A heavy thunderstorm hit Berlin during the early hours of April 26th bringing with it torrential rain that managed to extinguish some of the fires burning throughout the city.

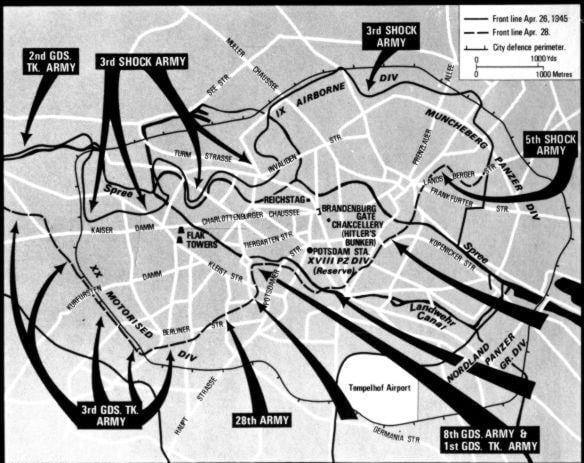

Still, intense fighting continued – especially in the area around Tempelhof airport, with Soviet artillery and Katyusha rocket launchers blasting the aerodrome’s administrative buildings. Wrecked fuselages of Focke-Wulf fighters littered the tarmac, as the remnants of the Müncheberg Panzer Division attempted to hold off the Soviet advance into the south of the city for as long as possible.

The airfield was roughly one mile square and defended by a Luftwaffe unit using anti-aircraft guns in an anti-tank role, base personnel in an infantry role, and a Hitler Youth tank-hunting group serving alongside the remnants of the Müncheberg. The northwest corner of the complex included a massive arc of administrative buildings and hangars where aircraft would remain in stand-by, ready to fly out any remaining Nazi officials.

To the south of the airfield was the S-bahn ring – and the Inner Defense Ring of the Berlin Defense Area with a group of fuelless tanks dug in to hold the perimeter.

A common feature in the city, beyond the guarded barricades made of tram carriages and piled rubble, were tank turrets appearing out of the ground – used as fixed guns in the final battle for the Reich.

On April 25th, the 28th Soviet Rifle Guards Corp along with two of the 1st Guards Tank Army’s brigades fought their way through the two defensive lines at Tempelhof but only managed to get on to the airfield grounds, without securing the buildings.

It would be on April 26th, around noon, that the remaining defenders would be subdued – the airfield commander captured alive – and some 2,000 German women soon put to work to clear the obstacles on the runway. Within thirty six hours of its capture, Tempelhof Airport would be used by the Soviet Air Force, in some instances to fly out seriously wounded casualties to base hospitals.

The troops of Vasily Chuikov’s 8th Guard Army – formed after Chuikov’s victory in the battle of Stalingrad – pushed through the airport and into Schöneberg with the Landwehr Canal firmly on their right flank. Taking Victoria Park, artillery would later be brought into the area and rolled up the Kreuzberg – the highest point in central Berlin – from where the 205mm guns could fire over open sights to the Anhalter Bahnhof less than a mile away.

The point in the city that Stalin had designated the forces of the 1st Ukrainian Front should meet with the 1st Belorussian Front pushing into the north of Berlin.

The situation at the Gatow Airport – in the west of the city – on April 26th was similarly dire, with the airfield falling into Soviet hands the next day. German aviatrix Hanna Reitsch would arrive at the Gatow base on April 26th in one of the last aircraft, bringing with her Luftwaffe Colonel-General Ritter von Greim in a Focke-Wulf 190. Von Greim had been summoned to the Führerbunker to confer upon him the command of the Luftwaffe in the rank of Field Marshal, something that certainly could have been done from a distance. Deciding against travelling through the city on foot, or by vehicle, the two took a Fiesler Storch and flew to an improvised landing strip near the government district.

With the Soviets threatening to take Tempelhof and Gatow for days, the bomb craters on the East-West Axis in the Tiergarten – between the Brandenburg Gate and the Siegessäule – had been filled in to enable planes to land near Hitler’s command post by the afternoon of April 24th.

It would be the only air route out of the city for the final days of the battle.

On April 26th, with the city’s defender’s ammunition dwindling – an attempt was made to drop ammunition containers from Me 109s in the Tiergarten, with only one-fifths of the crates recovered. As a result, two Junkers 52s were flown in and landed at 10:30am on April 26th, bringing with them ammunition and taking off thirty minutes later laden with seriously wounded from Charité hospital. One of these planes would collide with an obstacle on takeoff and crash, killing all on board, so this method was also quickly abandoned.

Six Fieseler Storch aircraft flying to Berlin would also all be shot down, as were 12 Junkers 52 transports bringing in SS reinforcements to the city.

By nightfall, the 3rd Guard Tank Army had overrun the city’s final ammunition dump at the unfinished War Academy in the Grunewald forest (one of three major dumps: Grunewald, Jungfernheide, Hasenheide) advancing around the AVUS speedway and past the Olympic Stadium into Charlottenburg. Slowly fighting their way through residential areas, the tanks of the 3rd Guard would surge forward in columns 100 metres apart, with scouts on the flanks and submachine gunners at the front. Engineers, artillery, and assault groups would follow the tanks with all resistance being smothered by heavy fire while long range artillery pounded the streets ahead.

Adopting new tactics on entering urban terrain was essential to adapt to the new close-combat threats faced on Berlin’s streets – and the disastrously high casualty rate of the initial days of the Red Army’s arrival. Notably due to weapons such as the Panzerfaust – a handheld single fire rocket launcher – employed with deadly success by bands of roaming Hitler Youth to immobilise Soviet armour.

While Soviet tanks – such as the formidable T-34/85 and the huge IS-II – moved through the city streets, alongside SU-76 assault guns and even Sherman tanks; supporting infantry units would now simultaneously advance through the ruins – often blowing holes in buildings to flank defensive barricades and machine gun nests before surprising the defenders from the rear.

The method of sending tanks forward to take ground and ensure the rapidity of the advance may have worked for the Red Army in open countryside but left armour at the mercy of hidden defenders without sufficient infantry support in Berlin’s rubble strewn streets.

Advancing unsupported past strongpoints only left tanks stranded deep in enemy territory – with limited visibility, sporadic radio communications and maps that were often useless considering the amount of destruction caused by the Allied bombers.

The evening of April 25th and throughout the cloudless day of April 26th – the Soviet Red Air Force carried out a massive attack on Berlin – codenamed Operation Salute, organised by Air Chief Marshal Novikov. Following an initial strike of 100 bombers, a total of 1,368 aircraft were thrown at the city throughout the operation’s two days – with 569 dive bombers given specific targets to attack.

Creating an even more hellish moonscape for the Red Army troops to struggle their way through.

Effective – and often creative – use of infantry assault groups would be essential for the Soviet advance.

On April 26th, Red Army soldiers began to use the city’s underground tunnels to infiltrate the city – likely the first use of this subterranean network was by the 7th Rifle Corps, frustrated with its progress through the district of Hohenschönhausen and heading towards Alexanderplatz.

Movement along Frankfurter Allee towards Alexanderplatz by the 5th Shock Army was aided by siege artillery, that could be finally brought into action after the railway bridges at Küstrin on the river Oder were repaired, added to the army reserve artillery now also under control of Marshal Zhukov’s 1st Belorussian Front.

Further north-west, tankers of the 34th Guards Tank Regiment drove over the Potsdamer and Anhalter railway lines and penetrated as far as the Kaiser Wilhelm Gedächtnis Kirche on Kurfürstendamm.

This advance west placed the 1st Belorussian Front well across the line of advance of the 3rd Guards Tank Army and inter-front boundary established by Stalin – into 1st Ukrainian Front territory.

Almost certainly at Marshal Zhukov’s urging, the forces of Vasiliy Chuikov’s 8th Guards Army had placed themselves in a dangerous position – to further deny Ivan Konev’s troops the opportunity to swing around and take the Reichstag first.

A series of German counter attacks carried out on April 26th managed to bring limited success – as the whole area of Friedrichshain to Alexanderplatz was overrun by small groups of German infantry that managed to infiltrate through Red Army lines. IS-II, T 34/85 tanks and self-propelled guns would be brought up by the Soviet troops to try to hold the line – with gunners firing point-blank over open sights.

With the arrival of the Soviet army to the streets of the Nazi capital came increased stories of rapes carried out at gunpoint by Red Army soldiers, families committing suicide en mass rather than deal with the Russian revenge, and Berliners being executed if weapons or uniforms were found in their homes.

In many instances the wounded from the battles would be taken care of in homes rather than medical facilities – with the women and girls left in the city tending to these injured men often immediately removing and burning their uniforms, hoping they would be mistaken for civilians injured in the crossfire if discovered.

Nazi party policy had always been aimed at protecting women from the brutal reality of war – instead propounding the image of the perfect female as being the mother who rears her children to serve the nation. As the male-dominated patriarchal image of Nazi society violently disintegrated, the few remaining radio stations still on air would appeal to women to do their part.

“Take up the weapons of wounded and fallen soldiers and take part in the fight. Defend your freedom, your honour, and your life!”

Few would answer the call.

As the Battle of Berlin continued, the city’s still functioning telephone network took on a new purpose. Despite the expense that had gone into constructing Adolf Hitler’s Führerbunker, the signalling facilities were far from capable of serving as the nerve centre for coordinating a battle of this size. Forced to improvise, the inhabitants of the bunker were left phoning civilian apartments throughout the city, using numbers chosen at random in the telephone book, to ask for a situation report.

If a Russian voice replied, the area could be deemed occupied.

Similarly, Red Army soldiers – the frontiviki tasked with being the first to take Berlin – would make good use of the network – more for amusement than information.

Calling random numbers to announce their arrival.

An extra absurdity added to the carnival of violence taking place across the city.

During the course of the day, Berlin’s telephone links with the outside world would be severed. The network in the city would remain functioning but with radio contact as the only way of the military communicating with forces outside the city.

Regardless of any possible contact; there would be no relief force for the defenders of the Nazi capital.

Responding to Adolf Hitler’s urgent request for assistance in the capital, General Wenck launched his relief attack on the city on April 26th – with his troops covering eleven miles that afternoon and reaching the Beelitz Hospital by evening. Wenck had pushed towards Potsdam, south west of Berlin, where the Soviets did not appear too strong, and the young trainees of the Scharnhorst, Theodor Körner Infantry, Clausewitz Panzer Division, and Ferdinand von Schill infantry had sliced through the Soviet positions.

Beelitz hospital had been in enemy hands for the past three days, with its doctors, medical staff, valuable medical supplies, and around 3,000 wounded more than pleased to see Wenck’s forces. Using a commandeered train Wenck was able to shuttle many of these wounded further west.

As a result of the fighting in the districts around Berlin’s city centre, the remaining armour of SS Nordland Division, 503. Schwere SS-Panzer Abteilung, which included eight Tiger II tanks and several assault guns, were ordered to take positions in the Tiergarten on April 26th, where they would remain for the final fight to take the Reichstag.

That evening, SS leader, Gustav Krukenberg, was informed that the troops of SS Nordland and SS Charlemagne under his command should fall back to Defence Sector Z, right in the heart of Berlin.

At his usual evening conference in the Führerbunker, Hitler was presented with an evacuation plan by Berlin Defence Area Commandant, General Weidling. The breakout would be immediately rejected by the Nazi leader, who would say:

“Your proposal is fine, but what does it imply? I do not want to wander about in the woods waiting to be attacked. I am staying here and will fall at the head of my troops. You carry on your defence!”

Weidling would keep the plan prepared anyway, in case the opportunity should arise to escape the doomed capital.

**

Our Related Tours

Want to learn more about the Battle of Berlin? Check out our Battle of Berlin tours to explore what remains of this important urban battlefield.

To learn more about the history of Nazi Germany and life in Hitler’s Third Reich, have a look at our Capital Of Tyranny tours.

Bibliography

Beevor, Antony (2003) Berlin: The Downfall 1945 | ISBN 978-0-14-028696-0

Hamilton, Aaron Stephan (2020) Bloody Streets: The Soviet Assault On Berlin | ISBN-13 : 978-1912866137

Kershaw, Ian (2001) Hitler, 1936–1945: Nemesis | ISBN 0-393-04994-9

Le Tissier, Tony (2010) Race for the Reichstag: the 1945 Battle for Berlin | ISBN: 978-1848842304

Le Tissier, Tony(2019) SS Charlemagne: The 33rd Waffen-Grenadier Division of the SS | ISBN: 978-1526756640

Mayo, Jonathan (2016) Hitler’s Last Day: Minute by Minute | ISBN: 978-1780722337

McCormack, David (2017) The Berlin 1945 Battlefield Guide Part I the Battle of the Oder-Neisse | ISBN: 978-1781556078

McCormack, David (2019) The Berlin 1945 Battlefield Guide Part II The Battle of Berlin | ISBN: 978-1781557396

Moorhouse, Roger (2010) Berlin at War | ISBN: 978-0465028559

Ryan, Cornelius (1966) The Last Battle | ISBN 978-0-671-40640-0

Sandner, Harald (2019) Hitler – Das Itinerar, Band IV (Taschenbuch): Aufenthaltsorte und Reisen von 1889 bis 1945 – Band IV: 1940 bis 1945 | ISBN: 978-3957231581

Shirer, William L. The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich | ISBN 978-1451651683.