“In all areas we increasingly have the thing without its essence. We have beer without alcohol, meat without fat , coffee without caffeine – and even virtual sex without sex.”

Slavoj Žižek

Decaffeinated coffee is either a blessing for those who love the taste but not the tremors, or a tragic compromise—akin to sugar-free cake or an alcohol-free pint.

It exists, but in doing so, it negates its very essence.

It’s the kind of conundrum that brings to mind a joke from Ernst Lubitsch’s Ninotchka, where a customer orders coffee without cream, only for the waiter to reply: “I’m sorry, sir, we have no cream. But can I offer you coffee without milk?”

A certain kind of reverse-Hamlet. Thus spake the bonnie prince: “To not to be whilst being, that is the answer!”.

The success of certain regimes has hinged on the full-strength of particular beverages. The British Empire ran on sweet milky tea, Italy without espresso is unthinkable, and Spanish colonial South America was, and remains for many, fueled by yerba-maté. What we drink, much like what we buy, has always been tied to identity—particularly under capitalism, where consumer habits shape personal and national narratives.

But tea for British imperialists, espresso for fascists… and decaf for Nazis?

The idea that Hitler’s regime had something to do with the rise of decaf coffee has been whispered in closed circles for years. It’s the kind of claim that now thrives online, blending historical intrigue with the sinister allure of the Third Reich’s technological, medical, and military experiments. Given the Nazis’ notorious obsession with controlling bodily functions—through diet, drugs, and pseudo-scientific engineering—there may be some truth to it.

But here lies the paradox. A state obsessed with racial and ideological purity promoting a drink that has been stripped of its most defining quality? It seems contradictory. Then again, if anyone were to try to ‘purify’ coffee by removing its stimulant properties, it would be the Nazis.

–

From Goat Herders to Global Addiction

“The coffee must be black as the devil , hot as hell , pure as an angel and sweet as love.”

Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord

Coffee’s development from obscure regional beverage to global phenomenon begins in Ethiopia, where, according to legend, a 9th-century goat herder named Kaldi noticed his goats behaving erratically after munching on some red berries.

Unlike most historical origin stories, this one has a ring of truth—coffee cherries contain caffeine, a natural stimulant that can make animals (and humans) unusually energetic.

By the 15th century, coffee had made its way to the Arabian Peninsula, where Sufi mystics used it to stay awake during long nights of prayer.

In 1574, the first mention in Europe of coffee appeared in a European botany book. But for almost 100 years, it was of interest only to natural scientists and travelers to the Orient.

From there, it spread like wildfire. The Ottomans took it to Istanbul, the Venetians smuggled it into Europe, and by the 17th century, coffee houses were popping up across England, France, and the German states.

In its early years, coffee was often viewed with suspicion. Religious leaders in Mecca tried to ban it, labelling it an intoxicant. European clergy debated whether it was a “Christian drink” or a “Muslim vice”—until Pope Clement VIII allegedly took a sip and declared it “too delicious to be Satanic.” From then on, coffee’s rise was unstoppable.

By the 18th century, coffee plantations were springing up across the European colonies. European colonial powers like the Dutch, French, and British established coffee plantations in the Caribbean, South America, and Southeast Asia—to meet booming demand. The cultivation of coffee dramatically increased global trade, making coffee beans more accessible and affordable for a broader segment of society by the late 18th century.

Brazil, in particular, became the powerhouse of global production, and by the 19th century, coffee was a daily staple for millions. Becoming a regular part of daily routines, particularly among Europe’s burgeoning middle classes. Technological innovations, including improved roasting methods and mass-produced coffee grinders, contributed to coffee’s widespread domestic consumption.

By 1914 – the year the First World War started in Europe – Germany in particular accounted for one-third of worldwide coffee consumption, second only after the USA, which had 30 million more inhabitants.

Nowadays, around 80% of the world’s population – around 6.4 billion people – consumes caffeine – typically in the form of coffee, tea, or cola – with the average consumer’s daily intake being around 200 milligrams. Making caffeine the worldwide number one drug of choice. Decaf coffee makes up around 12% of total global coffee consumption – a number that is steadily growing year by year.

–

Vive Prussian Muckefuck

“It is disgusting to notice the increase in the quantity of coffee used by my subjects, and the amount of money that goes out of the country as a consequence. Everybody is using coffee; this must be prevented. His Majesty was brought up on beer, and so were both his ancestors and officers. Many battles have been fought and won by soldiers nourished on beer, and the King does not believe that coffee-drinking soldiers can be relied upon to endure hardships in case of another war.”

Frederick II of Prussia, 1777; quoted by Bert L. Vallée, Alcohol in the Western World, Scientific American, Vol. 278, No. 6 (June), 1998, pp. 80-85

If you were to walk through the cities of Berlin, Vienna, or Königsberg in the 18th or 19th century, the smell of roasting coffee beans would have been impossible to ignore. Coffee had taken root in German-speaking lands, but its journey was far from smooth.

In Prussia, coffee consumption became so popular that it irritated Frederick the Great. Concerned that beer was losing its status as the national beverage, he tried to discourage coffee drinking, even hiring 400 soldiers who had been invalided out of his army as official ‘coffee sniffers’ – to patrol the streets and sniff out illegal roasters. His efforts failed.

In 1766, he introduced a state monopoly on roasting coffee beans and implemented heavy taxes, making coffee consumption prohibitively expensive for ordinary citizens. These restrictive measures led to widespread smuggling, illegal roasting, and secretive coffee gatherings in homes, illustrating Prussians’ persistent affection for the beverage.

The rise of Muckefuck is closely connected with Frederick the Great’s attempts in the mid-1700s to restrict coffee imports. Prussians chose to find creative solutions to satisfy their desire for caffeination, leading to widespread home production of coffee substitutes. As authentic coffee became a luxury reserved for the wealthy, Prussians of modest means turned to Muckefuck, a beverage that offered similar bitterness and warmth at a fraction of the cost.

The name Muckefuck likely originates from the French phrase mocca faux, meaning “fake coffee,” humorously adapted into local dialect. The Duden dictionary cites the olloquial use of “Muckefuck” as “thin coffee” in Rhenish-Westphalia as its origin. Derived from the Rhenish “Mucken” for brown wood, “mulm, ” and the Rhenish ” fuck” for lazy.

Another suggestion is that the term itself did not arrive until 1870 during the Franco-Prussian War again Napoleon III or even during the post-WWI French occupation of the Rhineland.

Regardless of the provenance of the term, this ersatz coffee provided a practical alternative during periods of economic hardship, war, or trade embargoes when coffee beans were heavily taxed or unavailable.

Common ingredients in Mukkefukk included:

- Chicory root, which provided a slightly bitter flavor

- Barley and rye, roasted to mimic the dark color of coffee

- Acorns and beets, used in extreme shortages to create a coarse, bitter brew

Vienna, meanwhile, embraced coffee wholeheartedly in the 1700s. The Austrians had supposedly ‘discovered’ coffee after the 1683 Siege of Vienna, when the retreating Ottoman army left behind sacks of beans. The city’s coffee houses became legendary, hosting everyone from Mozart to Freud.

By the late 19th century, Berlin – no longer just the capital of Prussia but now the capital of the unified German state – had finally developed its own coffee culture, as German scientists were also starting to tinker with the chemistry of coffee itself.

In order to create a truly decaffeinated coffee, it would first be necessary to better understand the presence of caffeine within the beans – and how to extract it.

The first person to extract caffeine from coffee beans was German chemist Friedlieb Ferdinand Runge, who in 1819 isolated the active ingredient of the deadly nightshade plant Atropa belladonna – a toxic alkaloid today known as atropine. During the Renaissance, women dripped extract of deadly night shade into their eyes to dilate their pupils and achieve a fashionable doe-eyed look – hence the name belladonna, meaning “beautiful woman.”

Runge determined that atropine was responsible for this dilating effect, testing the compound on the eyes of cats. This research soon came to the attention of German poet and polymath Wolfgang von Goethe, who, having just received a shipment of coffee beans, asked Runge if he could isolate the active stimulant compound. Runge obliged, and in 1820 succeeded in extracting and identifying caffeine.

However, this is where his research on the matter ended; he did not further investigate the chemistry of caffeine nor seek to use his extraction process commercially to produce decaffeinated coffee.

That breakthrough would have to wait nearly a century.

–

Decaffeination & The Roselius Process

“Coffee was only a way of stealing time that should by rights belong to your slightly older self.”

Terry Pratchett

Like many scientific discoveries, the road to decaffeinated coffee happened upon by chance, and then improved over time.

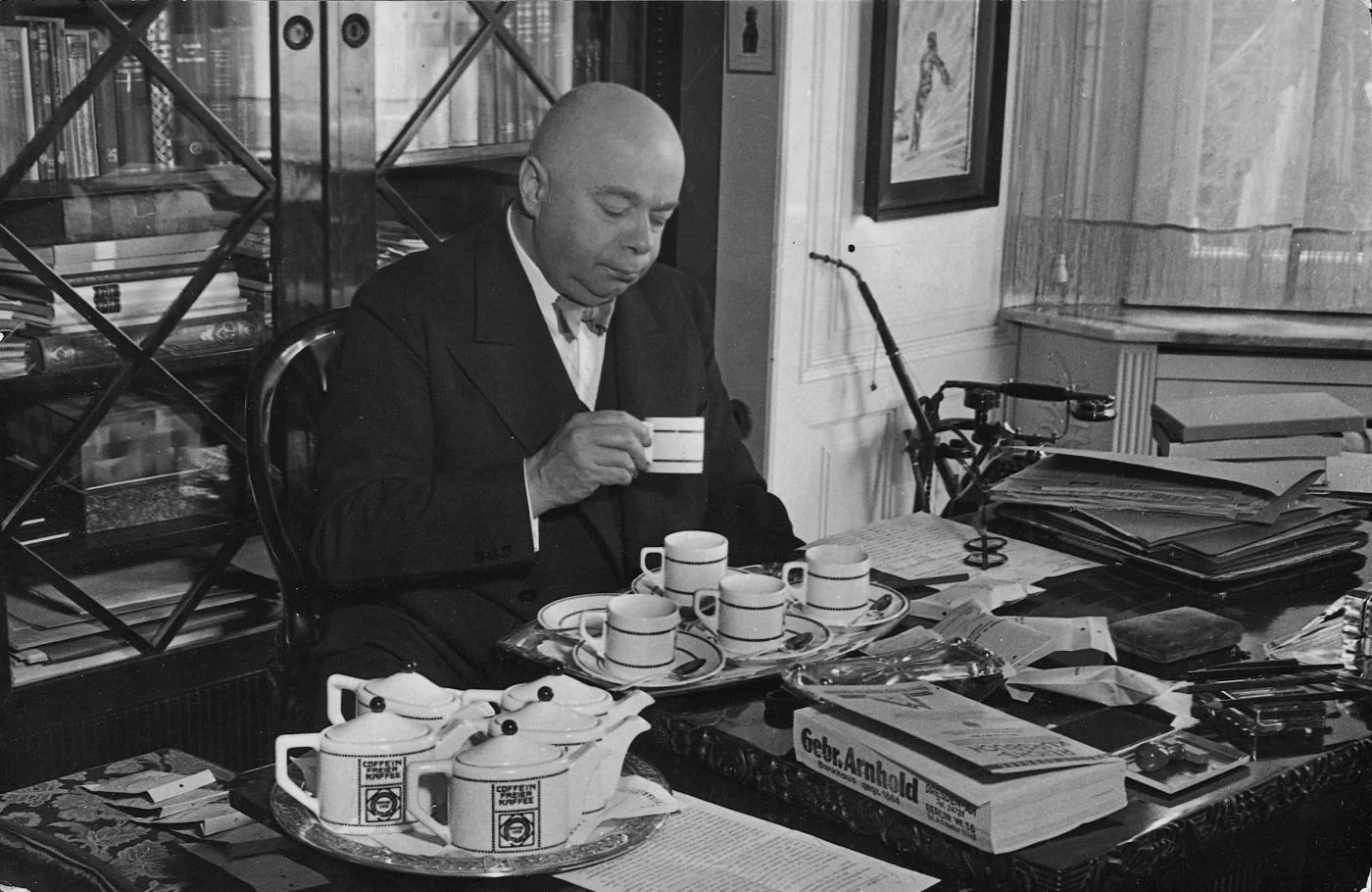

The process to remove caffeine from coffee beans was first discovered by the German merchant, patron of the arts, and Nazi sympathizer, Ludwig Roselius.

Ludwig Roselius wasn’t a Nazi, but his company, Kaffee HAG, continued operating under the Third Reich. His method for removing caffeine—using benzene, a chemical now known to be carcinogenic—was the first commercial decaffeination process. It was developed in the early 20th century, long before Hitler came to power.

So, as the story goes, in 1903 Roselius purchased a large amount of beans from Latin America which were shipped across the ocean by cargo ship to his warehouse in Germany. During the voyage, the ship was battered by turbulent waters and the cargo hold took on sea water. When the ship arrived the coffee beans had been completely soaked in salt water.

Roselius, not wanting to lose the shipment of “ruined” beans, asked his team of researchers to analyze the beans and see if they could be salvaged. The team conducted a series of taste tests and found that the seawater had removed much of the caffeine without losing much of the flavor. The resulting coffee was quite salty from the seawater but otherwise tasted similar to regular coffee.

They refined the process with chemicals and The Roselius Process was born.

This involved steaming green, unroasted coffee beans with ammonia-laced water until they became saturated with water and swelled to double their original size. The beans were then washed with an organic solvent like benzene or chloroform, which dissolved and flushed out the caffeine. Finally, the now-decaffeinated beans were dried and packaged for shipment to roasters and distributors.

Alternatively, the official story is that rather than being an accident, Roselius attributed his father’s death in 1902 to drinking too much coffee, so he invented decaf to save other addicts.

In 1906, Roselius founded the company Kaffee Handels-Aktiengesellschaft or Coffee Public Trading Company – better known as Kaffee HAG. Roselius’s decaffeinated coffee beans would soon be sold across Europe under the brand name Sanka – a contraction of the French sans caféine – and in the United States as Dekafa. Marketed as the first ever offering of decaffeinated coffee.

The Kaffee Hag company expanded its operations throughout the world at a very fast pace, and in 1914, Roselius established the U.S. headquarters in New York.

Three years later, Kaffee Hag in the United States was confiscated by the Office of Alien Property Custodian in 1917 because it was considered an enemy property.

By which time, Sanka would start appearing in the US with its distinctive orange packaging.

Sanka’s appeal worldwide lay not only in its exclusivility but also in its status as a luxury product, costing three times as much as regular coffee.

Other, less carcinogenic processes have since been created, most of which use chemicals, but the most natural and chemical-free process is the Swiss Water Process – relying on a combination of water, temperature, and time to gently remove caffeine while keeping the coffee’s flavour intact.

And this is where the Nazis enter the picture. Well, kind of.

–

The Reich Stuff

“Coffee, which makes the politician wise

And see through all things with his half-shut eyes…”

Alexander Pope, The Rape of the Lock

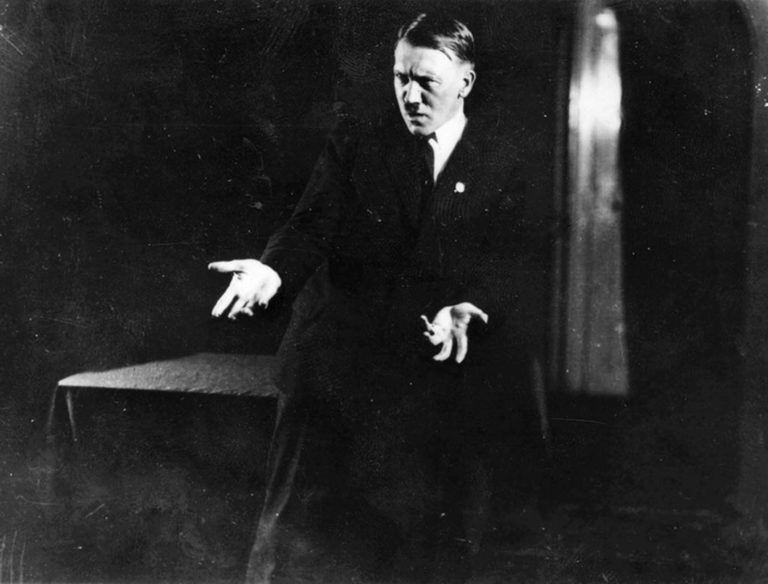

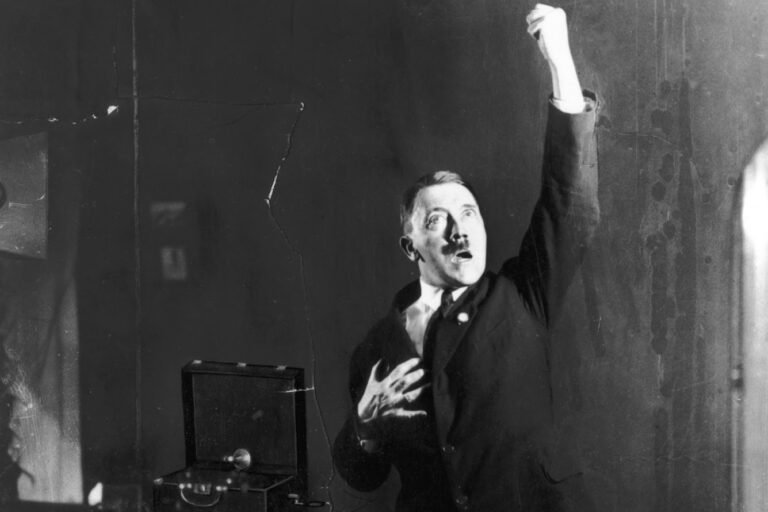

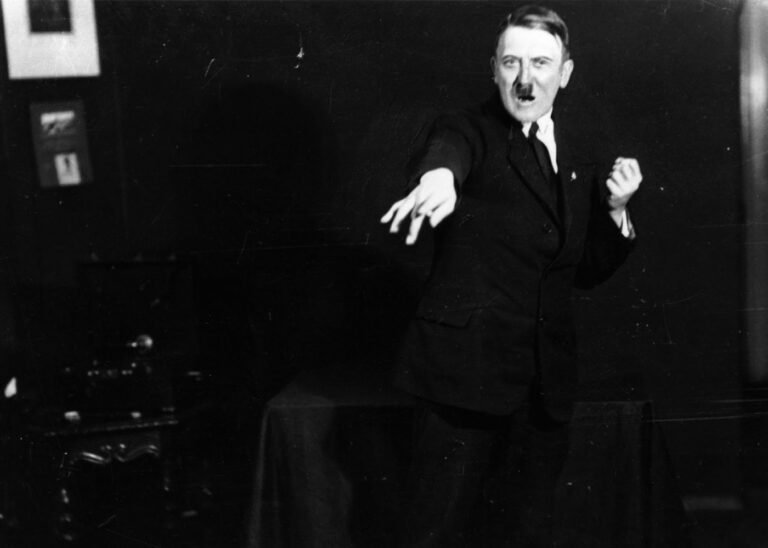

The Nazis’ real drug of choice wasn’t caffeine but methamphetamine—marketed under the brand name Pervitin.

German soldiers swallowed these pills by the handful, staying awake for days as they steamrolled through Poland and France. The Wehrmacht’s blitzkrieg tactics owed much to this pharmaceutical boost; though the subsequent paranoia, aggression, and psychotic breakdowns were an unfortunate side effect.

Yet, despite fuelling their war machine with stimulants, the Nazi leadership espoused a “clean and pure” lifestyle. Alcohol and tobacco were frowned upon, at least in official rhetoric. Adolf Hitler, famously abstinent from alcohol, took a hard stance against smoking, even introducing anti-tobacco campaigns long before they were fashionable.

Hitler himself wasn’t much of a coffee drinker—at least, not at first. His beverage preferences were famously tame: apple juice, sparkling water (Apollinaris and Pachinger), and the occasional alcohol-free beer from Munich’s Holzkirchen brewery. Yet, British intelligence concluded that he drank copious amounts of coffee during the war, perhaps in a bid to keep up with his erratic and increasingly drug-fuelled schedule.

Before the war, Hitler’s preferred stimulant was tea, which he took Russian-style—black, with lemon, and no milk — according to the writer, Jean Merrill du Cane, who interviewed Hitler in 1938 for an article published in the Australian Nambour Chronicle. Given his deep admiration for Mussolini, perhaps he shared Il Duce’s belief that coffee was an unnecessary luxury, a distraction from the rigours of national struggle.

For ordinary Germans, coffee was a vital part of daily life.

In 1933, Joseph Goebbels noted that Germany imported 2.16 million sacks of coffee annually, a figure that swelled to 3.29 million by 1938. But as the Nazis pursued economic self-sufficiency (autarky), the coffee trade was squeezed.

When Hermann Göring introduced the Four Year Plan in 1936 – a series of economic measures intended to prepare Germany for war – he spoke in terms of “guns before butter”, declaring that “guns will make us powerful; butter will only make us fat”.

Consumer goods and luxury items like coffee would be sacrificed at the altar of war.

By the early 1940s, real coffee was increasingly scarce. A pound of roasted coffee, which had cost 1.80 Reichsmarks in the early 1930s, shot up to an eye-watering 40 RM.

Mukkefukke made a grim return and the state produced Kaffee-Surrogat-Extrakt (Coffee Surrogate Extract) entered production.

The regime used its propaganda machine to frame coffee shortages as a patriotic sacrifice. After all, Hitler had declared that National Socialism and Fascism rejected a “comfortable and pleasant life.” If the people could tolerate Eintopf Sonntag (a monthly “one-pot meal” day where families ate leftovers to save money for state charities), surely they could stomach a lack of coffee.

Officially, the Nazi leadership took an ambivalent stance on the coffee. Some health officials condemned caffeine, particularly for women and young people. But there was no outright ban. Instead, Nazi propaganda subtly nudged the public towards German-made substitutes, portraying them as a patriotic alternative to foreign imports.

The real beneficiary of this policy was decaffeinated coffee, which became less or an expensive alternative and more of an alternative for the ideologically inclined.

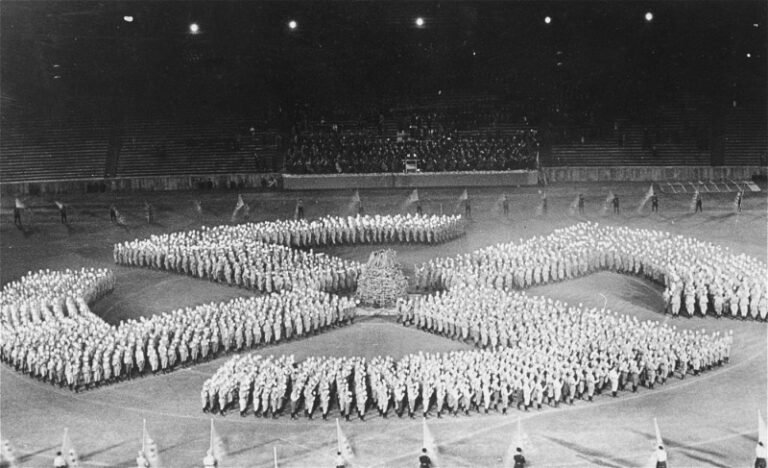

Ludwig Roselius, the Bremen-based coffee merchant who had invented the first commercial decaf coffee in the early 1900s was one of the chief beneficiaries of this policy. His company, Kaffee HAG, flourished under the Nazis. At the 1937 Reichsausstellung Schaffendes Volk festival, over a dozen cantinas served Kaffee HAG. At the 1936 Nuremberg Rally, the company provided Kaba, a chocolate milk drink, to more than 42,000 members of the Hitler Youth.

Roselius, however, was already so sufficiently successful before the Nazi takeover that in 1925 he also became the Chairman of Focke-Wulf Flugzeugbau, a position he would hand over to his brother in 1933, with the family retaining 46% control as the majority shareholders.

The Roselius family benefit from increased sales of Sanka decaf and also provide the war machines that would enable the Nazi conquests.

Focke-Wulf would build the first fully controllable helicopter, piloted by Nazi aviatrix Hanna Reitsch; the four-engined Fw 200 airliner that became the first plane to fly nonstop between Berlin and New York City on August 10, 1938; and the Fw 190 – the mainstay single-seat fighter for the Luftwaffe during World War II.

When Roselius died in 1943 it was at the end of a nine month stint in the luxury of the same Berlin hotel, the Kaiserhof, that Adolf Hitler had used as his pre-takeover headquarters.

Did this make Roselius a Nazi? Not quite. He had applied to join the party twice but was rejected—not because he opposed Nazi ideology, but because of his involvement in modernist art, which the regime labelled “degenerate.” He later fell out with Hitler over racial theories, advocating for a “purebred Lower German race” (geographical, not hierarchical) which didn’t align with the Nazi racial hierarchy.

While Roselius was neither a card-carrying Nazi – nor much of a Nazi sympathiser in his later life – his process for decaffeinating coffee was discovered way back in 1906. Before Adolf Hitler had even arrived in Vienna, nevermind served in the Germany Army, fought in the First World War, and encountered the German Workers Party in its infancy.

To attribute the development or even the popularisation of decaf coffee to the Nazi Party would be simply erroneous.

One year after Roselius’ death, even the most indescribable ersatz coffee was running out. The German economy, stretched by war and Allied blockades, could no longer support even the illusion of a caffeine fix. Coffee had gone from a symbol of economic prosperity under the early Nazi years to yet another casualty of war.

And as the Third Reich collapsed, so too did its coffee policies. In the post-war years, real coffee flooded back into Germany, along with American cigarettes and jazz records. The Nazis had tried to control consumer habits, dictate what Germans drank, and replace coffee with ersatz alternatives.

But in the end, even the Führer couldn’t stamp out the need for a decent cup of coffee.

**

Conclusion

No

Decaf was invented far before the Nazi Party takeover by Bremen coffee merchant Ludwig Roselius.

***

If you’ve enjoyed reading this article, consider booking one of our private guided tours of Berlin.

HISTORICAL ARTICLES

Mythbusting Berlin

Are There Any Nazi Statues Left In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

Visitors to Berlin often arrive expecting to find the physical remnants of the tyranny of the 20th century still standing – statues of dictators, triumphal arches, or bronze idols. Instead, they often find none. The stone symbols and statues of the Third Reich are still gazing down on them, however, hiding in plain sight. But why are there no statues of Hitler? Did the Allies destroy them all in 1945, or is the truth stranger

Could The Western Allies Have Captured Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

To contemplate a Western Allied capture of Berlin in 1945 is to challenge the established endgame of the Second World War. What was the true military and logistical feasibility of a Western Allied assault on the Nazi capital? What factors truly sealed Berlin’s fate, and what might have changed had the Allies pushed eastward?

Answering these questions means delving into the complex interplay of logistics, political maneuvering, and the competing visions for a post-war world

Did Any Of The Rothschild Dynasty Die In The Holocaust? – Mythbusting Berlin

The Rothschild name is synonymous with immense wealth, influence, and persistent conspiracy theories—especially during the era of Nazi Germany. Often targeted by antisemitic propaganda, the family’s survival during World War II has sparked myths about their supposed immunity from Nazi persecution. But did any Rothschild family member actually perish in the Holocaust? This article explores that compelling question, unraveling historical misconceptions and revealing the reality behind one of Europe’s most famous dynasties.

Did Frederick The Great Introduce The Potato To Germany? – Mythbusting Berlin

One of the more bizarre claims to fame attributed to the first King of Prussia is that the man who would go down in history known as Frederick the Great introduced the potato to Germany during his reign back in the 1700s. This starchy root vegetable has undoubtedly become a staple part of German cuisine – an essential addition to any plate of Schnitzel, Schweinshaxn, and Königsberger Klopse – however, whether Frederick the Great is

Did Hitler Escape To Argentina In 1945? – Mythbusting Berlin

Although Nazi leader, Adolf Hitler, certainly remains an inescapable figure, could there be any truth to the story of his escape to Argentina in 1945? That the most wanted man on earth could simply vanish, to spend the rest of his life peacefully in South American obscurity captivates imaginations. Yet, despite numerous investigations, this tale persists primarily as myth—fueled by speculation, hearsay, and conspiracy theories.

Did Hugo Boss Design The Nazi Uniforms? – Mythbusting Berlin

The idea that Hugo Boss – the man whose name now adorns expensive suits and fragrances – was the creative genius behind the Nazi uniforms suggests a terrifying collision of haute couture and holocaust – a marriage of high style and high crimes. The image is striking: a German tailor sketching the ultimate villain’s costume. But history, as usual, is far messier, more bureaucratic, and more banal than the internet memes suggest. To understand who

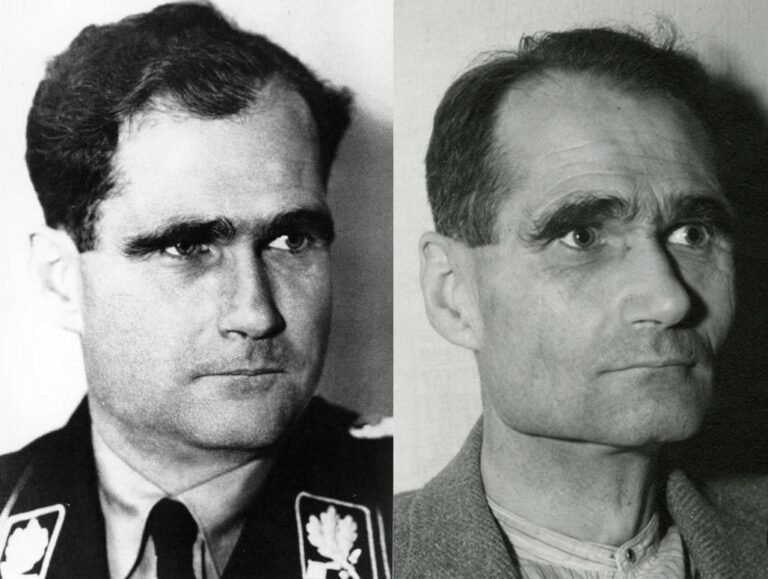

Did Rudolf Hess Really Commit Suicide? – Mythbusting Berlin

On a summer’s day in 1987, the last Nazi war criminal of the Nuremberg trials was found dead in a prison built for hundreds, yet for two decades, housed only him. The official verdict was suicide, a straightforward end to a life defined by fanaticism, delusion, and contradiction.

But the simplicity of the report belied the complexity of the man and the 46 years he had spent in Allied custody. In the meticulously controlled

Did The Nazis Develop Nuclear Weapons? – Mythbusting Berlin

The Nazi obsession with super-weapons became so serious in the closing stages of the Second World that Adolf Hitler personally believed that such ‘Wunderwaffen’ both existed in a usable form – and would save the country from defeat. Had the Nazis managed to develop nuclear weapons by 1945 – the outcome of the war would surely have been different. But how close were Hitler, Himmler, and his henchmen to developing an A-bomb?

Did The Nazis Invent Decaf Coffee? – Mythbusting Berlin

Persistent rumors claim that Nazis preferred their coffee anything but pure, leading some to wonder if they might have influenced the development of decaffeinated coffee. Although decaf was already widely available across Europe by the mid-20th century, speculation continues: could the Nazis really have played a role in popularizing—or even discovering—this caffeine-free alternative, or is this simply another caffeinated conspiracy cooked up to sensationalize an ordinary historical detail?

Did The Nazis Invent The Bicycle Reflector? – Mythbusting Berlin

The fruits of wartime ingenuity are plenty – so many, in-fact, that it has become somewhat of a worn cliche that as the guns start firing the innovators get to work, often solving problems while providing more problems for the enemy to overcome.The kind of progress that results in the production of newer improved, more lethal weapons, such as to increase the chances of victory.

Did The Nazis Run The Largest Counterfeiting Operation In History? – Mythbusting Berlin

During the Second World War the Nazis masterminded an astonishing plot to destabilise Britain by flooding its economy with counterfeit banknotes. Crafted in secret by concentration camp prisoners, this forged fortune became the most ambitious counterfeiting operation ever attempted. But was it history’s largest? Dive into the extraordinary tale of Operation Bernhard,

rife with deception, survival, and intrigue—revealing the truth behind one of the Third Reich’s most audacious schemes and its surprising legacy.

Did The Second World War End In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

When is a war ever truly over? When the last shot is fired in anger would seem like the best measure. Rarely, though, is it possible to gain insight into such a moment.

Remarkably, a record still exists of such a moment at the end of the First World War on the Western Front. A seismic register and recording of the last belching battery of British guns firing artillery across no-man’s-land, followed by a profound

Did The Spanish Flu Pandemic Help The Nazis Take Power? – Mythbusting Berlin

The devastating Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918-1919 struck amid Germany’s post-war turmoil, compounding social instability, economic hardship, and widespread political disillusionment. Could this catastrophic health crisis have indirectly paved the way for Nazi ascension? While often overshadowed by war and revolution, the pandemic’s profound psychological and societal impacts arguably contributed to the perfect storm, enabling extremist ideologies—including Nazism—to gain popularity and ultimately seize power in a fractured Germany.

Have Adolf Hitler’s Remains Been DNA Tested? – Mythbusting Berlin

In the smouldering ruins of Berlin in 1945, the world’s most wanted man vanished. Did Adolf Hitler, as official history attests, die by his own hand in the Führerbunker? Or did he escape, fuelling a thousand conspiracy theories that have echoed for decades? For years, the Soviets claimed to hold the gruesome proof of his death: a skull fragment and a set of teeth, locked away in Moscow archives. But in an age of definitive

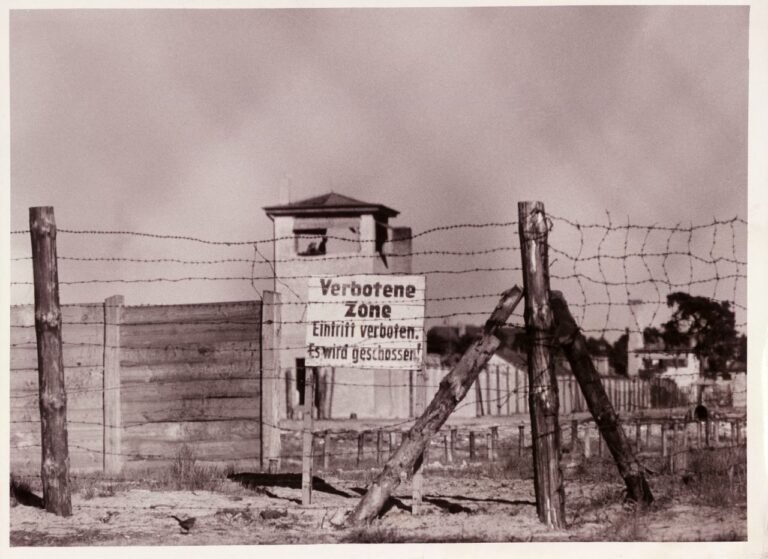

How Did The Nazi Concentration Camps Differ From The Soviet GULAG?

The Nazi concentration camps and Soviet Gulag system have often been conflated in popular imagination—twin symbols of twentieth-century totalitarian horror. Yet the two systems operated on fundamentally different principles. One extracted labor to fuel industrialisation while accepting mass death as collateral damage; the other evolved into purpose-built machinery of genocide. Understanding these distinctions isn’t merely academic—it reveals how different ideologies produce different atrocities, and why Germany and Russia reckon with these legacies so differently today.

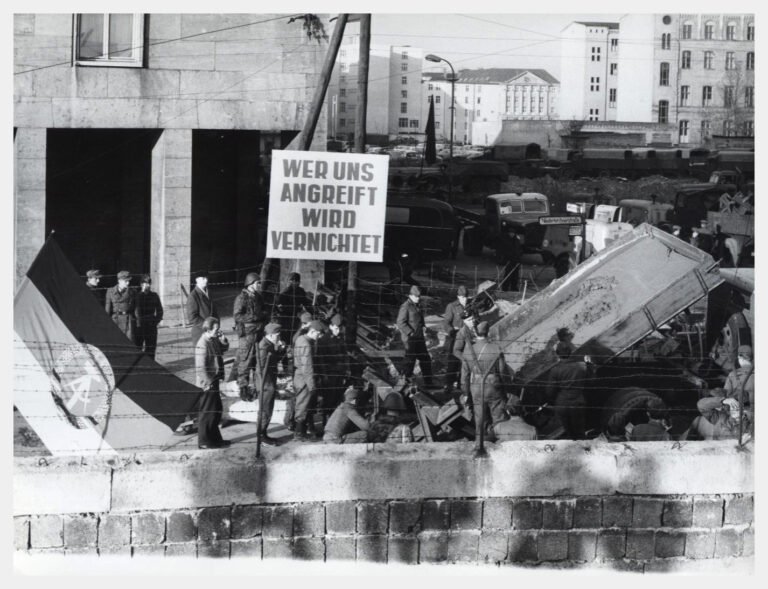

How Long Did It Take To Build The Berlin Wall? – Mythbusting Berlin

It is one of the most enduring images of the 20th century: a city divided overnight. The popular narrative tells us that Berliners went to sleep in a unified city and woke up in a prison. While the shock of August 13th 1961, was very real, the idea that the ‘Wall’ appeared instantly is a historical illusion. The physical scar that bisected Berlin was not a static creation, but a living, malevolent beast that evolved

How Many Assassination Attempts On Adolf Hitler Were There? – Mythbusting Berlin

Nazi leader, Adolf Hitler, projected an aura of invincibility, a man of destiny shielded by providence. But behind the carefully constructed image of the untouchable Führer lies a story of constant threat, of bombs that failed to detonate, and errant bullets that missed their mark. Unearth the hidden history of the numerous attempts on Hitler’s life as we explore the courage of those who tried to change the course of history and the devil’s luck

How Many Jews Died In The Holocaust? – Mythbusting Berlin

The answer to the question posed of how many Jews died in the Holocaust is a simple one: too many. That merely one death was an unforgivable obscenity is a fundamental and necessary realisation in understanding the capriciousness of this unparalleled racial genocide. To comprehend, however, the full number of Jews murdered in Europe by the Nazi regime in the 1930s and 1940s is a detective story of epic proportions: the evidence overwhelming, multifaceted, and

How Many People Died Trying To Escape East Germany? – Mythbusting Berlin

The image of the Berlin Wall is seared into our collective memory, a concrete symbol of Cold War oppression. We think of the daring escapes and the tragic deaths of those who failed. But that well-known number is only a fraction of the truth. The story of those who died trying to escape East Germany is far broader and more complex than most imagine, stretching along a thousand-kilometer border and out into the cold waters

How Old Is Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

A relatively new arrival in Europe, Berlin is over 1000 years younger than London, nevermind Rome or Athens, Jerusalem or Jericho. Just how old is Berlin though?

A question fraught with false assumptions and distortions – that has more often than not been answered with propaganda as it has with the cold hard truth.

Was Adolf Hitler A Drug Addict? – Mythbusting Berlin

Solving the enigma of the ‘Führer’ has become a preoccupation for many, since the arrival of the Austrian-German onto the world stage – although moving beyond the mythology without falling into the trap of prejudically extrapolating on the psychopathography of Hitler or demonising so as to excuse his actions has proven problematic. What to make of the man who became more than the sum of his masks? The painter; the military dilettante, the mass murderer,

Was Adolf Hitler A Freemason? – Mythbusting Berlin

History abhors a vacuum, but adores a mystery. Such is the speculative fiction suggesting a secret allegiance behind the rise of the Third Reich – that the catastrophe of the Second World War was orchestrated from the shadows of a Masonic lodge. The image of Adolf Hitler—the drifter from Vienna turned dictator—as a covert initiate of the very brotherhood he publicly reviled, however, creates a paradox that collapses under scrutiny. As when we unlock the

Was Adolf Hitler Gay? – Mythbusting Berlin

In the shadowy corridors of Third Reich history, few questions provoke as much tabloid curiosity and scholarly exasperation as the sexuality of Adolf Hitler. For decades, rumors have swirled—whispered by political enemies in 1930s Munich, psychoanalyzed by American spies in the 1940s, and sensationalized by revisionist authors today. Was the dictator who condemned thousands of men to concentration camps for “deviant” behavior hiding a secret of his own? By peeling back the layers of propaganda,

Was Adolf Hitler Jewish? – Mythbusting Berlin

Was the dictator who orchestrated the murder of millions of European Jews secretly one of them? It is perhaps the darkest irony imaginable, a story whispered for decades in backrooms, bars, and conspiracy forums alike. The most-common rumour – the ‘Frankenberger Myth’ – suggests that Adolf Hitler’s paternal grandfather was Jewish, a secret so damaging it could have unraveled the entire Nazi regime. But where does this claim come from? And, more importantly, is there

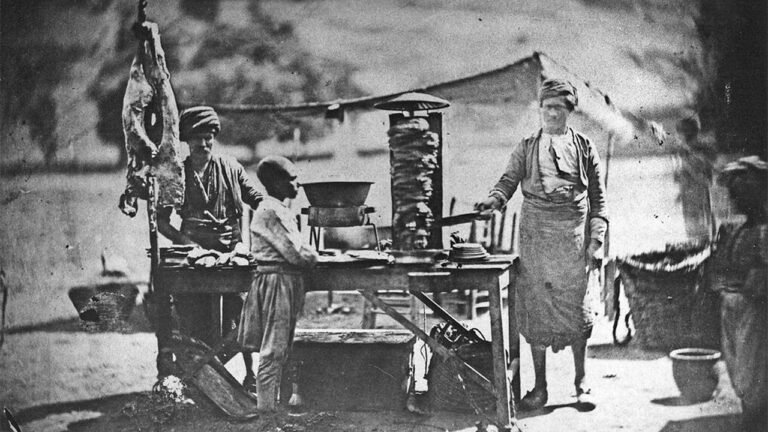

Was Currywurst Invented In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

Explore the story behind what many consider Berlin’s most iconic snack—the ever-so-humble Currywurst. Often hailed as an enduring symbol of culinary creativity amid Cold War scarcity, this humble dish has inspired fierce debate about its true origin. But was it genuinely invented here in Berlin, or have proud locals simply adopted and elevated this spicy street-food favorite into legendary status all their own?

Was Fanta Invented By The Nazis? – Mythbusting Berlin

As one of the most secretive organisations in the world, the Coca Cola corporation refuses to share its secret recipe with anyone. Famously insisting only on shipping the base syrup of its drinks to plants around the world to be carbonated and distributed.

This combined with the trade limitations of the Second World War may have led to the introduction of one of the most popular soft-drinks in the world. But could it be true:

Was Frederick The Great Gay? – Mythbusting Berlin

Frederick II of Prussia, better known as Frederick the Great, is often remembered as the archetypal enlightened monarch – a brilliant military commander, patron of the arts, and learned philosopher. Yet behind the stern portraits of this 18th-century warrior-king lies a personal life long shrouded in intrigue and speculation. Intrigue around the king’s sexual orientation has persisted through the centuries, chiefly revolving around one question: Was Frederick the Great gay?

Was Henry Ford A Nazi? – Mythbusting Berlin

US auto tycoon, Henry Ford, holds the ignominious distinction of being the only American Adolf Hitler praised by name in his National Socialist manifesto: ‘Mein Kampf’. This was not, as it turns out, the only connection between Ford and the Party of Hitler, Himmler, and the Holocaust.

Ford’s overt affinity with the Third Reich reveals a troubling past. How deep these connections ran, and how consequential they were for both sides, is a chapter

Was The Colour Blue Invented In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

Tracing the true history of blue—from ancient Egyptian dyes to the accidental discovery of Prussian Blue in a Berlin lab. We’ll debunk myths about seeing blue, explore colonial indigo plantations, scale mountains with a cyanometer, and trace Van Gogh’s starry skies—all to answer one question: how did Berlin shape our understanding of the world’s rarest color?

Was The Döner Kebab Invented In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

Unlikely icon of immigrant success; fast food symbol of the working class; over-hyped midnight disco eat; or culturally appropriated cuisine? Its influence goes far beyond layers of seasoned meat and fresh vegetables stuffed into pita bread. But does Berlin deserve credit as the Döner Kebab’s true birthplace, or has the city merely refined and popularized a culinary tradition imported from elsewhere?

Was The Fall Of The Berlin Wall An Accident? – Mythbusting Berlin

On a seasonally crisp night in November 1989, one of the most astonishing events of the 20th century occurred. After twenty eight years, three months, and twenty eight days of defining and dividing the German capital, the Berlin Wall ceased to exist – at least in an abstract sense. Although the removal of this symbol of the failure of the East German system would take some time, its purpose – as a border fortification erected

Was The Nazi Party Democratically Elected? – Mythbusting Berlin

The myth persists that Adolf Hitler rose to power through popular democratic choice. Yet history reveals a darker, more complicated truth. Hitler’s ascent involved exploiting democratic institutions, orchestrating violence, propaganda, and political intrigue—not a simple election victory. Understanding how Germany’s democracy collapsed into dictatorship helps illuminate the dangerous interplay between public desperation, elite miscalculations, and extremist ambition, providing crucial lessons for safeguarding democracy today.

Were The Allied Bombings Of Germany War Crimes? – Mythbusting Berlin

The history of the Allied bombing of Germany during the Second World War still triggers fierce debate. Was reducing cities to rubble a necessary evil – justice from above in a just war – or an unforgivable crime? Can the intentional targeting of civilians ever be justified as militarily necessary?

In a conflict where all rules seemed to vanish, an even more pertinent question persists: by the very standards they would use to judge their

Were The Nazi Medical Experiments Useful? – Mythbusting Berlin

Before the Nazi period, German medicine was considered the envy of the world – a shining monument to progress. But deep within that monument, a rot was spreading, one which would collapse the entire structure into an abattoir. From the wreckage, we are left with a profoundly uncomfortable inheritance: a moral enigma wrapped in doctor’s whites.

What to make of the data, the images, and the terrible knowledge gleaned from unimaginable human suffering. Whether

What Are The Origins Of The Nazi Salute? – Mythbusting Berlin

A specter is haunting the modern mind, a gesture so charged with the dark electricity of history that its mere depiction can unleash a storm of controversy.

It is a simple movement: the right arm, stiff and straight, raised to the sky. But in that simplicity lies a terrifying power, a symbol of a regime that plunged the world into an abyss and a chilling reminder of humanity’s capacity for organised hatred.

This

What Are The Origins Of The Nazi Swastika? – Mythbusting Berlin

Long before the legions of the Third Reich marched beneath its stark, unnerving geometry, the swastika lived a thousand different lives. It was a symbol of breathtaking antiquity, a globetrotting emblem of hope and good fortune that found a home in the most disparate of cultures. To even begin to understand its dark 20th-century incarnation, one must first journey back, not centuries, but millennia.

What Are The Pink Pipes In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

A first-time visitor to Berlin could be forgiven for thinking the city is in the midst of a bizarre art installation. Bright pink pipes, thick as an elephant’s leg, climb out of the ground, snake over pavements, arch across roads, and disappear back into the earth. Are they part of a complex gas network? A postmodern artistic statement? A whimsical navigation system? These theories, all logical, are all wrong. The truth is far more elemental,

What Do The Colours Of The German Flag Symbolise? – Mythbusting Berlin

What does a flag mean? Is it merely a coloured cloth, or does it hold the hopes, struggles, and identity of a nation? The German flag, with its bold stripes of black, red, and gold, is instantly recognisable. But the story of its colours is a tumultuous journey through revolution, suppression, and reinvention. The common explanation for their symbolism is a simple, romantic verse, yet the truth is a far more complex and contested tale,

What Happened To Adolf Hitler’s Alligator? – Mythbusting Berlin

It is often said that you can tell a lot about a person by their relationship with animals; that owners often come to look and behave like their pets. Or is it perhaps more that people choose their pets to correspond to their personality? Nazi leader Adolf Hitler’s love of dogs, for example, is well documented but what is there to make of his relationship with reptiles?

What Happenened To The German Royal Family? – Mythbusting Berlin

When the smoke cleared over the trenches in November 1918, the German Empire had evaporated, and with it, the divine right of the Hohenzollern dynasty. Conventional wisdom suggests the family simply vanished into the sepia-toned obscurity of history books—exiled, forgotten, and irrelevant. But dynasties, like weeds in a landscaped garden, are notoriously difficult to uproot entirely. The story of the German royals did not end with the Kaiser’s flight to Holland; it merely shifted gears.

What Is The Difference Between Fascism & Nazism? – Mythbusting Berlin

While the terms ‘Fascist’ and ‘Nazi’ are often bandied around interchangeably as shorthand for tyranny – Italian fascism and German National Socialism were distinctly different beasts. Albeit ideological kin. One an ideology of state-worship, born from post-war chaos and national pride; the other built upon a fanatical, pseudo-scientific obsession with race. Two peas in the same totalitarian pod – twins in tyranny – more succinctly summarised as the Nazi chicken to the Fascist egg.

What Was Checkpoint Charlie? – Mythbusting Berlin

Checkpoint Charlie remains among Berlin’s most visited historical sites, famed worldwide for its significance during the Cold War. Originally established as a modest border-crossing point, it evolved dramatically over the decades into an international symbol of freedom, espionage, and intrigue. Today, critics and locals often dismiss it as little more than a tourist trap—Berlin’s Disneyland—but how exactly did Checkpoint Charlie get its peculiar name, and what truths hide behind its popularity?

What Was Prussia? – Mythbusting Berlin

Prussia’s legacy is both remarkable and contentious—once a minor duchy, it rose dramatically to shape modern European history. Renowned for military discipline, administrative efficiency, and cultural sophistication, Prussia was instrumental in uniting the German states, laying foundations for a unified Germany. But how did this kingdom, with its roots in Baltic territories, achieve such prominence, and why does its complex history continue to evoke admiration, debate, and occasional discomfort in Germany today?

What Was The Berlin Airlift? – Mythbusting Berlin

In the ruins of 1948, the silence of Berlin was not a sign of peace, but a held breath before a new catastrophe. The city, drowning in rubble and political intrigue, became the staging ground for the twentieth century’s most audacious gamble. While popular history remembers the chocolate parachutes and smiling pilots, the reality of the Berlin Airlift was a terrifying operational nightmare born from a ruthless currency war. It wasn’t just a humanitarian mission;

What Was The Socialist Kiss? – Mythbusting Berlin

It is one of the most curious and enduring images of the Cold War: two middle-aged, grey-suited men, locked in a fervent embrace, their lips pressed together in a kiss of apparent revolutionary passion. This was the ‘Socialist Fraternal Kiss’, a ritual that, for a time, seemed to encapsulate the unwavering solidarity of the Eastern Bloc.

But what was behind this seemingly intimate gesture? Was it a genuine expression of camaraderie, a piece of

Who Built The Berlin Wall? – Mythbusting Berlin

One of the most common questions I have encountered from people curious about Berlin, and often so cryptically phrased. Who built the Berlin Wall? A simple five-word query, yet one that can be read one of two ways. More than thirty years since the ‘Fall of the Wall’, the story of its construction continues to baffle many who are mainly familiar with its existence through knowledge of its importance…

Who Really Raised The Soviet Flag On The Reichstag? – Mythbusting Berlin

One iconic photograph has come to symbolise the Red Army’s victory over Nazi Germany in 1945—the Soviet flag waving triumphantly above Berlin’s battered Reichstag building. Yet behind this enduring image lies controversy, confusion, and political manipulation. Who truly raised the Soviet banner atop the Reichstag? Was it a spontaneous act of heroism or carefully staged Soviet propaganda? Decades later, unraveling the truth reveals surprising layers beneath the mythologized symbol of Soviet triumph.

Who Was Really Responsible For The Reichstag Fire? – Mythbusting Berlin

Various theories have been posited as to who actually set fire to the German parliament in 1933. Was it the opening act in an attempted Communist coup or a calculated false flag operation carried out by elements of the Nazi Party, intended to create the conditions necessary for introducing single-party rule? And what part did the young man from Holland, arrested shirtless inside the building the night of the fire, play in this event?

Who Were The Last Nazis On Trial? – Mythbusting Berlin

More than eighty years after the Holocaust, courtrooms across Germany still echo with testimony from the final chapter of Nazi justice. Centenarian defendants in wheelchairs, their faces hidden behind folders, arrive to answer for crimes committed in their youth. These are not the architects of genocide—those men faced their reckoning at Nuremberg decades ago. These are the guards, the secretaries, the bookkeepers: ordinary people who enabled extraordinary evil. Their trials represent a legal revolution: the

Why Is Berlin The Capital Of Germany? – Mythbusting Berlin

There was little in its humble origins—as a twin trading outpost on a minor European river—to suggest that Berlin was destined for greatness. It sits on the flat expanse of the North European Plain, a landscape once dismissively referred to as the “sandbox of the Holy Roman Empire.” Unlike other world capitals, it lacks breathtaking scenery or a naturally defensible position. It is a city built not on majestic hills or a grand harbour, but