Sunday April 22nd 1945 had been the original date outlined in Stalin’s plans for the fall of Berlin – coinciding with what would have been Vladimir Lenin’s birthday.

The troops of commander Georgy Zhukov’s 1st Belorussian Front, however, were largely still only on the city’s periphery and grinding forwards slowly.

Zhukov had underestimated not only the persistence of the German defenders at the Seelow Heights, that had pushed back his advance by three days, but also the network of streams and canals that crisscrossed the eastern approach to Berlin and the historic territory of the Mark Brandenburg.

Now faced with the task of moving into Berlin, he would command his soldiers to attack in five incisive movements:

- The 8th Guards Army would force German General Weidling’s LVI Panzer Corps back into the city centre

- The 5th Shock Army would push into Berlin’s eastern suburbs

- While the 3rd Shock Army was ordered to advance through the northern part of the city and into the centre

- The 2nd Tanks Guard Army was to flank northwest around Berlin to Charlottenburg on the west side via Siemensstadt

- The 47th Army after moving through Oranienburg was to move even further west to complete the encirclement of the city

While moving into the urban city area, Zhukov was also working to throw a noose around the Nazi capital – restricting movement in and out of the city and denying the defenders any reinforcements.

The spearheads of both the 3rd and 5th Shock Armies, however, would spend much of the day preparing themselves for the street fighting role that was to follow, with artillery shelling the city, but the troops making little effort to push the line forward.

By the end of the day the 1st Belorussian offensive would move into the outskirts of the city, the districts of Weissensee, Pankow, and Lichtenberg in the east. With additional forces crossing the River Havel north of Spandau, while fierce fighting took place in Köpenick throughout the day.

To the south of the city, troops of Ivan Konev’s 1st Ukrainian front were pivoting towards the Teltow Canal near Klein-Machnow to establish the lower half of Zhukov’s noose.

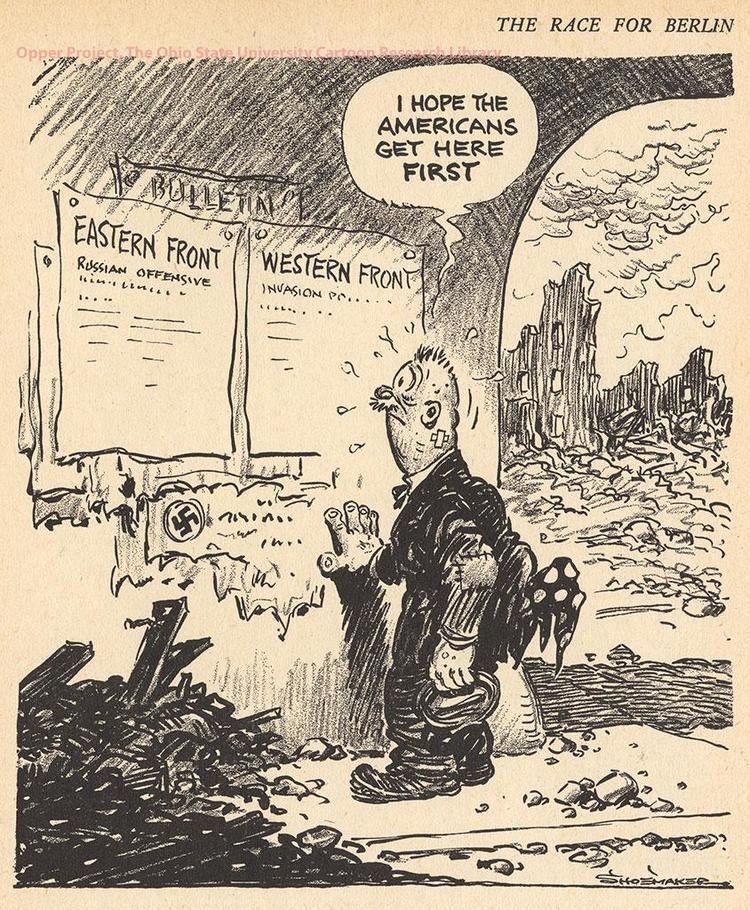

Having travelled nearly three times further than Zhukov’s 1st Belorussian Front, Konev’s 1st Ukrainian Front was now threatening to reach the Red Army’s final objective – the Reichstag – first.

Not only was Zhukov days behind schedule, it was looking more and more likely that his rival, Konev, might usurp him.

Defence of the city was gradually being organised, with the troops withdrawing from their eastern positions slowly reorganising in the capital. Although neither Gotthard Heinrici, head of Army Group Vistula, or General Weidling, head of LVI Panzer Corps were particularly happy about engaging in urban fighting.

Meanwhile, head of SS Nordland – Joachim Ziegler – was planning on moving his troops south of Berlin then towards the Western allies to avoid the city altogether.

The mixed array of retreated Germany army and SS men, elderly Volkssturm, Hitler Youth, and drafted civilians would soon get their first experience of fighting on the streets of Berlin.

Yet the majority of mobilised Volkssturm units still remained outside the city.

Early on April 22nd, the Siemensstadt Volkssturm – composed of eldery factory workers – would have its baptism of fire, at positions it had been preparing for much of the previous two months immediately north of the Kaulsdorf and Mahlsdorf S-bahn stations. Accompanied by a Wehrmacht battalion on their left flank and the ‘Warnholz’ police battalion on their right flank, the unit would have its forward companies attacked by Soviet tanks from nearby Hellesdorf. After carrying out a rather successful counterattack, the men of Volkssturm battalion 3/115th withdrew to new positions near Friedrichsfelde Ost S-bahn station. Although by midnight that position would become untenable and they would pull back even further into the city.

Propaganda Minister, Joseph Goebbels, would publish an editorial in the last edition of Das Reich newspaper calling on every man, woman, and child to fight in defence of the city.

“The hour of our last triumph is awaiting us. It will be bought with blood and tears but it will justify all the sacrifices we have made.” – Joseph Goebbels

For the first time, Berlin’s massive Flak towers would be tasked with engaging ground targets – with the Friedrichshain tower firing 5,000 12.8cm rounds on Red Army tank and infantry formations.

For most of the morning of April 22nd, Adolf Hitler – from his Führerbunker headquarters in Berlin – was feverishly demanding news of the counterattack by SS-Obergruppenführer Felix Steiner and his ghost army further north that the Führer expected would come to relieve the city. After telling Luftwaffe Chief of Staff, General Koller, to send up reconnaissance aircraft, Hitler talked with SS Chief, Heinrich Himmler, and received an optimistic reply that seemed to satisfy him. Although by the midday briefing, it was clear that Steiner’s counterattack was not coming.

Soviet forces had broken the perimeter defensive ring of the city. Dejected and full of rage, Hitler began to scream and yell. Eventually he collapsed into an armchair and wept, saying openly for the first time that the war was lost. And that he would rather kill himself than be captured by the enemy. Putting to rest any belief in the bunker that he might still escape south to Berchtesgaden and organise an ‘Alpine Redoubt’.

On April 21st the Transocean News Agency and the Reichssender Berlin stations fell silent. As the battle for Berlin continued, more and more of the city’s residents would become reliant on foreign news, such as the BBC, for their understanding of the events unfolding. For some time the newspapers in the city had been reduced to single sheet publications, full of party bluster. With the exception of those printed by the Wehrmacht that would sometimes contain reference to villages and towns whereby it was possible to plot out the frontline or guess roughly how far away the Soviet troops were.

Battery powered radios would help make up for the power cuts that were proving better censorship of foreign broadcasts than the Nazi police state previously could.

Word of mouth and the Chinese whispers method of spreading rumours would add to the nightmarish unreality that pervaded the city – as rarely was the news good.

North of Berlin in the sleepy village of Oranienburg, units of the 1st Communist Polish Army and 47th Army – under Soviet command – liberated the Sachsenhausen Concentration Camp on April 22nd. Finding around 3,000 emaciated prisoners as well as nurses and doctors, abandoned by their SS captors who had already fled west in the death marches of the majority of camp prisoners the previous day. Three hundred of the camp’s former inmates would not survive their liberation and subsequently died as a result of their incarceration; they are now buried in six mass graves by the camp wall, near the infirmary.

As the ‘model camp’ built by the SS in 1936, Sachsenhausen was built initially to incarcerate political prisoners. But would also see use as an industrial killing facility, where in 1941 some 13,000 Soviet prisoners of war were murdered in a ‘neck-shot’ (Genickschuss) process.

It is estimated that 200,000 prisoners passed through Sachsenhausen and that 30,000 people were murdered there. Medical experimentation, including castration and sterilisation, would take place within the confines of the camp, and disabled men and women were sent from Sachsenhausen to euthanasia centres to be murdered as undesirables.

Soviet troops had already liberated Auschwitz in January 1945, and even managed to overrun Majdanek in July 1944 – the first Nazi death camp to be liberated. What the Soviets discovered at Sachsenhausen would only add to the horror.

But to many Berliners who would hear the news of the camp’s liberation – only 35km north of the city – the stories of barbarity and inhumanity were largely enemy propaganda.

Adolf Hitler’s breakdown earlier in the day had subsided by the afternoon, following a conversation with Propaganda Minister, Joseph Goebbels – where Goebbel’s informed Hitler of his plan to bring his wife and their six children to join the Führer in the bunker – the Nazi leader emerged to address his entourage and confirmed a new plan. General Wenck’s 12th Army, currently facing the Americans on the Elbe, could be turned around and head towards Berlin. General Field Marshal Keitel would coordinate the movement of the 12th Army to the west and the 9th Army to the east, which was still struggling to break out of its near encirclement. Highlighting the seriousness of the situation, Hitler would now clearly state to his generals his intention to kill himself rather than be captured by the Soviets.

It would be victory – or death.

In striking contrast to any notion of business as usual, life in the Führerbunker was descending into madness, as the walls cracked from the repeated bombing and the dust seeped into the air – making it almost unbearable to breathe, especially for the officers crammed into the tiny conference room. Although the ventilation system still worked well, the men would be almost asleep on their feet, as Hitler was the only one to sit. Food and alcohol were in no short supply, which meant drunkenness was a common sight – regardless of rank.

Later in the evening, Hitler summoned his two secretaries, Gerda Christian and Traudl Junge, along with his Austrian dietitian, Constanze Manzialy, to his sitting room and told the women to prepare to leave to the Berghof in Bavaria with the rest of the staff.

Operation Seraglio, the evacuation to the Berchtesgaden, had already started, with a party preparing to leave the next day. Hitler orders that all personal papers in Berlin, Munich, and Berchtesgaden should immediately be burned. A force of 10 Junkers Ju 52/3m transport aircraft operating from the Berlin-Gatow airfield would shuttle staff to safety in the south of the country, taking with them Hitler’s doctor Morell – who managed to carry an army foot locker of Hitler’s medical records with him.

The women of Hitler’s close circle would, however, refuse to leave him in his final days. Hitler reportedly looked at them fondly and said: “If only my generals had been as brave as you,” before distributing cyanide pills to be used in case of the arrival of the Red Army.

The ‘first lady of the Reich’ – Magda Goebbels – would arrive in the bunker later in the day, bringing with her the six children, ranging from twelve years old down to five: all with names beginning with the letter H. Perhaps a reference to Hitler’s name: Helga, Hilde, Helmut, Holde, Hedda, and Heide. For her loyalty at this desperate time, Hitler would reward Magda Goebbels by presenting her with his own Nazi Party badge, which he always wore on his tunic.

Magda would remain in the bunker with her husband Joseph until the end. Joseph continued to hold the position of Nazi Gauleiter of Berlin but mostly was eager to remain by Hitler’s side with a front row seat to witness the inferno currently threatening to engulf the city.

With typical gallows humour (Galgenhumor), Berliners were already secretly referring to the city as the Reichssheiterhaufen (the imperial pyre).

Goebbels had in-fact ordered the fire engines of Berlin to leave the city on April 22nd in preparation for the Soviet arrival, so that they should not fall into the hands of the enemy. When head of the Fire Department, Major General Walter Golbach, heard of the order he immediately rescinded it and directed the engines to return to the city. Hearing that he was to be arrested for treachery, Golbach tried to commit suicide and failed.

Bleeding from the face he was taken out by the SS and shot.

For the first time in its history, the Berlin Telegraph Office closed down, on April 22nd 1945. The last message it received was from Tokyo, stating: “GOOD LUCK TO YOU ALL.”

On the same day, the last flight from Tempelhof Airport left, taking with it nine passengers to Stockholm.

Despite the growing shutdown of the city, two operations continued – the meteorological station in Potsdam and eleven of the city’s seventeen breweries, considered essential production, continued making beer.

On the night of April 22nd, Soviet Marshal Konev’s 3rd Guard Tanks Army was ordered to prepare to cross the Teltow canal on the morning of April 24th. Additional infantry and artillery would be assigned to the force, which in the meantime was expected to secure the suburb of Buckow of their right flank and try to make contact with the 1st Belorussian Front – having advanced well into the districts of Lichtenrade, Marienfelde, and Lankwitz by nightfall.

Ivan Konev’s 1st Ukrainian Front had beaten his rival, Zhukov, to the southern suburbs of Berlin – but he needed 24 hours to amass sufficient strength to carry out a coordinated assault on the city centre.

**

Our Related Tours

Want to learn more about the Battle of Berlin? Check out our Battle of Berlin tours to explore what remains of this important urban battlefield.

To learn more about the history of Nazi Germany and life in Hitler’s Third Reich, have a look at our Capital Of Tyranny tours.

Bibliography

Beevor, Antony (2003) Berlin: The Downfall 1945 | ISBN 978-0-14-028696-0

Hamilton, Aaron Stephan (2020) Bloody Streets: The Soviet Assault On Berlin | ISBN-13 : 978-1912866137

Kershaw, Ian (2001) Hitler, 1936–1945: Nemesis | ISBN 0-393-04994-9

Le Tissier, Tony (2010) Race for the Reichstag: the 1945 Battle for Berlin | ISBN: 978-1848842304

Le Tissier, Tony(2019) SS Charlemagne: The 33rd Waffen-Grenadier Division of the SS | ISBN: 978-1526756640

Mayo, Jonathan (2016) Hitler’s Last Day: Minute by Minute | ISBN: 978-1780722337

McCormack, David (2017) The Berlin 1945 Battlefield Guide Part I the Battle of the Oder-Neisse | ISBN: 978-1781556078

McCormack, David (2019) The Berlin 1945 Battlefield Guide Part II The Battle of Berlin | ISBN: 978-1781557396

Moorhouse, Roger (2010) Berlin at War | ISBN: 978-0465028559

Ryan, Cornelius (1966) The Last Battle | ISBN 978-0-671-40640-0

Sandner, Harald (2019) Hitler – Das Itinerar, Band IV (Taschenbuch): Aufenthaltsorte und Reisen von 1889 bis 1945 – Band IV: 1940 bis 1945 | ISBN: 978-3957231581

Shirer, William L. The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich | ISBN 978-1451651683.