start of April was disgraced General Max Pemsel, who had been Chief of Staff of the Seventh Army defending Normandy on D-Day. Considered an expert on fortifications, he would describe the effort in Berlin as “utterly futile, ridiculous!”

As the city braced for the arrival of the Red Army, squads of men, boys, prisoners of war, and foreign labourers were scattered across Berlin still preparing eleventh hour defences. Makeshift fortifications dotted the city; upturned buses, trams, piles of rubble from wrecked buildings, and tank turrets buried in the streets to provide fixed firing positions.

Some in the city were still holding out on the hope that American or British forces might cross the Elbe and make it to Berlin before the Soviets.

On April 20th 1945, Fritz Kraft, director of the municipal subway system, was given instructions by Berlin’s mayor to prepare for the arrival of the Allies: “If the Western Allies arrive here first, hand them over intact. If the Soviets arrive, destroy as much as possible.” A similar order would be sent to personnel staffing the telephone exchanges throughout the city, although with no clear instructions of how exactly to wreck the exchanges not a single one was destroyed.

Almost all of them would continue to work throughout the Battle of Berlin.

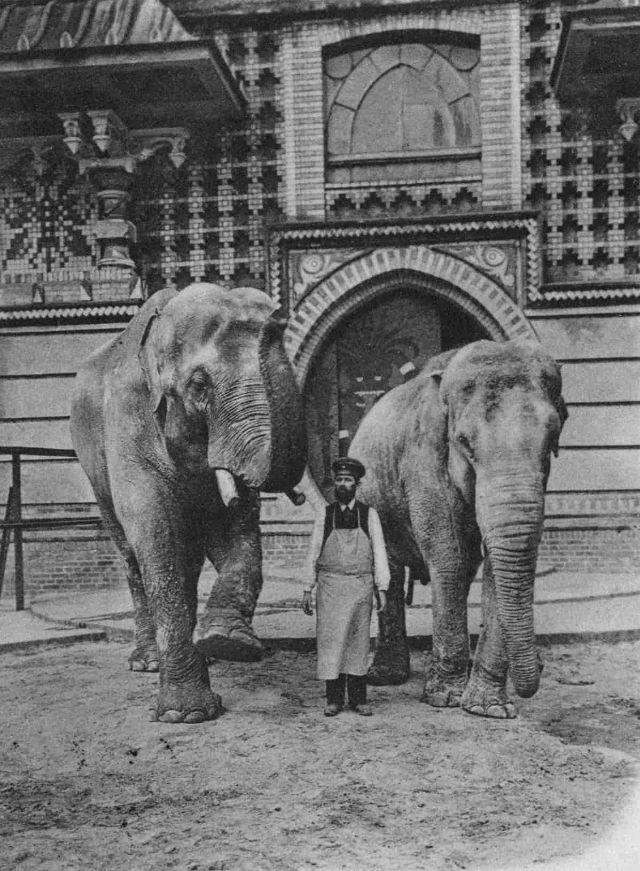

One of the few welcome respites in the city from the chaos of rationing, Allied air raids, and defensive preparations was the city’s Zoologischer Garten. Opened in 1844 as the first zoo in Germany, in April 1945 it stood half destroyed, with many of the animals starving.

Electricity in the Zoo stopped at 10:50am on April 20th, making it impossible to pump water.

Later the same day, the Zoo would finally close its gates from the rest of the war.

Zoo director, Lutz Heck, struggled to face the reality of the situation. Knowing that it would be only a matter of time before the animals would start to die – concluded that the dangerous animals would have to be destroyed. Including the Zoo’s prize baboon. In need of space to think, Heck took one of the zoo keepers fishing in the nearby Landwehr Canal.

Where the men caught two pike.

Although few Berliners would remember Adolf Hitler’s 56th birthday for the blustering tribute that Propaganda Minister, Joseph Goebbels, had broadcast over the radio the previous evening, referring to the Nazi leader as the ‘Man of the Century’ – many would later recall the extra rations they received on April 20th and the fine ‘Führer weather’ – the fourth fine day in a row.

As Nazi flags were raised across the city on ruined buildings, ‘crisis rations’ were handed out to the hungry populace, with the women of the city – who vastly outnumbered the men present – queuing throughout the day. Extra bacon or sausage, rice, lentils, peas or beans, sugar, coffee, and some fats. All to last eight days.

Whether Berliners realised it or not, the city was officially a battlefield.

On the morning of April 20th, Adolf Hitler had ordered the execution of Operation Clausewitz – a comprehensive 33 page plan describing how Berlin was to be transformed into a frontline city, dividing the capital into active defensive zones. A single sentence summarised the gravity of the situation:

“The Reich capital will be defended to the last man and to the last bullet.”

By the end of the day collection points would be established for drafting new recruits and pulling together the shell shocked and exhausted German Army stragglers from the streets. Barracks and local sports fields would be used to gather and organise Alarm units of young boys, who would be promptly issued rifles and oversized steel helmets.

At 11:30am, Soviet long-range artillery of the 3rd Shock and 47th Armies had begun bombarding the city’s outskirts, not leaving much time between the end of the Allied air raid from the previous night for the dust to settle. And the beleaguered city’s fire service to deal with the aftermath.

Hitler had been awoken more than two hours earlier, at 9am, in his room in the Führerbunker, to be debriefed on the situation at the front – that the Soviet troops that had broken the line between Guben and Forst were now hurtling towards the capital. Marshal Zhukov’s 47th Army was descending on Bernau, and the 3rd Shock Army was expected to be within the Berlin suburb of Weissenssee within 24 hours.

Faced with this disastrous news, the Nazi leader would return to bed – before waking again to play with his dog, Wolf, then proceeding to a honorary birthday gathering in the New Reich Chancellery with officers of Army Group Centre and Nazi Party functionaries.

Hermann Göring would not be the only member of Hitler’s inner circle to gather at the Chancellery on April 20th 1945.

For many who would gather it would be the last time they would see their beloved Führer alive.

SS leader Heinrich Himmler would make an appearance, as would Propaganda Minister, Joseph Goebbels. Hitler’s star architect, Albert Speer – now Minister of Armaments – would pay his respects alongside Foreign Minister, Joachim von Ribbentrop, Chief of the Nazi Party Chancellery Martin Bormann and military leaders Karl Dönitz, Wilhelm Keitel, and Alfred Jodl.

Of all the men gathered to pledge allegiance to their Führer, trooping through the great polished marble rooms of the New Reich Chancellery, the two closest to the Nazi leader – and considered most loyal – were already planning their separate fates.

The previous evening, Heinrich Himmler had arranged meetings with Count Folke Bernadotte of the Red Cross and Norbert Masur of the World Jewish Congress to discuss a release of prisoners held in Nazi camps – but also to establish a line of communication with the Western Allies for potential peace talks. Should the circumstances arise where Himmler would find himself in power and be in a position to negotiate with the British and Americans.

Göring’s fleet of twenty four trucks full of looted goods were already on the road from Carinhall, heading away from the doomed capital to safety. Nazi Germany’s Supreme Commander of the Luftwaffe – who had arrived at Hitler’s birthday gathering wearing khaki ‘like an American general’ – would also head south to his estate in Obersalzburg. Claiming that from there he would organise resistance in Bavaria.

Unlike the dwindling close circle around him, that was spreading out across what remaining of Germany under Nazi control – on various contrived matters of ‘official business’ – Hitler would state he could not expect his troops to fight the decisive battle for Berlin if he removed himself to safety.

With British forces on the Luneburg Heath, heading towards Hamburg – the US Army on the middle Elbe – and the Red Army already occupying Vienna, the main question facing Hitler was where else was left to run. Despite the insistence of members of his entourage that he should flee to Bavaria – and join Göring to lead the final battle there – Hitler looked set to remain in Berlin.

Although he had not yet made his intentions entirely clear.

That afternoon, he would make his last public appearance, in the gardens of the Reich Chancellery, above the Führerbunker, to present medals to young boys of the Hitler Youth. Some of whom would receive Iron Crosses for attacking Soviet tanks. With his left arm hidden behind his back – and suffering from an uncontrollable tremor – Hitler was largely unable to present the medals himself, instead moving along the line of children and cupping a cheek or tweaking an ear in a disturbing final hour gesture.

Hitler Youth leader, Artur Axmann, would stand nearby and watch, later saying that he was: “shocked at the Führer’s appearance. He walked with a stoop. His hands trembled. But it was surprising how much power and determination still radiated from this man.”

After a similar ceremony with SS fighters, Hitler attended an afternoon briefing on the military situation. His advisors would be clear in their assessment:

- Berlin will be surrounded in a matter of days, perhaps hours.

- Busse’s 9th Army will be encircled and destroyed if not allowed to withdraw immediately.

- The Führer and government ministries should be urgently evacuated.

While government departments would be given permission to leave, Hitler would double down on his desire to stay and fight. According to Luftwaffe adjutant Nicolaus von Below: “Hitler stated the battle for Berlin presented the only chance to prevent total defeat.”

One point of protocol would be reaffirmed on April 20th, the implementation of a directive made five days earlier that should the Reich be divided and Hitler become incapable of leading from Berlin – that Admiral Dönitz should take control in the north, and Field Marshal Albert Kesselring in the south.

Meanwhile, in the chaos of the fighting on the eastern front, amidst the disintegration of his forces and loss of communications, General Helmuth Weidling – the recently promoted commander of the LVI Panzer Corps – was conducting a fighting withdrawal towards the capital. His Panzer Corps thoroughly battered and trying to stave off encirclement from Zhukov’s 1st Belorussian Front.

Assessing the damage inflicted by Zhukov’s tankers on April 20th 1945, the war diary of German Army Group Vistula for the day would read: First Guards Tank Army “pierced our front in the area of the Autobahn Frankfurt-Berlin and the road Küstrin-Berlin.” While the Second Guards Tank Army “succeeded in tearing up the forces of the LVI Panzer Corps and CI Corps and in breaking through the outer defense area of Greater Berlin.”

As a result of this chaos, on the evening of April 20th, around 8pm, Weidling lost contact with army high command.

In one of the strangest reversals of the battle of Berlin, the commander of the LVI Panzer Corps would be appointed commander of the Berlin Defence Area three days later – but not before being condemned to death as a deserter.

Hitler retired to bed much earlier than usual on April 20th, leaving his mistress Eva Braun to arrange an impromptu party in the Reich Chancellery, taking Martin Bormann and Hitler’s doctor, Theodor Morell, with her. As they drank champagne and danced, the only record available would play on repeat: ‘Blood Red Roses’ by Max Mensing.

By nightfall, Ivan Konev was worried that his 1st Ukrainian Front was falling behind and that his earlier drive towards Berlin was being threatened now Zhukov’s 1st Belorussian Front further north had gathered momentum. Looking down at a map to study the positions of his forces, he ordered the commanders of the Third and Fourth Guards Tank Army to drive on at even greater speed, cutting through the lines and leaving their flanks exposed.

In a bold, but extremely dangerous move, the Fourth Guards Tank Army would cover 28 miles in less than 24 hours – the Third Guards Tank Army would penetrate even deeper. Pushing 38 miles to the outskirts of Zossen – and the headquarters of the German Army High Command.

To elements of the 1st Ukrainian Front, Berlin was now only twenty-five miles away.

Like the previous four nights, Royal Air Force Mosquitos returned to Berlin to conduct an air raid throughout the night of April 20th – the last RAF raid of the war on the city.

At 2:14am on April 21st Mosquito XVI ML929, of No 109 Squadron, with Flying Officer AC Austin, pilot, and Flying Officer P Moorhead, navigator, claimed the last bombs – four 500-pounders.

**

Our Related Tours

Want to learn more about the Battle of Berlin? Check out our Battle of Berlin tours to explore what remains of this important urban battlefield.

To learn more about the history of Nazi Germany and life in Hitler’s Third Reich, have a look at our Capital Of Tyranny tours.

Bibliography

Beevor, Antony (2003) Berlin: The Downfall 1945 | ISBN 978-0-14-028696-0

Hamilton, Aaron Stephan (2020) Bloody Streets: The Soviet Assault On Berlin | ISBN-13 : 978-1912866137

Kershaw, Ian (2001) Hitler, 1936–1945: Nemesis | ISBN 0-393-04994-9

Le Tissier, Tony (2010) Race for the Reichstag: the 1945 Battle for Berlin | ISBN: 978-1848842304

Le Tissier, Tony(2019) SS Charlemagne: The 33rd Waffen-Grenadier Division of the SS | ISBN: 978-1526756640

Mayo, Jonathan (2016) Hitler’s Last Day: Minute by Minute | ISBN: 978-1780722337

McCormack, David (2017) The Berlin 1945 Battlefield Guide Part I the Battle of the Oder-Neisse | ISBN: 978-1781556078

McCormack, David (2019) The Berlin 1945 Battlefield Guide Part II The Battle of Berlin | ISBN: 978-1781557396

Moorhouse, Roger (2010) Berlin at War | ISBN: 978-0465028559

Ryan, Cornelius (1966) The Last Battle | ISBN 978-0-671-40640-0

Sandner, Harald (2019) Hitler – Das Itinerar, Band IV (Taschenbuch): Aufenthaltsorte und Reisen von 1889 bis 1945 – Band IV: 1940 bis 1945 | ISBN: 978-3957231581

Shirer, William L. The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich | ISBN 978-1451651683.