“If beef’s the king of meat, potato’s the queen of the garden world”

Irish saying

When in 1951, American starlet Marilyn Monroe was dressed down by a catty critic as only being beautiful because of her clothes, her response was to organise a photo shoot wearing a burlap potato sack – and in doing so prove an important point: that the side dish can be truly awful, as long as the main course makes your mouth water.

German cuisine is not generally known for its mouth watering main courses – nor its inspiring side dishes either, where potato seems to feature prominently. Although any allegory of Marilyn Monroe soon falls apart when we consider that the burlap sack may indeed represent potatoes, but the part of Monroe on a German plate is almost exclusively played by a stonking great piece of pork.

Hardly flattering. Even when dolled up in diamonds and heels.

Take note of the three pork and potato dishes mentioned in the opening paragraph – which may be considered ‘German’ but are of varied origin themselves.

- The Schnitzel, which is claimed by Austria in its Viennese form, while having imitators and potential predecessors elsewhere – typically comes served with fried potatoes in Germany.

- The Schweinshaxn, an oven roasted pork knuckle popular in the south-eastern Bavarian region of Germany, usually found with potato salad.

- And last but not least, Königsberger Klopse – a meatballs dish traditionally made with veal and pork served in capers sauce with boiled potatoes, named after the coronation city of the Prussian Kings, now known as Kaliningrad and a semi-exclave of the Russian Federation.

Three dishes united in their utilisation of the humble potato (if we are to make one assumption about German cuisine it would be that it often comes with potato).

But three dishes also from a time before Germany existed.

An important point to bear in mind here, whilst we consider the matter of the potato and its provenance.

We can swiftly deal with one misapprehension when questioning what part Frederick the Great played in popularising the spud in Germany.

That of chronology.

Germany as we think of it now would not really exist until 1871 – when the country was first united following the defeats of Denmark, Austria, and France at the hands of Prussia and its allies. As such, during Fredrick the Great’s rule – from 1740 until 1786 – it would have been impossible for him to introduce the potato to ‘Germany’ per se.

Perhaps better then in our inquiry to consider whether Fredrick could be seen as being responsible for introducing the potato to his Kingdom of Prussia – and how, if that were the case, that affected the popularity of the potato on the European continent.

As to talk of Germany before its unification in 1871 would be comparable to talking of modern day Latin America – a region identifiable by its shared language and culture, although not gathered under one flag; or into one unified state.

Fittingly, it was from what we now know as the largest part of Latin America – South America – that the first potatoes arrived on European shores.

–

The Potato-Non-Grata

“Those who would give to the Spaniards the honour of entrencing (sic) this useful root called the potato, give me leave to call designing parricides, who stirred up the mislead zeal of the people of this kingdom to cast off the English government which is the greatest mercy they ever enjoyed… To ascribe the honour of the English industry to the effeminate Spaniards cannot be passed over without remark… and if I might advise the inhabitants, they should every meal they eat of this root be thankful to the Creator for English navigation.”

Anglo-Irish botanist Caleb Threlkeld

Although domesticated around 7,000-10,000 years ago, potatoes were not introduced to Europe until the mid-16th century – by Spanish explorer Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada. Quesada returned from South America in 1565 after encountering the vegetable, along with the people of the Muisca Confederation, on his search for El Dorado – the man, the city, the kingdom, or interchangably the empire of gold (depending on who was believed at the time).

This conquistadorial connection is still evident in the English word for the potato, which comes from the Spanish term ‘patata’.

It is still sometimes said that Elizabethan-era English explorers Walter Raleigh and Francis Drake were actually responsible for introducing the potato to Europe – although this is known to be demonstrably false.

Raleigh certainly played a significant role in popularising tobacco in Great Britain but his earliest expedition, in 1578, took place well after Spanish explorer Quesada had already returned to Europe bearing the fruits – and vegetables – of his travels. Similarly, Drake returned in 1580 – seven years after the Hospital de la Sangre in Seville, Spain was already buying potatoes as part of their regular housekeeping.

To the contrary, it could in-fact be argued that Sir Walter Raleigh did more harm than good – as far as the potato is concerned – after reportedly gifting a batch of spuds to Queen Elizabeth I for a banquet in 1586. The kitchen staff mistakenly cooked the flowers and threw the potato away; leaving the guests worse for wear and Elizabeth thoroughly unimpressed with this dirty vegetable.

Like the tomato, the potato is a nightshade and the vegetative and fruiting parts contain a toxin which is dangerous for human consumption.

No surprise then that after its arrival in Europe, it was mainly considered fit only to be used as animal feed or the body of the potato discarded so the flowers could be used for decoration. Some religious authorities even deemed the potato unsuitable for human consumption – as it was not mentioned in the Bible – earning it the nickname, the ‘Devil’s Apple’.

Much has changed in the last five hundred years: there are now around 5,000 different types of potatoes available worldwide, making the these starchy tubers the fourth largest crop on the planet – after maize, wheat, and rice.

In 1995, potato plants were even taken into space aboard the space shuttle Columbia – marking the first time any food was ever grown off-planet.

Back in the 16th century, however, peasants in Spain would initially only resort to eating the potato as a way of staving off famine. Much of the Spanish landscape was too dry for potatoes to take but in a few isolated areas of northwest Spain, the potato soon began to flourish. Basque fishermen were known to use them as ship stores for their Atlantic voyages and would come ashore in Ireland to dry their catch – likely introducing the potato there when returning from the Grand Banks of Newfoundland.

Of the four blockbuster crops – wheat, potatoes, maize, and rice – it would be wheat (sometimes referred to as ‘corn’ in the English speaking world) that would be the initial dietary driving force behind European growth – until the arrival of the potato poured gasoline on that fire.

Wheat had spread westerwards through Europe from the regions of the Fertile Crescent around 8500BC – bringing with it high yields and a crop that could be easily harvested and stored.

The domestification of this important source of carbohydrates, that is also relatively high in protein, would faciliate the transformation of human society from dispered nomadic hunters to settled villagers. The most valuable crop in the modern world – bread wheat – which originates from the Fertile Crescent in hybrid form, would not only feed peasants and kings – but allow farmers to operate beyond subsistence level and become self sufficient – producing a surplus for trade.

Reliance, however, on a single crop – and one that can be so easily stolen once it is processed and stored – would prove far from ideal. Bread never disappeared from the diet of the north European population, but the arrival of the potato would eventually displace it as the principal food of the poorer classes. The introduction of the potato to European gardens and fields provided a much needed additional food source. They were cheaper, required less preparation, and per acre provided a higher caloric yield more than twice that of wheat.

Spanish ships would carry potatoes to Italy, where they would start growing in the gardens of the Po valley by about 1560; soldiers moving across the European continent – from Italy to the Rhineland and Low Countries along the ‘Spanish Road’ – would bring potatoes with them, that would take root wherever they set foot.

Natural suspicion of this alien food – compounded by fears stoked by religious authorities – would soon be outweighed by the ability of potatoes to keep a family alive on a war ravaged continent where military seizure of wheat meant that wherever a local population relied on stored grain for survival, outright starvation was the usual and expected result.

During the Austrian Wars of Succession (1740-1748), Prussian King Frederick the Great would realise how important potatoes were to keeping his peasants alive – organising distribution of free seeds throughout his Kingdom with instructions on how to grow them. As a consequence, even when Prussia was on its knees during the Seven Years War (1756-1763), fighting against a coalition of French, Russian, and Austro-Hungarian troops, Prussian peasants were still able to escape disaster by eating potatoes.

A food of last resort would soon be transformed into a staple; and acutely aware of the benefits that the humble potato offered in extending the northern European food supply, Frederick the Great would embrace ‘the Devil’s Apple’.

–

'Der Kartoffelkoenig' - Frederick the Great

“You are to make the benefit of planting this crop clear to the lords and subjects, and advise them to undertake the planting of potatoes this early year as a very nutritious food…Wherever there is an empty space, the potato should be cultivated, since this fruit is not only very useful to use, but also so productive that the effort put into it is very well rewarded.”

Frederick the Great’s Potato Order of March 24th 1756

In order to fight, every army has to be fed and the movement of armies during Frederick the Great reign in the 1700s would require a huge logistical effort. Food stuff had to be procured, not only for the fighting men but also their horses. To embark on a campaign with the intention of living out of the country was considered only a last resort – preparation would be key to any military victory.

Like most armies in the 1700s, the Prussian army largely relied on bread – but this could not be taken on long campaigns as it would spoil quickly, so instead flour would be transported and bakeries established in the field.

For the Prussian soldier a bread portion for one day was 1kg. To bake 100kg of bread, 75kg of flour were needed. For an army with an entitlement of 100,000 portions of bread, the daily requirement of flour was more than 70,000kg. Additional to this was the meat ration provided, spirits, and vegetables; but once the bread supply was assured, a commander could largely plan his future operation without particular feeding concerns.

For the time, the Prussian soldier was treated better than soldiers in other armies: the Austrian soldier had to pay for his meat ration; which usually acted as an inducement for desertion to the Prussian side. The Russian soldier would not receive bread but be simply given flour, which he would knead into dough and place into an individual fire hole to make his own bread.

Frederick would level off against both of the French and Russian armies during the Seven Years War (1756-1763) and as a result of a French blockade on grain imports began to place more emphasis on a vegetable that had arrived in the region around one hundred years before he took the throne, but had been largely neglected: the potato.

Transporting potatoes would not be easier than transporting flour but finding an alternative crop to wheat for his peasants would also free up more for his army to make into flour.

Frederick’s great grandfather – Elector Frederick William (‘The Great Elector’) – had brought the potato to Prussia, after encountering it in Bavaria – where it was being used as an ornamental plant.

According to historian Jürgen Luh, author of Der Grosse Kurfürst, the wife of the Great Elector of Brandenburg, Luise Henriette, grew potatoes on her small Botzow estate for some time before realising that this exotic delicacy was edible and tasty when prepared properly. As a result potatoes would be introduced to the garden of the Berlin Palace for consumption around 1655 – but take much longer to graduate from the botanical garden to the kitchen table outside royal circles.

It would take state intervention to make this happen; as field agriculture in Prussia was strictly governed by custom that prescribed seasonal rhythms for plowing, sowing, harvesting and grazing animals.

One hundred years after the introduction of the potato to the Berlin Palace, on March 24th 1756, Frederick the Great issued an order to hugely increase potato crops for consumption within his country – it would be one of fifteen such decrees regarding potatoes issued in his lifetime.

Tim Blanning, author of the biography of Frederick the Great that shares the King’s name, notes the increased interest in potatoes during the Frederick’s reign.

“One special concern, almost an obsession, was the promotion of the potato as a field crop…This was eminently sensible, for the potato was European agriculture’s most powerful weapon in breaking the age-old overdependence on grain as the staple crop.”

Frederick himself did not know the potato from his youth – he had been raised on barley and grain porridge, cabbage, and beer soup. He is said to have become acquainted with it at the court of his sister Wilhelmine in Bayreuth and to have immediately recognized its importance for the nutrition of the Prussians.

“It has been estimated that in the eighteenth century the yield of the potato per acre was 10.5 times higher than wheat and 9.6 times higher than rye, which more than compensated for its lower caloric value.To put that statistic another way, the net caloric value of a potato is 3.6 times that of grain. It has been estimated that ten square meters of land would produce 500 kilocalories in meat, 2,000 in cereals, 6,300 in cabbage, and 7,200 in potatoes.”

Modernising Prussia was one of Frederick’s life-long priorities, when not out fighting with his army – as he set about transforming his kingdom from a European backwater to an economically strong and politically reformed state. A policy of agricultural reform would be an integral part of this elevation of his entire state and his subjects. Frederick was intrigued by almost every aspect of life in his kingdom – but would take a particular interest in agriculture, saying that “True wealth is only what the earth produces” and “Agriculture is the first of all arts.”

Around a thousand new villages would be established in Prussia during Frederick the Great’s rule, bringing more than 300,000 new people to the land. Taming and conquering nature, which, in its wild form, Frederick regarded as useless and barbarous, was of great importance, and through undertaking a massive drainage program Frederick created roughly 150,000 acres of new farmland in the Kingdom’s Oderbruch marshland. Farmers were advised to grow potatoes and turnips in order to prevent a famine in Prussia – but the king had trouble making his potatoes palatable to his peasants. Frederick coined the phrase ‘Potatoes instead of Truffles!‘ and launched a propaganda campaign for the subterranean field crop.

Still not everyone was convinced.

The people of the town of Kolberg, for instance, officially replied to the King’s order to grow potatoes by saying:

“The things have neither smell nor taste, not even the dogs will eat them, so what use are they to us?“

Rumour is that Frederick responded by threatening to cut off the ears and tongues of the people of Kolberg – although this did not happen.

One of the most oft-repeated stories about Frederick’s relationship with the potato concerns the ingenious tactic of reverse psychology the King embarked on to increase interest in potatoes: rebranding it as a ‘royal vegetable’. By ordering his soldiers to plant potatoes in royal fields and lightly guard the crops, allowing the locals to sneak in and pillage the vegetables – the Prussian king would conclude: what is worth guarding is also worth stealing.

Whether this detail is true or not is still debated – Kurt Winkler, the Director of the Haus of Brandenburg-Prussia History claims that this story is older and actually originates in France, an assertion which brings with it its own problems.

Transforming the humble potato into a dish fit for a king also meant serving numerous courses of various preparations in his own household – whilst loudly consuming them in front of his guests.

His meddling with the diet of his subjects did not stop with potatoes – Frederick would famously demand that his subjects drink beer instead of coffee, in order to protect the Prussian brewing industry. Aware that self-sufficiency was preferable to relying on imported coffee from his rivals. Mulberry trees would also be planted to obtain silk, which was important for the domestic textile industry.

Frederick may have been a leader with a botanical vision – but he was first and foremost a feared military strategist – said to have acquired his sobriquet from his enemies who were so fearful of his military prowess.

In the last decade of his life he would embark on a campaign that would see his precious potato utilised in a way that until this point had been alien in European conflict – as a staple foodstuff crucially used to extend the time his army could spend in the field and ensure a tactical advantage.

The man who had built his international reputation through his military campaigns would be outshone in his old age – by the humble potato.

–

The Potato War Of Bavarian Succession

“Il faut surtout penser à vos subsistances, car une armée est un corps dont le ventre est la base; a quelque beau dessein que vous ayez imaginé, vous ne pourrez pas le mettre en exécution, si vos soldats n’ont pas de quoi se nourrir.”

“You must always keep in mind your supplies, for an army is a body whose belly is the base; whatever nice goal you might have imagined, you won’t be able to put it into execution, if your soldiers do not have something to feed themselves.”

Réflexions sur les projets de campagne, 1775

Frédéric II (Frederick II – Frederick the Great)

1775 was a terrible year for Frederick the Great. He finally lost too many teeth to be able to play his beloved flute. He would also have a series of attacks of gout and be tormented by abscesses in his ear and on his knee. He would live for another eleven years – but his few remaining friends were all dying around him.

Worse still, the political situation in Europe appeared much as ragged as Frederick’s body.

Hearing of the King’s frail condition, the Emperor Joseph of Austria-Hungary – who had taken the throne ten years earlier and served as co-regent with his mother Maria Theresa – sent an army to Bohemia, threatening to invade Brandenburg and Frederick’s lands on his death. The Austrian aim: retake the region of Silesia – Frederick’s first military conquest in 1740.

As Christopher Clarke points out in Iron Kingdom, the Austrians rightly viewed Silesia as a “dagger poised at the heart of the Habsburg monarchy”. It would be from these eastern territories that the Prussian forces would pounce in 1866, finally settling the matter of hegemonic control over the German speaking world once and for all.

In 1752, Frederick summarised the discontent oozing from Vienna: “Never will Austria get over the pain of Silesia’s loss. Never will it forget that it must now share its authority in Germany with us.”

The Austrians had already shown their expansionist intentions in 1770 when their seizure of two estates in Poland – ostensibly to stop the spread of plague – had triggered a rush to butcher the country and seen Prussia, Russia, and Austria-Hungary engage in the First Partition of Poland.

The death of the Elector of Bavaria, Maximilian III Joseph, from a virulent strain of smallpox in 1777 brought about the territorial expansion that Fredrick had feared, when the Austrians decided to compensate themselves for the loss of Silesia by annexing Bavaria. His natural successor, Charles Theodor, had agreed with Vienna to exchange his potential control of Bavaria for the Austrian Netherlands (Belgium).

The bipolar balance of power between Prussia and Austria in the 1700s had been disturbed.

The remaining German states viewed the Austrian annexation of Bavaria as a predatory power play by the House of Habsburg but the only European leader with the military strength – and interest – to intervene at this time was Frederick the Great.

Thus began one of the strangest military campaigns in Prussian history.

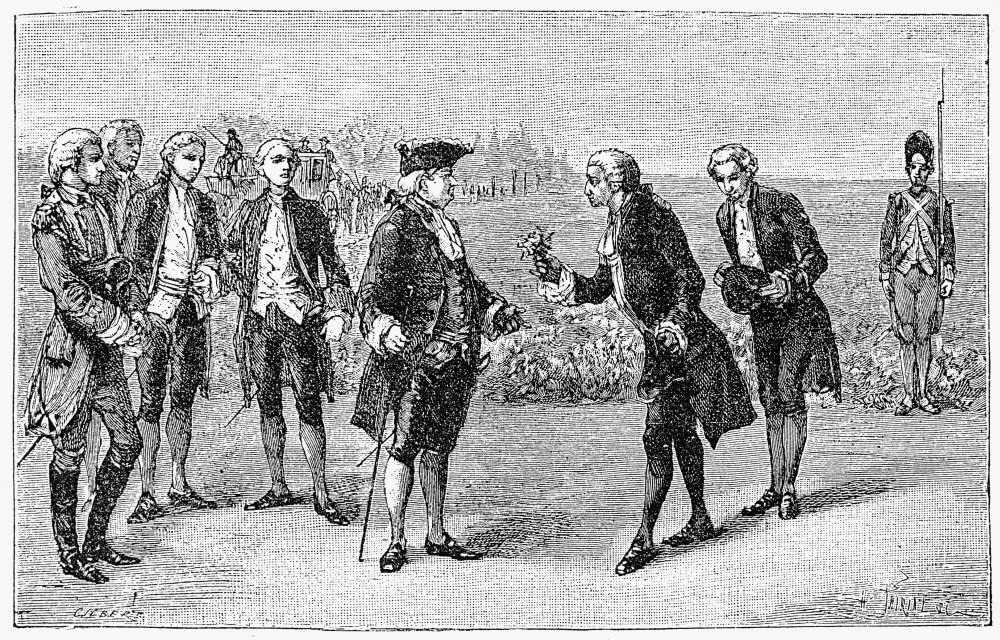

Frederick – at age sixty-six – was far too frail to lead his army but entirely opposed to Austrian expansion he mobilised his troops anyway. He would claim to be acting on behalf of the rival heir of Bavaria, Duke Charles of Zweibrücken, and travel in a coach – taking to a horse when the day of battle arrived.

Frederick left Berlin in April 1778 with an army of 100,000 men – but in his old age, he had lost the taste for war. He would soon be reinforced by 22,000 Saxons supporting their own ruler’s claim to part of Bavaria and with the Austrians scattered could easily have marched on Vienna. Instead, Frederick’s brother Prince Henry moved his forces into Bohemia in July, where a number of skirmishes allowed him to distinguish himself. Frederick’s eastern army entered Moravia and made little progress.

The winter that would follow would involve long months of maneuvering without serious engagement. By spring, the Austrians were simply waiting on one bank of the river Elbe with the Prussian troops opposite.

In October the campaign came to an end without any decisive engagement. The Austrian army had not moved. Alarmed by the shifting balance of European power, Maria Theresa – an opponent to the war – had been writing to Frederick behind her husband’s back and arranged for peace.

The chief business of this conflict had been in the feeding of vast static armies. Something Frederick’s little yellow vegetable had proven suitable for – and the soldiers, who did more foraging that fighting, came to call this the ‘Potato War’.

Potatoes in the soil of large parts of Europe can survive unaffected by frost in the winter, as the ground seldom freezes. Meaning that they can remain in the ground until the spring thaw when they begin to grow again. Foraging parties of soldiers during the ‘Potato War’ would easily harvest potatoes individually from the cold ground where they were essentially being stored, when the granaries were empty of wheat or the flour from the army logistics had been exhausted.

When the ground in Europe does freeze, the potatoes are harder to recover – although it is not impossible – and although the taste and texture is altered through freezing, the nutritional content remains undiminished.

A similar storage technique was being used, albeit intentionally, by the people of the Incan Empire when it was encountered by Spanish conquistadors. Potatoes would be stored in sealed, permanently frozen underground containers where the nutritional content could be preserved for several years.

This mode of food preservation would sustain the growth of the Incan civilisation; and in a less organised way – throughout the winter of 1778/79 – would also allow the Prussian and Austrian armies to remain in the field while their soldiers foraged for frozen potatoes.

With the Treaty of Teschen in May 1779, the Austrians finally gave up their claim to Bavaria and the war came to an end, although they did insist on keeping the rich district of Burghausen.

Thus Frederick saved Bavaria and its independence – with the help of a few potatoes along the way.

–

The French Connection - Antoine Parmentier

“I appreciate the potato only as a protection against famine, except for that, I know of nothing more eminently tasteless.”

Anthelme Brillat-Savarin in ‘The Physiology of Taste’ (1825)

Beyond the reputation he cultivated at home as a modernising and just leader, Frederick the Great longed to be remembered as a Philosopher King, a contemporary in the era of Voltaire, Rousseau, and Diderot. Indeed, like all these Enlightenment era thinkers, Frederick wrote and spoke in French. Leaving his works largely neglected by a Francophone audience suspicious of the old Prussian, and his native German speaking followers who found themselves incapable of deciphering the thoughts of the man who chose to use his foreign tongue.

His westward influence on the French, however lacking in philosophy certainly could be said to have been fruitful in cuisine.

Thanks to the capture of a French army pharmacist during the Seven Years War – a man named Antoine-Augustin Parmentier.

French speakers may be aware of Parmentier from the Parisian metro station that bears his name or the many potato dishes named after him. Crème Parmentier, for instance – a potato and leek soup; hachis Parmentier, a cottage or shepherd’s pie; brandade de morue parmentier, salt cod mashed with olive oil and potatoes; garniture Parmentier, cubed potatoes fried in butter; and most importantly purée Parmentier, mashed potatoes.

Parmentier was imprisoned by the Prussians, under Frederick the Great, and fed potatoes whilst in captivity – considered only suitable as hog feed in France at the time.

In 1748, France had actually forbidden the cultivation of the potato: it stood on trial with accusations that it caused leprosy, syphilis, early death and sterility – not to mention rampant sexuality.

This law would remain in place until 1772. Meaning that while Frederick the Great was convincing his subjects to plant potato crops – and tempting them with his ‘dish fit for a king’, the French were busy missing out on the benefits of this nutritious vegetable.

Enslaved by superstition and pseudo-science.

Permentier returned from Prussian captivity in 1763 and began working in nutritional chemistry – winning an essay in 1771 where the judges actually voted the potato as the best substitute for regular flour.

The year France’s potato law was finally repealed, Permentier proposed the potato as a source of nourishment for dysentric patients, in a contest sponsored by the Academy of Besançon. A contest he would go on to win.

Finally in 1772 the Paris Faculty of Medicine would declare the potato as edible.

Like Frederick the Great, Antoine-Augustin Parmentier would host dinners where potato dishes would feature prominently – even entertaining one of the founding fathers of the United States, Benjamin Franklin. Like Frederick, he would adopt the same strategy of surrounding potato patches with armed guards, only to withdraw them in the night so that people can steal the potato.

Eventually in 1800, Napoleon Bonaparte would appoint Permentier his first army pharmacist – seeing the success of his nutritional adventures.

Permentier recognised the potato’s potential in “reducing the calamities of famine”, his success and ability to almost-single handedly transform the French kitchen would not have happened without his time in Prussian captivity and the influence of Frederick the Great.

In another example of shared destiny, Permentier is buried in the Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris, in a plot ringed by potato plants. Visitors to Frederick the Great’s grave in Potsdam will find a similar sight today, as raw potatoes are left in tribute daily where he rests.

**

Conclusion

Frederick’s Potato Order on March 24th 1756 was the first of its kind in Europe – perhaps the world – an order that potatoes be planted for consumption that would result in a fine if not obeyed.

At the time, the vegetable was still neglected by other European nations – either considered a mere ornament or worse, poisonous or devilish. An outlier crop that through Frederick’s intervention would take its place in the court of the king and the kitchen of the peasant.

It cannot be said that Frederick introduced the potato to Germany – by pure matter of chronology – although his promotion of the potato in Prussia, and the increase in popularity on the continent following his orders certainly had an immense impact.

Had Antoine-Augustin Parmentier not been captured alive by the Prussians or died in captivity, would the French have seen fit to change their minds about the potato?

Frederick the Great’s role in popularising the potato throughout Europe – and as such throughout the world – is undeniable. Although he is not solely deserving of the credit for the way the potato crop changed the world; his place in history is assured.

The potato remains an essential crop in Europe (especially northern and eastern Europe), where per capita production is still the highest in the world. Communist firebrand, Friedrich Engels, even declared that the potato was the equal of iron for its “historically revolutionary role”.

And as William McNeill writes in his study of the potato and its impact:

“It is certain that without potatoes, Germany could not have become the leading industrial and military power of Europe after 1848, and no less certain that Russia could not have loomed so threateningly on Germany’s eastern border after 1891.”

What a difference a spud makes.

***

If you’ve enjoyed reading this article, consider booking one of our private guided tours of Berlin.

Sources

Blanning, Tim (2016) Frederick the Great: King of Prussia ISBN-13 : 978-0141039190

Clark, Christopher (2007) Iron Kingdom: The Rise and Downfall of Prussia 1600-1947 ISBN-13 : 978-0140293340

Diamond, Jared (1999) Guns, Germans, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies ISBN-13 : 978-0393317558

McNeill, H. William (1999) How The Potato Changed The World’s History Social Research Vol. 66, No. 1, FOOD: NATURE and CULTURE

Mitford, Nancy (2011) Frederick the Great ISBN-13 : 978-0099528869

Snodgrass, Mary (2012) World Food: An Encyclopedia of History, Culture and Social Influence ISBN-13 : 978-0765682789

HISTORICAL ARTICLES

Mythbusting Berlin

Are There Any Nazi Statues Left In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

Visitors to Berlin often arrive expecting to find the physical remnants of the tyranny of the 20th century still standing – statues of dictators, triumphal arches, or bronze idols. Instead, they often find none. The stone symbols and statues of the Third Reich are still gazing down on them, however, hiding in plain sight. But why are there no statues of Hitler? Did the Allies destroy them all in 1945, or is the truth stranger

Could The Western Allies Have Captured Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

To contemplate a Western Allied capture of Berlin in 1945 is to challenge the established endgame of the Second World War. What was the true military and logistical feasibility of a Western Allied assault on the Nazi capital? What factors truly sealed Berlin’s fate, and what might have changed had the Allies pushed eastward?

Answering these questions means delving into the complex interplay of logistics, political maneuvering, and the competing visions for a post-war world

Did Any Of The Rothschild Dynasty Die In The Holocaust? – Mythbusting Berlin

The Rothschild name is synonymous with immense wealth, influence, and persistent conspiracy theories—especially during the era of Nazi Germany. Often targeted by antisemitic propaganda, the family’s survival during World War II has sparked myths about their supposed immunity from Nazi persecution. But did any Rothschild family member actually perish in the Holocaust? This article explores that compelling question, unraveling historical misconceptions and revealing the reality behind one of Europe’s most famous dynasties.

Did Frederick The Great Introduce The Potato To Germany? – Mythbusting Berlin

One of the more bizarre claims to fame attributed to the first King of Prussia is that the man who would go down in history known as Frederick the Great introduced the potato to Germany during his reign back in the 1700s. This starchy root vegetable has undoubtedly become a staple part of German cuisine – an essential addition to any plate of Schnitzel, Schweinshaxn, and Königsberger Klopse – however, whether Frederick the Great is

Did Hitler Escape To Argentina In 1945? – Mythbusting Berlin

Although Nazi leader, Adolf Hitler, certainly remains an inescapable figure, could there be any truth to the story of his escape to Argentina in 1945? That the most wanted man on earth could simply vanish, to spend the rest of his life peacefully in South American obscurity captivates imaginations. Yet, despite numerous investigations, this tale persists primarily as myth—fueled by speculation, hearsay, and conspiracy theories.

Did Hugo Boss Design The Nazi Uniforms? – Mythbusting Berlin

The idea that Hugo Boss – the man whose name now adorns expensive suits and fragrances – was the creative genius behind the Nazi uniforms suggests a terrifying collision of haute couture and holocaust – a marriage of high style and high crimes. The image is striking: a German tailor sketching the ultimate villain’s costume. But history, as usual, is far messier, more bureaucratic, and more banal than the internet memes suggest. To understand who

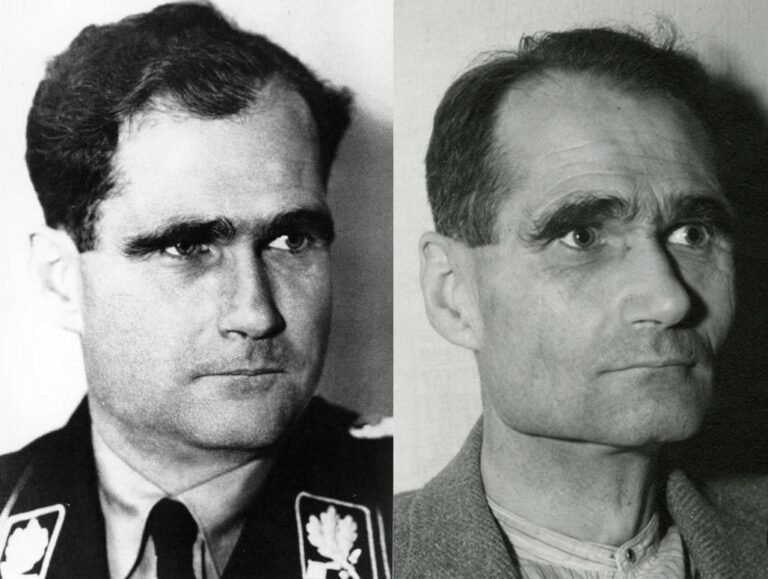

Did Rudolf Hess Really Commit Suicide? – Mythbusting Berlin

On a summer’s day in 1987, the last Nazi war criminal of the Nuremberg trials was found dead in a prison built for hundreds, yet for two decades, housed only him. The official verdict was suicide, a straightforward end to a life defined by fanaticism, delusion, and contradiction.

But the simplicity of the report belied the complexity of the man and the 46 years he had spent in Allied custody. In the meticulously controlled

Did The Nazis Develop Nuclear Weapons? – Mythbusting Berlin

The Nazi obsession with super-weapons became so serious in the closing stages of the Second World that Adolf Hitler personally believed that such ‘Wunderwaffen’ both existed in a usable form – and would save the country from defeat. Had the Nazis managed to develop nuclear weapons by 1945 – the outcome of the war would surely have been different. But how close were Hitler, Himmler, and his henchmen to developing an A-bomb?

Did The Nazis Invent Decaf Coffee? – Mythbusting Berlin

Persistent rumors claim that Nazis preferred their coffee anything but pure, leading some to wonder if they might have influenced the development of decaffeinated coffee. Although decaf was already widely available across Europe by the mid-20th century, speculation continues: could the Nazis really have played a role in popularizing—or even discovering—this caffeine-free alternative, or is this simply another caffeinated conspiracy cooked up to sensationalize an ordinary historical detail?

Did The Nazis Invent The Bicycle Reflector? – Mythbusting Berlin

The fruits of wartime ingenuity are plenty – so many, in-fact, that it has become somewhat of a worn cliche that as the guns start firing the innovators get to work, often solving problems while providing more problems for the enemy to overcome.The kind of progress that results in the production of newer improved, more lethal weapons, such as to increase the chances of victory.

Did The Nazis Run The Largest Counterfeiting Operation In History? – Mythbusting Berlin

During the Second World War the Nazis masterminded an astonishing plot to destabilise Britain by flooding its economy with counterfeit banknotes. Crafted in secret by concentration camp prisoners, this forged fortune became the most ambitious counterfeiting operation ever attempted. But was it history’s largest? Dive into the extraordinary tale of Operation Bernhard,

rife with deception, survival, and intrigue—revealing the truth behind one of the Third Reich’s most audacious schemes and its surprising legacy.

Did The Second World War End In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

When is a war ever truly over? When the last shot is fired in anger would seem like the best measure. Rarely, though, is it possible to gain insight into such a moment.

Remarkably, a record still exists of such a moment at the end of the First World War on the Western Front. A seismic register and recording of the last belching battery of British guns firing artillery across no-man’s-land, followed by a profound

Did The Spanish Flu Pandemic Help The Nazis Take Power? – Mythbusting Berlin

The devastating Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918-1919 struck amid Germany’s post-war turmoil, compounding social instability, economic hardship, and widespread political disillusionment. Could this catastrophic health crisis have indirectly paved the way for Nazi ascension? While often overshadowed by war and revolution, the pandemic’s profound psychological and societal impacts arguably contributed to the perfect storm, enabling extremist ideologies—including Nazism—to gain popularity and ultimately seize power in a fractured Germany.

Have Adolf Hitler’s Remains Been DNA Tested? – Mythbusting Berlin

In the smouldering ruins of Berlin in 1945, the world’s most wanted man vanished. Did Adolf Hitler, as official history attests, die by his own hand in the Führerbunker? Or did he escape, fuelling a thousand conspiracy theories that have echoed for decades? For years, the Soviets claimed to hold the gruesome proof of his death: a skull fragment and a set of teeth, locked away in Moscow archives. But in an age of definitive

How Did The Nazi Concentration Camps Differ From The Soviet GULAG?

The Nazi concentration camps and Soviet Gulag system have often been conflated in popular imagination—twin symbols of twentieth-century totalitarian horror. Yet the two systems operated on fundamentally different principles. One extracted labor to fuel industrialisation while accepting mass death as collateral damage; the other evolved into purpose-built machinery of genocide. Understanding these distinctions isn’t merely academic—it reveals how different ideologies produce different atrocities, and why Germany and Russia reckon with these legacies so differently today.

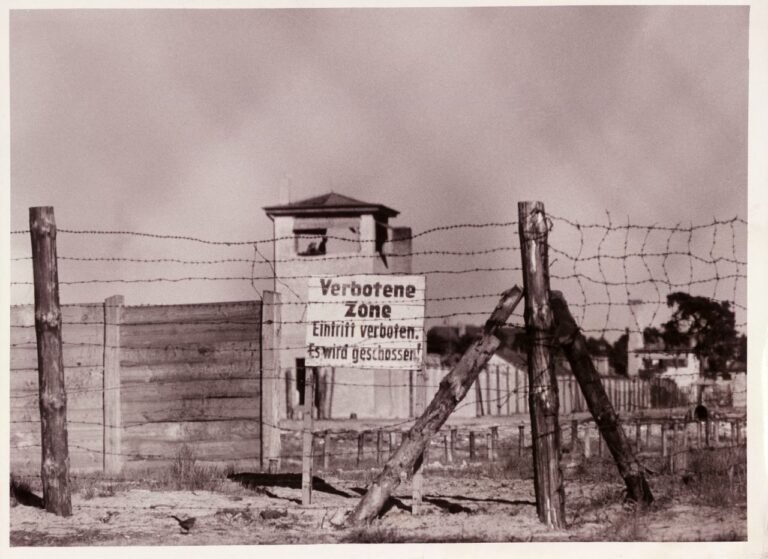

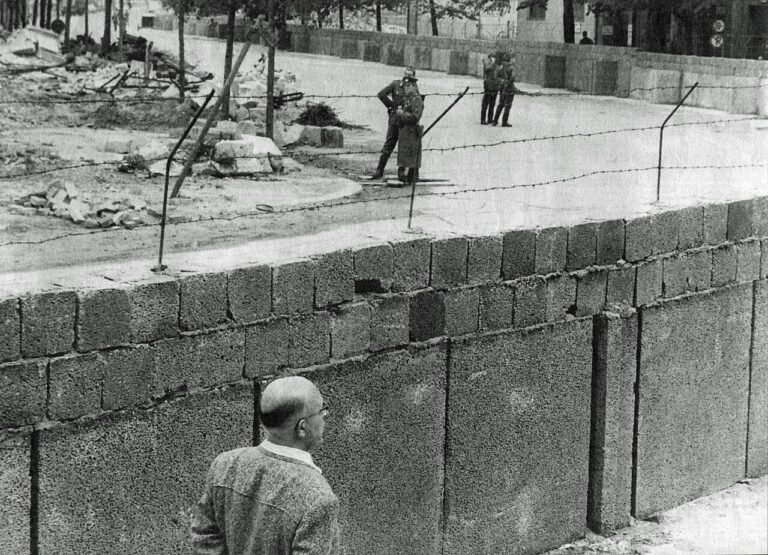

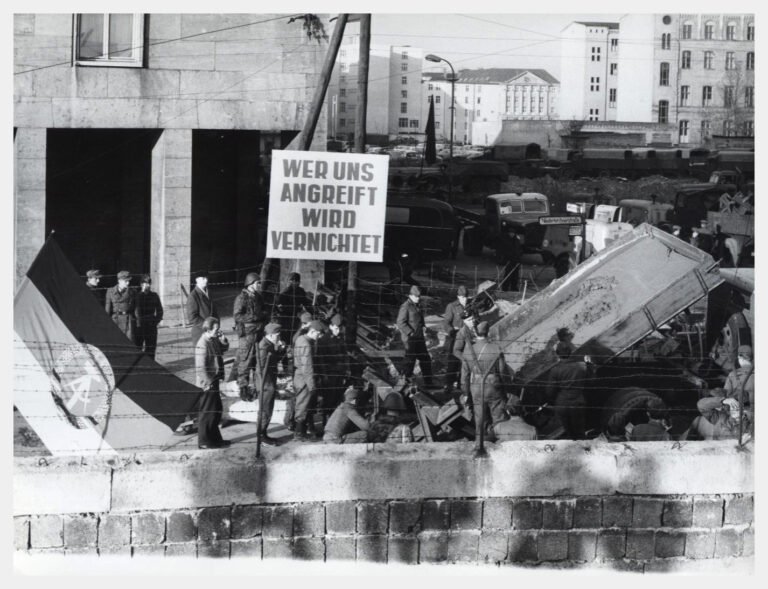

How Long Did It Take To Build The Berlin Wall? – Mythbusting Berlin

It is one of the most enduring images of the 20th century: a city divided overnight. The popular narrative tells us that Berliners went to sleep in a unified city and woke up in a prison. While the shock of August 13th 1961, was very real, the idea that the ‘Wall’ appeared instantly is a historical illusion. The physical scar that bisected Berlin was not a static creation, but a living, malevolent beast that evolved

How Many Assassination Attempts On Adolf Hitler Were There? – Mythbusting Berlin

Nazi leader, Adolf Hitler, projected an aura of invincibility, a man of destiny shielded by providence. But behind the carefully constructed image of the untouchable Führer lies a story of constant threat, of bombs that failed to detonate, and errant bullets that missed their mark. Unearth the hidden history of the numerous attempts on Hitler’s life as we explore the courage of those who tried to change the course of history and the devil’s luck

How Many Jews Died In The Holocaust? – Mythbusting Berlin

The answer to the question posed of how many Jews died in the Holocaust is a simple one: too many. That merely one death was an unforgivable obscenity is a fundamental and necessary realisation in understanding the capriciousness of this unparalleled racial genocide. To comprehend, however, the full number of Jews murdered in Europe by the Nazi regime in the 1930s and 1940s is a detective story of epic proportions: the evidence overwhelming, multifaceted, and

How Many People Died Trying To Escape East Germany? – Mythbusting Berlin

The image of the Berlin Wall is seared into our collective memory, a concrete symbol of Cold War oppression. We think of the daring escapes and the tragic deaths of those who failed. But that well-known number is only a fraction of the truth. The story of those who died trying to escape East Germany is far broader and more complex than most imagine, stretching along a thousand-kilometer border and out into the cold waters

How Old Is Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

A relatively new arrival in Europe, Berlin is over 1000 years younger than London, nevermind Rome or Athens, Jerusalem or Jericho. Just how old is Berlin though?

A question fraught with false assumptions and distortions – that has more often than not been answered with propaganda as it has with the cold hard truth.

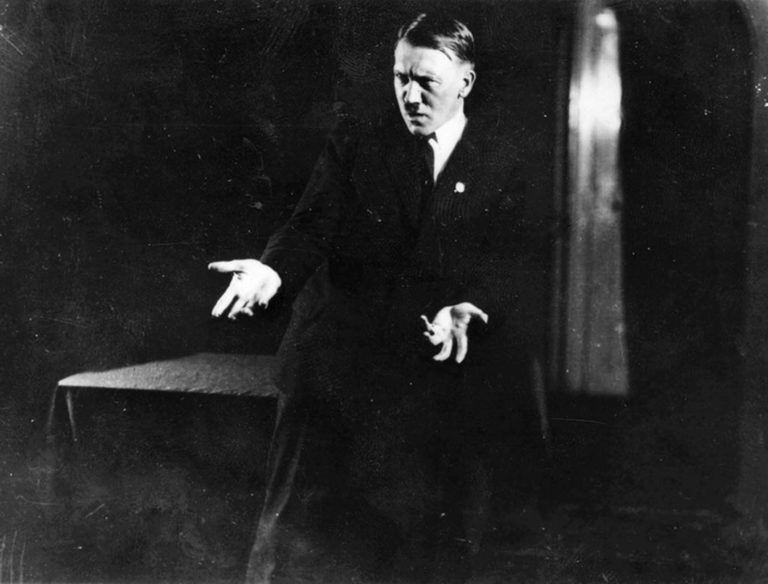

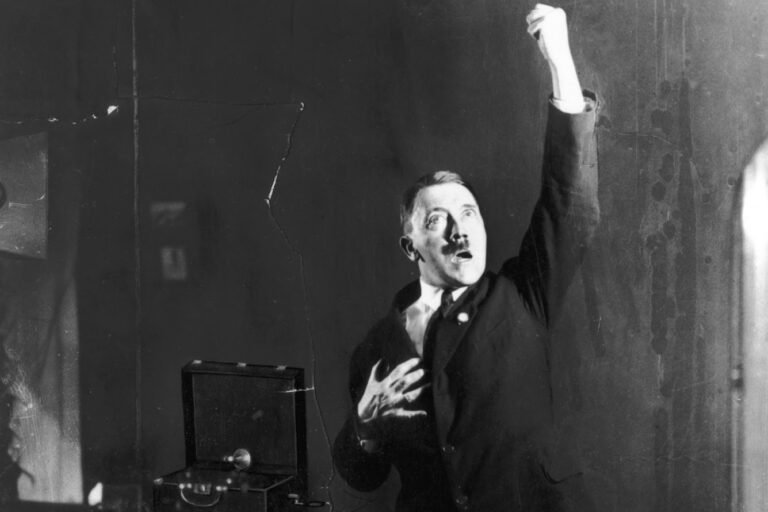

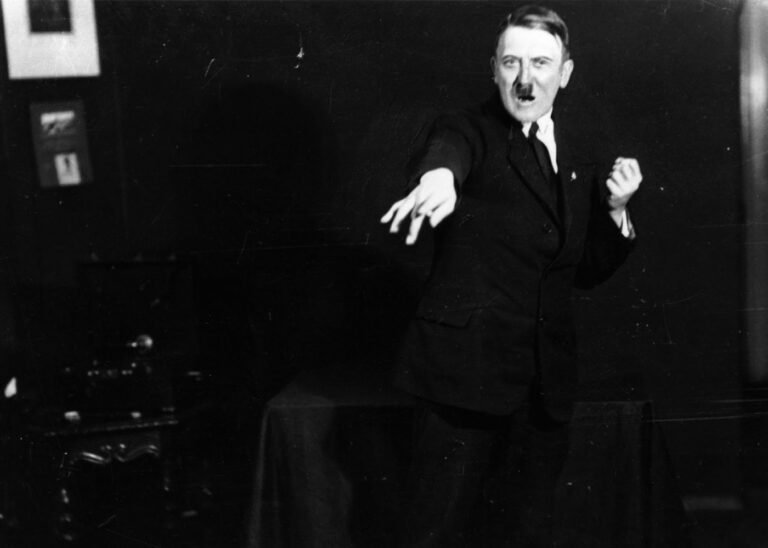

Was Adolf Hitler A Drug Addict? – Mythbusting Berlin

Solving the enigma of the ‘Führer’ has become a preoccupation for many, since the arrival of the Austrian-German onto the world stage – although moving beyond the mythology without falling into the trap of prejudically extrapolating on the psychopathography of Hitler or demonising so as to excuse his actions has proven problematic. What to make of the man who became more than the sum of his masks? The painter; the military dilettante, the mass murderer,

Was Adolf Hitler A Freemason? – Mythbusting Berlin

History abhors a vacuum, but adores a mystery. Such is the speculative fiction suggesting a secret allegiance behind the rise of the Third Reich – that the catastrophe of the Second World War was orchestrated from the shadows of a Masonic lodge. The image of Adolf Hitler—the drifter from Vienna turned dictator—as a covert initiate of the very brotherhood he publicly reviled, however, creates a paradox that collapses under scrutiny. As when we unlock the

Was Adolf Hitler Gay? – Mythbusting Berlin

In the shadowy corridors of Third Reich history, few questions provoke as much tabloid curiosity and scholarly exasperation as the sexuality of Adolf Hitler. For decades, rumors have swirled—whispered by political enemies in 1930s Munich, psychoanalyzed by American spies in the 1940s, and sensationalized by revisionist authors today. Was the dictator who condemned thousands of men to concentration camps for “deviant” behavior hiding a secret of his own? By peeling back the layers of propaganda,

Was Adolf Hitler Jewish? – Mythbusting Berlin

Was the dictator who orchestrated the murder of millions of European Jews secretly one of them? It is perhaps the darkest irony imaginable, a story whispered for decades in backrooms, bars, and conspiracy forums alike. The most-common rumour – the ‘Frankenberger Myth’ – suggests that Adolf Hitler’s paternal grandfather was Jewish, a secret so damaging it could have unraveled the entire Nazi regime. But where does this claim come from? And, more importantly, is there

Was Currywurst Invented In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

Explore the story behind what many consider Berlin’s most iconic snack—the ever-so-humble Currywurst. Often hailed as an enduring symbol of culinary creativity amid Cold War scarcity, this humble dish has inspired fierce debate about its true origin. But was it genuinely invented here in Berlin, or have proud locals simply adopted and elevated this spicy street-food favorite into legendary status all their own?

Was Fanta Invented By The Nazis? – Mythbusting Berlin

As one of the most secretive organisations in the world, the Coca Cola corporation refuses to share its secret recipe with anyone. Famously insisting only on shipping the base syrup of its drinks to plants around the world to be carbonated and distributed.

This combined with the trade limitations of the Second World War may have led to the introduction of one of the most popular soft-drinks in the world. But could it be true:

Was Frederick The Great Gay? – Mythbusting Berlin

Frederick II of Prussia, better known as Frederick the Great, is often remembered as the archetypal enlightened monarch – a brilliant military commander, patron of the arts, and learned philosopher. Yet behind the stern portraits of this 18th-century warrior-king lies a personal life long shrouded in intrigue and speculation. Intrigue around the king’s sexual orientation has persisted through the centuries, chiefly revolving around one question: Was Frederick the Great gay?

Was Henry Ford A Nazi? – Mythbusting Berlin

US auto tycoon, Henry Ford, holds the ignominious distinction of being the only American Adolf Hitler praised by name in his National Socialist manifesto: ‘Mein Kampf’. This was not, as it turns out, the only connection between Ford and the Party of Hitler, Himmler, and the Holocaust.

Ford’s overt affinity with the Third Reich reveals a troubling past. How deep these connections ran, and how consequential they were for both sides, is a chapter

Was The Colour Blue Invented In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

Tracing the true history of blue—from ancient Egyptian dyes to the accidental discovery of Prussian Blue in a Berlin lab. We’ll debunk myths about seeing blue, explore colonial indigo plantations, scale mountains with a cyanometer, and trace Van Gogh’s starry skies—all to answer one question: how did Berlin shape our understanding of the world’s rarest color?

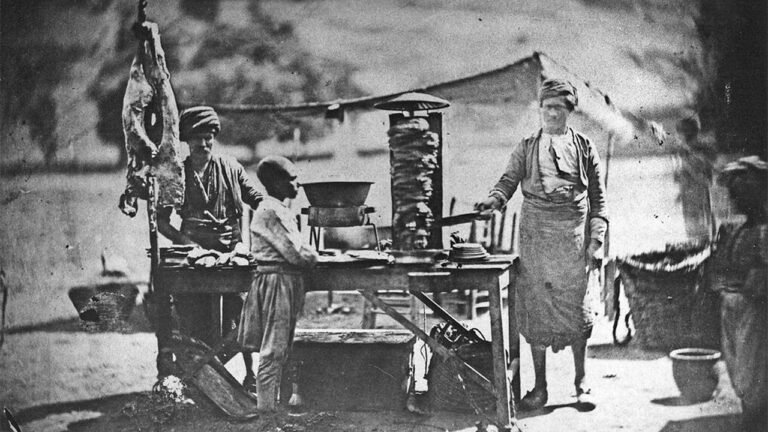

Was The Döner Kebab Invented In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

Unlikely icon of immigrant success; fast food symbol of the working class; over-hyped midnight disco eat; or culturally appropriated cuisine? Its influence goes far beyond layers of seasoned meat and fresh vegetables stuffed into pita bread. But does Berlin deserve credit as the Döner Kebab’s true birthplace, or has the city merely refined and popularized a culinary tradition imported from elsewhere?

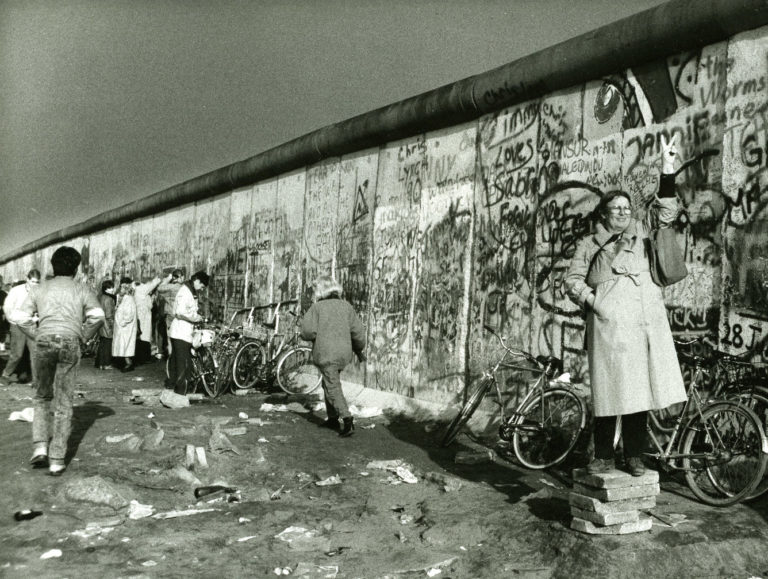

Was The Fall Of The Berlin Wall An Accident? – Mythbusting Berlin

On a seasonally crisp night in November 1989, one of the most astonishing events of the 20th century occurred. After twenty eight years, three months, and twenty eight days of defining and dividing the German capital, the Berlin Wall ceased to exist – at least in an abstract sense. Although the removal of this symbol of the failure of the East German system would take some time, its purpose – as a border fortification erected

Was The Nazi Party Democratically Elected? – Mythbusting Berlin

The myth persists that Adolf Hitler rose to power through popular democratic choice. Yet history reveals a darker, more complicated truth. Hitler’s ascent involved exploiting democratic institutions, orchestrating violence, propaganda, and political intrigue—not a simple election victory. Understanding how Germany’s democracy collapsed into dictatorship helps illuminate the dangerous interplay between public desperation, elite miscalculations, and extremist ambition, providing crucial lessons for safeguarding democracy today.

Were The Allied Bombings Of Germany War Crimes? – Mythbusting Berlin

The history of the Allied bombing of Germany during the Second World War still triggers fierce debate. Was reducing cities to rubble a necessary evil – justice from above in a just war – or an unforgivable crime? Can the intentional targeting of civilians ever be justified as militarily necessary?

In a conflict where all rules seemed to vanish, an even more pertinent question persists: by the very standards they would use to judge their

Were The Nazi Medical Experiments Useful? – Mythbusting Berlin

Before the Nazi period, German medicine was considered the envy of the world – a shining monument to progress. But deep within that monument, a rot was spreading, one which would collapse the entire structure into an abattoir. From the wreckage, we are left with a profoundly uncomfortable inheritance: a moral enigma wrapped in doctor’s whites.

What to make of the data, the images, and the terrible knowledge gleaned from unimaginable human suffering. Whether

What Are The Origins Of The Nazi Salute? – Mythbusting Berlin

A specter is haunting the modern mind, a gesture so charged with the dark electricity of history that its mere depiction can unleash a storm of controversy.

It is a simple movement: the right arm, stiff and straight, raised to the sky. But in that simplicity lies a terrifying power, a symbol of a regime that plunged the world into an abyss and a chilling reminder of humanity’s capacity for organised hatred.

This

What Are The Origins Of The Nazi Swastika? – Mythbusting Berlin

Long before the legions of the Third Reich marched beneath its stark, unnerving geometry, the swastika lived a thousand different lives. It was a symbol of breathtaking antiquity, a globetrotting emblem of hope and good fortune that found a home in the most disparate of cultures. To even begin to understand its dark 20th-century incarnation, one must first journey back, not centuries, but millennia.

What Are The Pink Pipes In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

A first-time visitor to Berlin could be forgiven for thinking the city is in the midst of a bizarre art installation. Bright pink pipes, thick as an elephant’s leg, climb out of the ground, snake over pavements, arch across roads, and disappear back into the earth. Are they part of a complex gas network? A postmodern artistic statement? A whimsical navigation system? These theories, all logical, are all wrong. The truth is far more elemental,

What Do The Colours Of The German Flag Symbolise? – Mythbusting Berlin

What does a flag mean? Is it merely a coloured cloth, or does it hold the hopes, struggles, and identity of a nation? The German flag, with its bold stripes of black, red, and gold, is instantly recognisable. But the story of its colours is a tumultuous journey through revolution, suppression, and reinvention. The common explanation for their symbolism is a simple, romantic verse, yet the truth is a far more complex and contested tale,

What Happened To Adolf Hitler’s Alligator? – Mythbusting Berlin

It is often said that you can tell a lot about a person by their relationship with animals; that owners often come to look and behave like their pets. Or is it perhaps more that people choose their pets to correspond to their personality? Nazi leader Adolf Hitler’s love of dogs, for example, is well documented but what is there to make of his relationship with reptiles?

What Happenened To The German Royal Family? – Mythbusting Berlin

When the smoke cleared over the trenches in November 1918, the German Empire had evaporated, and with it, the divine right of the Hohenzollern dynasty. Conventional wisdom suggests the family simply vanished into the sepia-toned obscurity of history books—exiled, forgotten, and irrelevant. But dynasties, like weeds in a landscaped garden, are notoriously difficult to uproot entirely. The story of the German royals did not end with the Kaiser’s flight to Holland; it merely shifted gears.

What Is The Difference Between Fascism & Nazism? – Mythbusting Berlin

While the terms ‘Fascist’ and ‘Nazi’ are often bandied around interchangeably as shorthand for tyranny – Italian fascism and German National Socialism were distinctly different beasts. Albeit ideological kin. One an ideology of state-worship, born from post-war chaos and national pride; the other built upon a fanatical, pseudo-scientific obsession with race. Two peas in the same totalitarian pod – twins in tyranny – more succinctly summarised as the Nazi chicken to the Fascist egg.

What Was Checkpoint Charlie? – Mythbusting Berlin

Checkpoint Charlie remains among Berlin’s most visited historical sites, famed worldwide for its significance during the Cold War. Originally established as a modest border-crossing point, it evolved dramatically over the decades into an international symbol of freedom, espionage, and intrigue. Today, critics and locals often dismiss it as little more than a tourist trap—Berlin’s Disneyland—but how exactly did Checkpoint Charlie get its peculiar name, and what truths hide behind its popularity?

What Was Prussia? – Mythbusting Berlin

Prussia’s legacy is both remarkable and contentious—once a minor duchy, it rose dramatically to shape modern European history. Renowned for military discipline, administrative efficiency, and cultural sophistication, Prussia was instrumental in uniting the German states, laying foundations for a unified Germany. But how did this kingdom, with its roots in Baltic territories, achieve such prominence, and why does its complex history continue to evoke admiration, debate, and occasional discomfort in Germany today?

What Was The Berlin Airlift? – Mythbusting Berlin

In the ruins of 1948, the silence of Berlin was not a sign of peace, but a held breath before a new catastrophe. The city, drowning in rubble and political intrigue, became the staging ground for the twentieth century’s most audacious gamble. While popular history remembers the chocolate parachutes and smiling pilots, the reality of the Berlin Airlift was a terrifying operational nightmare born from a ruthless currency war. It wasn’t just a humanitarian mission;

What Was The Socialist Kiss? – Mythbusting Berlin

It is one of the most curious and enduring images of the Cold War: two middle-aged, grey-suited men, locked in a fervent embrace, their lips pressed together in a kiss of apparent revolutionary passion. This was the ‘Socialist Fraternal Kiss’, a ritual that, for a time, seemed to encapsulate the unwavering solidarity of the Eastern Bloc.

But what was behind this seemingly intimate gesture? Was it a genuine expression of camaraderie, a piece of

Who Built The Berlin Wall? – Mythbusting Berlin

One of the most common questions I have encountered from people curious about Berlin, and often so cryptically phrased. Who built the Berlin Wall? A simple five-word query, yet one that can be read one of two ways. More than thirty years since the ‘Fall of the Wall’, the story of its construction continues to baffle many who are mainly familiar with its existence through knowledge of its importance…

Who Really Raised The Soviet Flag On The Reichstag? – Mythbusting Berlin

One iconic photograph has come to symbolise the Red Army’s victory over Nazi Germany in 1945—the Soviet flag waving triumphantly above Berlin’s battered Reichstag building. Yet behind this enduring image lies controversy, confusion, and political manipulation. Who truly raised the Soviet banner atop the Reichstag? Was it a spontaneous act of heroism or carefully staged Soviet propaganda? Decades later, unraveling the truth reveals surprising layers beneath the mythologized symbol of Soviet triumph.

Who Was Really Responsible For The Reichstag Fire? – Mythbusting Berlin

Various theories have been posited as to who actually set fire to the German parliament in 1933. Was it the opening act in an attempted Communist coup or a calculated false flag operation carried out by elements of the Nazi Party, intended to create the conditions necessary for introducing single-party rule? And what part did the young man from Holland, arrested shirtless inside the building the night of the fire, play in this event?

Who Were The Last Nazis On Trial? – Mythbusting Berlin

More than eighty years after the Holocaust, courtrooms across Germany still echo with testimony from the final chapter of Nazi justice. Centenarian defendants in wheelchairs, their faces hidden behind folders, arrive to answer for crimes committed in their youth. These are not the architects of genocide—those men faced their reckoning at Nuremberg decades ago. These are the guards, the secretaries, the bookkeepers: ordinary people who enabled extraordinary evil. Their trials represent a legal revolution: the

Why Is Berlin The Capital Of Germany? – Mythbusting Berlin

There was little in its humble origins—as a twin trading outpost on a minor European river—to suggest that Berlin was destined for greatness. It sits on the flat expanse of the North European Plain, a landscape once dismissively referred to as the “sandbox of the Holy Roman Empire.” Unlike other world capitals, it lacks breathtaking scenery or a naturally defensible position. It is a city built not on majestic hills or a grand harbour, but