“It is a strange kind of patriotism to wish upon your country its destruction.”

Ruth Andreas-Friedrich, German journalist & anti-Nazi resistance fighter

At the start of the Second World War, US President Roosevelt had implored the European powers to restrict their air attacks to military targets and minimise civilian casualties. A plea Roosevelt no doubt already knew was obsolete before it was even publicised – a gentleman’s agreement issued on the edge of an abyss.

The Luftwaffe and Italian Airforce had already shown its true colours in the skies above Spain – and as the German aerial attacks on Poland would soon confirm: civilian populations were not off-limits – they were more often than not the intended target.

What followed was a terrifying, reciprocal escalation. The Nazi Blitz on British cities was not just answered; it was eclipsed, with RAF Bomber Command perfecting its ‘area bombing’ into a science of industrial-scale destruction. Turning German cities like Hamburg, Berlin, and Dresden into smouldering ruins. This doctrine of incineration, honed in Europe, then eventually exported to the Pacific by the United States to be unleashed on Japan with devastating finality.

Whether these attacks on civilian populations could be said to be criminal can be assessed now in the comfort of retrospection. At a time where, regardless of the conclusion, nothing can change the decisions of the past.

But to ask whether the bombings during the Second World War were legally – or morally – wrong is not to question the history of the conflict; it is to attempt to tell its entire, brutal story.

–

How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb

“We are bombing Germany, city by city, and ever more terribly in order to make it impossible for you to go on with the war. That is our object. We shall pursue it remorselessly. City by city; Lubeck, Rostock, Cologne, Emden, Bremen, Wilhelmshaven, Duisburg, Hamburg – and the list will grow longer and longer. Let the Nazis drag you down to disaster with them if you will. That is for you to decide…We are coming by day and by night. No part of the Reich is safe…for people who work in (factories) and live close to them. There we hit your houses, and you.”

British pamphlet dropped on Germany (1942) – attributed to head of RAF Bomber Command, Arthur Harris

There exists within the modern lexicon of war a subset of terminology deployed with the purpose of dehumanising – and clinically objectifying – the actions committed by belligerents and the environment those actions are conducted in. The kind of phrasing best avoided by any warm hearted writer seeking to expose the realities of war and the human suffering from which it draws its grim momentum.

The most illustrative examples of these, still in popular use, being the phrase: ‘collateral damage’.

As the term first emerged in the 1960 – often credited as having been introduced by Nobel Prize-winning economist and arms control theorist, Thomas Schelling, in his 1961 article ‘Dispersal, Deterrence, and Damage’ – it quickly became entrenched in US military jargon.

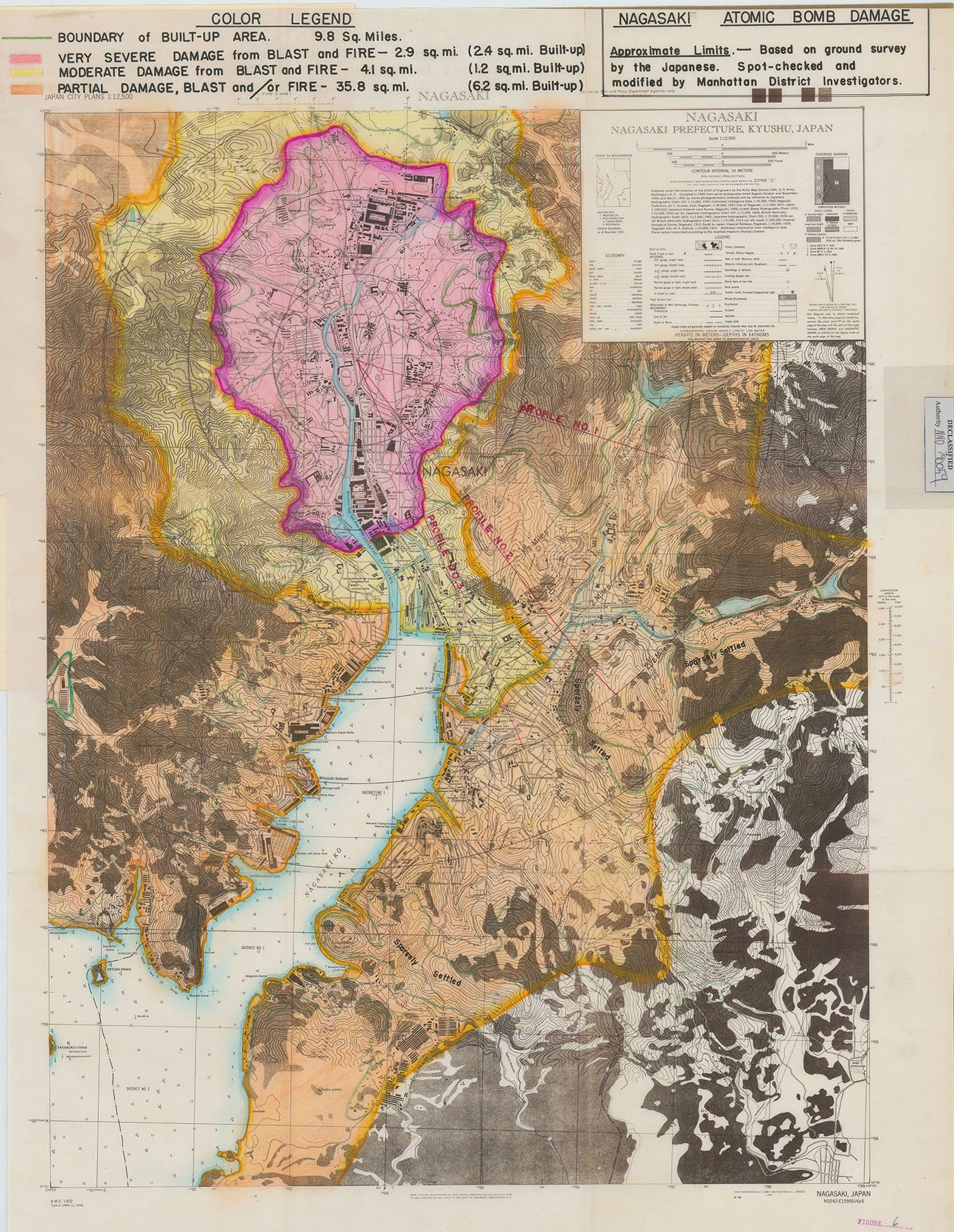

The advent of the nuclear age 15 years early meant the introduction of weaponry capable of inflicting on an enemy damage of a magnitude unseen before in war. The attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945 undoubtedly resulted in plenty of what could be referred to as ‘collateral damage’.

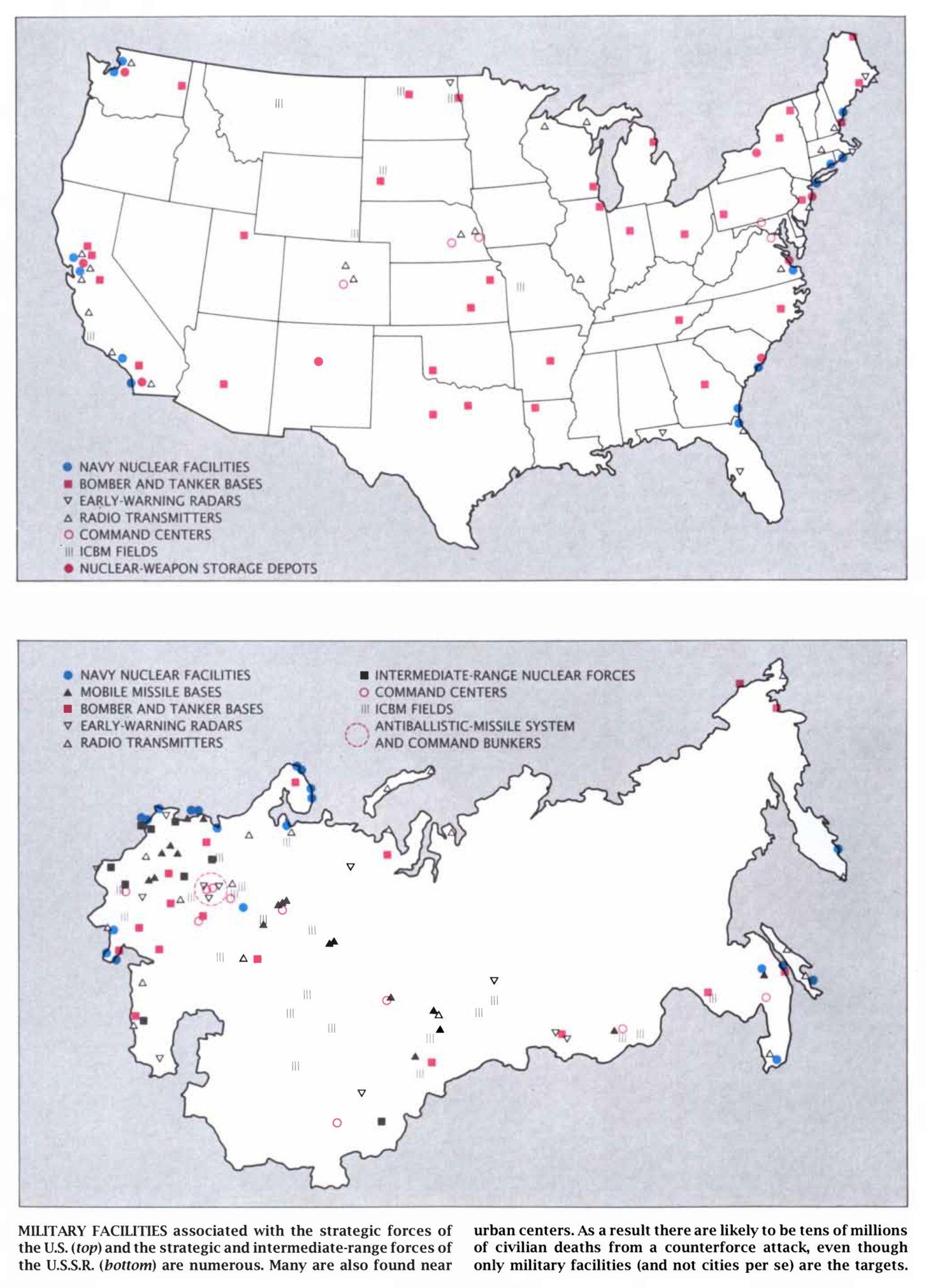

Schelling’s article dealt with the need to disperse US nuclear bombers to improve survivability in the case of a Soviet attack – in-fact discussing the proposal to place said bombers across the country at large city airfields near civilian population.

A move that might deter a Soviet attack when faced with such extent of ‘collateral damage’.

More specifically, Schelling argued that it might be worthwhile to avoid bombing Soviet cities – so that the Soviets in kind respond by not bombing US cities – if only to maintain the threat of being able to bomb them at some point.

Fittingly, conversations between Schelling and film director, Stanley Kubrick, would lead to the 1964 production of ‘Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb’.

From one absurdity to another.

Schelling’s arithmetic was simple: for with the great possibility of destruction came the great responsibility of measuring the effects of such an attack in terms – proportional, moral, and even legal.

Would the Soviets opt for destruction when faced with the likelihood of atrocity?

An even greater question to ask would be whether the use of nuclear weapons, causing such widespread damage and loss of life, can ever be without atrocity?

In purely legal terms, offensives causing collateral damage are not now automatically classed as war crimes.

They are war crimes when the objective is excessively or solely collateral damage.

But so often has the term been used to camoflague horror in the cloak of happenstance.

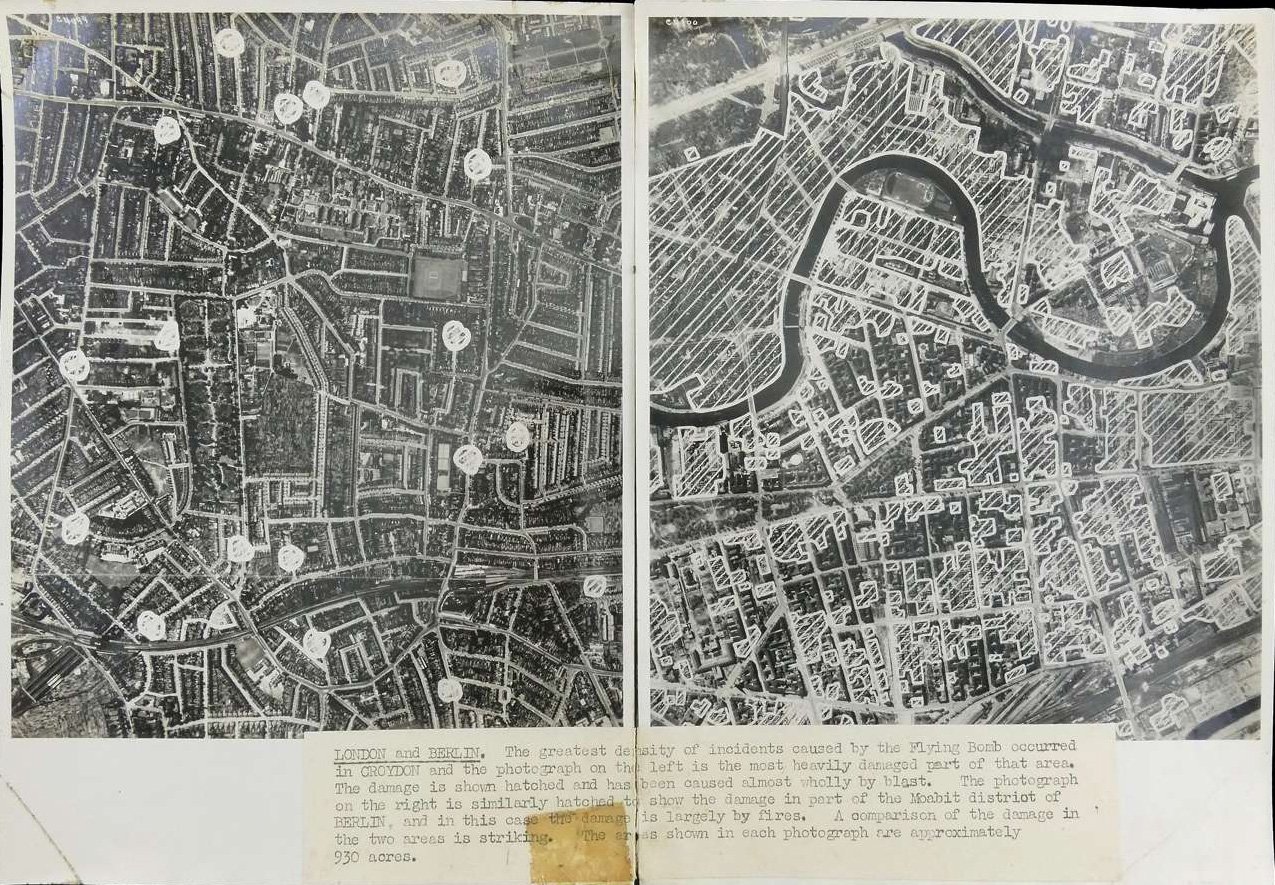

The Second World War equivalent of ‘Collateral Damage’ – in spirit, if not in exact definition – would have been ‘Area Bombing’. Something also referred to as ‘Saturation Bombing’, the more innocuous sounding ‘Carpet Bombing’ – or the distinctly sinister: ‘Obliteration Bombing’.

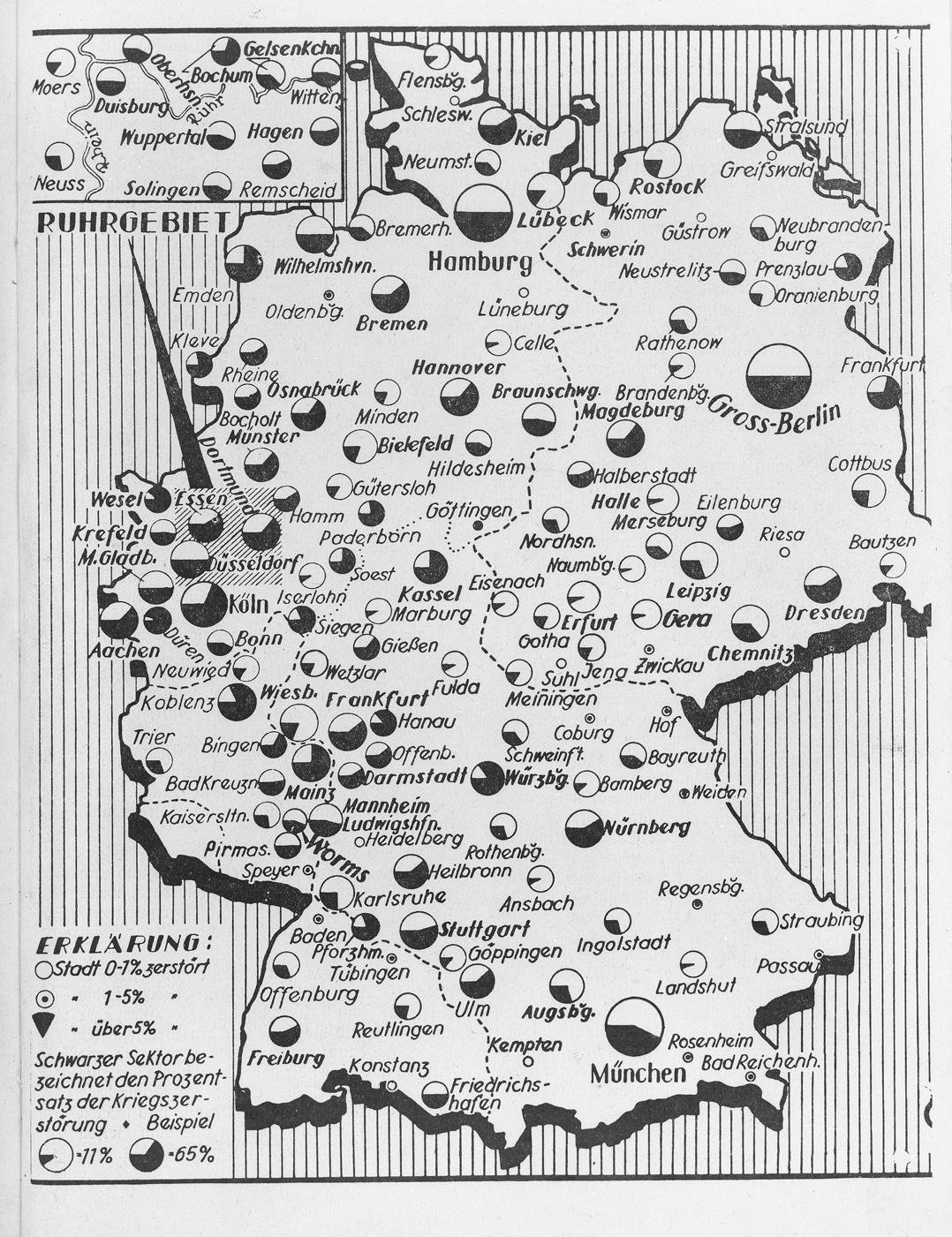

Such as was carried out in Tokyo by the US Airforce in March 1945; in Berlin, Dresden, Hamburg, and many other German cities by the British Royal Air Force between 1943 and 1945; but also by the German Luftwaffe with their indiscriminate attacks on Warsaw, Rotterdam, Coventry, and many other European cities. Add to this list the Soviet bombings of Finland – specifically Helsinki – particularly in February 1944, and the Japanese attacks on Singaporean, Burmese, and Chinese cities.

The antithesis to ‘Precision Bombing’, this type of aerial bombardment was employed by all sides during the Second World War, as a form of strategic bombing – with varying degrees of definable success.

The widespread destruction, civilians casualties, and damage to cultural institutions and landmarks caused by ‘Area Bombing’ – in preference to the targeting of military objects or infrastructure deemed essential to the enemy war effort – has led to the pejorative term ‘Terror Bombing’ also being used to describe such attacks.

In-fact, although the term is considered to have been first printed in a Reader’s Digest article published in the United States in June 1941, it was extensively used by Nazi propagandists, such as Joseph Goebbels, describing Terrorangriffe (‘terror raids’) or Terrorhandlungen (‘terrorist activities’) and Terrorflieger (‘terror flyers’). While carefully avoiding using the same terminology to describe the attacks carried out by the German airforce.

Indeed, the question of whether the British and American air attacks on Germany during the Second World War constitute war crimes remains an issue contested by certain fringe groups particularly within Germany – although also around the world.

The case of the firebombing of Dresden in February 1945 by combined British and American forces has become a cause-celebre among right wing groups. Eager to illustrate the viciousness of the attacks and the needless slaughter of civilians and wanton destruction of a city that up until that point in the war had managed to escape somewhat unscathed.

More remarkable is the way in Germany, the same subject is publicly – and most provocatively – pushed as a necessary and much desired to be repeated matter of honour.

Nowhere else but in Germany is it possible to find open celebration of the area bombing of the country and calls for it to be repeated.

It was Germany that would serve as the proving ground for the effectiveness of these tactics on an official level.

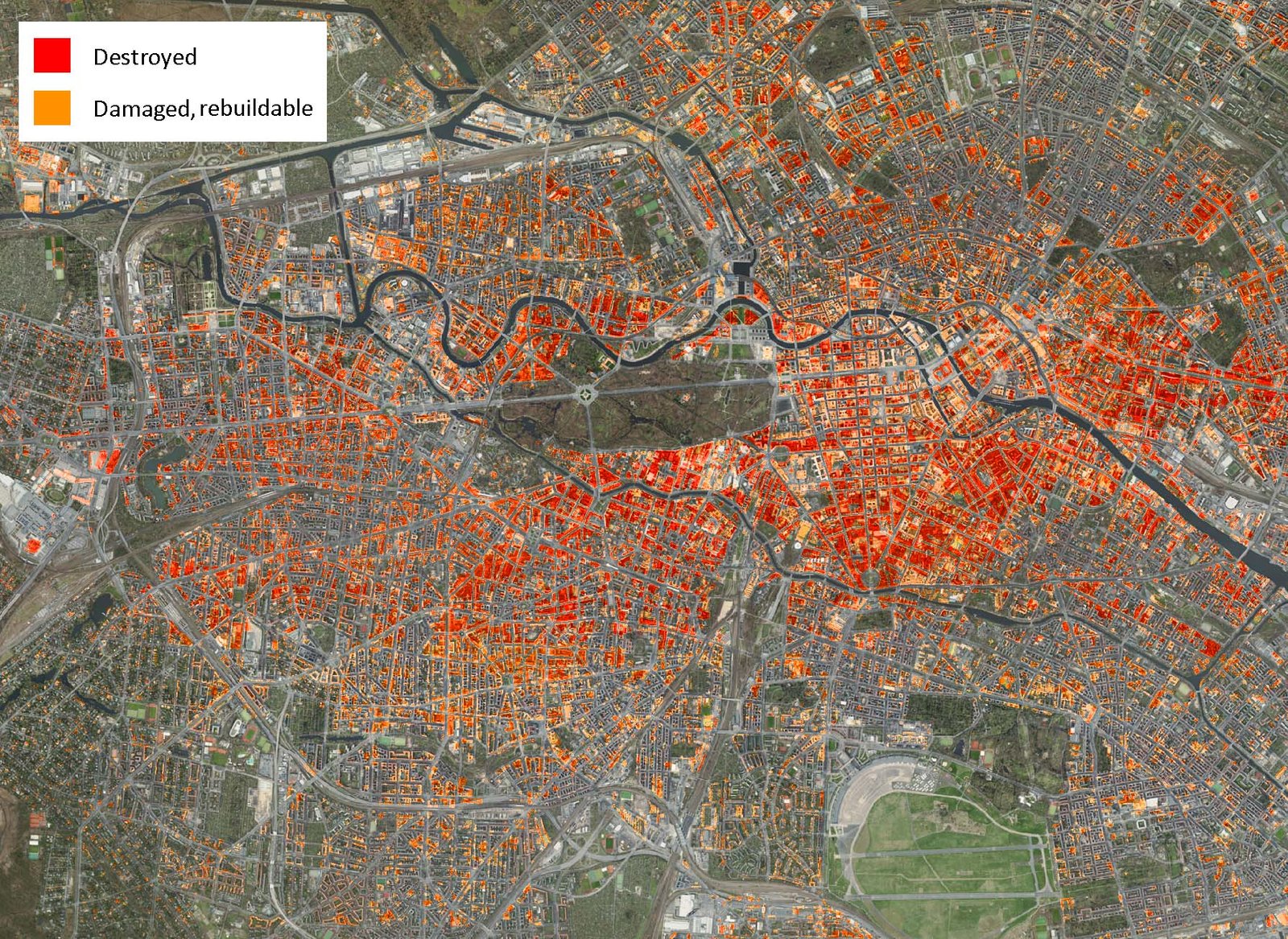

The German capital, Berlin, was targeted more than 350 times during the Second World War by Allied air forces – more than any other city in the world – and subject to incredible destruction, only made worse with the arrival of the Red Army in April 1945 for a ground operation to take the city and, in the process, inflict even more damage.

Retrospectively assessing the actions carried out by the airmen responsible for damage as a result of ‘Area Bombing’ – and the complicity and liability of those who ordered these attacks – requires a more thorough examination of what exactly was carried out.

A journey into intentions and unintended consequences.

–

The Bombing War

“He (the Germans) will recoil eastwards, and we have nothing to stop him. But there is one thing that will bring him down, and that is an absolutely devastating attack by very heavy bombers from this country on the Nazi homeland. We must be able to overwhelm him by this means, without which I do not see a way through.”

Winston Churchill writing to Lord Beaverbrooke, the Minister for Aircraft Production, in 1940

Bombing has always been – and remains – a complicated proposition. Where the bomb hits when dropped is a function of the direction and speed of the airplane at the moment of release. The aerodynamics of the projectile must be taken into account, and the wind and atmospheric conditions while the bomb is in flight.

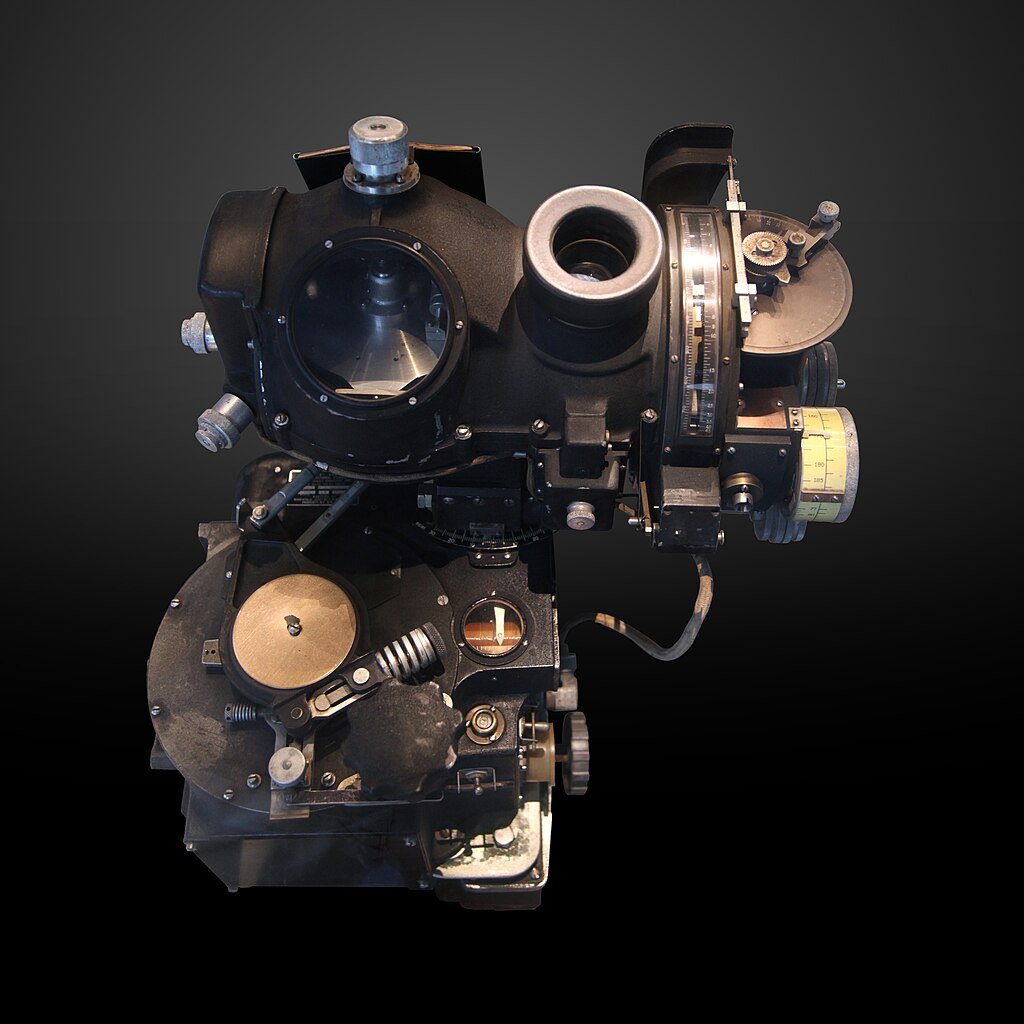

Issues of accuracy in bombing during the Second World War were challenged in later years with the development of bombsights (such as the Norden M series in the United States) and the use of pathfinder planes with flares by the Royal Air Force to illuminate targets for the waves of planes following.

But the measure of explosives necessary to guarantee some success in striking a target also needed to be factored into operations – the bomb yield and blast radius necessary to get the job done.

This issue of ratio of ordnance expended versus results achieved was not limited to aerial operations.

The United States Army would state that it fired 10,000 rounds of small-arms ammunition for each enemy soldier wounded and 50,000 rounds for each enemy killed during the conflict. It took the Germans an average of 16,000 88 mm flak shells to bring down a single Allied heavy bomber.

At the start of the Second World War, the difference in capability and intentions between the Allied and German air armadas was not so great.

In March 1935, Herman Göring officially announced the birth of the Luftwaffe, galvanising the British government – then already wary of the disruption in the ‘balance of power’ in the world, following the Italian invasion of Abyssinia – into boosting the Royal Airforce in size and strength. That 1937 – rather than the earlier speculated 1939 – would be chosen as the year when the Royal Airforce would reach parity with the German Luftwaffe illustrates the importance placed on ensuring readiness for a coming conflict.

As it happens, on September 3rd 1939, only minutes after Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain, had announced Great Britain’s entrance into a war against Nazi Germany, air raid sirens sounded across London. The expected immediate air attack turned out to be a false alarm – the result of a lone French aviator failing to file a correct flight plan – but the foreshadowing was real.

The suspicion was already there that the civilian population in this war, more so than any other before, would also find itself on the front line.

While Roosevelt’s appeal for restraint still echoed, the Luftwaffe was already writing the new rules of aerial warfare.

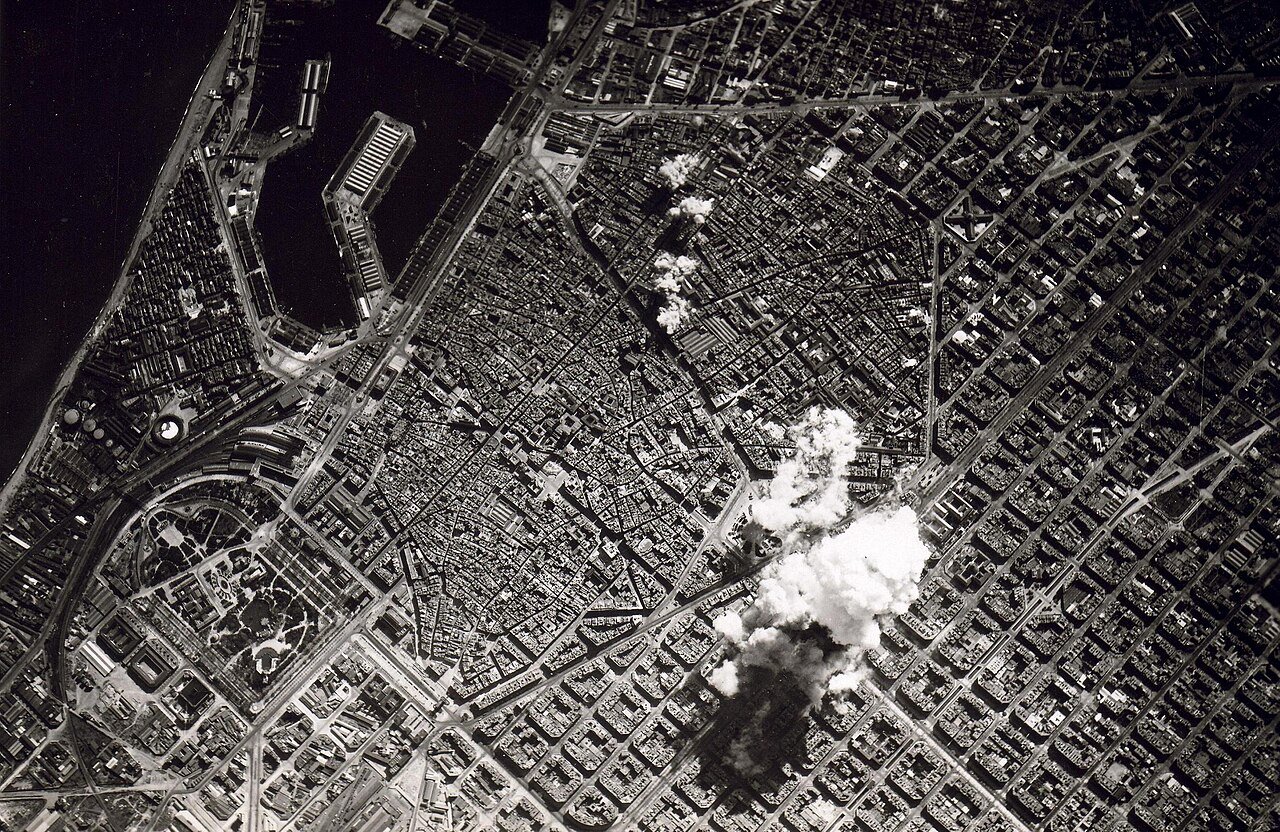

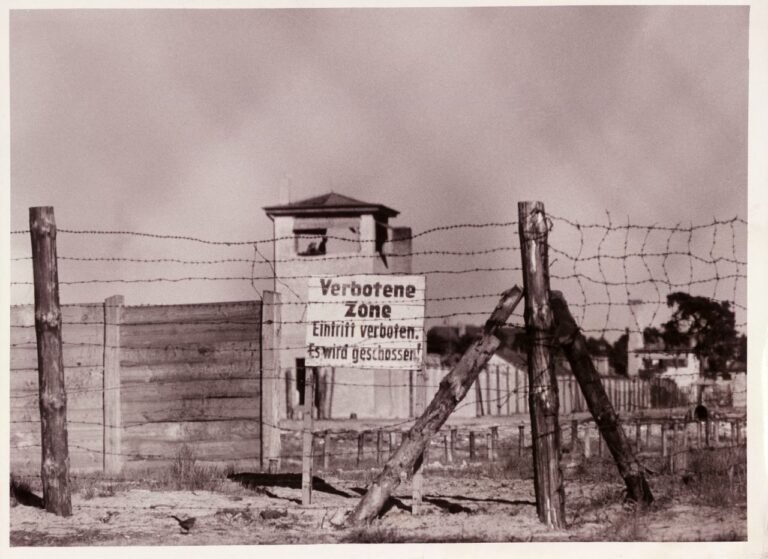

During the invasion of Poland in September 1939, Warsaw was subjected to a relentless bombing campaign that blurred any distinction between military and civilian targets. The Luftwaffe’s ‘Operation Wasserkante’ culminated in a massive raid on September 25th, a day known as ‘Black Monday’, where over 400 bombers dropped a mixture of high-explosive and incendiary bombs across the besieged city, deliberately targeting its infrastructure and terrorising its populace to force a surrender.

For the British War Cabinet, however, the event that truly shattered the apprehension that civilians were sacred occurred much closer to home.

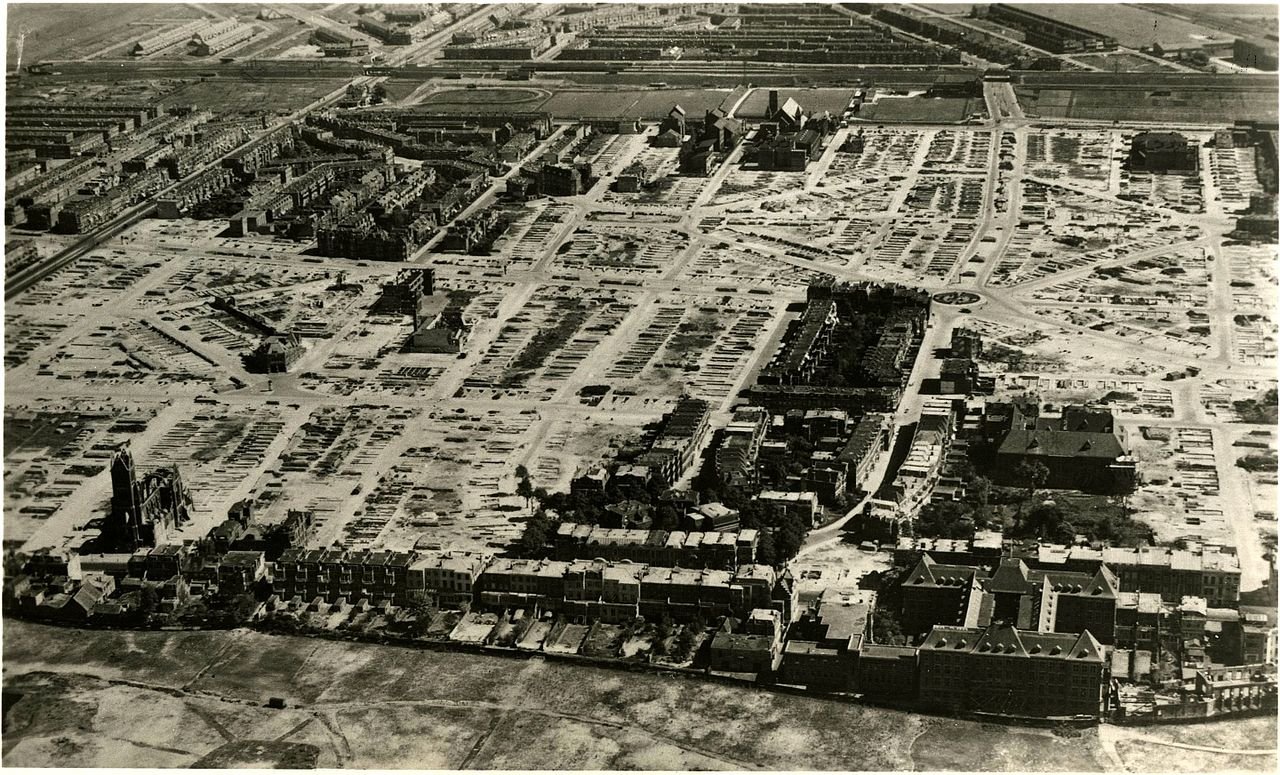

On May 14th 1940, with German forces bogged down by stubborn Dutch resistance in Rotterdam, the German High Command lost its patience. Time was the critical fuel for Blitzkrieg, and the Wehrmacht needed to press on towards France. A force of one hundred Heinkel 111 bombers from Luftflotte 2 was put on standby to break the city’s will.

Though a Dutch surrender was secured at the last minute, the message to abort the raid reached the airbases just as the last bombers were taking off. With the aircraft now over Dutch territory and operating under radio silence, frantic attempts to recall them failed. On the ground, German troops fired red flares—the signal to abort—but through the afternoon haze and the smoke of battle, the pilots of the first wave were too focused on their aiming points in the old city centre to notice.

They unleashed nearly one hundred tons of explosives and incendiaries, killing 900 people and gutting the historic heart of Rotterdam. The second wave saw the flares and aborted, but the damage was done.

To the British, the fact that the bombing may have been a mistake was irrelevant.

The Germans had planned, prepared, and executed a deliberate area-bombing attack on a city centre. The high casualty estimates cemented it as an atrocity in the public mind, a real-world manifestation of the terror long promised by military theorists and previewed at Guernica.

The very next day, on May 15th 1940, Prime Minister Winston Churchill’s War Cabinet authorised bombing raids east of the Rhine. That night, ninety-nine RAF bombers struck industrial targets in the Ruhr.

The directive insisted on positive target identification, but a tacit understanding had been reached: the gloves were coming off.

The spiral of escalation tightened on the night of August 24th 1940, when a handful of Luftwaffe bombers, off-course from their intended industrial targets, accidentally dropped their bombs on London.

In Berlin, Luftwaffe Chief, Hermann Göring, was furious – reportedly ordering the responsible crews be transferred to the infantry. In London, however, there was no knowledge of the error. Seeing only a deliberate attack on the capital, the War Cabinet ordered an immediate retaliatory raid to boost British morale. The following night, a hastily assembled force of eighty-one bombers was dispatched to Berlin. The raid was a tactical failure, with only a third of the crews claiming to have found the city through difficult weather, doing negligible physical damage.

Psychologically, however, it was a thunderclap.

Göring had boasted that an enemy bomb would never fall on Berlin; its citizens were shocked, and their morale briefly plummeted.

This exchange triggered Hitler’s fateful decision to shift the Luftwaffe’s focus from destroying RAF Fighter Command’s airfields to terrorising London, a move that gave the RAF the breathing room it needed to win the Battle of Britain.

But the Blitz, which began in earnest on September 7th 1940, would sear itself into the British psyche and profoundly shape the future of its own bomber offensive. For eight months, the Luftwaffe pounded British cities.

The attack on Coventry on November 14th 1940, was a grim landmark.

In a relentless ten-hour raid, the Luftwaffe massively applied air power against a small city with the clear objective of its obliteration. The destruction of its cathedral, factories, and thousands of homes hardened British resolve and created an overwhelming public appetite for retribution. The thoughts forming in the Air Staff were heavily influenced by these nightly scenes of destruction.

British retribution would be swift – and applied to targets across Germany.

As Air Marshal Arthur Harris would later recall, standing on the Air Ministry roof with Chief of the Air Staff Sir Charles Portal during one raid, watching London burn, he remarked grimly, “Well, they are sowing the wind.”

Portal’s promotion to Chief of the Air Staff in October 1940 was another pivotal moment.

More than anyone, he began to steer RAF Bomber Command away from the fiction of purely precision strikes towards a deliberate strategy of targeting the German population itself.

A directive issued to his successor, Sir Richard Peirse, hinted at this, calling for attacks on major urban areas to cause “the greatest possible disturbance…to the civil population.”

This shift was codified on July 9th 1941, when a further directive made the strategy explicit: Bomber Command’s primary targets were now Germany’s transportation system and “the morale of the civil population as a whole and of the industrial workers in particular.”

With these fateful words, the ‘area bombing campaign’ became official policy.

The Air Staff, eager to experiment with the de-housing potential of incendiary bombs, selected the medieval Hanseatic city of Lübeck on the Baltic coast. Its tightly packed, timber-framed buildings made it a perfect laboratory. Though officially justified as a strike on a key port for Swedish iron ore and a U-boat training station, the true target was the flammable cityscape.

On the night of March 28th 1942, 234 bombers attacked, with devastating success. Arthur Harris, who had recently taken command, wrote triumphantly, “On the night of 28–9 March, the first German city went up in flames.”

A month later, the ancient city of Rostock suffered the same fate, with 70% destroyed in three raids. The outrage in the German high command was immediate, inspiring a series of retaliatory attacks on historically and culturally significant British cities, which became known as the “Baedeker Raids,” after the German spokesman threatened to bomb every building marked with three stars in the Baedeker Tourist Guide.

These successes whetted Harris’s appetite.

He was convinced that the bomber was a war-winning weapon, capable of pounding an enemy population into submission without the need for a costly land invasion. To prove it, and to erase the lingering impression of Bomber Command’s earlier ineffectiveness, he conceived of a spectacular display of force: a 1,000-bomber raid.

The plan, codenamed ‘Operation Millennium’, was designed to overwhelm a city’s defences—its anti-aircraft batteries, its firefighters, its medical services—through sheer concentration of force within a 90-minute window.

On the night of May 30th 1942, Harris staked the entirety of his front-line and reserve forces on this gamble.

Nearly 900 bombers reached the target of Cologne, dropping over 1,700 tons of explosives and incendiaries. The city suffered more damage in that single night than in all previous raids combined. The attack was an unqualified propaganda victory, boosting morale at home and cementing Harris’s position. It was, as he later wrote, “an irrefutable demonstration of the power of what was to all intents and purposes a new and untried weapon.”

Subsequent 1,000-bomber raids against Essen and Bremen were less successful, but the point had been made.

By late 1942, a convergence of technology, production, and political will was transforming RAF Bomber Command into a truly formidable weapon of mass destruction.

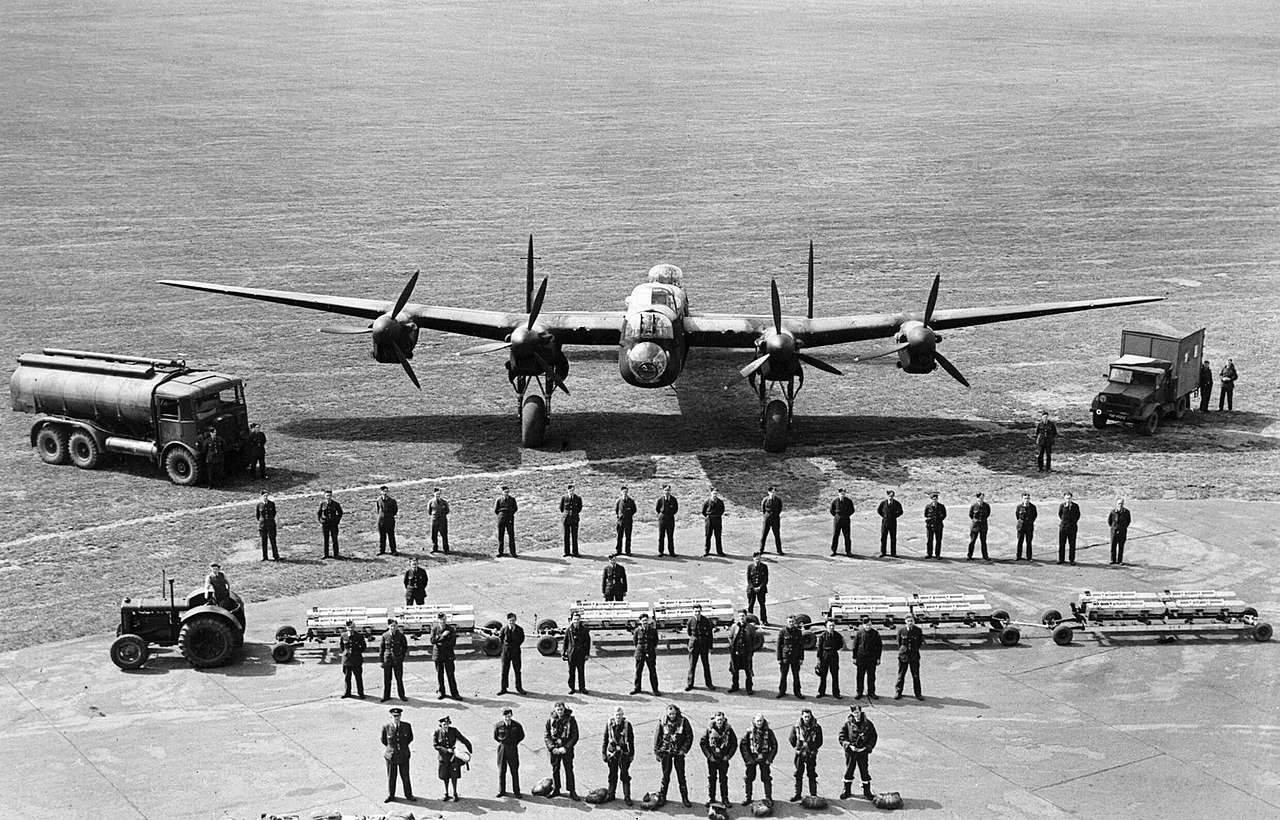

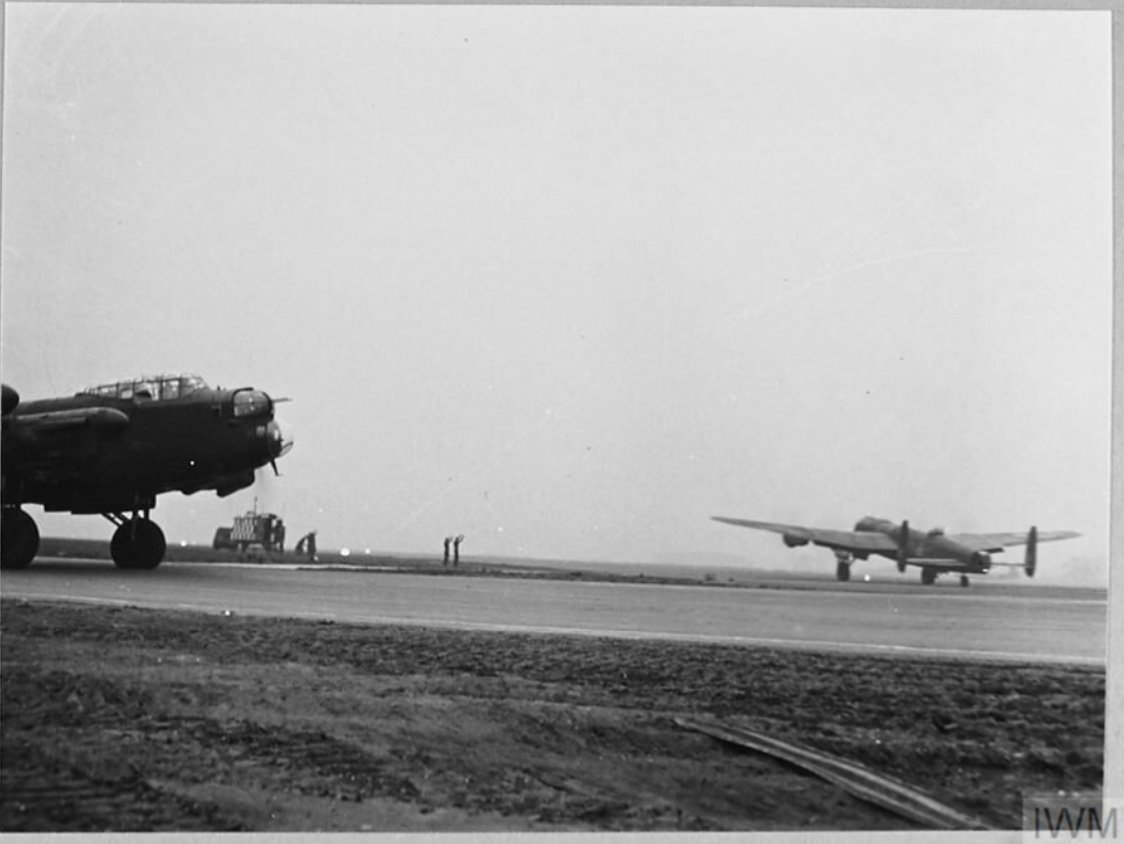

The arrival of new four-engine heavy bombers, chiefly the Avro Lancaster, more than doubled the bomb load per aircraft. To solve the persistent problems of navigation and target identification, new technologies were being deployed. The elite Pathfinder Force was created to lead the bomber stream and mark targets with flares. Navigational aids like OBOE and H2S radar allowed crews to find their targets with far greater accuracy, even through cloud cover.

The crude, scattered raids of 1940 were giving way to a systematised, technologically-driven process of urban annihilation.

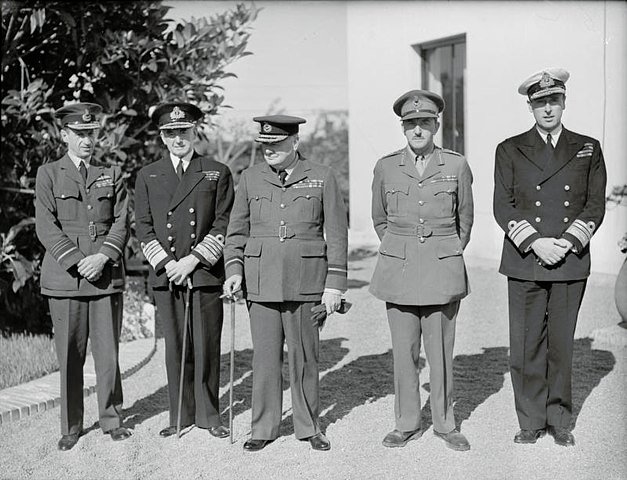

This new capability was given a clear and brutal mandate at the Casablanca Conference in January 1943.

There, Churchill and Roosevelt laid out the Combined Bomber Offensive, a strategy of round-the-clock bombing. The American Eighth Army Air Force, with its heavily defended B-17 Flying Fortresses and advanced Norden bombsight, would conduct precision daylight raids against German industry. At night, RAF Bomber Command would continue its work of “the progressive destruction and dislocation of the German military, industrial and economic system, and the undermining of the morale of the German people to a point where their capacity for armed resistance is fatally weakened.”

The firestorm raids on Hamburg in July 1943, codenamed ‘Operation Gomorrah’, were the horrific culmination of this evolution.

Utilising a new countermeasure called ‘Window’—strips of aluminum foil that blinded German radar—the RAF attacked the city with devastating effect. On the second major raid, a concentration of incendiary bombs overwhelmed the city’s fire services and created a terrifying new phenomenon: a firestorm. The conflagration reached heights of 7,000 feet, generating winds of over a hundred miles an hour that sucked the air out of shelters and melted the asphalt in the streets. It was the first time bombing had ever created such an effect, and it marked the perfection of a horrifying new form of warfare.

By the autumn of 1943, Arthur Harris was finally in possession of the force he had long envisioned.

He had the men, a growing armada of heavy bombers, and the methods, refined in the flames of Lübeck, Cologne, and Hamburg. He also had the political backing for a campaign of attrition aimed squarely at Germany’s cities and their inhabitants.

The initial reluctance of 1939 had been burned away in a three-year crucible of retaliatory escalation and technological advancement.

With the industrial Ruhr now heavily battered and the American air fleets gathering strength for the final push, the gaze of Bomber Command turned inexorably toward the ultimate prize: the political, administrative, and symbolic heart of the Third Reich itself.

–

The Battle For Berlin

“We have the one directly offensive weapon in the whole of our armoury, the one means by which we can undermine the morale of a large part of the enemy people, shake their faith in the Nazi regime, and at the same time and with the very same bombs, dislocate the major part of their heavy industry and a good part of their oil production.”

Air Chief Marshal, Sir Charles Portal, Chief of the British RAF Air Staff (1940)

Heartened by the terrifying success of the firestorm raids on Hamburg, Air Marshal Arthur Harris was more convinced than ever of his central, unwavering belief: that a strategic bombing offensive, if given absolute priority and waged without restraint, could win the war on its own.

It would, he insisted, break the will of the German people and shatter the Nazi regime, thus precluding the need for a bloody and protracted land invasion of Europe.

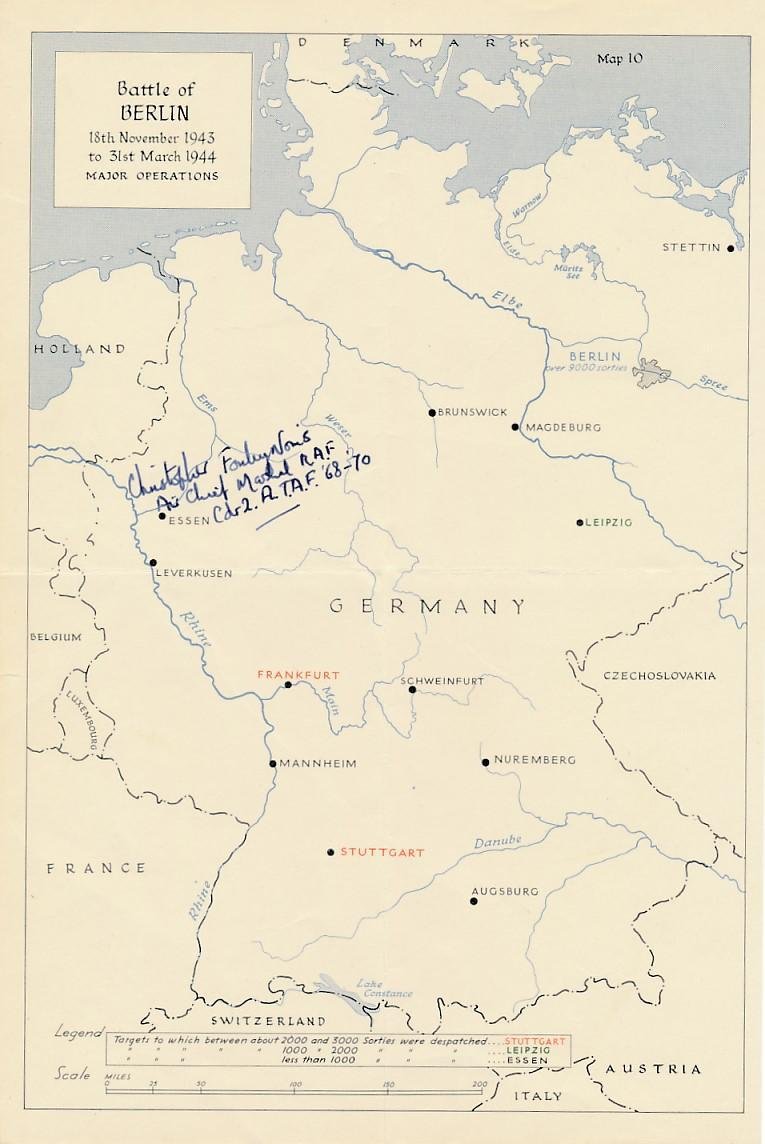

By the autumn of 1943, with a nightly average of 800 heavy bombers at his disposal and new navigational technologies operating with deadly efficiency, Harris decided the time had come to put his theory to its ultimate test.

The target would be the nerve centre of the Reich: Berlin.

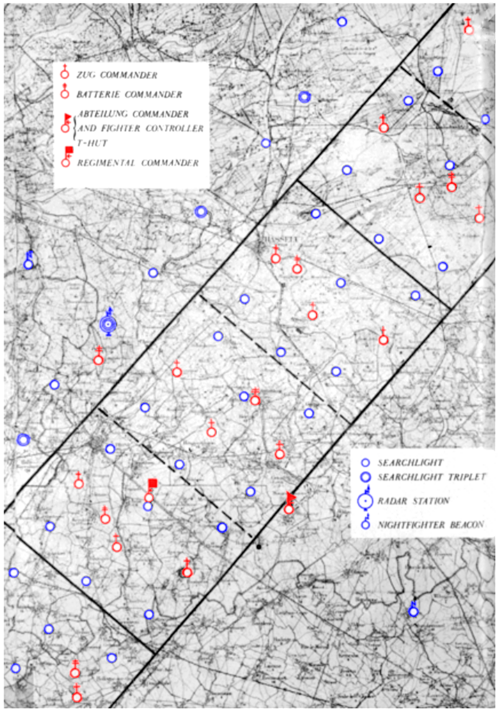

An assault on “Big City,” as the crews called it, was a uniquely daunting proposition. Lying nearly twice as far from English airbases as the Ruhr, Berlin was a distant and sprawling metropolis, difficult to navigate to and even harder to damage comprehensively. The long flight path gave the formidable German night-fighter force ample time to intercept and harry the bomber stream. But with the longer nights of winter approaching, Harris prepared his offensive.

In an optimistic memorandum to Winston Churchill, he made an audacious promise: “We can wreck Berlin from end to end… It will cost us between 400–500 aircraft. It will cost Germany the war.”

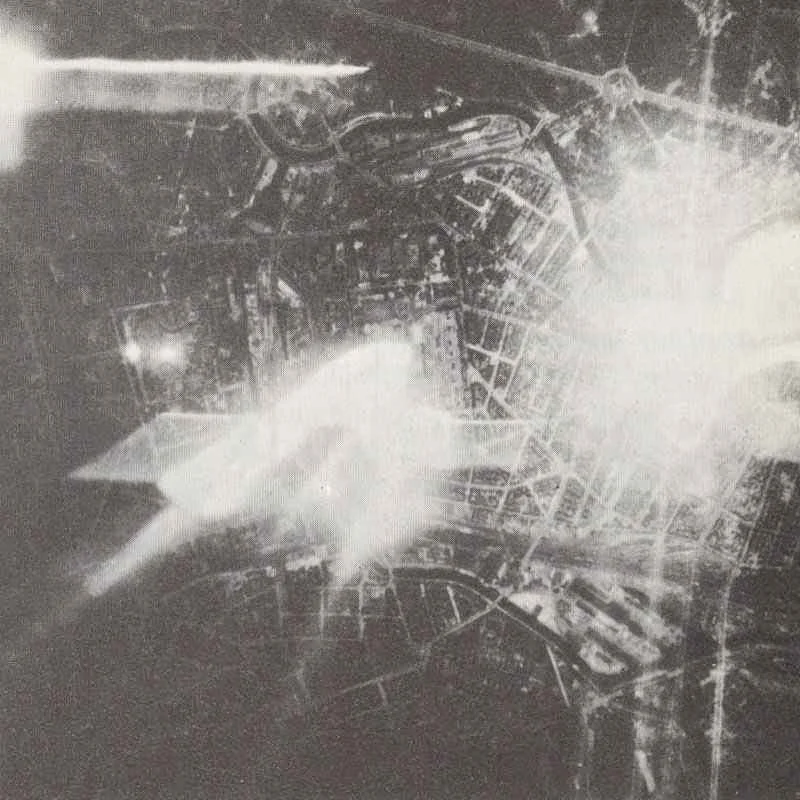

On the night of November 18th 1943, he launched the first major raid of what he officially designated the ‘Battle of Berlin’.

The campaign began with shocking ferocity.

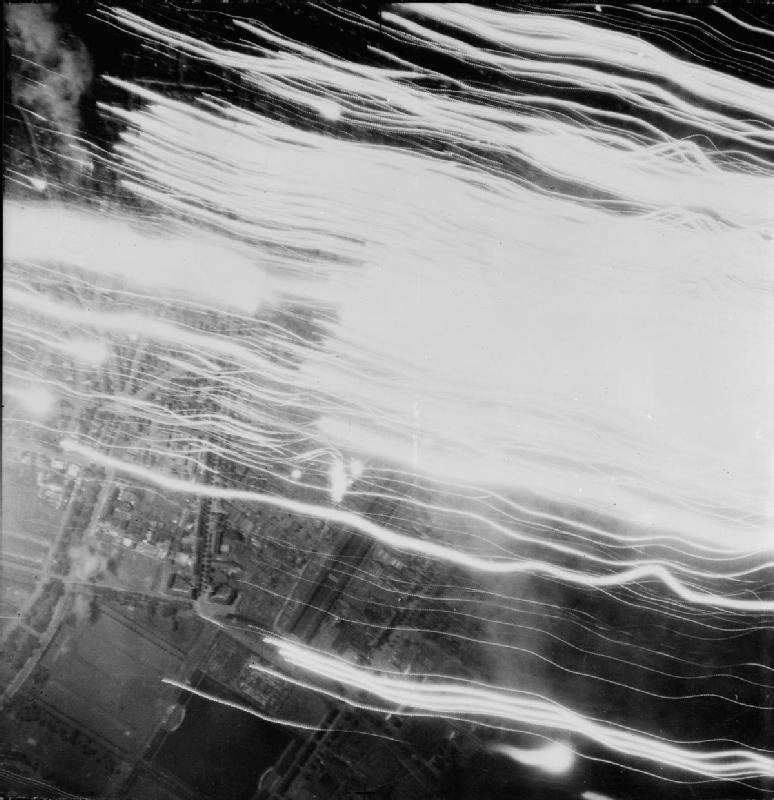

On the nights of November 22nd and 23rd alone, over 1,500 sorties were flown against the capital. The destruction in the central and western districts was immense, killing or injuring 9,000 Berliners and rendering 175,000 homeless. The skies over the city erupted in a man-made aurora of searchlights, flak bursts, and the eerie glow of target markers.

Waves of Lancasters and Halifaxes rained down a torrent of high-explosive ‘blockbusters’ and hundreds of thousands of incendiary bombs.

The initial raids gutted symbols of both the old Germany and the new – and final – Reich; the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church was left a blackened, hollowed-out shell, and flames consumed parts of the Reichstag building, Charlottenburg Palace, and the State Opera House.

Entire city blocks were erased, creating canyons of fire where avenues once stood. Below ground, the U-Bahn stations, serving as public shelters, became scenes of unimaginable horror as smoke and toxic fumes seeped into the crowded tunnels.

Despite this promising start, the battle soon devolved into a brutal war of attrition. Harris had written to Churchill that he could wreck Berlin – but only if the USAAF would come in on it.

The American Eighth Air Force, however, remained largely committed to its daylight precision strategy, leaving Bomber Command to fight the battle alone in the dark.

The German defences adapted with lethal skill. Night-fighter controllers marshalled their twin-engine Messerschmitts and Junkers into the bomber stream, where pilots engaged in deadly cat-and-mouse games amidst the flak.

Furthermore, consistently terrible weather conditions over Northern Europe plagued the offensive.

Bomber streams became diffused, with a rising percentage of bombs scattering harmlessly across the Brandenburg countryside. The strain on the aircrews was immense, flying six- to eight-hour missions in freezing, unpressurised cabins, stalked by unseen enemies in the dark, and hoping to survive long enough to complete their thirty-mission tour of duty.

A grim disaster on the night of December 16th underscored the operational hazards; after a difficult raid, the returning bombers found their home bases in England shrouded in impenetrable fog. Twenty-nine Lancasters, many with battle damage or running low on fuel, crashed while attempting to land, killing 140 airmen who had already survived the trip to hell and back.

Harris pressed on relentlessly, continuing the heavy attacks on Berlin and other German cities through to March 1944.

But the promised collapse of German morale never materialised.

The city, though grievously wounded, refused to die.

Its defences remained potent, and the cost to Bomber Command became catastrophic.

Diligent Berlin city officials would eventually compile a list of the damage inflicted on the city over these five nights in November 1943:

- 8,701 buildings containing 104,613 individual apartments were completely destroyed.

- 4,330 people were killed, although not including 105 people crushed to death after panicking in an air raid shelter in Neukölln.

- Over 400,000 people would be bombed out of their homes with the district of Tiergarten – that had the misfortune of being in the path of the bombers every time they approached from the west – most affected.

By the end of the campaign, over 1,000 bombers—more than double Harris’s initial estimate—had been lost over Germany or crashed on return. Nearly 6,000 highly-trained airmen had been killed, wounded, or captured.

The consensus among most post-war analysts, and the official verdict of the RAF’s own historians, was damning.

As one commentator summarised, “The Luftwaffe hurt Bomber Command more than Bomber Command hurt Berlin.” The Official History was even more blunt in its judgment: “The Battle of Berlin was more than a failure, it was a defeat.”

The failure of the Berlin campaign forced a strategic re-evaluation. A new directive, issued to Harris on September 25th 1944, explicitly ordered him to prioritise oil installations and communications to support the advancing Allied armies.

The “general industrial capacity” of cities became a secondary objective, to be attacked only when weather or other conditions prevented strikes on the primary targets.

But Harris, a man of unshakeable conviction, interpreted this as a carte blanche. In his view, Churchill’s encouragement to continue striking German industry meant he had license to also resume his area bombing campaign with impunity.

As he famously argued, “bombing anything in Germany was better than bombing nothing.”

By this point, the force at his command was no longer the one that had been bloodied over Berlin. It was a mighty armada of 1,400 heavy bombers, mostly state-of-the-art Lancasters and Halifaxes, supported by swift Mosquito pathfinders.

The Luftwaffe, decimated by the American escort fighters, was a shadow of its former self. German cities were now all but defenceless.

On raids where losses had once been a terrifying 5 to 10 percent, the attrition rate now plummeted to a statistically negligible 0.4 percent.

Despite the directive, Harris ensured that only 6 percent of his command’s bomb tonnage in the war’s final months fell on oil targets.

He was determined to complete his ‘city programme’.

He had a list, he told his superiors, of fifteen major German cities not yet properly attacked, and he remained utterly convinced that their systematic destruction would be a greater factor in ending the war than anything the Allied ground forces could achieve.

Among the fifteen unscathed major cities on his destruction list was a cultural jewel on the River Elbe, a city that had so far escaped the inferno: Dresden.

–

The US Army Airforce In Europe

“We do not regard a 15-foot square … as being a very difficult target to hit from an altitude of 30,000 feet,”

Theodore H. Barth, president of Carl L. Norden Inc., producer of the Norden bombsight (1940)

While RAF Bomber Command was developing its doctrine of nocturnal area bombing, a different theory of air power was being forged across the Atlantic.

The American approach, conceived in the 1930s at the Air Corps Tactical School in Alabama, was a doctrine born of a uniquely American confidence in technology and moral purpose. It rejected the notion of indiscriminate bombing as both inefficient and unethical. The strategy championed by the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) was one of high-altitude, daylight precision bombing aimed exclusively at targets of military significance.

As its chief, General Henry H. “Hap” Arnold, declared in 1940, “The Air Corps is committed to a strategy of high-altitude precision bombing of military objectives.”

The theory was elegant: by surgically destroying key nodes of the German war machine—ball-bearing plants, aircraft factories, synthetic oil refineries—the Allies could cripple the Third Reich’s ability to fight, all while minimising civilian casualties.

The linchpin of this strategy was the combination of the formidable Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress bomber and the technologically advanced Norden bombsight.

The B-17, bristling with defensive machine guns, was designed to fly in tight, self-defending formations deep into enemy territory. The Norden was a gyroscopic mechanical computer of astonishing complexity, theoretically capable of allowing a skilled bombardier to place a bomb inside a 100-foot circle from 20,000 feet.

When the Eighth Army Air Force, the “Mighty Eighth,” began arriving in England in 1942, its leadership brought with them a firm conviction that this combination of aircraft and technology would allow them to wage a more effective and more humane air war than their British counterparts.

This theory, however, soon collided with the brutal reality of the European air war.

The skies over Germany were not the clear, calm testing grounds of the American desert. They were choked with industrial haze, obscured by relentless cloud cover, and, most critically, fiercely defended.

The German Luftwaffe’s fighter arm and the thick belts of anti-aircraft artillery, or flak, made every mission a harrowing ordeal.

The Norden bombsight required a long, straight, and stable bombing run to function correctly—a suicidal manoeuvre when faced with a sky full of exploding shells and swarms of enemy fighters. This meant that even the most meticulously planned raid was subject to profound error.

The inherent inaccuracy of the endeavor, multiplied over hundreds of missions, demonstrates a grim application of the principle of error accumulation.

The pre-war claim of dropping a bomb in a pickle barrel was a fantasy; a more realistic wartime analysis revealed a mere 1.2 percent probability of a single heavy bomber hitting a 100-foot-square target from altitude. Even under combat conditions, post-war studies found that the Eighth Air Force placed only 31.8% of its bombs within 1,000 feet of its designated aimpoint.

Each individual bombing run, therefore, carried with it a high statistical probability of missing its mark. When this action was repeated thousands of times by fleets of hundreds of bombers, the law of large numbers guaranteed a catastrophic accumulation of “errors.” Bombs intended for a Focke-Wulf factory or a railway marshalling yard would instead rain down on the surrounding residential blocks, schools, and hospitals. This was not necessarily a failure of intent, but a predictable consequence of applying an imperfect technology on an industrial scale.

The grim reality of ‘collateral damage’ – before the term even entered the lexicon – became an accepted, unavoidable cost of the daylight bombing campaign.

Ultimately, the relentless application of an imprecise action, no matter the precision of the intent, inevitably led to devastating civilian casualties.

For much of 1942 and 1943, the USAAF paid a staggering price in blood for these marginal results.

Flying unescorted deep into Germany, the B-17 formations were savaged by the Luftwaffe. The nadir came during ‘Black Week’ in October 1943, when a series of raids against targets like the Schweinfurt ball-bearing plants resulted in the loss of 148 bombers and nearly 1,500 airmen in just a few days—an unsustainable rate of attrition.

It became terrifyingly clear that daylight precision bombing could not succeed without first achieving air superiority.

This reality prompted a crucial strategic shift: the primary target became the Luftwaffe itself.

The introduction of long-range escort fighters, most iconically the P-51 Mustang, changed the course of the air war. These fighters could accompany the bombers all the way to their targets and back, engaging and systematically destroying the German fighter force.

By the spring of 1944, after a series of massive aerial battles, the Luftwaffe was a broken force, granting the Allies command of the skies over Germany and finally allowing the American precision bombing doctrine a chance to prove its worth.

With air superiority achieved, the bombers could attack their targets with greater deliberation and accuracy, playing a vital role in crippling German oil production and transportation networks in the run-up to and following the D-Day landings.

Yet even then, the fundamental limitations of technology and the environment ensured that the ideal of surgical strikes remained elusive, and German cities continued to suffer widespread destruction.

For most of the war in Europe, the United States Army Air Forces held, at least in principle, to its doctrine of precision bombing. Its reputation was built on daylight attacks against military and industrial targets, a clear philosophical line drawn between its methods and the nighttime area-bombing of the RAF.

Overall, less than four percent of US bombs in Europe were aimed at civilians.

The main targets for the AAF were marshaling yards (27.4 percent of the bomb tonnage dropped), airfields (11.6 percent), oil installations (9.5 percent), and military installations (8.8 percent).

That reputation, however, would be forever tarnished by American involvement in one of the war’s most ferocious and controversial attacks on a civilian population: the bombing of Dresden in February 1945.

Before Dresden, however, Berlin would suffer the wrath of the ‘Mighty Eighth’.

By early 1945, the strategic context of the war had shifted dramatically.

The Red Army was advancing relentlessly from the East, and Allied high command was seeking ways to aid its Soviet allies by disrupting the German war effort on the Eastern Front.

At the request of the British Prime Minister, Air Chief Marshal Portal proposed a series of massive attacks on the major transport hubs of Berlin, Leipzig, Chemnitz, and Dresden to sow chaos, hamper the movement of German reinforcements, and obstruct the evacuation of refugees fleeing the Soviet advance.

The campaign began on February 3rd 1945, when the Eighth Air Force mounted one of its largest raids of the war, sending 1,000 bombers against Berlin.

Targeting the city’s railway and administrative centers, the attack caused enormous devastation, with German authorities reporting 25,000 deaths.

After a ten-day pause due to bad weather, the Allied air fleets turned their attention to Dresden.

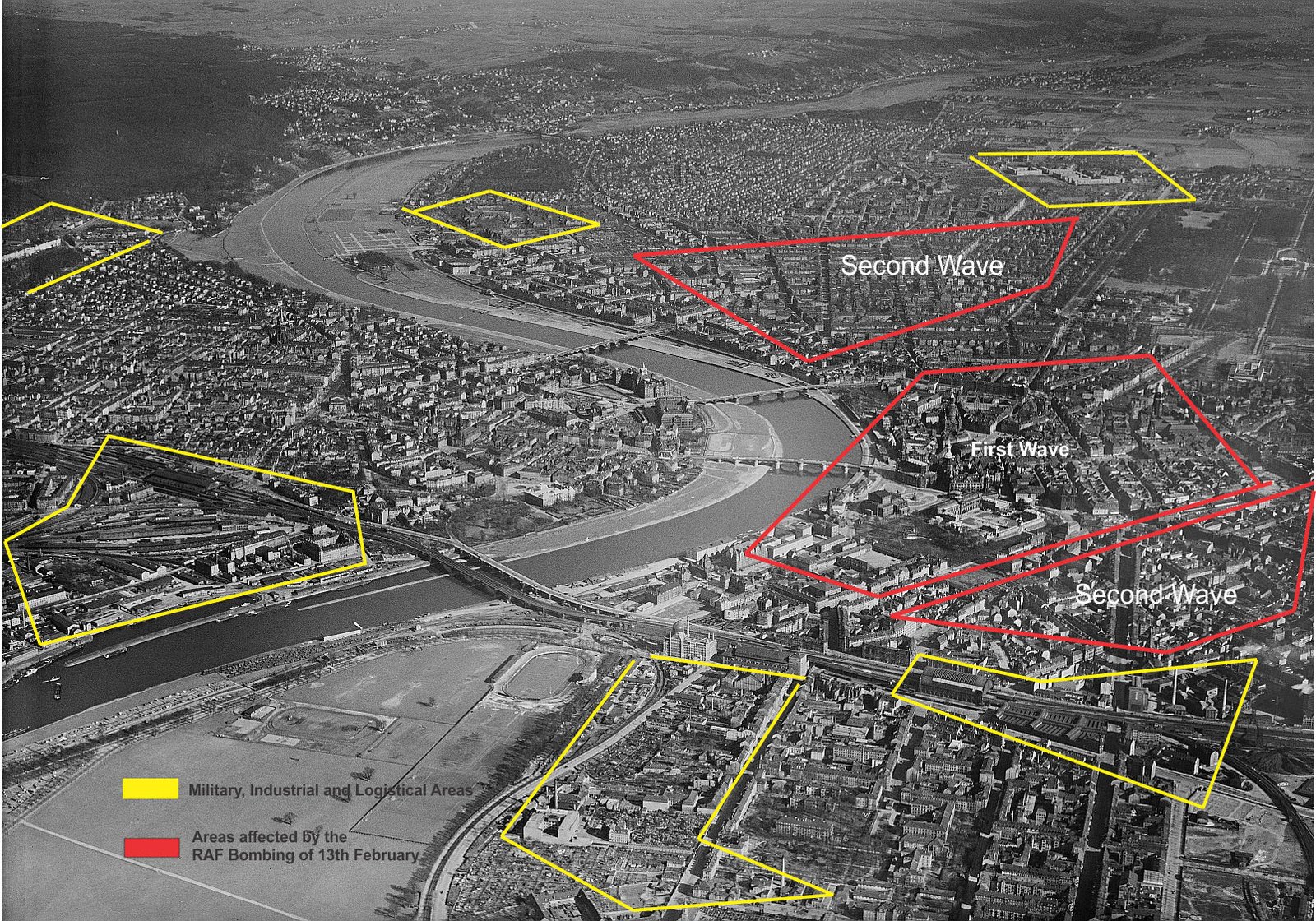

On the night of February 13th nearly 800 RAF bombers struck the city. Their aiming point was a stadium in the city centre, and the bomb load was predominantly incendiaries—some 650,000 of them.

The attack created a firestorm that obliterated the city’s historic Baroque heart and killed an estimated 25,000 people.

The American role came the next day.

On February 14th and 15th, waves of USAAF B-17s, numbering over 500 aircraft in total, attacked Dresden in broad daylight. Their designated targets were the railway marshalling yards on the city’s edge, in keeping with their precision-bombing doctrine.

By the time they arrived, however, the city was a raging inferno, shrouded in a pall of smoke that stretched for thousands of feet into the sky. Pinpoint accuracy was impossible. The American bombs, aimed at the yards, inevitably fell into the burning chaos of the city proper, contributing to the overall destruction.

The immediate effect was not a German outcry, which was expected, but a profound shock among the Western Allies.

An Associated Press correspondent, covering a briefing at Allied Headquarters, quoted an RAF intelligence officer who bluntly stated that the Allies were now engaged in a strategy of “deliberate terror-bombing of German population centres as a ruthless expedient of hastening Hitler’s doom.”

The publication of this quote caused a firestorm of its own, particularly in the United States, where the public had been conditioned to believe its air force was fighting a different, more moral war. The distinction between precision strikes and area bombing, so carefully maintained in public messaging, had evaporated in the flames of Dresden.

This moral crisis was immediately complicated by another, far grimmer revelation.

As Allied ground forces pushed into Germany, they began to liberate the Nazi concentration camps, exposing a level of industrialized horror that stunned the world. The newsreel footage of skeletal survivors and heaps of corpses hugely revived public anger against Germany.

For many, in this mood of righteous fury, the obliteration of a German city, no matter how beautiful or historic, seemed not a crime but a just and fitting punishment.

Even so, the disquiet lingered at the highest levels. Prime Minister Winston Churchill, who had initially urged action to support the Soviets, began to have serious second thoughts about the nature of the campaign he had unleashed.

On March 28th, 1945, he wrote a memorandum to the Chiefs of Staff that revealed his deep unease. “It seems to me that the moment has come when the question of bombing German cities for the sake of increasing the terror, though under other pretexts, should be reviewed,” he wrote. “Otherwise we shall come into control of an utterly ruined land… The destruction of Dresden remains a serious query against the conduct of Allied bombing.”

His words were a startling admission from the war’s most defiant leader, a recognition that in the final, brutal stages of the conflict, the carefully constructed moral and strategic justifications for the bombing campaign had begun to crumble under the weight of their own terrible success.

–

The Question Of War Crimes

“In the first place, it is against international law to bomb civilians as such and to make deliberate attacks upon civilian populations. That is undoubtedly a violation of international law. In the second place, targets which are aimed at from the air must be legitimate military objectives and must be capable of identification. In the third place, reasonable care must be taken in attacking these military objectives so that by carelessness a civilian population in the neighbourhood is not bombed.”

British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain in the House of Commons on June 21st 1938

To pass judgment on the Allied strategic bombing campaign of the Second World War is to navigate a landscape of profound moral complexity, where the imperatives of total war clash with the foundational principles of civilised conduct.

Two things must be stated at the outset.

First, there is no moral equivalence between the Allied bombing and the singular evil of the Nazi regime. The campaign, which claimed the lives of an estimated 800,000 German and Japanese civilians, was waged to defeat a genocidal aggressor responsible for the deaths of tens of millions.

The murder of six million Jews in the Holocaust was an act of industrialized racist extermination; the bombing of cities was an act of war aimed at breaking an enemy’s ability and will to fight. The distinction in intent and scale is an abyss.

Second, the campaigns were conducted with the overwhelming support of the British and American publics, for whom the nightly raids were seen as righteous and necessary retribution. The aircrews flew with the backing of their nations.

Yet, these truths do not absolve the bombing of scrutiny.

The staggering figure of civilian dead, and the untold suffering of the maimed, traumatised, and homeless, demands its own moral accounting, separate from the crimes of its enemies.

To dismiss the question as merely a philosophical debate is to evade a history written in fire and ash.

The core of that debate lies in the ancient and enduring concept of the ‘just war’.

The theory, first given clear articulation by St. Augustine and later refined by St. Thomas Aquinas, divides the question of war’s legitimacy into two distinct parts. The first is jus ad bellum, the just cause for going to war.

By this measure, the Allied struggle against Nazi Germany is perhaps the 20th century’s most unambiguous example of a just and necessary conflict.

The second, and far more troubling question, is that of jus in bello: the just and moral conduct of that war.

It is here that the Allied campaign falters.

The principles of jus in bello hinge on two inviolable tenets: proportionality, which dictates that the means used must be proportional to the military ends sought; and distinction, which demands that a belligerent must, at all times, distinguish between combatants and non-combatants.

The Latin root of “innocent” is in-nocens—literally, “one not engaged in harmful activity.”

This principle imposes an absolute obligation not to make non-combatants the intended object of an attack.

The quest to codify these moral principles into law has been a long and arduous one.

Its first great theorist, the 17th-century Dutch philosopher Hugo Grotius, was so horrified by the barbarity of the Thirty Years’ War that he dedicated himself to creating a framework for international law, writing, “I saw in the whole Christian world a license of fighting at which even barbarous nations might blush.”

Yet for centuries, little progress was made.

As a sagacious Roman observed, inter arma silent leges—in time of war, the laws are silent.

It was not until the industrialisation of slaughter in the 19th and early 20th centuries that the first real attempts at codification were made. The Geneva Convention of 1864 protected wounded soldiers, and the Hague Conferences of 1899 and 1907 attempted, for the first time, to restrict warfare, specifically prohibiting the bombardment “by whatever means, of towns, villages, dwellings, or buildings which are undefended.”

This pre-war legal framework was, however, tragically inadequate for the realities of total aerial warfare.

A legalistic defence of the Allied area bombing could argue, as it did at the time, that its provisions were not strictly violated.

German cities were not “undefended”—they were protected by rings of lethal flak batteries and squadrons of night-fighters.

Their populations, one could claim, had been amply warned by leaflet drops and broadcasts.

Yet such an argument eviscerates the entire spirit and purpose of the law. As Cicero noted centuries earlier, one must consider not what the utmost rigour of the law allows, but what is becoming of one’s character.

The Hague Conventions, however flawed, were an attempt to uphold the principle of distinction. Area bombing was a strategy predicated on its complete annihilation.

The ultimate legal paradox arose after the war, at the International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg.

There, the victorious Allies established a charter to prosecute Nazi leaders for an unprecedented catalogue of atrocities. The central challenge was the principle against ex post facto law—the creation of laws after the commission of the crimes they define. To overcome this, the Tribunal argued that it was simply applying principles of justice already latent within international treaties and the domestic laws of all civilized nations.

Two of the four crimes specified in the Nuremberg Charter are profoundly relevant to the bombing campaign.

Article 6(c) defined “Crimes Against Humanity” as “inhumane acts committed against any civilian population.”

Article 6(b) designated as a War Crime the “wanton destruction of cities, towns, or villages, or devastation not justified by military necessity.”

If the Allies were to be tried by the standards of their own tribunal, their position would be indefensible. Article 6(c) applies, without qualification, to a campaign that deliberately targeted civilian population centres. The only defence against Article 6(b) rests entirely on the ambiguous pillar of “military necessity.”

Here, the principle of proportionality becomes the judge.

Was the obliteration of a city a proportionate response to destroy a factory within it?

Dropping thousands of tons of bombs on the historic heart of Hamburg to destroy its shipyards, or firebombing Tokyo to hit its small, dispersed workshops, is, to borrow a powerful analogy, akin to chopping off a man’s head to cure his toothache.

This is before we consider the publicly avowed intent of the campaign’s architects, who stated plainly that their goal was the destruction of civilian morale—a clear admission of targeting the non-combatant population itself.

The defence of tu quoque (“you also”), rightly rejected by the tribunal for the German defendants, offers no moral sanctuary; the crimes of the enemy do not license one to commit them in return.

The true judgment on the bombing campaign was not rendered at Nuremberg, but was written, slowly and deliberately, into the international law that emerged from the war’s ashes.

The moral culpability of area bombing was so implicitly understood that it became the silent impetus behind the landmark Fourth Geneva Convention of 1949, designed explicitly for the protection of civilians in time of war. But the convention’s chief architects—Britain and the United States—ensured that no specific wording explicitly outlawing their own recent practices was included.

It took another generation, until 1977, for the law to finally and unequivocally catch up with morality. The first Additional Protocol to the Geneva Convention at last codified what had been morally clear for decades.

Its articles, now the bedrock of international humanitarian law, explicitly forbid: direct attacks against civilians or civilian objects; indiscriminate attacks that fail to distinguish between military and civilian targets; and attacks where the expected civilian casualties would be clearly excessive—disproportionate—in relation to the anticipated military advantage.

Had this protocol been in force during the Second World War, the British and American architects of the area-bombing campaign would have been liable for prosecution as war criminals.

Its passage stands as history’s retrospective and damning verdict.

–

Conclusion

“To praise a historian for his accuracy is like praising an architect for using well-seasoned timber or properly mixed concrete in his building. It is a necessary condition of his work, but not his essential function.”

British historian E.H. Carr

In the final analysis, we are left with a series of questions whose answers are as clear as they are uncomfortable.

Was area bombing necessary to win the war?

No.

Despite the devastation, German industrial production continued to rise until mid-1944, and was crippled in the end not by area bombing but by the targeted, precision attacks on oil and transportation networks.

Was it proportionate?

No.

The firebombing of Dresden and Tokyo, and the atomic annihilation of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, represent the very definition of disproportionate force.

Was it against the humanitarian and moral principles that civilisation has struggled for centuries to establish?

Yes.

It contravened every tenet of just war theory from Aquinas to Grotius.

Was it, in the strictest juridical sense of the time, a “war crime”?

Perhaps not.

The principle of nullum crimen sine lege—no crime without a law—means the absence of a specific, pre-existing statute offers a narrow legal defence.

But this is a defence of profound moral cowardice.

The absence of a law forbidding an act does not make that act right, especially when it violates foundational principles of humanity recognised for centuries.

Immanuel Kant argued forcefully that it is never right to do evil in the pursuit of good. The bombing campaign was a five-year-long refutation of that principle, an enterprise that accepted the terrorising and killing of hundreds of thousands of non-combatants as a necessary tool of victory.

The precision raids on oil refineries, V-weapon sites, and U-boat pens were legitimate acts of war, whose tragic civilian cost can be defended under the harsh doctrine of military necessity.

But the deliberate targeting of entire cities cannot. It was not a side-effect of war; it became the very method of war.

The Allied area-bombing campaign was not, therefore, a legal crime by the insufficient standards of its time.

It was, however, a moral crime, and its legacy remains a harrowing testament to the capacity of even a just war to descend into a terrifying darkness.

***

If you’ve enjoyed reading this article, consider booking one of our private guided tours of Berlin.

Bibliography

Andreas‑Friedrich, Ruth (1989), Berlin Underground, 1938‑1945, Paragon House, ISBN 978‑1557781598.

Corrigan, Gordon (2006), Blood, Sweat and Arrogance: The Myths of Churchill’s War, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, ISBN 978‑0‑297‑84628‑0.

Crew, David F. (2020), Bodies and Ruins: Imagining the Bombing of Germany, 1945 to the Present, University of Michigan Press, ISBN 978‑0‑472‑13013‑9.

Grayling, A. C. (2006), Among the Dead Cities: Is the Targeting of Civilians in War Ever Justified?, Bloomsbury Publishing, ISBN 978‑0‑7475‑7673‑1.

Kershaw, Ian (2007), Fateful Choices: Ten Decisions that Changed the World, 1940–1941, Penguin Books, ISBN 978‑0‑14‑101418‑0.

Koonz, Claudia (2003), The Nazi Conscience, Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, ISBN 978‑0‑674‑01172‑8.

Macksey, Kenneth (2000), Military Errors of World War Two, Cassell Military Paperbacks, ISBN 978‑0‑304‑35577‑4.

Middlebrook, Martin (1988), The Berlin Raids: RAF Bomber Command Winter 1943–44, Cassell Military Paperbacks, ISBN 978‑0‑304‑35280‑3.

Overy, Richard (2013), The Bombing War: Europe 1939–1945, Penguin Books, ISBN 978‑0‑14‑100321‑4.

Sebald, W. G. (2003), On the Natural History of Destruction, Modern Library, ISBN 978‑0‑375‑75526‑7.

HISTORICAL ARTICLES

Mythbusting Berlin

Could The Western Allies Have Captured Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

To contemplate a Western Allied capture of Berlin in 1945 is to challenge the established endgame of the Second World War. What was the true military and logistical feasibility of a Western Allied assault on the Nazi capital? What factors truly sealed Berlin’s fate, and what might have changed had the Allies pushed eastward?

Answering these questions means delving into the complex interplay of logistics, political maneuvering, and the competing visions for a post-war world

Did Any Of The Rothschild Dynasty Die In The Holocaust? – Mythbusting Berlin

The Rothschild name is synonymous with immense wealth, influence, and persistent conspiracy theories—especially during the era of Nazi Germany. Often targeted by antisemitic propaganda, the family’s survival during World War II has sparked myths about their supposed immunity from Nazi persecution. But did any Rothschild family member actually perish in the Holocaust? This article explores that compelling question, unraveling historical misconceptions and revealing the reality behind one of Europe’s most famous dynasties.

Did Frederick The Great Introduce The Potato To Germany? – Mythbusting Berlin

One of the more bizarre claims to fame attributed to the first King of Prussia is that the man who would go down in history known as Frederick the Great introduced the potato to Germany during his reign back in the 1700s. This starchy root vegetable has undoubtedly become a staple part of German cuisine – an essential addition to any plate of Schnitzel, Schweinshaxn, and Königsberger Klopse – however, whether Frederick the Great is

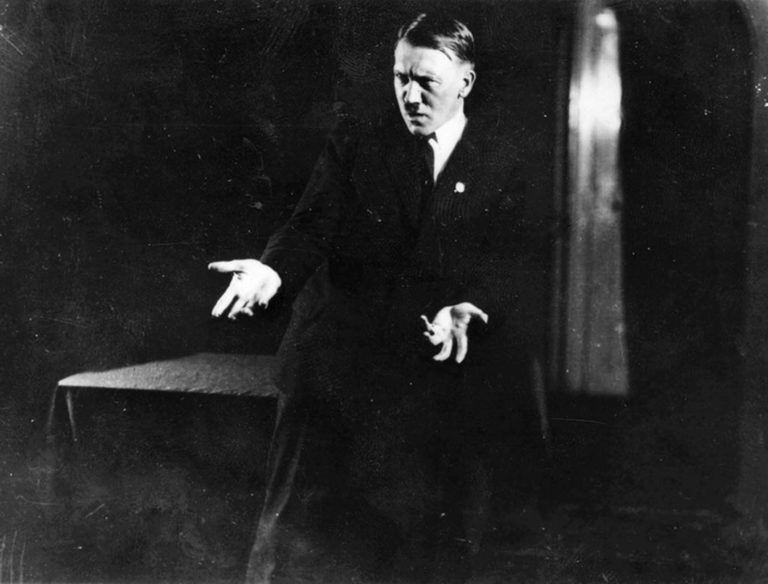

Did Hitler Escape To Argentina In 1945? – Mythbusting Berlin

Although Nazi leader, Adolf Hitler, certainly remains an inescapable figure, could there be any truth to the story of his escape to Argentina in 1945? That the most wanted man on earth could simply vanish, to spend the rest of his life peacefully in South American obscurity captivates imaginations. Yet, despite numerous investigations, this tale persists primarily as myth—fueled by speculation, hearsay, and conspiracy theories.

Did The Nazis Invent Decaf Coffee? – Mythbusting Berlin

Persistent rumors claim that Nazis preferred their coffee anything but pure, leading some to wonder if they might have influenced the development of decaffeinated coffee. Although decaf was already widely available across Europe by the mid-20th century, speculation continues: could the Nazis really have played a role in popularizing—or even discovering—this caffeine-free alternative, or is this simply another caffeinated conspiracy cooked up to sensationalize an ordinary historical detail?

Did The Nazis Invent The Bicycle Reflector? – Mythbusting Berlin

The fruits of wartime ingenuity are plenty – so many, in-fact, that it has become somewhat of a worn cliche that as the guns start firing the innovators get to work, often solving problems while providing more problems for the enemy to overcome.The kind of progress that results in the production of newer improved, more lethal weapons, such as to increase the chances of victory.

Did The Nazis Run The Largest Counterfeiting Operation In History – Mythbusting Berlin

During the Second World War the Nazis masterminded an astonishing plot to destabilise Britain by flooding its economy with counterfeit banknotes. Crafted in secret by concentration camp prisoners, this forged fortune became the most ambitious counterfeiting operation ever attempted. But was it history’s largest? Dive into the extraordinary tale of Operation Bernhard,

rife with deception, survival, and intrigue—revealing the truth behind one of the Third Reich’s most audacious schemes and its surprising legacy.

Did The Second World War End In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

When is a war ever truly over? When the last shot is fired in anger would seem like the best measure. Rarely, though, is it possible to gain insight into such a moment.

Remarkably, a record still exists of such a moment at the end of the First World War on the Western Front. A seismic register and recording of the last belching battery of British guns firing artillery across no-man’s-land, followed by a profound

Did The Spanish Flu Pandemic Help The Nazis Take Power? – Mythbusting Berlin

The devastating Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918-1919 struck amid Germany’s post-war turmoil, compounding social instability, economic hardship, and widespread political disillusionment. Could this catastrophic health crisis have indirectly paved the way for Nazi ascension? While often overshadowed by war and revolution, the pandemic’s profound psychological and societal impacts arguably contributed to the perfect storm, enabling extremist ideologies—including Nazism—to gain popularity and ultimately seize power in a fractured Germany.

How Old Is Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

A relatively new arrival in Europe, Berlin is over 1000 years younger than London, nevermind Rome or Athens, Jerusalem or Jericho. Just how old is Berlin though?

A question fraught with false assumptions and distortions – that has more often than not been answered with propaganda as it has with the cold hard truth.

Was Adolf Hitler A Drug Addict? – Mythbusting Berlin

Solving the enigma of the ‘Führer’ has become a preoccupation for many, since the arrival of the Austrian-German onto the world stage – although moving beyond the mythology without falling into the trap of prejudically extrapolating on the psychopathography of Hitler or demonising so as to excuse his actions has proven problematic. What to make of the man who became more than the sum of his masks? The painter; the military dilettante, the mass murderer,

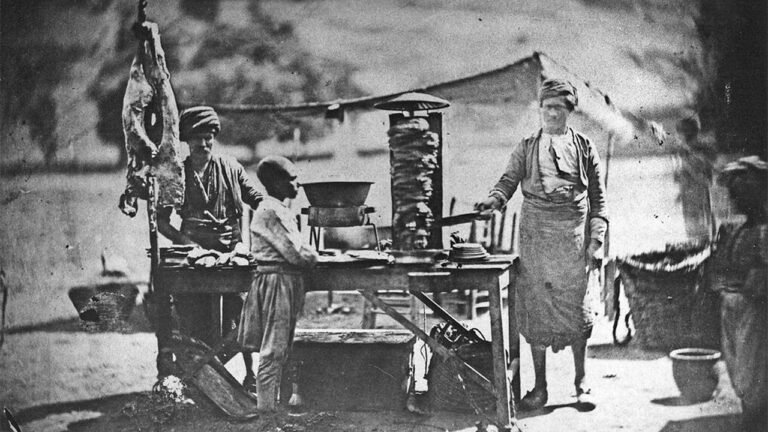

Was Currywurst Invented In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

Explore the story behind what many consider Berlin’s most iconic snack—the ever-so-humble Currywurst. Often hailed as an enduring symbol of culinary creativity amid Cold War scarcity, this humble dish has inspired fierce debate about its true origin. But was it genuinely invented here in Berlin, or have proud locals simply adopted and elevated this spicy street-food favorite into legendary status all their own?

Was Fanta Invented By The Nazis? – Mythbusting Berlin

As one of the most secretive organisations in the world, the Coca Cola corporation refuses to share its secret recipe with anyone. Famously insisting only on shipping the base syrup of its drinks to plants around the world to be carbonated and distributed.

This combined with the trade limitations of the Second World War may have led to the introduction of one of the most popular soft-drinks in the world. But could it be true:

Was Frederick The Great Gay? – Mythbusting Berlin

Frederick II of Prussia, better known as Frederick the Great, is often remembered as the archetypal enlightened monarch – a brilliant military commander, patron of the arts, and learned philosopher. Yet behind the stern portraits of this 18th-century warrior-king lies a personal life long shrouded in intrigue and speculation. Intrigue around the king’s sexual orientation has persisted through the centuries, chiefly revolving around one question: Was Frederick the Great gay?

Was Henry Ford A Nazi? – Mythbusting Berlin

US auto tycoon, Henry Ford, holds the ignominious distinction of being the only American Adolf Hitler praised by name in his National Socialist manifesto: ‘Mein Kampf’. This was not, as it turns out, the only connection between Ford and the Party of Hitler, Himmler, and the Holocaust.

Ford’s overt affinity with the Third Reich reveals a troubling past. How deep these connections ran, and how consequential they were for both sides, is a chapter

Was The Colour Blue Invented In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

Tracing the true history of blue—from ancient Egyptian dyes to the accidental discovery of Prussian Blue in a Berlin lab. We’ll debunk myths about seeing blue, explore colonial indigo plantations, scale mountains with a cyanometer, and trace Van Gogh’s starry skies—all to answer one question: how did Berlin shape our understanding of the world’s rarest color?

Was The Döner Kebab Invented In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

Unlikely icon of immigrant success; fast food symbol of the working class; over-hyped midnight disco eat; or culturally appropriated cuisine? Its influence goes far beyond layers of seasoned meat and fresh vegetables stuffed into pita bread. But does Berlin deserve credit as the Döner Kebab’s true birthplace, or has the city merely refined and popularized a culinary tradition imported from elsewhere?

Was The Fall Of The Berlin Wall An Accident? – Mythbusting Berlin

On a seasonally crisp night in November 1989, one of the most astonishing events of the 20th century occurred. After twenty eight years, three months, and twenty eight days of defining and dividing the German capital, the Berlin Wall ceased to exist – at least in an abstract sense. Although the removal of this symbol of the failure of the East German system would take some time, its purpose – as a border fortification erected

Was The Nazi Party Democratically Elected? – Mythbusting Berlin

The myth persists that Adolf Hitler rose to power through popular democratic choice. Yet history reveals a darker, more complicated truth. Hitler’s ascent involved exploiting democratic institutions, orchestrating violence, propaganda, and political intrigue—not a simple election victory. Understanding how Germany’s democracy collapsed into dictatorship helps illuminate the dangerous interplay between public desperation, elite miscalculations, and extremist ambition, providing crucial lessons for safeguarding democracy today.

Were The Allied Bombings Of Germany War Crimes?

The history of the Allied bombing of Germany during the Second World War still triggers fierce debate. Was reducing cities to rubble a necessary evil – justice from above in a just war – or an unforgivable crime? Can the intentional targeting of civilians ever be justified as militarily necessary?

In a conflict where all rules seemed to vanish, an even more pertinent question persists: by the very standards they would use to judge their