At 9:30am on April 21st 1945, Adolf Hitler was awakened in the damp concrete Führerbunker by news that Soviet artillery was now pounding Berlin’s central Mitte district.

The Nazi leader immediately ordered the air force to silence the guns. A task the now crippled Luftwaffe was far from capable of performing.

Instead the bombardment would only worsen. With the nearby Hotel Adlon – once the city’s grandest establishment – turned into a military hospital to accommodate the mounting casualties in the area.

An observation post at the Berlin Zoo was however able to pinpoint the volleys as originating from the suburb of Marzahn – no further than 8 miles away from Hitler’s chancellery.

Over the next eleven days, Soviet artillery would unleash hell on the Nazi capital. For a city more than accustomed to the routine – and devastating – air attacks carried out by Anglo-American forces – the introduction of desultory Red Army barrages would bring with it a new and more sinister measure of torment – as more than 1.8 million shells rained down on the city. Almost exceeding, in less than two weeks, the total tonnage of explosives dropped by the British and Americans over the past five years.

Unlike aerial bombing, Soviet artillery would arrive without warning – indiscriminately hitting Alexanderplatz and the Tiergarten throughout the day.

The same morning, senior Nazi party officials would swarm the army headquarters for the Defence of Berlin – located on Hohenzollerndamm – to be granted passes entitling them to leave the beleaguered city. This exodus of armchair warriors – dubbed the ‘Flight of the Golden Pheasants’ by locals – would see the army issue 2,000 exceptions to the citywide policy that all capable of fighting against the Bolshevik enemy should stand their ground. “The rats are leaving the sinking ship,” a colonel on the Chief of Staff would retort. The very same party men who had rallied against the army for cowardice when it suffered losses at the front were now leaving the Nazi capital at the height of its hour of need.

Further north of Berlin an exodus of a much different kind was also taking place on April 21st – having begun the previous day – as around thirty thousand prisoners from the Sachsenhausen Concentration Camp in Oranienburg were death marched west and away from the Soviet advance. Columns of inmates, weakened by their internment in the camp, trailing through northern Brandenburg and Mecklenburg.

Established in 1936, in the shadow of the Summer Olympics, Sachsenhausen served as the nucleus of the concentration camp industry of the Third Reich and a prototype for the other camps that would follow its construction. Run by Heinrich Himmler’s SS, the Nazi party’s ideological warriors, as a proving ground for the brutality and industrial killing that would largely take place further east in places like Auschwitz and the other Operation Reinhard camps.

As these prisoners filed out of the camp and were marched westwards, unaware of their actual destination, many would fall by the roadside – either to be shot by their guards, beaten to death, or left to expire. The corpses of these so-called political enemies of National Socialism littering the countryside in this tragic finale to one of the darkest chapters in German history. Those who might make it to further west alive were possibly to be loaded on boats and barges and taken out to sea to drown, with survivors summarily executed – as to ensure that no evidence would remain of the wickedness these men, women, and children had endured.

Although the Geneva Convention stipulates that prisoners should be moved away from danger, such as an advancing front, the forcible relocation of the prisoners from Sachsenhausen – as with the other Nazi camps – was simply another means of exhausting and ensuring the deaths of these unfortunate souls.

Covering between 20 and 40 kilometres per day, in cold wet weather, through the columns of military vehicles and refugees – and sleeping outside when given time to rest – the Sachsenhausen death marches would travel via Neuruppin or Rheinsberg looking to thread through the British and Soviet front lines. The survivors finally rescued between May 3rd and May 6th, 1945, by soldiers of the 2nd Belorussian Front in Crivitz and Raben-Steinfeld near Schwerin and by American troops of the 7th U.S. Tank Division, near Ludwigslust.

Meanwhile on April 21st, south of Berlin, in one of the last successful German tactical victories on the Eastern Front – the city of Bautzen was attacked by the forces of Army Group Centre. Taking advantage of a gap in the lines made by the rapid advance of Ivan Konev’s 1st Ukrainian Front pushing towards Dresden.

Konev’s force was spread out across a wide area and with supply lines stretched. The German 4th Panzer Army sought to take advantage of this and break through to Berlin while also relieving the 9th Army in its withdrawal from the Seelow Heights.

As elsewhere, the German forces were a mixed collection of experienced fighters, Hitler Youth, and older Volkssturm men. Opposed mainly by the Polish Communist 2nd Army, the German 4th Army inflicted heavy losses on the Soviet forces and managed to recapture Bautzen.

Though they would not make it to Berlin as a relief force.

Back in the city, around 3,000 Hitler Youth were assembled at the Olympic Stadium to confront the advancing Soviets. Volkssturm troops would eventually join the defense of the Reichssportfeld site, armed with Italian ammunition for their German rifles. As was the case for many of the would be defenders of the city, wearing mismatched uniforms and often carrying whatever weapons were at hand. As Hitler’s Third Reich convulsed in its dying throes, the words the Nazi leader had announced years earlier took on new meaning: “Each mother who gives birth to a child has struck a blow for the future of our people.”

A future that look more and more uncertain – with young cannon fodder and invalid old men used as kindling for the bonfire the Soviet would soon light in the Nazi capital.

Not classified as part of the regular army, the Hitler Youth and Volkssturm units were controlled by the Nazi Party, and would often fight alongside units from the SS – or man barricades setup throughout Berlin. Armed with panzerfaust anti-tank launchers, that many had been trained to use only earlier in the month – at a mass gathering on the Reichssportfeld – if at all.

The spectre of Hitler’s wonder weapons, spread with propaganda slogans such as Die Vergeltung Kommt (Revenge is coming!) hung over the city. As did the belief that relief would come in the form of reinforcements from elsewhere. Rumours of rifts in the Allied coalition – between Stalin and the West – or US airborne troops parachuting into the city would spread through Berlin.

None of which would materialise.

The reality would be much more terrible.

Perhaps most indicative of the verisimilitude of the Nazi bluster of the period was the Volksgranate 45 (the people’s hand grenade) that Volkssturm men would be issued in April 1945. A simple lump of concrete wrapped in a concrete charge that was more likely to maim or kill the thrower than the target.

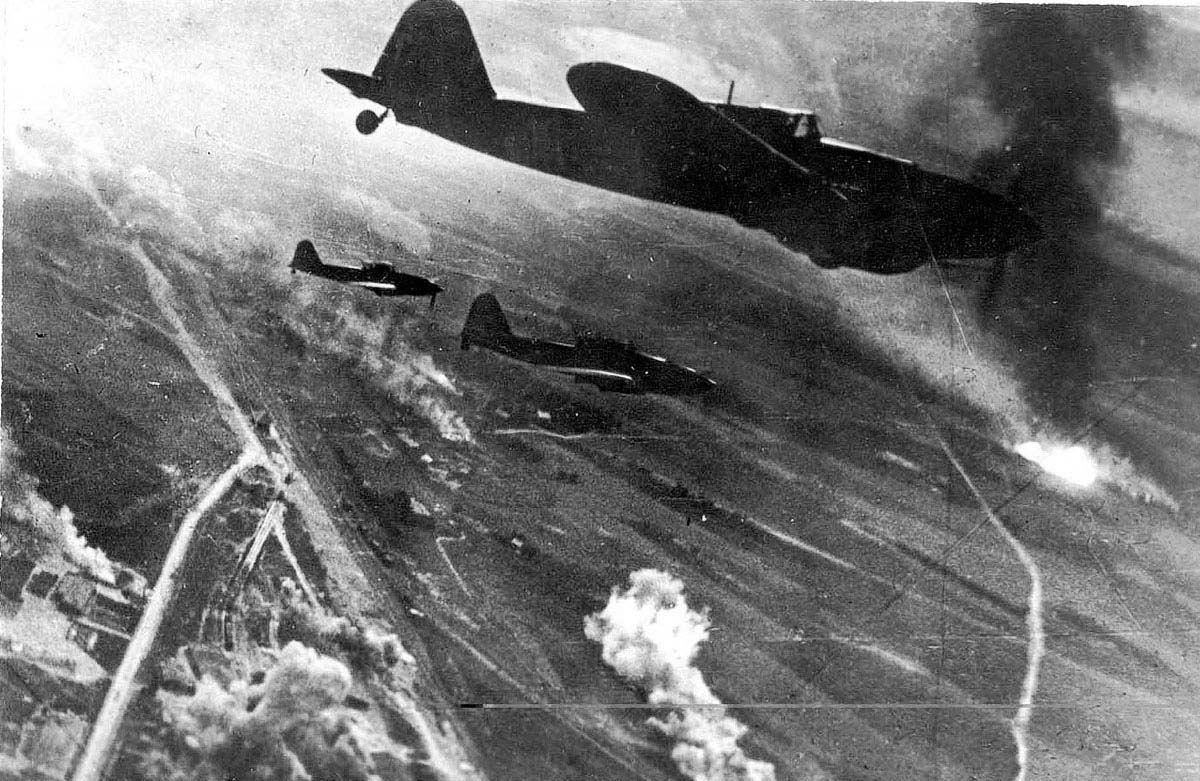

On April 21st, remnants of the German 9th Army’s central force, and specifically General Weidling’s 56th Panzer Corps, were busy being pushed back towards the capital across the eastern side of the Berlin autobahn ring road. Weidling’s troops withdrew into Berlin’s suburbs after holding a line between Mahlsdorf and Woltersdorf. Through barricades manned by Volkssturm men that would collapse like balsa wood in the face of the Soviet onslaught and past bodies hanging from trees – victims of roadside executions for desertion. The Red Army’s Sturmovik air-to-ground assault planes strafing the convoys of soldiers who were now streaming back to the capital, leaving corpses to be pushed aside and piled against the side of the road.

Hero of the Soviet Union Colonel V. Belousov, in command of a group of Sturmovick fighters of the Sixteenth Air Army reported:

“All day long until it was dark, more and more groups of Ilyushins fought on the battlefield without ceasing, motor vehicles and tanks burned, and enemy infantry was chased through the forests. Anything that survived the air attacks was caught by our tankers and motorized riflemen.”

Zhukov’s 1st Belorussian Front had begun to push south – in an attempt to preempt Marshal Konev’s arrival to Berlin. The 8th Guard Army would be sent towards the river Spree to capture Erkner, just south of Rüdersdorf, on April 21st. Still bound to encircle the city on the northern flank, Zhukov’s 47th Army was dispatched to Spandau, while the 2nd Guards Tank Army headed to Oranienburg. The 1st Mechanized Corps captured Bernau bei Berlin against little, if any, resistance. The 37th Mechanized Brigade would reach the outskirts of Buch by late morning and advance into the town before proceeding to Karow and liberating some 2,000 Soviet and Polish girls from a labour camp.

On April 21st – elements of the 5th Shock Army would reach the eastern Berlin suburb of Marzahn – signalling the arrival of the Red Army in the city.

A single storey building on Landsberger Allee (no. 563) – occupied by a vegetable gardener named Gustav Frick in 1945 – stands today as a memorial to the arrival of Soviet troops. Although debate continues as to whether it was actually Marzahn or the borough of Malchow – in Berlin Lichtenberg – where the Red Army first set foot in Berlin.

What is clear is that having spent the last two days crossing open countryside, Soviet armour was still advancing rapidly, with infantry arriving behind to mop up any remaining pockets of German resistance. Ensuring a swift arch across the north of the city and into Berlin’s outskirts.

But the denser the urban terrain, the more difficult tactical operations would become for the Soviet troops.

To the south of Berlin, Ivan Konev’s 1st Ukrainian Front was threatening to take Zossen and capture the German Army High Command.

At 9am, a senior German officer at the headquarters had received a telephone call alerting him that Soviet forces had been spotted in the vicinity – with forty Soviet tanks coming up the road from Baruth to Zossen. By 11am, the German army staff at Zossen were made aware that a reconnaissance detachment sent to investigate had been attacked and suffered heavy casualties. And that despite the proximity of Konev’s troops, Hitler was adamant that the general staff remain in place.

With the compound about to be overrun imminently, the officers of the general staff instinctively continued their briefing – only to hear the distant gunfire fall silent. The Soviet tanks had come to a halt on the Baruth road after running out of diesel.

Soon the order came from the Reich Chancellery in Berlin that the headquarters should be relocated to Eiche near Potsdam and a tank base at Krampnitz. Non-essential staff would be sent to the south of the country.

As this large convoy of vehicles left to head to join the forces in Bavaria, it was hit by one of the last Luftwaffe sorties of the war, after being misidentified as Soviet.

Later in the afternoon, Red Army soldiers would arrive in the Zossen compound to find the caretaker waiting and offering to take them on a guided tour. Only four troops were left at the headquarters, three would surrender immediately, while the fourth was too drunk to do so.

As the German Army Staff were relocating from Zossen, a rumour was starting to spread that General Weidling – the head of the 56th Panzer Corps who was busy struggled against Zhukov’s forces on the Oder front had moved his headquarters to Döberitz, just north of Potsdam – and on the wrong side of the city.

Meanwhile in the Führerbunker, Hitler was now struggling to find a solution to shore up the crumbling front and launch an offensive against the Soviets. Raging against the incompetence of the air force to mount an attack, regardless of having few serviceable aircraft and even less aviation fuel, Hitler instead found the relief he was looking for in the form of an SS group – the III SS Germanische Corps – commanded by Obergruppenführer Felix Steiner. From their positions in the Eberswalde, Steiner’s men were to attack against the right flank of the 1st Belorussian Front, heading south to cut off the Russians drive on Berlin. With this he would reestablish a connection between Von Manteuffel’s Third Panzer Army in the north and the 9th Army that had days earlier experienced its Seelow Heights position crumble and was fighting in the open country east of Berlin.

Calling Steiner, Hitler would say: “Every available man between Berlin and the Baltic Sea up to Stettin and Hamburg is to be drawn into this attack I have ordered.” Later adding: “You will see, Steiner. You will see. The Russians will suffer their greatest defeat before the gates of Berlin.”

At threat of execution for desertion, Steiner was now designated as the relief force for Berlin. Among the many reasons why his plan would not succeed was the simple matter that Steiner just did not have the men. Steiner was meant to have gathered into his group the men from the 9th Army that had been pushed north by Zhukov’s drive to Berlin. But in the chaos, it had been impossible to find the forces.

Yet his name remained on Hitler’s map – and a small flag noting Group Steiner to be moved around the table.

The Nazi leader would also decide on the evening of April 21st to sack the commander of Berlin, General Reymann. Two replacements were considered then rejected until Hitler settled on a Colonel named Käther – chief National Socialist Führungsoffizier. He would be promoted to major general and then lieutenant general before his appointment was cancelled the next day.

Leaving the Berlin Defense Area without a commander just as the Red Army was entering the city.

**

Our Related Tours

Want to learn more about the Battle of Berlin? Check out our Battle of Berlin tours to explore what remains of this important urban battlefield.

To learn more about the history of Nazi Germany and life in Hitler’s Third Reich, have a look at our Capital Of Tyranny tours.

Bibliography

Beevor, Antony (2003) Berlin: The Downfall 1945 | ISBN 978-0-14-028696-0

Hamilton, Aaron Stephan (2020) Bloody Streets: The Soviet Assault On Berlin | ISBN-13 : 978-1912866137

Kershaw, Ian (2001) Hitler, 1936–1945: Nemesis | ISBN 0-393-04994-9

Le Tissier, Tony (2010) Race for the Reichstag: the 1945 Battle for Berlin | ISBN: 978-1848842304

Le Tissier, Tony(2019) SS Charlemagne: The 33rd Waffen-Grenadier Division of the SS | ISBN: 978-1526756640

Mayo, Jonathan (2016) Hitler’s Last Day: Minute by Minute | ISBN: 978-1780722337

McCormack, David (2017) The Berlin 1945 Battlefield Guide Part I the Battle of the Oder-Neisse | ISBN: 978-1781556078

McCormack, David (2019) The Berlin 1945 Battlefield Guide Part II The Battle of Berlin | ISBN: 978-1781557396

Moorhouse, Roger (2010) Berlin at War | ISBN: 978-0465028559

Ryan, Cornelius (1966) The Last Battle | ISBN 978-0-671-40640-0

Sandner, Harald (2019) Hitler – Das Itinerar, Band IV (Taschenbuch): Aufenthaltsorte und Reisen von 1889 bis 1945 – Band IV: 1940 bis 1945 | ISBN: 978-3957231581

Shirer, William L. The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich | ISBN 978-1451651683.