“No one gave the salute a second thought for fifty years. It was simply what one did… The meaning of a gesture, however, is not fixed. It is contingent, contextual, and contestable.”

Richard J. Ellis, To the Flag: The Unlikely History of the Pledge of Allegiance

The classroom is silent, save for the rhythmic chant of young voices. Rows of children, scrubbed and neat, stand beside their wooden desks, their eyes fixed on the flag at the front of the room.

At a signal from the teacher, right arms shoot forward, angled slightly upward, palms down. The children’s faces are earnest, their voices clear as they recite the daily pledge, a promise of loyalty to their nation and its ideals.

A scene of disciplined patriotism, a ritual of unity and belonging. Anyone could be forgiven for picturing a schoolhouse in 1930s Bavaria, the air thick with the nascent fervor of the Third Reich.

But they would be wrong.

The year is 1892, and this classroom is not in Germany, but in the United States of America.

Here the gesture that would one day become infamous as the ‘Nazi salute’ exists as a seemingly innocuous, patriotic, American counterpart.

Known as the ‘Bellamy Salute’ for fifty years it was how millions of American children greeted their flag.

–

The Bellamy Salute

“The case of the Bellamy Salute shows in a particularly poignant way how a gesture, once created, can take on a life of its own… It demonstrates that a symbol’s meaning is not inherent in its form, but is imposed upon it by those who use it and by those who observe it.”

Martin M. Winkler, author of ‘The Roman Salute: Cinema, History, Ideology’

The story of the Bellamy Salute begins with a magazine and a marketing campaign.

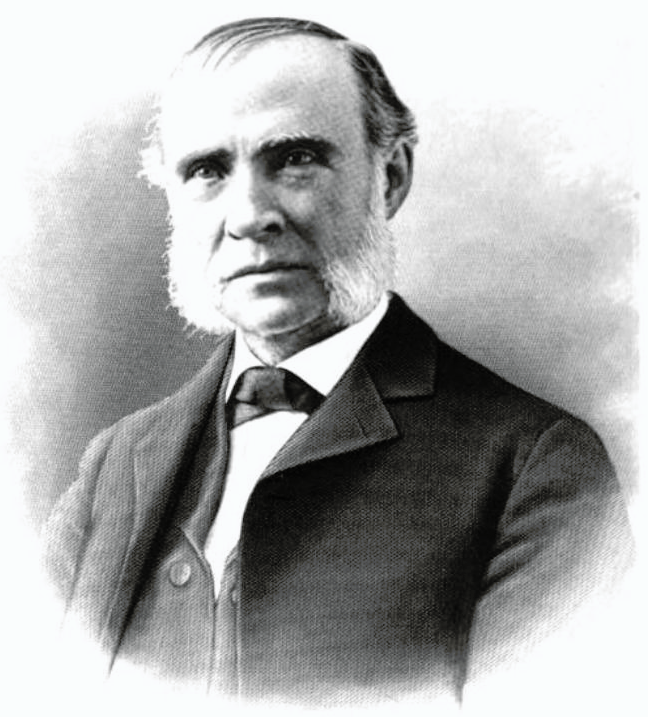

In the late 19th century, Daniel Sharp Ford, the owner of the popular Boston-based family magazine The Youth’s Companion, launched a nationwide drive to place an American flag in every schoolhouse. Ford, a canny marketer, saw this as a way to sell flags and subscriptions, but he also genuinely believed in the project’s civic value.

The American Civil War was still a raw, living memory, and Ford felt that a daily ritual of patriotic devotion could help knit the still-fragile nation back together.

To accompany the flags, Ford commissioned one of his writers, a Baptist minister and Christian socialist named Francis J. Bellamy, to compose a short, stirring pledge. The result, published in the September 8th 1892, issue of the magazine, was the original Pledge of Allegiance: “I pledge allegiance to my Flag and the Republic for which it stands; one Nation indivisible, with Liberty and Justice for all.”

But words alone were not enough. Bellamy and his editor, James B. Upham, felt that a physical gesture was needed to give the pledge the appropriate gravity and theatrical flair. It was Upham who, upon reading the pledge, reportedly clicked his heels together, stood at attention, and declared, “Now up there is the flag; I come to salute.” He then demonstrated the motion: as one began the pledge, the right hand was to be brought up in a military-style salute to the forehead. Then, at the words “to my Flag,” the arm was to be gracefully extended forward, palm up, toward the flag, and held there until the pledge was complete.

This became the Bellamy Salute.

Bellamy and his friends convinced President Benjamin Harrison to issue Presidential Proclamation 335, which required all schoolchildren across the United States to swear the Pledge of Allegiance using this salute. Its official debut came on October 12th 1892, when some 12 million American schoolchildren recited the pledge and performed the salute to commemorate the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’s arrival in the Americas.

For decades, the gesture was an unremarkable part of American civic life, a familiar ritual for generations of students.

The trouble, of course, began across the Atlantic. In the 1920s and 1930s, new political movements were rising in Europe, movements that placed a heavy emphasis on theatricality, mass rallies, and symbols of absolute loyalty.

In Italy, Benito Mussolini’s Fascists adopted a straight-armed salute, claiming it was a revival of an ancient Roman custom. Shortly after, in Germany, Adolf Hitler’s burgeoning Nazi Party adopted a nearly identical gesture.

By the mid-1930s, the visual similarity was becoming deeply uncomfortable for many Americans.

The sight of their children saluting the flag with a gesture now synonymous with European dictatorships was jarring. Fears grew that photographs and newsreels of American children performing the Bellamy Salute could be used as propaganda by the fascist regimes, edited to suggest American support for their cause.

Anti-interventionists in the U.S., like the famed aviator Charles Lindbergh, were smeared by opponents who used images of them performing the once-innocuous salute to imply Nazi sympathies.

As the world edged closer to war, the pressure to abandon the salute mounted. School boards began to alter the gesture on their own initiative, but some patriotic groups, like the Daughters of the American Revolution, resisted, arguing that an American tradition should not be changed just because foreign powers had adopted a similar one.

The final blow came after the attack on Pearl Harbor and America’s entry into the Second World War following the declaration of war on the country by Adolf Hitler. With the nation now at war with the very regimes whose salute so closely mirrored its own, the use of the Bellamy Salute became ironic and untenable.

And yet, on June 22nd 1942, the United States Congress officially codified the Pledge of Allegiance for the first time, still including a description of the Bellamy Salute. Section 7 of Public Law 77-623 would state:

“That the pledge of allegiance to the flag, ‘‘I pledge allegiance to the flag of the United States of America and to the Republic for which it stands, one Nation indivisible, with liberty and justice for all’’, be rendered by standing with the right hand over the heart; extending the right hand, palm upward, toward the flag at the words ‘‘to the flag’’ and holding this position until the end, when the hand drops to the side.”

Soon the public controversy became too great to ignore.

Six months later, on December 22nd 1942, Congress amended the Flag Code, forever abolishing the extended-arm gesture and stipulating that the pledge should “be rendered by standing with the right hand over the heart.”

The Bellamy Salute, born of post-Civil War patriotism, had died a victim of its unfortunate resemblance to the signature gesture of 20th-century tyranny.

–

Benito Mussolini & The Roman Salute

“We have created our myth. The myth is a faith, a passion. It is not necessary that it shall be a reality…”

Benito Mussolini

The beginning of the end of the Bellamy salute came not in 1930s Germany but in the Italy of the 1920s, where a nearly identical gesture was being deliberately and powerfully woven into the fabric of a new political identity.

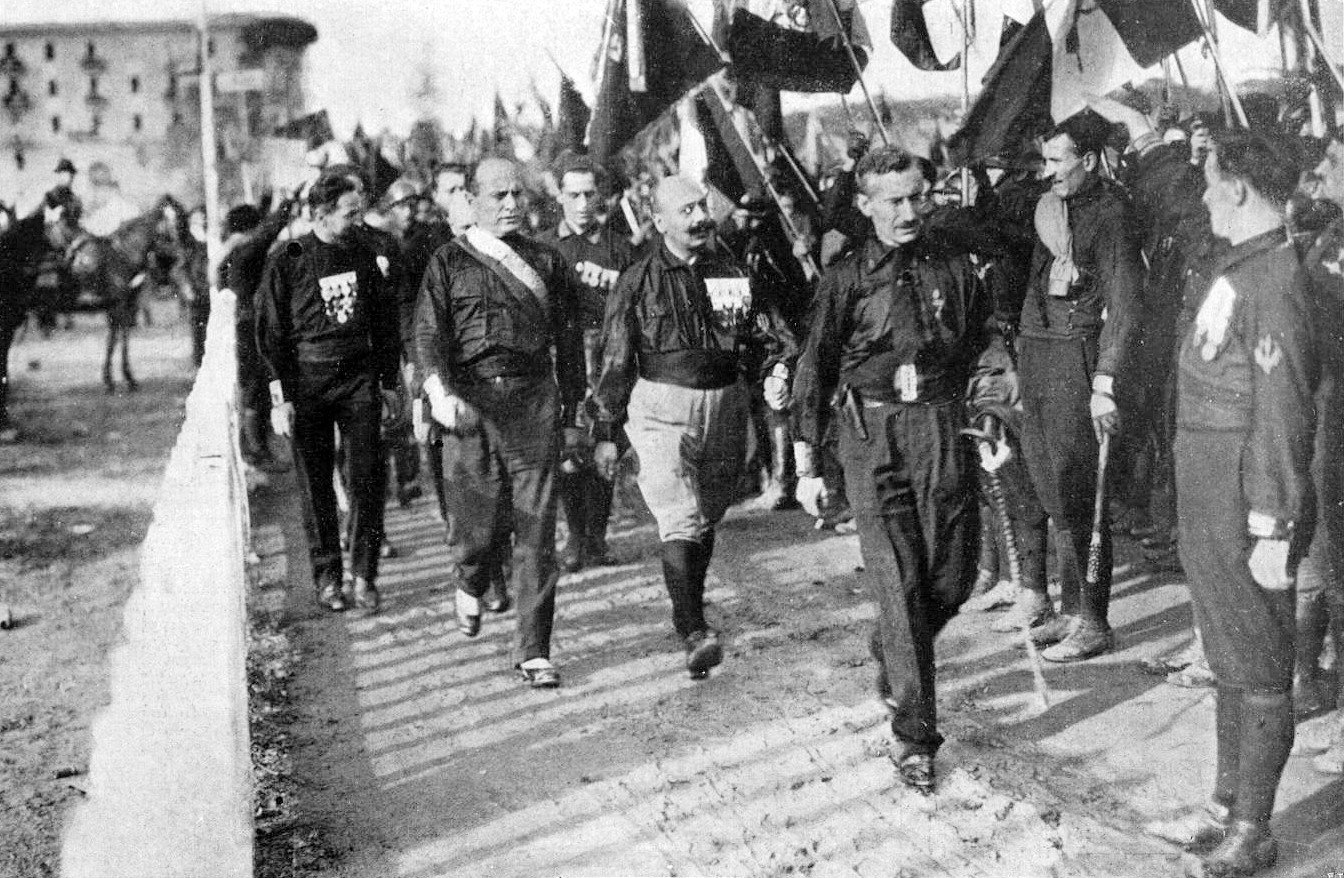

Benito Mussolini, a former journalist and socialist turned firebrand nationalist, understood the power of symbols. As he forged his Fascist movement in the chaotic aftermath of the First World War, he sought to create a new Italian identity, one that rejected the perceived weakness of liberal democracy and embraced a vision of strength, discipline, and national glory.

To do this, he reached back into the annals of history, seeking to cloak his modern political project in the grandeur of ancient Rome.

His most visible and potent symbol was the saluto romano, the Roman salute. Performed by his black-shirted paramilitary squads, the Squadristi, the stiffly outstretched arm was meant to be a direct link to the legions and emperors of the past. It was a gesture of power, of imperial ambition, a physical manifestation of Mussolini’s promise to restore Italian greatness.

The Blackshirts, initially organized in 1919 to violently suppress socialists and other political opponents, used the salute, along with their distinctive uniforms and the ancient Roman symbol of the fasces (a bundle of rods with an ax), to build a brand of intimidating authority.

By the time of the 1922 March on Rome, which brought Mussolini to power, the salute was an inseparable part of the Fascist identity, a mandatory public gesture of loyalty to Il Duce.

But here lies the central myth. Was this salute truly Roman? The historical evidence says no. There are no descriptions in Roman literature of a stiff, straight-armed salute being used as a common greeting or sign of respect.

Roman art, from the friezes of Trajan’s Column to imperial statues, shows various gestures of greeting, blessing, or acclamation, but none match the precise, rigid form adopted by the Fascists. Roman soldiers may have hailed their commanders, and civilians may have raised a hand to an emperor, but it was likely with a bent arm and an open palm, more akin to a modern wave than the sharp gesture of the 20th century.

So, if not from ancient Rome, where did Mussolini’s ‘Roman Salute’ actually come from?

The answer, ironically, lies not in the ruins of the Forum but in the art galleries and theaters of post-Renaissance Europe.

The true genesis of the gesture can be traced to a single, explosive work of art: the 1784 painting The Oath of the Horatii by the French neoclassical master Jacques-Louis David.

The painting depicts a dramatic moment from a Roman legend in which three brothers swear an oath to their father to defend Rome to the death. The painting is based on an ancient Roman legend that is best known today in the version told by the Roman historian Titus Livius (lived c. 59 BCE – c. 17 CE) in his Ab Urbe Condita 1.23–26.

The cities of Rome and Alba Longa were at war, but they wanted to minimize the number of casualties, so they agreed to an arrangement that each city would select three champions who would fight the other city’s champions to the death.

The Romans selected a set of triplet brothers with the family name Horatius (the plural form of which is Horatii). The people Alba Longa selected a set of triplet brothers with the family name Curiatius (the plural form of which is Curiatii). When these two sets of triplets came together to fight, the Curiatii killed two of the Horatii almost immediately, but the Curiatii were all injured in the fight, leaving them weakened so that the single remaining Horatius, who was uninjured, was able to fight them one-by-one and slay them all, leading Rome to victory over Alba Longa.

In David’s work the brother’s arms are outstretched, rigid and determined, in a gesture of unwavering civic virtue and individual sacrifice.

Note, however, that none of the brothers in the Oath of the Horatii are making the exact salute that Mussolini’s fascists performed in the twentieth century.

The brother in the painting who is closest to the viewer has his arm almost perfectly horizontal, not raised in the air. Meanwhile, the brothers in the middle and back—who do have their arms raised—are saluting with their left arms, rather than their right.

Nevertheless, the painting was a sensation, becoming an icon of the French Revolution and cementing the image of the straight-armed salute as a symbol of patriotic, republican Rome in the popular imagination.

This artistic invention, this “fakelore,” was then amplified by 19th and early 20th-century stage plays and, crucially, the new medium of cinema.

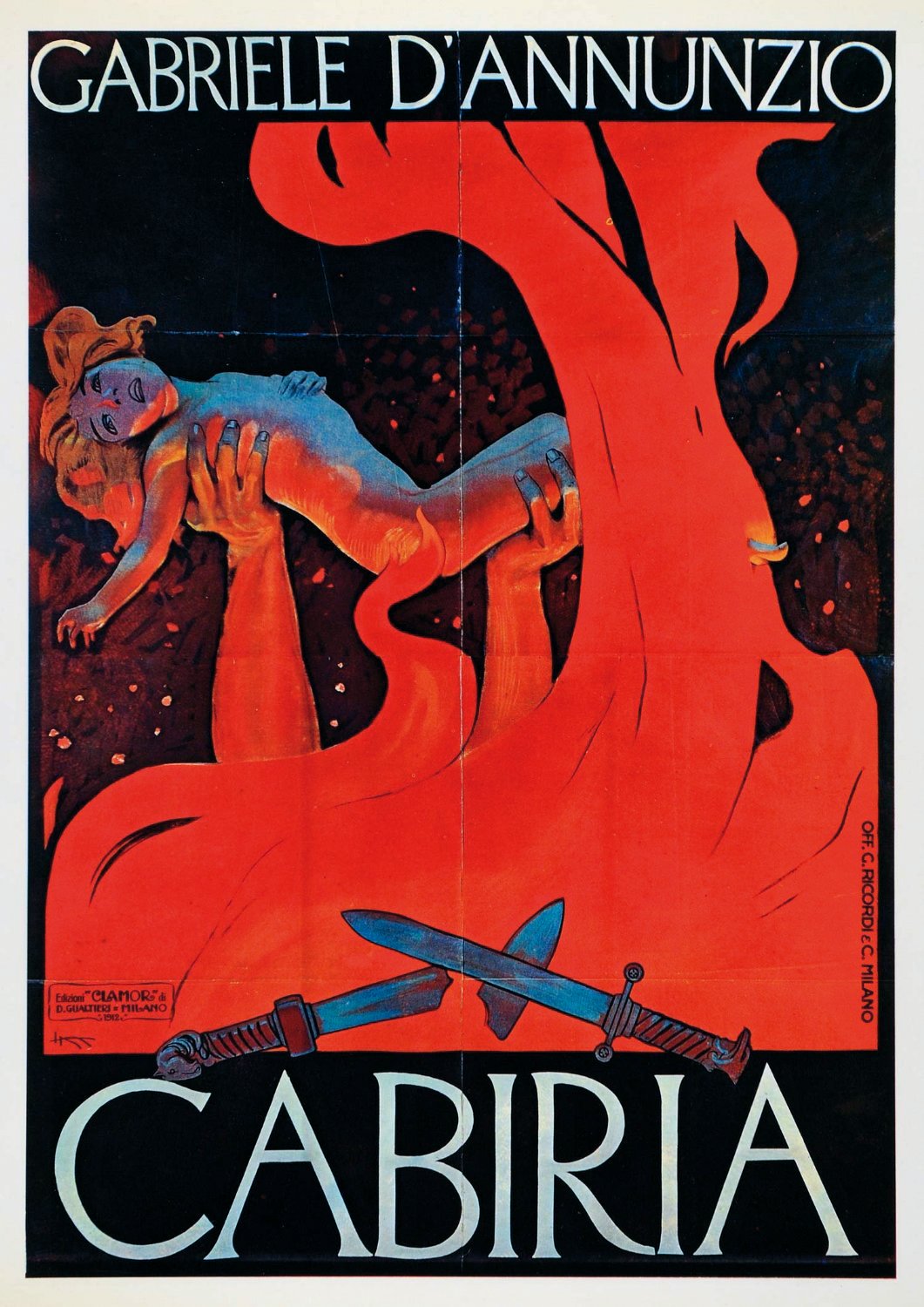

Historical epics like the 1914 Italian silent film ‘Cabiria’ depicted characters making the salute, presenting this piece of artistic license as historical fact.

The man who wrote the intertitles for Cabiria (and the names of the characters and the name of the film itself) was none other than Gabriele D’Annunzio, a flamboyant poet, ultra-nationalist, and political firebrand who would become a key influence on Benito Mussolini.

In 1919, D’Annunzio led a legion of nationalist veterans to occupy the disputed city of Fiume (now Rijeka in Croatia), establishing his own proto-fascist city-state.

It was here that he, as the self-proclaimed Duce, perfected the political theater that Mussolini would later adopt on a national scale. He harangued crowds from balconies, instituted elaborate ceremonies, and made the ‘Roman salute’, which he had helped popularise in Cabiria, a centerpiece of his neo-imperial ritual.

Mussolini, a master of political appropriation, saw the power in D’Annunzio’s theatrics.

He adopted the title of Duce, the black shirts, and, most importantly, the salute. He took an 18th-century French painter’s vision of Roman virtue, filtered through the lens of early cinema and the eccentricities of a nationalist poet, and sold it to the Italian people as a direct, unbroken link to their imperial ancestors. The Mussolini salute was not a revival of an ancient tradition; it was the invention of a modern one, a powerful piece of political branding that successfully mythologized the past to serve the ambitions of the present.

It would take the rise of another regime – directly influenced by Mussolini’s March on Rome and seizure of power – to irreversibly condemn the raised right arm salute to an eternity of infamy, forever transforming it from a piece of political theatre into the universal symbol of totalitarian oppression.

–

The Hitlergruß

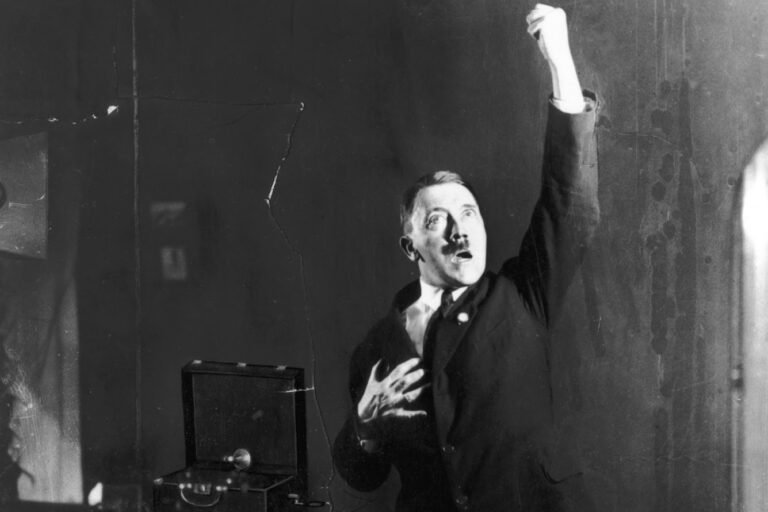

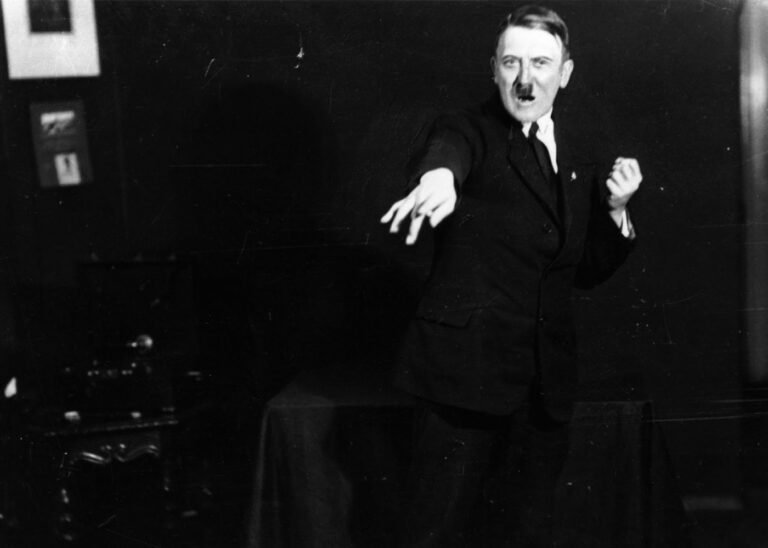

“In the days of Frederick the Great, people still saluted with their hats, with pompous gestures. In the Middle Ages the serfs humbly doffed their bonnets, whilst the noblemen gave the German salute. It was in the Ratskeller at Bremen, about the year 1921, that I first saw this style of salute. It must be regarded as a survival of an ancient custom, which originally signified: “See, I have no weapon in my hand!”

Adolf Hitler, from Hitler’s Table Talk 1941-1944: His Private Conversations

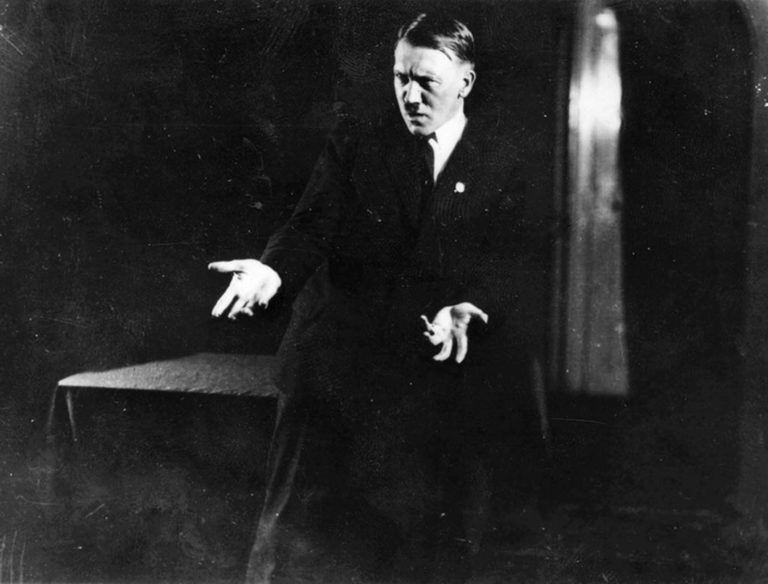

In the early 1920s, as Mussolini and his Blackshirts were cementing their power in Italy, another far-right movement was gathering steam in the beer halls of Munich.

The nascent Nazi Party, led by Adolf Hitler, looked to Italian Fascism with a mixture of admiration and rivalry. Hitler was particularly impressed by Mussolini’s mastery of political symbolism and mass spectacle. He saw how the so-called Roman salute had given the Italian Fascists a powerful, unifying gesture, and he wanted one for his own movement.

The Nazis began using the straight-armed salute, which they called the Hitlergruß (Hitler Greeting) or the Deutscher Gruß (German Greeting), as early as 1921.

By 1926, it was made compulsory for all party members.

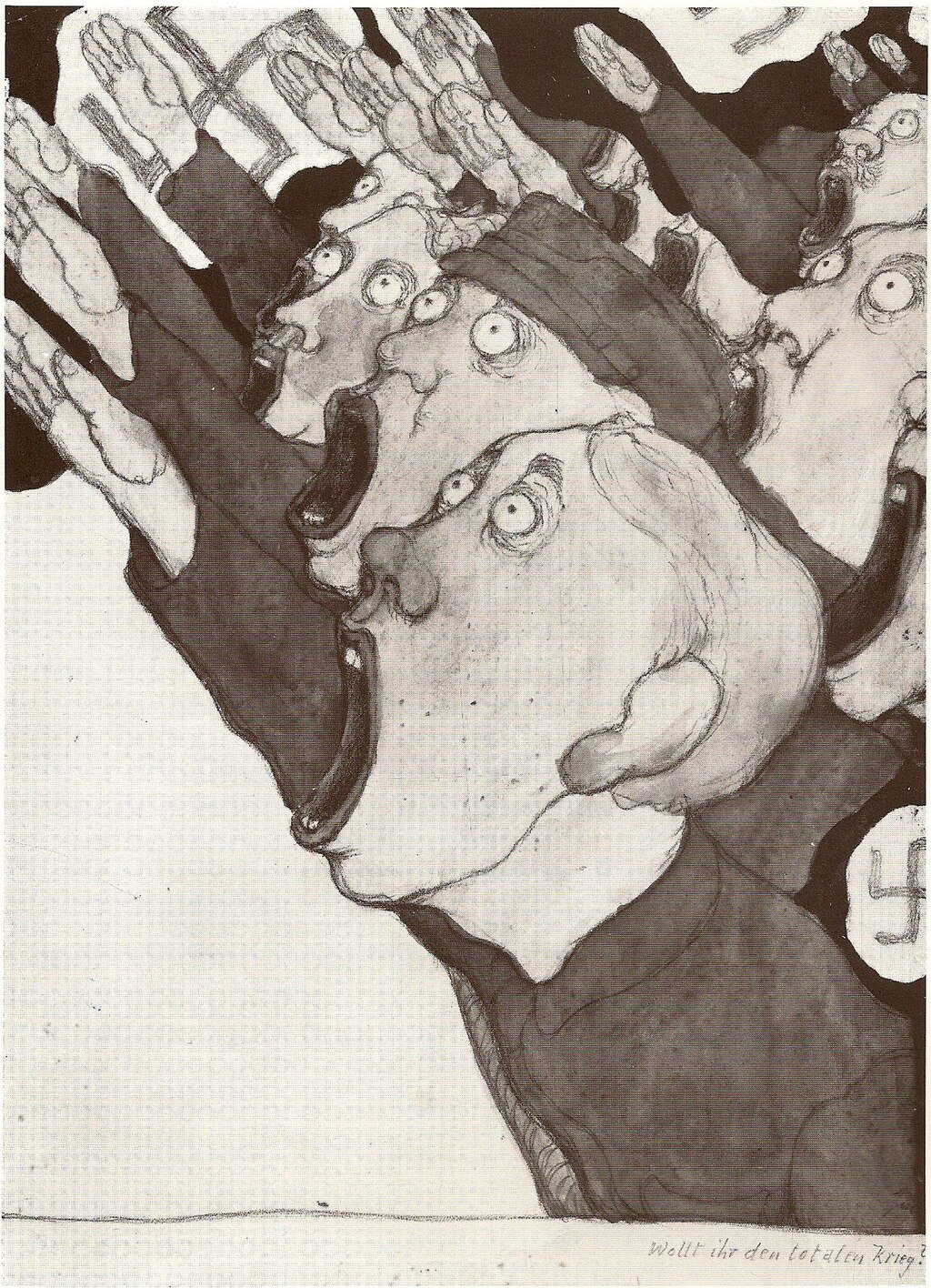

The gesture, performed by extending the right arm rigidly forward with the palm down, was typically accompanied by the cry of “Heil Hitler!” (“Hail Hitler!”) or, in mass rallies, “Sieg Heil!” (“Hail Victory!”).

Like the Italian Fascists, the Nazis claimed an ancient pedigree for their salute. Hitler himself, in his table talk, spun a fanciful tale about Martin Luther being greeted with a ‘German salute’ at the Diet of Worms in 1521.

This was a complete fabrication, a transparent attempt to create a Germanic, rather than Latin, origin for the gesture and to distance it from its Italian fascist contemporary.

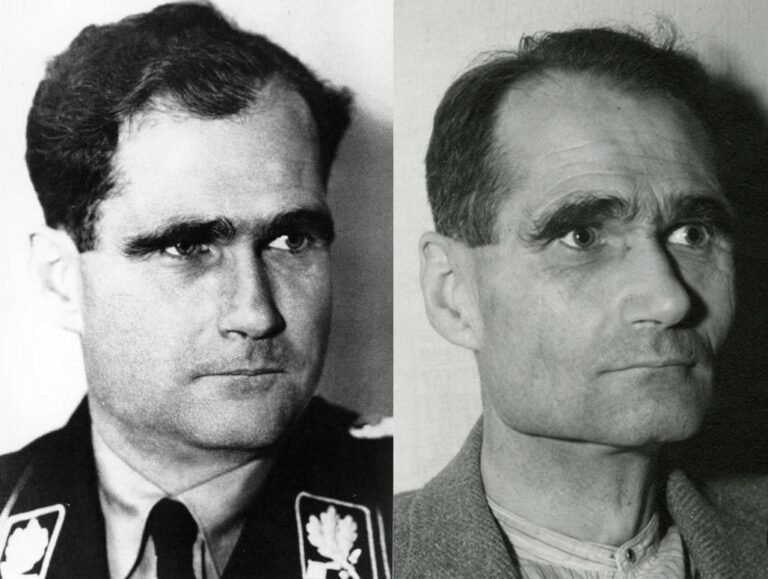

Nazi propagandists, like Rudolf Hess, also published articles claiming the salute had been a spontaneous German gesture since the movement’s earliest days, conveniently ignoring its direct lineage from Mussolini’s Italy and beyond.

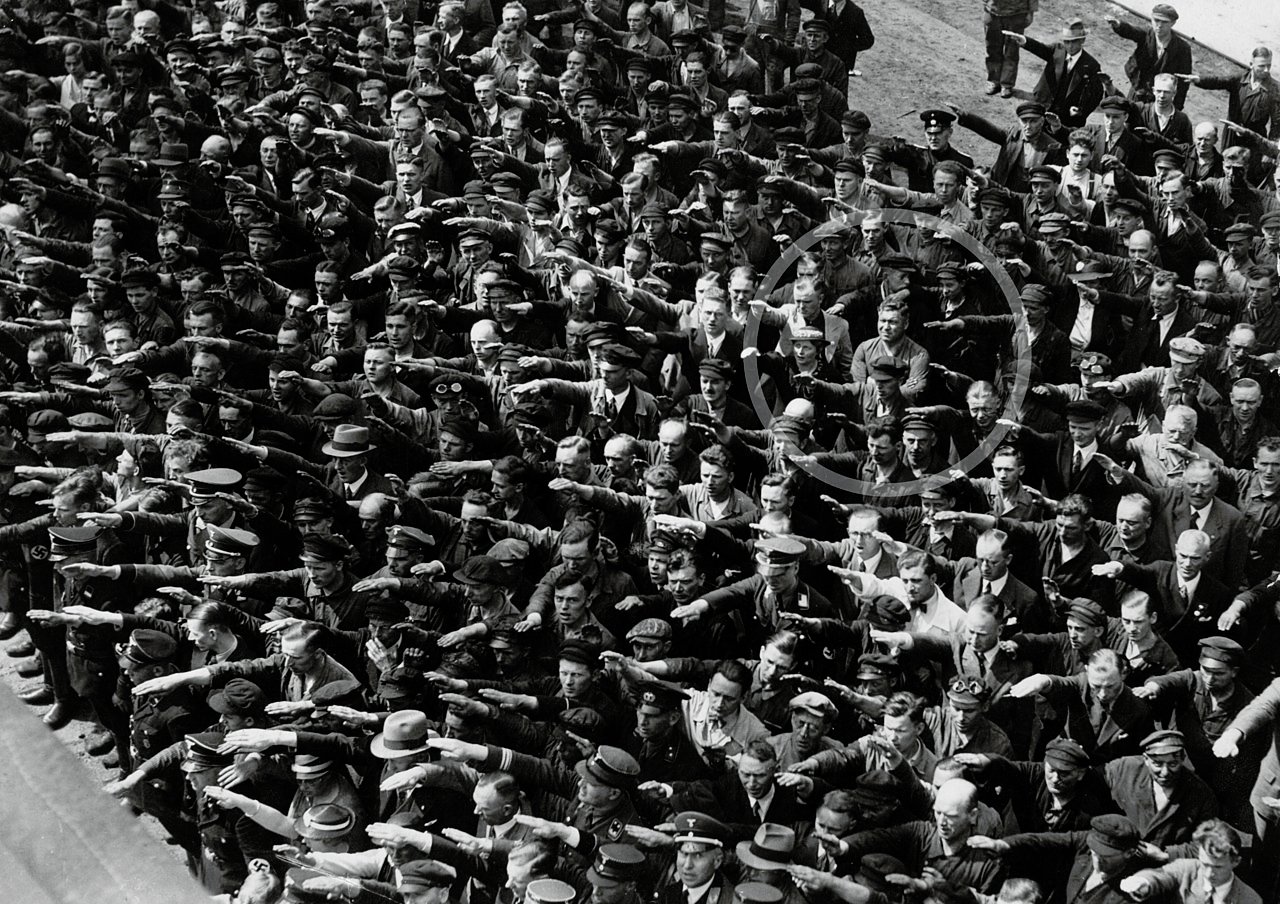

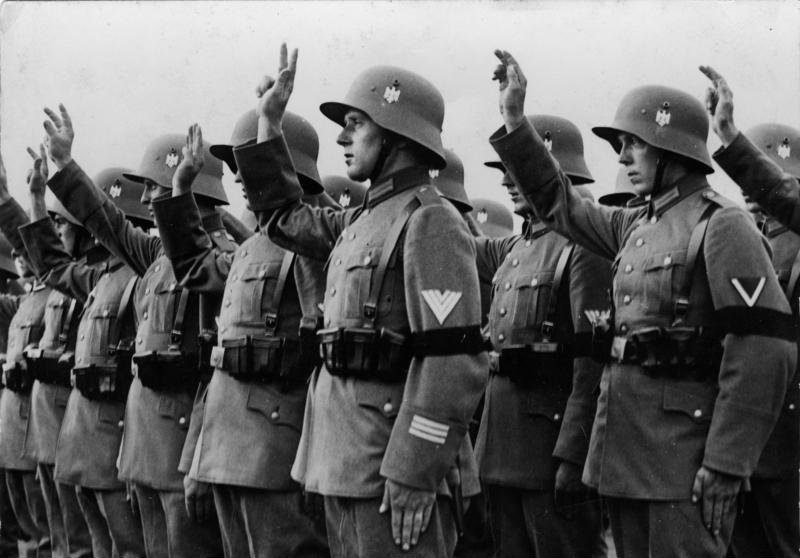

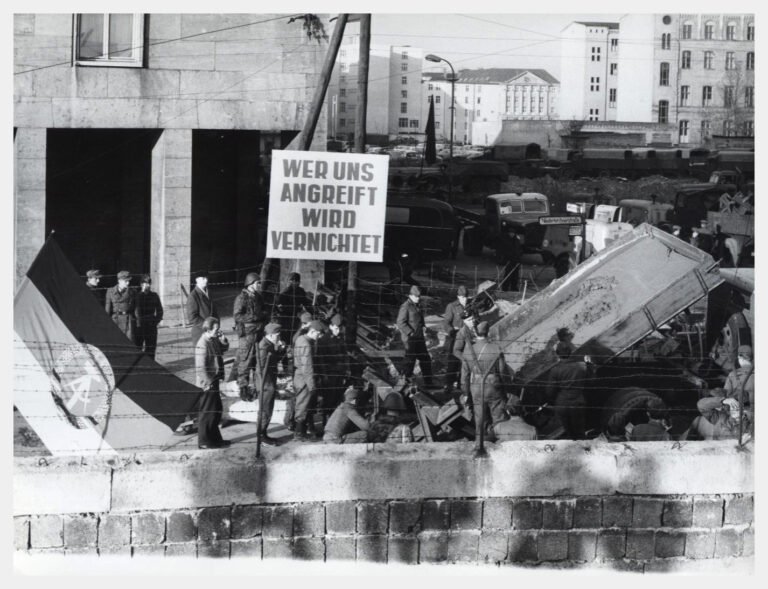

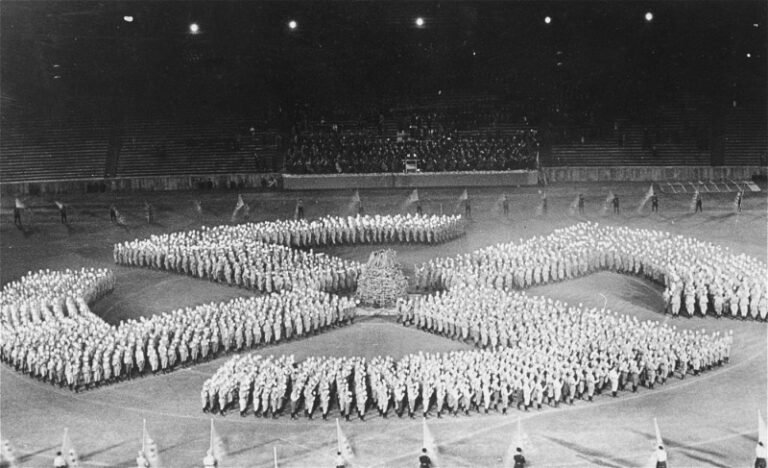

When the Nazis seized power in January 1933, the salute was rapidly transformed from a party ritual into a national duty.

It became the ubiquitous, all-encompassing symbol of the new regime, a daily referendum on one’s loyalty to the Führer. A decree issued on July 13th 1933, by the Minister of the Interior, Wilhelm Frick, made the salute mandatory for all public employees. Soon, it was compulsory in schools, on the streets, and at the start of any public event.

Signs appeared in public spaces reminding citizens of their duty: “Der Deutsche grüßt: Heil Hitler!” (“The German Greets: Heil Hitler!”).

The salute was more than just a greeting; it was a potent psychological tool.

In a totalitarian state that seeks to control every facet of life, a compelled public gesture is a powerful mechanism for enforcing conformity. It turns every social interaction, no matter how mundane, into a political act, a performance of allegiance. To give the salute was to signal your inclusion in the Volksgemeinschaft, the racially pure national community.

To refuse it was a public act of defiance, a dangerous declaration of otherness.

The consequences for not performing the salute could be severe. It was a form of non-conformity that the regime could not tolerate.

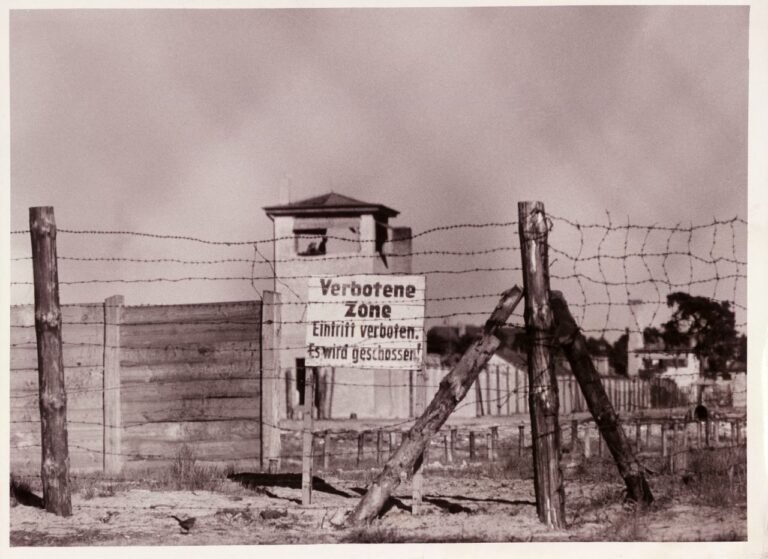

By 1934, special courts were established to punish offenders, with penalties ranging from public humiliation and fines to imprisonment in the newly established concentration camps.

The story of August Landmesser (or Gustav Wegert) provides a chilling illustration of the risks.

A worker at the Blohm+Voss shipyard in Hamburg, Landmesser was famously captured in a 1936 photograph with his arms crossed, defiantly refusing to salute as the crowd around him hailed the launch of a new naval vessel. Landmesser had been a Nazi Party member but was expelled after he became engaged to Irma Eckler, a Jewish woman.

His refusal to salute was an act of personal conscience born of his love for a woman the state had deemed racially inferior. His defiance did not go unpunished. He was arrested multiple times for “dishonoring the race,” imprisoned, and eventually drafted into a penal battalion where he was killed in action.

Irma Eckler was arrested by the Gestapo and murdered, likely at the Bernburg Euthanasia Centre.

Even the German military, the Wehrmacht, was initially reluctant to adopt what it saw as a party political gesture, preferring to maintain its traditional military salutes. For years, a tense compromise existed.

However, after the failed attempt to assassinate Hitler on July 20, 1944, the Führer’s patience ran out. In a move to enforce absolute loyalty, the Hitlergruß was made mandatory for all ranks of the armed forces, replacing the centuries-old military tradition. The party’s symbol had finally and completely consumed the state.

The salute had never truly been a sign of victory; it was a demand for submission

–

Other Instances Of Fakelore

“What seems to be an individual and arbitrary act—a gesture, a posture—is in fact a social and historical product.”

Marcel Mauss, author of ‘Techniques of the Body’

In the grand tapestry of history, threads of origin can become tangled, leading to compelling but ultimately unfounded theories. One such theory suggests a more archaic and artistic origin for the infamous salute: the theaters of Elizabethan England.

The idea posits that in the dimly lit playhouses of Shakespeare’s London, where actors performed epic tales of Roman valor, a need arose for grand, easily visible gestures to convey the classical setting to the groundlings in the cheap seats. The fist-to-the-chest, a more historically plausible Roman gesture of loyalty, was perhaps too subtle. And so, the theory goes, the extended arm was born of theatrical necessity, a piece of stagecraft designed to evoke a sense of Roman grandeur for a popular audience.

A fascinating and romantic notion, it suggests a long, slow corruption of a gesture from artistic expression to political terror. However, it is a myth.

There is no evidence in the scripts of Shakespeare or his contemporaries, nor in the theatrical treatises of the period, to suggest the use of a straight-armed, Roman-style salute. The study of gesture in Elizabethan theater is a rich field, revealing a complex vocabulary of non-verbal communication.

Actors used specific hand movements to convey everything from insults to social status. In Romeo and Juliet, a character bites his thumb to provoke a rival, a gesture Shakespeare has to explain to his audience as a “disgrace to them, if they bear it.” In Julius Caesar, Brutus kisses Caesar’s hand in a feigned act of loyalty just moments before assassinating him. These were gestures rooted in the social codes and conflicts of the Renaissance, not in imagined reconstructions of ancient Rome.

The true artistic wellspring of the salute lies not in the 16th-century Globe Theatre, but, as we have seen, in the 18th-century Parisian studio of Jacques-Louis David.

His neoclassical masterpiece, The Oath of the Horatii, was the true inventor of the gesture. It was an artist’s imagined vision of Roman stoicism, not a historical reenactment.

This invented Roman gesture then found its perfect stage, not in Elizabethan England, but in the spectacular historical dramas of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

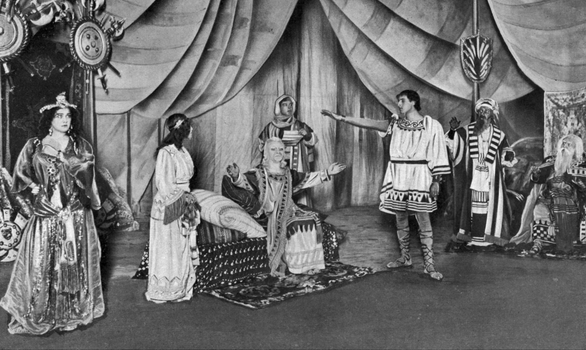

The most influential of these was the American stage production of Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ.

Opening on Broadway in 1899, this adaptation of Lew Wallace’s novel was a theatrical sensation, renowned for its incredible special effects, including a naval battle and a chariot race featuring real horses on massive treadmills.

In keeping with the exaggerated, melodramatic acting style of the era, the play’s producers added the straight-armed salute to various scenes to heighten the Roman atmosphere.

Photographs from the original production show characters greeting each other with the gesture that David had painted over a century earlier. This theatrical choice, made for dramatic effect on a New York stage, did more to cement the ‘Roman salute’ in the public consciousness than any historical text.

It was this tradition of stage and, later, cinematic “fakelore”—as seen in American films like the 1907 version of Ben-Hur and Italian epics like Cabiria—that was seized upon by D’Annunzio, Mussolini, and ultimately Hitler.

They were not reviving a Roman or Elizabethan tradition, but borrowing a piece of modern theater, mistaking artistic invention for historical truth.

–

The Present Day Power of the Salute

“The constantly reiterated declaration of loyalty at once controlled public transactions and fractured personal relationships. And always, the greeting sacralised Hitler, investing him and his regime with a divine aura.”

Tilman Allert, author of ‘The Hitler Salute: On the Meaning of a Gesture’

In the aftermath of the Second World War and the collapse of the Third Reich, Germany faced the monumental task of rebuilding not just its cities, but its very soul.

A crucial part of this process was a legal and cultural reckoning with the symbols that had defined the Nazi regime. The swastika, the SS runes, and, of course, the Hitler salute were not merely historical artifacts; they were seen as carriers of a toxic ideology. To allow their continued use would be to risk the poison seeping back into the body politic.

Consequently, the present-day public display of the Nazi salute is illegal in Germany, a crime punishable by a fine or imprisonment for up to three years. This ban is enshrined in Section 86a of the German Criminal Code (Strafgesetzbuch), which outlaws the “use of symbols of unconstitutional organizations.”

The law is intentionally broad. It does not provide an exhaustive list of banned symbols but instead prohibits “flags, insignia, uniforms, slogans and forms of greeting” associated with groups deemed hostile to the constitution. This explicitly includes the Nazi Party and its various offshoots, as well as other extremist groups. The law also covers symbols that are “so similar as to be mistaken for” the originals, a provision designed to prevent neo-Nazi groups from circumventing the ban with slightly modified versions of forbidden imagery.

However, the ban is not absolute. Recognizing the importance of historical and artistic engagement with the past, the law includes a crucial “social adequacy clause” (Sozialadäquanzklausel).

This provides an exception for the use of banned symbols in the context of “art or science, research or teaching,” and for reporting on current or historical events. This is why a historian can publish a book with a swastika on the cover, a museum can display Nazi uniforms, and a filmmaker can depict characters giving the salute in a historical drama.

For many years, video games were a gray area, but in 2018, this exception was officially extended to them as well, recognizing them as a cultural medium on par with film.

The power of this single gesture remains undeniable.

The banning of the Hitler salute in modern Germany stands as a stark and necessary paradox.

A democratic state must restrict the very freedom of expression it is sworn to protect, precisely to prevent the return of an ideology that would extinguish that freedom entirely.

–

Conclusion

“The brothers stretch out their arms in a salute that has since become associated with tyranny. The ‘Hail Caesar’ of antiquity (although at the time of the Horatii a Caesar had yet to be born) was transformed into the ‘Heil Hitler’ of the modern period.”

American art historian, Albert Boime, analysing The Oath of the Horatii

So, where did the world’s most hated gesture truly come from? Its story is not a straight line to a single, sinister source, but a twisted path of artistic license, cinematic fiction, and political opportunism.

Benito Mussolini, in his quest for imperial branding, did not resurrect a forgotten Roman tradition; he plagiarised a poet. His Roman Salute was a direct lift from the theatrical stylings of Gabriele D’Annunzio, who had helped popularize the gesture not through historical research, but through his work on the 1914 silent film epic, Cabiria.

The salute was born not in the Forum, but on a film set.

It was this potent piece of celluloid fiction—less antiquity and more melodrama—that Adolf Hitler would perhaps unknowingly copy, perfect, and weaponise.

The Nazis transformed a cinematic flourish into a terrifying instrument of social control, a daily referendum on loyalty that held the power of life and death.

But the thread of this saga pulls us deeper still. For the dictators, the poets, and the filmmakers were all unwitting disciples of a single artist, all bowing to the ghost of an 18th-century canvas.

The wellspring of this gesture can be found in one masterpiece: Jacques-Louis David’s 1784 painting, The Oath of the Horatii. An artist’s powerful vision of civic virtue, of liberty and sacrifice for the republic, which served as his personal leitmotif subsequently hijacked by history. Twisted through a century of theatre and terror until it became the universal emblem of absolute submission.

Rather than art imitating life, it appears in this instance that it may have been more a matter of life imitating art.

***

If you’ve enjoyed reading this article, consider booking one of our private guided tours of Berlin.

Sources

Allert, Tilman (2008), The Hitler Salute: On the Meaning of a Gesture, translated by Jefferson Chase, Metropolitan Books, ISBN unavailable.

Arendt, Hannah (1951), The Origins of Totalitarianism, Harcourt, Brace & Company, ISBN 978-0-15-670153-2.

Carrier, David (1988), “Gavin Hamilton’s ‘Oath of Brutus’ and David’s ‘Oath of the Horatii’: The Revisionist Interpretation of Neo-Classical Art,” The Monist, 71(2): 197–213.

Ellis, Richard J. (2005), To the Flag: The Unlikely History of the Pledge of Allegiance, University Press of Kansas, ISBN unavailable.

Evans, Richard J. (2005), The Third Reich in Power: How the Nazis Won Over the Hearts and Minds of a Nation, Penguin Books, ISBN 978-0-14-303790-3.

Ferasin, Francesco (2020), The Fiume Enterprise and D’Annunzio’s Nationalism, publisher and ISBN unavailable.

Hayes, Peter (2017), Why? Explaining the Holocaust, W.W. Norton & Company, ISBN 978-0-393-35357-7.

Johnson, Dorothy (1989), “Corporality and Communication: The Gestural Revolution of Diderot, David, and The Oath of the Horatii,” The Art Bulletin, 71(1): 92–113.

Kershaw, Ian (2015), The Nazi Dictatorship: Problems and Perspectives of Interpretation, Bloomsbury Revelations, ISBN 978-1-4725-8810-4.

Kinnard, Roy; Crnkovich, Tony (2017), Italian Sword and Sandal Films, 1908–1990, McFarland, ISBN 978-1476662916.

Klein, Scott W.; Moses, Michael Valdez (eds.) (2021), A Modernist Cinema: Film Art from 1914 to 1941, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0190949586.

Klemperer, Victor (2006), The Language of the Third Reich: LTI – Lingua Tertii Imperii, Bloomsbury Revelations, ISBN 978-1-4725-8605-6.

Mosse, George L. (1999), The Fascist Revolution: Toward a General Theory of Fascism, Howard Fertig, ISBN 978-0919694114.

Rabinbach, Anson; Gilman, Sander L. (eds.) (2013), The Third Reich Sourcebook, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-22064-4.

Trevor-Roper, Hugh; Hitler, Adolf (2000), Hitler’s Table Talk 1941–1944: His Private Conversations, translated by Norman Cameron and R.H. Stevens, Enima Books, ISBN unavailable.

Winkler, Martin M. (2009), The Roman Salute: Cinema, History, Ideology, Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 978-0801892631.

HISTORICAL ARTICLES

Mythbusting Berlin

Are There Any Nazi Statues Left In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

Visitors to Berlin often arrive expecting to find the physical remnants of the tyranny of the 20th century still standing – statues of dictators, triumphal arches, or bronze idols. Instead, they often find none. The stone symbols and statues of the Third Reich are still gazing down on them, however, hiding in plain sight. But why are there no statues of Hitler? Did the Allies destroy them all in 1945, or is the truth stranger

Could The Western Allies Have Captured Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

To contemplate a Western Allied capture of Berlin in 1945 is to challenge the established endgame of the Second World War. What was the true military and logistical feasibility of a Western Allied assault on the Nazi capital? What factors truly sealed Berlin’s fate, and what might have changed had the Allies pushed eastward?

Answering these questions means delving into the complex interplay of logistics, political maneuvering, and the competing visions for a post-war world

Did Any Of The Rothschild Dynasty Die In The Holocaust? – Mythbusting Berlin

The Rothschild name is synonymous with immense wealth, influence, and persistent conspiracy theories—especially during the era of Nazi Germany. Often targeted by antisemitic propaganda, the family’s survival during World War II has sparked myths about their supposed immunity from Nazi persecution. But did any Rothschild family member actually perish in the Holocaust? This article explores that compelling question, unraveling historical misconceptions and revealing the reality behind one of Europe’s most famous dynasties.

Did Frederick The Great Introduce The Potato To Germany? – Mythbusting Berlin

One of the more bizarre claims to fame attributed to the first King of Prussia is that the man who would go down in history known as Frederick the Great introduced the potato to Germany during his reign back in the 1700s. This starchy root vegetable has undoubtedly become a staple part of German cuisine – an essential addition to any plate of Schnitzel, Schweinshaxn, and Königsberger Klopse – however, whether Frederick the Great is

Did Hitler Escape To Argentina In 1945? – Mythbusting Berlin

Although Nazi leader, Adolf Hitler, certainly remains an inescapable figure, could there be any truth to the story of his escape to Argentina in 1945? That the most wanted man on earth could simply vanish, to spend the rest of his life peacefully in South American obscurity captivates imaginations. Yet, despite numerous investigations, this tale persists primarily as myth—fueled by speculation, hearsay, and conspiracy theories.

Did Hugo Boss Design The Nazi Uniforms? – Mythbusting Berlin

The idea that Hugo Boss – the man whose name now adorns expensive suits and fragrances – was the creative genius behind the Nazi uniforms suggests a terrifying collision of haute couture and holocaust – a marriage of high style and high crimes. The image is striking: a German tailor sketching the ultimate villain’s costume. But history, as usual, is far messier, more bureaucratic, and more banal than the internet memes suggest. To understand who

Did Rudolf Hess Really Commit Suicide? – Mythbusting Berlin

On a summer’s day in 1987, the last Nazi war criminal of the Nuremberg trials was found dead in a prison built for hundreds, yet for two decades, housed only him. The official verdict was suicide, a straightforward end to a life defined by fanaticism, delusion, and contradiction.

But the simplicity of the report belied the complexity of the man and the 46 years he had spent in Allied custody. In the meticulously controlled

Did The Nazis Develop Nuclear Weapons? – Mythbusting Berlin

The Nazi obsession with super-weapons became so serious in the closing stages of the Second World that Adolf Hitler personally believed that such ‘Wunderwaffen’ both existed in a usable form – and would save the country from defeat. Had the Nazis managed to develop nuclear weapons by 1945 – the outcome of the war would surely have been different. But how close were Hitler, Himmler, and his henchmen to developing an A-bomb?

Did The Nazis Invent Decaf Coffee? – Mythbusting Berlin

Persistent rumors claim that Nazis preferred their coffee anything but pure, leading some to wonder if they might have influenced the development of decaffeinated coffee. Although decaf was already widely available across Europe by the mid-20th century, speculation continues: could the Nazis really have played a role in popularizing—or even discovering—this caffeine-free alternative, or is this simply another caffeinated conspiracy cooked up to sensationalize an ordinary historical detail?

Did The Nazis Invent The Bicycle Reflector? – Mythbusting Berlin

The fruits of wartime ingenuity are plenty – so many, in-fact, that it has become somewhat of a worn cliche that as the guns start firing the innovators get to work, often solving problems while providing more problems for the enemy to overcome.The kind of progress that results in the production of newer improved, more lethal weapons, such as to increase the chances of victory.

Did The Nazis Run The Largest Counterfeiting Operation In History? – Mythbusting Berlin

During the Second World War the Nazis masterminded an astonishing plot to destabilise Britain by flooding its economy with counterfeit banknotes. Crafted in secret by concentration camp prisoners, this forged fortune became the most ambitious counterfeiting operation ever attempted. But was it history’s largest? Dive into the extraordinary tale of Operation Bernhard,

rife with deception, survival, and intrigue—revealing the truth behind one of the Third Reich’s most audacious schemes and its surprising legacy.

Did The Second World War End In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

When is a war ever truly over? When the last shot is fired in anger would seem like the best measure. Rarely, though, is it possible to gain insight into such a moment.

Remarkably, a record still exists of such a moment at the end of the First World War on the Western Front. A seismic register and recording of the last belching battery of British guns firing artillery across no-man’s-land, followed by a profound

Did The Spanish Flu Pandemic Help The Nazis Take Power? – Mythbusting Berlin

The devastating Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918-1919 struck amid Germany’s post-war turmoil, compounding social instability, economic hardship, and widespread political disillusionment. Could this catastrophic health crisis have indirectly paved the way for Nazi ascension? While often overshadowed by war and revolution, the pandemic’s profound psychological and societal impacts arguably contributed to the perfect storm, enabling extremist ideologies—including Nazism—to gain popularity and ultimately seize power in a fractured Germany.

Have Adolf Hitler’s Remains Been DNA Tested? – Mythbusting Berlin

In the smouldering ruins of Berlin in 1945, the world’s most wanted man vanished. Did Adolf Hitler, as official history attests, die by his own hand in the Führerbunker? Or did he escape, fuelling a thousand conspiracy theories that have echoed for decades? For years, the Soviets claimed to hold the gruesome proof of his death: a skull fragment and a set of teeth, locked away in Moscow archives. But in an age of definitive

How Did The Nazi Concentration Camps Differ From The Soviet GULAG?

The Nazi concentration camps and Soviet Gulag system have often been conflated in popular imagination—twin symbols of twentieth-century totalitarian horror. Yet the two systems operated on fundamentally different principles. One extracted labor to fuel industrialisation while accepting mass death as collateral damage; the other evolved into purpose-built machinery of genocide. Understanding these distinctions isn’t merely academic—it reveals how different ideologies produce different atrocities, and why Germany and Russia reckon with these legacies so differently today.

How Long Did It Take To Build The Berlin Wall? – Mythbusting Berlin

It is one of the most enduring images of the 20th century: a city divided overnight. The popular narrative tells us that Berliners went to sleep in a unified city and woke up in a prison. While the shock of August 13th 1961, was very real, the idea that the ‘Wall’ appeared instantly is a historical illusion. The physical scar that bisected Berlin was not a static creation, but a living, malevolent beast that evolved

How Many Assassination Attempts On Adolf Hitler Were There? – Mythbusting Berlin

Nazi leader, Adolf Hitler, projected an aura of invincibility, a man of destiny shielded by providence. But behind the carefully constructed image of the untouchable Führer lies a story of constant threat, of bombs that failed to detonate, and errant bullets that missed their mark. Unearth the hidden history of the numerous attempts on Hitler’s life as we explore the courage of those who tried to change the course of history and the devil’s luck

How Many Jews Died In The Holocaust? – Mythbusting Berlin

The answer to the question posed of how many Jews died in the Holocaust is a simple one: too many. That merely one death was an unforgivable obscenity is a fundamental and necessary realisation in understanding the capriciousness of this unparalleled racial genocide. To comprehend, however, the full number of Jews murdered in Europe by the Nazi regime in the 1930s and 1940s is a detective story of epic proportions: the evidence overwhelming, multifaceted, and

How Many People Died Trying To Escape East Germany? – Mythbusting Berlin

The image of the Berlin Wall is seared into our collective memory, a concrete symbol of Cold War oppression. We think of the daring escapes and the tragic deaths of those who failed. But that well-known number is only a fraction of the truth. The story of those who died trying to escape East Germany is far broader and more complex than most imagine, stretching along a thousand-kilometer border and out into the cold waters

How Old Is Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

A relatively new arrival in Europe, Berlin is over 1000 years younger than London, nevermind Rome or Athens, Jerusalem or Jericho. Just how old is Berlin though?

A question fraught with false assumptions and distortions – that has more often than not been answered with propaganda as it has with the cold hard truth.

Was Adolf Hitler A Drug Addict? – Mythbusting Berlin

Solving the enigma of the ‘Führer’ has become a preoccupation for many, since the arrival of the Austrian-German onto the world stage – although moving beyond the mythology without falling into the trap of prejudically extrapolating on the psychopathography of Hitler or demonising so as to excuse his actions has proven problematic. What to make of the man who became more than the sum of his masks? The painter; the military dilettante, the mass murderer,

Was Adolf Hitler A Freemason? – Mythbusting Berlin

History abhors a vacuum, but adores a mystery. Such is the speculative fiction suggesting a secret allegiance behind the rise of the Third Reich – that the catastrophe of the Second World War was orchestrated from the shadows of a Masonic lodge. The image of Adolf Hitler—the drifter from Vienna turned dictator—as a covert initiate of the very brotherhood he publicly reviled, however, creates a paradox that collapses under scrutiny. As when we unlock the

Was Adolf Hitler Gay? – Mythbusting Berlin

In the shadowy corridors of Third Reich history, few questions provoke as much tabloid curiosity and scholarly exasperation as the sexuality of Adolf Hitler. For decades, rumors have swirled—whispered by political enemies in 1930s Munich, psychoanalyzed by American spies in the 1940s, and sensationalized by revisionist authors today. Was the dictator who condemned thousands of men to concentration camps for “deviant” behavior hiding a secret of his own? By peeling back the layers of propaganda,

Was Adolf Hitler Jewish? – Mythbusting Berlin

Was the dictator who orchestrated the murder of millions of European Jews secretly one of them? It is perhaps the darkest irony imaginable, a story whispered for decades in backrooms, bars, and conspiracy forums alike. The most-common rumour – the ‘Frankenberger Myth’ – suggests that Adolf Hitler’s paternal grandfather was Jewish, a secret so damaging it could have unraveled the entire Nazi regime. But where does this claim come from? And, more importantly, is there

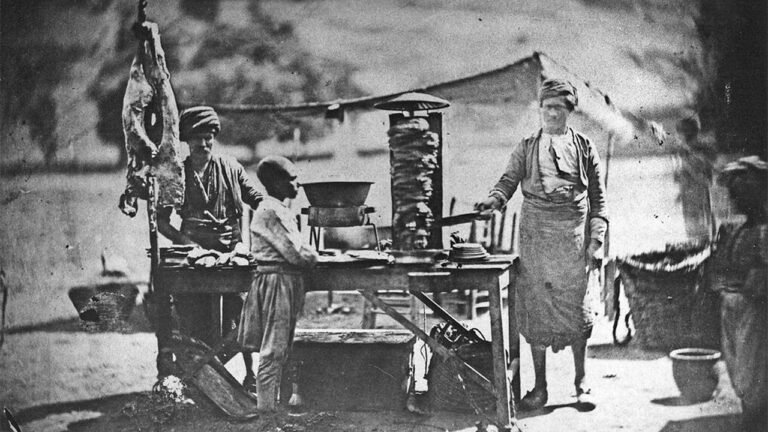

Was Currywurst Invented In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

Explore the story behind what many consider Berlin’s most iconic snack—the ever-so-humble Currywurst. Often hailed as an enduring symbol of culinary creativity amid Cold War scarcity, this humble dish has inspired fierce debate about its true origin. But was it genuinely invented here in Berlin, or have proud locals simply adopted and elevated this spicy street-food favorite into legendary status all their own?

Was Fanta Invented By The Nazis? – Mythbusting Berlin

As one of the most secretive organisations in the world, the Coca Cola corporation refuses to share its secret recipe with anyone. Famously insisting only on shipping the base syrup of its drinks to plants around the world to be carbonated and distributed.

This combined with the trade limitations of the Second World War may have led to the introduction of one of the most popular soft-drinks in the world. But could it be true:

Was Frederick The Great Gay? – Mythbusting Berlin

Frederick II of Prussia, better known as Frederick the Great, is often remembered as the archetypal enlightened monarch – a brilliant military commander, patron of the arts, and learned philosopher. Yet behind the stern portraits of this 18th-century warrior-king lies a personal life long shrouded in intrigue and speculation. Intrigue around the king’s sexual orientation has persisted through the centuries, chiefly revolving around one question: Was Frederick the Great gay?

Was Henry Ford A Nazi? – Mythbusting Berlin

US auto tycoon, Henry Ford, holds the ignominious distinction of being the only American Adolf Hitler praised by name in his National Socialist manifesto: ‘Mein Kampf’. This was not, as it turns out, the only connection between Ford and the Party of Hitler, Himmler, and the Holocaust.

Ford’s overt affinity with the Third Reich reveals a troubling past. How deep these connections ran, and how consequential they were for both sides, is a chapter

Was The Colour Blue Invented In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

Tracing the true history of blue—from ancient Egyptian dyes to the accidental discovery of Prussian Blue in a Berlin lab. We’ll debunk myths about seeing blue, explore colonial indigo plantations, scale mountains with a cyanometer, and trace Van Gogh’s starry skies—all to answer one question: how did Berlin shape our understanding of the world’s rarest color?

Was The Döner Kebab Invented In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

Unlikely icon of immigrant success; fast food symbol of the working class; over-hyped midnight disco eat; or culturally appropriated cuisine? Its influence goes far beyond layers of seasoned meat and fresh vegetables stuffed into pita bread. But does Berlin deserve credit as the Döner Kebab’s true birthplace, or has the city merely refined and popularized a culinary tradition imported from elsewhere?

Was The Fall Of The Berlin Wall An Accident? – Mythbusting Berlin

On a seasonally crisp night in November 1989, one of the most astonishing events of the 20th century occurred. After twenty eight years, three months, and twenty eight days of defining and dividing the German capital, the Berlin Wall ceased to exist – at least in an abstract sense. Although the removal of this symbol of the failure of the East German system would take some time, its purpose – as a border fortification erected

Was The Nazi Party Democratically Elected? – Mythbusting Berlin

The myth persists that Adolf Hitler rose to power through popular democratic choice. Yet history reveals a darker, more complicated truth. Hitler’s ascent involved exploiting democratic institutions, orchestrating violence, propaganda, and political intrigue—not a simple election victory. Understanding how Germany’s democracy collapsed into dictatorship helps illuminate the dangerous interplay between public desperation, elite miscalculations, and extremist ambition, providing crucial lessons for safeguarding democracy today.

Were The Allied Bombings Of Germany War Crimes? – Mythbusting Berlin

The history of the Allied bombing of Germany during the Second World War still triggers fierce debate. Was reducing cities to rubble a necessary evil – justice from above in a just war – or an unforgivable crime? Can the intentional targeting of civilians ever be justified as militarily necessary?

In a conflict where all rules seemed to vanish, an even more pertinent question persists: by the very standards they would use to judge their

Were The Nazi Medical Experiments Useful? – Mythbusting Berlin

Before the Nazi period, German medicine was considered the envy of the world – a shining monument to progress. But deep within that monument, a rot was spreading, one which would collapse the entire structure into an abattoir. From the wreckage, we are left with a profoundly uncomfortable inheritance: a moral enigma wrapped in doctor’s whites.

What to make of the data, the images, and the terrible knowledge gleaned from unimaginable human suffering. Whether

What Are The Origins Of The Nazi Salute? – Mythbusting Berlin

A specter is haunting the modern mind, a gesture so charged with the dark electricity of history that its mere depiction can unleash a storm of controversy.

It is a simple movement: the right arm, stiff and straight, raised to the sky. But in that simplicity lies a terrifying power, a symbol of a regime that plunged the world into an abyss and a chilling reminder of humanity’s capacity for organised hatred.

This

What Are The Origins Of The Nazi Swastika? – Mythbusting Berlin

Long before the legions of the Third Reich marched beneath its stark, unnerving geometry, the swastika lived a thousand different lives. It was a symbol of breathtaking antiquity, a globetrotting emblem of hope and good fortune that found a home in the most disparate of cultures. To even begin to understand its dark 20th-century incarnation, one must first journey back, not centuries, but millennia.

What Are The Pink Pipes In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

A first-time visitor to Berlin could be forgiven for thinking the city is in the midst of a bizarre art installation. Bright pink pipes, thick as an elephant’s leg, climb out of the ground, snake over pavements, arch across roads, and disappear back into the earth. Are they part of a complex gas network? A postmodern artistic statement? A whimsical navigation system? These theories, all logical, are all wrong. The truth is far more elemental,

What Do The Colours Of The German Flag Symbolise? – Mythbusting Berlin

What does a flag mean? Is it merely a coloured cloth, or does it hold the hopes, struggles, and identity of a nation? The German flag, with its bold stripes of black, red, and gold, is instantly recognisable. But the story of its colours is a tumultuous journey through revolution, suppression, and reinvention. The common explanation for their symbolism is a simple, romantic verse, yet the truth is a far more complex and contested tale,

What Happened To Adolf Hitler’s Alligator? – Mythbusting Berlin

It is often said that you can tell a lot about a person by their relationship with animals; that owners often come to look and behave like their pets. Or is it perhaps more that people choose their pets to correspond to their personality? Nazi leader Adolf Hitler’s love of dogs, for example, is well documented but what is there to make of his relationship with reptiles?

What Happenened To The German Royal Family? – Mythbusting Berlin

When the smoke cleared over the trenches in November 1918, the German Empire had evaporated, and with it, the divine right of the Hohenzollern dynasty. Conventional wisdom suggests the family simply vanished into the sepia-toned obscurity of history books—exiled, forgotten, and irrelevant. But dynasties, like weeds in a landscaped garden, are notoriously difficult to uproot entirely. The story of the German royals did not end with the Kaiser’s flight to Holland; it merely shifted gears.

What Is The Difference Between Fascism & Nazism? – Mythbusting Berlin

While the terms ‘Fascist’ and ‘Nazi’ are often bandied around interchangeably as shorthand for tyranny – Italian fascism and German National Socialism were distinctly different beasts. Albeit ideological kin. One an ideology of state-worship, born from post-war chaos and national pride; the other built upon a fanatical, pseudo-scientific obsession with race. Two peas in the same totalitarian pod – twins in tyranny – more succinctly summarised as the Nazi chicken to the Fascist egg.

What Was Checkpoint Charlie? – Mythbusting Berlin

Checkpoint Charlie remains among Berlin’s most visited historical sites, famed worldwide for its significance during the Cold War. Originally established as a modest border-crossing point, it evolved dramatically over the decades into an international symbol of freedom, espionage, and intrigue. Today, critics and locals often dismiss it as little more than a tourist trap—Berlin’s Disneyland—but how exactly did Checkpoint Charlie get its peculiar name, and what truths hide behind its popularity?

What Was Prussia? – Mythbusting Berlin

Prussia’s legacy is both remarkable and contentious—once a minor duchy, it rose dramatically to shape modern European history. Renowned for military discipline, administrative efficiency, and cultural sophistication, Prussia was instrumental in uniting the German states, laying foundations for a unified Germany. But how did this kingdom, with its roots in Baltic territories, achieve such prominence, and why does its complex history continue to evoke admiration, debate, and occasional discomfort in Germany today?

What Was The Berlin Airlift? – Mythbusting Berlin

In the ruins of 1948, the silence of Berlin was not a sign of peace, but a held breath before a new catastrophe. The city, drowning in rubble and political intrigue, became the staging ground for the twentieth century’s most audacious gamble. While popular history remembers the chocolate parachutes and smiling pilots, the reality of the Berlin Airlift was a terrifying operational nightmare born from a ruthless currency war. It wasn’t just a humanitarian mission;

What Was The Socialist Kiss? – Mythbusting Berlin

It is one of the most curious and enduring images of the Cold War: two middle-aged, grey-suited men, locked in a fervent embrace, their lips pressed together in a kiss of apparent revolutionary passion. This was the ‘Socialist Fraternal Kiss’, a ritual that, for a time, seemed to encapsulate the unwavering solidarity of the Eastern Bloc.

But what was behind this seemingly intimate gesture? Was it a genuine expression of camaraderie, a piece of

Who Built The Berlin Wall? – Mythbusting Berlin

One of the most common questions I have encountered from people curious about Berlin, and often so cryptically phrased. Who built the Berlin Wall? A simple five-word query, yet one that can be read one of two ways. More than thirty years since the ‘Fall of the Wall’, the story of its construction continues to baffle many who are mainly familiar with its existence through knowledge of its importance…

Who Really Raised The Soviet Flag On The Reichstag? – Mythbusting Berlin

One iconic photograph has come to symbolise the Red Army’s victory over Nazi Germany in 1945—the Soviet flag waving triumphantly above Berlin’s battered Reichstag building. Yet behind this enduring image lies controversy, confusion, and political manipulation. Who truly raised the Soviet banner atop the Reichstag? Was it a spontaneous act of heroism or carefully staged Soviet propaganda? Decades later, unraveling the truth reveals surprising layers beneath the mythologized symbol of Soviet triumph.

Who Was Really Responsible For The Reichstag Fire? – Mythbusting Berlin

Various theories have been posited as to who actually set fire to the German parliament in 1933. Was it the opening act in an attempted Communist coup or a calculated false flag operation carried out by elements of the Nazi Party, intended to create the conditions necessary for introducing single-party rule? And what part did the young man from Holland, arrested shirtless inside the building the night of the fire, play in this event?

Who Were The Last Nazis On Trial? – Mythbusting Berlin

More than eighty years after the Holocaust, courtrooms across Germany still echo with testimony from the final chapter of Nazi justice. Centenarian defendants in wheelchairs, their faces hidden behind folders, arrive to answer for crimes committed in their youth. These are not the architects of genocide—those men faced their reckoning at Nuremberg decades ago. These are the guards, the secretaries, the bookkeepers: ordinary people who enabled extraordinary evil. Their trials represent a legal revolution: the

Why Is Berlin The Capital Of Germany? – Mythbusting Berlin

There was little in its humble origins—as a twin trading outpost on a minor European river—to suggest that Berlin was destined for greatness. It sits on the flat expanse of the North European Plain, a landscape once dismissively referred to as the “sandbox of the Holy Roman Empire.” Unlike other world capitals, it lacks breathtaking scenery or a naturally defensible position. It is a city built not on majestic hills or a grand harbour, but