“Some cursed fraud

Of enemy hath beguiled thee, yet unknown,

And me with thee hath ruined”

John Milton, Paradise Lost

Economic warfare has long been a critical tool in statecraft, used to weaken adversaries by disrupting their financial stability.

Among the many tactics employed, currency counterfeiting en-masse stands out as a particularly insidious method of undermining an enemy’s economy. By flooding a rival nation’s market with fake money, states can trigger inflation, erode trust in the currency, and destabilise financial institutions.

In the words of the renowned economist John Maynard Keynes, “The best way to destroy the capitalist system is to debauch the currency.”

The impact of currency counterfeiting as a tool of economic warfare extends beyond immediate financial losses, striking at the psychological and structural foundations of a society.

When a nation’s currency is perceived as vulnerable to forgery by hostile forces, it risks devaluation, capital flight, and a loss of international confidence, all of which can lead to economic decline.

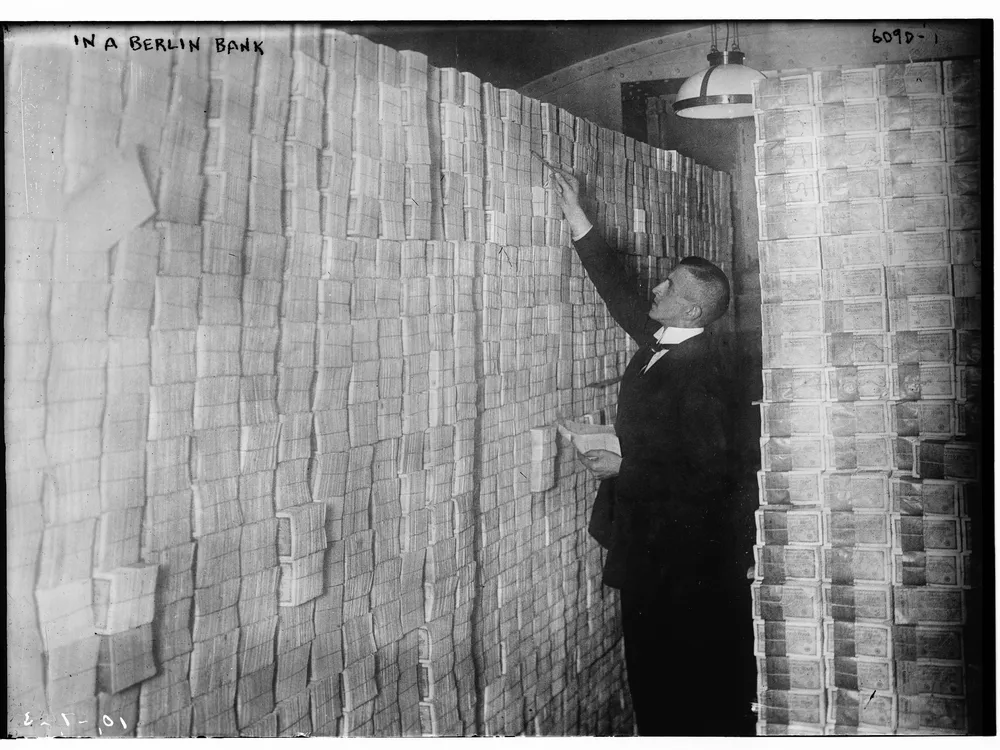

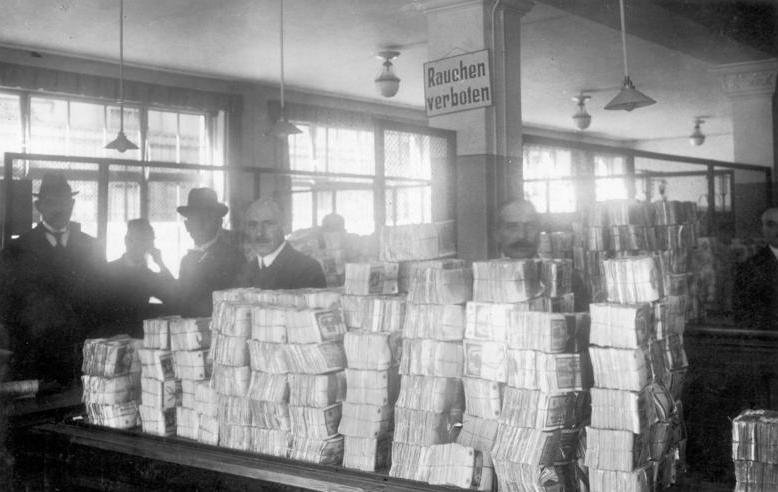

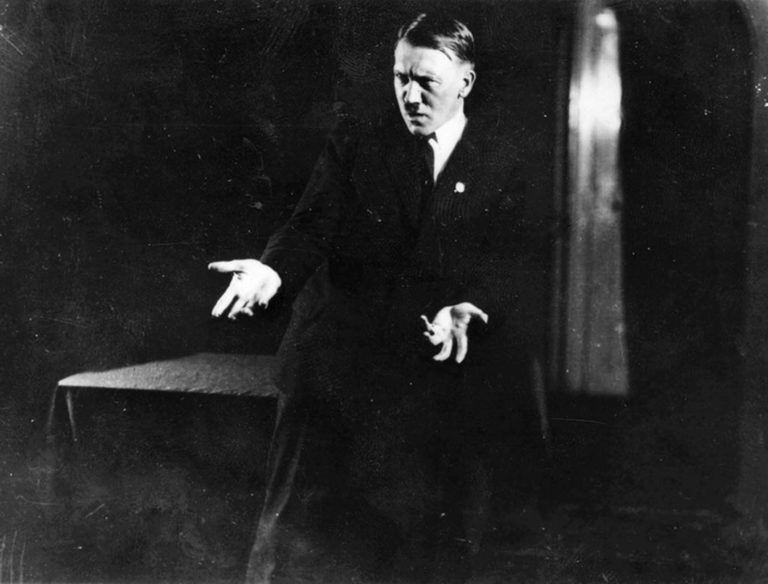

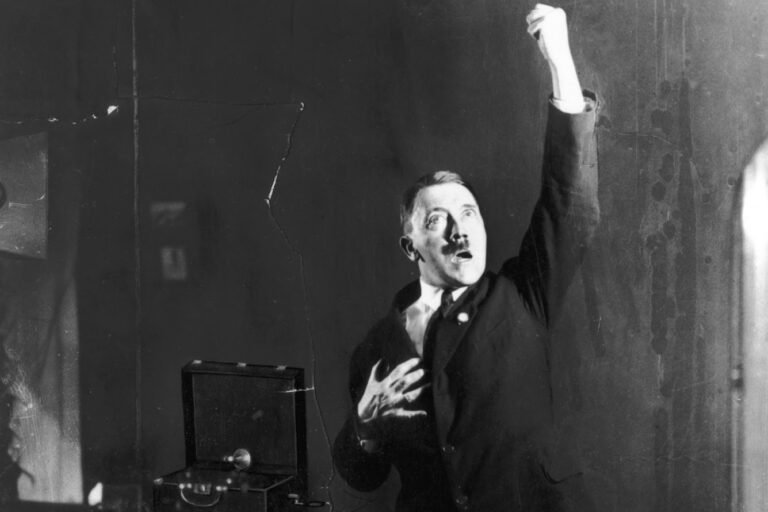

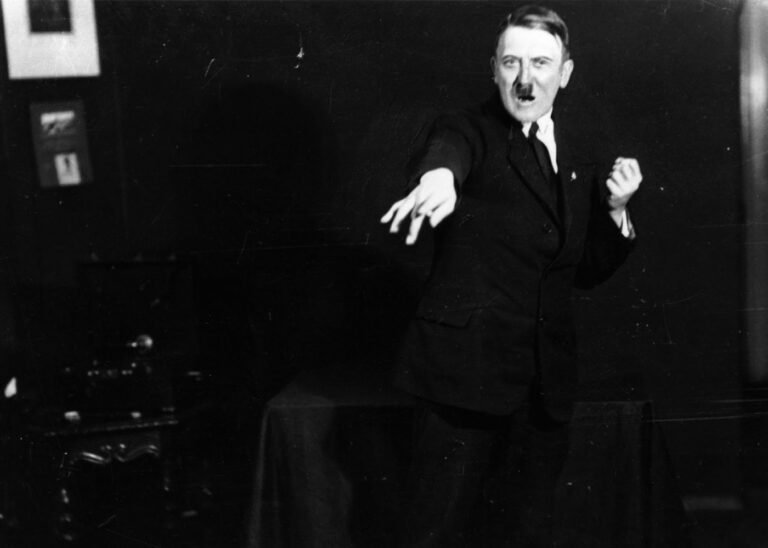

For the people of pre-war Germany of the 1920s and 30s, the real world consequences of economic turmoil were self-evident. For that matter, it could be said that the helplessness felt in the whirlwind of the financial disasters that became the German economy was one of the most common shared experiences – rich and poor, gentile and jew, were affected alike.

The sense that these economic woes of the 20s and 30s had in large part been inflicted on the people of the country by external – and as prominently featured in Nazi propaganda – internal actors was a widespread belief.

That such a thing could be weaponized and wrought on the economies of enemy powers could only be considered a natural realisation of sorts.

So it was, that during the early years of the Second World War, as Hitler’s armies swept across Europe, a secret operation to destabilise the Allied powers was concocted and begun.

If Germany could be brought to its knees through economic manipulation and the derailing of its industry, so too could the enemies of the Reich.

–

The Deceptive Art of Counterfeiting

“To be clever enough to get all that money, one must be stupid enough to want it”

G. K. Chesterton, The Paradise of Thieves

Counterfeiting is often called the world’s ‘second-oldest profession,’ and for good reason.

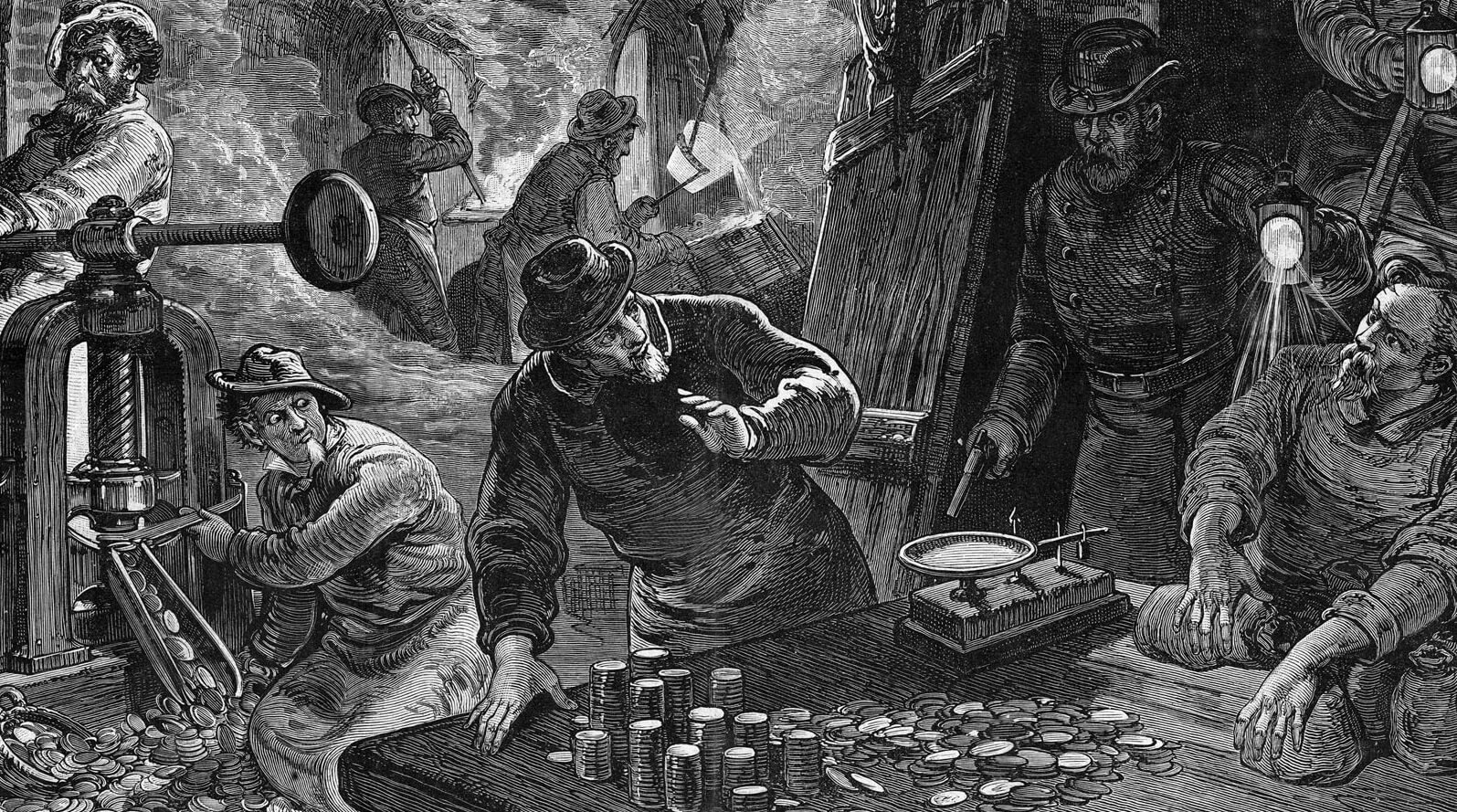

In the beginning, there were coins.

The first recorded instance of counterfeit currency can be traced all the way back to ancient Greece, where fraudulent coins were made using an alloy of silver and base metals like copper. Although this practice was considered a serious offence, punishable by death, the allure of easy profits remained irresistible to many.

Wherever money has existed, there have been those tempted to create their own bogus version of it.

Fast forward to the Middle Ages, when the art of counterfeiting underwent a transformation, giving rise to the term ‘coin clipping’ – involving shaving small amounts of precious metal from the edges of coins and melting the shavings to create new, albeit illegitimate, currency.

Coin clipping became so widespread in England that the authorities were compelled to take action. In 1279, King Edward I ordered a recoinage, introducing a new design with a grooved edge to deter counterfeiters. A practice that continues to the present day with many coins still issued around the world.

The quote, “an unclipped penny is the sign of a well-governed realm” became a popular refrain.

With the introduction of paper money in the late 17th century, new avenues opened up for fraudsters. Early counterfeiters, or ‘coiners’ as they were known in Britain, used primitive printing methods and made no attempt to replicate the intricate details found on genuine banknotes. Despite this, their crude efforts were often successful, as the public was not yet accustomed to the novel concept of paper currency.

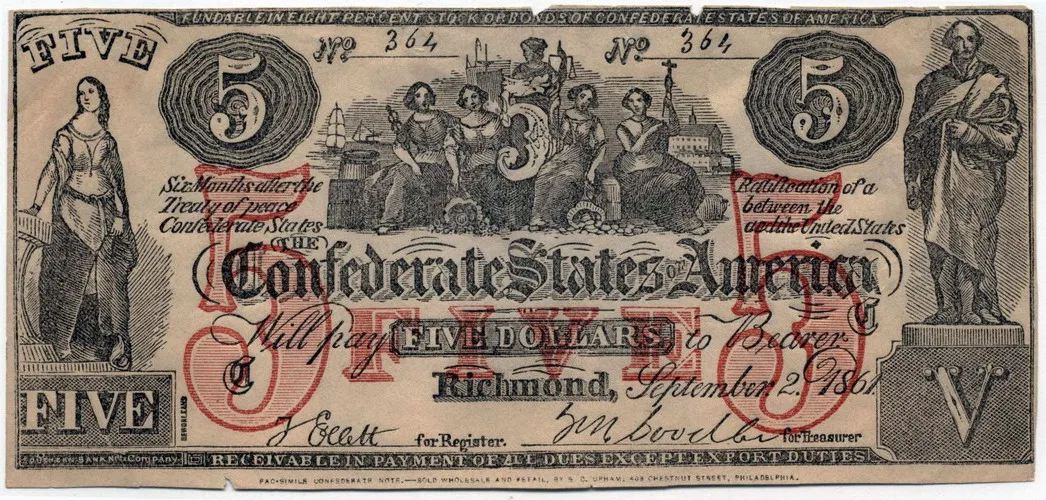

The 18th century witnessed a surge in counterfeiting, particularly in Britain and the American colonies, which experienced rapid economic growth. In the United States, the Revolutionary War was the catalyst for an unprecedented boom in counterfeiting. British spies, intent on undermining the fledgeling American economy, flooded the market with fake ‘Continental currency’.

George Washington himself lamented, “I am wearied to death with the miserable state of our currency,” as the value of genuine banknotes plummeted.

The British at time had devised a scheme to print and distribute fake Continental currency in the rebellious colonies. This “unspeakable” tactic was condemned by patriot writers like Thomas Paine, who lambasted the British commander for stooping to such trickery – no general before had been “mean enough even to think of it,” Paine railed. Yet the scheme worked: by 1781 the flood of forged paper dollars helped render the young United States’ currency almost worthless. One American politician, John Langdon, exclaimed that a single skilled counterfeiter “has done more damage than 10,000 men could have done” on the battlefield. The phrase “not worth a Continental” was born from this financial sabotage.

In-fact, no strangers to the dark arts of counterfeiting, the British Crown had allegedly churned out forged French assignats (revolutionary paper money) by the wagonload in the 1790s, aiming to wreck the economy of republican France.

A century later, during the U.S. Civil War, rumors abounded that the Union printed fake Confederate notes and snuck them southward to undermine the Confederacy’s shaky currency. War has a way of turning banknotes into another kind of ordnance.

While the British played a major part in the spread of fake currency in the 18th and 19th century, the fight against forgeries was also a major focus for the workers of the Royal Mint.

In the late 17th century, none other than Sir Isaac Newton – better known for discovering gravity – took it upon himself to hunt down and prosecute coin counterfeiters in London. As Warden of the Royal Mint, Newton frequented taverns in disguise, tracked gangs of forgers, and even gathered evidence in secret, showing a detective’s zeal. He reportedly had several notorious coiners hanged for high treason. If “the criminal is the creative artist; the detective only the critic,” as author G.K. Chesterton quipped, then Newton proved a formidable critic indeed. Thanks to his efforts, Britain’s coinage was reformed and secured. But even Newton, with all his brilliance, could not end the counterfeiter’s craft for good.

In response to the seemingly inextinguishable threat of mass currency manipulation, governments and central banks invested heavily in anti-counterfeiting measures, adopting a range of innovative security features. These included watermarks, security threads, and intricate patterns known as ‘guilloché’.

The global economic turmoil of the 1920s and 1930s provided fertile ground for counterfeiters, who took advantage of the widespread fear and uncertainty to ply their trade. The Great Depression saw a marked increase in the circulation of fake currency, with desperate citizens often turning a blind eye to the dubious provenance of the banknotes they received.

Still, experts often assumed that major currencies – especially those of great powers – were practically impossible to imitate perfectly.

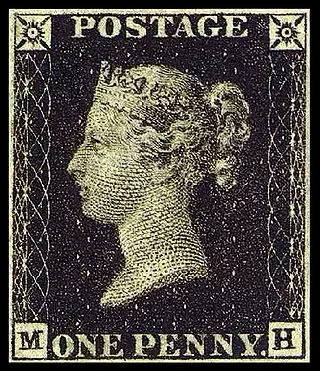

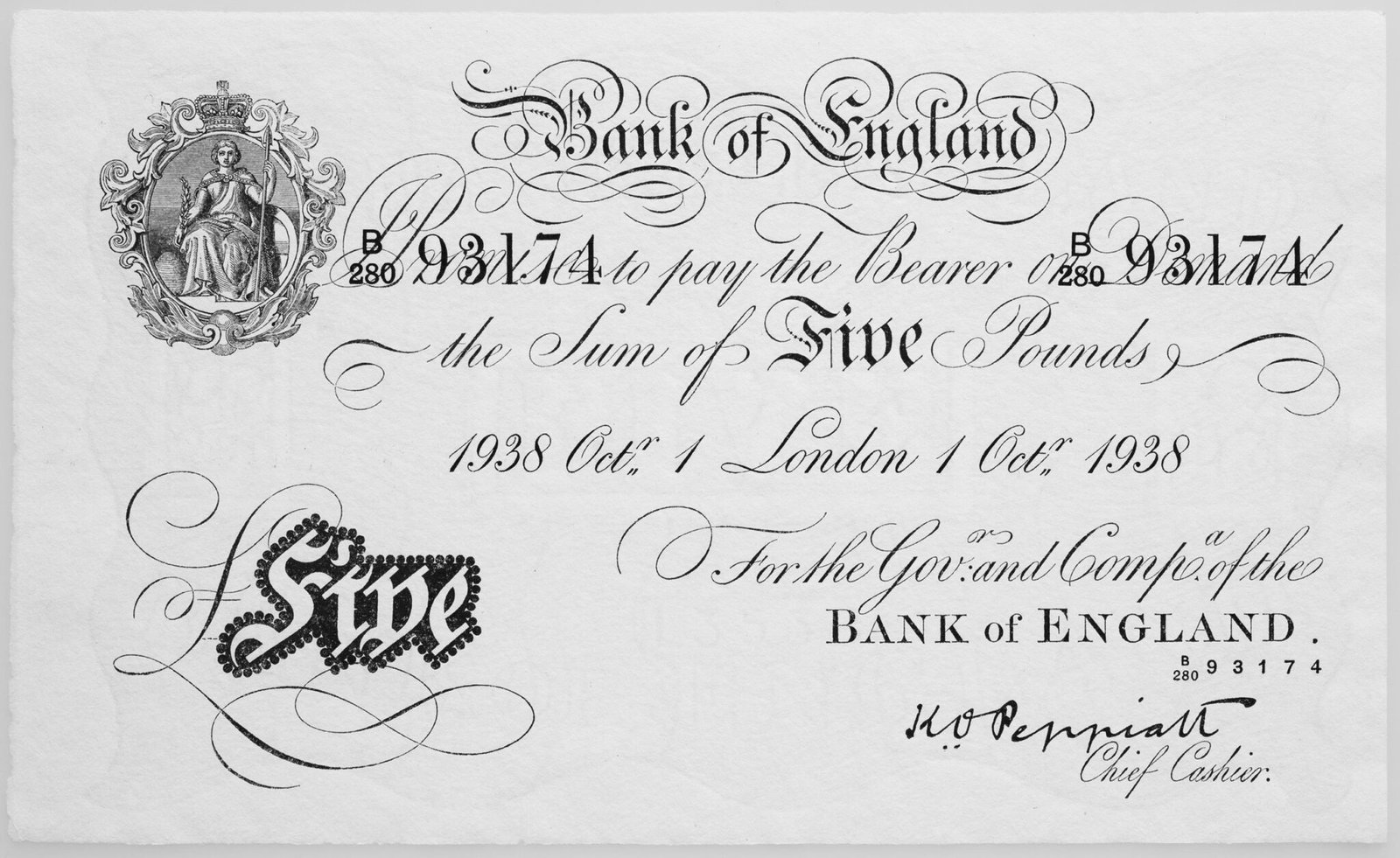

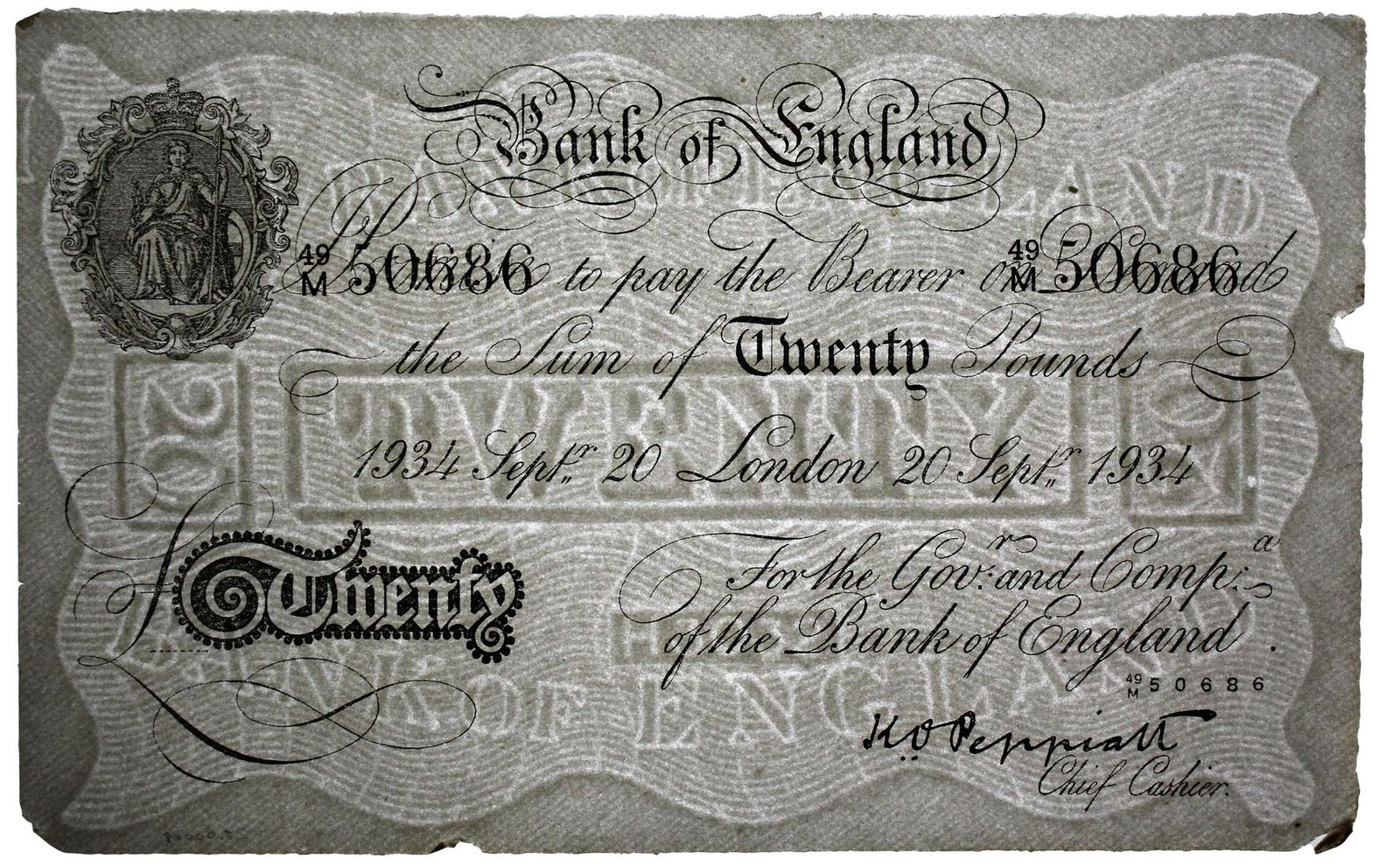

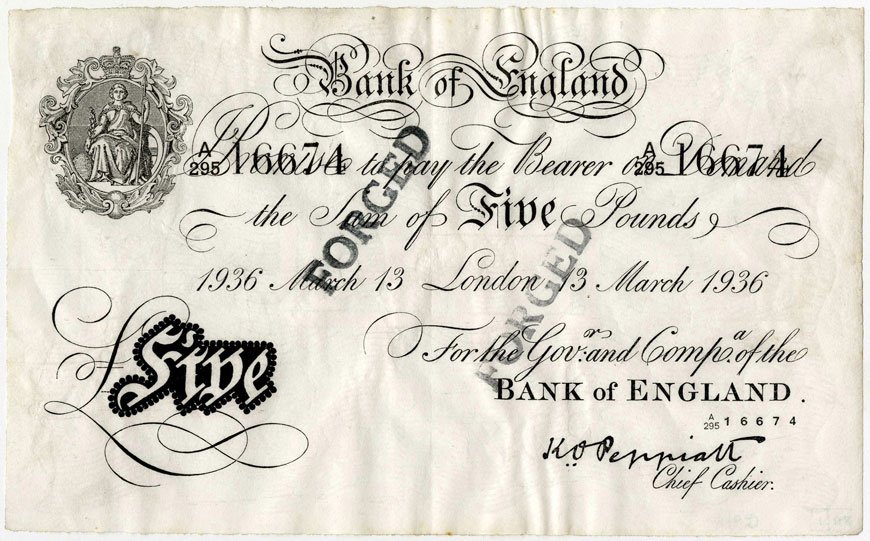

On the eve of the Second World War, British banknotes, in particular, had a reputation as the gold standard (literally and figuratively) of secure currency. After all, no one had ever successfully duplicated the Bank of England’s elegant ‘white notes’ on a large scale.

But as we shall see, that complacency would be shattered by an audacious plot born in Nazi Germany.

–

Operation Andreas

“Heydrich had an incredibly acute perception of the moral, human, professional and political weaknesses of others. His unusual intellect was matched by the ever-watchful instincts of a predatory animal. He was inordinately ambitious. It seemed as if, in a pack of ferocious wolves, he must always prove himself the strongest and assume the leadership.”

Walter Schellenberg, SD head of foreign intelligence for Nazi Germany

The outbreak of the Second World War in 1939 gave Nazi leaders a chance to turn currency counterfeiting into a strategic weapon.

Just weeks after Nazi Germany invaded Poland, a secret meeting was held in Berlin. On September 18th 1939, Arthur Nebe – chief of the Reich Criminal Police – proposed an audacious plan: to use master forgers to produce huge quantities of fake British banknotes.

By raining forged pounds over the United Kingdom or injecting them into the Allied economy, the Nazis hoped to trigger hyperinflation, collapsing Britain’s financial system from within. Nebe’s boss, SS General Reinhard Heydrich, found the idea intriguing and secured approval from the highest authority.

Not everyone in the Nazi hierarchy was thrilled. Economics Minister Walther Funk worried that weaponizing counterfeit money might violate international law. Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels privately called it “ein grotesker Plan” – a grotesque plan – though he conceded it could be effective if executed well.

Officially the plan would be titled, ‘Offensive against Sterling and Destruction of its Position as World Currency’. The counterfeiting operation, however, was given a seemingly bland code name – Unternehmen Andreas (Operation Andreas) – rumoured to be due to the British flag bearing the Cross of St. Andrew. A the Germans thought that it looked like an ‘X’ striking through the flag, so Operation Andreas would strike through the value of the pound, thus making it worthless.

Commanded by SS Major Alfred Naujocks, Operation Andreas was given an extensive budget of 2 million Reichsmarks.

A crack counterfeiting unit was established in Berlin, consisting of technicians, printers, and criminal experts in forgery. Jewish prisoners from concentration camps would also be forced to participate. Naujocks himself was already well-known for his role in clandestine operations, as he had helped fake a Polish attack on a German radio station in Gleiwitz – the pretense for the start of the Second World War.

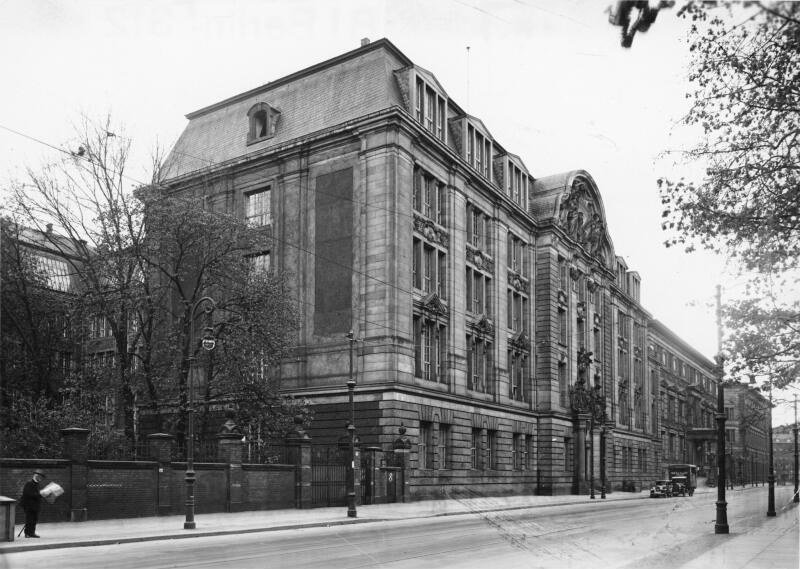

The headquarters for the operation was a villa in the Berlin Charlottenburg district run by the Reichssicherheitshauptamt (RSHA – Amt VI) – specifically, Delbruckstrasse 6A. Dubbed ‘The Devil’s Workshop’ for all the secret espionage documents created there. The second floor contained the photographic section; the first floor was administration; and the basement held the 200-ton printing press. The printing plates were engraved onto copper at Schloss Friedenthal near the Sachsenhausen concentration camp. The Spechthausen paper factory in Eberswalde was selected to research and develop the special linen paper for the banknotes.

Chief technical director Albert Langer, a mathematician and codebreaker by trade, was tasked with the key challenge: cracking the Bank of England’s sophisticated paper and serial numbering system.

The approach was clear: this was not to be a forgery or counterfeiting in the usual sense but authorized facsimile production.

Naujocks and his unit broke the monumental task into parts. First, they needed to replicate the unique banknote paper, a special rag-based paper with watermark designs. Next came mastering the intricate engraved plates for printing, including the delicate seated figure of Britannia that adorned each note – a detail so finely rendered that the German engravers nicknamed it “Bloody Britannia” in frustration. Finally, they had to unravel the Bank of England’s serial number sequences, which were essentially a guarded code.

Progress was slow but steady.

Using samples of real British notes, the team experimented with papermaking. They discovered that British notes used pure cotton rag paper with no wood pulp, giving it a distinct feel. To mimic it, the Germans sourced old rags, even simulating the effect of British laundry to get the right hue of paper. Under ultraviolet light their early paper still didn’t match – until Langer deduced that differences in water chemistry were to blame.

By treating the water to mirror England’s mineral content, the counterfeit notes glowed just like the real thing under UV lamps. The engraving of Britannia proved exceptionally challenging: it took veteran engravers months to produce a plate that satisfied them (her eyes in the counterfeit still weren’t perfect, one expert later noted). Meanwhile, Langer and a handful of banking consultants pored over years of British bank ledgers, trying to predict the serial numbering patterns.

The Operation would continue from 1939 until 1942 – with the workers managing to create convincing replicas of the British five and ten pound notes in circulation at the time. Albert Langer would claim that the counterfeiting unit managed to produce 200,000 five-pound notes and 200,000 ten-pound notes within this period.

Before these counterfeit notes could be deployed in any grand sabotage scheme, the project hit a snag.

Naujocks fell from favor (some accounts say he clashed with his superiors, or perhaps his usefulness had waned). He was removed from his post, and by early 1942 Operation Andreas had stalled.

The assassination of Reinhard Heydrich by Czechoslovak partisans in 1942 brought an end to the project.

The initial trove of forged banknotes was stashed away, never to be scattered over London as originally imagined. In-fact, most of those early counterfeits never left the vaults they were stored in.

Thus, the first phase of the Nazi plan fizzled out quietly.

Operation Andreas had proven that forging the British pound on a large scale was technically possible – the team had achieved remarkably convincing results – but internal politics and shifting priorities halted the effort.

However, this was not the end of the story. The counterfeit presses would soon be humming again under new management, as Heinrich Himmler decided to revive and repurpose the scheme for a different kind of covert war.

Before long, Operation Andreas would be reborn as Operation Bernhard, taking on even greater scale and secrecy.

–

Operation Bernhard

“Under my supervision and direction $600,000,000 worth of the finest British pound notes ever made outside the Bank of England were made by me and 140 involuntary assistants. The counterfeiting experts of Scotland Yard, the French Surete and even the U.S. Secret Service assured me, in tone of grudging admiration, that I was responsible for more counterfeit notes in a two-year period than all the known bogus money makers in those countries had turned out in the previous century.”

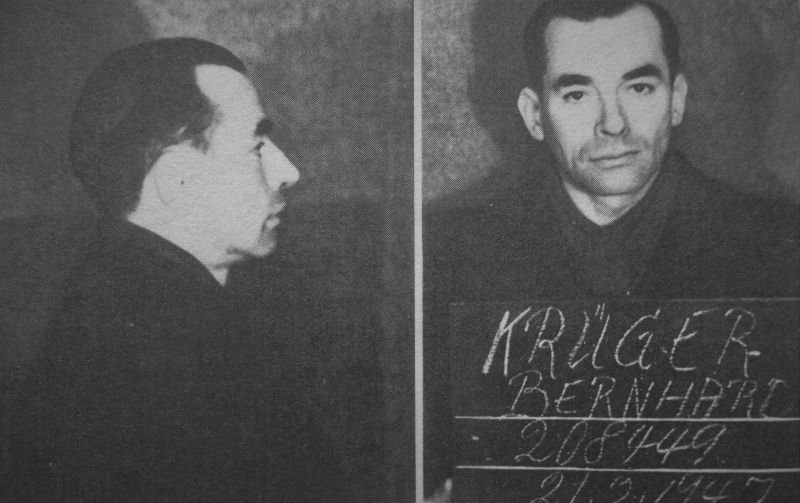

Bernhard Krüger, head of Operation Bernhard

As the prisoners arrived at Sachsenhausen Concentration Camp, they were unaware of the specific task that awaited them. SS Sturmbannführer Bernhard Krüger, however, had already been hard at work preparing the facilities and the conditions that would enable them to forge British banknotes on a massive scale.

The counterfeiters at Sachsenhausen, now numbering 140, up from the original 39 Jewish prisoners involved in Operation Andreas, came from fifteen nations and represented fifty-five trades or professions. Most were Jewish, but others were career criminals that had special skills useful to the operation.

In mid-1942, the Operation Andreas counterfeit plot was given new life – and a new name.

Heinrich Himmler, head of the SS and all Nazi security forces, decided to reactivate the scheme with a revised goal. Instead of trying to crash the British economy overnight (a prospect that seemed less realistic by 1942), the fake pounds would be used more surgically: to finance German espionage and covert operations abroad. British currency was hard international currency, accepted everywhere; if the Nazis could print their own endless supply, they could buy guns, bribe officials, and fund spies around the world.

The operation was resurrected under the codename Operation Bernhard, named for its new field commander: Bernhard Krüger.

Major Krüger was a methodical man from the SS security service who had previously run a unit forging foreign passports and documents. Now he was tapped to supervise the most ambitious counterfeiting enterprise ever attempted.

Krüger’s first task had been to pick up the pieces left from Operation Andreas. In a dusty Berlin workshop, he found the dormant printing presses, engraving plates, and materials from the earlier effort (some tools had rusted or warped out of shape). Armed with these and a mandate from Himmler himself, he set out to build a secret production line hidden from prying eyes.

The Sachsenhausen concentration camp, located just north of Berlin, was chosen as the site.

The prisoners that arrived at Sachsenhausen in September 1942 had been hand-picked by Krüger from various camps – mostly Jews with backgrounds in art, engraving, printing, banking, or chemistry.

Ultimately, some 142 prisoners were conscripted into this covert workshop, housed in Barracks 18 and 19, which were fenced off from the rest of the camp with extra barbed wire.

Among them were Hans Walter, a professional cyclist and engineer; Abraham Krakowski, an accountant; Paul Londo, a carpenter; and Jack Plepler, a painter and decorator. Individuals whose specialised skills (in printing, engraving, banking and the like) suddenly became their lifeline. The guards were sworn to secrecy. The imprisoned workers soon realized the dual nature of their assignment: it offered a chance at better conditions and life itself, but if they failed or if the Nazis lost use for them, their lives were on the line.

From the outset, Krüger cultivated a peculiar atmosphere in the counterfeiters’ barracks. Unlike the brutality common elsewhere in the camp, the prisoners in Operation Bernhard received unusually humane treatment – relatively speaking. Krüger addressed them politely as “Sie” (formal “you”), provided slightly improved rations, and even supplied amenities: cigarettes, newspapers, and a radio for news; a ping-pong table for recreation; and extra blankets against the cold.

Prisoners would note that Krüger was not the archetypal Nazi officer one might expect; a pudgy, receding man with a penchant for double entendre.

On some evenings the forger-prisoners staged cabaret shows and concerts, with SS guards in the audience. Compared to the hell outside their barracks, it felt like a surreal “gilded cage.” One survivor, Adolf Burger, later said they were like “dead men on holiday” – living in obscene comfort by concentration camp standards, yet knowing that death loomed the moment they ceased to be useful. Burger and others never forgot Krüger’s opening speech to them: do the job well and you’ll live, sabotage it and you’ll be killed.

Survival meant cooperation.

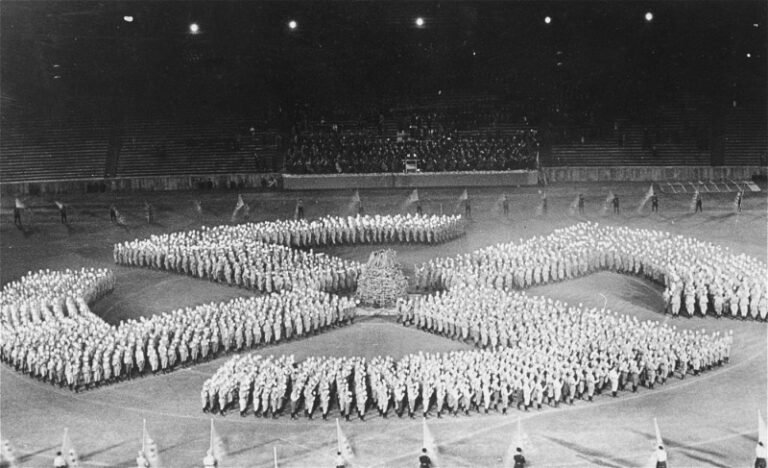

By early 1943, the counterfeit factory at Sachsenhausen was up and running. Twelve thousand sheets of special banknote paper per month arrived from a secret paper mill, each sheet large enough to fit four banknotes. Printing presses pounded day and night in two shifts of prisoner workers. Each stage of production was overseen by an inmate specialist – one for engraving, one for plate-making, one for printing, one for quality control.

One prisoner, Oskar Stein, effectively acted as the foreman, managing daily operations under Krüger’s watch. They now focused on four denominations (£5, £10, £20, and £50 notes) instead of just the five and ten pounds of Operation Andreas, albeit using and refining the techniques developed during that earlier scheme.

The quality soon reached new heights. In fact, the German high command was delighted to discover the forgeries were virtually undetectable. The fake notes had proper watermarks, crisp engraving, and correct serial numbers. To give them the feel of circulation, batches of fresh prints were “aged” by hand: prisoners with dirty fingers would shuffle and thumb the notes, others would fold and crumple them slightly, and clerks would jot typical British names or bank notations in pencil on the margins (just as real banknotes often bore scribbles).

The end product looked and felt utterly authentic – Bank of England notes that even Bank of England cashiers struggled to tell apart from real currency.

At its peak, Operation Bernhard produced an astonishing volume. By 1944, roughly 65,000 forged notes were rolling off the presses each month – tens of millions of pounds in aggregate. So pleased were the Nazi authorities that they even awarded War Merit medals to a dozen of the prisoner-forgers (Jewish inmates decorated for helping the Third Reich, albeit under duress).

The counterfeit pounds were sorted by quality into categories: category one, were for shipment to England (through Chicago and Switzerland). The next grade was to be sent to the English colonies. The third grade was to be used in sabotage operations at the front and in Africa and Egypt. Grade four notes were to be dropped over England to disrupt the economy and the poorest of the forgeries were discarded.

The only major limitation of the fake money was the one problem Naujocks’s team never fully cracked – the serial number algorithm. Eventually the Germans resorted to recycling serial numbers from genuine notes that had been withdrawn from circulation, to avoid impossible duplicates showing up in the Bank of England’s ledgers.

This shortcut would later prove their undoing when the British caught on.

Himmler, impressed with Krüger’s success, expanded the mission in 1944. He ordered the unit to attempt another feat: counterfeit the American $100 bill. Forging U.S. “greenbacks” posed new challenges – the paper had tiny red and blue silk fibers, and the artwork was even more intricate than Sterling notes, including fine intaglio printing that left raised ink lines on the paper. The Sachsenhausen crew dutifully set to work.

To assist, they brought in a convicted Jewish forger named Salomon Smolianoff, a talented criminal who had counterfeited currency in pre-war Europe. Smolianoff had been forging British 50-pound notes since 1927 and entered Nazi custody after being arrested and jailed in Amsterdam for counterfeiting. His arrival caused some resentment among the captive team (many of whom were professionals or political prisoners, not common criminals), but his expertise was valuable. Under pressure from above, the prisoners intentionally slowed their progress on the dollar project – they knew that once they succeeded, the SS would have little reason to keep them alive. Krüger, aware of this dynamic, tacitly allowed the work to drag on. By early 1945, the team had achieved a near-perfect fake of the U.S. $100 (sans serial numbers, which were still being studied), but mass production of dollars never got underway before events overtook them.

The counterfeiting of French currency was also undertaken as part of Operation Bernhard, although according to SS officer Krüger’s testimony only the plates for creating the money (fifty, one hundred, and possibly five hundred francs) were produced and not the actual currency.

From 1943 onward, the counterfeit British pounds from Operation Bernhard quietly entered circulation via clandestine channels. The fake notes were laundered through a special unit run by SS Major Friedrich Schwend, an operative in charge of converting the forged cash into real assets. Bundles of Bernhard notes were smuggled into neutral countries – Switzerland, Sweden, Turkey – and exchanged on the black market or used to purchase goods and intelligence.

Some funds went to pay Nazi spies, including the famous double agent Elyesa Bazna (code-named “Cicero”), who accepted a suitcase full of British pounds for his espionage in Ankara – unaware that most of the notes were counterfeit.

Other portions were used to buy influence or arms: for example, a cache of fake sterling reportedly helped finance the daring rescue of Italian dictator Benito Mussolini by German commandos in 1943 – approximately £25,000 of Operation Bernhard currency was used in bribes.

By the end of the war, many of the forged pounds had been spent or scattered far afield, while a large reserve remained in SS hands for future schemes.

Operation Bernhard ran until the final months of World War II, when the Third Reich’s imminent collapse forced a frantic shutdown. In early 1945, with Soviet and Western Allied forces closing in, the SS relocated the counterfeiting unit and its prisoners from Sachsenhausen to camps in Austria.

By the time Sachsenhausen was evacuated in April 1945, according to Chief Inspector William Rudkin of the London Metropolitan Police, the printing presses there had produced 3,945,867 £5 notes, 2,398,981 £10 notes, 1,337,335 £20 notes and 1,282,902 £50 notes – a grand total on £134,610,945.

These 8.9 million banknotes, worth more than £130 million at the time, would be equivalent to over £3 billion today.

Fortunately, events moved too quickly for the Nazis to exploit their trove to its full potential.

–

The British Discover the Forgeries

“Where large sums of money are concerned, it is advisable to trust nobody”

Agatha Christie, Endless Night

For a time, the Nazi counterfeiters appeared to have achieved the impossible – creating fake British pounds that circulated without detection.

But as the saying goes, “murder will out,” and even a perfect crime can unravel through a small mistake.

The Bank of England had been alerted as early as 1939 that Germany might attempt a counterfeiting assault (thanks to a tip from a foreign informant), but the Bank’s experts remained confident that their notes could not be forged on a large scale. By 1943, however, subtle warning signs began to surface.

The breakthrough in exposing Operation Bernhard came from an eagle-eyed bank clerk in Morocco.

In mid-1943, this clerk noticed something odd about a £10 note presented for routine cashing at a British bank branch. The note’s serial number struck him as familiar – in fact, he realised that exact number had been recorded already when a similar note was cashed earlier.

Since no two genuine Bank of England notes share the same serial, the only explanation was that one of the notes was a forgery. Word was quickly passed up the chain.

The discovery caused alarm at the Bank’s Threadneedle Street headquarters: if a counterfeit £10 was circulating abroad with a duplicate serial number, how many more might be out there?

Investigation soon confirmed that high-quality fake notes had indeed infiltrated international markets. British intelligence and bank officials quietly collected suspect notes from banks in neutral countries. The counterfeits were so convincing that it took careful examination to identify them – often the clue was not a flaw in printing, but a telltale duplication of a serial number that had already been logged in Bank of England ledgers as paid and retired from circulation.

Bryan Burke, author of the book Nazi Counterfeiting of British Currency During World War II, has since recorded 28 differences between the genuine British White Notes and an Operation Bernhard note.

Once aware of the threat, the Bank of England took rapid action to mitigate potential damage. In 1943 it ceased issuing any new notes in denominations above £5 (effectively demonetizing the £10, £20 and £50 notes so prized by the counterfeiters). An emergency series of smaller denomination notes with additional security features (such as metallic security threads) was prepared, and strict warnings were circulated to banks and money changers to be on the lookout.

By war’s end, the British authorities had contained the situation before it could spiral into financial chaos. Thanks to the serial-number sleuthing, they identified many of the forged notes and largely kept them out of the UK domestic economy.

In fact, as Allied forces advanced into Europe in 1944–45, British agents were already on the trail of the source. Captured German documents and interrogations of prisoners began to shed light on a massive counterfeiting operation.

The full scope of Operation Bernhard was only revealed after the war, stunning the Bank of England. (One estimate suggested that around one in ten banknotes circulating in war-torn Europe in 1945 was a Bernhard forgery.) Small wonder that the Bank felt compelled to do a total redesign of British paper money after the war; the old “white notes” were discontinued entirely in 1945, replaced by a new colorful series in 1948 to start with a clean slate.

For the men of Operation Bernhard, British awareness of their handiwork was merely academic recognition – they had more immediate concerns as the Third Reich crumbled around them.

The Allied armies’ approach meant the counterfeiters’ secret had to be evacuated or erased.

In the spring of 1945, the project reached its dramatic finale, far from Berlin.

–

The Loot In The Lake - The End Of Operation Bernhard

“O, she is fallen

Into a pit of ink, that the wide sea

Hath drops too few to wash her clean again.”

William Shakespeare, Much Ado About Nothing

As Nazi Germany collapsed in April 1945, Operation Bernhard was wound down amid frantic efforts to hide evidence of its existence.

The counterfeiters and their equipment were moved from camp to camp in the war’s final weeks. First reaching Mauthausen, then Redl-Zipf concentration camp, then Ebensee.

Work was initially intended to continue in Redl-Zipf, where the Operation Bernhard prisoners were expected to rebuild the equipment from Sachsenhausen inside a series of caves that had previously been used as the manufacturing base for V1 and V2 rockets. In early May 1945, however, Operation Bernhard was abruptly shut down, and the prisoners were moved from their hidden caves to the nearby Ebensee concentration camp.

Divided into three groups, they awaited transport by truck, unaware that the SS had secretly ordered their execution once all groups arrived.

The first two groups reached Ebensee quickly, separated from the camp’s general prisoners to await their fate. But during the third trip, the prisoner transportation truck broke down, forcing the exhausted prisoners to march for two days. Crucially, the execution order required all prisoners to be killed together, unintentionally saving the first groups.

As Allied troops rapidly approached, panicking SS guards abandoned their plans on May 5th, releasing the first two groups into the main camp. When the third group finally arrived later that afternoon, the guards hastily freed them as well before fleeing into the hills.

The next day, American forces entered Ebensee, liberating everyone who remained.

Of the 142 men tasked with counterfeiting currency for Operation Bernhard, all miraculously survived the war.

Bernhard Krüger returned to his own home, where he remained until 1946 when he surrendered himself to the British authorities, who questioned him in depth about his wartime counterfeiting.

After undergoing ‘deNazification’, Krüger lived out a quiet life in West Germany – working for the same Hahnemühle paper company that had supplied the material for Operation Bernhard.

At least five of the prisoners who took part in the counterfeiting operation published their memoirs after the war. Some would also testify in favour of Krüger during his deNazification process, stating he had been responsible for saving their lives.

The fate of the forged currency would become fodder for an untold number of conspiracy theories.

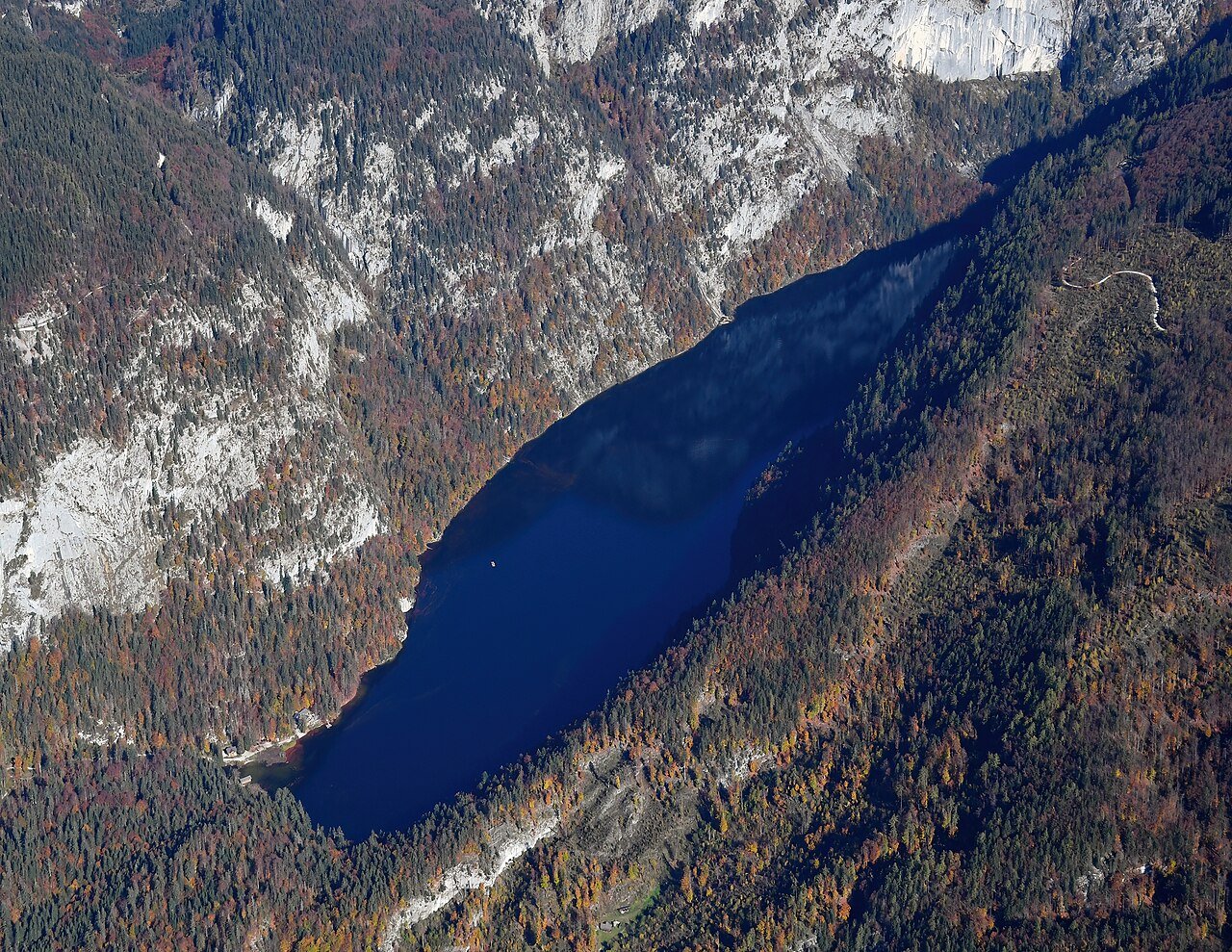

In late April 1945, a convoy of SS officers transported crates filled with banknote printing plates, presses, and remaining bundles of forged pounds into the Austrian Alps. At a secluded mountain lake named Toplitzsee (Lake Toplitz), the SS men unceremoniously dumped the heavy boxes into the deep water. Perhaps they imagined the secret would stay sunken forever beneath the pine-covered slopes and dark, brackish depths of that alpine lake.

The lake’s depth and layers of low-oxygen water helped preserve the dumped materials for years. Local folklore soon sprang up about Nazi treasure resting at the bottom of Toplitzsee. Indeed, not all the forged money had been destroyed – thousands of notes were simply ditched in the water, where they remained hidden but intact.

In the immediate aftermath of the war, scattered Bernhard notes turned up here and there.

Allied troops occupying Germany occasionally stumbled on stashes of suspiciously crisp banknotes. In one ironic twist, Jewish refugees used some of the recovered counterfeit pounds to aid underground migration efforts for survivors – putting Nazi fake money to good use after the Holocaust. But the bulk of Operation Bernhard’s output lay underwater.

Lake Toplitz gained an aura of mystery: was there more than just counterfeit money down there? Rumors swirled that the Nazis had also sunk crates of gold, stolen jewels, or secret documents. The lure of possible riches drew adventurers and divers in the 1950s.

A series of dives in 1959 coordinated by the German magazine, Stern, finally brought Toplitzsee’s secrets to light. Divers recovered chests filled with waterlogged banknotes – still bundled in packs – along with steel printing plates and other equipment from the lake bottom. The Bank of England, once the notes were examined, confirmed them as the long-lost products of Operation Bernhard. (Many bore a clear overprint “FORGED” or “FACSIMILE” indicating they were counterfeit specimens.)

In all, roughly £9 million in fake notes were retrieved. The Austrian authorities eventually had the recovered notes pulped or burned, and the printing plates were defaced to prevent any further misuse.

The legend of the Nazi “lake treasure” persisted, however.

Even after the counterfeit money was fished out, treasure hunters speculated that more valuables remained hidden. In the early 1960s, an expedition ended in tragedy when a diver died searching the lake’s depths, fueling conspiracy theories that something sinister still guarded the sunken trove. Over the decades, occasional searches have been conducted, but no great cache of Nazi gold has ever been found in Toplitzsee – only the detritus of Operation Bernhard’s last chapter.

Thus, the grand counterfeiting plot concluded not with a triumphant collapse of the British economy, but with forged banknotes soaked in an Austrian lake.

What could have been a financial weapon of mass destruction was instead reduced to soggy pulp and a footnote in the annals of World War II.

Yet, as we will consider next, Operation Bernhard’s scale and ambition still rank it among the most extraordinary counterfeit operations in history – if not the largest of all time.

–

The Greatest Counterfeiting Operations in History

“Operation Bernhard delivered “the most bogus money over the longest period of safety; …the finest counterfeit notes ever seen; …the world’s largest distribution network; …the greatest number of conspirators and prisoner employees; …and the finest equipment ever assembled for a counterfeiting operation.”

Murray Teigh Bloom, author of The Man Who Stole Portugal

Operation Bernhard remains a singular episode in the annals of crime and warfare.

Its sheer scale and state-backed sophistication prompt the inevitable question: was it truly the largest counterfeiting operation in history? By many measures, the answer appears to be yes.

To appreciate that standing, it’s worth comparing Bernhard with other famous (or infamous) counterfeiting schemes across time.

Prior to the Second World War, no government-run forgery campaign came close in scope.

- The British sabotage of American Revolutionary currency, while effective, amounted to perhaps a few hundred thousand fake dollars – a far cry from the Nazi effort.

- The clandestine British operation to forge French assignats in the 1790s was significant in its day, but again limited by technology and the shorter lifespan of the paper money involved.

Private criminal enterprises have had notable successes – for instance, the great Portuguese bank note scandal of 1925, when a forger named Alves dos Reis managed to print millions in unauthorized banknotes and nearly took over the Bank of Portugal. That caper flooded one country with counterfeit currency (and ultimately wrecked its economy), but in absolute value it was still smaller than Bernhard and was not a wartime operation.

In modern times, there have been a few contenders for the crown of “largest counterfeit operation.”

- During the late 20th century, rumors swirled that North Korea was printing so-called “super-dollars” – extremely high-quality forgeries of U.S. $100 bills – as a form of economic warfare or sanctions evasion. Over decades, North Korean presses may have produced tens of millions of dollars in fake U.S. currency, enough that the Secret Service eventually had to redesign the $100 bill to thwart them. Yet even the notorious “supernote” operation, while global in reach, is believed to have generated a sum that pales next to the £132 million (equivalent to several billion USD today) pumped out by Operation Bernhard in just a few years.

- On the purely criminal side, the largest individual counterfeiter on record is a Canadian man named Frank Bourassa, who in the early 2010s printed an estimated $250 million in fake U.S. banknotes in a clandestine printing shop. Bourassa’s feat was mind-boggling as a solo venture, but it was quickly shut down by law enforcement and never threatened a national economy.

What sets Operation Bernhard apart is not just its scope but also that it was a concerted, government-organized plot, executed with the full resources of a nation-state and with the intent to disrupt global finance. It combined the cunning of a criminal mastermind with the budget of a government agency and the ruthlessness of a wartime regime.

In every aspect – production volume, quality, breadth of use, and ambition – the Nazi scheme was a record-breaker.

It forced the Bank of England to take measures unprecedented in its history, and it left a legacy that experts in currency security still marvel at.

In hindsight, one can debate whether Operation Bernhard achieved anything lasting for the Nazis. It certainly caused inconvenience and expense for the British (who had to withdraw banknotes and redesign their currency). It financed some German clandestine activities for a time.

But it did not come close to toppling the British economy or altering the war’s outcome.

If anything, its biggest impact was psychological: after the war, the mere knowledge of how far the Nazis went – turning concentration camp prisoners into a forced assembly line of counterfeiters – added yet another layer to the horrors and perversities of the Third Reich.

**

Conclusion

So, was it the largest counterfeiting operation in history?

By the numbers and by the audacity, yes – it stands atop the list.

Other episodes have rivaled it in cleverness or in local impact, but no scheme before or since has combined such massive output of fake currency with such global intent. Operation Bernhard set a dark record that, one hopes, will never be exceeded.

***

If you’ve enjoyed reading this article, consider booking one of our private guided tours of Berlin.

HISTORICAL ARTICLES

Mythbusting Berlin

Are There Any Nazi Statues Left In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

Visitors to Berlin often arrive expecting to find the physical remnants of the tyranny of the 20th century still standing – statues of dictators, triumphal arches, or bronze idols. Instead, they often find none. The stone symbols and statues of the Third Reich are still gazing down on them, however, hiding in plain sight. But why are there no statues of Hitler? Did the Allies destroy them all in 1945, or is the truth stranger

Could The Western Allies Have Captured Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

To contemplate a Western Allied capture of Berlin in 1945 is to challenge the established endgame of the Second World War. What was the true military and logistical feasibility of a Western Allied assault on the Nazi capital? What factors truly sealed Berlin’s fate, and what might have changed had the Allies pushed eastward?

Answering these questions means delving into the complex interplay of logistics, political maneuvering, and the competing visions for a post-war world

Did Any Of The Rothschild Dynasty Die In The Holocaust? – Mythbusting Berlin

The Rothschild name is synonymous with immense wealth, influence, and persistent conspiracy theories—especially during the era of Nazi Germany. Often targeted by antisemitic propaganda, the family’s survival during World War II has sparked myths about their supposed immunity from Nazi persecution. But did any Rothschild family member actually perish in the Holocaust? This article explores that compelling question, unraveling historical misconceptions and revealing the reality behind one of Europe’s most famous dynasties.

Did Frederick The Great Introduce The Potato To Germany? – Mythbusting Berlin

One of the more bizarre claims to fame attributed to the first King of Prussia is that the man who would go down in history known as Frederick the Great introduced the potato to Germany during his reign back in the 1700s. This starchy root vegetable has undoubtedly become a staple part of German cuisine – an essential addition to any plate of Schnitzel, Schweinshaxn, and Königsberger Klopse – however, whether Frederick the Great is

Did Hitler Escape To Argentina In 1945? – Mythbusting Berlin

Although Nazi leader, Adolf Hitler, certainly remains an inescapable figure, could there be any truth to the story of his escape to Argentina in 1945? That the most wanted man on earth could simply vanish, to spend the rest of his life peacefully in South American obscurity captivates imaginations. Yet, despite numerous investigations, this tale persists primarily as myth—fueled by speculation, hearsay, and conspiracy theories.

Did Hugo Boss Design The Nazi Uniforms? – Mythbusting Berlin

The idea that Hugo Boss – the man whose name now adorns expensive suits and fragrances – was the creative genius behind the Nazi uniforms suggests a terrifying collision of haute couture and holocaust – a marriage of high style and high crimes. The image is striking: a German tailor sketching the ultimate villain’s costume. But history, as usual, is far messier, more bureaucratic, and more banal than the internet memes suggest. To understand who

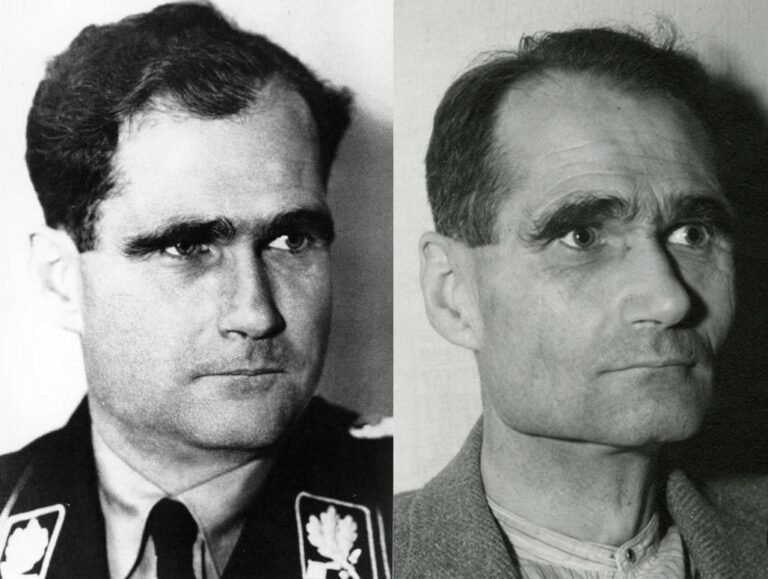

Did Rudolf Hess Really Commit Suicide? – Mythbusting Berlin

On a summer’s day in 1987, the last Nazi war criminal of the Nuremberg trials was found dead in a prison built for hundreds, yet for two decades, housed only him. The official verdict was suicide, a straightforward end to a life defined by fanaticism, delusion, and contradiction.

But the simplicity of the report belied the complexity of the man and the 46 years he had spent in Allied custody. In the meticulously controlled

Did The Nazis Develop Nuclear Weapons? – Mythbusting Berlin

The Nazi obsession with super-weapons became so serious in the closing stages of the Second World that Adolf Hitler personally believed that such ‘Wunderwaffen’ both existed in a usable form – and would save the country from defeat. Had the Nazis managed to develop nuclear weapons by 1945 – the outcome of the war would surely have been different. But how close were Hitler, Himmler, and his henchmen to developing an A-bomb?

Did The Nazis Invent Decaf Coffee? – Mythbusting Berlin

Persistent rumors claim that Nazis preferred their coffee anything but pure, leading some to wonder if they might have influenced the development of decaffeinated coffee. Although decaf was already widely available across Europe by the mid-20th century, speculation continues: could the Nazis really have played a role in popularizing—or even discovering—this caffeine-free alternative, or is this simply another caffeinated conspiracy cooked up to sensationalize an ordinary historical detail?

Did The Nazis Invent The Bicycle Reflector? – Mythbusting Berlin

The fruits of wartime ingenuity are plenty – so many, in-fact, that it has become somewhat of a worn cliche that as the guns start firing the innovators get to work, often solving problems while providing more problems for the enemy to overcome.The kind of progress that results in the production of newer improved, more lethal weapons, such as to increase the chances of victory.

Did The Nazis Run The Largest Counterfeiting Operation In History? – Mythbusting Berlin

During the Second World War the Nazis masterminded an astonishing plot to destabilise Britain by flooding its economy with counterfeit banknotes. Crafted in secret by concentration camp prisoners, this forged fortune became the most ambitious counterfeiting operation ever attempted. But was it history’s largest? Dive into the extraordinary tale of Operation Bernhard,

rife with deception, survival, and intrigue—revealing the truth behind one of the Third Reich’s most audacious schemes and its surprising legacy.

Did The Second World War End In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

When is a war ever truly over? When the last shot is fired in anger would seem like the best measure. Rarely, though, is it possible to gain insight into such a moment.

Remarkably, a record still exists of such a moment at the end of the First World War on the Western Front. A seismic register and recording of the last belching battery of British guns firing artillery across no-man’s-land, followed by a profound

Did The Spanish Flu Pandemic Help The Nazis Take Power? – Mythbusting Berlin

The devastating Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918-1919 struck amid Germany’s post-war turmoil, compounding social instability, economic hardship, and widespread political disillusionment. Could this catastrophic health crisis have indirectly paved the way for Nazi ascension? While often overshadowed by war and revolution, the pandemic’s profound psychological and societal impacts arguably contributed to the perfect storm, enabling extremist ideologies—including Nazism—to gain popularity and ultimately seize power in a fractured Germany.

Have Adolf Hitler’s Remains Been DNA Tested? – Mythbusting Berlin

In the smouldering ruins of Berlin in 1945, the world’s most wanted man vanished. Did Adolf Hitler, as official history attests, die by his own hand in the Führerbunker? Or did he escape, fuelling a thousand conspiracy theories that have echoed for decades? For years, the Soviets claimed to hold the gruesome proof of his death: a skull fragment and a set of teeth, locked away in Moscow archives. But in an age of definitive

How Did The Nazi Concentration Camps Differ From The Soviet GULAG?

The Nazi concentration camps and Soviet Gulag system have often been conflated in popular imagination—twin symbols of twentieth-century totalitarian horror. Yet the two systems operated on fundamentally different principles. One extracted labor to fuel industrialisation while accepting mass death as collateral damage; the other evolved into purpose-built machinery of genocide. Understanding these distinctions isn’t merely academic—it reveals how different ideologies produce different atrocities, and why Germany and Russia reckon with these legacies so differently today.

How Long Did It Take To Build The Berlin Wall? – Mythbusting Berlin

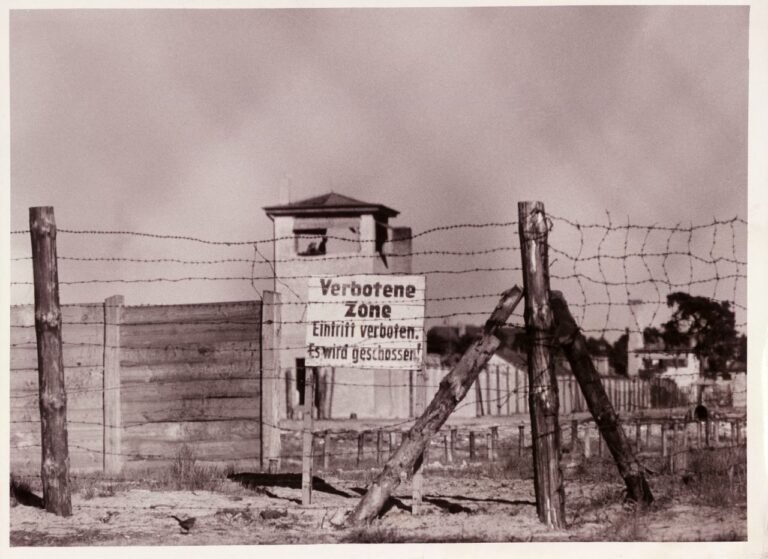

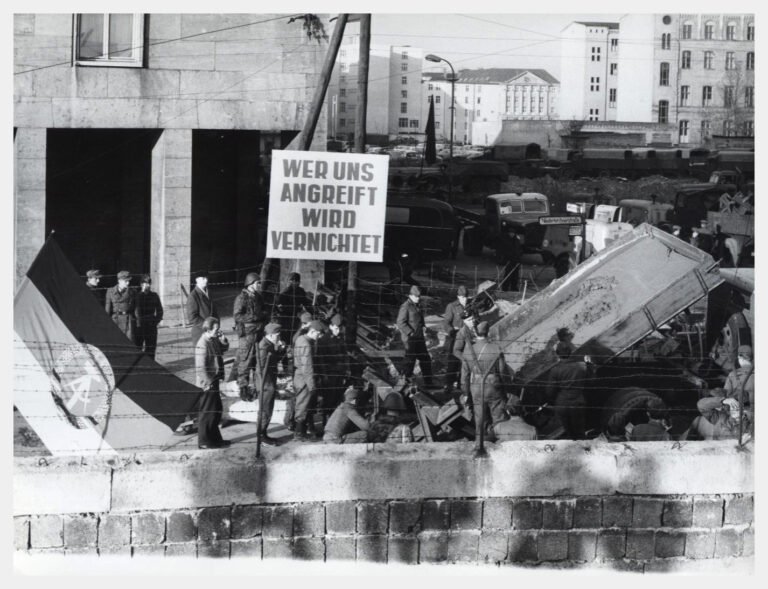

It is one of the most enduring images of the 20th century: a city divided overnight. The popular narrative tells us that Berliners went to sleep in a unified city and woke up in a prison. While the shock of August 13th 1961, was very real, the idea that the ‘Wall’ appeared instantly is a historical illusion. The physical scar that bisected Berlin was not a static creation, but a living, malevolent beast that evolved

How Many Assassination Attempts On Adolf Hitler Were There? – Mythbusting Berlin

Nazi leader, Adolf Hitler, projected an aura of invincibility, a man of destiny shielded by providence. But behind the carefully constructed image of the untouchable Führer lies a story of constant threat, of bombs that failed to detonate, and errant bullets that missed their mark. Unearth the hidden history of the numerous attempts on Hitler’s life as we explore the courage of those who tried to change the course of history and the devil’s luck

How Many Jews Died In The Holocaust? – Mythbusting Berlin

The answer to the question posed of how many Jews died in the Holocaust is a simple one: too many. That merely one death was an unforgivable obscenity is a fundamental and necessary realisation in understanding the capriciousness of this unparalleled racial genocide. To comprehend, however, the full number of Jews murdered in Europe by the Nazi regime in the 1930s and 1940s is a detective story of epic proportions: the evidence overwhelming, multifaceted, and

How Many People Died Trying To Escape East Germany? – Mythbusting Berlin

The image of the Berlin Wall is seared into our collective memory, a concrete symbol of Cold War oppression. We think of the daring escapes and the tragic deaths of those who failed. But that well-known number is only a fraction of the truth. The story of those who died trying to escape East Germany is far broader and more complex than most imagine, stretching along a thousand-kilometer border and out into the cold waters

How Old Is Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

A relatively new arrival in Europe, Berlin is over 1000 years younger than London, nevermind Rome or Athens, Jerusalem or Jericho. Just how old is Berlin though?

A question fraught with false assumptions and distortions – that has more often than not been answered with propaganda as it has with the cold hard truth.

Was Adolf Hitler A Drug Addict? – Mythbusting Berlin

Solving the enigma of the ‘Führer’ has become a preoccupation for many, since the arrival of the Austrian-German onto the world stage – although moving beyond the mythology without falling into the trap of prejudically extrapolating on the psychopathography of Hitler or demonising so as to excuse his actions has proven problematic. What to make of the man who became more than the sum of his masks? The painter; the military dilettante, the mass murderer,

Was Adolf Hitler A Freemason? – Mythbusting Berlin

History abhors a vacuum, but adores a mystery. Such is the speculative fiction suggesting a secret allegiance behind the rise of the Third Reich – that the catastrophe of the Second World War was orchestrated from the shadows of a Masonic lodge. The image of Adolf Hitler—the drifter from Vienna turned dictator—as a covert initiate of the very brotherhood he publicly reviled, however, creates a paradox that collapses under scrutiny. As when we unlock the

Was Adolf Hitler Gay? – Mythbusting Berlin

In the shadowy corridors of Third Reich history, few questions provoke as much tabloid curiosity and scholarly exasperation as the sexuality of Adolf Hitler. For decades, rumors have swirled—whispered by political enemies in 1930s Munich, psychoanalyzed by American spies in the 1940s, and sensationalized by revisionist authors today. Was the dictator who condemned thousands of men to concentration camps for “deviant” behavior hiding a secret of his own? By peeling back the layers of propaganda,

Was Adolf Hitler Jewish? – Mythbusting Berlin

Was the dictator who orchestrated the murder of millions of European Jews secretly one of them? It is perhaps the darkest irony imaginable, a story whispered for decades in backrooms, bars, and conspiracy forums alike. The most-common rumour – the ‘Frankenberger Myth’ – suggests that Adolf Hitler’s paternal grandfather was Jewish, a secret so damaging it could have unraveled the entire Nazi regime. But where does this claim come from? And, more importantly, is there

Was Currywurst Invented In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

Explore the story behind what many consider Berlin’s most iconic snack—the ever-so-humble Currywurst. Often hailed as an enduring symbol of culinary creativity amid Cold War scarcity, this humble dish has inspired fierce debate about its true origin. But was it genuinely invented here in Berlin, or have proud locals simply adopted and elevated this spicy street-food favorite into legendary status all their own?

Was Fanta Invented By The Nazis? – Mythbusting Berlin

As one of the most secretive organisations in the world, the Coca Cola corporation refuses to share its secret recipe with anyone. Famously insisting only on shipping the base syrup of its drinks to plants around the world to be carbonated and distributed.

This combined with the trade limitations of the Second World War may have led to the introduction of one of the most popular soft-drinks in the world. But could it be true:

Was Frederick The Great Gay? – Mythbusting Berlin

Frederick II of Prussia, better known as Frederick the Great, is often remembered as the archetypal enlightened monarch – a brilliant military commander, patron of the arts, and learned philosopher. Yet behind the stern portraits of this 18th-century warrior-king lies a personal life long shrouded in intrigue and speculation. Intrigue around the king’s sexual orientation has persisted through the centuries, chiefly revolving around one question: Was Frederick the Great gay?

Was Henry Ford A Nazi? – Mythbusting Berlin

US auto tycoon, Henry Ford, holds the ignominious distinction of being the only American Adolf Hitler praised by name in his National Socialist manifesto: ‘Mein Kampf’. This was not, as it turns out, the only connection between Ford and the Party of Hitler, Himmler, and the Holocaust.

Ford’s overt affinity with the Third Reich reveals a troubling past. How deep these connections ran, and how consequential they were for both sides, is a chapter

Was The Colour Blue Invented In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

Tracing the true history of blue—from ancient Egyptian dyes to the accidental discovery of Prussian Blue in a Berlin lab. We’ll debunk myths about seeing blue, explore colonial indigo plantations, scale mountains with a cyanometer, and trace Van Gogh’s starry skies—all to answer one question: how did Berlin shape our understanding of the world’s rarest color?

Was The Döner Kebab Invented In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

Unlikely icon of immigrant success; fast food symbol of the working class; over-hyped midnight disco eat; or culturally appropriated cuisine? Its influence goes far beyond layers of seasoned meat and fresh vegetables stuffed into pita bread. But does Berlin deserve credit as the Döner Kebab’s true birthplace, or has the city merely refined and popularized a culinary tradition imported from elsewhere?

Was The Fall Of The Berlin Wall An Accident? – Mythbusting Berlin

On a seasonally crisp night in November 1989, one of the most astonishing events of the 20th century occurred. After twenty eight years, three months, and twenty eight days of defining and dividing the German capital, the Berlin Wall ceased to exist – at least in an abstract sense. Although the removal of this symbol of the failure of the East German system would take some time, its purpose – as a border fortification erected

Was The Nazi Party Democratically Elected? – Mythbusting Berlin

The myth persists that Adolf Hitler rose to power through popular democratic choice. Yet history reveals a darker, more complicated truth. Hitler’s ascent involved exploiting democratic institutions, orchestrating violence, propaganda, and political intrigue—not a simple election victory. Understanding how Germany’s democracy collapsed into dictatorship helps illuminate the dangerous interplay between public desperation, elite miscalculations, and extremist ambition, providing crucial lessons for safeguarding democracy today.

Were The Allied Bombings Of Germany War Crimes? – Mythbusting Berlin

The history of the Allied bombing of Germany during the Second World War still triggers fierce debate. Was reducing cities to rubble a necessary evil – justice from above in a just war – or an unforgivable crime? Can the intentional targeting of civilians ever be justified as militarily necessary?

In a conflict where all rules seemed to vanish, an even more pertinent question persists: by the very standards they would use to judge their

Were The Nazi Medical Experiments Useful? – Mythbusting Berlin

Before the Nazi period, German medicine was considered the envy of the world – a shining monument to progress. But deep within that monument, a rot was spreading, one which would collapse the entire structure into an abattoir. From the wreckage, we are left with a profoundly uncomfortable inheritance: a moral enigma wrapped in doctor’s whites.

What to make of the data, the images, and the terrible knowledge gleaned from unimaginable human suffering. Whether

What Are The Origins Of The Nazi Salute? – Mythbusting Berlin

A specter is haunting the modern mind, a gesture so charged with the dark electricity of history that its mere depiction can unleash a storm of controversy.

It is a simple movement: the right arm, stiff and straight, raised to the sky. But in that simplicity lies a terrifying power, a symbol of a regime that plunged the world into an abyss and a chilling reminder of humanity’s capacity for organised hatred.

This

What Are The Origins Of The Nazi Swastika? – Mythbusting Berlin

Long before the legions of the Third Reich marched beneath its stark, unnerving geometry, the swastika lived a thousand different lives. It was a symbol of breathtaking antiquity, a globetrotting emblem of hope and good fortune that found a home in the most disparate of cultures. To even begin to understand its dark 20th-century incarnation, one must first journey back, not centuries, but millennia.

What Are The Pink Pipes In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

A first-time visitor to Berlin could be forgiven for thinking the city is in the midst of a bizarre art installation. Bright pink pipes, thick as an elephant’s leg, climb out of the ground, snake over pavements, arch across roads, and disappear back into the earth. Are they part of a complex gas network? A postmodern artistic statement? A whimsical navigation system? These theories, all logical, are all wrong. The truth is far more elemental,

What Do The Colours Of The German Flag Symbolise? – Mythbusting Berlin

What does a flag mean? Is it merely a coloured cloth, or does it hold the hopes, struggles, and identity of a nation? The German flag, with its bold stripes of black, red, and gold, is instantly recognisable. But the story of its colours is a tumultuous journey through revolution, suppression, and reinvention. The common explanation for their symbolism is a simple, romantic verse, yet the truth is a far more complex and contested tale,

What Happened To Adolf Hitler’s Alligator? – Mythbusting Berlin

It is often said that you can tell a lot about a person by their relationship with animals; that owners often come to look and behave like their pets. Or is it perhaps more that people choose their pets to correspond to their personality? Nazi leader Adolf Hitler’s love of dogs, for example, is well documented but what is there to make of his relationship with reptiles?

What Happenened To The German Royal Family? – Mythbusting Berlin

When the smoke cleared over the trenches in November 1918, the German Empire had evaporated, and with it, the divine right of the Hohenzollern dynasty. Conventional wisdom suggests the family simply vanished into the sepia-toned obscurity of history books—exiled, forgotten, and irrelevant. But dynasties, like weeds in a landscaped garden, are notoriously difficult to uproot entirely. The story of the German royals did not end with the Kaiser’s flight to Holland; it merely shifted gears.

What Is The Difference Between Fascism & Nazism? – Mythbusting Berlin

While the terms ‘Fascist’ and ‘Nazi’ are often bandied around interchangeably as shorthand for tyranny – Italian fascism and German National Socialism were distinctly different beasts. Albeit ideological kin. One an ideology of state-worship, born from post-war chaos and national pride; the other built upon a fanatical, pseudo-scientific obsession with race. Two peas in the same totalitarian pod – twins in tyranny – more succinctly summarised as the Nazi chicken to the Fascist egg.

What Was Checkpoint Charlie? – Mythbusting Berlin

Checkpoint Charlie remains among Berlin’s most visited historical sites, famed worldwide for its significance during the Cold War. Originally established as a modest border-crossing point, it evolved dramatically over the decades into an international symbol of freedom, espionage, and intrigue. Today, critics and locals often dismiss it as little more than a tourist trap—Berlin’s Disneyland—but how exactly did Checkpoint Charlie get its peculiar name, and what truths hide behind its popularity?

What Was Prussia? – Mythbusting Berlin

Prussia’s legacy is both remarkable and contentious—once a minor duchy, it rose dramatically to shape modern European history. Renowned for military discipline, administrative efficiency, and cultural sophistication, Prussia was instrumental in uniting the German states, laying foundations for a unified Germany. But how did this kingdom, with its roots in Baltic territories, achieve such prominence, and why does its complex history continue to evoke admiration, debate, and occasional discomfort in Germany today?

What Was The Berlin Airlift? – Mythbusting Berlin

In the ruins of 1948, the silence of Berlin was not a sign of peace, but a held breath before a new catastrophe. The city, drowning in rubble and political intrigue, became the staging ground for the twentieth century’s most audacious gamble. While popular history remembers the chocolate parachutes and smiling pilots, the reality of the Berlin Airlift was a terrifying operational nightmare born from a ruthless currency war. It wasn’t just a humanitarian mission;

What Was The Socialist Kiss? – Mythbusting Berlin

It is one of the most curious and enduring images of the Cold War: two middle-aged, grey-suited men, locked in a fervent embrace, their lips pressed together in a kiss of apparent revolutionary passion. This was the ‘Socialist Fraternal Kiss’, a ritual that, for a time, seemed to encapsulate the unwavering solidarity of the Eastern Bloc.

But what was behind this seemingly intimate gesture? Was it a genuine expression of camaraderie, a piece of

Who Built The Berlin Wall? – Mythbusting Berlin

One of the most common questions I have encountered from people curious about Berlin, and often so cryptically phrased. Who built the Berlin Wall? A simple five-word query, yet one that can be read one of two ways. More than thirty years since the ‘Fall of the Wall’, the story of its construction continues to baffle many who are mainly familiar with its existence through knowledge of its importance…

Who Really Raised The Soviet Flag On The Reichstag? – Mythbusting Berlin

One iconic photograph has come to symbolise the Red Army’s victory over Nazi Germany in 1945—the Soviet flag waving triumphantly above Berlin’s battered Reichstag building. Yet behind this enduring image lies controversy, confusion, and political manipulation. Who truly raised the Soviet banner atop the Reichstag? Was it a spontaneous act of heroism or carefully staged Soviet propaganda? Decades later, unraveling the truth reveals surprising layers beneath the mythologized symbol of Soviet triumph.

Who Was Really Responsible For The Reichstag Fire? – Mythbusting Berlin

Various theories have been posited as to who actually set fire to the German parliament in 1933. Was it the opening act in an attempted Communist coup or a calculated false flag operation carried out by elements of the Nazi Party, intended to create the conditions necessary for introducing single-party rule? And what part did the young man from Holland, arrested shirtless inside the building the night of the fire, play in this event?

Who Were The Last Nazis On Trial? – Mythbusting Berlin

More than eighty years after the Holocaust, courtrooms across Germany still echo with testimony from the final chapter of Nazi justice. Centenarian defendants in wheelchairs, their faces hidden behind folders, arrive to answer for crimes committed in their youth. These are not the architects of genocide—those men faced their reckoning at Nuremberg decades ago. These are the guards, the secretaries, the bookkeepers: ordinary people who enabled extraordinary evil. Their trials represent a legal revolution: the

Why Is Berlin The Capital Of Germany? – Mythbusting Berlin

There was little in its humble origins—as a twin trading outpost on a minor European river—to suggest that Berlin was destined for greatness. It sits on the flat expanse of the North European Plain, a landscape once dismissively referred to as the “sandbox of the Holy Roman Empire.” Unlike other world capitals, it lacks breathtaking scenery or a naturally defensible position. It is a city built not on majestic hills or a grand harbour, but