“At seven o’clock [on 11 June 1940] we entered into conference. … I urged the French Government to defend Paris. I emphasised the enormous absorbing power of the house-to-house defence of a great city upon an invading army. I recalled to Marshal Pétain the nights we had spent together in his train at Beauvais after the British Fifth Army disaster in 1918, and how he, as I put it, not mentioning Marshal Foch, had restored the situation. I also reminded him how Clemenceau had said: “I will fight in front of Paris, in Paris, and behind Paris.” The Marshal replied very quietly and with dignity that in those days he had a mass of manoeuvre of upwards of sixty divisions; now there was none. He mentioned that there were then sixty British divisions in the line. Making Paris into a ruin would not affect the final event.”

Winston Churchill, The Second World War, Volume Two: Their Finest Hour (1949)

In the spring of 1944, amid the clink of champagne glasses in the Nazi-occupied Paris and the rustle of haute couture, a French baroness made what seemed like a small, if bold, decision: she moved her seat to avoid sitting next to the wife of a high-ranking Nazi ambassador.

It was a subtle act of defiance, borne of quiet disgust.

Yet it set in motion a tragic chain of events.

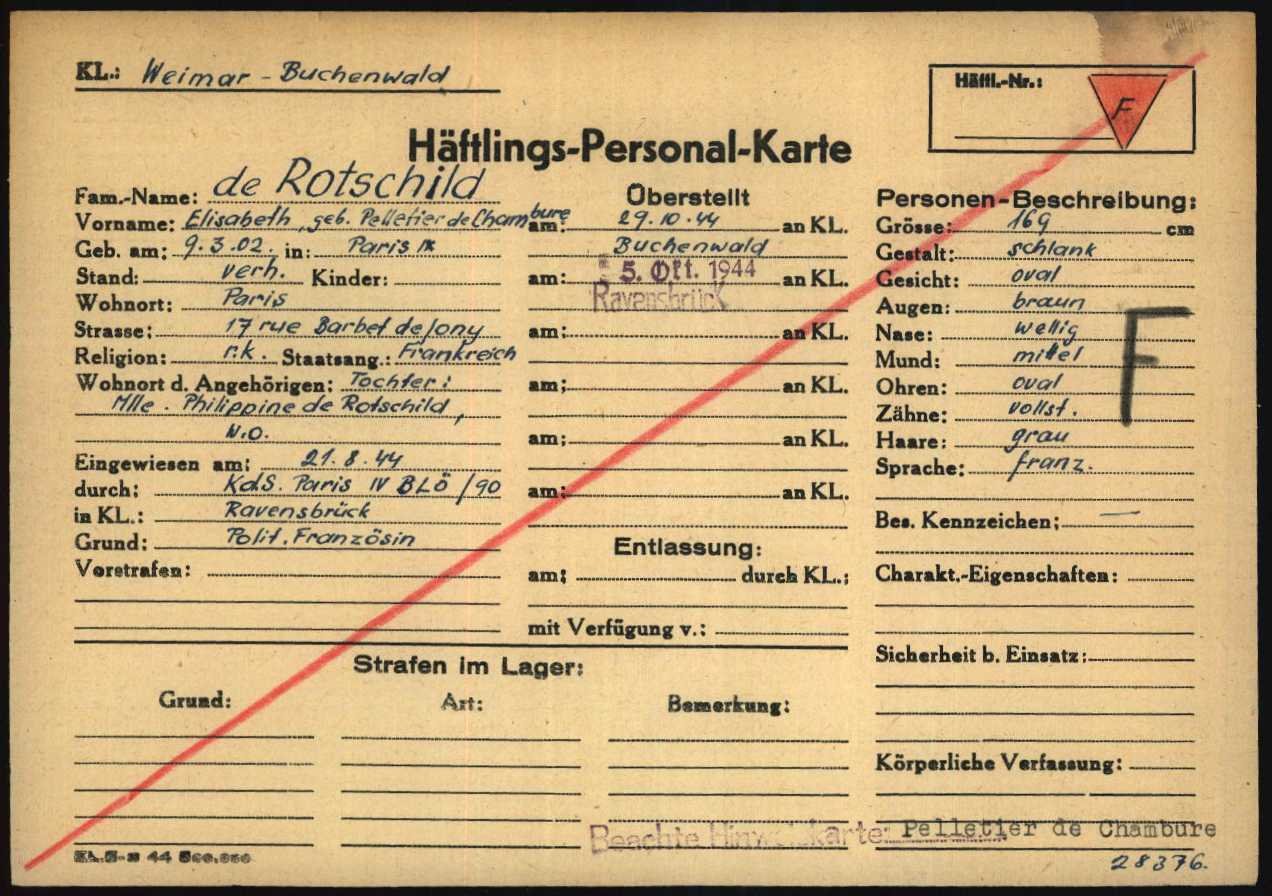

That woman – Elisabeth Pelletier de Chambure – would soon find herself arrested by the Gestapo and eventually perish behind the barbed wire of Ravensbrück, a notorious Nazi concentration camp north of Berlin.

In doing so, it has been said that she earned the grim distinction of being the only member of the illustrious Rothschild family to die in the Holocaust.

The Rothschild name has long been synonymous with immense wealth and influence. Spread across Europe, this prominent Jewish family weathered many storms over the centuries. But the Second World War and the Holocaust posed an existential threat inescapable even to the Rothschilds. Many of them fled or found ways to survive Nazi persecution.

The fate of Elisabeth de Rothschild stands out as a dramatic and poignant exception, a story of tragedy that also cuts through the myths surrounding wartime elites.

It is a window into the capricious cruelty of the Nazi regime and a reminder that wealth and status offered no absolute protection from tyranny.

–

The Rothschilds

“The distinctiveness of the Rothschilds, apart from their extreme wealth and multinational base, was that they literally married their cousins.”

Brenda Maddox, All in the Rothschild Family, Washington Post, April 29, 2003

The Rothschild family rose to prominence as one of Europe’s wealthiest and most influential Jewish dynasties.

Originating in the Jewish ghetto of Frankfurt in the 18th century, Mayer Amschel Rothschild’s five sons established banking houses in Frankfurt, London, Paris, Vienna, and Naples – an international empire of finance.

By the early 20th century, the Rothschilds stood at the pinnacle of high society in multiple countries, wielding significant economic power and indulging in the trappings of aristocracy. They were patrons of art and science, owners of grand estates and vineyards, and in some cases ennobled by the states they served.

Yet their very name also attracted envy, suspicion, and antisemitic conspiracy theories long before the Nazis came to power.

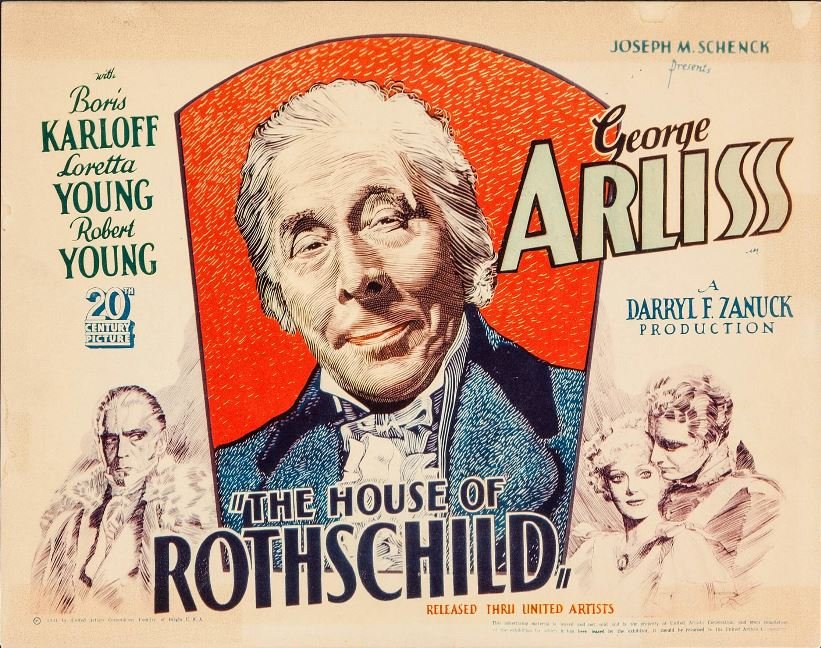

When Adolf Hitler’s Nazi regime took hold in Germany in 1933, its virulent antisemitism and propaganda often singled out the Rothschilds as epitomes of the so-called “Jewish plutocracy” that the Nazis demonized. Nazi ideologues painted the family as sinister puppet-masters of international finance.

In truth, by the 1930s many Rothschilds were assimilated, cosmopolitan figures – some even converted to Christianity or married outside the faith. But none of that mattered to Nazi racial doctrine.

In Nazi eyes, a Rothschild was first and foremost a Jew, and thus a target.

As the clouds of war gathered over Europe, various branches of the Rothschild family found themselves in peril.

In Austria, Baron Louis de Rothschild experienced the danger directly when Germany annexed Austria in March 1938 (the Anschluss). Baron Louis, one of the leading bankers in Vienna, was arrested by the Gestapo and held hostage at the Hotel Metropole in Vienna – the same building that became Gestapo headquarters.

The Nazis made clear that his freedom would come at a price. In what came to be known as the “Rothschild ransom,” his family was forced to pay an enormous sum (rumored at $10 million) and sign over valuable assets to secure his release.

After more than a year in custody, Baron Louis was allowed to leave Austria in May 1939, a shattered man whose personal fortune had been largely extorted. He was luckier than Austria’s former Chancellor, Kurt von Schuschnigg, who remained a prisoner in the next room – but this episode starkly demonstrated that not even the Rothschilds’ wealth could guarantee safety under Nazi rule.

In France and other countries that would soon be occupied by Germany, the Rothschilds braced for a similar onslaught. France’s branch of the family, centered on Baron Philippe de Rothschild and his relatives, had deep roots in the country’s economy (they owned the famous Château Mouton Rothschild winery and were partners in the de Rothschild Frères bank). They also had deep patriotic ties to France.

When the Second World War erupted in 1939, several French Rothschilds served in uniform. Baron Élie de Rothschild and his brother Alain, for example, joined a cavalry regiment and went to the front when Germany invaded France in 1940. Others in the family prepared to flee or go into hiding as the German advance threatened Paris. The fall of France in June 1940 saw the Nazi victors quickly move to seize Jewish property – and few prizes were bigger than the Rothschilds’ collections of art, wineries, and mansions.

Within days of occupying Paris, Nazi officials (including Hermann Göring and art-looting units like the Einsatzstab Rosenberg) targeted Rothschild assets. Baron Philippe de Rothschild’s bank vaults were plundered of their treasures; indeed, a famous photograph later captured American soldiers recovering a looted Rothschild painting from Neuschwanstein Castle in Germany at war’s end.

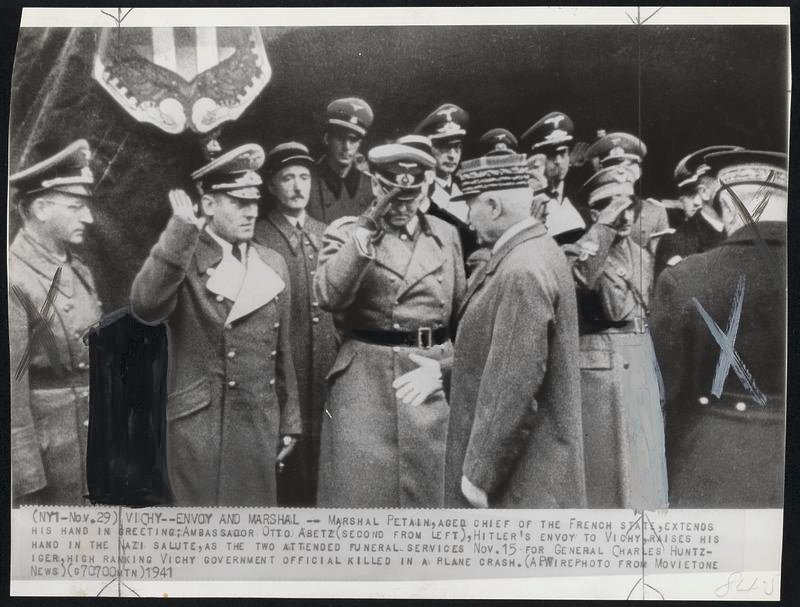

This systematic looting was overseen in part by Otto Abetz, the German ambassador to occupied France, who took a personal interest in confiscating Jewish-owned art (11,000 paintings and thousands of other valuables from families like the Rothschilds, as he later testified).

Yet, even as their possessions were stolen and their businesses aryanised, the Rothschild individuals managed, in large part, to escape the worst fate – deportation to Nazi camps – by going underground or fleeing abroad. Many had the means and connections to get out of Europe or to survive in hiding.

Baron Philippe de Rothschild, for instance, was initially arrested by Vichy French authorities in 1940 and had his beloved vineyard seized. Upon release, he wasted no time in leaving France; by late 1940 or 1941 he was in England, joining General Charles de Gaulle’s Free French Forces and fighting to liberate his homeland.

Philippe’s cousins in the British branch of the family were of course safely across the Channel (some, like Victor Rothschild in Britain, even put their talents to use in the Allied war effort). Other French Rothschilds scattered: some to the unoccupied Vichy zone in the south (at least until it too was taken over in 1942), others eventually to America or neutral countries.

By mid-war, a striking pattern had emerged: despite their prominence as arch-enemies in Nazi propaganda, the Rothschilds had largely evaded the Holocaust’s slaughter. They had suffered financial losses and hardship, but almost all were still alive.

This fact has fueled numerous myths and conspiracy theories – the erroneous idea that the Rothschilds were somehow ‘’in league’ with the Nazis, or that their wealth immunised them completely from Nazi brutality.

The reality was far more complex.

The family’s fame was both a danger and, paradoxically, a shield: the Nazis found the Rothschild name useful for propaganda and extortion, and sometimes preferred to hold certain family members hostage (as with Baron Louis) rather than immediately kill them. Moreover, by virtue of social connections or sheer geographical luck, many Rothschilds got out in time.

But not Elisabeth de Rothschild.

–

Elisabeth Pelletier de Chambure

“…her elegance, the brilliant make-up, gossamer stockings, her poise and the way she wore her jewels. As she moved into a drawing room full of well-dressed people, she could still take my breath away.”

Philippe de Rothschild, Milady vine (1985)

Elisabeth Pelletier de Chambure was born in Paris on March 9th 1902, into an affluent and well-connected French family.

The Pelletier de Chambure family were aristocratic Catholics with roots in the Burgundy region. One of Elisabeth’s ancestors was General Laurent Augustin Pelletier de Chambure, a distinguished officer under Napoleon. Her father, Auguste, held the post of mayor in a Burgundy commune, and her mother, Camille, was likewise of high social standing.

They were, by all accounts, integrated members of the French elite – patriotic, Catholic, and moneyed.

Elisabeth herself was raised in privilege, accustomed to country châteaux and Parisian salons, and educated in the refined manners expected of a young lady of her class. Strikingly beautiful and spirited, she acquired the nickname “Lili” among those close to her.

In 1923, at the age of 21, she entered into her first marriage. Her husband was a Belgian nobleman, Jonkheer Marc Edouard de Becker-Rémy, a man of her own social milieu. The couple had a son, Édouard, born in 1924.

For a time, Elisabeth lived the life of a young aristocratic wife in the Roaring Twenties, likely flitting between Paris and Brussels, attending society functions and enjoying the interwar good life. However, the marriage did not last.

By the early 1930s, cracks had formed in the relationship – perhaps exacerbated by the fact that Elisabeth had met another man who captured her heart: Baron Philippe de Rothschild.

Philippe de Rothschild was a larger-than-life figure. A member of the French branch of the Rothschild family, Philippe was a grandson of Baron James de Rothschild (founder of the French line) and heir to a vast fortune. But Philippe carved his own path as well – he was a wine magnate, running the famed Château Mouton Rothschild vineyard in Pauillac, and something of a playboy and patron of the arts.

Philippe took up Grand Prix motor racing; using the pseudonym “Georges Philippe” in order to race anonymously.

Elisabeth encountered him in social circles (indeed, Philippe was actually a distant cousin by marriage of her first husband).

What began as an affair of the heart soon produced concrete consequences: in 1933, Elisabeth gave birth to a daughter, Philippine. The baby girl’s biological father was Philippe de Rothschild, even though Elisabeth was still legally married to Becker-Rémy at the time.

It was a scandalous situation for the milieu – an aristocratic woman having a child out of wedlock with a famous (and Jewish) lover. Elisabeth’s determination to be with Philippe did not waver. She divorced Becker-Rémy in January 1934, after which she and Philippe de Rothschild were married in Paris the same month.

In marrying Philippe, Elisabeth made a momentous personal choice: she converted from Catholicism to Judaism, the faith of her new husband.

The wedding included a religious ceremony conducted by the Grand Rabbi of Paris, Julien Weill.

It’s worth pausing on this fact.

In the 1930s, conversion from Catholic to Jewish was relatively uncommon – and it carried social risks, even before the Nazi era. For Elisabeth, joining the Rothschild family meant fully embracing their identity.

What she may have seen as a meaningful personal transformation, the Nazis – already in power in Germany at this point – would view as an unforgivable crime.

For a time, the newlyweds lived a life of glamour and privilege. They divided their time between Paris and the picturesque chateau and vineyards of Mouton Rothschild in the Bordeaux region.

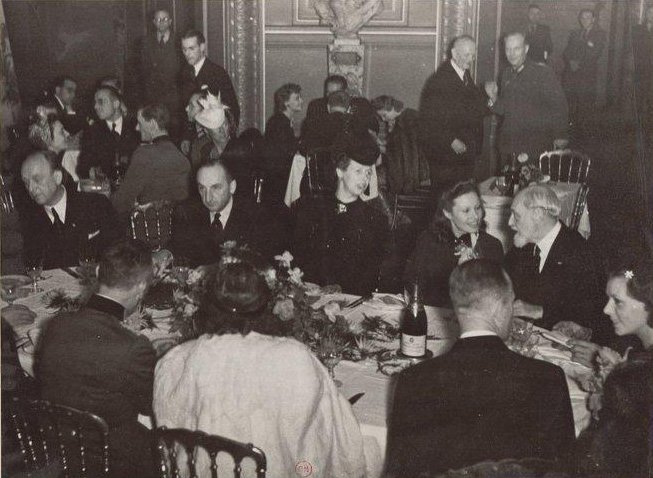

Photographs from the mid-1930s show Baroness Elisabeth de Rothschild – as she was now styled – at elegant parties and cultural events, the very picture of a cosmopolitan French aristocrat (albeit one with a famous Jewish name). In 1938, the couple had a second child together – a son named Charles Henri. Tragically, the boy was born with severe health issues and died in infancy.

The loss put a strain on their marriage. Philippe, known for his restless and flamboyant nature, and Elisabeth, perhaps wounded by grief and juggling her duties to two young children (her daughter Philippine and son Édouard from her first marriage), began to drift apart. By 1939, on the eve of the Second World War, their relationship had soured to the point of separation. It was said to be an acrimonious split.

The loss of this child put an end to what Philippe later described as ‘a partnership of great passion but also enormous tempestuousness and despair.’

Elisabeth ceased using the Rothschild name in daily life and reverted to her maiden name, Pelletier de Chambure.

Little did they know that a far greater storm was about to break – one that would toss their lives into chaos and put them on very different trajectories.

Photographs from the mid-1930s show Baroness Elisabeth de Rothschild – as she was now styled – at elegant parties and cultural events, the very picture of a cosmopolitan French aristocrat (albeit one with a famous Jewish name). In 1938, the couple had a second child together – a son named Charles Henri. Tragically, the boy was born with severe health issues and died in infancy.

The loss put a strain on their marriage. Philippe, known for his restless and flamboyant nature, and Elisabeth, perhaps wounded by grief and juggling her duties to two young children (her daughter Philippine and son Édouard from her first marriage), began to drift apart. By 1939, on the eve of the Second World War, their relationship had soured to the point of separation. It was said to be an acrimonious split.

Philippe later described the marriage as ‘a partnership of great passion but also enormous tempestuousness and despair.’

Elisabeth ceased using the Rothschild name in daily life and reverted to her maiden name, Pelletier de Chambure.

Little did they know that a far greater storm was about to break – one that would toss their lives into chaos and put them on very different trajectories.

When Germany invaded Poland in September 1939 and France declared war, Elisabeth’s estrangement from Philippe became a secondary concern.

Philippe was called up for military service and later became involved in the fight against Germany. Elisabeth, living in Paris with 6-year-old Philippine (and possibly with her older son Édouard, though he may have been with his father or other family), had to navigate the uncertainties of a country at war. The sense of safety she might have felt from her social status was gradually eroding.

As a Rothschild by marriage, she was potentially on the radar of antisemitic forces. As a Catholic by birth, she might have hoped for some measure of protection or at least anonymity.

In May 1940, the German Blitzkrieg smashed through French defenses. By June, Paris was declared an open city and fell to the Germans without a fight. Elisabeth’s world was now under Nazi occupation. Still legally married (though separated) from a prominent Jew and herself a convert to Judaism, she was in a precarious position. The Vichy regime, which governed unoccupied France and collaborated with the Nazis, quickly enacted antisemitic statutes. These laws defined who was considered Jewish, mostly based on ancestry.

Elisabeth, interestingly, might not have been classified as Jewish by Vichy’s racial laws because she had no Jewish parents or grandparents – she was ‘Jewish by marriage and conversion.’

However, such nuances could mean little if the occupying Nazis chose to view her as part of the Rothschild family they detested. Initially, Elisabeth did not flee Paris. Perhaps she could not bear to abandon her home or didn’t anticipate the full danger. Perhaps she was constrained by having young children. Or perhaps, as later accounts suggest, she believed her Catholic background and high social status would shield her from the worst.

This would prove to be a tragic miscalculation.

By the end of 1940, Elisabeth and Philippe both had direct encounters with the new Vichy and Nazi order. Philippe, as noted, was arrested by Vichy authorities along with Elisabeth around the time of the German occupation; their estate, Château Mouton Rothschild, was seized by the state under Aryanisation policies.

Elisabeth and Philippe were soon released from that initial detention (likely due to lack of charges and possibly because of Philippe’s prominence or bribes). Philippe decided that remaining in France was too dangerous and 1941 he had made it to England to join the Free French.

Elisabeth, however, stayed in France with her daughter.

She was now an estranged Rothschild stuck in German-occupied territory, using her maiden name.

One can imagine the uncertainty and fear in her life. Did she consider fleeing south to the unoccupied zone (the Line of Demarcation separated German-occupied northern France from Pétain’s regime in the south until late 1942)? There are indications she did. According to one account, in 1941 Elisabeth attempted to cross that demarcation line with forged papers – an effort to escape or possibly to reunite with friends in Vichy territory – but she was caught by the German authorities. This incident resulted in her being briefly arrested by the Gestapo on charges of using false permits.

Allegedly, Fernand de Brinon, a high official of the collaborationist Vichy regime, secured her release.

Precisely what happened next is a bit murky.

What we do know is that Elisabeth was still in Paris by 1943/44, moving in some social circles – albeit carefully. She appears to have kept a low profile, but she did not entirely withdraw from society.

This brings us to the fateful moment that would later be called “the Abetz Affair.”

–

The Abetz Affair

“Had all of us in France meekly, lawfully carried out the orders of the German master, no Frenchman could have ever looked another man in the face. Such submission would have saved the lives of many, some very dear to me. But, France would have lost its soul.”

Commandant le Baron de Vomécourt, ‘What Americans forget about French resistance’

In occupied Paris, a strange semblance of normal life persisted for those in the upper echelons of society, even as war raged elsewhere.

Theatres, cafes, and fashion houses remained open. The Nazi elite and their French collaborators indulged in the city’s luxuries. High-end couturiers like Coco Chanel, Christian Dior (then a young designer for the house of Lelong), and Elsa Schiaparelli continued to put on fashion shows for a clientele that now included the wives of German officers and Vichy dignitaries.

It was a surreal bubble of glamour amidst oppression – and it was at one of these events that Elisabeth’s fate was sealed.

Otto Friedrich Abetz was Hitler’s ambassador to Vichy France and de facto plenipotentiary in occupied Paris. Fluent in French and married to a French woman, Abetz was a key figure in the Nazi administration in France. He and his wife, Suzanne Abetz, were known to host and attend many social functions, trying to win the hearts and minds (or at least obedience) of the French elite. Suzanne, being French, acted as a bridge between the Germans and Parisian society; she wielded considerable influence and was described as “almost as powerful as her husband” in the Paris social scene.

Both Abetz and his wife were also notoriously antisemitic and wholly loyal to the Nazi cause. Elisabeth de Rothschild, even under her maiden name, could hardly go unnoticed in such circles. She was a striking woman and, though separated from Philippe, still bore the aura of the Rothschild name.

Sometime in the early 1940s – likely 1943 or early 1944 – Elisabeth attended a fashion show at Elsa Schiaparelli’s salon in Paris. Schiaparelli, a leading couturière, counted both French women and German occupiers’ wives among her patrons.

On this day, one of the attendees was Madame Suzanne Abetz, the ambassador’s wife. Whether by coincidence or by the salon’s seating arrangement, Elisabeth found herself assigned a seat adjacent to Mme. Abetz at the runway show. For Elisabeth, whose sympathies clearly did not lie with the occupiers, this was an intolerable situation. In a room no doubt filled with elegant chatter, Elisabeth made a decision. She publicly refused to sit next to Suzanne Abetz. Accounts vary as to how overt the gesture was: some say she discreetly switched her seat at the last minute; others suggest it was obvious to onlookers that the Baroness de Rothschild was snubbing the ambassador’s wife.

Either way, the message was clear: Elisabeth would not play along with the polite fiction of Franco-German camaraderie. She would not share pleasantries or rub shoulders with the spouse of a Nazi official, even if everyone else in the room found it “chic” to do so. This act of defiance, though small in the grand scheme of war, deeply offended the Abetzes. Suzanne Abetz, humiliated by the slight, undoubtedly reported the incident to her husband.

Otto Abetz, who was already no friend to the Rothschilds, must have been enraged.

Here was an aristocratic woman – a Rothschild no less – openly disrespecting the Nazi social order. It could not go unpunished. According to later testimony, the very next day Elisabeth Pelletier de Chambure (Baroness de Rothschild) was arrested by the Gestapo.

The arrest likely took place at Elisabeth’s Paris residence. By this time, Germany’s war fortunes were waning, but Paris was still under tight control, especially in the tense months after the Allied landings in Normandy. When the Gestapo came for Elisabeth, her young daughter Philippine was at home. Philippine, about ten years old then, witnessed the terrifying scene of her mother being taken away by German officers.

In later interviews, Philippine recounted that she herself was nearly caught up in the arrest but was spared because one of the German officers saw the little girl and was reminded of his own daughter.

In a fleeting moment of mercy or sentimentality, the officer decided not to take the child. This small kindness would mean the difference between life and death for Philippine, who went on to survive the war. For Elisabeth, no mercy was shown.

What was the official reason given for Elisabeth’s arrest? The Nazis seldom admitted to jailing someone over a social slight. Instead, they accused Elisabeth of crimes against the regime. One charge, resurrecting the earlier incident, was that she had attempted to flee illegally (the forged travel permit case). Additionally, simply being a Rothschild and the estranged wife of a known “enemy of Germany” (Philippe was by now fighting with de Gaulle) was enough to seal her fate. Unlike some other prominent individuals who were held as bargaining chips, Elisabeth was not as valuable to the Nazis – her husband was out of reach, and she herself, having converted to Judaism, could be categorized as a Jewish prisoner without causing a diplomatic stir.

Whether the Abetz Affair sealed Lili’s fate – or as some accounts would have it, Elisabeth was arrested because she had organised a charity event on behalf of the Jews rounded up in Drancy transit camp, on their way to the deportation – the outcome was clear.

Elisabeth was drawn into the machinery of Nazi repression.

After her arrest in 1944, she was interrogated by the Gestapo in Paris and detained at Fresnes prison until her deportation from Quai aux bestiaux de Pantin (Cattle yard of Gare de Pantin) on August 15th 1944 – on the last convoy of political deportees to leave the Paris region.

At the time, the electricity in Paris had been cut off and the train drivers were on strike as Allied forces fought their way towards the city from the coast of Normandy.

Gare de L’est, the usual deportation point for trains heading eastwards towards Germany, had been destroyed by an Allied bomb so instead this last convoy departed from Gare de Pantin.

Onboard were approximately 2,200 men and women – including 158 allied airmen – Elisabeth Pelletier de Chambure among them.

The next day, the convoy was blocked in Nanteuil-sur-Marne. The railway bridge which spans the Marne having been destroyed by the British Royal Air Force. This last group of deportees from Paris then travelled, supervised by Waffen-SS, on foot several kilometres to reach the Nanteuil – Saâcy station, on the other side of the river.

From there, another train would take them to Germany – and the fate awaiting them in the barbed-wire confines of Buchenwald and Ravensbrück.

–

Ravensbrück & Death

“… nowhere else in the world did reality have as much effective power as in the camp, nowhere else was reality so real. In no other place did the attempt to transcend it prove so hopeless and so shoddy.”

Jean Améry, At the Mind’s Limits: Contemplations by a Survivor on Auschwitz and Its Realities (1966)

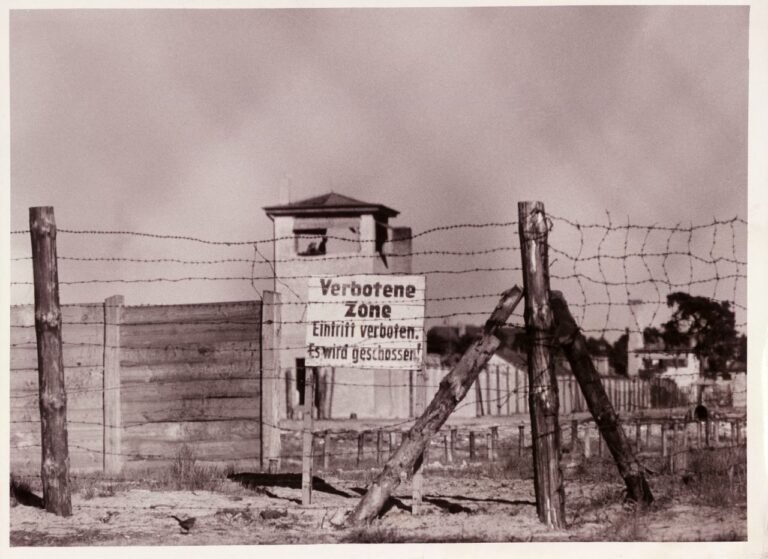

In the small town of Fürstenberg, about 90 kilometers north of Berlin, lay the Ravensbrück concentration camp – the largest camp for women in the Third Reich.

Established in 1939, Ravensbrück was initially intended for female political prisoners and ‘asocial’ women (a Nazi term encompassing everyone from resistance fighters to Jehovah’s Witnesses, to alleged criminals). Over time, its population swelled to include Jews, Gypsies (Roma & Sinti), POWs, and women from over 20 occupied nations.

By 1944, Ravensbrück had become a hellscape of overcrowding, forced labor, medical experimentation, and mass murder.

It was into this living nightmare that Elisabeth de Rothschild was cast.

We do not have a detailed diary of Elisabeth’s experience in Ravensbrück. What we know comes from fragmentary testimonies and what is recorded about her fate in the Nazi records.

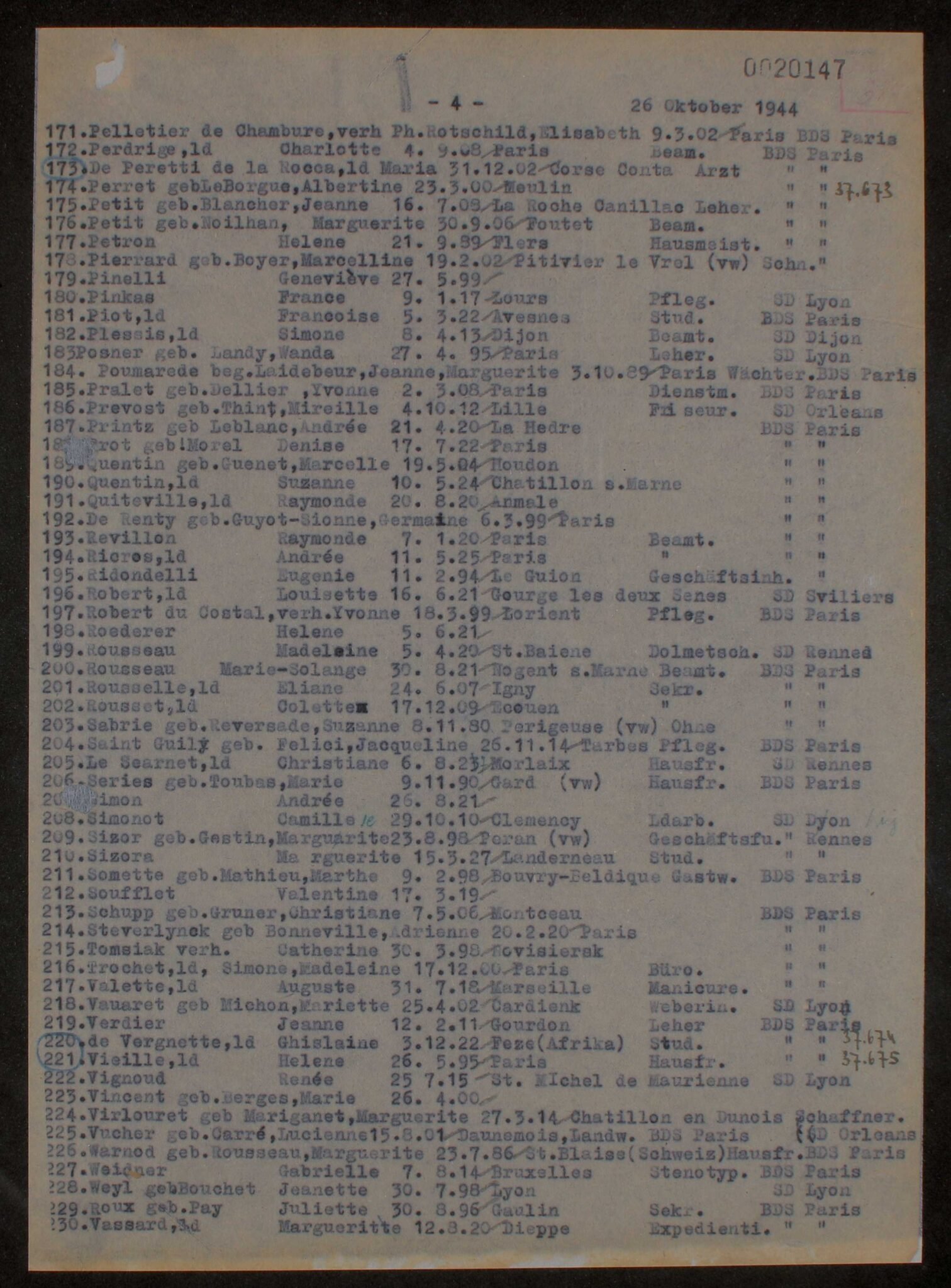

First registered as Buchenwald concentration camp following her deportation from Paris, Elisabeth was given the prisoner number: 28376. Her prisoner card lists her as being born on March 9th 1902, and incorrectly noted as being married as “de Rotschild” (the German translation, ‘Red Shield’, of the Rothschild name). She is listed as being from the IX district of Paris and an F appears on her camp badge (identifying her as French).

The designation featured on her identity card justifying her detention: ”Political Frenchwoman”’.

From Buchenwald, Elisabeth was sent to the Ravensbrück camp and arrived on August 21st 1944.

Being a 42-year-old woman of high society offered no advantages in a Nazi camp. Elisabeth would have had her head shaved and what belongings she still had with her taken.

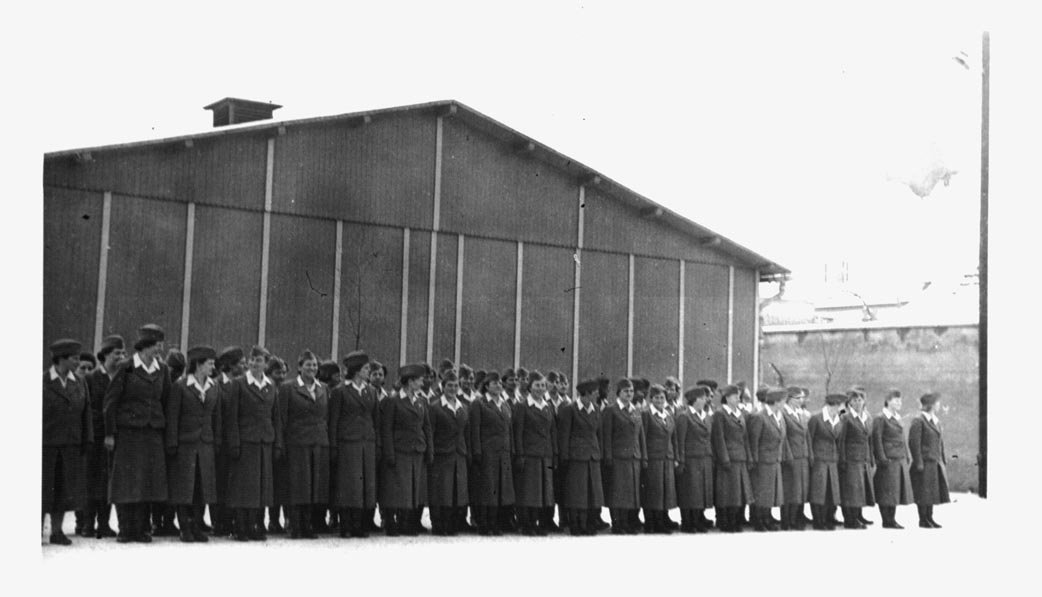

At the time, the camp was severely overcrowded and prisoners were left unprocessed outside the original campgrounds in an open field. Four days later, a large tent would be erected in this field to house the prisoners.

Around 12,000 additional prisoners would arrive at the camp between August and October 1944 – including many women and children from Warsaw, as the Nazi campaign to quash the Polish resistance in the city was underway.

The initial number of occupants of this huge tent were 900 people crammed inside with no access to latrines or lavatories, wooden boxes were put around the perimeter with buckets inside.

The daily regimen at Ravensbrück was brutal. Prisoners woke at dawn for roll call in the Appellplatz, standing outdoors for hours in bitter cold or rain. They were assigned to labor details – some women worked in textile workshops, others in construction, others in sordid tasks like operating the camp crematorium.

By 1944, a large Siemens factory nearby was using prisoners as slave laborers. Food was scarce and starvation rations had grown even worse as the war turned against Germany. Beatings and arbitrary executions by SS guards were common. Disease, especially typhus, was rampant due to the unsanitary conditions and malnutrition.

It is possible that she encountered other Frenchwomen there; indeed, by late 1944 a number of French Resistance women and even some prominent figures (like General de Gaulle’s niece) were imprisoned at Ravensbrück.

Notably, Catherine Dior – the sister of fashion designer Christian Dior – was one such French deportee. Catherine Dior arrived in Ravensbrück in August 1944 as a Resistance member. She survived the camp and later recounted some experiences.

It would appear that Elisabeth was eventually officially processed at Ravensbrück in October – nearly two months after her arrival.

Shortly after this, she was sent to a subcamp of Buchenwald – the Torgau ammunition works.

At Torgau, one of the women – Jeannie Rousseau from Brittany, told the others who had been sent there that they should rebel and refuse to make weapons as they were part of the resistance. Jeannie had worked as an interpreter for German generals in France and even travelled to Peenemünde to see Hitler’s secret weapons. When the guards told them they could instead be sent back to Ravensbrück, the protest caved.

By the winter of 1944/1945, Elisabeth had been sent to another camp, this time one of the 33 locations tied to Ravensbrück – the Königsberg an der Oder airfield.

Most of the women were employed at the airfield to expand the runways (earthworks), under the supervision of German foremen and masters. Others were assigned to the “forest commando” to dig up tree stumps, tamp down snow on the runways (when the snow plow failed), take part in the construction of aircraft hangars and load material at the station stop at the airfield.

When the ground staff left the airfield on January 31st, all the guards of the women’s concentration camp left in a hurry, including the twenty so-called concentration camp guards, the SS guards and the temporary guards from the ranks of the intelligence assistants.

The female prisoners at the airfield then experienced a brief period of liberation from their captors before the facility was reoccupied on February 2nd and 3rd by Waffen-SS units.

Unlike Torgau, which was in the south east of Germany, the Königsberg an der Oder airfield was close to the frontline in Pomerania (now Poland) and Soviet troops were advancing towards the airfield in early 1945.

It is not known how many women were transported back to the main camp in Ravensbrück. It is also unknown whether they had to walk the eighty kilometres or whether they were transported in cattle wagons.

It is likely that Elisabeth was among them.

In early 1945, the camp authorities at Ravensbrück began exterminating prisoners at a higher rate than usual. They sent many on death marches westward to flee the advancing Red Army. They also constructed a gas chamber at Ravensbrück in early 1945 (prior to that, most killings were by shooting, lethal injection, or sending prisoners to other camps like Auschwitz).

Elisabeth did not live to see liberation.

On March 23rd 1945, just weeks before Soviet forces liberated Ravensbrück, Elisabeth died in the camp.

The official, or at least commonly reported, cause was epidemic typhus, the disease that had been ravaging the weakened camp population.

Typhus, spread by lice in the horrible sanitary conditions, killed thousands in the camps during those final months – Anne Frank died of typhus around the same time at Bergen-Belsen. It is entirely plausible that Elisabeth succumbed to this illness, exhausted and immuno-compromised as she must have been.

However, there is a darker version of her end, one that her estranged husband Philippe de Rothschild came to believe. In his memoirs published decades later, Philippe recounted that Elisabeth was thrown alive into a crematorium oven by the Nazis. Philippe was not an eyewitness; he heard this information after the war, likely from camp survivors or other second-hand sources.

Could it be true? Sadly, there were instances of SS guards disposing of living prisoners in such a manner when execution by bullet became inefficient or when they wanted to terrorize others. Yet without documentary proof, we cannot be certain.

Philippe’s account may reflect the anguish of a husband who, having lost the woman who was once his wife and the mother of his child, imagined (or was told) the worst possible scenario of her death.

The exact manner of Elisabeth’s demise thus remains unclear, but the outcome is the same: a life cut short by deliberate human cruelty. She was 43 years old. At war’s end, she left behind her two children: her son Édouard (who fortunately had been out of harm’s way, possibly with his father in Belgium or elsewhere) and her daughter Philippine, who had survived in hiding in France under a false name.

When Ravensbrück was liberated by Soviet troops in late April 1945, they found only a few thousand prisoners left – the rest had been evacuated or killed.

There is no grave for Elisabeth; like so many victims, her remains were likely reduced to ashes in the camp’s crematorium.

Those ashes subsequently scattered by the camp guards into the Schwedtsee lake that borders the Ravensbrück camp.

–

Élie de Rothschild

“We who survived the Camps are not true witnesses. We are those who, through prevarication, skill or luck, never touched bottom. Those who have, and who have seen the face of the Gorgon, did not return, or returned wordless.”

Primo Levi, as quoted by Eric J. Hobsbawm, The Age of Extremes: The Short Twentieth Century, 1914-1991

Elisabeth’s death was a singular tragedy in the Rothschild family, but the Second World War did not leave the other Rothschilds untouched.

It is illuminating to compare her fate with the experiences of another Rothschild who lived through the war: Baron Élie de Rothschild.

Élie’s wartime story is very different – he did not perish, and in fact went on to lead a long and successful life – yet his experiences highlight how even the scions of great families were swept up in the global conflict, each in their own perilous orbit.

Élie de Rothschild was a cousin of Philippe and a member of the French Rothschild banking family (often referred to as the Rothschilds of Paris). Born in 1917, Élie was a generation younger than Elisabeth. When war broke out, he was in his early twenties – a dashing young man of noble heritage, but also a patriotic Frenchman who answered his country’s call to arms. Élie and his brother Alain both served as officers in a French cavalry unit, the 11th Cuirassiers.

In the desperate days of May 1940, as German forces blitzed into France, the Rothschild brothers went to the front “like Pancho Villa, with a horse and a sabre,” Élie later quipped.

This almost romantic image of two Rothschilds riding to battle speaks to the sense of duty and bravery that many in their class felt – an echo of a bygone era of chivalry clashing with the brutal modern warfare of tanks and dive-bombers.

The romance was short-lived.

France’s collapse was swift, and Élie de Rothschild’s unit was overwhelmed. In June 1940, near the Belgian frontier, Élie was captured by the Germans (as was his brother Alain, who was wounded).

Suddenly, the young Baron found himself a prisoner of war.

He was not seized for being a Rothschild or a Jew (though he was certainly both by Nazi reckoning); he was captured as a French officer, which in a way might have afforded him more protection than if the Gestapo had nabbed him as a civilian.

As a POW, Élie fell under the Geneva Conventions. However, one can imagine the Nazis quickly realized who their high-profile captive was. Élie’s captors ultimately sent him to a special POW camp for troublesome or notable officers – the infamous Colditz Castle in Germany.

Colditz was a maximum-security prison for Allied officers who had attempted escapes from other camps. Élie indeed had tried to escape from his first camp near Nienburg, which earned him a transfer to Colditz.

There, behind medieval fortress walls, he spent the remainder of the war. Colditz, while no holiday, was worlds apart from Ravensbrück.

The prisoners at Colditz (who included British lords and other luminaries) were not subjected to torture or slave labor. They were relatively well-fed compared to concentration camp inmates and had access to Red Cross packages. They focused much of their energy on escape attempts and keeping up their morale. Élie even managed an extraordinary personal milestone while imprisoned: he got married by proxy.

In October 1941, inside Colditz, Élie stood in for his own marriage vows (with a photo of his fiancée present) – his bride Liliane, from the prominent Fould-Springer family, took her vows in Cannes, Vichy France, several months later with an empty chair for Élie.

When Germany surrendered in 1945, Élie was liberated from the POW camp and returned to France. He emerged to find that his family’s bank had been shuttered and their mansion occupied, but the family members themselves were alive. Élie’s brother Alain had also survived POW life; their cousin Guy de Rothschild (who had fought as well) survived in hiding and later in North Africa with the Free French; their fathers, such as Baron Robert de Rothschild and Baron Édouard de Rothschild, had endured the occupation years in Switzerland or in concealment. The French Rothschilds, though impoverished compared to their pre-war selves, were intact. In fact, Élie went on to help rebuild the Rothschild businesses in France.

He took charge of the famed Château Lafite Rothschild vineyard after the war and was instrumental in restoring the bank and other enterprises.

He lived until 2007, reaching the age of 90. His war experiences, while challenging, became just one chapter in a rich life. In interviews and memoirs, Élie spoke with a touch of humor about some wartime episodes, but also with solemnity about the losses. What makes Élie’s story relevant to Elisabeth’s is the poignant contrast it provides.

Both Élie and Elisabeth were French Rothschilds caught in the storm of the Second World War.

Both ended up in German custody. But Élie was a male Rothschild fighting as a uniformed soldier; Elisabeth was a female Rothschild targeted as a civilian enemy.

Élie’s captors respected the rules of war (more or less) because Allied POWs had to be treated decently if Germany wanted its own POWs to be treated decently.

Elisabeth’s captors, on the other hand, operated under no constraints when dealing with those deemed racially or politically undesirable. So we see that fate dealt very different hands: Élie languished in a POW camp but survived honorably; Elisabeth languished in a concentration camp and perished ignominiously.

**

Conclusion

“It is thus the blackest of ironies that the only person named Rothschild killed by the Nazis was not a Jew and had disowned the family name.”

Niall Ferguson, author of The House of Rothschild

YES & NO – To the Rothschild family and historians, the divergent wartime stories of Élie and Elisabeth highlight an extraordinary irony: the only member of the Rothschild dynasty to die in the Nazi camps was not one of the family’s many Jewish-born sons who fought or fled, but a woman who had married into the family and had even been born of Catholic lineage.

Despite having taken her maiden name at the time of her deportation, Elisabeth Pelletier de Chambure remained married to Philippe de Rothschild – and thus at the time of her internment and death was still Baroness de Rothschild.

A woman by marriage a Rothschild; by faith a Jew; by birth a French aristocrat – who perished amid the horrors of Ravensbrück in 1945.

In-fact there are more than 500 people with the Rothschild name known to have died in the Holocaust, albeit only one of those came from the top of that illustrious family of finance and wine.

Her deportation, and internment, however, were based on her status as a French political prisoner – as evident in her registration card from Buchenwald.

The camps and subcamps that she was sent to were not part of the Operation Reinhard series of extermination camps but rather concentration camps – where “extermination through labour” was the preference.

Thus to state that Elisabeth de Rothschild died in the Holocaust – the name given to the attemped extermination of all Jews in Europe by the Nazis – would be erroneous.

Elisabeth de Rothschild was not imprisoned as a Jew and did not perish as a Jewish prisoner.

A semantic issue which may seem irrelevant to many – albeit an important one in answering the question: “Did any of the Rothschild dynasty die in the Holocaust?”.

***

If you’ve enjoyed reading this article, consider booking one of our private guided tours of Berlin.

HISTORICAL ARTICLES

Mythbusting Berlin

Are There Any Nazi Statues Left In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

Visitors to Berlin often arrive expecting to find the physical remnants of the tyranny of the 20th century still standing – statues of dictators, triumphal arches, or bronze idols. Instead, they often find none. The stone symbols and statues of the Third Reich are still gazing down on them, however, hiding in plain sight. But why are there no statues of Hitler? Did the Allies destroy them all in 1945, or is the truth stranger

Could The Western Allies Have Captured Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

To contemplate a Western Allied capture of Berlin in 1945 is to challenge the established endgame of the Second World War. What was the true military and logistical feasibility of a Western Allied assault on the Nazi capital? What factors truly sealed Berlin’s fate, and what might have changed had the Allies pushed eastward?

Answering these questions means delving into the complex interplay of logistics, political maneuvering, and the competing visions for a post-war world

Did Any Of The Rothschild Dynasty Die In The Holocaust? – Mythbusting Berlin

The Rothschild name is synonymous with immense wealth, influence, and persistent conspiracy theories—especially during the era of Nazi Germany. Often targeted by antisemitic propaganda, the family’s survival during World War II has sparked myths about their supposed immunity from Nazi persecution. But did any Rothschild family member actually perish in the Holocaust? This article explores that compelling question, unraveling historical misconceptions and revealing the reality behind one of Europe’s most famous dynasties.

Did Frederick The Great Introduce The Potato To Germany? – Mythbusting Berlin

One of the more bizarre claims to fame attributed to the first King of Prussia is that the man who would go down in history known as Frederick the Great introduced the potato to Germany during his reign back in the 1700s. This starchy root vegetable has undoubtedly become a staple part of German cuisine – an essential addition to any plate of Schnitzel, Schweinshaxn, and Königsberger Klopse – however, whether Frederick the Great is

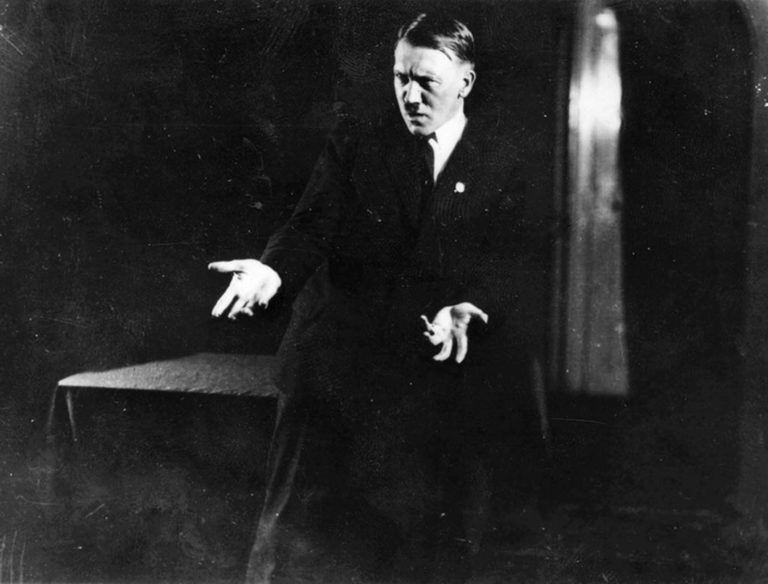

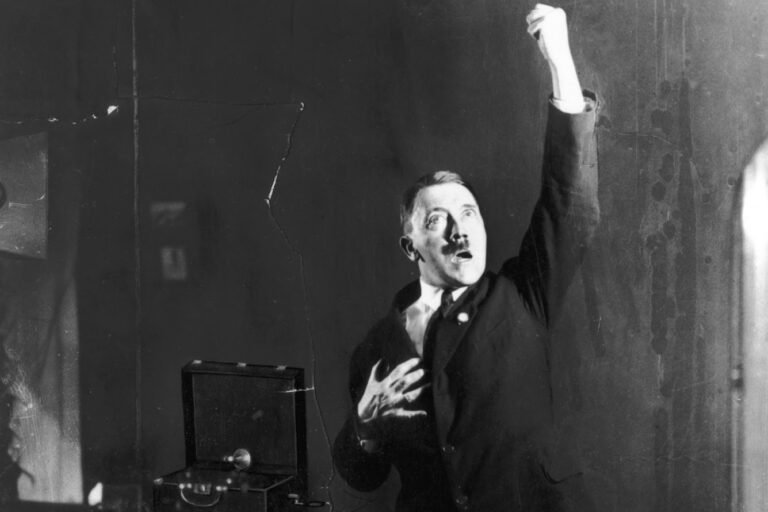

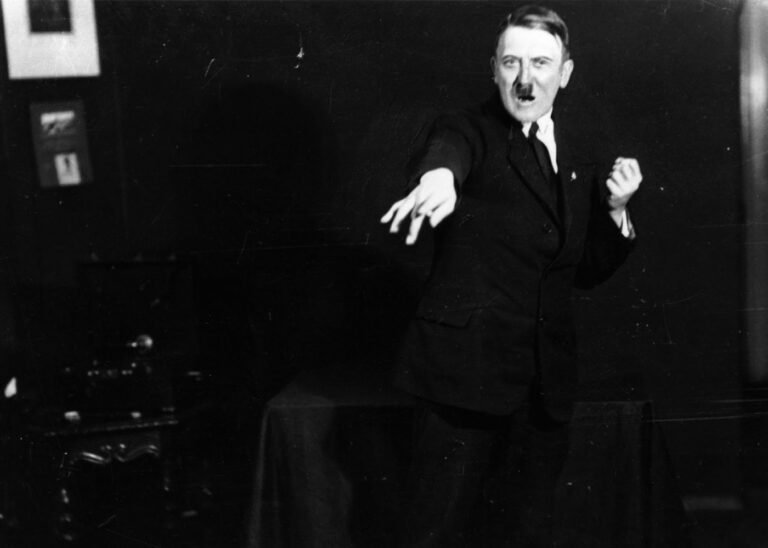

Did Hitler Escape To Argentina In 1945? – Mythbusting Berlin

Although Nazi leader, Adolf Hitler, certainly remains an inescapable figure, could there be any truth to the story of his escape to Argentina in 1945? That the most wanted man on earth could simply vanish, to spend the rest of his life peacefully in South American obscurity captivates imaginations. Yet, despite numerous investigations, this tale persists primarily as myth—fueled by speculation, hearsay, and conspiracy theories.

Did Hugo Boss Design The Nazi Uniforms? – Mythbusting Berlin

The idea that Hugo Boss – the man whose name now adorns expensive suits and fragrances – was the creative genius behind the Nazi uniforms suggests a terrifying collision of haute couture and holocaust – a marriage of high style and high crimes. The image is striking: a German tailor sketching the ultimate villain’s costume. But history, as usual, is far messier, more bureaucratic, and more banal than the internet memes suggest. To understand who

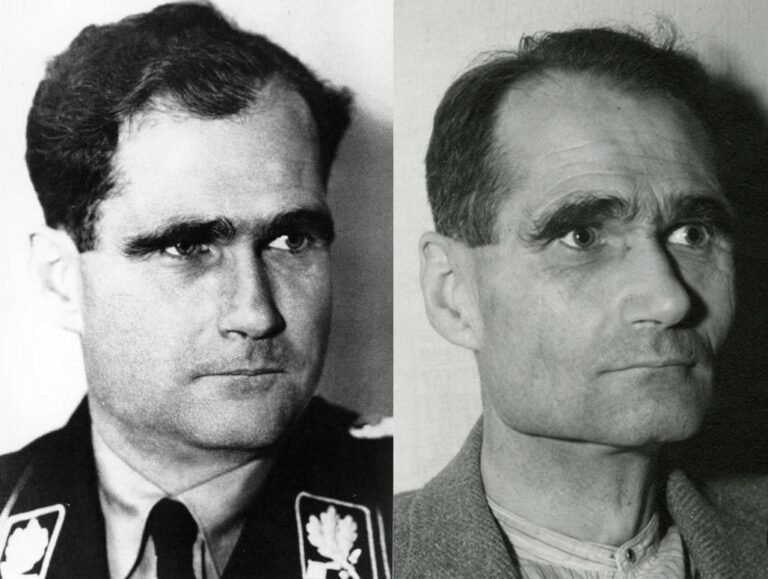

Did Rudolf Hess Really Commit Suicide? – Mythbusting Berlin

On a summer’s day in 1987, the last Nazi war criminal of the Nuremberg trials was found dead in a prison built for hundreds, yet for two decades, housed only him. The official verdict was suicide, a straightforward end to a life defined by fanaticism, delusion, and contradiction.

But the simplicity of the report belied the complexity of the man and the 46 years he had spent in Allied custody. In the meticulously controlled

Did The Nazis Develop Nuclear Weapons? – Mythbusting Berlin

The Nazi obsession with super-weapons became so serious in the closing stages of the Second World that Adolf Hitler personally believed that such ‘Wunderwaffen’ both existed in a usable form – and would save the country from defeat. Had the Nazis managed to develop nuclear weapons by 1945 – the outcome of the war would surely have been different. But how close were Hitler, Himmler, and his henchmen to developing an A-bomb?

Did The Nazis Invent Decaf Coffee? – Mythbusting Berlin

Persistent rumors claim that Nazis preferred their coffee anything but pure, leading some to wonder if they might have influenced the development of decaffeinated coffee. Although decaf was already widely available across Europe by the mid-20th century, speculation continues: could the Nazis really have played a role in popularizing—or even discovering—this caffeine-free alternative, or is this simply another caffeinated conspiracy cooked up to sensationalize an ordinary historical detail?

Did The Nazis Invent The Bicycle Reflector? – Mythbusting Berlin

The fruits of wartime ingenuity are plenty – so many, in-fact, that it has become somewhat of a worn cliche that as the guns start firing the innovators get to work, often solving problems while providing more problems for the enemy to overcome.The kind of progress that results in the production of newer improved, more lethal weapons, such as to increase the chances of victory.

Did The Nazis Run The Largest Counterfeiting Operation In History? – Mythbusting Berlin

During the Second World War the Nazis masterminded an astonishing plot to destabilise Britain by flooding its economy with counterfeit banknotes. Crafted in secret by concentration camp prisoners, this forged fortune became the most ambitious counterfeiting operation ever attempted. But was it history’s largest? Dive into the extraordinary tale of Operation Bernhard,

rife with deception, survival, and intrigue—revealing the truth behind one of the Third Reich’s most audacious schemes and its surprising legacy.

Did The Second World War End In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

When is a war ever truly over? When the last shot is fired in anger would seem like the best measure. Rarely, though, is it possible to gain insight into such a moment.

Remarkably, a record still exists of such a moment at the end of the First World War on the Western Front. A seismic register and recording of the last belching battery of British guns firing artillery across no-man’s-land, followed by a profound

Did The Spanish Flu Pandemic Help The Nazis Take Power? – Mythbusting Berlin

The devastating Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918-1919 struck amid Germany’s post-war turmoil, compounding social instability, economic hardship, and widespread political disillusionment. Could this catastrophic health crisis have indirectly paved the way for Nazi ascension? While often overshadowed by war and revolution, the pandemic’s profound psychological and societal impacts arguably contributed to the perfect storm, enabling extremist ideologies—including Nazism—to gain popularity and ultimately seize power in a fractured Germany.

Have Adolf Hitler’s Remains Been DNA Tested? – Mythbusting Berlin

In the smouldering ruins of Berlin in 1945, the world’s most wanted man vanished. Did Adolf Hitler, as official history attests, die by his own hand in the Führerbunker? Or did he escape, fuelling a thousand conspiracy theories that have echoed for decades? For years, the Soviets claimed to hold the gruesome proof of his death: a skull fragment and a set of teeth, locked away in Moscow archives. But in an age of definitive

How Did The Nazi Concentration Camps Differ From The Soviet GULAG?

The Nazi concentration camps and Soviet Gulag system have often been conflated in popular imagination—twin symbols of twentieth-century totalitarian horror. Yet the two systems operated on fundamentally different principles. One extracted labor to fuel industrialisation while accepting mass death as collateral damage; the other evolved into purpose-built machinery of genocide. Understanding these distinctions isn’t merely academic—it reveals how different ideologies produce different atrocities, and why Germany and Russia reckon with these legacies so differently today.

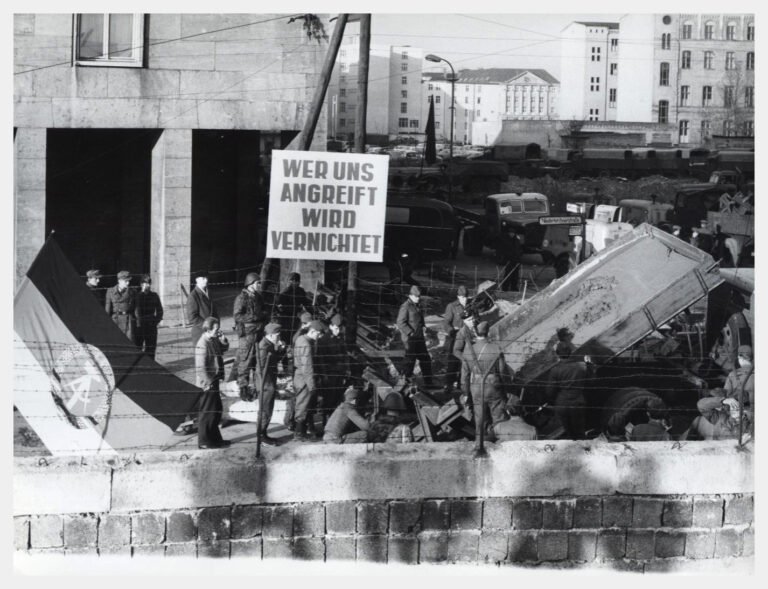

How Long Did It Take To Build The Berlin Wall? – Mythbusting Berlin

It is one of the most enduring images of the 20th century: a city divided overnight. The popular narrative tells us that Berliners went to sleep in a unified city and woke up in a prison. While the shock of August 13th 1961, was very real, the idea that the ‘Wall’ appeared instantly is a historical illusion. The physical scar that bisected Berlin was not a static creation, but a living, malevolent beast that evolved

How Many Assassination Attempts On Adolf Hitler Were There? – Mythbusting Berlin

Nazi leader, Adolf Hitler, projected an aura of invincibility, a man of destiny shielded by providence. But behind the carefully constructed image of the untouchable Führer lies a story of constant threat, of bombs that failed to detonate, and errant bullets that missed their mark. Unearth the hidden history of the numerous attempts on Hitler’s life as we explore the courage of those who tried to change the course of history and the devil’s luck

How Many Jews Died In The Holocaust? – Mythbusting Berlin

The answer to the question posed of how many Jews died in the Holocaust is a simple one: too many. That merely one death was an unforgivable obscenity is a fundamental and necessary realisation in understanding the capriciousness of this unparalleled racial genocide. To comprehend, however, the full number of Jews murdered in Europe by the Nazi regime in the 1930s and 1940s is a detective story of epic proportions: the evidence overwhelming, multifaceted, and

How Many People Died Trying To Escape East Germany? – Mythbusting Berlin

The image of the Berlin Wall is seared into our collective memory, a concrete symbol of Cold War oppression. We think of the daring escapes and the tragic deaths of those who failed. But that well-known number is only a fraction of the truth. The story of those who died trying to escape East Germany is far broader and more complex than most imagine, stretching along a thousand-kilometer border and out into the cold waters

How Old Is Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

A relatively new arrival in Europe, Berlin is over 1000 years younger than London, nevermind Rome or Athens, Jerusalem or Jericho. Just how old is Berlin though?

A question fraught with false assumptions and distortions – that has more often than not been answered with propaganda as it has with the cold hard truth.

Was Adolf Hitler A Drug Addict? – Mythbusting Berlin

Solving the enigma of the ‘Führer’ has become a preoccupation for many, since the arrival of the Austrian-German onto the world stage – although moving beyond the mythology without falling into the trap of prejudically extrapolating on the psychopathography of Hitler or demonising so as to excuse his actions has proven problematic. What to make of the man who became more than the sum of his masks? The painter; the military dilettante, the mass murderer,

Was Adolf Hitler A Freemason? – Mythbusting Berlin

History abhors a vacuum, but adores a mystery. Such is the speculative fiction suggesting a secret allegiance behind the rise of the Third Reich – that the catastrophe of the Second World War was orchestrated from the shadows of a Masonic lodge. The image of Adolf Hitler—the drifter from Vienna turned dictator—as a covert initiate of the very brotherhood he publicly reviled, however, creates a paradox that collapses under scrutiny. As when we unlock the

Was Adolf Hitler Gay? – Mythbusting Berlin

In the shadowy corridors of Third Reich history, few questions provoke as much tabloid curiosity and scholarly exasperation as the sexuality of Adolf Hitler. For decades, rumors have swirled—whispered by political enemies in 1930s Munich, psychoanalyzed by American spies in the 1940s, and sensationalized by revisionist authors today. Was the dictator who condemned thousands of men to concentration camps for “deviant” behavior hiding a secret of his own? By peeling back the layers of propaganda,

Was Adolf Hitler Jewish? – Mythbusting Berlin

Was the dictator who orchestrated the murder of millions of European Jews secretly one of them? It is perhaps the darkest irony imaginable, a story whispered for decades in backrooms, bars, and conspiracy forums alike. The most-common rumour – the ‘Frankenberger Myth’ – suggests that Adolf Hitler’s paternal grandfather was Jewish, a secret so damaging it could have unraveled the entire Nazi regime. But where does this claim come from? And, more importantly, is there

Was Currywurst Invented In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

Explore the story behind what many consider Berlin’s most iconic snack—the ever-so-humble Currywurst. Often hailed as an enduring symbol of culinary creativity amid Cold War scarcity, this humble dish has inspired fierce debate about its true origin. But was it genuinely invented here in Berlin, or have proud locals simply adopted and elevated this spicy street-food favorite into legendary status all their own?

Was Fanta Invented By The Nazis? – Mythbusting Berlin

As one of the most secretive organisations in the world, the Coca Cola corporation refuses to share its secret recipe with anyone. Famously insisting only on shipping the base syrup of its drinks to plants around the world to be carbonated and distributed.

This combined with the trade limitations of the Second World War may have led to the introduction of one of the most popular soft-drinks in the world. But could it be true:

Was Frederick The Great Gay? – Mythbusting Berlin

Frederick II of Prussia, better known as Frederick the Great, is often remembered as the archetypal enlightened monarch – a brilliant military commander, patron of the arts, and learned philosopher. Yet behind the stern portraits of this 18th-century warrior-king lies a personal life long shrouded in intrigue and speculation. Intrigue around the king’s sexual orientation has persisted through the centuries, chiefly revolving around one question: Was Frederick the Great gay?

Was Henry Ford A Nazi? – Mythbusting Berlin

US auto tycoon, Henry Ford, holds the ignominious distinction of being the only American Adolf Hitler praised by name in his National Socialist manifesto: ‘Mein Kampf’. This was not, as it turns out, the only connection between Ford and the Party of Hitler, Himmler, and the Holocaust.

Ford’s overt affinity with the Third Reich reveals a troubling past. How deep these connections ran, and how consequential they were for both sides, is a chapter

Was The Colour Blue Invented In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

Tracing the true history of blue—from ancient Egyptian dyes to the accidental discovery of Prussian Blue in a Berlin lab. We’ll debunk myths about seeing blue, explore colonial indigo plantations, scale mountains with a cyanometer, and trace Van Gogh’s starry skies—all to answer one question: how did Berlin shape our understanding of the world’s rarest color?

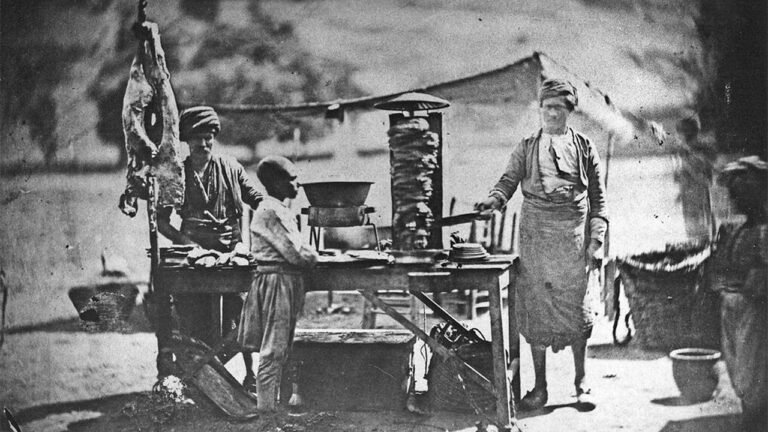

Was The Döner Kebab Invented In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

Unlikely icon of immigrant success; fast food symbol of the working class; over-hyped midnight disco eat; or culturally appropriated cuisine? Its influence goes far beyond layers of seasoned meat and fresh vegetables stuffed into pita bread. But does Berlin deserve credit as the Döner Kebab’s true birthplace, or has the city merely refined and popularized a culinary tradition imported from elsewhere?

Was The Fall Of The Berlin Wall An Accident? – Mythbusting Berlin

On a seasonally crisp night in November 1989, one of the most astonishing events of the 20th century occurred. After twenty eight years, three months, and twenty eight days of defining and dividing the German capital, the Berlin Wall ceased to exist – at least in an abstract sense. Although the removal of this symbol of the failure of the East German system would take some time, its purpose – as a border fortification erected

Was The Nazi Party Democratically Elected? – Mythbusting Berlin

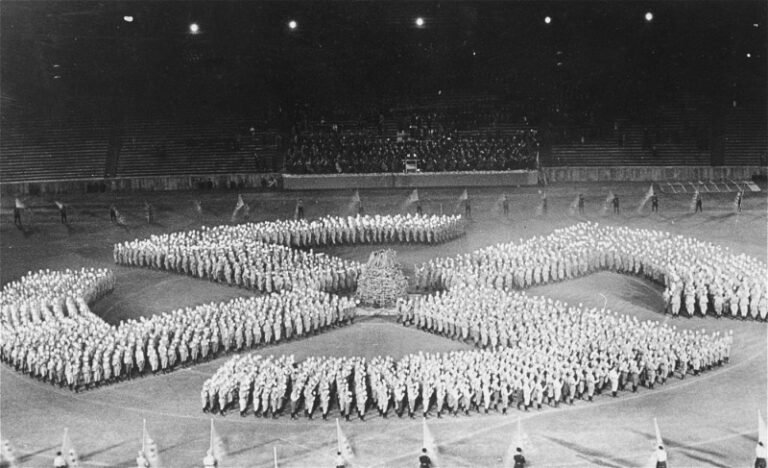

The myth persists that Adolf Hitler rose to power through popular democratic choice. Yet history reveals a darker, more complicated truth. Hitler’s ascent involved exploiting democratic institutions, orchestrating violence, propaganda, and political intrigue—not a simple election victory. Understanding how Germany’s democracy collapsed into dictatorship helps illuminate the dangerous interplay between public desperation, elite miscalculations, and extremist ambition, providing crucial lessons for safeguarding democracy today.

Were The Allied Bombings Of Germany War Crimes? – Mythbusting Berlin

The history of the Allied bombing of Germany during the Second World War still triggers fierce debate. Was reducing cities to rubble a necessary evil – justice from above in a just war – or an unforgivable crime? Can the intentional targeting of civilians ever be justified as militarily necessary?

In a conflict where all rules seemed to vanish, an even more pertinent question persists: by the very standards they would use to judge their

Were The Nazi Medical Experiments Useful? – Mythbusting Berlin

Before the Nazi period, German medicine was considered the envy of the world – a shining monument to progress. But deep within that monument, a rot was spreading, one which would collapse the entire structure into an abattoir. From the wreckage, we are left with a profoundly uncomfortable inheritance: a moral enigma wrapped in doctor’s whites.

What to make of the data, the images, and the terrible knowledge gleaned from unimaginable human suffering. Whether

What Are The Origins Of The Nazi Salute? – Mythbusting Berlin

A specter is haunting the modern mind, a gesture so charged with the dark electricity of history that its mere depiction can unleash a storm of controversy.

It is a simple movement: the right arm, stiff and straight, raised to the sky. But in that simplicity lies a terrifying power, a symbol of a regime that plunged the world into an abyss and a chilling reminder of humanity’s capacity for organised hatred.

This

What Are The Origins Of The Nazi Swastika? – Mythbusting Berlin

Long before the legions of the Third Reich marched beneath its stark, unnerving geometry, the swastika lived a thousand different lives. It was a symbol of breathtaking antiquity, a globetrotting emblem of hope and good fortune that found a home in the most disparate of cultures. To even begin to understand its dark 20th-century incarnation, one must first journey back, not centuries, but millennia.

What Are The Pink Pipes In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

A first-time visitor to Berlin could be forgiven for thinking the city is in the midst of a bizarre art installation. Bright pink pipes, thick as an elephant’s leg, climb out of the ground, snake over pavements, arch across roads, and disappear back into the earth. Are they part of a complex gas network? A postmodern artistic statement? A whimsical navigation system? These theories, all logical, are all wrong. The truth is far more elemental,

What Do The Colours Of The German Flag Symbolise? – Mythbusting Berlin

What does a flag mean? Is it merely a coloured cloth, or does it hold the hopes, struggles, and identity of a nation? The German flag, with its bold stripes of black, red, and gold, is instantly recognisable. But the story of its colours is a tumultuous journey through revolution, suppression, and reinvention. The common explanation for their symbolism is a simple, romantic verse, yet the truth is a far more complex and contested tale,

What Happened To Adolf Hitler’s Alligator? – Mythbusting Berlin

It is often said that you can tell a lot about a person by their relationship with animals; that owners often come to look and behave like their pets. Or is it perhaps more that people choose their pets to correspond to their personality? Nazi leader Adolf Hitler’s love of dogs, for example, is well documented but what is there to make of his relationship with reptiles?

What Happenened To The German Royal Family? – Mythbusting Berlin

When the smoke cleared over the trenches in November 1918, the German Empire had evaporated, and with it, the divine right of the Hohenzollern dynasty. Conventional wisdom suggests the family simply vanished into the sepia-toned obscurity of history books—exiled, forgotten, and irrelevant. But dynasties, like weeds in a landscaped garden, are notoriously difficult to uproot entirely. The story of the German royals did not end with the Kaiser’s flight to Holland; it merely shifted gears.

What Is The Difference Between Fascism & Nazism? – Mythbusting Berlin

While the terms ‘Fascist’ and ‘Nazi’ are often bandied around interchangeably as shorthand for tyranny – Italian fascism and German National Socialism were distinctly different beasts. Albeit ideological kin. One an ideology of state-worship, born from post-war chaos and national pride; the other built upon a fanatical, pseudo-scientific obsession with race. Two peas in the same totalitarian pod – twins in tyranny – more succinctly summarised as the Nazi chicken to the Fascist egg.

What Was Checkpoint Charlie? – Mythbusting Berlin

Checkpoint Charlie remains among Berlin’s most visited historical sites, famed worldwide for its significance during the Cold War. Originally established as a modest border-crossing point, it evolved dramatically over the decades into an international symbol of freedom, espionage, and intrigue. Today, critics and locals often dismiss it as little more than a tourist trap—Berlin’s Disneyland—but how exactly did Checkpoint Charlie get its peculiar name, and what truths hide behind its popularity?

What Was Prussia? – Mythbusting Berlin

Prussia’s legacy is both remarkable and contentious—once a minor duchy, it rose dramatically to shape modern European history. Renowned for military discipline, administrative efficiency, and cultural sophistication, Prussia was instrumental in uniting the German states, laying foundations for a unified Germany. But how did this kingdom, with its roots in Baltic territories, achieve such prominence, and why does its complex history continue to evoke admiration, debate, and occasional discomfort in Germany today?

What Was The Berlin Airlift? – Mythbusting Berlin

In the ruins of 1948, the silence of Berlin was not a sign of peace, but a held breath before a new catastrophe. The city, drowning in rubble and political intrigue, became the staging ground for the twentieth century’s most audacious gamble. While popular history remembers the chocolate parachutes and smiling pilots, the reality of the Berlin Airlift was a terrifying operational nightmare born from a ruthless currency war. It wasn’t just a humanitarian mission;

What Was The Socialist Kiss? – Mythbusting Berlin

It is one of the most curious and enduring images of the Cold War: two middle-aged, grey-suited men, locked in a fervent embrace, their lips pressed together in a kiss of apparent revolutionary passion. This was the ‘Socialist Fraternal Kiss’, a ritual that, for a time, seemed to encapsulate the unwavering solidarity of the Eastern Bloc.

But what was behind this seemingly intimate gesture? Was it a genuine expression of camaraderie, a piece of

Who Built The Berlin Wall? – Mythbusting Berlin

One of the most common questions I have encountered from people curious about Berlin, and often so cryptically phrased. Who built the Berlin Wall? A simple five-word query, yet one that can be read one of two ways. More than thirty years since the ‘Fall of the Wall’, the story of its construction continues to baffle many who are mainly familiar with its existence through knowledge of its importance…

Who Really Raised The Soviet Flag On The Reichstag? – Mythbusting Berlin

One iconic photograph has come to symbolise the Red Army’s victory over Nazi Germany in 1945—the Soviet flag waving triumphantly above Berlin’s battered Reichstag building. Yet behind this enduring image lies controversy, confusion, and political manipulation. Who truly raised the Soviet banner atop the Reichstag? Was it a spontaneous act of heroism or carefully staged Soviet propaganda? Decades later, unraveling the truth reveals surprising layers beneath the mythologized symbol of Soviet triumph.

Who Was Really Responsible For The Reichstag Fire? – Mythbusting Berlin

Various theories have been posited as to who actually set fire to the German parliament in 1933. Was it the opening act in an attempted Communist coup or a calculated false flag operation carried out by elements of the Nazi Party, intended to create the conditions necessary for introducing single-party rule? And what part did the young man from Holland, arrested shirtless inside the building the night of the fire, play in this event?

Who Were The Last Nazis On Trial? – Mythbusting Berlin

More than eighty years after the Holocaust, courtrooms across Germany still echo with testimony from the final chapter of Nazi justice. Centenarian defendants in wheelchairs, their faces hidden behind folders, arrive to answer for crimes committed in their youth. These are not the architects of genocide—those men faced their reckoning at Nuremberg decades ago. These are the guards, the secretaries, the bookkeepers: ordinary people who enabled extraordinary evil. Their trials represent a legal revolution: the

Why Is Berlin The Capital Of Germany? – Mythbusting Berlin

There was little in its humble origins—as a twin trading outpost on a minor European river—to suggest that Berlin was destined for greatness. It sits on the flat expanse of the North European Plain, a landscape once dismissively referred to as the “sandbox of the Holy Roman Empire.” Unlike other world capitals, it lacks breathtaking scenery or a naturally defensible position. It is a city built not on majestic hills or a grand harbour, but