“If you have nothing to tell us except that one barbarian succeeded another on the banks of the Oxus and Jaxartes, what is that to us?”

Voltaire

Making any pronouncement on Berlin’s earliest history is a project fraught with frustration.

Pinpointing exactly when the settlement became a city, or the town turned into a strategic interest remains easier than identifying on which date the embers of civilisation and permanent habitation started to flicker.

Not least as the debate over Berlin’s provenance has been, and remains, a controversial issue. Like any aspect of this city’s problematic history, the political ramification of any specific conclusion exposes an inherent bias.

But how can what boils down to a simple matter of numbers be so problematic?

–

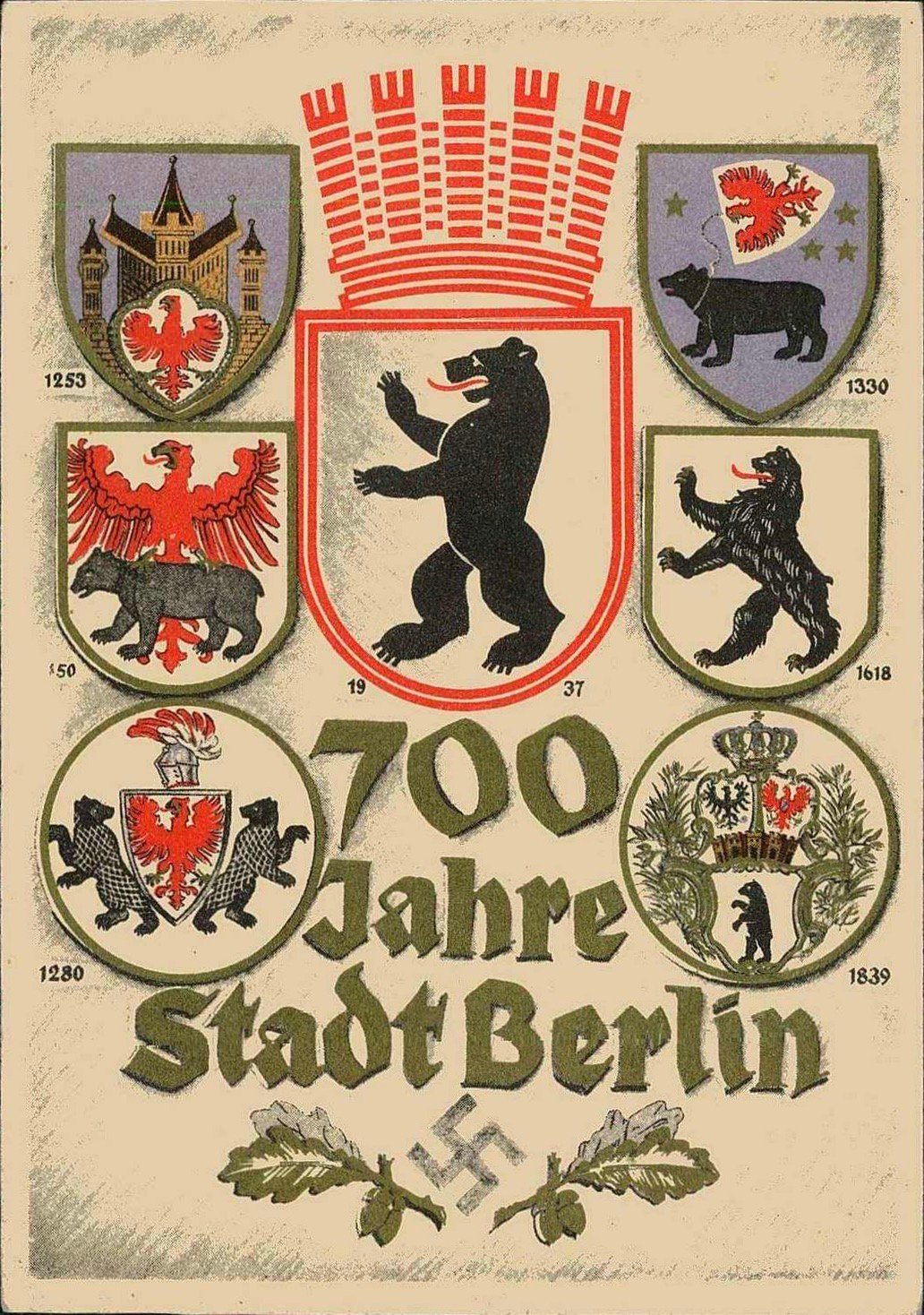

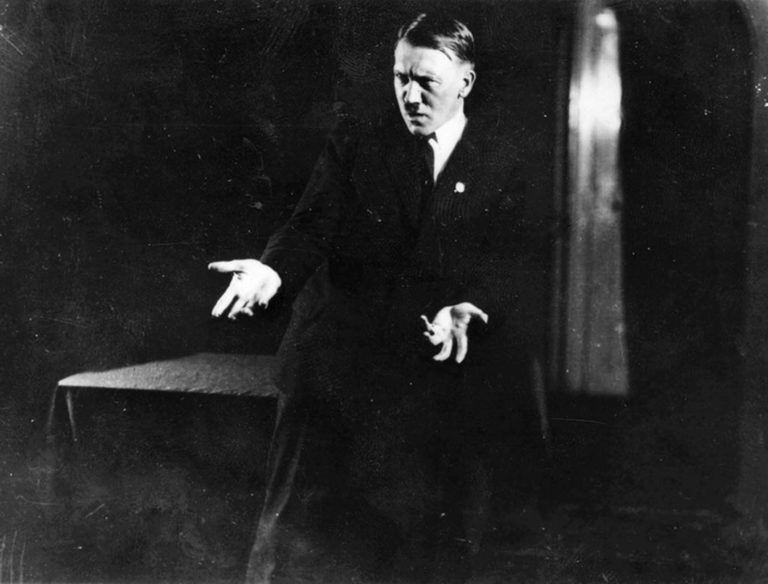

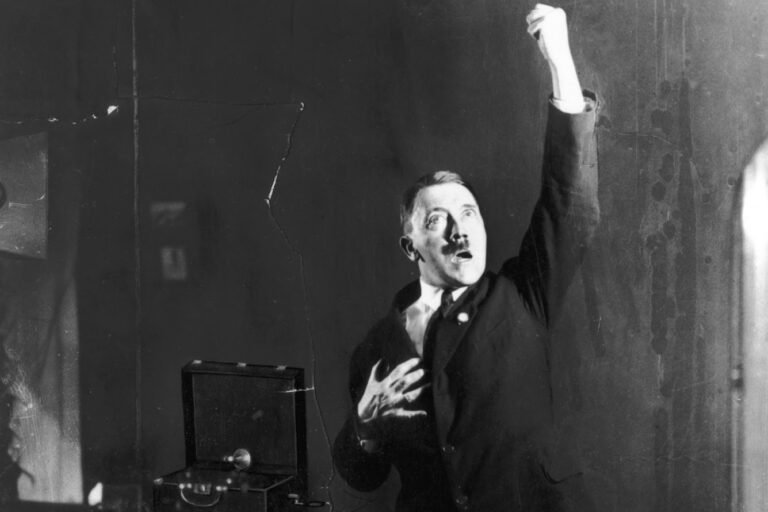

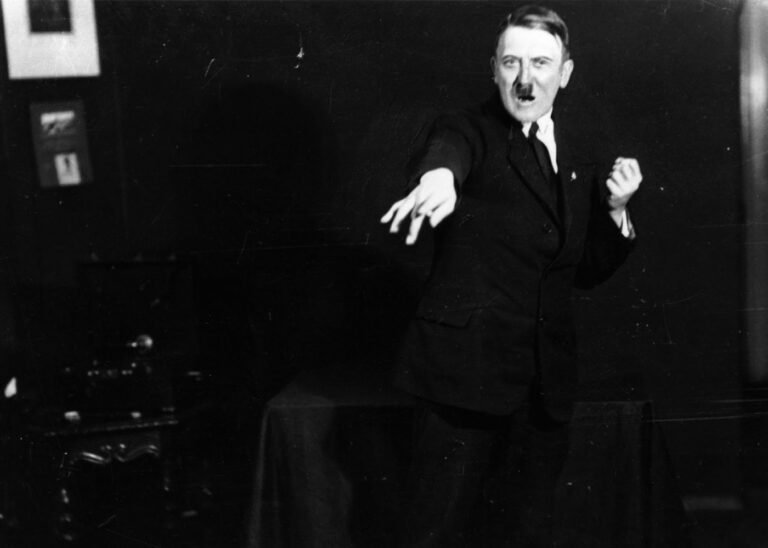

1937 - The Nazi Anniversary

“To Berlin, the Reich’s capital, I hope that it will remain the same as it is now in the future: hardworking, fanatical, generous and full of the joys of life. In a word: Nazi.”

Joseph Goebbels, Berlin’s Nazi Gauleiter & Propaganda Minister, 1937

In August 1937, more than four years after the Nazi Party’s violent seizure of power, the city of Berlin was gifted a grand birthday.

A prime opportunity to mold the city’s past into a shape that served the Party’s idea of an ideological future. Berlin’s 700 year anniversary was thus presented not just as a milestone but as a triumphant celebration, but of a re-imagined history. The choice of 1237 as Berlin’s foundational year was a calculated act of political maneuvering.

With no surviving founding charter for Berlin, the date was selected based on the first documentary evidence of its medieval sister city, Cölln, located across the Spree River.

The idea for such a celebration had been floated in the more liberal 1920s, a time of artistic fervor and intellectual debate, but was ultimately rejected by the authorities, who feared it would only amplify the city’s already palpable political instability.

The Nazis, however, had no such reservations. They understood the power of a good party.

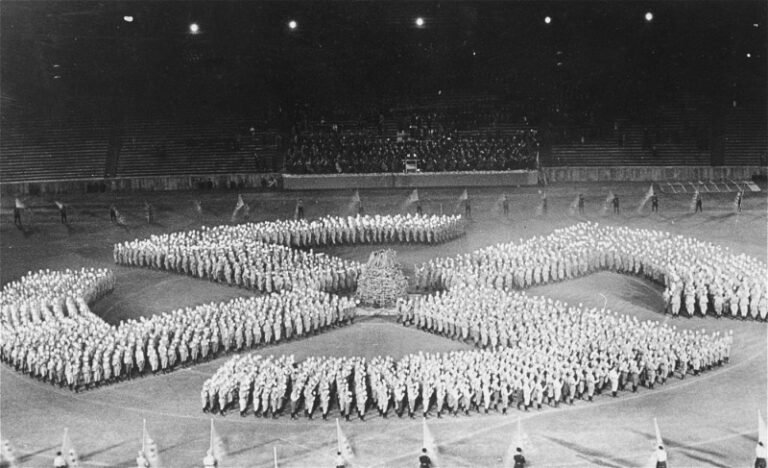

Public celebrations were a cornerstone of the Nazi propaganda machine, a way to whip up nationalistic fervor and create a sense of belonging to the “national community” as Berlin’s Nazi Mayor Julius Lippert himself phrased it. Though organised without direct funding from the national government, the celebration received the enthusiastic blessing of Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels.

Folkloric fairs with people in traditional attire filled the streets, harking back to a romanticised, purely Germanic past. An obligatory and grand parade marched down the stately Unter den Linden, in a carefully choreographed display of historical pageantry.

The 700th anniversary, while perhaps more modest than some of the regime’s other grand spectacles, was a meticulously staged affair.

The underlying message of the anniversary was hammered home in the event’s commemorative publication.

Mayor Julius Lippert’s assertion that “National Socialism is opposed to a stagnant and purely educational representation of the past” was a direct challenge to historical accuracy.

The publication declared to its readers: “You should no longer believe that Berlin emerged from Wendish [West Slavic] fishing villages. Berlin was consciously founded as a German city from the outset.”

This was a deliberate and calculated falsehood, an attempt to erase the city’s Slavic roots and supplant them with a narrative of pure, unadulterated German destiny. The Nazis championed the Middle Ages as Berlin’s golden era, using the 13th-century founding as proof of its preordained role as the center of the German Reich.

–

Welthauptstadt Germania

“Berlin will be, as a world capital, comparable only to ancient Egypt, Babylon, or Rome.”

Adolf Hitler

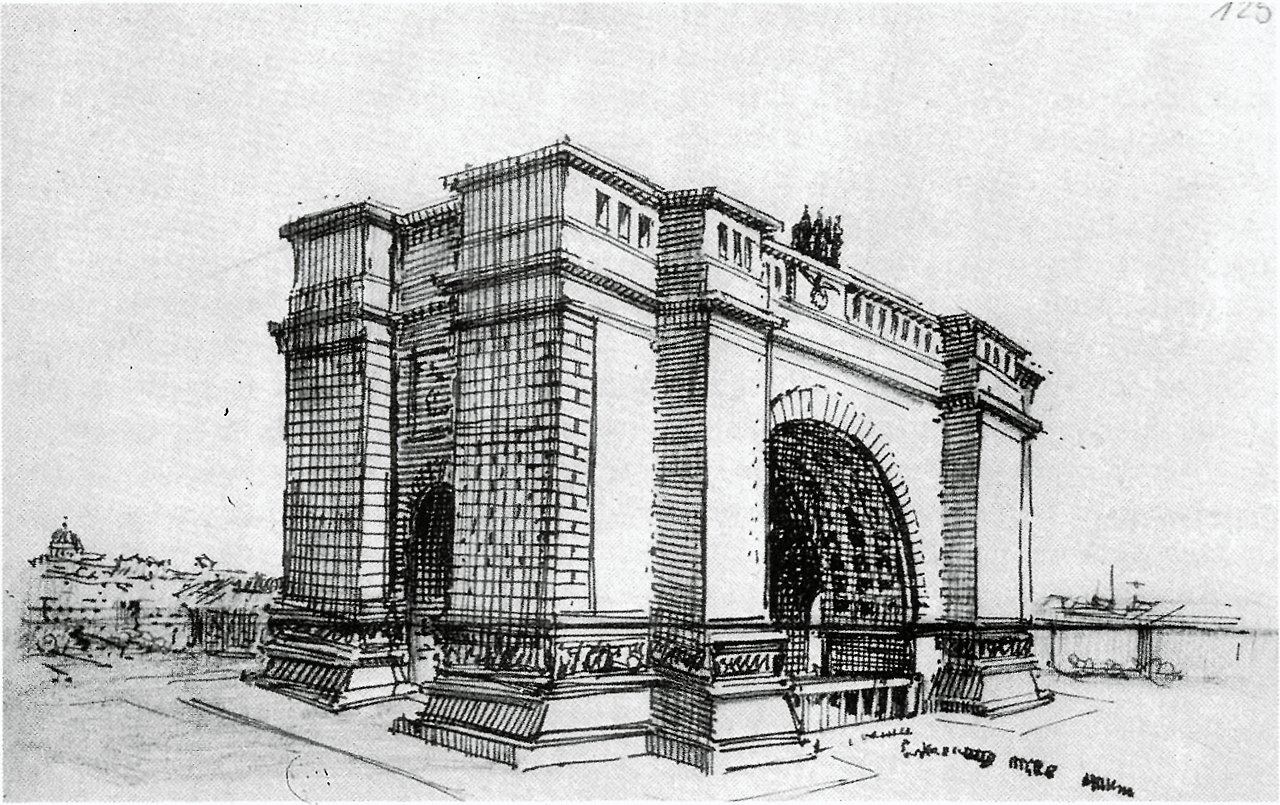

The 1937 anniversary was more than just a party; it was a cornerstone in the foundation of a new Berlin, a city to be reborn as ‘Germania’ – the capital of a world-dominating empire.

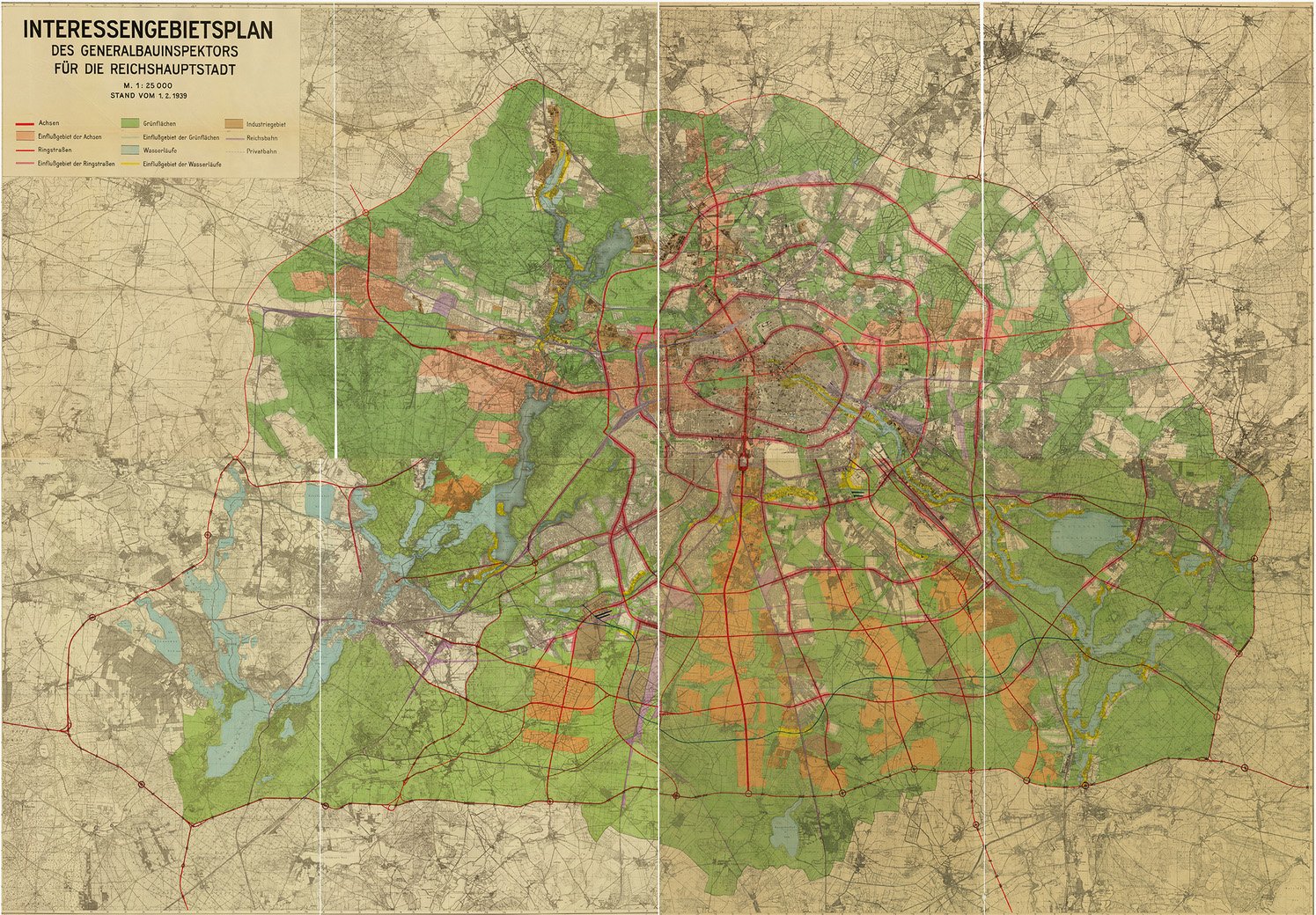

On January 30th 1937, the anniversary of Adolf Hitler’s appointment as Chancellor – and the start of the Nazi takeover – Hitler had appointed his favoured architect, Albert Speer, as the General Building Inspector for the Reich Capital. His mandate was nothing short of the complete architectural and demographic reshaping of Berlin. Speer’s position made him independent of the city’s government & mayor – answerable only to Adolf Hitler himself – and able to overrule Berlin and Brandenburg’s urban and regional regulations.

The same year, Speer’s design for the German pavilion was unveiled at the Paris World Fair (May-November 1937), presenting the world with a taste of what that Nazi future would look like – in form and function.

Fittingly, with the exhibitions of other nations plagued with delays, the only two pavilions completed for the opening day of the World Fair that year were the German and Soviet – both fatefully placed facing each other in a distinct clash of ideologies. Speer would later reveal in his autobiographies he designed the German pavilion to represent a bulwark against Communism, having secretly gained access to the Soviet plans before the event. Both structures competed in height and decoration – a Nazi eagle and swastika facing a Soviet couple raising a hammer and sickle to the sky.

In Berlin, Speer’s plans for Germania would channel this confrontational Weltanschauung into a project that was simply megalomaniacal in scale; a city of monumental boulevards and colossal structures.

A grand seven-kilometre (4.3-mile) north-south avenue, the ‘Prachtstrasse’, was to be the city’s new heart, culminating in the ‘Volkshalle’, a domed assembly hall so vast that the exhalations of its 180,000 occupants might have created a weather system inside the structure. Inspired by the Pantheon, the dome would have been 16 times higher than that of St Peter’s in Rome.

This grand plan for Berlin would have created a city visually intimidating and also hostile to pedestrians, with a chaotic road system, as Albert Speer reportedly did not believe in traffic lights or trams.

Berliners would have no chance to pause and take in the monstrosity.

Three exceptional traces of this intended world capital remain in Berlin – the Reich Aviation Ministry, the Olympic Stadium, and Tempelhof Airport – albeit all completed before 1937.

Hitler and Speer’s vision of Germania was intrinsically linked to the narrative promoted by the 700th anniversary – a city of monumental destiny, purged of its ‘undesirable’ elements and rebuilt as a testament to Nazi power. The project would be sanctioned by various edicts and decrees – leading to the purchase and destruction of property and any individuals who would stand in the way.

Were it not for the start of the Second World War in 1939, diverting resources and attention elsewhere, the Welthauptstadt could have materialised by 1950 according to Nazi plans.

In light of its timing, the historical revisionism of the 1937 anniversary celebrations in Berlin was not just about the past; it was about justifying the radical and brutal transformations planned for Berlin’s future. Establishing the ideological groundwork on which to build atop a marble and granite supercity. The city’s history was being weaponised to serve an agenda of architectural grandeur and racial purity.

Behind the Nazi pomp and planning of 1937 there was, however, an exaggeration – at best a confusion, at worst a lie – that Berlin was nobly conjured out of nothingness 700 years earlier by German settlers.

If the less convenient prescribed founding date of the settlement of Berlin had been celebrated by the Nazis – as a 700 year anniversary in 1944 – the mood would have been distinctly different to the optimism experienced in 1937.

–

1237 & 1244 - The Berlin-Cölln Dilemma

“Johann and Otto, Margraves of Brandenburg, have publicly declared and acknowledged, both orally and through their charters, before the clergy and the people, that the right and possession of the tithes from their estates located in the Brandenburg diocese, both in the new and the old lands, belong to the right and property of Brandenburg. … Done at Brandenburg, in the great hospital, on the feast day of the holy apostles Simon and Jude, the 28th of October in the year of the Incarnation of the Lord 1237, in the presence of the following faithful and upright men: Johannes, Dean of Halberstadt; Ulrich, Canon of St. Paul in Halberstadt; Johann, Pastor of Gardelegen; Reinhard, Canon of St. Sebastian in Magdeburg; Master Guntram; Heinrich von Nauen, Canon of Stendal; Symeon, Pastor of Cölln; Heinrich, Pastor of Plaue; and the knights…”

The first mention of Cölln in 1237

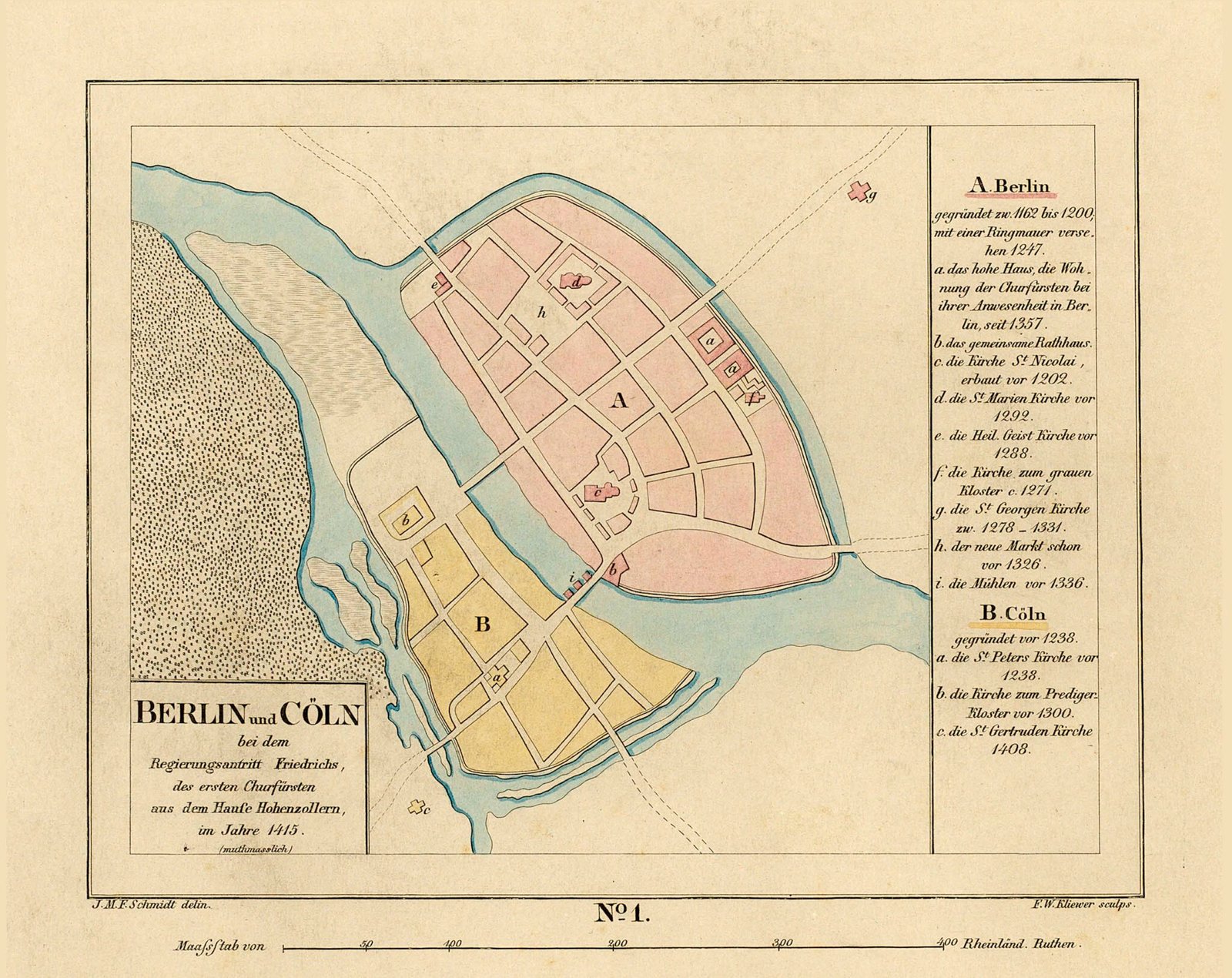

To truly understand Berlin’s origins, one must first come to terms with its dualistic beginnings and its ever-shifting boundaries.

The city as we know it today, a sprawling metropolis of over three and a half million people, is a relatively recent creation. Summoned into existence in 1920 – two years after the end of the First World War – as Berlin was expanded to encompass the surrounding farms, villages, and settlements. This current outer edge of the ring of Berlin is often colloquially referred to as the Speckgürtel (the fat belt) by the city’s residents.

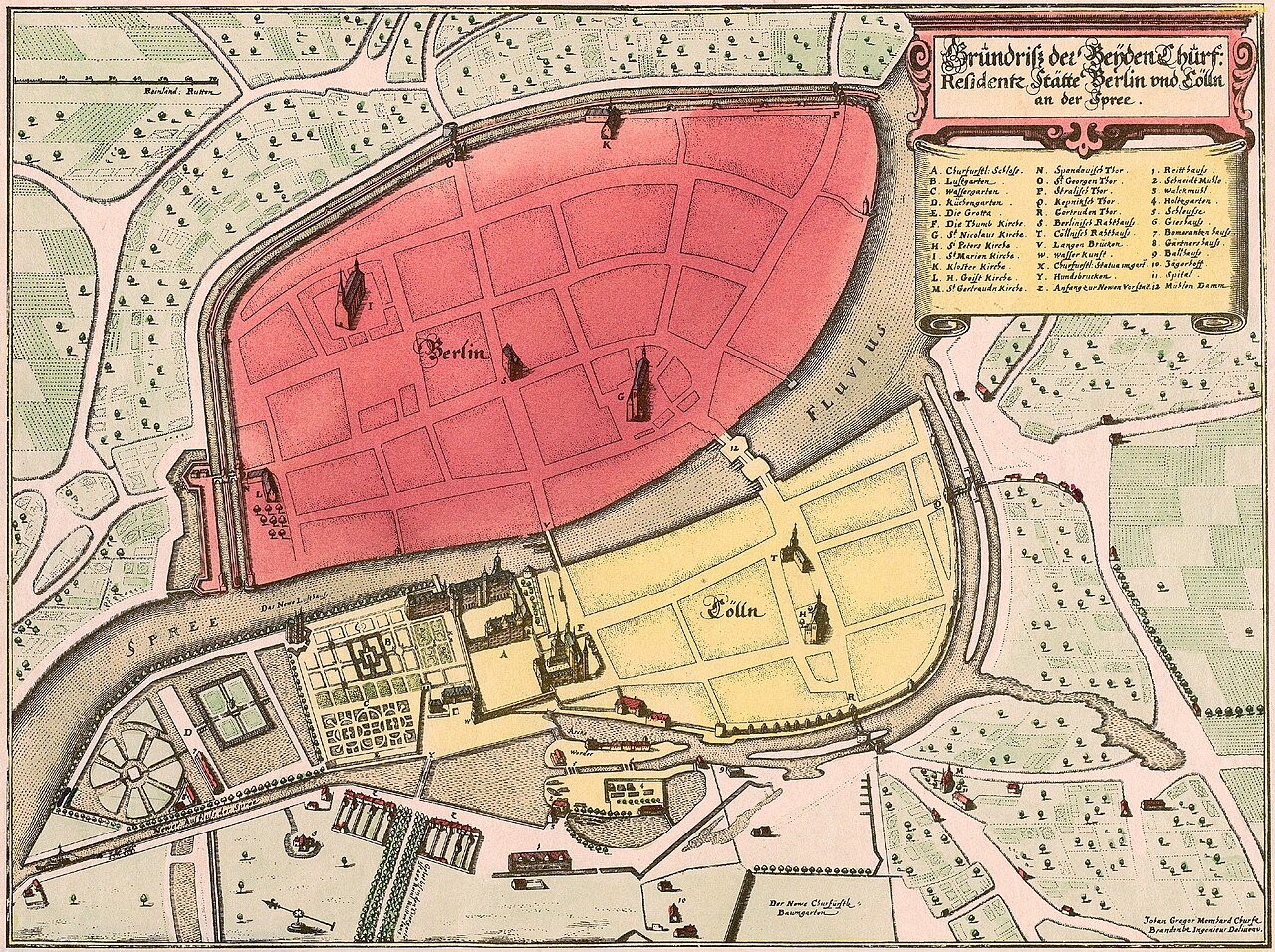

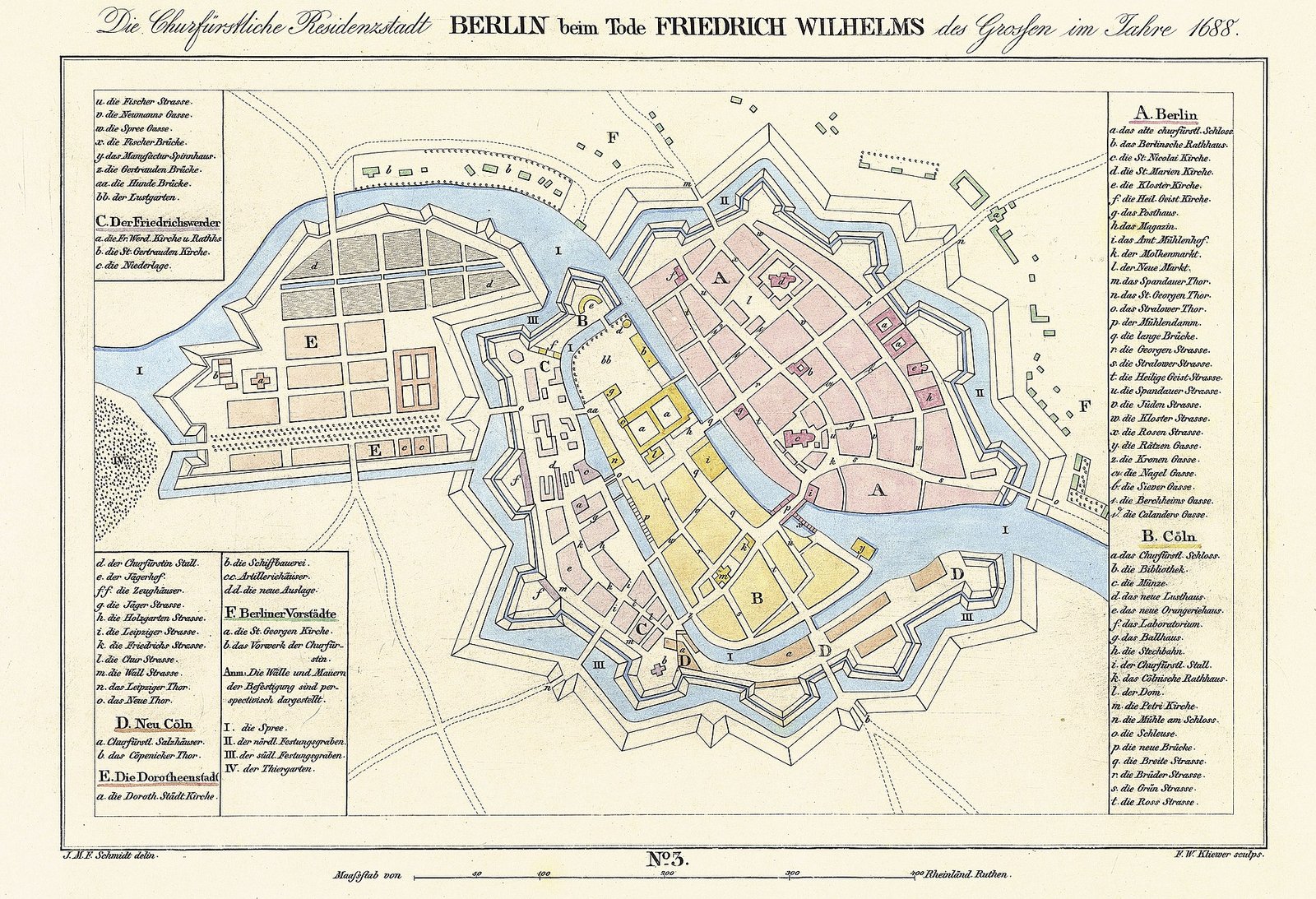

For centuries, however, so-called old Berlin was a far more modest affair, a friendly rivalry between two distinct realms. Twin towns nestled on the swampy banks of the River Spree.

Berlin occupied the north bank of the Spree, while Cölln sat on an island in the river itself.

Confronting this ‘Berlin-Cölln Dilemma’ is fundamental to understanding the city’s early development. It was a symbiotic relationship, with the two towns sharing resources and a common destiny, yet maintaining their own distinct identities.

Cölln can be dated to 1237 (the year often cited as that of Berlin’s founding) in a document issued on October 28th that year which mentions the pastor Symeon who witnessed a legal dispute between the Mark and a bishop of Brandenburg. It consists of sixty-two lines of ornately written manuscript with wax seals attached, detailing in Latin the rights and responsibilities of the electors of the region.

A document from 1247 refers to “Cölln near Berlin”; a mayor of Berlin named Marsilius is mentioned for the first time.

Berlin then first appears as a city (civitas) in 1251 and Cölln in 1261.

Only in 1307 did the two towns sign an agreement guaranteeing legal and military cooperation – with a new town hall built for a joint council on the Lange Brücke – establishing what could now be considered the relatively small, although significant, medieval core of future Berlin.

Eventually in 1709 Berlin and Cölln were officially unified – along with Dorotheenstadt, Friedrichsstadt, and Friedrichswerder – into a uniform community.

As Berlin and Cölln grew from this point into the central areas of the capital of Prussia and later Germany, the city morphed into different shapes. The ambitious plans of rulers and architects left their mark on the urban landscape.

One of the most significant of these had been the Memhard Plan of 1652. Johann Gregor Memhard, the court architect of the Great Elector, Friedrich Wilhelm, envisioned a fortified city, a star-shaped fortress in the Dutch style. While the full extent of Memhard’s vision was never realized, his plans guided the city’s expansion for a considerable time and reinforced the notion of a clearly defined urban space.

The real transformation, the moment Berlin exploded beyond its historical confines, came in 1920 with the passage of the Greater Berlin Act (Groß-Berlin-Gesetz). This groundbreaking legislation was a radical reimagining of the city.

Overnight, the old city of Berlin was merged with seven surrounding cities, 59 rural communities, and 27 Gutsbezirke (estate districts). The population skyrocketed, and the city’s geographical area expanded thirteen-fold, making it the third-largest city in the world by population, after London and New York.

This was the birth of the Berlin we know today, a city of distinct neighborhoods, each with its own character and history, all brought under a single municipal umbrella.

The 1920 expansion swallowed up once-independent towns like Spandau and Köpenick, which in fact, had their own rich and often longer histories than Berlin-Cölln itself. This act of administrative amalgamation, while necessary for the city’s modernization and growth, further complicated the question of its true age.

Is Berlin’s story that of the small medieval trading post on the Spree, or is it the story of the sprawling metropolis forged in the tumult of the 20th century?

Much like to question Germany’s provenance – and whether it is possible to refer to a German nation in any sense beyond the identity, shared language and traditions of a people before the unification of 1871.

Here, the Berlin-Cölln dilemma lies at the heart of this conundrum in the current German capital.

Despite being younger, the name “Berlin” ultimately triumphed, absorbing its sister city and a multitude of other settlements into its own identity.

But the ghost of Cölln remains, a reminder that the city’s origins are more complex, more nuanced than a single name and a single date might suggest. It is a reminder that Berlin has never been a static entity, but rather a constantly evolving organism, its boundaries expanding and contracting, its identity forever being renegotiated.

–

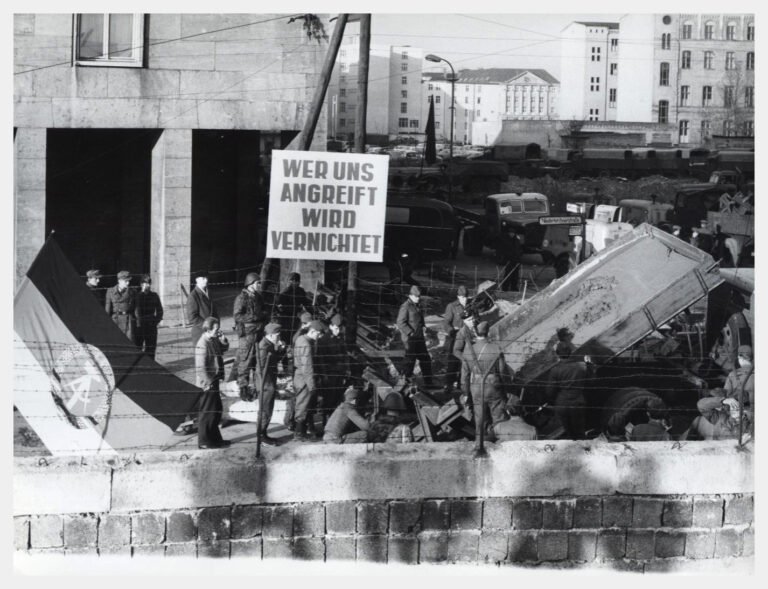

1987 - The Cold War Celebrations

“What could have possessed people to found a city in the middle of all this sand?”

Stendhal, 19th century French Realist

Half a century after the Nazi regime co-opted Berlin’s history for its own nefarious purposes, the city once again prepared to celebrate its birthday.

The year was 1987, and Berlin was a city split asunder.

The Berlin Wall had divided the city for over a quarter of a century. Yet, in a rare moment of symmetrical sentiment, both East and West Berlin decided to commemorate the city’s 750th anniversary. It was an occasion for both sides to lay claim to the legacy of the city’s distant past, to project their own vision of Berlin’s identity onto the grand canvas of history.

In West Berlin, the celebrations were a vibrant, often chaotic, and deeply introspective affair. The city, an island of democracy deep within the Soviet bloc, was determined to showcase its cultural dynamism and its commitment to confronting Germany’s dark past.

A pivotal moment in the West’s commemorative year came on June 12th 1987. Standing before the Brandenburg Gate, with the Berlin Wall as his backdrop, U.S. President Ronald Reagan delivered a speech that would echo through the annals of Cold War history. His challenge, delivered with theatrical flourish, was directed at the leader of the Soviet Union: “Mr. Gorbachev, open this Gate!… Tear down this Wall!”

While Reagan’s words were undoubtedly a powerful piece of political theater, they also encapsulated the West’s narrative of Berlin as a city of freedom, a beacon of hope in a divided world.

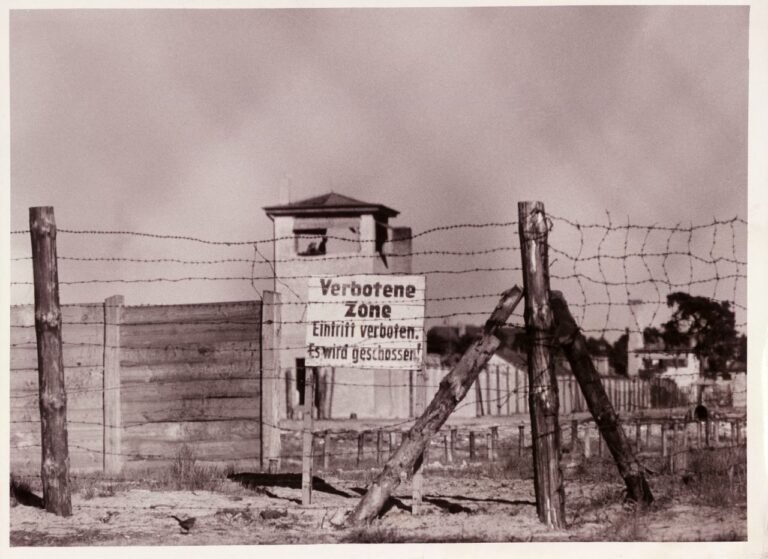

The 1987 celebrations in the West also saw the opening of a profoundly important institution: the Topography of Terror. Located on the site of the former headquarters of the Gestapo and the SS, this open-air exhibition meticulously documented the apparatus of Nazi terror. Its creation was a deliberate act of historical reckoning, a refusal to allow the horrors of the past to be forgotten.

This was a direct counterpoint to the Nazi’s cynical manipulation of history in 1937. Where the Nazis had sought to erase inconvenient truths, West Berlin was now unearthing them, forcing a confrontation with the city’s darkest chapter.

Across the wall, in East Berlin, the 750th anniversary was a far more orchestrated and state-managed affair. The German Democratic Republic (GDR) sought to portray itself as the true heir to Berlin’s progressive traditions, a socialist utopia that had risen from the ashes of fascism.

The celebrations in the East were a carefully curated spectacle of socialist achievement, with grand parades showcasing the nation’s industrial and technological prowess. These processions, however, sometimes verged on the surreal, featuring oddities like desktop computers on wheels and platoons of women in bikinis, a strange fusion of socialist realism and consumerist aspiration.

The East German government also invested heavily in the restoration of historical buildings in its sector, including the Nikolaiviertel, the city’s medieval heart. This was a clear attempt to claim ownership of Berlin’s pre-war heritage, to present the GDR as the careful custodian of the city’s soul.

Despite the deep political chasm that separated them, both East and West Berlin clung to the same foundational date: 1237.

The year chosen by the Nazis in 1937 had, ironically, become an accepted historical fact. The 1987 celebrations, in their own way, were also just as political as their 1937 predecessor.

They were a battleground of ideologies, with both East and West vying for control of the historical narrative. The city’s 750th birthday was a mirror reflecting the deep divisions of the Cold War, a moment when the past was once again pressed into the service of the present.

Yet, amidst the political posturing and the competing narratives, a deeper truth was beginning to emerge. Berlin, the divided city, was slowly, painfully, beginning to confront the totality of its complex and often contradictory history.

Two years after the 750th anniversary, the Berlin Wall would fall, and the city would embark on the arduous process of reunification. The debates over its history, its identity, and its very age, however, would continue.

For in a city as layered and as scarred as Berlin, the simple question of “how old?” will always be fraught with complexity, a testament to the enduring power of the past to shape the present.

–

Before 1237 - The Swamp and the Cross

“The story of Berlin begins at a spot now surrounded by a three-lane highway, a four-star hotel, and an Amazon engineering hub.”

John Kampfner, author of In Search of Berlin

To contemplate what Berlin was before 1237 is to pose a deceptively simple question.

The official date, as we’ve seen, is a matter of clerical paperwork, the first time the town of Cölln rated a mention in a medieval document. But the land itself, the marshy, sandy floodplain of the Spree River, paid no mind to officialdom.

It had a history that stretched back centuries before any German merchant-prince put quill to parchment. So what, exactly, was happening on this unpromising patch of Northern European bog in the years leading up to its celebrated birth?

First, let us dispense with a ghost. There were no Romans. For all their architectural and administrative might, the legions of the Roman Empire never made it this far east. Their frontier, the Limes Germanicus, lay hundreds of kilometres to the southwest. The land that would become Berlin was deep in what the Romans called Germania Magna—a vast, often-impenetrable forest inhabited by tribes they considered uncivilised. While Roman coins and goods may have trickled this far north through trade networks, no Roman soldier ever stood on a bridge over the Spree and planned a new colony. Berlin has no Roman foundations to claim.

Its foundations are, in fact, Slavic. For centuries, this was the western edge of the vast Slavic settlement area.

By the 8th century, two main tribes occupied the region: the Hevelli, centered around their fortress at Brandenburg an der Havel, and, more locally, the Sprevane, the ‘people of the Spree river’. These were not city-builders in the German sense. They lived in small, often-unfortified villages and wooden forts (gords), raising livestock, fishing the plentiful rivers, and clearing patches of the thick forest for crops. They were pagan, their spiritual world tied to the landmarks and nature that dotted the landscape.

Their presence lingers in the very DNA of Berlin’s place names: Köpenick, Pankow, Steglitz, Kladow—all have Slavic roots. The name Berlin comes from the word for marshland, Berl, from Old Polabian, an extinct West Slav language.

Cölln, however, is derived from the Latin word for settlement, colonia.

The decisive, violent shift came in the 12th century, a period of aggressive German expansion eastward known as the Ostsiedlung. The key figure in this drama was Albrecht the Bear, a ruthless and politically savvy Saxon nobleman. In 1157, after decades of brutal conflict, he definitively conquered the Hevelli fortress of Brandenburg, expelled its Slavic prince, and established himself as the first Margrave of Brandenburg. This act created the political and military entity in which Berlin would later be born. With Albert and his heirs came German knights, farmers, artisans, and, crucially, the Church. They brought with them new technology, new laws, and a new God.

But where in this story is Berlin?

For a long time, the answer was lost. In August 1380, a fire swept through the city, damaging the records of its first 150 years. The most important of these was the Stadtbuch (the city book), a detailed bureaucratic listing of every aspect of life in Berlin and Cölln.

What time and circumstance failed to destroy often fell prey to the bombs of the Second World War, as they obliterated the historic heart of Cölln around the Petrikirche (St. Peter’s Church), a site that had been one of two spiritual centres of the city for centuries. The other being the Nikolaikirche (St. Nicholas’ Church) in Berlin.

When archaeologists finally began a systematic excavation of the Petrikirche site, now known as Petriplatz, between 2007 and 2015, they uncovered a major part of Berlin’s origin story, buried in the mud.

What they found fundamentally rewrites the timeline. Digging through the layers, they discovered the foundations not of one, but of five successive St. Peter’s churches. The oldest was a simple wooden church, dated by dendrochronology—the science of tree-ring dating—to the 1170s or 1180s. Alongside it lay a graveyard with over 3,000 skeletons, the very earliest of which were buried oriented to the east, consistent with Christian practice, decades before the town’s “founding” in 1237.

These were the true first citizens of Cölln. Further excavations unearthed the foundations of a stone Latin school from around 1200 and more recently, in 2022, a medieval plank road dating back to the thirteenth century was discovered by archaeologists – having been preserved for over 800 years in a thick layer of peat.

The evidence from Petriplatz is irrefutable. Long before its first documentary mention, Cölln was already a functioning market town. It had a parish church, a cemetery, a school for the children of its elite, and a bustling population of merchants and craftsmen. The archaeological record shows a fusion of cultures; evidence of Slavic pottery and German goods coexisting, painting a picture not just of conquest, but of gradual settlement and assimilation.

So, what was Berlin before 1237?

It was the fledgling town of Cölln, a German-speaking colonial outpost with a Roman name on a Spree island, consciously founded in the latter half of the 12th century by German settlers pushing into Slavic lands. It was a frontier town, a place of wood and mud slowly giving way to stone, built around the organising principles of the market and the Cross.

The 1237 document wasn’t a birth certificate; it was the moment this already-living, breathing settlement finally made enough noise to be noticed by the wider world.

The true cradle of Berlin lies not in an archive, but in the excavated foundations of a long-forgotten church at Petriplatz.

–

Conclusion

“Like the metropolis in Faust, it has always been a rather shabby place – it is neither an ancient gem like Rome, nor an exquisite beauty like Prague, nor a geographical marvel like Rio. It was formed not by the gentle, cultured hand which made Dresden or Venice but was wrenched from the unpromising landscape by sheer hard work and determination. The city was built by its coarse inhabitants and its immigrants, and it became powerful not because of some Romantic destiny but because of its armies and its work ethic, its railroads and its belching smokestacks, its commerce and industry, and its often harsh Realpolitik.”

Alexandra Ritchie, author of Faust’s Metropolis

UNCLEAR – After navigating a labyrinth of political manipulation, archaeological revelations, and shifting city limits, the answer to as seemingly simple a question as to how old Berlin is remains stubbornly complex.

Contrary to past proclomations, there is no single, triumphant number to chisel into stone. Instead, the age of Berlin reveals itself to be less a question of fact and more a matter of definition.

If we seek the birth of the Berlin we know today—the sprawling, dynamic, and multifaceted megalopolis of distinct districts and boroughs—then the city is remarkably young.

This Berlin, the one that stretches from Wannsee to Köpenick, was born on October 1st, 1920, with the passing of the Greater Berlin Act. It was a bureaucratic creation, an act of administrative will that overnight forged a unified capital from a patchwork of cities, villages, and rural estates. In this sense, modern Berlin is barely a century old, a product of the turbulent optimism of the Weimar Republic.

Yet the city has twice celebrated a grand birthday using a date far more ancient. The irony, as we have seen, is that the hallowed year of 1237—the date weaponised by the Nazis in 1937 and commemorated on both sides of the Wall in 1987—has nothing to do with Berlin at all. It is the first documentary mention of its sister settlement, Cölln, located on an island in the Spree.

The land designated as “Berlin,” on the northern bank, only entered the written record seven years later, in 1244. The official birthday, therefore, is a historical shortcut, a convenient fiction that has proven politically useful but factually flawed.

But even these 13th-century dates, as the recent discoveries at Petriplatz prove, are merely the first time a German scribe took note of an already-existing reality. The story of this place did not begin with the arrival of Albert the Bear, even before his conquest this was the land of the Sprevane, a Slavic tribe whose presence can be traced back to at least the 8th century. Their wooden forts and fishing villages pre-dated the stone churches and market squares of the German settlers. They are the city’s deepest, most obscured foundation.

Although, the first settlers – a vast Germanic tribe known as the Semnones – can be traced back as far as 4000 BC.

Ultimately, the age of Berlin is a Russian doll of historical truths, each layer containing another.

There is the century-old metropolis of Greater Berlin; the roughly 780-year-old documented German town; and the far older, millennia-deep story of Slavic settlement.

The question is not how old Berlin is, but rather, which Berlin are you asking about?

As its true age lies not in a single year, but in the complex, often-conflicting, and deeply layered story of the land on which it stands.

***

If you’ve enjoyed reading this article, consider booking one of our private guided tours of Berlin.

Sources

Berlin Underworlds Association (Ed.) (2008), Mythos Germania: Shadows and Traces of the Reich Capital, Edition Berliner Unterwelten, ISBN 978-3-937863-09-0.

Bullock, Alan (1962), Hitler: A Study in Tyranny, Pelican Books, ISBN 978-0-14-013564-0.

Feist, Peter (2006), Als Berlin eine Festung war …, 1658–1746. In: Der historische Ort Nr. 27, 2. Auflage, Kai Homilius Verlag, Berlin, ISBN 3-931121-26-7.

Gontarczyk-Krampe, Beata (2020), Notmsparker’s Berlin Companion: Everything You Never Knew You Wanted to Know About Berlin, Beata Gontarczyk-Krampe.

Information Centre Berlin (1983), East Berlin, Verlag Information Centre Berlin, ISBN unavailable.

Kampfner, John (2023), In Search of Berlin: The Story of Europe’s Most Important City, Atlantic Books, ISBN 978-1-83895-992-0.

Kershaw, Ian (2000), Hitler: 1936–1945 Nemesis, W. W. Norton & Company, ISBN 978-0-393-32035-0.

MacLean, Rory (2014), Berlin: Imagine a City, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, ISBN 978-0-297-87042-0.

Mann, Hans (1959), Berlin: Eine kleine Heimatkunde, Dümmler Verlag, ISBN unavailable.

McKay, Sinclair (2022), Berlin: Life and Loss in the City That Shaped the Century, Penguin Books, ISBN 978-0-241-98715-5.

Melisch, Claudia Maria (Ed.) (2023), Petriplatz in Berlin-Mitte. Archäologisch-historische Studien, Michael Imhof Verlag.

Rabinbach, Anson; Gilman, Sander L. (2013), The Third Reich Sourcebook, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-26609-1.

Richie, Alexandra (1998), Faust’s Metropolis: A History of Berlin, Carroll & Graf, ISBN 978-0-7867-0529-2.

Shirer, William L. (1960), The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich: A History of Nazi Germany, Simon & Schuster, ISBN 978-1-4516-8191-2.

Speer, Albert (1970), Inside the Third Reich, Sphere Books, ISBN 978-0-7221-5309-2.

Spotts, Frederic (2002), Hitler and the Power of Aesthetics, Hutchinson, ISBN 978-0-09-179394-4.

White-Spunner, Barney (2019), Berlin: The Story of a City, Simon & Schuster, ISBN 978-1-4711-7635-0.

HISTORICAL ARTICLES

Mythbusting Berlin

Are There Any Nazi Statues Left In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

Visitors to Berlin often arrive expecting to find the physical remnants of the tyranny of the 20th century still standing – statues of dictators, triumphal arches, or bronze idols. Instead, they often find none. The stone symbols and statues of the Third Reich are still gazing down on them, however, hiding in plain sight. But why are there no statues of Hitler? Did the Allies destroy them all in 1945, or is the truth stranger

Could The Western Allies Have Captured Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

To contemplate a Western Allied capture of Berlin in 1945 is to challenge the established endgame of the Second World War. What was the true military and logistical feasibility of a Western Allied assault on the Nazi capital? What factors truly sealed Berlin’s fate, and what might have changed had the Allies pushed eastward?

Answering these questions means delving into the complex interplay of logistics, political maneuvering, and the competing visions for a post-war world

Did Any Of The Rothschild Dynasty Die In The Holocaust? – Mythbusting Berlin

The Rothschild name is synonymous with immense wealth, influence, and persistent conspiracy theories—especially during the era of Nazi Germany. Often targeted by antisemitic propaganda, the family’s survival during World War II has sparked myths about their supposed immunity from Nazi persecution. But did any Rothschild family member actually perish in the Holocaust? This article explores that compelling question, unraveling historical misconceptions and revealing the reality behind one of Europe’s most famous dynasties.

Did Frederick The Great Introduce The Potato To Germany? – Mythbusting Berlin

One of the more bizarre claims to fame attributed to the first King of Prussia is that the man who would go down in history known as Frederick the Great introduced the potato to Germany during his reign back in the 1700s. This starchy root vegetable has undoubtedly become a staple part of German cuisine – an essential addition to any plate of Schnitzel, Schweinshaxn, and Königsberger Klopse – however, whether Frederick the Great is

Did Hitler Escape To Argentina In 1945? – Mythbusting Berlin

Although Nazi leader, Adolf Hitler, certainly remains an inescapable figure, could there be any truth to the story of his escape to Argentina in 1945? That the most wanted man on earth could simply vanish, to spend the rest of his life peacefully in South American obscurity captivates imaginations. Yet, despite numerous investigations, this tale persists primarily as myth—fueled by speculation, hearsay, and conspiracy theories.

Did Hugo Boss Design The Nazi Uniforms? – Mythbusting Berlin

The idea that Hugo Boss – the man whose name now adorns expensive suits and fragrances – was the creative genius behind the Nazi uniforms suggests a terrifying collision of haute couture and holocaust – a marriage of high style and high crimes. The image is striking: a German tailor sketching the ultimate villain’s costume. But history, as usual, is far messier, more bureaucratic, and more banal than the internet memes suggest. To understand who

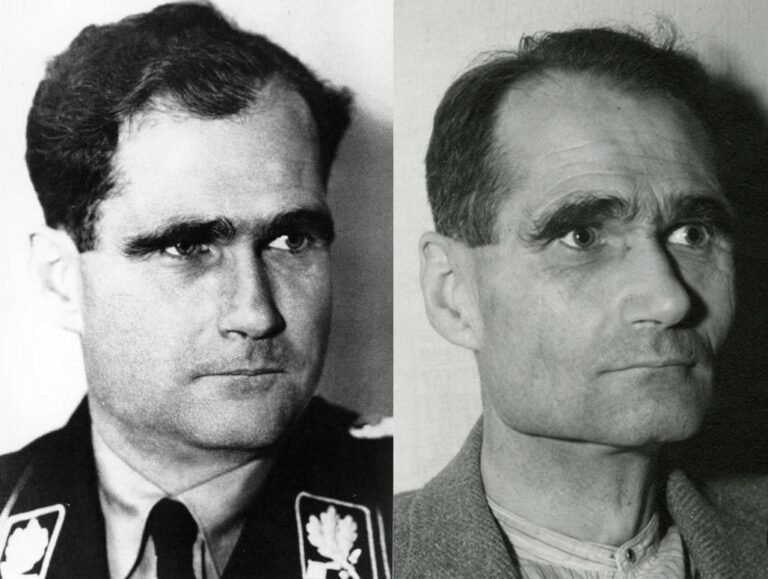

Did Rudolf Hess Really Commit Suicide? – Mythbusting Berlin

On a summer’s day in 1987, the last Nazi war criminal of the Nuremberg trials was found dead in a prison built for hundreds, yet for two decades, housed only him. The official verdict was suicide, a straightforward end to a life defined by fanaticism, delusion, and contradiction.

But the simplicity of the report belied the complexity of the man and the 46 years he had spent in Allied custody. In the meticulously controlled

Did The Nazis Develop Nuclear Weapons? – Mythbusting Berlin

The Nazi obsession with super-weapons became so serious in the closing stages of the Second World that Adolf Hitler personally believed that such ‘Wunderwaffen’ both existed in a usable form – and would save the country from defeat. Had the Nazis managed to develop nuclear weapons by 1945 – the outcome of the war would surely have been different. But how close were Hitler, Himmler, and his henchmen to developing an A-bomb?

Did The Nazis Invent Decaf Coffee? – Mythbusting Berlin

Persistent rumors claim that Nazis preferred their coffee anything but pure, leading some to wonder if they might have influenced the development of decaffeinated coffee. Although decaf was already widely available across Europe by the mid-20th century, speculation continues: could the Nazis really have played a role in popularizing—or even discovering—this caffeine-free alternative, or is this simply another caffeinated conspiracy cooked up to sensationalize an ordinary historical detail?

Did The Nazis Invent The Bicycle Reflector? – Mythbusting Berlin

The fruits of wartime ingenuity are plenty – so many, in-fact, that it has become somewhat of a worn cliche that as the guns start firing the innovators get to work, often solving problems while providing more problems for the enemy to overcome.The kind of progress that results in the production of newer improved, more lethal weapons, such as to increase the chances of victory.

Did The Nazis Run The Largest Counterfeiting Operation In History? – Mythbusting Berlin

During the Second World War the Nazis masterminded an astonishing plot to destabilise Britain by flooding its economy with counterfeit banknotes. Crafted in secret by concentration camp prisoners, this forged fortune became the most ambitious counterfeiting operation ever attempted. But was it history’s largest? Dive into the extraordinary tale of Operation Bernhard,

rife with deception, survival, and intrigue—revealing the truth behind one of the Third Reich’s most audacious schemes and its surprising legacy.

Did The Second World War End In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

When is a war ever truly over? When the last shot is fired in anger would seem like the best measure. Rarely, though, is it possible to gain insight into such a moment.

Remarkably, a record still exists of such a moment at the end of the First World War on the Western Front. A seismic register and recording of the last belching battery of British guns firing artillery across no-man’s-land, followed by a profound

Did The Spanish Flu Pandemic Help The Nazis Take Power? – Mythbusting Berlin

The devastating Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918-1919 struck amid Germany’s post-war turmoil, compounding social instability, economic hardship, and widespread political disillusionment. Could this catastrophic health crisis have indirectly paved the way for Nazi ascension? While often overshadowed by war and revolution, the pandemic’s profound psychological and societal impacts arguably contributed to the perfect storm, enabling extremist ideologies—including Nazism—to gain popularity and ultimately seize power in a fractured Germany.

Have Adolf Hitler’s Remains Been DNA Tested? – Mythbusting Berlin

In the smouldering ruins of Berlin in 1945, the world’s most wanted man vanished. Did Adolf Hitler, as official history attests, die by his own hand in the Führerbunker? Or did he escape, fuelling a thousand conspiracy theories that have echoed for decades? For years, the Soviets claimed to hold the gruesome proof of his death: a skull fragment and a set of teeth, locked away in Moscow archives. But in an age of definitive

How Did The Nazi Concentration Camps Differ From The Soviet GULAG?

The Nazi concentration camps and Soviet Gulag system have often been conflated in popular imagination—twin symbols of twentieth-century totalitarian horror. Yet the two systems operated on fundamentally different principles. One extracted labor to fuel industrialisation while accepting mass death as collateral damage; the other evolved into purpose-built machinery of genocide. Understanding these distinctions isn’t merely academic—it reveals how different ideologies produce different atrocities, and why Germany and Russia reckon with these legacies so differently today.

How Long Did It Take To Build The Berlin Wall? – Mythbusting Berlin

It is one of the most enduring images of the 20th century: a city divided overnight. The popular narrative tells us that Berliners went to sleep in a unified city and woke up in a prison. While the shock of August 13th 1961, was very real, the idea that the ‘Wall’ appeared instantly is a historical illusion. The physical scar that bisected Berlin was not a static creation, but a living, malevolent beast that evolved

How Many Assassination Attempts On Adolf Hitler Were There? – Mythbusting Berlin

Nazi leader, Adolf Hitler, projected an aura of invincibility, a man of destiny shielded by providence. But behind the carefully constructed image of the untouchable Führer lies a story of constant threat, of bombs that failed to detonate, and errant bullets that missed their mark. Unearth the hidden history of the numerous attempts on Hitler’s life as we explore the courage of those who tried to change the course of history and the devil’s luck

How Many Jews Died In The Holocaust? – Mythbusting Berlin

The answer to the question posed of how many Jews died in the Holocaust is a simple one: too many. That merely one death was an unforgivable obscenity is a fundamental and necessary realisation in understanding the capriciousness of this unparalleled racial genocide. To comprehend, however, the full number of Jews murdered in Europe by the Nazi regime in the 1930s and 1940s is a detective story of epic proportions: the evidence overwhelming, multifaceted, and

How Many People Died Trying To Escape East Germany? – Mythbusting Berlin

The image of the Berlin Wall is seared into our collective memory, a concrete symbol of Cold War oppression. We think of the daring escapes and the tragic deaths of those who failed. But that well-known number is only a fraction of the truth. The story of those who died trying to escape East Germany is far broader and more complex than most imagine, stretching along a thousand-kilometer border and out into the cold waters

How Old Is Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

A relatively new arrival in Europe, Berlin is over 1000 years younger than London, nevermind Rome or Athens, Jerusalem or Jericho. Just how old is Berlin though?

A question fraught with false assumptions and distortions – that has more often than not been answered with propaganda as it has with the cold hard truth.

Was Adolf Hitler A Drug Addict? – Mythbusting Berlin

Solving the enigma of the ‘Führer’ has become a preoccupation for many, since the arrival of the Austrian-German onto the world stage – although moving beyond the mythology without falling into the trap of prejudically extrapolating on the psychopathography of Hitler or demonising so as to excuse his actions has proven problematic. What to make of the man who became more than the sum of his masks? The painter; the military dilettante, the mass murderer,

Was Adolf Hitler A Freemason? – Mythbusting Berlin

History abhors a vacuum, but adores a mystery. Such is the speculative fiction suggesting a secret allegiance behind the rise of the Third Reich – that the catastrophe of the Second World War was orchestrated from the shadows of a Masonic lodge. The image of Adolf Hitler—the drifter from Vienna turned dictator—as a covert initiate of the very brotherhood he publicly reviled, however, creates a paradox that collapses under scrutiny. As when we unlock the

Was Adolf Hitler Gay? – Mythbusting Berlin

In the shadowy corridors of Third Reich history, few questions provoke as much tabloid curiosity and scholarly exasperation as the sexuality of Adolf Hitler. For decades, rumors have swirled—whispered by political enemies in 1930s Munich, psychoanalyzed by American spies in the 1940s, and sensationalized by revisionist authors today. Was the dictator who condemned thousands of men to concentration camps for “deviant” behavior hiding a secret of his own? By peeling back the layers of propaganda,

Was Adolf Hitler Jewish? – Mythbusting Berlin

Was the dictator who orchestrated the murder of millions of European Jews secretly one of them? It is perhaps the darkest irony imaginable, a story whispered for decades in backrooms, bars, and conspiracy forums alike. The most-common rumour – the ‘Frankenberger Myth’ – suggests that Adolf Hitler’s paternal grandfather was Jewish, a secret so damaging it could have unraveled the entire Nazi regime. But where does this claim come from? And, more importantly, is there

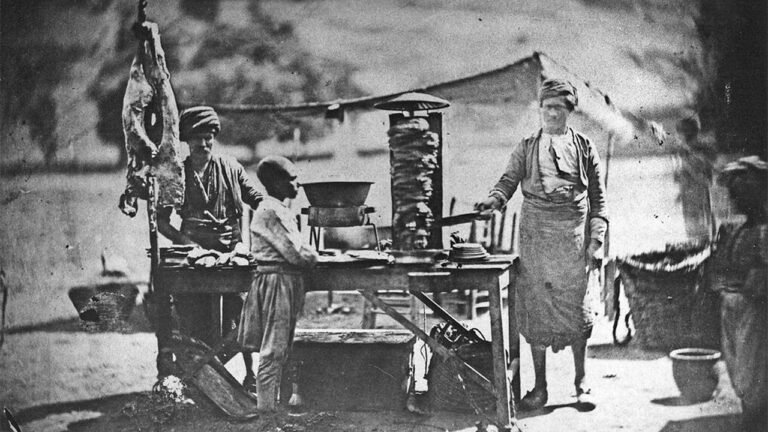

Was Currywurst Invented In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

Explore the story behind what many consider Berlin’s most iconic snack—the ever-so-humble Currywurst. Often hailed as an enduring symbol of culinary creativity amid Cold War scarcity, this humble dish has inspired fierce debate about its true origin. But was it genuinely invented here in Berlin, or have proud locals simply adopted and elevated this spicy street-food favorite into legendary status all their own?

Was Fanta Invented By The Nazis? – Mythbusting Berlin

As one of the most secretive organisations in the world, the Coca Cola corporation refuses to share its secret recipe with anyone. Famously insisting only on shipping the base syrup of its drinks to plants around the world to be carbonated and distributed.

This combined with the trade limitations of the Second World War may have led to the introduction of one of the most popular soft-drinks in the world. But could it be true:

Was Frederick The Great Gay? – Mythbusting Berlin

Frederick II of Prussia, better known as Frederick the Great, is often remembered as the archetypal enlightened monarch – a brilliant military commander, patron of the arts, and learned philosopher. Yet behind the stern portraits of this 18th-century warrior-king lies a personal life long shrouded in intrigue and speculation. Intrigue around the king’s sexual orientation has persisted through the centuries, chiefly revolving around one question: Was Frederick the Great gay?

Was Henry Ford A Nazi? – Mythbusting Berlin

US auto tycoon, Henry Ford, holds the ignominious distinction of being the only American Adolf Hitler praised by name in his National Socialist manifesto: ‘Mein Kampf’. This was not, as it turns out, the only connection between Ford and the Party of Hitler, Himmler, and the Holocaust.

Ford’s overt affinity with the Third Reich reveals a troubling past. How deep these connections ran, and how consequential they were for both sides, is a chapter

Was The Colour Blue Invented In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

Tracing the true history of blue—from ancient Egyptian dyes to the accidental discovery of Prussian Blue in a Berlin lab. We’ll debunk myths about seeing blue, explore colonial indigo plantations, scale mountains with a cyanometer, and trace Van Gogh’s starry skies—all to answer one question: how did Berlin shape our understanding of the world’s rarest color?

Was The Döner Kebab Invented In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

Unlikely icon of immigrant success; fast food symbol of the working class; over-hyped midnight disco eat; or culturally appropriated cuisine? Its influence goes far beyond layers of seasoned meat and fresh vegetables stuffed into pita bread. But does Berlin deserve credit as the Döner Kebab’s true birthplace, or has the city merely refined and popularized a culinary tradition imported from elsewhere?

Was The Fall Of The Berlin Wall An Accident? – Mythbusting Berlin

On a seasonally crisp night in November 1989, one of the most astonishing events of the 20th century occurred. After twenty eight years, three months, and twenty eight days of defining and dividing the German capital, the Berlin Wall ceased to exist – at least in an abstract sense. Although the removal of this symbol of the failure of the East German system would take some time, its purpose – as a border fortification erected

Was The Nazi Party Democratically Elected? – Mythbusting Berlin

The myth persists that Adolf Hitler rose to power through popular democratic choice. Yet history reveals a darker, more complicated truth. Hitler’s ascent involved exploiting democratic institutions, orchestrating violence, propaganda, and political intrigue—not a simple election victory. Understanding how Germany’s democracy collapsed into dictatorship helps illuminate the dangerous interplay between public desperation, elite miscalculations, and extremist ambition, providing crucial lessons for safeguarding democracy today.

Were The Allied Bombings Of Germany War Crimes? – Mythbusting Berlin

The history of the Allied bombing of Germany during the Second World War still triggers fierce debate. Was reducing cities to rubble a necessary evil – justice from above in a just war – or an unforgivable crime? Can the intentional targeting of civilians ever be justified as militarily necessary?

In a conflict where all rules seemed to vanish, an even more pertinent question persists: by the very standards they would use to judge their

Were The Nazi Medical Experiments Useful? – Mythbusting Berlin

Before the Nazi period, German medicine was considered the envy of the world – a shining monument to progress. But deep within that monument, a rot was spreading, one which would collapse the entire structure into an abattoir. From the wreckage, we are left with a profoundly uncomfortable inheritance: a moral enigma wrapped in doctor’s whites.

What to make of the data, the images, and the terrible knowledge gleaned from unimaginable human suffering. Whether

What Are The Origins Of The Nazi Salute? – Mythbusting Berlin

A specter is haunting the modern mind, a gesture so charged with the dark electricity of history that its mere depiction can unleash a storm of controversy.

It is a simple movement: the right arm, stiff and straight, raised to the sky. But in that simplicity lies a terrifying power, a symbol of a regime that plunged the world into an abyss and a chilling reminder of humanity’s capacity for organised hatred.

This

What Are The Origins Of The Nazi Swastika? – Mythbusting Berlin

Long before the legions of the Third Reich marched beneath its stark, unnerving geometry, the swastika lived a thousand different lives. It was a symbol of breathtaking antiquity, a globetrotting emblem of hope and good fortune that found a home in the most disparate of cultures. To even begin to understand its dark 20th-century incarnation, one must first journey back, not centuries, but millennia.

What Are The Pink Pipes In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

A first-time visitor to Berlin could be forgiven for thinking the city is in the midst of a bizarre art installation. Bright pink pipes, thick as an elephant’s leg, climb out of the ground, snake over pavements, arch across roads, and disappear back into the earth. Are they part of a complex gas network? A postmodern artistic statement? A whimsical navigation system? These theories, all logical, are all wrong. The truth is far more elemental,

What Do The Colours Of The German Flag Symbolise? – Mythbusting Berlin

What does a flag mean? Is it merely a coloured cloth, or does it hold the hopes, struggles, and identity of a nation? The German flag, with its bold stripes of black, red, and gold, is instantly recognisable. But the story of its colours is a tumultuous journey through revolution, suppression, and reinvention. The common explanation for their symbolism is a simple, romantic verse, yet the truth is a far more complex and contested tale,

What Happened To Adolf Hitler’s Alligator? – Mythbusting Berlin

It is often said that you can tell a lot about a person by their relationship with animals; that owners often come to look and behave like their pets. Or is it perhaps more that people choose their pets to correspond to their personality? Nazi leader Adolf Hitler’s love of dogs, for example, is well documented but what is there to make of his relationship with reptiles?

What Happenened To The German Royal Family? – Mythbusting Berlin

When the smoke cleared over the trenches in November 1918, the German Empire had evaporated, and with it, the divine right of the Hohenzollern dynasty. Conventional wisdom suggests the family simply vanished into the sepia-toned obscurity of history books—exiled, forgotten, and irrelevant. But dynasties, like weeds in a landscaped garden, are notoriously difficult to uproot entirely. The story of the German royals did not end with the Kaiser’s flight to Holland; it merely shifted gears.

What Is The Difference Between Fascism & Nazism? – Mythbusting Berlin

While the terms ‘Fascist’ and ‘Nazi’ are often bandied around interchangeably as shorthand for tyranny – Italian fascism and German National Socialism were distinctly different beasts. Albeit ideological kin. One an ideology of state-worship, born from post-war chaos and national pride; the other built upon a fanatical, pseudo-scientific obsession with race. Two peas in the same totalitarian pod – twins in tyranny – more succinctly summarised as the Nazi chicken to the Fascist egg.

What Was Checkpoint Charlie? – Mythbusting Berlin

Checkpoint Charlie remains among Berlin’s most visited historical sites, famed worldwide for its significance during the Cold War. Originally established as a modest border-crossing point, it evolved dramatically over the decades into an international symbol of freedom, espionage, and intrigue. Today, critics and locals often dismiss it as little more than a tourist trap—Berlin’s Disneyland—but how exactly did Checkpoint Charlie get its peculiar name, and what truths hide behind its popularity?

What Was Prussia? – Mythbusting Berlin

Prussia’s legacy is both remarkable and contentious—once a minor duchy, it rose dramatically to shape modern European history. Renowned for military discipline, administrative efficiency, and cultural sophistication, Prussia was instrumental in uniting the German states, laying foundations for a unified Germany. But how did this kingdom, with its roots in Baltic territories, achieve such prominence, and why does its complex history continue to evoke admiration, debate, and occasional discomfort in Germany today?

What Was The Berlin Airlift? – Mythbusting Berlin

In the ruins of 1948, the silence of Berlin was not a sign of peace, but a held breath before a new catastrophe. The city, drowning in rubble and political intrigue, became the staging ground for the twentieth century’s most audacious gamble. While popular history remembers the chocolate parachutes and smiling pilots, the reality of the Berlin Airlift was a terrifying operational nightmare born from a ruthless currency war. It wasn’t just a humanitarian mission;

What Was The Socialist Kiss? – Mythbusting Berlin

It is one of the most curious and enduring images of the Cold War: two middle-aged, grey-suited men, locked in a fervent embrace, their lips pressed together in a kiss of apparent revolutionary passion. This was the ‘Socialist Fraternal Kiss’, a ritual that, for a time, seemed to encapsulate the unwavering solidarity of the Eastern Bloc.

But what was behind this seemingly intimate gesture? Was it a genuine expression of camaraderie, a piece of

Who Built The Berlin Wall? – Mythbusting Berlin

One of the most common questions I have encountered from people curious about Berlin, and often so cryptically phrased. Who built the Berlin Wall? A simple five-word query, yet one that can be read one of two ways. More than thirty years since the ‘Fall of the Wall’, the story of its construction continues to baffle many who are mainly familiar with its existence through knowledge of its importance…

Who Really Raised The Soviet Flag On The Reichstag? – Mythbusting Berlin

One iconic photograph has come to symbolise the Red Army’s victory over Nazi Germany in 1945—the Soviet flag waving triumphantly above Berlin’s battered Reichstag building. Yet behind this enduring image lies controversy, confusion, and political manipulation. Who truly raised the Soviet banner atop the Reichstag? Was it a spontaneous act of heroism or carefully staged Soviet propaganda? Decades later, unraveling the truth reveals surprising layers beneath the mythologized symbol of Soviet triumph.

Who Was Really Responsible For The Reichstag Fire? – Mythbusting Berlin

Various theories have been posited as to who actually set fire to the German parliament in 1933. Was it the opening act in an attempted Communist coup or a calculated false flag operation carried out by elements of the Nazi Party, intended to create the conditions necessary for introducing single-party rule? And what part did the young man from Holland, arrested shirtless inside the building the night of the fire, play in this event?

Who Were The Last Nazis On Trial? – Mythbusting Berlin

More than eighty years after the Holocaust, courtrooms across Germany still echo with testimony from the final chapter of Nazi justice. Centenarian defendants in wheelchairs, their faces hidden behind folders, arrive to answer for crimes committed in their youth. These are not the architects of genocide—those men faced their reckoning at Nuremberg decades ago. These are the guards, the secretaries, the bookkeepers: ordinary people who enabled extraordinary evil. Their trials represent a legal revolution: the

Why Is Berlin The Capital Of Germany? – Mythbusting Berlin

There was little in its humble origins—as a twin trading outpost on a minor European river—to suggest that Berlin was destined for greatness. It sits on the flat expanse of the North European Plain, a landscape once dismissively referred to as the “sandbox of the Holy Roman Empire.” Unlike other world capitals, it lacks breathtaking scenery or a naturally defensible position. It is a city built not on majestic hills or a grand harbour, but