“Unless a document can be found in which Frederick relates what he did and with whom, a residual doubt must remain. The cumulative weight of evidence, however, is difficult to resist.”

Tim Blanning, author of Frederick the Great

Among the numerous rulers of Prussia, only one has truly transcended the weight of his official title, becoming known to the world not merely by formal designation, but by the essence of his character captured in an acclamatory nickname.

Frederick the Great.

While it must be admitted that his fellow Prussian kings would sport descriptive, if less grand, monikers – the militaristic ‘Soldier King’ Frederick William I, the dreamy ‘Romantic on the Throne’ Frederick William IV, or the belligerent ‘Grapeshot Prince’ William I – only Frederick earned the explicit epithet ‘Great’.

And deservedly so.

Reigning from 1740 to 1786, he was a figure of dazzling complexity and contradiction.

A military genius who faced down the combined might of Austria, France, and Russia during the crucible of the Seven Years’ War, securing Prussia’s place among the continental giants. An ‘Enlightened Despot’ who corresponded with Voltaire, championed religious tolerance (for some), reformed the legal system, and abolished torture. A sensitive artist, a gifted flautist who composed over 200 sonatas and concertos, filling his palaces with music. A Francophile writer whose preferred language for philosophy and poetry was French, often to the chagrin of German nationalists then and since.

He was, by any measure, a titan – shaping his kingdom, influencing European thought, and leaving an indelible mark on history. His reputation, like his achievements, is larger than life, debated and dissected for over two centuries.

Yet, beneath the layers of military brilliance, philosophical musings, and artistic expression, lies a persistent, often whispered, sometimes deliberately obscured question – formulated in many ways but distillable to one catechism: Was Frederick the Great gay?

Did this childless monarch leave the throne without heir due to his preference for the company of men?

Was that palatial Rococo refuge of Sanssouci – Frederick the Great’s villa in Potsdam – more than a sanctuary from the cares of state but perhaps also, from other, more personal constraints?

While the private identity of one of the most celebrated kings in European – and indeed world – history may have shaped his behaviour at the time, it in no way alters the achievements, and legacy, of the man who would become known as simply ‘Great’’.

In-fact, during his lifetime, Frederick would be referred by his supporters and enemies alike by an additional name – that perhaps sheds more light on this exploration than his oft-repeated moniker.

He was also known as ‘Frederick the Unique’.

–

The Crown Prince & The Price Of Self

“The most beautiful girl in the world would be a matter of indifference to me, but tall soldiers—they are my weakness”

Frederick Wilhelm I, father of Frederick the Great

Prussia.

The very name conjures images of ramrod discipline, goose-stepping soldiers, and stern, unyielding monarchs. It speaks of militarism, bureaucracy, and a certain austere efficiency that forged a kingdom from the sandy plains of Brandenburg into a major European power.

Among the architects of this transformation, Frederick the Great’s father – Frederick William I – stands out as the man who successfully militarised the lands controlled by the Hohenzollern royal family. Laying the foundations for the military conquests of his more celebrated son.

Not only did Frederick William I have a lasting effect on the destiny of Prussia, and with it what we now consider Germany – but he was also the domineering male figure in the life of his first son, and the tyrant who would torture Crown Prince Frederick throughout his painful adolescence.

King Frederick William I, the ‘Soldier King’, was Frederick’s polar opposite – a man of crude tastes, obsessive militarism, and visceral piety, who despised everything his son seemed to represent.

The ‘Soldier King’ was a paradox himself. While enforcing brutal discipline and austerity, he harboured his own peculiar obsessions. His regiment of ‘Potsdam Giants’, exceptionally tall soldiers recruited (sometimes forcibly) from across Europe, was his pride and joy. He doted on them, fussed over their uniforms, and reportedly declared, with unnerving candour, “The most beautiful girl in the world would be a matter of indifference to me, but tall soldiers—they are my weakness.” While likely not indicating sexual interest in the modern sense, this quote reveals a profound homosocial fixation, an intense preference for male company and military aesthetics, albeit channelled into a hyper-masculine, acceptable form.

For his sensitive, intelligent, artistically inclined son, however, the King reserved only scorn and suspicion.

From a young age, the Crown Prince sought out his passion in music – particularly the French flute – poetry, philosophy, and French culture – all considered dangerously effeminate by his father.

His admonishing father would berate and beat the Crown Prince, publicly denouncing him as a ‘sodomite’ and ‘effeminate’. Whether the King truly believed his son engaged in forbidden acts or simply used the most damning insults he could conjure to express his contempt for Frederick’s perceived lack of manliness is unclear. But he would have known the gravity of such accusations.

The King saw these pursuits as undermining the martial virtues necessary for a future Prussian ruler. He subjected Frederick not only to a brutal upbringing designed to stamp out these tendencies but forced the Crown Prince into a red tape existence of regimentation and service to the state.

Frederick’s days were spent on the parade ground, his hair scraped back into a mandatory military pigtail, encased in the stiff uniform he loathed.

Behind the King’s back, Frederick’s more sympathetic mother, Sophia Dorothea, arranged for the renowned flautist Johann Joachim Quantz to secretly visit Potsdam twice a year to give the prince lessons. His flute playing, his chief source of solace and genuine talent, had to be practiced in secret. These clandestine sessions, however, were fraught with risk and the possibility that Frederick might be discovered in flagrante delicto by his captious father.

One famous incident captures the oppressive atmosphere: Frederick William I burst in unexpectedly while his son was absorbed in music. Quantz barely managed to scramble into a wardrobe, along with Frederick’s close friend and confidante, Lieutenant Hans Hermann von Katte. The King, discovering a forbidden red silk dressing gown Frederick favoured for his performances, furiously threw it onto the fire.

No such comfort should be allowed to the Prince while his father demanded the tough conditioning of puritanical austerity.

Furthermore, a collection of French books, symbols of Frederick’s decadent tastes, was confiscated and ordered sold.

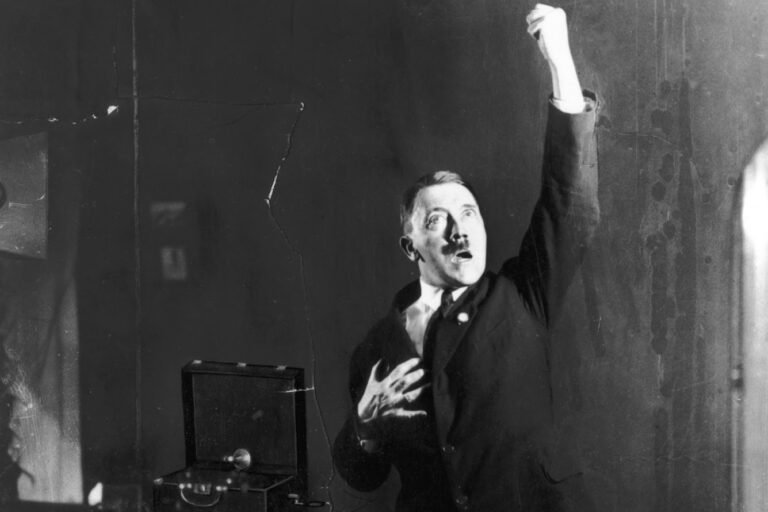

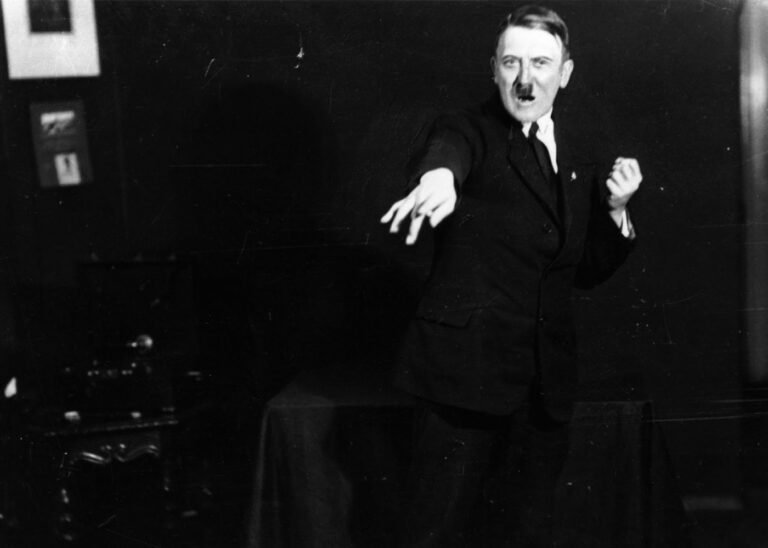

This and further episodes of degradation and humiliation of Frederick by his father would be later cast in National Socialist propaganda, such as the 1940 film Frederick, as being a necessary step in the training of the future king to hardship. Proof that his father knew the value of struggle and sacrifice over the temptations of comfort and pleasure. The reality for young Frederick was likely far more traumatic: a desperate struggle for survival and selfhood against a tyrannical father who seemed determined to crush his spirit.

Driven to despair, in 1730, the 18-year-old Frederick made a fateful decision: he would flee Prussia.

His intended destination was England, ruled by his maternal uncle George II. England was perceived on the continent as relatively more liberal, perhaps offering a refuge where Frederick could pursue his intellectual and artistic interests, and potentially live a life less constrained by his father’s suffocating presence. Accompanying him in this desperate venture was his intimate friend, Hans Hermann von Katte.

The escape attempt was disastrously clumsy. They were apprehended near the border. The King’s fury knew no bounds. He seriously contemplated executing his own son for treason (desertion from the army). While international pressure and pragmatic concerns ultimately stayed his hand regarding the Crown Prince, his vengeance fell squarely on Katte. Frederick was imprisoned in the fortress of Küstrin.

There, in a calculated act of psychological torture, Frederick William I forced his son to watch from his cell window as Hans Hermann von Katte, his closest companion, was beheaded in the courtyard below.

The image is haunting: the young prince, powerless, witnessing the brutal execution of his friend, a death directly resulting from their shared attempt to escape his father’s tyranny. The precise nature of Frederick and Katte’s relationship remains debated – was it an intense, loyal friendship forged in shared adversity, or did it encompass a deeper, romantic or physical intimacy? We cannot know for certain. But Katte’s death, orchestrated by his father, undeniably scarred Frederick profoundly.

It was a brutal lesson in the consequences of defiance and the lethal potential of intimacy in his world.

Following this trauma, Frederick outwardly submitted to his father’s will. He agreed to a politically expedient marriage in 1733 with Elisabeth Christine of Brunswick-Bevern, a princess he found dull and intellectually incompatible.

Frederick performed his military duties, biding his time. But the inner fire – his love for music, philosophy, and perhaps, for the company of men – was not extinguished. It was merely banked, waiting for the day he would finally be free from his father’s shadow.

When Frederick William I died in 1740, the 28-year-old Frederick ascended the throne. The kingdom was his. The constraints of his youth were gone.

Now, he could begin to shape his world, and his court, according to his own desires.

–

Mars Without Venus - The Secret of Sanssouci

“Or do you not know that the unrighteous will not inherit the kingdom of God? Do not be deceived: neither the sexually immoral, nor idolaters, nor adulterers, nor men who practice homosexuality, … will inherit the kingdom of God.”

Paul of Tarsus, 1 Corinthians 6:9–10

Upon his father’s death in 1740, Frederick II became King in Prussia (later King of Prussia).

The cage door had sprung open. The years of enforced conformity, public humiliation, and secret artistic pursuits under the Soldier King’s iron fist were over. Now, Frederick was master of his own destiny and that of his burgeoning kingdom.

One of his first, and most telling, acts was to create distance – physical and emotional – from the wife his father had forced upon him.

Elisabeth Christine, the dutiful but uninspiring Duchess of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel-Bevern, had served her purpose in the dynastic game. Frederick had done his duty by marrying her. Now, as King, he effectively sidelined her. While she retained her title as Queen, she was largely relegated to Schönhausen Palace near Berlin. Frederick rarely visited her, and she was pointedly excluded from his beloved sanctuary, Sanssouci Palace in Potsdam, which he began constructing in 1745. Sanssouci, meaning “without worry” or “carefree,” was to be his space, a private retreat dedicated to his personal interests – music, philosophy, conversation, and the company of his chosen circle.

And that circle was overwhelmingly, almost exclusively, male.

Sanssouci was conceived not as a grand state palace for pomp and ceremony, but as an intimate villa, a maison de plaisance. Its scale was relatively modest, its style the light, elegant Rococo Frederick favoured, a stark contrast to the Baroque bombast preferred by many contemporary monarchs. It was here, surrounded by his books, his flute, his Italian greyhounds (whom he adored, famously requesting to be buried beside them on the palace terrace), and his male friends, that Frederick spent his summers, escaping the formalities of Berlin and the burdens of rule.

The atmosphere Frederick cultivated at Sanssouci and the nearby New Palace (Neues Palais, built after the Seven Years’ War) was one of intellectual ferment and cultivated companionship.

He hosted evening gatherings known as the “Round Table” (Tafelrunde), modelled loosely on Arthurian legend but populated by philosophers, writers, military officers, and artists – figures like Voltaire (during his tumultuous stay in Prussia), the Marquis d’Argens, the mathematician Maupertuis, and various favoured military men.

Conspicuously absent, by design, were women.

Frederick made little secret of his aversion to female company in intellectual or social settings, often making cuttingly misogynistic remarks. While some degree of misogyny was common in the era, Frederick’s seemed particularly pronounced, bordering on outright disdain. He famously referred to his court as a place where “no skirts” were welcome.

This deliberate exclusion of women, coupled with his estrangement from his wife and the intensity of his relationships with certain men, inevitably fuelled speculation. Had Frederick, traumatised by his father and disinterested in his Queen, simply sworn off intimate relationships altogether, sublimating his energies into war, statecraft, and the arts? Or had he found companionship and perhaps intimacy elsewhere, within his carefully curated male world?

Rumours spread fast through Europe – and during Frederick’s lifetime the phrase les Potsdamistes was used widely to describe homosexual courtiers.

In taking the throne in 1740, Frederick also finally put to use the great army that his father had created – marching into Austria-controlled Silesia as an affront to that ‘big German power’. The same Austria that had pushed his father towards marrying Frederick to the Duchess of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel-Bevern but also, equally as consequential to the young Prince, convinced Frederick William I to spare Frederick after his failed escape to London, and instead execute his companion, von Katte.

While not expanding his Kingdom, or out settling old scores, Frederick would occupy himself by lavishing attention on male companions.

Two figures stand out among Frederick’s consorts, men who received extraordinary favour and intimacy, during these early years of his rule: Michael Gabriel Fredersdorf and Francesco Algarotti.

Fredersdorf’s story is remarkable. He entered Frederick’s service as a young soldier and valet during the Crown Prince’s confinement at Küstrin following the failed escape attempt. He quickly gained Frederick’s absolute trust and affection. Upon becoming King, Frederick elevated Fredersdorf far beyond his humble origins. He became the King’s private treasurer, effectively controller of his personal finances, manager of his estates, and general factotum. More significantly, he was Frederick’s constant companion, his confidante, the man who knew the King’s moods and secrets. At Sanssouci, Fredersdorf’s rooms were strategically placed directly adjacent to the King’s library and study, signifying privileged access. Frederick showered him with gifts, wealth, and influence, making him one of the most powerful men at court, albeit operating largely behind the scenes. Their closeness was palpable, leading inevitably to rumours about the true nature of their bond.

Was Fredersdorf merely a loyal servant and friend, or something more? The surviving correspondence, while often affectionate, remains ambiguous, written in the coded language of the time.

Count Francesco Algarotti was a different kind of favourite. A charming, erudite Italian polymath – writer, art connoisseur, scientist – Algarotti captivated Frederick during a visit to Prussia in 1739 before Frederick became King. Besides being exact contemporaries (both were born in 1712), both had long been admirers of poetry, philosophy, and the classics.

Once on the throne, Frederick invited Algarotti – whom he would lovingly refer to as the ‘Swan of Padua’ – back, showering him with honours, appointing him Court Chamberlain, and awarding him the prestigious Order of Merit.

Perhaps most immediately telling of their closeness was the trip to two took in 1740 to Frederick’s coronation. It was tradition for the Prussian King’s, since Frederick’s grandfather – Frederick III – to travel to Königsberg from Berlin for the royal coronation.

When Fredrick III crowned himself he took with him 1800 carriages and 30,000 horses. When Fredrick he travelled in a single carriage, with only Algarotti as his companion.

The correspondence between Frederick and Algarotti was effusive, filled with intellectual sparring and declarations of deep affection. Frederick clearly idealised Algarotti as a representative of the sophisticated culture he admired. He relied on Algarotti’s taste, sending him to Italy to acquire artworks for the royal collections. While Algarotti’s stays in Prussia were intermittent, his place in Frederick’s esteem was secure. Again, the precise nature of their relationship is debated – intense intellectual kinship, certainly; romantic or physical intimacy, possibly, but unproven.

Shortly after the Königsberg trip, Frederick penned a poem for Algarotti, entitled ‘The Orgasm’. The original manuscript, owned by Algarotti, was acquired by German Emperor William II and placed in the Berlin archives in 1894 – only to be rediscovered in 2011.

“From Königsberg to Monsieur Algarotti, Swan of Padua

This night, vigorous desire in full measure,

Algarotti wallowed in a sea of pleasure.

A body not even a Praxitiles fashions

Redoubled his senses and imbued his passions

Everything that speaks to eyes and touches hearts,

Was found in the fond object that enflamed his parts.

Transported by love and trembling with excitement

In Cloris’ arms he yields himself to contentment

The love that unites them heated their embraces

And tied bodies and arms as tightly as laces.

Divine sensual pleasure! To the world a king!

Mother of their delights, an unstaunchable spring,

Speak through my verses, lend me your voice and tenses

Tell of their fire, acts, the ecstasy of their senses!

Our fortunate lovers, transported high above

Know only themselves in the fury of love:

Kissing, enjoying, feeling, sighing and dying

Reviving, kissing, then back to pleasure flying.

And in Knidos’ grove, breathless and worn out

Was these lovers’ happy destiny, without doubt.

But all joy is finite; in the morning ends the bout.

Fortunate the man whose mind was never the prey

To luxury, or grand airs, one who knows how to say

A moment of climax for a fortunate lover

Is worth so many aeons of star-spangled honour.”

A clear reference to some kind of physical event that had occurred between the pair? Or playful titillation between two men who were well-schooled in the homoeroticism of the classical world?

Beyond these personal relationships, the very fabric of Frederick’s private world, particularly Sanssouci and the New Palace, seems infused with subtle, yet deliberate, references to themes of male beauty, companionship, and even same-sex love, often drawn from the classical antiquity he so admired.

One striking example is a particular bronze statue Frederick acquired.

In the 18th century, it was identified – at least by Frederick personally – as Antinous, the beloved of Emperor Hadrian. Unlike his usual practice of acquiring antiquities in bulk or as established collections, Frederick purchased this piece as a one-off, suggesting significant personal value. Standing prominently outside his office window at Sanssouci, the beautiful youth served as a potent symbol. Given Frederick’s known admiration for Hadrian, and the well-understood story of Hadrian’s passionate love for Antinous, the statue could be interpreted merely as an appreciation of classical art.

The myth surrounding Antinous, however, is several centuries younger than the acquired sculpture, which was cast in the early Hellenistic period.

Regardless, historians suggest a deeper, more personal resonance. Could the image of the tragically lost beloved have reminded Frederick of his own youthful loss – the execution of Hans Hermann von Katte? Could it also have served as a quiet, coded affirmation of the validity and beauty of love between men, embodied by the deified favourite of a Roman Emperor?

In the context of Frederick’s world, Antinous was more than just a sculpture; he was a recognisable symbol of male homosexuality, particularly appealing to connoisseurs like Frederick.

Further evidence can be found in a significant building in Sanssouci Park.

Frederick commissioned the Temple of Friendship (Freundschaftstempel) ostensibly in memory of his favourite sister, Wilhelmine of Bayreuth.

Yet, the iconography chosen is intriguing.

Adorning the columns are four medallions depicting famous pairs of male friends from classical antiquity, celebrated for their unwavering loyalty and deep bonds: Orestes and Pylades, Nisus and Euryalus, Heracles and Philoctetes, and Theseus and Pirithous. While ostensibly celebrating friendship, the choice of exclusively male pairs, known from myths often laden with homoerotic undertones, in a space dedicated to intimate companionship seems deliberate.

It subtly elevates intense male relationships to a classical ideal.

Inside the New Palace, Frederick’s grander Potsdam residence built to showcase Prussia’s power after the Seven Years’ War, similar themes emerge in prominent artworks.

In the Blue Antechamber, leading to Frederick’s private apartments, hangs Pompeo Batoni’s large canvas, Thetis Entrusting Chiron with the Education of Achilles. While depicting a scene from mythology, the focus on the muscular male figures and the theme of male mentorship resonates with classical ideals Frederick admired.

More explicit is the ceiling fresco in the opulent Marble Hall, the palace’s main state room, by Charles-Amédée-Philippe van Loo: The Induction of Ganymede in Olympus.

The myth of Ganymede, the beautiful Trojan youth abducted by Zeus (in the form of an eagle) to be his lover and cupbearer on Olympus, is one of the most overt classical stories of same-sex desire among the gods. Placing this scene in such a prominent position, at the very heart of his representational palace, is a bold statement.

It uses classical mythology, a safe and accepted artistic subject, to display a theme that, in contemporary terms, was deeply taboo.

These artistic and architectural choices, combined with Frederick’s personal relationships and known aversion to conventional married life, paint a compelling picture. He seems to have consciously constructed a world at Sanssouci and Potsdam that reflected his personal tastes and perhaps his deepest inclinations.

It was a world where male companionship, intellectual pursuits, and classical ideals reigned supreme, a world pointedly designated “without worry” – perhaps meaning without the worries imposed by societal expectations of marriage, heteronormativity, and female presence.

It was a realm fit for Mars, the god of war (representing Frederick’s military and state duties), but pointedly, a realm “without Venus,” the goddess of conventional love and femininity.

The historian Tim Blanning addresses the difficulty surrounding this topic directly: “Frederick’s homosexuality is a subject that was once taboo, remains fraught, but is too important to be ignored. Reluctance to accept it has been justified by the allegedly anachronistic character of the concept, for the word ‘homosexual’ and its cognates were late nineteenth-century inventions.”

Blanning argues, however, that while the term is modern, the phenomenon it describes – erotic and emotional attraction primarily or exclusively towards members of the same sex – clearly existed and is relevant to understanding Frederick.

The clues are embedded in the life he lived, the company he kept, and the private world he meticulously crafted for himself at Sanssouci.

It was a world designed for a king who, perhaps like the Roman emperor he admired, found beauty, companionship, and maybe even love, primarily among men.

Gaying With The Times - Of Erastes & Eromenos

“They sleep with their loved ones, yet stations them next to themselves in battle … with them (Eleians, Thebans) it’s a custom, with us a disgrace … placing your loved one next to you seems to be a sign of distrust … The Spartans … make our loved ones such models of perfection that even if stationed with foreigners rather than with their lovers they are ashamed to desert their companion.”

Xenophon, Symposium

The question of Frederick the Great’s sexuality is fraught with historical static.

The terminology itself is anachronistic; the concepts of ‘gay’ or ‘homosexual’ as identity markers being inventions of the late 19th century.

To apply them retrospectively requires care, sensitivity, and an understanding of the vastly different social and cultural landscape Frederick inhabited. Yet, the evidence – circumstantial, suggestive, coded, but persistent – demands examination. It hints at a private life starkly at odds with the expected norms of royalty, a life lived in the shadow of condemnation but perhaps finding expression in intense male friendships, artistic symbolism, and carefully curated spaces.

To understand the whispers surrounding Frederick, we must first step back, far back, beyond the powdered wigs and formal courts of 18th-century monarchs, to the very foundations of Western thought on love, desire, and relationships, specifically between men – to Classical Civilisation.

For it was in the sun-drenched landscapes of ancient Greece and the marble halls of Rome that collegiate attitudes towards same-sex intimacy were forged, attitudes that Frederick, a devoted student of the Classics, knew intimately.

Ancient Greece, particularly Athens, presented a complex picture.

While not condoning all forms of same-sex relations, it institutionalised a specific form: pederasty. This was a socially acknowledged relationship between an older man (the erastes, typically in his 20s or 30s) and an adolescent boy (the eromenos, usually between puberty and the growth of his first beard). Ideally, this was framed not just by physical desire but by mentorship, education, and the transmission of civic virtue. Plato’s Symposium, a philosophical dialogue Frederick would have read, explores the nature of Eros (love/desire) in its various forms, including the love between men, elevating it as potentially leading towards philosophical enlightenment.

Military culture also embraced intense male bonds.

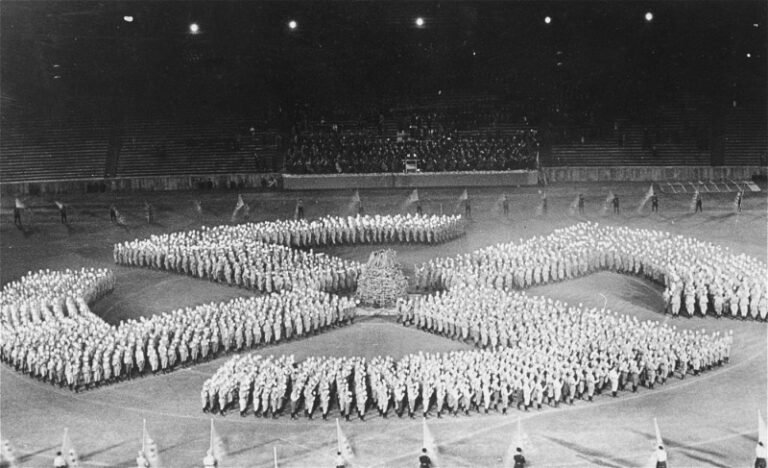

The legendary Sacred Band of Thebes, an elite fighting force composed of 150 pairs of male lovers, was renowned for its ferocity, the idea being that soldiers would fight more bravely and refuse to desert their beloved companions.

The historian Xenophon, quoted in the reference notes, reflects this thinking: “They sleep with their loved ones, yet station them next to themselves in battle… placing your loved one next to you seems to be a sign of distrust… The Spartans… make our loved ones such models of perfection that even if stationed with foreigners rather than with their lovers they are ashamed to desert their companion.”

This idealisation of male pairs in a martial context – Achilles and Patroclus from the Trojan War, Orestes and Pylades famed for their loyalty – provided a powerful classical precedent for intense, devoted male relationships.

Rome inherited much from Greece, but its attitudes towards same-sex relations were subtly different. While pederasty wasn’t institutionalised in the same way, relationships between men certainly occurred, particularly among the elite. Roman society was arguably more concerned with the roles played in a sexual act than the genders involved. For a freeborn Roman man, taking the dominant, ‘active’ role with a social inferior (like a slave or a foreigner), whether male or female, was generally acceptable. However, adopting the ‘passive’ role was seen as deeply shameful, associated with effeminacy and a loss of masculine virtue (virtus). Bisexuality appears to have been relatively common and unremarkable, provided these social hierarchies and role expectations were maintained.

One towering Roman figure looms large in this context, someone Frederick deeply admired: Emperor Hadrian.

Reigning from 117 to 138 AD, Hadrian was known as one of the “Five Good Emperors,” a builder (Hadrian’s Wall in Britain), administrator, and intellectual. He was also known for his passionate love for a beautiful young Greek man from Bithynia named Antinous. Their relationship, lasting several years until Antinous’s mysterious drowning in the Nile around 130 AD, was intense and public. Devastated by the loss, Hadrian took the extraordinary step of deifying Antinous, founding the city of Antinoopolis in his honour and commissioning countless statues that immortalised his youthful beauty.

These images of Antinous became ubiquitous across the Empire, a poignant testament to Hadrian’s grief and love. The story of Hadrian and Antinous provided a powerful, high-profile example of same-sex love at the very pinnacle of Roman power, a story that resonated through the centuries and found particular purchase in the 18th century, not least with Frederick himself.

However, the classical world’s relative openness, nuanced as it was, did not last.

The rise of Christianity brought a seismic shift. The Abrahamic religions viewed procreation as the primary purpose of sex within marriage. Same-sex acts, seen as non-procreative and outside this framework, were increasingly condemned. The writings of Paul the Apostle, particularly his Epistle to the Corinthians, became foundational texts for this view: “Or do you not know that the unrighteous will not inherit the kingdom of God? Do not be deceived: neither the sexually immoral, nor idolaters, nor adulterers, nor men who practice homosexuality [often translated from terms like arsenokoitai and malakoi, whose precise meanings are debated but were interpreted as referring to same-sex acts], … will inherit the kingdom of God.” (1 Corinthians 6:9–10).

This theological condemnation gradually translated into legal prohibition across Europe.

By the time Frederick the Great ascended the throne, the classical world’s complex tapestry of attitudes had been replaced by a starker reality: “sodomy,” a broad term encompassing various non-procreative sexual acts, including those between men, was a crime, often punishable by death.

It was considered a sin against God and nature, whispered about in fear and disgust.

This, then, was the world Frederick inherited: a classical past offering models of intense male bonds and even imperial same-sex love, juxtaposed against a present where such inclinations were religiously damned and legally perilous.

It is within this charged atmosphere, this tension between classical ideals and contemporary constraints, that we must examine the life of Prussia’s greatest king and the enduring question of his true desires. Did he see himself reflected in the heroes of antiquity or the tragic love of Hadrian? And how did he navigate these dangerous waters in the rigid, militaristic court of Prussia?

The answers, or at least the clues, lie in his tumultuous youth, his carefully constructed sanctuary at Sanssouci, and the company he kept.

The Famous Gays of Frederick the Great’s World

“Frederick’s homosexuality is a subject that was once taboo, remains fraught, but is too important to be ignored. Reluctance to accept it has been justified by the allegedly anachronistic character of the concept, for the word ‘homosexual’ and its cognates were late nineteenth-century inventions.”

Tim Blanning, author of Frederick the Great

Frederick the Great did not exist in a historical vacuum.

Nor should his actions – or identity – be judged in one.

His interests, his reading, and his awareness of the world around him meant he was undoubtedly familiar with other prominent figures, both historical and contemporary, whose lives diverged from conventional heterosexual norms, or who, like himself, attracted speculation about their private inclinations.

Examining these figures helps contextualise Frederick’s own situation, demonstrating that while same-sex desire was condemned, it was a known, if often unspoken, aspect of the European elite landscape. These examples provided models, cautionary tales, and perhaps even a sense of shared, albeit hidden, identity.

Pride of place among historical figures relevant to Frederick’s potential self-perception belongs, once again, to Emperor Hadrian and his beloved Antinous. As we’ve seen, Frederick acquired a statue identified as Antinous and displayed it prominently. His admiration for Hadrian, the philosopher-emperor and builder, was well-documented. The story of Hadrian’s profound love for the young Greek, his grief, and his subsequent deification of Antinous resonated powerfully in the 18th century among cognoscenti. Antinous, immortalised in countless sculptures salvaged from antiquity, became, as noted, a potent symbol of idealized male beauty and same-sex love.

For connoisseurs like Frederick, collecting or displaying images of Antinous could be a subtle, coded way of signalling an appreciation for this classical precedent of imperial homosexual love. The sheer volume of Antinous imagery surviving – more than any other classical figure except Augustus and Hadrian, according to classicist Caroline Vout – speaks to the enduring power of this story and its artistic legacy, a legacy Frederick actively participated in preserving and displaying.

Closer to Frederick’s own time, and a figure often compared to him, was Prince Eugene of Savoy (1663-1736). A brilliant military commander of French origin, Eugene offered his services to the Holy Roman Emperor after being slighted by King Louis XIV of France. He became one of the most successful generals of his age, famously helping lift the Ottoman Siege of Vienna in 1683 and achieving numerous victories against the French in the War of the Spanish Succession. Like Frederick, Eugene was a complex figure – a warrior, a statesman, a renowned art collector, and the builder of the magnificent Belvedere Palace in Vienna.

Crucially, Eugene never married and was famously reputed to be uninterested in women. He reportedly quipped that women were a hindrance in war and that a soldier should remain unattached. This led to him being dubbed “Mars without Venus” – a moniker that could equally apply to Frederick. Rumours of homosexuality followed Eugene throughout his life, originating, according to some accounts, from his youth at the French court. The notorious gossip-monger Elizabeth Charlotte, Duchess of Orléans (known simply as “Madame,” and sister-in-law to Eugene’s adversary Louis XIV), wrote scathingly about Eugene’s alleged youthful “depravity” with lackeys and pages, claiming this was why he was denied a position in the Church.

Eugene himself seems to have been aware of these rumours and dismissed them contemptuously in his memoirs as inventions from Versailles. His biographer Helmut Oehler attributed Madame’s comments primarily to personal resentment after Eugene had repeatedly defeated French armies. While concrete proof of homosexual activity is lacking, the persistent rumours, Eugene’s lifelong bachelorhood, his “Mars without Venus” reputation, and his known circle of close male associates created a strong perception.

As a towering military and cultural figure whose career overlapped Frederick’s youth and early reign, Eugene provided a powerful contemporary example of a highly successful, unmarried leader operating within an exclusively male milieu, dogged by similar whispers to those that would later surround Frederick. Frederick, an avid student of military history and contemporary affairs, would certainly have known of Eugene’s reputation.

Another monarch admired by both Frederick and his correspondent Voltaire, and whose life bore parallels to Frederick’s potential situation, was Charles XII of Sweden (1682-1718). Charles was a fascinating, almost mythical figure – a warrior king who ascended the throne at 15 and spent most of his reign at war, leading the Swedish Empire in the Great Northern War against a coalition led by Peter the Great of Russia. He was renowned for his personal bravery, austerity, and autocratic rule.

The French philosopher, Voltaire, wrote a famous biography portraying him in a heroic light.

Like Eugene and Frederick, Charles XII never married and fathered no children. His entire adult life was consumed by military campaigns. He actively resisted attempts to arrange marriages for him, stating he was, in a sense, “married” to the military life and would consider matrimony only once peace was secured – a peace that never truly came for him. He died young, shot dead under mysterious circumstances while inspecting trenches during an invasion of Norway.

Charles’s lack of female companionship and apparent chastity inevitably led to speculation. Some attributed it to deep religious conviction or sheer focus on warfare. Others, however, suspected different reasons.

Rumours even circulated that he might be a hermaphrodite, a theory disproven only in 1917 when his coffin was opened.

More persistent were suggestions of homosexuality.

Historians like Tim Blanning and Simon Sebag Montefiore lean towards this interpretation. Evidence is scant, but includes a letter suggesting Charles felt a particular closeness to a handsome young German prince, Maximilian Emanuel of Württemberg-Winnental, whom Charles described as “very pretty.” As with Eugene, definitive proof is absent. Counterarguments suggest the relationship with Württemberg was merely teacher-pupil, and that Charles simply suppressed any sexual urges he might have had.

Regardless of the reality, Charles XII represented another powerful archetype relevant to Frederick: the brilliant, unmarried, autocratic military hero operating in a world largely devoid of women, whose intense focus and lack of conventional relationships led to public speculation about his sexuality. Voltaire’s admiration, shared by Frederick, cemented Charles’s image as a heroic, if tragic, figure. He embodied, as one analysis puts it, “the conjunction of military and royalty, victory and calamity, together with a world without women and homosexual orientation.”

These figures – the classical emperor Hadrian openly loving Antinous, the contemporary general Prince Eugene known as “Mars without Venus,” and the admired warrior-king Charles XII living a life “married” to the military – formed part of the cultural landscape Frederick inhabited.

They demonstrated that deviation from the expected path of marriage and heterosexual relations, while risky and subject to gossip, was not unknown among the powerful.

They provided historical and contemporary parallels, models of leadership combined with unconventional personal lives. Whether Frederick consciously saw himself in their mould is impossible to say. But their stories, reputations, and the speculation surrounding them undoubtedly contributed to the atmosphere in which Frederick navigated his own preferences and constructed his own private world.

They showed that other men of power and renown had trod similar paths, embraced intense male bonds, or faced similar questions about their deepest affections, offering precedents – both inspiring and cautionary – for a king like Frederick, ruling Prussia from his male-dominated sanctuary at Sanssouci.

**

Conclusion

So, was Frederick the Great gay? After sifting through the historical fragments – the traumatic youth under a tyrannical father, the pointed distance from his wife, the intense bonds with male companions like Fredersdorf and Algarotti, the carefully curated male world of Sanssouci, the suggestive iconography drawn from classical antiquity, and the parallels with other historical figures shrouded in similar speculation – can we definitively answer this most personal of questions about Prussia’s most famous king?

The honest answer remains elusive, shrouded in the ambiguities of the past and the limitations of evidence. We have no explicit confession, no unambiguous love letters, no eyewitness account that settles the matter beyond doubt.

History rarely offers such convenient certainties, especially concerning the private lives of those who lived under the shadow of severe social and legal condemnation.

To expect a “smoking gun” regarding Frederick’s sexuality is perhaps to misunderstand the constraints and codes of the 18th century.

What we do have is a significant accumulation of circumstantial evidence, a pattern of behaviour, and a series of choices that strongly suggest Frederick’s primary emotional, intellectual, and likely erotic interests were directed towards men. His documented aversion to women in his intimate circle, his lifelong avoidance of his wife after the initial duty was done, the extraordinary favour and intimacy shown to men like Fredersdorf, the deliberate creation of Sanssouci as a male sanctuary, and the pointed inclusion of homoerotic classical themes like Antinous and Ganymede in his art collections – all these point in a consistent direction.

In the absence of a direct admission from Frederick, it is not possible to say when a Platonic relationship became Socratic.

The evidence on the whole, however, leans heavily towards a Frederick whose world, emotionally and perhaps physically, revolved around men, a Prussian identity forged not just in battle and philosophy, but in the quiet complexities of unspoken desire.

***

If you’ve enjoyed reading this article, consider booking one of our private guided tours of Berlin.

HISTORICAL ARTICLES

Mythbusting Berlin

Are There Any Nazi Statues Left In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

Visitors to Berlin often arrive expecting to find the physical remnants of the tyranny of the 20th century still standing – statues of dictators, triumphal arches, or bronze idols. Instead, they often find none. The stone symbols and statues of the Third Reich are still gazing down on them, however, hiding in plain sight. But why are there no statues of Hitler? Did the Allies destroy them all in 1945, or is the truth stranger

Could The Western Allies Have Captured Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

To contemplate a Western Allied capture of Berlin in 1945 is to challenge the established endgame of the Second World War. What was the true military and logistical feasibility of a Western Allied assault on the Nazi capital? What factors truly sealed Berlin’s fate, and what might have changed had the Allies pushed eastward?

Answering these questions means delving into the complex interplay of logistics, political maneuvering, and the competing visions for a post-war world

Did Any Of The Rothschild Dynasty Die In The Holocaust? – Mythbusting Berlin

The Rothschild name is synonymous with immense wealth, influence, and persistent conspiracy theories—especially during the era of Nazi Germany. Often targeted by antisemitic propaganda, the family’s survival during World War II has sparked myths about their supposed immunity from Nazi persecution. But did any Rothschild family member actually perish in the Holocaust? This article explores that compelling question, unraveling historical misconceptions and revealing the reality behind one of Europe’s most famous dynasties.

Did Frederick The Great Introduce The Potato To Germany? – Mythbusting Berlin

One of the more bizarre claims to fame attributed to the first King of Prussia is that the man who would go down in history known as Frederick the Great introduced the potato to Germany during his reign back in the 1700s. This starchy root vegetable has undoubtedly become a staple part of German cuisine – an essential addition to any plate of Schnitzel, Schweinshaxn, and Königsberger Klopse – however, whether Frederick the Great is

Did Hitler Escape To Argentina In 1945? – Mythbusting Berlin

Although Nazi leader, Adolf Hitler, certainly remains an inescapable figure, could there be any truth to the story of his escape to Argentina in 1945? That the most wanted man on earth could simply vanish, to spend the rest of his life peacefully in South American obscurity captivates imaginations. Yet, despite numerous investigations, this tale persists primarily as myth—fueled by speculation, hearsay, and conspiracy theories.

Did Hugo Boss Design The Nazi Uniforms? – Mythbusting Berlin

The idea that Hugo Boss – the man whose name now adorns expensive suits and fragrances – was the creative genius behind the Nazi uniforms suggests a terrifying collision of haute couture and holocaust – a marriage of high style and high crimes. The image is striking: a German tailor sketching the ultimate villain’s costume. But history, as usual, is far messier, more bureaucratic, and more banal than the internet memes suggest. To understand who

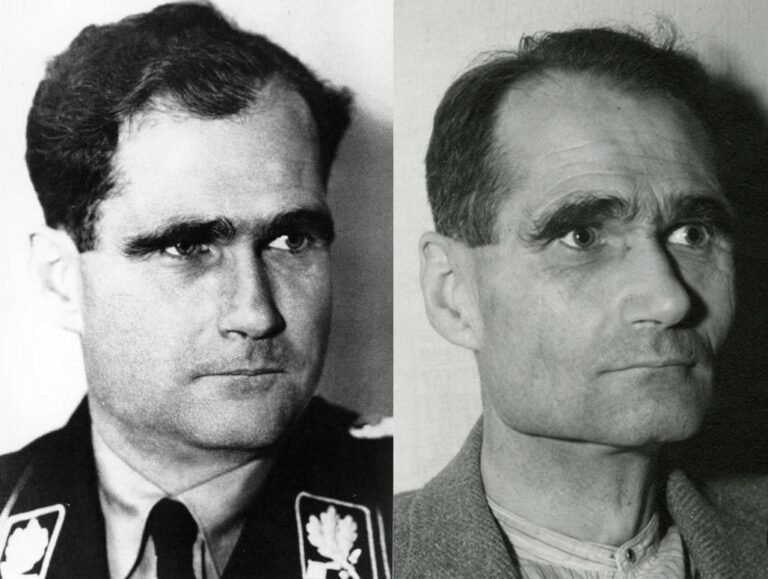

Did Rudolf Hess Really Commit Suicide? – Mythbusting Berlin

On a summer’s day in 1987, the last Nazi war criminal of the Nuremberg trials was found dead in a prison built for hundreds, yet for two decades, housed only him. The official verdict was suicide, a straightforward end to a life defined by fanaticism, delusion, and contradiction.

But the simplicity of the report belied the complexity of the man and the 46 years he had spent in Allied custody. In the meticulously controlled

Did The Nazis Develop Nuclear Weapons? – Mythbusting Berlin

The Nazi obsession with super-weapons became so serious in the closing stages of the Second World that Adolf Hitler personally believed that such ‘Wunderwaffen’ both existed in a usable form – and would save the country from defeat. Had the Nazis managed to develop nuclear weapons by 1945 – the outcome of the war would surely have been different. But how close were Hitler, Himmler, and his henchmen to developing an A-bomb?

Did The Nazis Invent Decaf Coffee? – Mythbusting Berlin

Persistent rumors claim that Nazis preferred their coffee anything but pure, leading some to wonder if they might have influenced the development of decaffeinated coffee. Although decaf was already widely available across Europe by the mid-20th century, speculation continues: could the Nazis really have played a role in popularizing—or even discovering—this caffeine-free alternative, or is this simply another caffeinated conspiracy cooked up to sensationalize an ordinary historical detail?

Did The Nazis Invent The Bicycle Reflector? – Mythbusting Berlin

The fruits of wartime ingenuity are plenty – so many, in-fact, that it has become somewhat of a worn cliche that as the guns start firing the innovators get to work, often solving problems while providing more problems for the enemy to overcome.The kind of progress that results in the production of newer improved, more lethal weapons, such as to increase the chances of victory.

Did The Nazis Run The Largest Counterfeiting Operation In History? – Mythbusting Berlin

During the Second World War the Nazis masterminded an astonishing plot to destabilise Britain by flooding its economy with counterfeit banknotes. Crafted in secret by concentration camp prisoners, this forged fortune became the most ambitious counterfeiting operation ever attempted. But was it history’s largest? Dive into the extraordinary tale of Operation Bernhard,

rife with deception, survival, and intrigue—revealing the truth behind one of the Third Reich’s most audacious schemes and its surprising legacy.

Did The Second World War End In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

When is a war ever truly over? When the last shot is fired in anger would seem like the best measure. Rarely, though, is it possible to gain insight into such a moment.

Remarkably, a record still exists of such a moment at the end of the First World War on the Western Front. A seismic register and recording of the last belching battery of British guns firing artillery across no-man’s-land, followed by a profound

Did The Spanish Flu Pandemic Help The Nazis Take Power? – Mythbusting Berlin

The devastating Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918-1919 struck amid Germany’s post-war turmoil, compounding social instability, economic hardship, and widespread political disillusionment. Could this catastrophic health crisis have indirectly paved the way for Nazi ascension? While often overshadowed by war and revolution, the pandemic’s profound psychological and societal impacts arguably contributed to the perfect storm, enabling extremist ideologies—including Nazism—to gain popularity and ultimately seize power in a fractured Germany.

Have Adolf Hitler’s Remains Been DNA Tested? – Mythbusting Berlin

In the smouldering ruins of Berlin in 1945, the world’s most wanted man vanished. Did Adolf Hitler, as official history attests, die by his own hand in the Führerbunker? Or did he escape, fuelling a thousand conspiracy theories that have echoed for decades? For years, the Soviets claimed to hold the gruesome proof of his death: a skull fragment and a set of teeth, locked away in Moscow archives. But in an age of definitive

How Did The Nazi Concentration Camps Differ From The Soviet GULAG?

The Nazi concentration camps and Soviet Gulag system have often been conflated in popular imagination—twin symbols of twentieth-century totalitarian horror. Yet the two systems operated on fundamentally different principles. One extracted labor to fuel industrialisation while accepting mass death as collateral damage; the other evolved into purpose-built machinery of genocide. Understanding these distinctions isn’t merely academic—it reveals how different ideologies produce different atrocities, and why Germany and Russia reckon with these legacies so differently today.

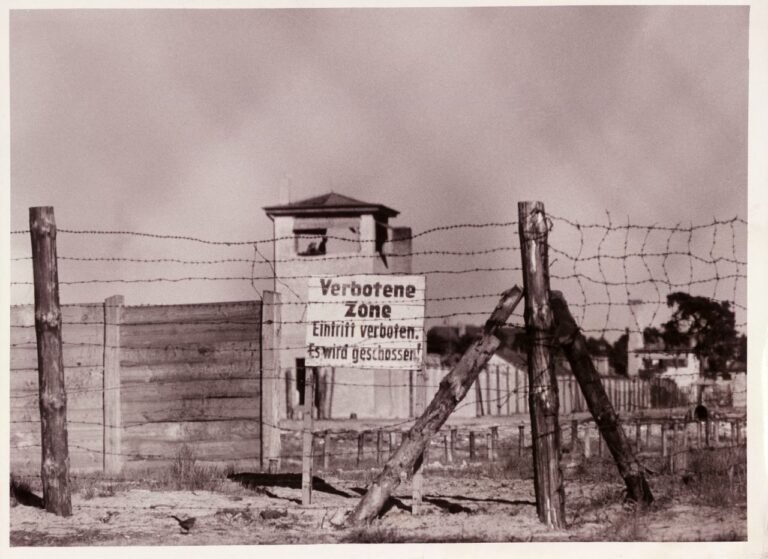

How Long Did It Take To Build The Berlin Wall? – Mythbusting Berlin

It is one of the most enduring images of the 20th century: a city divided overnight. The popular narrative tells us that Berliners went to sleep in a unified city and woke up in a prison. While the shock of August 13th 1961, was very real, the idea that the ‘Wall’ appeared instantly is a historical illusion. The physical scar that bisected Berlin was not a static creation, but a living, malevolent beast that evolved

How Many Assassination Attempts On Adolf Hitler Were There? – Mythbusting Berlin

Nazi leader, Adolf Hitler, projected an aura of invincibility, a man of destiny shielded by providence. But behind the carefully constructed image of the untouchable Führer lies a story of constant threat, of bombs that failed to detonate, and errant bullets that missed their mark. Unearth the hidden history of the numerous attempts on Hitler’s life as we explore the courage of those who tried to change the course of history and the devil’s luck

How Many Jews Died In The Holocaust? – Mythbusting Berlin

The answer to the question posed of how many Jews died in the Holocaust is a simple one: too many. That merely one death was an unforgivable obscenity is a fundamental and necessary realisation in understanding the capriciousness of this unparalleled racial genocide. To comprehend, however, the full number of Jews murdered in Europe by the Nazi regime in the 1930s and 1940s is a detective story of epic proportions: the evidence overwhelming, multifaceted, and

How Many People Died Trying To Escape East Germany? – Mythbusting Berlin

The image of the Berlin Wall is seared into our collective memory, a concrete symbol of Cold War oppression. We think of the daring escapes and the tragic deaths of those who failed. But that well-known number is only a fraction of the truth. The story of those who died trying to escape East Germany is far broader and more complex than most imagine, stretching along a thousand-kilometer border and out into the cold waters

How Old Is Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

A relatively new arrival in Europe, Berlin is over 1000 years younger than London, nevermind Rome or Athens, Jerusalem or Jericho. Just how old is Berlin though?

A question fraught with false assumptions and distortions – that has more often than not been answered with propaganda as it has with the cold hard truth.

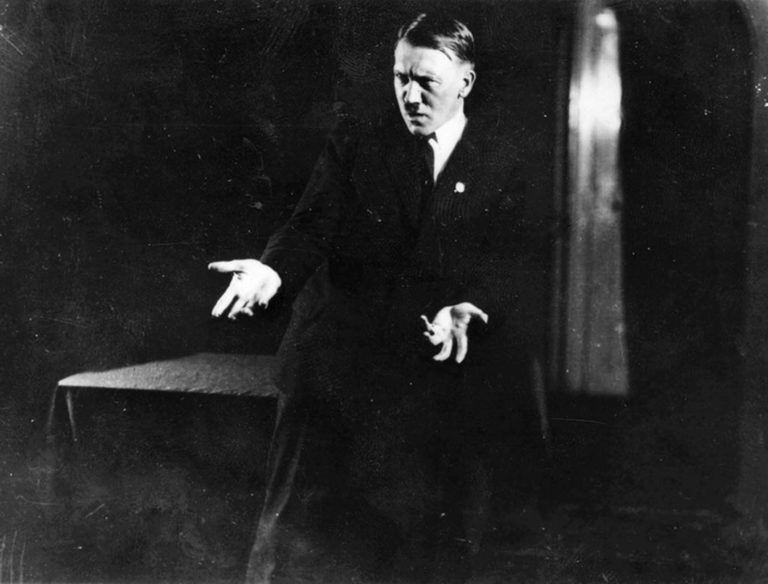

Was Adolf Hitler A Drug Addict? – Mythbusting Berlin

Solving the enigma of the ‘Führer’ has become a preoccupation for many, since the arrival of the Austrian-German onto the world stage – although moving beyond the mythology without falling into the trap of prejudically extrapolating on the psychopathography of Hitler or demonising so as to excuse his actions has proven problematic. What to make of the man who became more than the sum of his masks? The painter; the military dilettante, the mass murderer,

Was Adolf Hitler A Freemason? – Mythbusting Berlin

History abhors a vacuum, but adores a mystery. Such is the speculative fiction suggesting a secret allegiance behind the rise of the Third Reich – that the catastrophe of the Second World War was orchestrated from the shadows of a Masonic lodge. The image of Adolf Hitler—the drifter from Vienna turned dictator—as a covert initiate of the very brotherhood he publicly reviled, however, creates a paradox that collapses under scrutiny. As when we unlock the

Was Adolf Hitler Gay? – Mythbusting Berlin

In the shadowy corridors of Third Reich history, few questions provoke as much tabloid curiosity and scholarly exasperation as the sexuality of Adolf Hitler. For decades, rumors have swirled—whispered by political enemies in 1930s Munich, psychoanalyzed by American spies in the 1940s, and sensationalized by revisionist authors today. Was the dictator who condemned thousands of men to concentration camps for “deviant” behavior hiding a secret of his own? By peeling back the layers of propaganda,

Was Adolf Hitler Jewish? – Mythbusting Berlin

Was the dictator who orchestrated the murder of millions of European Jews secretly one of them? It is perhaps the darkest irony imaginable, a story whispered for decades in backrooms, bars, and conspiracy forums alike. The most-common rumour – the ‘Frankenberger Myth’ – suggests that Adolf Hitler’s paternal grandfather was Jewish, a secret so damaging it could have unraveled the entire Nazi regime. But where does this claim come from? And, more importantly, is there

Was Currywurst Invented In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

Explore the story behind what many consider Berlin’s most iconic snack—the ever-so-humble Currywurst. Often hailed as an enduring symbol of culinary creativity amid Cold War scarcity, this humble dish has inspired fierce debate about its true origin. But was it genuinely invented here in Berlin, or have proud locals simply adopted and elevated this spicy street-food favorite into legendary status all their own?

Was Fanta Invented By The Nazis? – Mythbusting Berlin

As one of the most secretive organisations in the world, the Coca Cola corporation refuses to share its secret recipe with anyone. Famously insisting only on shipping the base syrup of its drinks to plants around the world to be carbonated and distributed.

This combined with the trade limitations of the Second World War may have led to the introduction of one of the most popular soft-drinks in the world. But could it be true:

Was Frederick The Great Gay? – Mythbusting Berlin

Frederick II of Prussia, better known as Frederick the Great, is often remembered as the archetypal enlightened monarch – a brilliant military commander, patron of the arts, and learned philosopher. Yet behind the stern portraits of this 18th-century warrior-king lies a personal life long shrouded in intrigue and speculation. Intrigue around the king’s sexual orientation has persisted through the centuries, chiefly revolving around one question: Was Frederick the Great gay?

Was Henry Ford A Nazi? – Mythbusting Berlin

US auto tycoon, Henry Ford, holds the ignominious distinction of being the only American Adolf Hitler praised by name in his National Socialist manifesto: ‘Mein Kampf’. This was not, as it turns out, the only connection between Ford and the Party of Hitler, Himmler, and the Holocaust.

Ford’s overt affinity with the Third Reich reveals a troubling past. How deep these connections ran, and how consequential they were for both sides, is a chapter

Was The Colour Blue Invented In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

Tracing the true history of blue—from ancient Egyptian dyes to the accidental discovery of Prussian Blue in a Berlin lab. We’ll debunk myths about seeing blue, explore colonial indigo plantations, scale mountains with a cyanometer, and trace Van Gogh’s starry skies—all to answer one question: how did Berlin shape our understanding of the world’s rarest color?

Was The Döner Kebab Invented In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

Unlikely icon of immigrant success; fast food symbol of the working class; over-hyped midnight disco eat; or culturally appropriated cuisine? Its influence goes far beyond layers of seasoned meat and fresh vegetables stuffed into pita bread. But does Berlin deserve credit as the Döner Kebab’s true birthplace, or has the city merely refined and popularized a culinary tradition imported from elsewhere?

Was The Fall Of The Berlin Wall An Accident? – Mythbusting Berlin

On a seasonally crisp night in November 1989, one of the most astonishing events of the 20th century occurred. After twenty eight years, three months, and twenty eight days of defining and dividing the German capital, the Berlin Wall ceased to exist – at least in an abstract sense. Although the removal of this symbol of the failure of the East German system would take some time, its purpose – as a border fortification erected

Was The Nazi Party Democratically Elected? – Mythbusting Berlin

The myth persists that Adolf Hitler rose to power through popular democratic choice. Yet history reveals a darker, more complicated truth. Hitler’s ascent involved exploiting democratic institutions, orchestrating violence, propaganda, and political intrigue—not a simple election victory. Understanding how Germany’s democracy collapsed into dictatorship helps illuminate the dangerous interplay between public desperation, elite miscalculations, and extremist ambition, providing crucial lessons for safeguarding democracy today.

Were The Allied Bombings Of Germany War Crimes? – Mythbusting Berlin

The history of the Allied bombing of Germany during the Second World War still triggers fierce debate. Was reducing cities to rubble a necessary evil – justice from above in a just war – or an unforgivable crime? Can the intentional targeting of civilians ever be justified as militarily necessary?

In a conflict where all rules seemed to vanish, an even more pertinent question persists: by the very standards they would use to judge their

Were The Nazi Medical Experiments Useful? – Mythbusting Berlin

Before the Nazi period, German medicine was considered the envy of the world – a shining monument to progress. But deep within that monument, a rot was spreading, one which would collapse the entire structure into an abattoir. From the wreckage, we are left with a profoundly uncomfortable inheritance: a moral enigma wrapped in doctor’s whites.

What to make of the data, the images, and the terrible knowledge gleaned from unimaginable human suffering. Whether

What Are The Origins Of The Nazi Salute? – Mythbusting Berlin

A specter is haunting the modern mind, a gesture so charged with the dark electricity of history that its mere depiction can unleash a storm of controversy.

It is a simple movement: the right arm, stiff and straight, raised to the sky. But in that simplicity lies a terrifying power, a symbol of a regime that plunged the world into an abyss and a chilling reminder of humanity’s capacity for organised hatred.

This

What Are The Origins Of The Nazi Swastika? – Mythbusting Berlin

Long before the legions of the Third Reich marched beneath its stark, unnerving geometry, the swastika lived a thousand different lives. It was a symbol of breathtaking antiquity, a globetrotting emblem of hope and good fortune that found a home in the most disparate of cultures. To even begin to understand its dark 20th-century incarnation, one must first journey back, not centuries, but millennia.

What Are The Pink Pipes In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

A first-time visitor to Berlin could be forgiven for thinking the city is in the midst of a bizarre art installation. Bright pink pipes, thick as an elephant’s leg, climb out of the ground, snake over pavements, arch across roads, and disappear back into the earth. Are they part of a complex gas network? A postmodern artistic statement? A whimsical navigation system? These theories, all logical, are all wrong. The truth is far more elemental,

What Do The Colours Of The German Flag Symbolise? – Mythbusting Berlin

What does a flag mean? Is it merely a coloured cloth, or does it hold the hopes, struggles, and identity of a nation? The German flag, with its bold stripes of black, red, and gold, is instantly recognisable. But the story of its colours is a tumultuous journey through revolution, suppression, and reinvention. The common explanation for their symbolism is a simple, romantic verse, yet the truth is a far more complex and contested tale,

What Happened To Adolf Hitler’s Alligator? – Mythbusting Berlin

It is often said that you can tell a lot about a person by their relationship with animals; that owners often come to look and behave like their pets. Or is it perhaps more that people choose their pets to correspond to their personality? Nazi leader Adolf Hitler’s love of dogs, for example, is well documented but what is there to make of his relationship with reptiles?

What Happenened To The German Royal Family? – Mythbusting Berlin

When the smoke cleared over the trenches in November 1918, the German Empire had evaporated, and with it, the divine right of the Hohenzollern dynasty. Conventional wisdom suggests the family simply vanished into the sepia-toned obscurity of history books—exiled, forgotten, and irrelevant. But dynasties, like weeds in a landscaped garden, are notoriously difficult to uproot entirely. The story of the German royals did not end with the Kaiser’s flight to Holland; it merely shifted gears.

What Is The Difference Between Fascism & Nazism? – Mythbusting Berlin

While the terms ‘Fascist’ and ‘Nazi’ are often bandied around interchangeably as shorthand for tyranny – Italian fascism and German National Socialism were distinctly different beasts. Albeit ideological kin. One an ideology of state-worship, born from post-war chaos and national pride; the other built upon a fanatical, pseudo-scientific obsession with race. Two peas in the same totalitarian pod – twins in tyranny – more succinctly summarised as the Nazi chicken to the Fascist egg.

What Was Checkpoint Charlie? – Mythbusting Berlin

Checkpoint Charlie remains among Berlin’s most visited historical sites, famed worldwide for its significance during the Cold War. Originally established as a modest border-crossing point, it evolved dramatically over the decades into an international symbol of freedom, espionage, and intrigue. Today, critics and locals often dismiss it as little more than a tourist trap—Berlin’s Disneyland—but how exactly did Checkpoint Charlie get its peculiar name, and what truths hide behind its popularity?

What Was Prussia? – Mythbusting Berlin

Prussia’s legacy is both remarkable and contentious—once a minor duchy, it rose dramatically to shape modern European history. Renowned for military discipline, administrative efficiency, and cultural sophistication, Prussia was instrumental in uniting the German states, laying foundations for a unified Germany. But how did this kingdom, with its roots in Baltic territories, achieve such prominence, and why does its complex history continue to evoke admiration, debate, and occasional discomfort in Germany today?

What Was The Berlin Airlift? – Mythbusting Berlin

In the ruins of 1948, the silence of Berlin was not a sign of peace, but a held breath before a new catastrophe. The city, drowning in rubble and political intrigue, became the staging ground for the twentieth century’s most audacious gamble. While popular history remembers the chocolate parachutes and smiling pilots, the reality of the Berlin Airlift was a terrifying operational nightmare born from a ruthless currency war. It wasn’t just a humanitarian mission;

What Was The Socialist Kiss? – Mythbusting Berlin

It is one of the most curious and enduring images of the Cold War: two middle-aged, grey-suited men, locked in a fervent embrace, their lips pressed together in a kiss of apparent revolutionary passion. This was the ‘Socialist Fraternal Kiss’, a ritual that, for a time, seemed to encapsulate the unwavering solidarity of the Eastern Bloc.

But what was behind this seemingly intimate gesture? Was it a genuine expression of camaraderie, a piece of

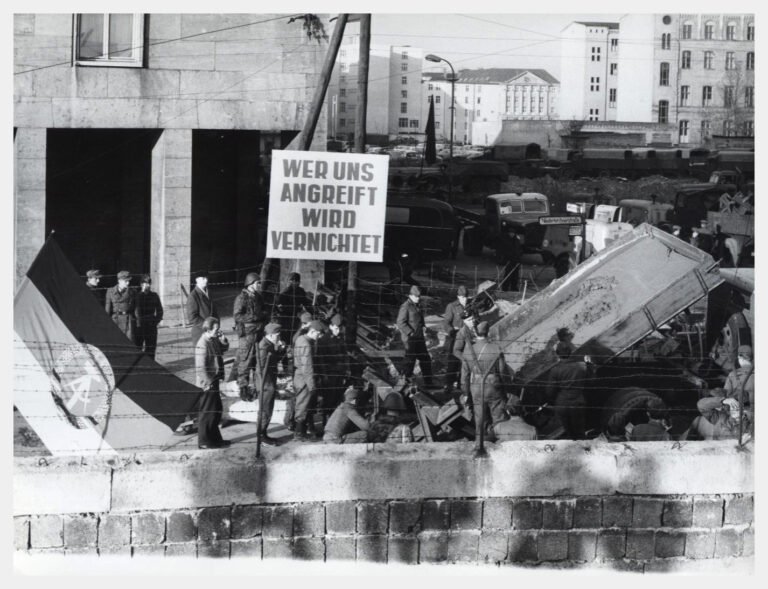

Who Built The Berlin Wall? – Mythbusting Berlin

One of the most common questions I have encountered from people curious about Berlin, and often so cryptically phrased. Who built the Berlin Wall? A simple five-word query, yet one that can be read one of two ways. More than thirty years since the ‘Fall of the Wall’, the story of its construction continues to baffle many who are mainly familiar with its existence through knowledge of its importance…

Who Really Raised The Soviet Flag On The Reichstag? – Mythbusting Berlin

One iconic photograph has come to symbolise the Red Army’s victory over Nazi Germany in 1945—the Soviet flag waving triumphantly above Berlin’s battered Reichstag building. Yet behind this enduring image lies controversy, confusion, and political manipulation. Who truly raised the Soviet banner atop the Reichstag? Was it a spontaneous act of heroism or carefully staged Soviet propaganda? Decades later, unraveling the truth reveals surprising layers beneath the mythologized symbol of Soviet triumph.

Who Was Really Responsible For The Reichstag Fire? – Mythbusting Berlin

Various theories have been posited as to who actually set fire to the German parliament in 1933. Was it the opening act in an attempted Communist coup or a calculated false flag operation carried out by elements of the Nazi Party, intended to create the conditions necessary for introducing single-party rule? And what part did the young man from Holland, arrested shirtless inside the building the night of the fire, play in this event?

Who Were The Last Nazis On Trial? – Mythbusting Berlin

More than eighty years after the Holocaust, courtrooms across Germany still echo with testimony from the final chapter of Nazi justice. Centenarian defendants in wheelchairs, their faces hidden behind folders, arrive to answer for crimes committed in their youth. These are not the architects of genocide—those men faced their reckoning at Nuremberg decades ago. These are the guards, the secretaries, the bookkeepers: ordinary people who enabled extraordinary evil. Their trials represent a legal revolution: the

Why Is Berlin The Capital Of Germany? – Mythbusting Berlin

There was little in its humble origins—as a twin trading outpost on a minor European river—to suggest that Berlin was destined for greatness. It sits on the flat expanse of the North European Plain, a landscape once dismissively referred to as the “sandbox of the Holy Roman Empire.” Unlike other world capitals, it lacks breathtaking scenery or a naturally defensible position. It is a city built not on majestic hills or a grand harbour, but