“The sea is blue, but not the blue of water, but of liquid paint (…) Van Gogh has returned the colours to Nature, but who will return them to him?”

Antonin Artaud

In 1706, a Berlin alchemist’s serendipitous discovery unleashed a wave of colour that washed over art and science worldwide.

Of all the colours of the rainbow, blue is undoubtedly one of the most evocative.

It is said to be the colour of the sky – the colour of the ocean – a colour so representative that it has become synonymous with a heightened state of misery.

Humans have been reaching for the elusive hue in myriad ways. The desire to replicate this naturally occurring pigment has led over the past 300,000 years of human history to various potions and compositions – rare and an expression of extreme wealth when used.

To create blue, then, was nowhere near as simple as to be blue – or see it.

In this mythbusting journey, we’ll unravel the history of blue, from ancient Egyptian dyes to the accidental birth of Prussian Blue, and explore how Berlin’s legacy shaped our understanding of ‘God’s favourite colour’.

Along the way, we’ll challenge myths about seeing blue, traverse colonial indigo plantations, climb mountains with a cyanometer, and peer into Van Gogh’s starry sky – all to answer the question: what does Berlin have to do with blue?

–

Blue Before Berlin: Ancient Pigments and Precious Dyes

“…and saw the God of Israel. Under his feet was something like a pavement made of lapis lazuli, as bright blue as the sky.”

Exodus 24:10

Long before Berlin appeared on any map, ancient civilizations were enchanted by blue – even as they struggled to obtain it.

In fact, the very first artificial pigment in human history was blue.

Around 4,500 years ago, Egyptian artisans invented ‘Egyptian blue’, a bright blue crystalline pigment made from sand, copper, and lime. This calcium-copper silicate compound was laboriously produced in kilns at temperatures nearing 900°C, evidence of the Egyptians’ advanced grasp of chemistry.

Egyptian blue (known as hsbd-iryt in Egyptian, literally ‘artificial lapis lazuli’) was used to adorn tomb paintings, statues, and ceramics, signaling prestige and divinity. The Egyptians held the colour in high regard – they even had a word for “blue,” unique among ancient cultures.

By contrast, other early peoples often lumped blues with greens or blacks in their language. Egypt’s mastery of blue pigment gave them not just art, but also a linguistic distinction; as one historian notes, “the Egyptians may have been the only ancients with a word for ‘blue’” – a point we’ll revisit when we discuss whether people saw blue the same way in antiquity.

Sadly, like with the understanding of the hieroglyphics of ancient Egypt, the secret to manufacturing Egyptian Blue was lost sometime after the fall of Rome.

Lapis Lazuli: “Beyond the Sea.”

Meanwhile, nature offered one shimmering blue gem: lapis lazuli, mined in what is now Afghanistan. So scarce it was that medieval and Renaissance Europeans reserved ground lapis – known as ultramarine (Latin for “beyond the sea”) – for only the most sacred subjects in painting.

The Egyptian Book of the Dead recognizes lapis lazuli, carved in the shape of an eye and set in gold, as an amulet of inestimable power. Cleopatra reportedly even wore powdered lapis lazuli as eye shadow.

Pound for pound, ultramarine pigment was once literally worth more than gold. Artists like Michelangelo struggled to afford enough for the skies and robes of their paintings, sometimes leaving works unfinished when they ran out.

In the 1600s, Dutch painter Vermeer spent a fortune on ultramarine, reportedly plunging his family into debt for the rich blues of paintings like Girl with a Pearl Earring. Pulverizing lapis into pigment was painstaking: the rock was ground to powder, mixed with waxes and resins, and kneaded in lye to extract the pure blue particles. The result was an ethereal blue of unparalleled depth – so vivid that European contract law occasionally required patrons to specifically finance ultramarine for an artwork. Less scrupulous painters sometimes cheated by swapping in cheaper blues like azurite or smalt glass, but if caught, their reputations were ruined.

For centuries, ultramarine’s rarity meant blue was a status symbol in art, draping the robes of the Virgin Mary and Christ in its celestial hue.

Not until 1826 did a synthetic ultramarine (invented in France) finally democratize this “blue beyond the sea” – but by then, another blue from Berlin had already taken the world by storm.

Indigo and Woad: Blue Gold of the Ancients.

While painters coveted ultramarine, peoples across the world found blue for cloth in the form of indigo – a dye extracted from indigofera plants.

From India to Africa to the Americas, indigo dyeing has a 5,000-year history and was so valued it earned the nickname “blue gold”.

In India, indigo was being used by the 4th century BC and traded to the Greco-Roman world (the Greek word for indigo, indikon, simply means “from India”). Indigo’s deep blue was tricky to produce: fermenting leaves in vats to precipitate the dye, then oxidizing it to create a water-insoluble pigment that could bond to fibers.

Despite the complexity, many cultures considered indigo-dyed textiles a sign of wealth or mystique – from the ceremonial blue facepaint of certain West African communities to the blue burial cloths of Egyptian mummies.

In Europe, native woad (a related plant) yielded a blue dye, but it was paler and less colourfast. When high-quality indigo began arriving via trade in the Middle Ages, it quickly eclipsed woad – so much so that some woad-growing regions panicked. In 16th-century Germany and France, indigo imports were banned as an “evil” threat to the local woad industry. (The bans didn’t last – demand for indigo was unstoppable.)

By the 1700s and 1800s, indigo had become a cornerstone of colonial trade, grown on plantations in India, the Caribbean, and the American South under oppressive conditions. Indeed, during the American Revolution, indigo made up a full one quarter of the South Carolina colony’s exports by value, second only to rice. No wonder indigo was called “blue gold” – it was literally funding empires.

Centuries before Berlin even entered the picture, blue pigments and dyes already had a rich history – from Egyptian blue on pharaohs’ tombs, to lapis on Renaissance canvases, to indigo on fabrics across the globe. Blue was precious, elusive, and deeply symbolic. But it was also limited: difficult to obtain, expensive to use, and often chemically imperfect (azurite tended to green over time; indigo-dyed cloth could fade).

A truly affordable, stable blue pigment that anyone could use remained the holy grail.

That is, until an accidental discovery in a Berlin laboratory changed the colour game forever.

–

The Berlin Blue Breakthrough: Prussian Blue’s Accidental Invention

“Nothing is perhaps more peculiar than the process by which one obtains Prussian blue… And if chance hadn’t taken a hand, you‘d have to admit that a profound theory would be necessary to invent it.”

French chemist Jean Hellot

In the early 1700s, Berlin was a hive of alchemists and early chemists, drawn by the Prussian king’s patronage of the sciences.

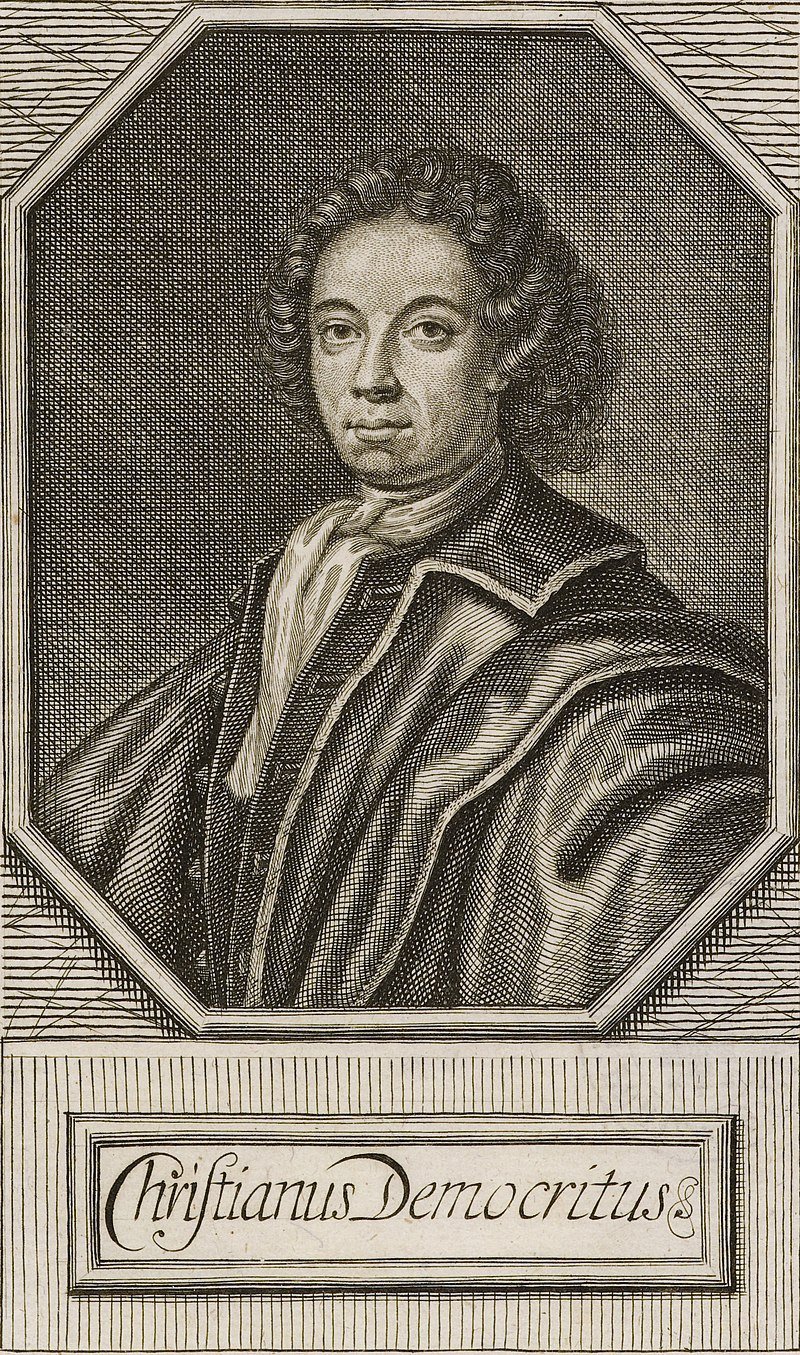

Among those seeking fortunes was Johann Jacob Diesbach, a pigment-maker from Switzerland, and Johann Conrad Dippel, an alchemist infamous for his experiments with animal materials (and later, rumored inspiration for Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein).

In 1706, in Dippel’s laboratory in Berlin, Diesbach was trying to create a batch of red pigment – a Florentine lake derived from cochineal insects. Finding himself low on the potash (potassium carbonate) needed for his recipe, Diesbach borrowed some from Dippel’s stores. Unbeknownst to him, Dippel’s potash was contaminated with “animal oil” from one of the alchemist’s gruesome concoctions – a substance derived from distilled blood and bones, rich in iron. The next morning, Diesbach was greeted not by the rich crimson he expected, but by a substance of an entirely different colour. The cochineal mixture, interacting with Dippel’s potash impurities, had produced a deep blue precipitate.

Diesbach was astonished.

Once the initial shock subsided, he and Dippel began investigating this unintended blue. They soon discovered the formula to reliably reproduce it: animal oil (with its blood’s iron) and potash had reacted with the iron sulfate in the cochineal process to form ferrocyanide, which then yielded an iron-based pigment – ferric ferrocyanide. In simpler terms, their mistake had yielded a new chemical compound: a stable blue pigment that the world had never seen. Crucially, this blue was colourfast (resistant to fading) and non-toxic.

Unlike indigo dye which could wash out, or expensive ultramarine only the rich could afford, this accidental Berlin blue was inexpensive to make from common chemicals – an alchemical misfire turned into a goldmine of colour.

Thus ‘Prussian Blue’ was born.

It didn’t take long for word – and samples – of Diesbach’s blue to spread among the scientific and artistic community.

By 1709, the new pigment was being referred to as Preußisch Blau (“Prussian Blue”) and sometimes Berlinisch Blau (“Berlin Blue”). The names acknowledged its origin in the Kingdom of Prussia and the city of Berlin.

Initially, Diesbach and Dippel kept the manufacturing process a closely guarded secret – with good reason. This was the first modern synthetic pigment – not ground from a mineral or extracted from a plant, but cooked up in a lab – and its inventors stood to profit immensely as sole suppliers. For a few years, they did. Prussian Blue proved cheap to produce and of superb quality, and orders poured in from painters and dye manufacturers across Europe.

However, drama soon followed.

Dippel, quarrelsome by nature, fell into political trouble (involving an anti-Swedish pamphlet) and had to flee Berlin in 1707, leaving Diesbach on his own. Diesbach partnered with a local businessman, Johann Leonhard Frisch, to commercialize the pigment. Later, a dispute arose over who deserved credit for the invention – Diesbach the chemist or Frisch the promoter – showing that even in the 1710s, intellectual property rights could get heated.

Regardless of who got the credit (history ultimately favors Diesbach), Prussian Blue soon exploded in popularity.

By 1724, the secret of its recipe had leaked out (reportedly published in England), breaking the monopoly and allowing others to produce the pigment. From that point on, Prussian Blue became a democratic blue – available to any artist, printer, or fabric dyer, an affordable substitute for the costly blue materials of old.

The impact of Prussian Blue in Europe can’t be overstated.

Historian Hugh Davies notes that “the immense value of the substance was immediately clear” – a stable blue that didn’t fade was literally “more valuable than gold” to early 18th-century artists, given the fortune they otherwise spent on ultramarine.

Before this, the palette of a typical Baroque painter had a conspicuous gap where a brilliant blue should be.

Now suddenly, anyone could paint a bright sky or a vivid blue coat without bankrupting their patron.

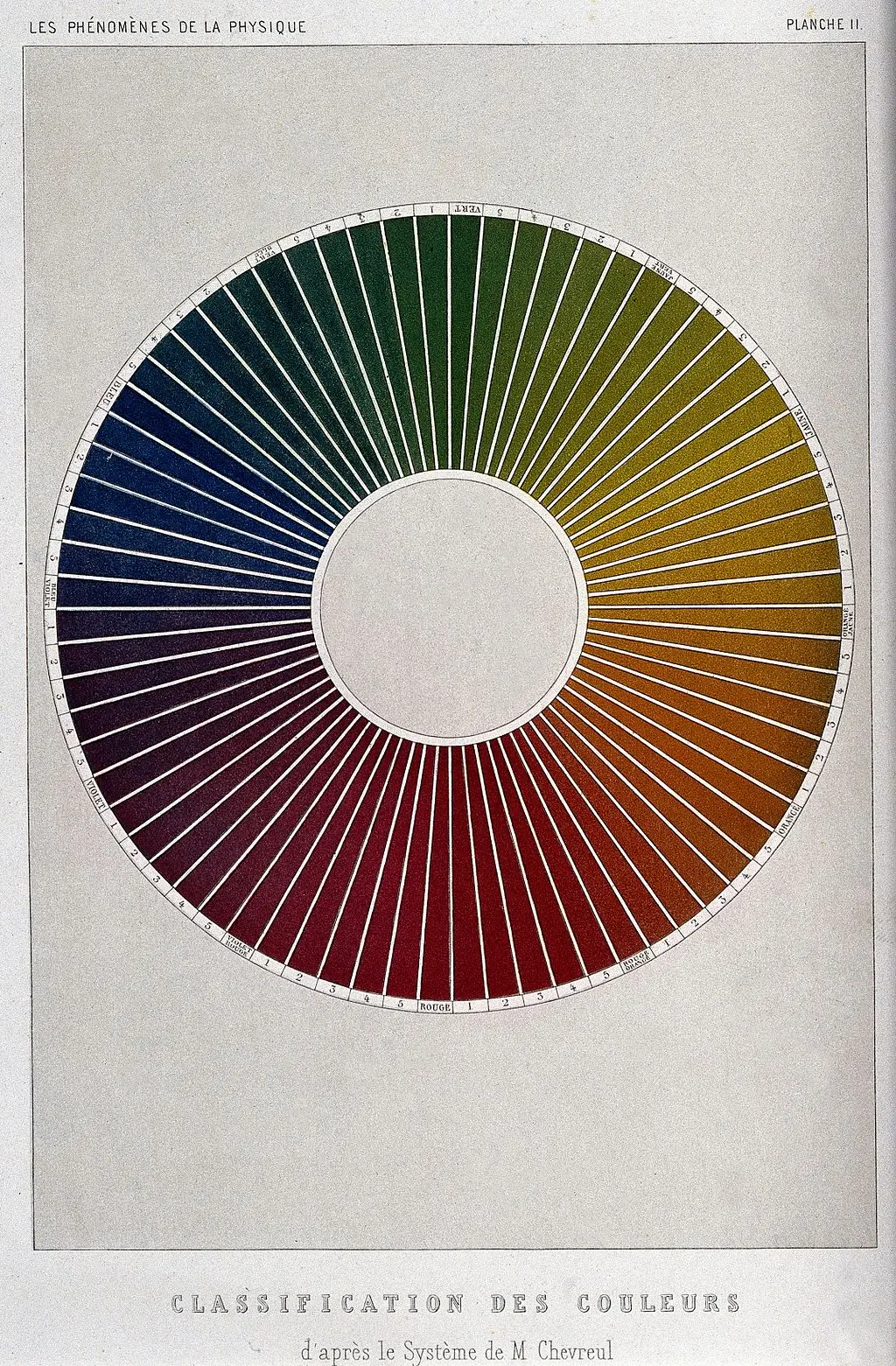

The new pigment spread rapidly: by the 1720s it featured in the palettes of painters in France and England; by mid-century it had largely supplanted smalt (a duller ground glass pigment) and azurite in most artistic uses. Prussian Blue’s advantages were evident: unlike organic dyes it didn’t require mordants or binders that could dull its hue; unlike ground minerals it had a high tinting strength – a little went a long way in oil paint or watercolour. And its deep, greenish-blue tone was unique – darker and moodier than cobalt blue (which came later in 1802), with a subtle green undertone that gave it complexity.

As one later commentator described it, Prussian Blue is “darker than cobalt and moodier even than indigo (and with enough green that it sometimes reads as a dark teal)”.

It even entered fashion and decor.

In 1709, Prussia’s King Friedrich Wilhelm I, impressed by the new pigment, ordered his military uniforms to adopt a deep blue coat – the birth of Prussian military blue uniforms. (This pragmatic king reputedly liked that the dye was cheap and colourfast, so his soldiers’ coats wouldn’t fade – cost-saving even in colour choice!).

Prussian Blue ink began to be used in official documents and postage stamps; by 1840, Britain’s famous Penny Blue stamp owed its hue to Prussian Blue pigment.

The pigment even found scientific uses: it became the basis of one of the earliest photographic processes, blueprints, invented by astronomer John Herschel in 1842. Herschel found that UV-exposed iron salts on paper would turn Prussian Blue when developed in potassium ferrocyanide, yielding a white-on-blue copy of an engineering drawing – coining the term “blueprint” in the process.

From fine art to the blue paper plans of the industrial age, Berlin’s accidental colour was everywhere.

Berlin had not invented the idea of blue – but with Prussian Blue, it invented the era of blue as a common, everyday colour.

No longer the privilege of pharaohs or Renaissance masters, blue was now within reach of every painter and printer.

And just as Berlin’s new blue reached the wider world, the wider world’s appetite for blue would reach Berlin in unexpected ways – from the woodblock prints of distant Japan to the starry skies of a Dutch Post-Impressionist.

–

The Pigment that Conquered the World: Prussian Blue’s Global Journey

“The deeper the blue becomes, the more strongly it calls man towards the infinite, awakening in him a desire for the pure and, finally, for the supernatural.”

Wassily Kandinsky

In the 18th and 19th centuries, as global trade expanded, Prussian Blue became one of Europe’s hottest exports – including to places that had long traditions of their own blue.

Nowhere was the encounter more transformative than in Japan.

During the late Edo period, Japan began to import Prussian Blue pigment (likely via Dutch traders), calling it bero ai (a corruption of “Berlin indigo”).

Japanese ukiyo-e printmakers, who had previously relied on subdued indigo or dayflower dyes for blues, were astonished by the new pigment’s intensity. By the 1820s, leading artists like Katsushika Hokusai embraced Prussian Blue to create prints with unprecedented vibrancy.

Hokusai’s most famous work, “The Great Wave off Kanagawa” (1831), showcases this boldly. The towering wave in that image is rendered in rich, saturated blues that simply could not have been achieved with traditional Japanese dyes.

The frothing curves of Hokusai’s wave are a study in Prussian Blue’s range: from the deep shadowy navy of the wave’s underside to the bright cerulean foam cresting at the top. It’s the only prominent colour in the print – drawing the eye to the dramatic contrast of sea and sky.

Hokusai was so enamored of the pigment that he produced an entire series, Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji, featuring the Prussian Blue extensively.

Japanese printmakers found that this imported colour was also durable: unlike some vegetal blues that could discolour, the new pigment stayed true. Little did they know they were using a colour invented in Berlin only a century earlier, via a chemical process completely alien to traditional Japanese dye-making.

The flow of Prussian Blue didn’t stop in Japan.

Japanese art itself, coloured with this “Berlin blue,” soon traveled to Europe and fascinated Western artists in the late 19th century.

The trend of Japonisme swept France and beyond, as artists like Claude Monet, James Whistler, and Vincent van Gogh avidly collected Japanese woodblock prints.

They marveled at the expressive use of bold flat colour – especially the deep blues. Unaware of the pigment’s European origin, some Impressionists even dubbed the shade “Hiroshige blue” (after the ukiyo-e master Utagawa Hiroshige) when they saw it in Japanese prints.

In a twist of colour history, Europeans assumed this striking blue was a novel Japanese invention, not realizing it was the same Prussian Blue their own factories produced. As one art historian wryly noted, it was later understood that this “quintessentially Japanese colour was itself an ‘old’ European invention”.

The cross-cultural pollination of Prussian Blue led to some of the 19th century’s most famous art. Vincent van Gogh, for instance, was an avid admirer of Japanese prints and was directly influenced by their use of colour.

In 1888 he wrote, “All my work is based to some extent on Japanese art”.

Van Gogh’s Starry Night (1889), with its whirling blue sky, is often cited as an example of this influence. Some art scholars believe Starry Night was in part a response to Hokusai’s dramatic depictions of nature – essentially Van Gogh’s attempt to paint a “Japanese” sky with Western materials. While Van Gogh’s vivid cobalt blues and ultramarines dominate the sky of Starry Night, Prussian Blue quietly plays a role too.

Analysis of the painting reveals that Van Gogh mixed Prussian Blue into the greens of the cypress tree in the foreground.

By blending Prussian Blue with yellow, he created the dark teal-green for the tree, a technique he may have picked up from Hiroshige’s landscape prints where similar mixtures appeared.

In fact, Van Gogh and his contemporaries often kept Prussian Blue on their palettes; its deep tint was useful for night scenes and shadows.

Beyond Van Gogh, virtually every major European artist of the 18th–19th centuries made use of Prussian Blue.

- Goya mixed it into the backgrounds of his dark romantic scenes.

- Turner experimented with it in his seascapes (though he complained it could overpower other colours if not used sparingly).

- The French Impressionists, with their love of painting en plein air, relied on Prussian Blue for capturing the deep shadows of twilight or a stormy sky.

- In the United States, naturalist painter John James Audubon used Prussian Blue to portray the iridescent blues of birds in The Birds of America

- Winslow Homer also used it for the tropical seas in his Caribbean watercolours

By the late 1800s, Prussian Blue was so ubiquitous that Henry David Thoreau (somewhat tongue-in-cheek) grumbled about its name. In an essay, Thoreau mused why Americans should refer to colours by “obscure foreign localities” like Prussian Blue or “articles of commerce” like sienna or umber – suggesting Americans name the colours of their world after local nature instead (he proposed things like “hickory” for yellow).

Thoreau’s nationalist colour nomenclature never caught on.

Prussian Blue kept its name globally, a reminder of its Berlin origins even as it became the world’s blue.

From a Berlin lab accident, Prussian Blue went on to become a world traveler: changing fine art in Europe, inspiring new directions in Japanese art, colouring postage stamps and military uniforms, and even seeping into common language (the “Blueprint” plans of architects, the “blueprints for murder” in later dark chapters involving this pigment’s chemistry).

In the next sections, we’ll step back from pigments and paintings to ask a deeper question: How do humans perceive blue in the first place? And why did it take so long for us to give “blue” a name?

The answer we’ll find links language, science, and a bit of philosophy – and it will shed light on why some might think blue was a recent “invention.”

–

Seeing Blue: The Science and Language of Colour Perception

“It must be remembered that when colours such as yellow and blue mix in our eyes, their pigment can settle on our thoughts.”

Virginia Woolf

One of the most intriguing myths about the colour blue is that humans ‘didn’t see’ blue in ancient times because they had no word for it.

This idea gained traction from the observation that many ancient texts – famously Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey – describe the sea as “wine-dark” and never explicitly call the sky “blue.”

Indeed, 19th-century scholars like William Gladstone (better known as a British Prime Minister, but also a Homeric researcher) systematically counted colour references in Homer and found some puzzling results.

In Homer’s epic poems, black is mentioned nearly 200 times and white about 100, but other colours are scarce; red is fewer than 15 times, yellow and green under 10, and blue not at all.

To the Greek poets, honey was described as green, iron as violet – a very different colour vocabulary than ours.

Following Gladstone, a philologist named Lazarus Geiger compared ancient writings from around the world – Icelandic sagas, the Quran, Vedic hymns, the Bible – and noted a consistent pattern: blue was rarely mentioned, if at all.

It seemed that before a certain point in history, no culture had a distinct concept for blue. Geiger discovered a curious timeline: almost every language develops words for colours in the same sequence.

First come words for black (or dark) and white (or light), then a word for red, then yellow or green, and only later, after green, does a word for blue appear. In fact, as Geiger and later researchers (including anthropologists Brent Berlin and Paul Kay in the 1960s) found, blue consistently tends to be the last major colour word to emerge in a language.

The only exception among ancient civilizations, tellingly, was Egypt: Egyptian language had a word for blue early on – and notably, Egypt was the only ancient culture that had mastered a blue pigment (Egyptian blue) and blue dyes.

As one modern summary puts it, “The only ancient culture to develop a word for blue was the Egyptians — and as it happens, they were also the only culture that had a way to produce a blue dye.”

In other words, necessity (or at least availability) is the mother of linguistics: have a blue dye, and you’ll name a colour “blue.” But does lack of a word mean lack of perception? Did Greeks literally not see blue the way we do? That’s a trickier question.

The human eye’s physiology hasn’t changed in the last few thousand years – our ancestors were not colourblind.

Most scientists believe ancient peoples could perceive blue, but perhaps paid it less attention or categorized it differently. Cognitive linguistics suggests that if you have no word for a colour, you may be slower to recognize it or treat it as important.

A famous experiment in modern times illustrates this: researchers showed members of the Himba tribe of Namibia (whose language has no separate word for blue; it uses one term for blue-green) a circle of 12 squares: 11 were green, and 1 was a clear blue.

To English speakers, the blue square pops out immediately. But the Himba participants struggled to identify which square was different – some said none were.

Without a linguistic label for blue, the difference was less salient to them.

Conversely, the Himba have more distinct words for varieties of green than English does.

When shown 12 green squares where one was a slightly different shade, they detected the odd one much faster than English speakers, who often couldn’t see it at all.

Language, it seems, can shape what we notice.

In ancient texts, descriptions like Homer’s “wine-dark sea” might reflect a world where colour was described in terms of texture, function, or emotional resonance rather than strict hue. The sea could be “wine-dark” to evoke its deep, stormy quality; honey “green” to suggest its fresh, liquid shine. Perhaps early cultures simply didn’t isolate the notion of “blueness.”

Notably, the sky itself was often not described as blue in many languages; without pollution, the sky can appear very pale, or people might have seen it as the absence of colour, or taken it for granted. It wasn’t until humans had man-made blue pigments and traded textiles that “blue” became an everyday concept that needed a name.

Modern linguist Guy Deutscher explored this idea by a playful experiment on his young daughter. He deliberately never told her the sky was “blue” to see when (or if) she would identify that colour on her own.

One day, looking up, she amusingly described the sky as white – she hadn’t yet learned to see that particular colour as distinct.

Only after prompting did she acknowledge it as blue, demonstrating how children must learn to “see” colours through language and cultural context. So, while it’s not true that ancient people literally couldn’t see blue, it is true they often didn’t single it out. Blue was there (flowers, birds, lapis jewelry, the sky) but it was hiding in plain sight, unnamed and thus in a sense unnoticed.

Why is blue the last colour to gain a name?

Part of the answer lies in nature.

Pure blues are exceedingly rare in the natural world.

Unlike reds (blood, clay, fire) or greens (plants everywhere) or yellows (sun, wheat), blue pigments are hard to come by.

No blue fruit or vegetable was common in the ancestral human diet; blue animals are few (a robin’s egg or a butterfly’s wing have structural blue, not pigment).

The most prominent blue thing in daily life is the sky – but you can’t touch the sky.

Some ancient philosophers even argued the sky wasn’t really a colour, but just light.

Thus early societies may not have considered “sky-blue” a colour category on its own. It took technology to bring blue into the foreground – grinding lapis lazuli, inventing Egyptian blue glaze, extracting indigo dye.

With each innovation, blue became more visible and economically significant, demanding a name. The Egyptians, having painted tombs and dyed fabrics blue, coined terms for it (ancient Egyptian had khesbedj for the deep blue of lapis, for example).

Other societies, lacking these materials, got by without naming that slice of the spectrum. Interestingly, once a culture does name blue, it tends to differentiate many blues (light, dark, etc.) rapidly.

In modern English we have baby-blue, navy, teal, cyan, azure – an explosion of blues that would bewilder Homer.

In sum, Berlin did not “invent” the colour blue in a literal sense – our ability to see blue is human and physiological.

But Berlin’s Prussian Blue arrived at a pivotal moment in history when the world was finally ready to see blue in all its glory.

As we’ve seen, by 1700 European culture had embraced blue (the Virgin Mary’s robes, the flags and heraldry of nations), yet supply was limited.

Prussian Blue was the catalyst that let art and industry drench themselves in blue.

And ironically, just a few decades after Prussian Blue’s invention, scientists also began earnest investigations into why the sky is blue – another mystery about the colour that had long puzzled thinkers.

–

Measuring the Sky: Humboldt and the Cyanometer

“The sky is blue because you want to know why the sky is blue.”

Jack Kerouac

While artists were celebrating Prussian Blue on canvas, natural philosophers were turning their eyes upward, wondering about the immense blue overhead.

Why is the sky blue, and just how blue is it?

Enter one of the more poetic scientific instruments ever invented: the cyanometer – a device for measuring the blueness of the sky.

In 1789, Swiss physicist Horace-Bénédict de Saussure crafted a circular tool with 52 sections of paper, each dyed a slightly different shade of blue, from almost white to near-black navy. By comparing the colour of the open sky to the closest match on this palette, Saussure’s cyanometer (“blue-measurer”) provided a numeric index of blueness. At the summit of Mont Blanc, Europe’s highest peak, Saussure determined the sky to be a deep “blue 39°” on his scale.

The concept was that a sky free of haze and moisture would be a darker blue; thus, the cyanometer could indirectly measure atmospheric clarity or humidity.

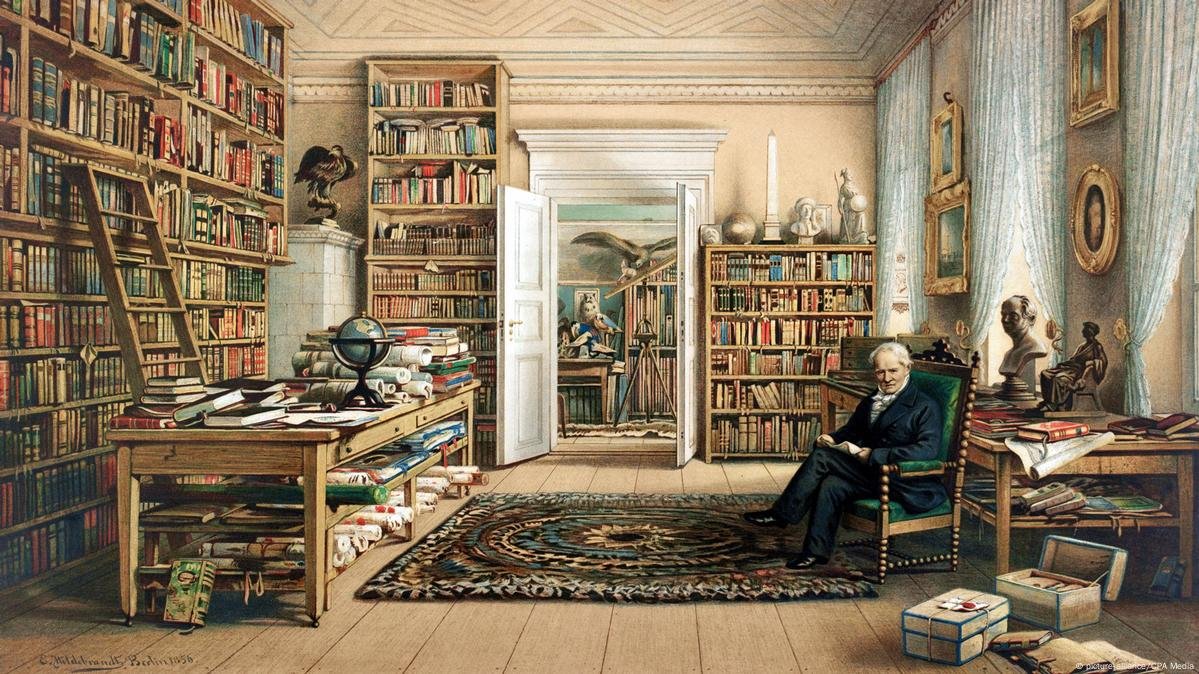

This peculiar gadget might have remained a scientific footnote if not for Alexander von Humboldt, the great Prussian explorer and polymath – who had deep roots in Berlin’s scientific community. Humboldt was a true child of the Enlightenment and a bit of a romantic when it came to nature. He seized upon the cyanometer as a means to quantify one of nature’s subtlest beauties.

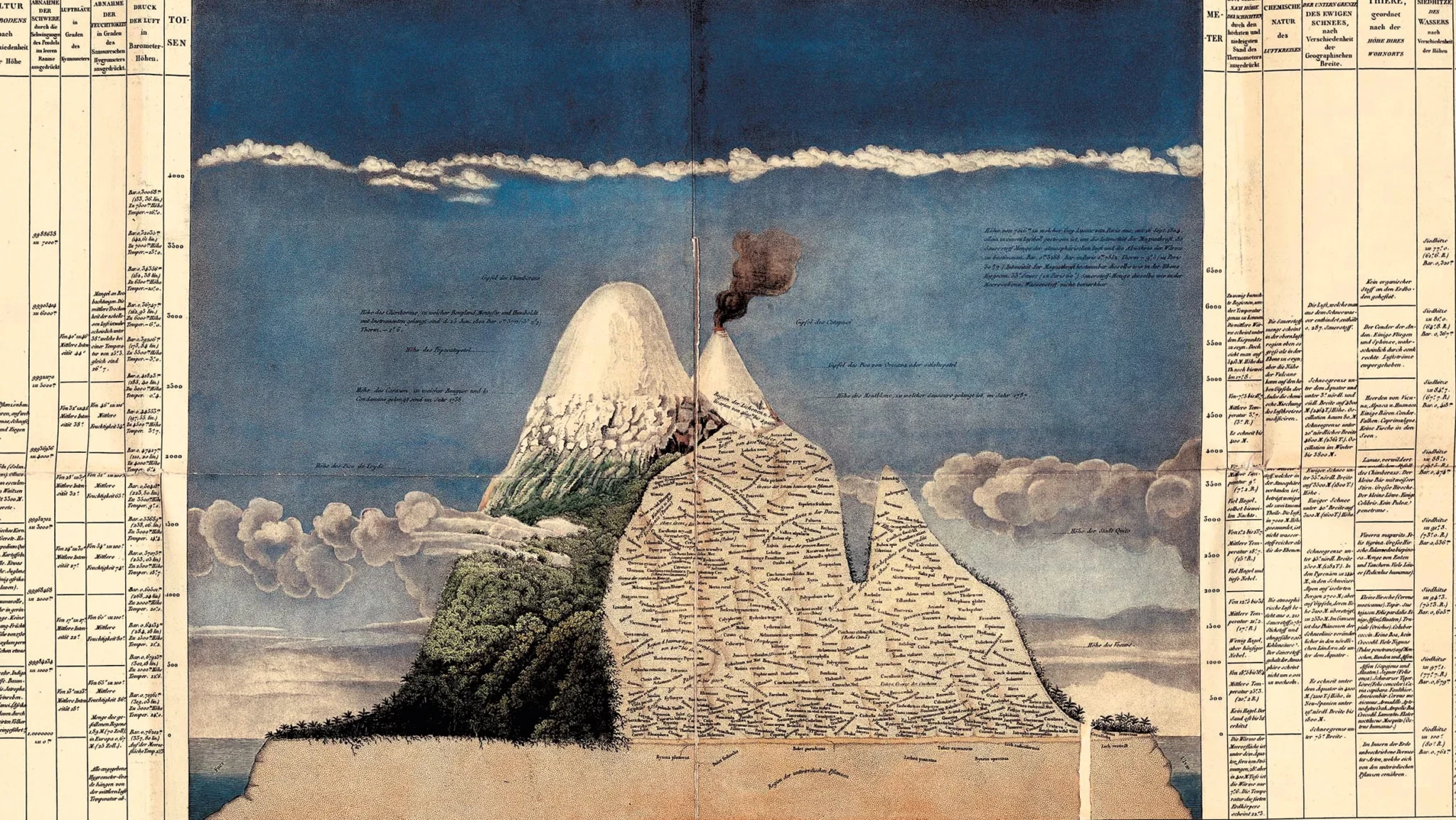

In 1802, during his famous expedition across the Americas, Humboldt carried a cyanometer with him from the tropics to the high Andes.

Climbing the Andean volcano Chimborazo (then believed to be the tallest mountain in the world), Humboldt reached altitudes over 5,000 meters and held up Saussure’s blue wheel to the zenith. The reading: a sky of “blue 46°”, even deeper than Mont Blanc’s, setting a new record at the time for the darkest blue sky measured. Humboldt’s meticulous journals note these observations, making him one of the first scientists to gather data on sky colour in different parts of the world.

So what did the cyanometer ultimately teach us? In Humboldt’s time, its readings hinted at what might cause the sky’s colour. Saussure suspected the intensity of blue was related to “vapors” in the air.

He was partially right – we now know that a dry, unpolluted sky (like at high altitude) is a deeper blue, whereas moisture and particles make the sky paler.

But the full explanation had to wait for the work of 19th-century physicists like John Tyndall and Lord Rayleigh, who in the 1860s figured out that scattering of sunlight by air molecules causes the blue hue. Tiny molecules preferentially scatter shorter blue wavelengths of sunlight in all directions, colouring the sky.

When this was discovered, the cyanometer became scientifically obsolete.

It turned out the device, while charming, wasn’t very precise for rigorous science.

By the late 1800s, it was relegated to museums, seen as an artifact of a bygone era of natural philosophy. Yet, symbolically, the cyanometer is a fitting piece of the blue story. It straddles art and science – essentially a watercolour palette turned scientific instrument.

And it ties back to Berlin through Humboldt.

After his travels, Alexander von Humboldt settled back in his hometown of Berlin, where he became a central figure in the city’s scientific institutions (he was a founder of the University of Berlin).

In his famous book Cosmos, written in Berlin in the 1840s, Humboldt rhapsodised about the colour of the sky and the interconnectedness of nature’s patterns.

One can imagine him showing off his cyanometer to guests in a Berlin salon, marveling at how something as ineffable as “blueness” could be measured and recorded.

The cyanometer also underscores how Berlin (and Prussia) was plugged into the global network of scientific ideas.

Saussure’s invention in Geneva found one of its greatest champions in a Prussian scientist who carried it to South America.

In a way, Berlin helped bring the measure of blue to the world, just as it had brought a pigment of blue to the world.

–

The Colour Of Suffering: Indigo Away

“More than any other plant, indigo impoverishes the soul”

Alexander von Humboldt

No story of blue is complete without examining the darker side of our obsession with this colour – the human and environmental toll of getting blue out of nature and into our lives.

We’ve already touched on how indigo dye was “blue gold” in the colonial era, but let’s dig deeper into that legacy and how Berlin’s Prussian Blue and later innovations affected it. The Indigo Empire.

By the 18th century, Europe’s appetite for blue-dyed textiles (uniforms, fashion, household goods) had grown insatiable.

The primary source: natural indigo from colonies in India and beyond.

The British, French, and Spanish colonial powers established vast indigo plantations manned by slave labor or oppressed local farmers. Conditions were often brutal. In the French West Indies and American South, enslaved Africans were forced to cultivate and process indigo, enduring toxic fumes from fermentation vats and grueling labor.

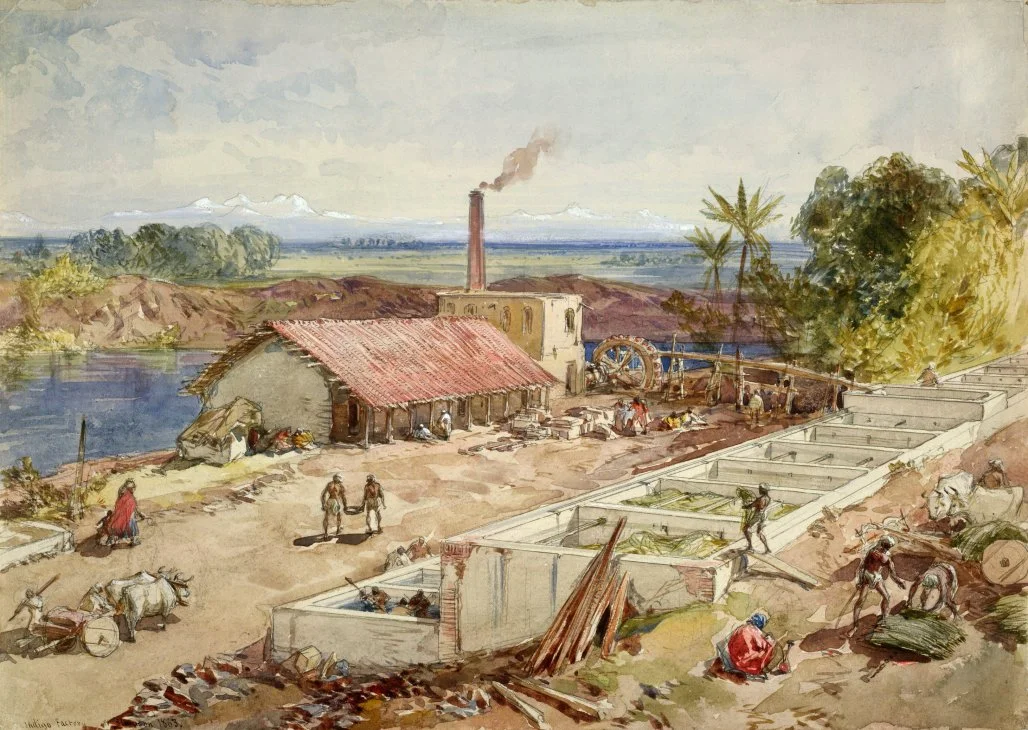

In British-ruled India, especially Bengal, peasants were coerced by plantation owners (the planters) into growing indigo instead of food, for meager pay.

The situation grew so dire that it sparked what is often considered the first non-violent mass protest in Indian history – the Indigo Revolt of 1859, where tens of thousands of farmers refused to sow indigo in protest of their exploitation. Earlier, as indigo demand soared, unscrupulous practices abounded: in Japan, indigo was so valuable that sharing its production secrets was punishable by death. In West Africa, centuries-old indigo dye traditions were co-opted and commercialized under colonial rule.

The competition for indigo markets was literally cutthroat – European indigo planters and traders fought for dominance, prompting one 19th-century commentator to label indigo “the devil’s dye” for all the misery and “brutal and bloody” deeds associated with it.

The invention of Prussian Blue in 1706 slightly alleviated reliance on indigo for painters and inks, but for fabrics indigo was still king.

It wasn’t until the late 19th century that chemistry struck another blow: German chemist Adolf von Baeyer (ironically, a product of Berlin’s own scientific milieu – he studied under Robert Bunsen and later taught in Berlin) devoted years to unraveling indigo’s formula. In 1878, Baeyer succeeded in synthesizing indigo in the lab. By 1897, the German chemical company BASF had industrialized the process, producing synthetic indigo at scale.

The effects were dramatic and swift.

In 1897, an estimated 19,000 tons of natural indigo were still being produced globally; by 1914, with synthetic indigo ascendant, natural indigo production plummeted to just 1,000 tons.

An economic pillar of colonial agriculture collapsed virtually overnight.

Indian indigo plantations shut down as the cheaper factory-made dye from Germany flooded the market.

A dye that for centuries had underwritten colonial wealth and oppression was supplanted by one of the very nations that had once imported it.

In a sense, Berlin (and broader Germany) played an indirect role here too: the German advances in organic chemistry – an area in which Berlin’s universities excelled – led to synthetic dyes that liberated the colour blue from the soil. One could say the invention of synthetic Prussian Blue in 1706 was the first shot, and synthetic indigo in the 1890s the final coup de grâce, in ending the era of natural blue dyes.

This was good news for consumers (cheaper blue clothes) and arguably for workers (no more forced indigo farming on the same scale), but it had other costs.

The new synthetic dye industry created its own environmental challenges. Early dye factories released hazardous chemicals into rivers. By the 20th century, the textile dyeing industry (with blue dyes like indigo for denim being major contributors) became a significant polluter. According to modern analyses, around 17–20% of industrial water pollution comes from textile dyeing and treatment. Indigo dye – whether plant-based or synthetic – if not managed properly can turn waterways dark blue, harming aquatic life. Even today, places that mass-produce denim (which uses indigo dye) have struggled with dye pollution turning rivers unnatural colours.

Thus, the story of blue has come full circle in a way: we no longer scour deserts for rare lapis or force farmers to grow indigo under the whip, but we now grapple with how our synthetic blues impact the planet’s waterways.

Interestingly, the push for more sustainable dyes has seen a modest return to natural indigo farming in some places (with better labor practices), and research into bacteria-based indigo production or new techniques that avoid the toxic waste.

But these are challenges of chemistry and industry that continue today.

Berlin’s role in the environmental side of blue is largely through its contributions to chemical education and industry in the 19th century – which trained people like Baeyer. By the early 1900s, Germany (with Berlin as an intellectual capital) dominated the global dye market, and indigo was a jewel in that crown.

One can even find a poignant connection: in 1905, Adolf von Baeyer was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry, and in his Nobel lecture he reminisced about indigo, noting how this dye had “fascinated [him] since youth” and how its synthesis, though solving a grand scientific puzzle, led to the decline of an agriculture that had lasted centuries.

The environmental impact of blue goes beyond indigo.

Consider Prussian Blue itself: it contains cyanide in complex form, and when acidified or burned, can release hydrogen cyanide gas.

In one grim chapter, the walls of certain World War II gas chambers were stained with “Prussian Blue” residues – a dark irony that the pigment formed as a by-product of cyanide used in the Holocaust.

While the colour itself wasn’t to blame, its chemistry intersected with tragedy.

Prussian Blue also found a positive use in modern medicine: it is used as an antidote for certain heavy metal poisonings (like radioactive cesium and thallium), administered in capsules to bind the toxins in the gut.

A colour that once tainted artists’ hands now saves lives by cleansing bodies of radiation – a reminder of the strange twists in the tale of any technology.

Through all these twists, Berlin pops up repeatedly: as the birthplace of Prussian Blue pigment; as a nexus of 19th-century chemical innovation that gave us synthetic dyes; and as the home of scientists like Humboldt who quantified nature’s blueness. It seems the city has an enduring link with this colour, from art to science to industry.

**

Conclusion

So, was the colour blue invented in Berlin?

Naturally, no – blue has existed in nature’s palette and humanity’s story since time immemorial.

The ancient sky and sea were as blue in Homer’s day as now (even if he called the sea dark wine). Egyptians were making blue pigments 4,500 years ago; traders carried indigo dye across continents long before the Margraviate of Brandenburg (let alone Prussia) even existed.

But the myth of Berlin inventing blue contains a kernel of truth: Berlin was the cradle of a blue revolution.

In the early 18th century, Johann Diesbach’s Berlin laboratory gave birth to Prussian Blue, the first modern synthetic colourant, shattering the tyranny of expensive or fugitive blues and democratizing the colour for all.

That singular event in 1706 set off a chain reaction. Prussian Blue became a world traveler – from the palette of Katsushika Hokusai in Japan to the paintbox of Van Gogh in France – a vivid example of Berlin’s global cultural impact.

Berlin’s scientists, like Humboldt, further entwined the city’s name with blue through their quest to understand nature’s blueness, even carrying Berlin-made instruments to the peaks of the Andes to measure the sky.

And Berlin’s chemical pioneers helped transition the world from natural dyes to synthetics, upending colonial economies built on “blue gold” and ushering in the age of industrial colour – with all its benefits and downsides.

In unmasking the myth, we find that Berlin’s role was not to conjure blue into existence, but to profoundly influence the accessibility, understanding, and significance of blue in the human experience.

Prussian Blue gave artists a new storytelling tool – think of all the profound emotions conveyed by a colour that finally anyone could afford to put on canvas, from the melancholy of Picasso’s Blue Period (made possible by cheap Prussian Blue paint) to the nationalism of Prussian military uniforms.

The cyanometer and scientific endeavors in Berlin gave people a way to talk about the sky’s blueness in quantitative terms, bridging subjective beauty and objective measurement.

And the late 19th-century breakthroughs in Berlin’s sphere of influence freed the colour blue from the caprices of agriculture and empire, albeit introducing new environmental questions that we grapple with to this day.

Ultimately, Berlin’s relationship with blue is a microcosm of the Enlightenment and modernity: a place where art, science, and industry met to challenge old limits.

Blue was never invented in a single moment – it was slowly discovered, synthesized, named, and appreciated over millennia.

But if we were to pick one locale that did the most to shape our modern perception of blue, Berlin in the 1700s–1800s must rank high.

It turned blue from a luxury into a common language of culture.

It helped turn a mysterious colour of gods and kings into a scientific wavelength we can measure with instruments and describe in any number of Pantone shades.

So the next time you squeeze ultramarine toothpaste or admire a blueprint or gaze at a Prussian blue evening sky, give a nod to Berlin – the city that didn’t invent blue, but undoubtedly painted a chapter in its story.

***

If you’ve enjoyed reading this article, consider booking one of our private guided tours of Berlin.

HISTORICAL ARTICLES

Mythbusting Berlin

Are There Any Nazi Statues Left In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

Visitors to Berlin often arrive expecting to find the physical remnants of the tyranny of the 20th century still standing – statues of dictators, triumphal arches, or bronze idols. Instead, they often find none. The stone symbols and statues of the Third Reich are still gazing down on them, however, hiding in plain sight. But why are there no statues of Hitler? Did the Allies destroy them all in 1945, or is the truth stranger

Could The Western Allies Have Captured Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

To contemplate a Western Allied capture of Berlin in 1945 is to challenge the established endgame of the Second World War. What was the true military and logistical feasibility of a Western Allied assault on the Nazi capital? What factors truly sealed Berlin’s fate, and what might have changed had the Allies pushed eastward?

Answering these questions means delving into the complex interplay of logistics, political maneuvering, and the competing visions for a post-war world

Did Any Of The Rothschild Dynasty Die In The Holocaust? – Mythbusting Berlin

The Rothschild name is synonymous with immense wealth, influence, and persistent conspiracy theories—especially during the era of Nazi Germany. Often targeted by antisemitic propaganda, the family’s survival during World War II has sparked myths about their supposed immunity from Nazi persecution. But did any Rothschild family member actually perish in the Holocaust? This article explores that compelling question, unraveling historical misconceptions and revealing the reality behind one of Europe’s most famous dynasties.

Did Frederick The Great Introduce The Potato To Germany? – Mythbusting Berlin

One of the more bizarre claims to fame attributed to the first King of Prussia is that the man who would go down in history known as Frederick the Great introduced the potato to Germany during his reign back in the 1700s. This starchy root vegetable has undoubtedly become a staple part of German cuisine – an essential addition to any plate of Schnitzel, Schweinshaxn, and Königsberger Klopse – however, whether Frederick the Great is

Did Hitler Escape To Argentina In 1945? – Mythbusting Berlin

Although Nazi leader, Adolf Hitler, certainly remains an inescapable figure, could there be any truth to the story of his escape to Argentina in 1945? That the most wanted man on earth could simply vanish, to spend the rest of his life peacefully in South American obscurity captivates imaginations. Yet, despite numerous investigations, this tale persists primarily as myth—fueled by speculation, hearsay, and conspiracy theories.

Did Hugo Boss Design The Nazi Uniforms? – Mythbusting Berlin

The idea that Hugo Boss – the man whose name now adorns expensive suits and fragrances – was the creative genius behind the Nazi uniforms suggests a terrifying collision of haute couture and holocaust – a marriage of high style and high crimes. The image is striking: a German tailor sketching the ultimate villain’s costume. But history, as usual, is far messier, more bureaucratic, and more banal than the internet memes suggest. To understand who

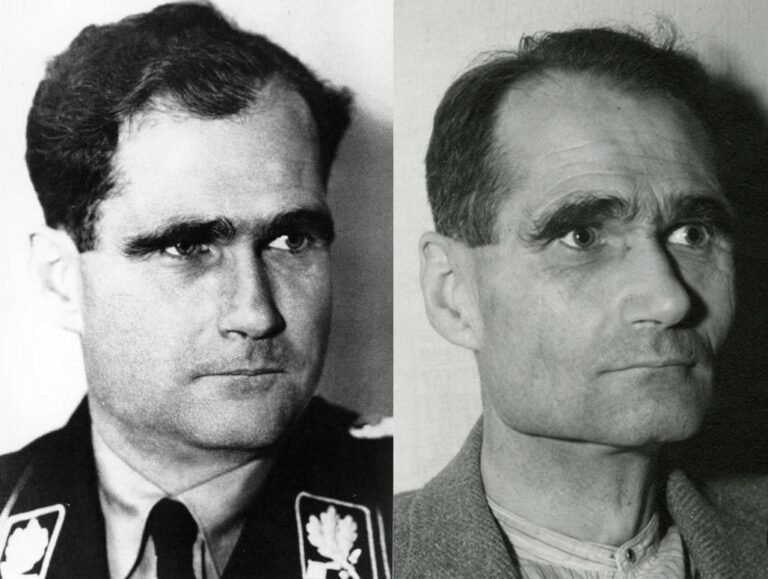

Did Rudolf Hess Really Commit Suicide? – Mythbusting Berlin

On a summer’s day in 1987, the last Nazi war criminal of the Nuremberg trials was found dead in a prison built for hundreds, yet for two decades, housed only him. The official verdict was suicide, a straightforward end to a life defined by fanaticism, delusion, and contradiction.

But the simplicity of the report belied the complexity of the man and the 46 years he had spent in Allied custody. In the meticulously controlled

Did The Nazis Develop Nuclear Weapons? – Mythbusting Berlin

The Nazi obsession with super-weapons became so serious in the closing stages of the Second World that Adolf Hitler personally believed that such ‘Wunderwaffen’ both existed in a usable form – and would save the country from defeat. Had the Nazis managed to develop nuclear weapons by 1945 – the outcome of the war would surely have been different. But how close were Hitler, Himmler, and his henchmen to developing an A-bomb?

Did The Nazis Invent Decaf Coffee? – Mythbusting Berlin

Persistent rumors claim that Nazis preferred their coffee anything but pure, leading some to wonder if they might have influenced the development of decaffeinated coffee. Although decaf was already widely available across Europe by the mid-20th century, speculation continues: could the Nazis really have played a role in popularizing—or even discovering—this caffeine-free alternative, or is this simply another caffeinated conspiracy cooked up to sensationalize an ordinary historical detail?

Did The Nazis Invent The Bicycle Reflector? – Mythbusting Berlin

The fruits of wartime ingenuity are plenty – so many, in-fact, that it has become somewhat of a worn cliche that as the guns start firing the innovators get to work, often solving problems while providing more problems for the enemy to overcome.The kind of progress that results in the production of newer improved, more lethal weapons, such as to increase the chances of victory.

Did The Nazis Run The Largest Counterfeiting Operation In History? – Mythbusting Berlin

During the Second World War the Nazis masterminded an astonishing plot to destabilise Britain by flooding its economy with counterfeit banknotes. Crafted in secret by concentration camp prisoners, this forged fortune became the most ambitious counterfeiting operation ever attempted. But was it history’s largest? Dive into the extraordinary tale of Operation Bernhard,

rife with deception, survival, and intrigue—revealing the truth behind one of the Third Reich’s most audacious schemes and its surprising legacy.

Did The Second World War End In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

When is a war ever truly over? When the last shot is fired in anger would seem like the best measure. Rarely, though, is it possible to gain insight into such a moment.

Remarkably, a record still exists of such a moment at the end of the First World War on the Western Front. A seismic register and recording of the last belching battery of British guns firing artillery across no-man’s-land, followed by a profound

Did The Spanish Flu Pandemic Help The Nazis Take Power? – Mythbusting Berlin

The devastating Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918-1919 struck amid Germany’s post-war turmoil, compounding social instability, economic hardship, and widespread political disillusionment. Could this catastrophic health crisis have indirectly paved the way for Nazi ascension? While often overshadowed by war and revolution, the pandemic’s profound psychological and societal impacts arguably contributed to the perfect storm, enabling extremist ideologies—including Nazism—to gain popularity and ultimately seize power in a fractured Germany.

Have Adolf Hitler’s Remains Been DNA Tested? – Mythbusting Berlin

In the smouldering ruins of Berlin in 1945, the world’s most wanted man vanished. Did Adolf Hitler, as official history attests, die by his own hand in the Führerbunker? Or did he escape, fuelling a thousand conspiracy theories that have echoed for decades? For years, the Soviets claimed to hold the gruesome proof of his death: a skull fragment and a set of teeth, locked away in Moscow archives. But in an age of definitive

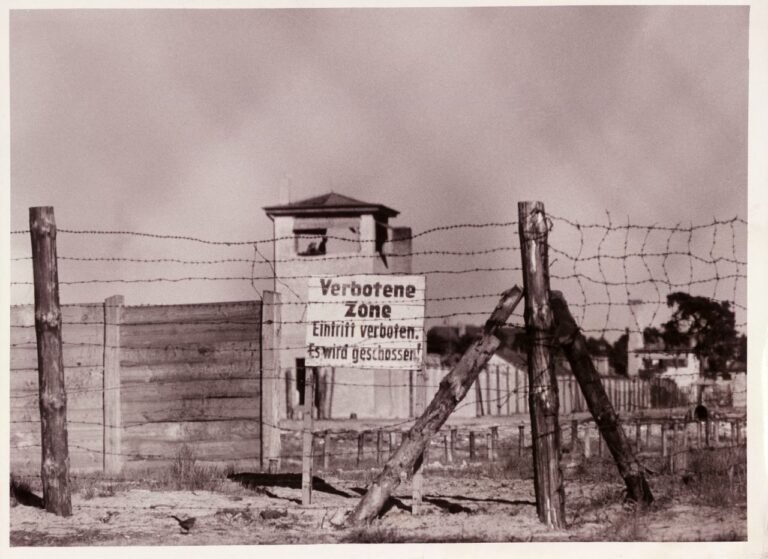

How Did The Nazi Concentration Camps Differ From The Soviet GULAG?

The Nazi concentration camps and Soviet Gulag system have often been conflated in popular imagination—twin symbols of twentieth-century totalitarian horror. Yet the two systems operated on fundamentally different principles. One extracted labor to fuel industrialisation while accepting mass death as collateral damage; the other evolved into purpose-built machinery of genocide. Understanding these distinctions isn’t merely academic—it reveals how different ideologies produce different atrocities, and why Germany and Russia reckon with these legacies so differently today.

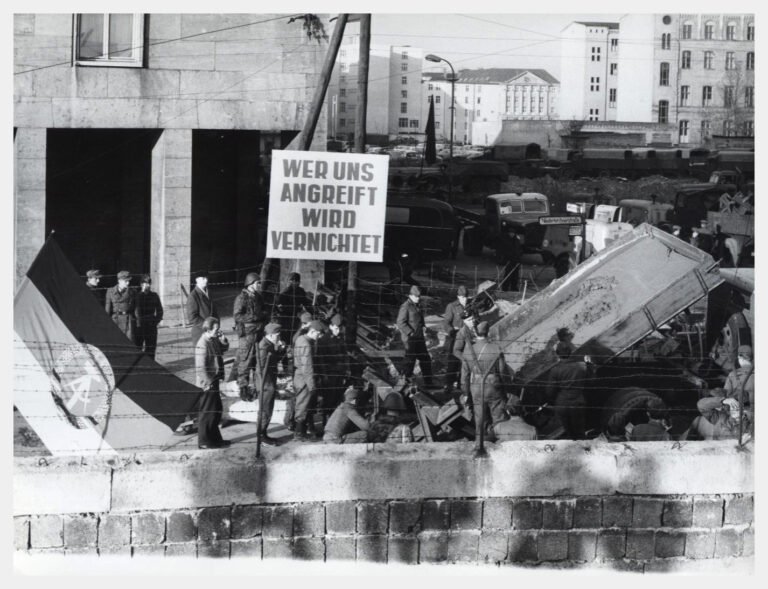

How Long Did It Take To Build The Berlin Wall? – Mythbusting Berlin

It is one of the most enduring images of the 20th century: a city divided overnight. The popular narrative tells us that Berliners went to sleep in a unified city and woke up in a prison. While the shock of August 13th 1961, was very real, the idea that the ‘Wall’ appeared instantly is a historical illusion. The physical scar that bisected Berlin was not a static creation, but a living, malevolent beast that evolved

How Many Assassination Attempts On Adolf Hitler Were There? – Mythbusting Berlin

Nazi leader, Adolf Hitler, projected an aura of invincibility, a man of destiny shielded by providence. But behind the carefully constructed image of the untouchable Führer lies a story of constant threat, of bombs that failed to detonate, and errant bullets that missed their mark. Unearth the hidden history of the numerous attempts on Hitler’s life as we explore the courage of those who tried to change the course of history and the devil’s luck

How Many Jews Died In The Holocaust? – Mythbusting Berlin

The answer to the question posed of how many Jews died in the Holocaust is a simple one: too many. That merely one death was an unforgivable obscenity is a fundamental and necessary realisation in understanding the capriciousness of this unparalleled racial genocide. To comprehend, however, the full number of Jews murdered in Europe by the Nazi regime in the 1930s and 1940s is a detective story of epic proportions: the evidence overwhelming, multifaceted, and

How Many People Died Trying To Escape East Germany? – Mythbusting Berlin

The image of the Berlin Wall is seared into our collective memory, a concrete symbol of Cold War oppression. We think of the daring escapes and the tragic deaths of those who failed. But that well-known number is only a fraction of the truth. The story of those who died trying to escape East Germany is far broader and more complex than most imagine, stretching along a thousand-kilometer border and out into the cold waters

How Old Is Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

A relatively new arrival in Europe, Berlin is over 1000 years younger than London, nevermind Rome or Athens, Jerusalem or Jericho. Just how old is Berlin though?

A question fraught with false assumptions and distortions – that has more often than not been answered with propaganda as it has with the cold hard truth.

Was Adolf Hitler A Drug Addict? – Mythbusting Berlin

Solving the enigma of the ‘Führer’ has become a preoccupation for many, since the arrival of the Austrian-German onto the world stage – although moving beyond the mythology without falling into the trap of prejudically extrapolating on the psychopathography of Hitler or demonising so as to excuse his actions has proven problematic. What to make of the man who became more than the sum of his masks? The painter; the military dilettante, the mass murderer,

Was Adolf Hitler A Freemason? – Mythbusting Berlin

History abhors a vacuum, but adores a mystery. Such is the speculative fiction suggesting a secret allegiance behind the rise of the Third Reich – that the catastrophe of the Second World War was orchestrated from the shadows of a Masonic lodge. The image of Adolf Hitler—the drifter from Vienna turned dictator—as a covert initiate of the very brotherhood he publicly reviled, however, creates a paradox that collapses under scrutiny. As when we unlock the

Was Adolf Hitler Gay? – Mythbusting Berlin

In the shadowy corridors of Third Reich history, few questions provoke as much tabloid curiosity and scholarly exasperation as the sexuality of Adolf Hitler. For decades, rumors have swirled—whispered by political enemies in 1930s Munich, psychoanalyzed by American spies in the 1940s, and sensationalized by revisionist authors today. Was the dictator who condemned thousands of men to concentration camps for “deviant” behavior hiding a secret of his own? By peeling back the layers of propaganda,

Was Adolf Hitler Jewish? – Mythbusting Berlin

Was the dictator who orchestrated the murder of millions of European Jews secretly one of them? It is perhaps the darkest irony imaginable, a story whispered for decades in backrooms, bars, and conspiracy forums alike. The most-common rumour – the ‘Frankenberger Myth’ – suggests that Adolf Hitler’s paternal grandfather was Jewish, a secret so damaging it could have unraveled the entire Nazi regime. But where does this claim come from? And, more importantly, is there

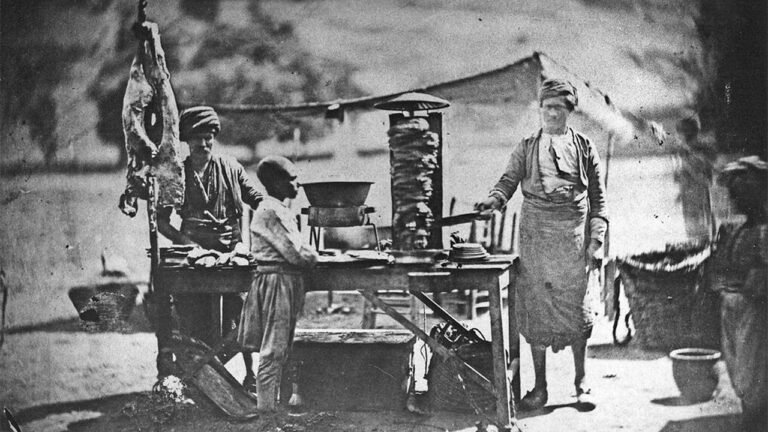

Was Currywurst Invented In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

Explore the story behind what many consider Berlin’s most iconic snack—the ever-so-humble Currywurst. Often hailed as an enduring symbol of culinary creativity amid Cold War scarcity, this humble dish has inspired fierce debate about its true origin. But was it genuinely invented here in Berlin, or have proud locals simply adopted and elevated this spicy street-food favorite into legendary status all their own?

Was Fanta Invented By The Nazis? – Mythbusting Berlin

As one of the most secretive organisations in the world, the Coca Cola corporation refuses to share its secret recipe with anyone. Famously insisting only on shipping the base syrup of its drinks to plants around the world to be carbonated and distributed.

This combined with the trade limitations of the Second World War may have led to the introduction of one of the most popular soft-drinks in the world. But could it be true:

Was Frederick The Great Gay? – Mythbusting Berlin

Frederick II of Prussia, better known as Frederick the Great, is often remembered as the archetypal enlightened monarch – a brilliant military commander, patron of the arts, and learned philosopher. Yet behind the stern portraits of this 18th-century warrior-king lies a personal life long shrouded in intrigue and speculation. Intrigue around the king’s sexual orientation has persisted through the centuries, chiefly revolving around one question: Was Frederick the Great gay?

Was Henry Ford A Nazi? – Mythbusting Berlin

US auto tycoon, Henry Ford, holds the ignominious distinction of being the only American Adolf Hitler praised by name in his National Socialist manifesto: ‘Mein Kampf’. This was not, as it turns out, the only connection between Ford and the Party of Hitler, Himmler, and the Holocaust.

Ford’s overt affinity with the Third Reich reveals a troubling past. How deep these connections ran, and how consequential they were for both sides, is a chapter

Was The Colour Blue Invented In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

Tracing the true history of blue—from ancient Egyptian dyes to the accidental discovery of Prussian Blue in a Berlin lab. We’ll debunk myths about seeing blue, explore colonial indigo plantations, scale mountains with a cyanometer, and trace Van Gogh’s starry skies—all to answer one question: how did Berlin shape our understanding of the world’s rarest color?

Was The Döner Kebab Invented In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

Unlikely icon of immigrant success; fast food symbol of the working class; over-hyped midnight disco eat; or culturally appropriated cuisine? Its influence goes far beyond layers of seasoned meat and fresh vegetables stuffed into pita bread. But does Berlin deserve credit as the Döner Kebab’s true birthplace, or has the city merely refined and popularized a culinary tradition imported from elsewhere?

Was The Fall Of The Berlin Wall An Accident? – Mythbusting Berlin

On a seasonally crisp night in November 1989, one of the most astonishing events of the 20th century occurred. After twenty eight years, three months, and twenty eight days of defining and dividing the German capital, the Berlin Wall ceased to exist – at least in an abstract sense. Although the removal of this symbol of the failure of the East German system would take some time, its purpose – as a border fortification erected

Was The Nazi Party Democratically Elected? – Mythbusting Berlin

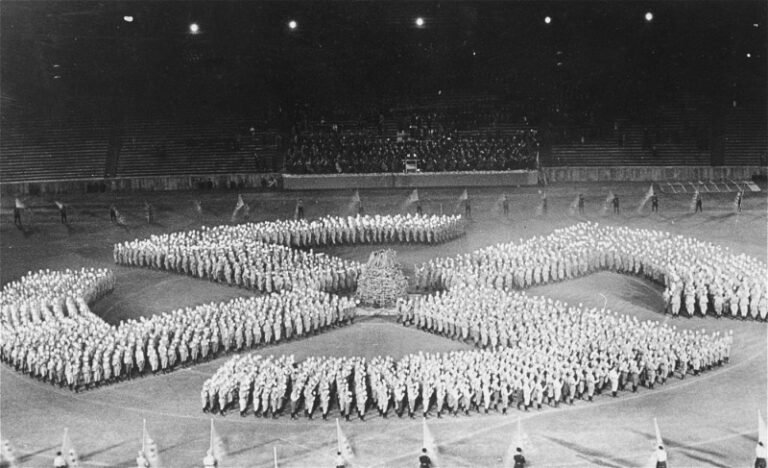

The myth persists that Adolf Hitler rose to power through popular democratic choice. Yet history reveals a darker, more complicated truth. Hitler’s ascent involved exploiting democratic institutions, orchestrating violence, propaganda, and political intrigue—not a simple election victory. Understanding how Germany’s democracy collapsed into dictatorship helps illuminate the dangerous interplay between public desperation, elite miscalculations, and extremist ambition, providing crucial lessons for safeguarding democracy today.

Were The Allied Bombings Of Germany War Crimes? – Mythbusting Berlin

The history of the Allied bombing of Germany during the Second World War still triggers fierce debate. Was reducing cities to rubble a necessary evil – justice from above in a just war – or an unforgivable crime? Can the intentional targeting of civilians ever be justified as militarily necessary?

In a conflict where all rules seemed to vanish, an even more pertinent question persists: by the very standards they would use to judge their

Were The Nazi Medical Experiments Useful? – Mythbusting Berlin

Before the Nazi period, German medicine was considered the envy of the world – a shining monument to progress. But deep within that monument, a rot was spreading, one which would collapse the entire structure into an abattoir. From the wreckage, we are left with a profoundly uncomfortable inheritance: a moral enigma wrapped in doctor’s whites.

What to make of the data, the images, and the terrible knowledge gleaned from unimaginable human suffering. Whether

What Are The Origins Of The Nazi Salute? – Mythbusting Berlin

A specter is haunting the modern mind, a gesture so charged with the dark electricity of history that its mere depiction can unleash a storm of controversy.

It is a simple movement: the right arm, stiff and straight, raised to the sky. But in that simplicity lies a terrifying power, a symbol of a regime that plunged the world into an abyss and a chilling reminder of humanity’s capacity for organised hatred.

This

What Are The Origins Of The Nazi Swastika? – Mythbusting Berlin

Long before the legions of the Third Reich marched beneath its stark, unnerving geometry, the swastika lived a thousand different lives. It was a symbol of breathtaking antiquity, a globetrotting emblem of hope and good fortune that found a home in the most disparate of cultures. To even begin to understand its dark 20th-century incarnation, one must first journey back, not centuries, but millennia.

What Are The Pink Pipes In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

A first-time visitor to Berlin could be forgiven for thinking the city is in the midst of a bizarre art installation. Bright pink pipes, thick as an elephant’s leg, climb out of the ground, snake over pavements, arch across roads, and disappear back into the earth. Are they part of a complex gas network? A postmodern artistic statement? A whimsical navigation system? These theories, all logical, are all wrong. The truth is far more elemental,

What Do The Colours Of The German Flag Symbolise? – Mythbusting Berlin

What does a flag mean? Is it merely a coloured cloth, or does it hold the hopes, struggles, and identity of a nation? The German flag, with its bold stripes of black, red, and gold, is instantly recognisable. But the story of its colours is a tumultuous journey through revolution, suppression, and reinvention. The common explanation for their symbolism is a simple, romantic verse, yet the truth is a far more complex and contested tale,

What Happened To Adolf Hitler’s Alligator? – Mythbusting Berlin

It is often said that you can tell a lot about a person by their relationship with animals; that owners often come to look and behave like their pets. Or is it perhaps more that people choose their pets to correspond to their personality? Nazi leader Adolf Hitler’s love of dogs, for example, is well documented but what is there to make of his relationship with reptiles?

What Happenened To The German Royal Family? – Mythbusting Berlin

When the smoke cleared over the trenches in November 1918, the German Empire had evaporated, and with it, the divine right of the Hohenzollern dynasty. Conventional wisdom suggests the family simply vanished into the sepia-toned obscurity of history books—exiled, forgotten, and irrelevant. But dynasties, like weeds in a landscaped garden, are notoriously difficult to uproot entirely. The story of the German royals did not end with the Kaiser’s flight to Holland; it merely shifted gears.

What Is The Difference Between Fascism & Nazism? – Mythbusting Berlin

While the terms ‘Fascist’ and ‘Nazi’ are often bandied around interchangeably as shorthand for tyranny – Italian fascism and German National Socialism were distinctly different beasts. Albeit ideological kin. One an ideology of state-worship, born from post-war chaos and national pride; the other built upon a fanatical, pseudo-scientific obsession with race. Two peas in the same totalitarian pod – twins in tyranny – more succinctly summarised as the Nazi chicken to the Fascist egg.

What Was Checkpoint Charlie? – Mythbusting Berlin

Checkpoint Charlie remains among Berlin’s most visited historical sites, famed worldwide for its significance during the Cold War. Originally established as a modest border-crossing point, it evolved dramatically over the decades into an international symbol of freedom, espionage, and intrigue. Today, critics and locals often dismiss it as little more than a tourist trap—Berlin’s Disneyland—but how exactly did Checkpoint Charlie get its peculiar name, and what truths hide behind its popularity?

What Was Prussia? – Mythbusting Berlin

Prussia’s legacy is both remarkable and contentious—once a minor duchy, it rose dramatically to shape modern European history. Renowned for military discipline, administrative efficiency, and cultural sophistication, Prussia was instrumental in uniting the German states, laying foundations for a unified Germany. But how did this kingdom, with its roots in Baltic territories, achieve such prominence, and why does its complex history continue to evoke admiration, debate, and occasional discomfort in Germany today?

What Was The Berlin Airlift? – Mythbusting Berlin

In the ruins of 1948, the silence of Berlin was not a sign of peace, but a held breath before a new catastrophe. The city, drowning in rubble and political intrigue, became the staging ground for the twentieth century’s most audacious gamble. While popular history remembers the chocolate parachutes and smiling pilots, the reality of the Berlin Airlift was a terrifying operational nightmare born from a ruthless currency war. It wasn’t just a humanitarian mission;

What Was The Socialist Kiss? – Mythbusting Berlin

It is one of the most curious and enduring images of the Cold War: two middle-aged, grey-suited men, locked in a fervent embrace, their lips pressed together in a kiss of apparent revolutionary passion. This was the ‘Socialist Fraternal Kiss’, a ritual that, for a time, seemed to encapsulate the unwavering solidarity of the Eastern Bloc.

But what was behind this seemingly intimate gesture? Was it a genuine expression of camaraderie, a piece of

Who Built The Berlin Wall? – Mythbusting Berlin

One of the most common questions I have encountered from people curious about Berlin, and often so cryptically phrased. Who built the Berlin Wall? A simple five-word query, yet one that can be read one of two ways. More than thirty years since the ‘Fall of the Wall’, the story of its construction continues to baffle many who are mainly familiar with its existence through knowledge of its importance…

Who Really Raised The Soviet Flag On The Reichstag? – Mythbusting Berlin

One iconic photograph has come to symbolise the Red Army’s victory over Nazi Germany in 1945—the Soviet flag waving triumphantly above Berlin’s battered Reichstag building. Yet behind this enduring image lies controversy, confusion, and political manipulation. Who truly raised the Soviet banner atop the Reichstag? Was it a spontaneous act of heroism or carefully staged Soviet propaganda? Decades later, unraveling the truth reveals surprising layers beneath the mythologized symbol of Soviet triumph.

Who Was Really Responsible For The Reichstag Fire? – Mythbusting Berlin

Various theories have been posited as to who actually set fire to the German parliament in 1933. Was it the opening act in an attempted Communist coup or a calculated false flag operation carried out by elements of the Nazi Party, intended to create the conditions necessary for introducing single-party rule? And what part did the young man from Holland, arrested shirtless inside the building the night of the fire, play in this event?

Who Were The Last Nazis On Trial? – Mythbusting Berlin

More than eighty years after the Holocaust, courtrooms across Germany still echo with testimony from the final chapter of Nazi justice. Centenarian defendants in wheelchairs, their faces hidden behind folders, arrive to answer for crimes committed in their youth. These are not the architects of genocide—those men faced their reckoning at Nuremberg decades ago. These are the guards, the secretaries, the bookkeepers: ordinary people who enabled extraordinary evil. Their trials represent a legal revolution: the

Why Is Berlin The Capital Of Germany? – Mythbusting Berlin

There was little in its humble origins—as a twin trading outpost on a minor European river—to suggest that Berlin was destined for greatness. It sits on the flat expanse of the North European Plain, a landscape once dismissively referred to as the “sandbox of the Holy Roman Empire.” Unlike other world capitals, it lacks breathtaking scenery or a naturally defensible position. It is a city built not on majestic hills or a grand harbour, but