On April 23rd, the Berlin Defence Area was still officially without a commandant.

Two days earlier, General Hellmuth Reymann had been relieved of his command for defeatism. Concerned at the lack of attempt to evacuate the civilian population from Berlin, in contrast to the Nazi party officials – many of whom had made sure of their own departure (the so-called Flights of the Golden Pheasants) with special permits issued from Reymann’s headquarters – he was reassigned to command a unit in Potsdam to the south-west of the city.

The man who had been expected to take over from Reymann – Generalleutnant Ernst Kaether – had never actually assumed command.

In one of the strangest episodes to take place during the Battle of Berlin, the man who would actually oversee the defence of the city for the remainder of its time as the capital of Nazi Germany had – on April 23rd – been ordered to report to Adolf Hitler’s Führerbunker to answer to his own charges of defeatism.

And face possible execution.

After moving the headquarters of his LVI Panzer Corps across the river Spree and southern branch of the Teltow Canal, General Helmuth Weidling would receive an order on April 23rd to report to Hitler’s bunker at 6pm. Where he would be received by Generals Krebs and Burgsdorf before being allowed to make his case directly to the Führer.

Weidling was finally in touch with army command after more than 30 hours of silence.

Rumours of the General’s misconduct had spread far and wide – particularly the suspicion that his troops were relocating to Döberitz, near Potsdam. Far west of the city and away from the front.

Weidling would instead explain that he was moving his corps towards Königs Wusterhausen, in accordance with orders issued by the head of the 9th Army – at that time desperately fighting against the Soviet drive east of Berlin. With the misunderstanding corrected, the general was instead informed that, with immediate effect, he should take over the defense of the southeastern and southern defense sectors of Berlin – codenamed A to E – ordering units to disengage the enemy and redeploy to further prepare the city’s defenses.

- The 9th Parachute Division would redeploy to Lichtenburg (Sector A)

- The Müncheberg Panzer Division would redeploy to Karlshorst (Sector B)

- The SS Nordland Panzergrenadier Division would redeploy to Tempelhof (Sector D)

- The 20th Panzergrenadier Division to Zehlendorf (Sector E)

- The 18th Panzergrenadier Division in reserve just north of Tempelhof

- The Corps Artillery to the Tiergarten

General Weidling would move his headquarters to Tempelhof Airport and all but the Müncheberg Division would make it back into the city during the night of April 23rd/24th.

Not only would this mean officially pulling Weidling’s LVI Corps back into Berlin but abandoning any sense of defending the capital on its eastern approaches – and removing the left flank of General Theodor Busse’s 9th Army (still fighting in the field).

Orders for Weidling’s withdrawal would subsequently doom the 9th Army to encirclement.

The General’s decision to move to Tempelhof meant locating his headquarters next to one of the three major ammunition depots in the city. Shortages in equipment and ammunition at this point in the war were common in all field units but the three depots; one in Jungfernheide Volkspark next to the Siemensstadt complex, one in the Grünewald near the War Academy, and the other in Hasenheide Volkspark next to Tempelhof, were stocked to about 80 percent capacity before the fighting in the city.

The armoured vehicles in the area that were still battleworthy were ordered to Tempelhof Airport to refuel from the Luftwaffe aviation stores and prepare for the coming confrontation on the city streets.

Despite the effort to mix units of defenders, with German Army, SS, and Volksstrum forces fighting side by side, the Soviet would eventually bypass the more effective units by destroying the weaker parts of the line and advancing to later pick off the remnants at leisure. As such the three ammunition depots would be quickly overrun when the eventual urban fighting began.

At 4am on April 23rd, an order from Stalin would add further fuel to the competition between the two Soviet Marshals involved in the battle of Berlin. The demarcation line between Georgy Zhukov’s 1st Belorussian Front and Ivan Konev’s 1st Ukrainian Front was now set at Anhalter Bahnhof, the diplomatic station near the Wilhelmstrasse government quarter.

“Lübben, thence to Teupitz, Mittenwalde, Mariendorf, Anhalter Station of Berlin” – Stalin’s order 11074

This left Konev’s troops within ample distance (150 yards west) of the Reichstag building – the main objective in the city – and with his forces thrusting into the south of the city, a real possibility that he might still beat Zhukov to the prize.

As Stalin’s most admired military commander, it seemed only logical that Zhukov would be entrusted with the job of taking Berlin and thus conquering the capital of the fascist enemy. However, whether due to Stalin’s suspicion that Zhukov may be developing enough of a personality cult to threaten his own, or seeking to add some healthy competition to the drive to Berlin, he had tweaked the initial plan for the offensive at the start of April 1945 to allow Konev’s troops to advance close to the 1st Belorussian Front from the south-side of Berlin.

Zhukov far from expected the resistance that occurred on the Seelow Heights and the Oderbruch at the start of the battle, that delayed his forces by three whole days, nor that Konev would punch through so quickly with his tanks and threaten Berlin.

These new orders of April 23rd threatened to change everything.

As the race to see who would be the first to reach the city centre only became more heated.

By April 23rd Soviet troops had arrived into the northern Pankow district of Berlin, leading to the newspaper of the 3rd Shock Army to proclaim: “Motherland rejoice! We are on the streets of Berlin!”

The Second Guards Tank Army would move into Reinickendorf from Wittenau – attempting to push towards the Hohenzollern canal at Jungfernheide.

The 5th Shock Army would start to move down Landsberger Allee in the Lichtenberg district in the early hours of April 23rd, before being engaged by fire from the Friedrichshain Flak tower – destroying a column of heavy tanks.

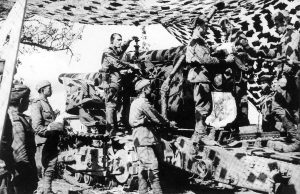

Anti-aircraft guns would play a prominent role in the battle of Berlin – but not always in their intended role. It was on April 23rd that the flak gunners of the German 1st Flak Division would be called upon to repeatedly engage ground targets near the S-bahn train stations that marked the outer ring of the defensive area.

As Soviet troops prepared to move into the city in force they would coordinate their assault with two air control centres, under the command of Air Chief Marshal Novikov. The principal being the headquarters of the 16th Air Army east of Berlin, and the secondary in the north responsible for coordinating ground-attacks.

Beyond the hellish artillery that the Soviet forces would deploy in the Battle of Berlin, they would also utilise air units and individual aircraft to attack specific targets in the city. With observers stationed on rooftops directing aircraft to their targets through the pall of smoke hanging over the city.

Soviet PO-2 biplanes would circle over the city throughout the day, flying in low circles over the battlefield and observing troop movements – and then either marking the locations for air-to-ground fighters to attack or swooping in themselves.

The 7th Department of the Soviet 1st Belorussian Front would also launch a propaganda offensive against the city, air dropping pamphlets telling German soldiers that it was futile to fight on. Almost 50 million of these leaflets would be dropped on the city – and the Department would claim that fifty percent of Berliners who surrendered had one of these leaflets in their possession.

Meanwhile, the head of the German air force had his own personal problems to deal with.

Following Adolf Hitler’s emotional breakdown at his midday briefing on April 22nd, Luftwaffe Chief of Staff, General Koller, had flown south to Bavaria to meet with Hermann Göring and relayed the news of Hitler’s condition and proclamation to his entourage that the war was lost. Adding that the Nazi leader had also stated: “That when it comes to negotiating, the Reichsmarschall (Göring) can do better than I.”

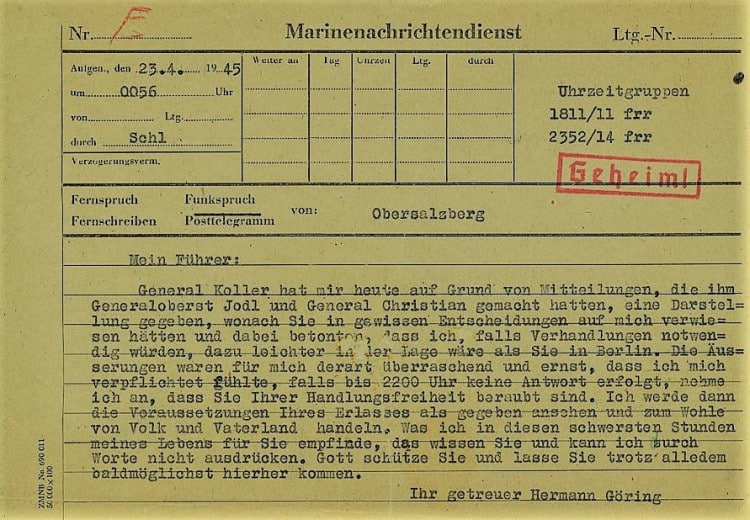

On April 23rd, Göring acted, thinking Hitler incapacitated and that he – being his nominated successor – should take over leadership. In an uncomfortable position, Göring needed to be careful not to overstep his position and be seen as plotting against the Führer but also feared being seen as not fulfilling his duties. He sent a carefully worded message to Berlin:

“My Führer, in view of your decision to remain in the fortress of Berlin do you agree that I take over at once the total leadership of the Reich with full freedom of action at home and abroad as your deputy, in accordance with your decree of June 29 1941? If no reply is received by ten o’clock tonight I shall take it for granted that you have lost your freedom of action, and shall act for the best interests of our country and people. You know what I feel for you in this gravest hour of my life. Words fail me to express myself. May God protect you, and speed you quickly here in spite of it all. Your loyal Hermann Göring.”

Göring’s message was received at the Führerbunker and handled by Martin Bormann, who presented it to Hitler. It didn’t take much for Bormann to convince the Führer that this was outright treason, immediately offering to draft a reply.

Göring would be ordered to resign from all of his post on health grounds.

Furthermore, an SS guard was dispatched to surround the Berghof and Göring effectively became a prisoner of his quarters. With even the kitchens of the property locked, supposedly to prevent the disgraced Reichsmarschall from poisoning himself.

A surprise visitor would also arrive at Hitler’s Führerbunker on April 23rd – Albert Speer had driven from Hamburg, trying to avoid roads blocked with refugees, to see Hitler for the very last time. After taking leave on Hitler’s birthday three days earlier, Speer decided to return and have a private conversation with Hitler.

The conversation would touch on whether Hitler would truly remain in Berlin until the end or travel to Berchtesgaden, in the south. To which Speer advised that it would be better to end it all in Berlin rather than travel elsewhere, where ‘legends would be hard to create”.

By Speer’s account, the two then discussed Hitler’s intention to commit suicide – and Eva Braun’s determination to die by his side.

In the late afternoon, the Nazi leader would take his dog – Blondi – for a walk around the Reich Chancellery gardens before returning back to the Führerbunker for good.

This would be the last time that Adolf Hitler would see daylight.

–

Late on April 23rd, wireless radio communications occurred for the first time between units of Ivan Konev’s 1st Ukrainian Front south-west of Berlin and Georgy Zhukov’s 1st Belorussian Front to the north-west.

Due to the short range of Soviet wireless radio transmissions at the time, this could only mean that the units were close – and soon to complete the encirclement of the Nazi capital.

**

Our Related Tours

Want to learn more about the Battle of Berlin? Check out our Battle of Berlin tours to explore what remains of this important urban battlefield.

To learn more about the history of Nazi Germany and life in Hitler’s Third Reich, have a look at our Capital Of Tyranny tours.

Bibliography

Beevor, Antony (2003) Berlin: The Downfall 1945 | ISBN 978-0-14-028696-0

Hamilton, Aaron Stephan (2020) Bloody Streets: The Soviet Assault On Berlin | ISBN-13 : 978-1912866137

Kershaw, Ian (2001) Hitler, 1936–1945: Nemesis | ISBN 0-393-04994-9

Le Tissier, Tony (2010) Race for the Reichstag: the 1945 Battle for Berlin | ISBN: 978-1848842304

Le Tissier, Tony(2019) SS Charlemagne: The 33rd Waffen-Grenadier Division of the SS | ISBN: 978-1526756640

Mayo, Jonathan (2016) Hitler’s Last Day: Minute by Minute | ISBN: 978-1780722337

McCormack, David (2017) The Berlin 1945 Battlefield Guide Part I the Battle of the Oder-Neisse | ISBN: 978-1781556078

McCormack, David (2019) The Berlin 1945 Battlefield Guide Part II The Battle of Berlin | ISBN: 978-1781557396

Moorhouse, Roger (2010) Berlin at War | ISBN: 978-0465028559

Ryan, Cornelius (1966) The Last Battle | ISBN 978-0-671-40640-0

Sandner, Harald (2019) Hitler – Das Itinerar, Band IV (Taschenbuch): Aufenthaltsorte und Reisen von 1889 bis 1945 – Band IV: 1940 bis 1945 | ISBN: 978-3957231581

Shirer, William L. The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich | ISBN 978-1451651683.