“Let nothing be called natural

In an age of bloody confusion,

Ordered disorder, planned caprice,

And dehumanized humanity, lest all things

Be held unalterable!”

Bertolt Brecht

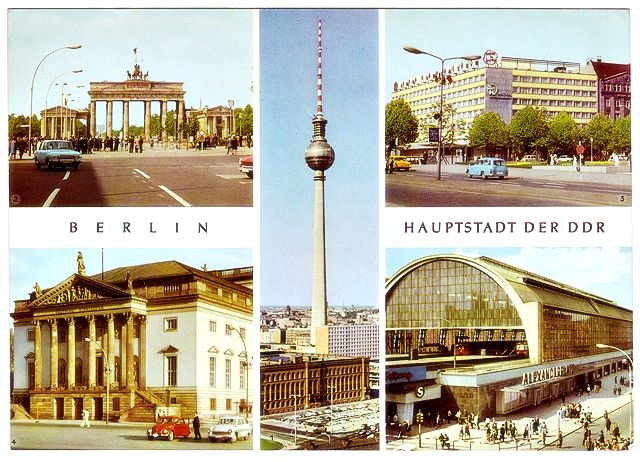

The Berlin Wall was without doubt doomed from its conception.

As a punitive exercise in population control, the question of its demise not so much a matter of whether but simply when. And under which conditions.

There is little evidence that human beings want to be restricted in their freedom of movement – or their ability to define themselves by their own desires. In-fact, there is much to the contrary. The totalitarian temptation, the urge to live subordinate and servile – as French philosopher Jean-François Revel described it back in 1976 – is not universal.

Irrespective of whether the defective conditions created by the East German government in its pursuit of an authentic Socialist society were merely manifestations of the true nature of its Marxist-Leninist ideology or accidental deviations – something was clearly wrong in paradise.

The East German experiment, from the moment it was first imposed on the Soviet Occupied Zone of the country, proved to be fraught with problems. Least of all the tendency exhibited by citizens of the German Democractic Republic to vote with their feet – against single party rule, against the underperforming command economy, and against the increasingly draconian and repressive actions of the state carried out to ensure its continued existence.

- Within the first three years following the establishment of East Germany in 1949 some 675,000 people would flee the country.

- In-fact, the first five years following the end of the Second World War saw around 15 million people migrate from the Soviet occupied areas of Eastern Europe to the states in the West. A number approximately equivalent to the modern day population of the Netherlands.

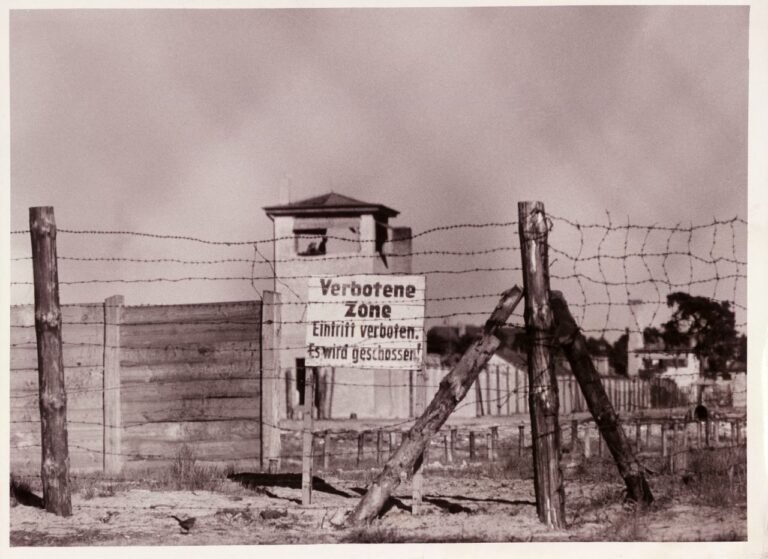

In resolving to deal with this exodus, the East German government moved to close off its border with West Germany in 1952. A measure justified as necessary to combat “spies, diversionists, terrorists and smugglers”. The so-called Iron Curtain had begun to take shape; now in the form of a militarized frontier dividing the countries of Eastern Europe from those in the West.

Three years earlier, the Hungarian government had actually already undertaken a similar operation – erecting 260km of barbed wire fence along its border with Austria.

Fittingly, it would be here in 1989 that the first gap in the East-West frontier would appear.

Over the course of the next four decades of the Cold War, however, this Iron Curtain would grow to a 7,000km long physical barrier of fences, walls, minefields, and watchtowers.

Although, following the construction of the Inner German Border (as the stretch of the Iron Curtain dividing East and West Germany would be known), the citizens of East Germany would be afforded a remarkable opportunity to continue their exodus from the country. The possibility of simply crossing into the British, French, and American zones within the GDR – and escaping via West Berlin.

Hundreds of thousands would, through this unusual arrangement, make their voices of opposition clearly heard. Those who chose – in their rejection of the East German system – to resettle alongside their fellow German brothers and sisters in the more prosperous West.

This mass emigration of citizens eventually grew into a very real threat to the existence of the German Democratic Republic. So many of the country’s brightest and most promising were abandoning the Workers’ and Peasants’ state. The construction of the Berlin Wall in August of 1961 would be East Germany’s desperate solution to stem this tide; as the country desperately fought for its survival.

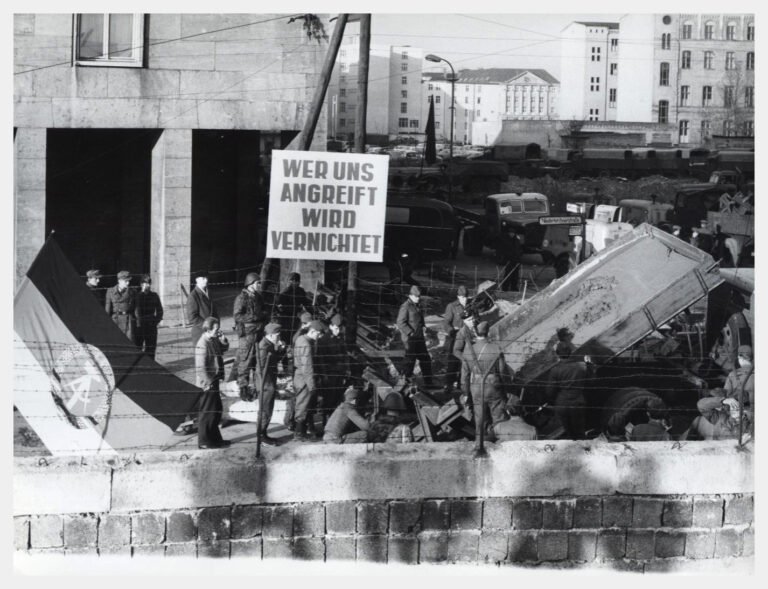

‘Barbed Wire Sunday’ – as it would be termed by the West Berlin press – was intended to resolve this situation once and for all.

Although in constructing the Wall, the East German state, and its ruling Socialist Unity Party, was not acting to address the issues in the country that were driving people to leave – merely duct taping a wound. And introducing further problems in the process.

Not to mention creating a towering expression of its failings.

A physical embodiment of paradise lost.

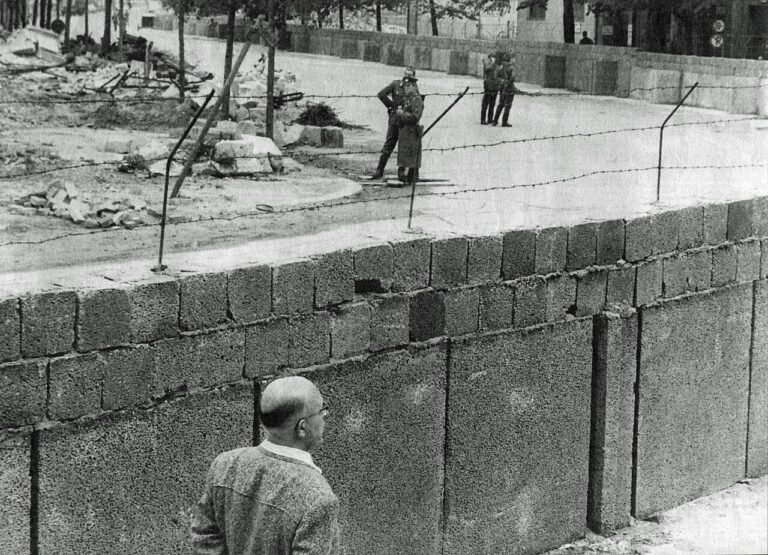

By definition, however, the Berlin Wall never truly lived up to its description. The first incarnation of this barrier, as it was introduced on August 13th 1961, was not in-fact a wall but a series of barbed wire fences and connecting poles. Despite the anti-capitalist pontificating of the East German state, much of the former had to be bought in bulk from British suppliers through shell companies – the latter sometimes even consisting of reappropriated washing line posts due to material shortages.

Only later in the month would this grow into the iconic breezeblock wall topped with barbed wire, so recognisable of this period. Truly, it was only one Wall in the minds of the Western visitors who would encounter it at street level; observing the three-metre-high concrete manifestation of this project the East Germans had lassoed around the British, French, and American sectors of the city.

The development of the Berlin Wall would take decades, the haphazard nature of its growth an indication of how imperfectly conceived the project was – no comprehensive plan for an impenetrable frontier was produced by the East German state in 1961. At least not illustrating the form it would later take. It had to be improved in relation to the threat and opportunity offered to potential escapees by its flaws.

The ‘Fall of the Berlin Wall’ would be similarly ill-conceived; although unlike in 1961 where its construction was the result of a coordinated government strategy; its redundancy in 1989 would be announced by a regime that in-fact had little intention of bringing about its immediate obsolescence.

–

The Ouroboros Is Broken - It’s The Economy, Stupid

“Forget not the tyranny of this wall; nor the love of freedom that made it fall”

Graffiti on the Berlin Wall

Much emphasis when analysing the downfall of East Germany has been placed on the socio-political factors in the country; while largely overlooking one incredibly important – and ultimately decisive – factor.

The economy, stupid.

The weighty tomes of Communist writers struggling to deal with monetary theory undoubtedly stand as their most impenetrable works. Certainly, the treatise that Karl Marx died before completing – Das Kapital – although considered a foundational text of the modern labour movement, remains too complex for a painless appraisal.

Marx’s fellow firebrand and benefactor, Friedrich Engels, who undertook to stitch together the final two parts of Das Kapital, would famously refer to money as the ‘corrosive acid’ that breaks apart societal bonds.

The question of money – and its use – would prove to be yet another circle that the East German state would fail to square.

Of course, the economic problems in East Germany, were not much different to those in the other Marxist-Leninist states of Eastern Europe that had mushroomed under the paternal guidance of the Soviet Union following the end of the Second World War. In particular, as the very engine that had propelled the peasant society of Bolshevik Russia to superpower status – the industrial planned economy – increasingly came to exert a drag.

While Marx had envisioned an economy based on co-operation on human need and social betterment, whether he would have approved of the kind of centrally planned command economy eventually adopted by the Soviet Union and its satellite states has been passionately debated sine die by his acolytes since his death.

Marx asserted that the transition from capitalism to communism would take place quicker when a society was already sufficiently industrialised – one of the reasons why he believed the Proletariat revolution would take place in Germany first, and not Russia. Even if it eventually would take place the other way around.

Industrialisation, economic centralisation, and collectivisation of agriculture would be the central tenets of the Soviet Union’s first Five Year Plan for the development of the national economy from 1928 until 1932. As in the Soviet Union, increasing the volume of heavy industry production in particular was seen as important in East Germany in ensuring economic dependency from the capitalist countries of the West.

But what – once a country is sufficiently industrialised and control of the means of production have been centralised in the hands of the workers – comes next?

Certainly, the standard of living in East Germany did increase through the 1960s and 70s – even if not as significantly as in West Germany – largely as the country proved to be relatively successful as an exporter to the West and actually chose to implement market-based reforms to its internal economic policy. However, following a global rise in commodity prices in the 1970s – and a calamitous reversion to the economic goal of industrial progress through central planning – the country’s growing hard currency debts soon became a major cause of domestic instability. The late 1960s had indeed brought an increase in real wages and the supply of consumer goods, including luxury items, in the country – but just as East Germany seemed to be offering its citizens a more inspiring vision of consumer-influenced socialism, it began spiraling into debt.

In 1970, East German leader Walter Ulbricht had prematurely, and somewhat bizarrely, boasted that the country would overtake the Western economies “without catching them up”. Although by some estimates the German Democractic Republic would become not only the strongest economy in the Eastern bloc but one of the strongest worldwide – it would fail to establish lasting financial stability.

Instead its seemingly irreversible economic decline precipitating its eventual demise.

Beyond suffering from the shortcomings of its command economy, East Germany had been tainted from the outset by the post-war reparations and occupation costs demanded by the Soviet Union. Cut off from the raw materials and intermediate goods that the east of German had historically depended on from its western part, and burdened with absorbing also the debts of its East Bloc counterparts when bills could not be paid in full. The agrarian reforms and nationalisation measures in the country’s early years proved to have been carried out for ideological reasons – failing to guarantee long-term economic security. The collective people’s farms (Landwirtschaftliche Produktionsgenossenschaft – LPG) and industrial “People’s Enterprises” (Volkseigene Betriebe—VEB) would succeed in driving away farmers with large tracts of land, increasing emigration in general, and introducing work and production quotas that many considered unrealistic. While inflicting on the workplace a sense of malaise and inertia – compounded by a lack of reward for problem solving and innovation – the country would struggle to overcome.

Undoubtedly the most significant ingredient in the country’s economic stew was its relationship with the Soviet Union – the measure of which did much to dictate the condition of East Germany’s budget. Particularly as the country profited through the resale of cheap Soviet crude oil – something that would grow to become less profitable due to changes in the world economy. New leadership in Moscow by the mid-1980s would also mean an end to the kind of economic intervention that had helped prop up the country – and fill in the blanks in its ledger – during the Khruschev era.

As the German Democratic Republic hurtled towards the economic abyss, a paper prepared for the country’s ruling Politburo in the late-1980s made the situation painfully clear: an increase in exports by 500% would be necessary in order to stabilise debt levels.

An impossible feat.

As British author Frederick Taylor explains: “In the 1980s, when according to the economic plan the country was supposed to be turning into a high-tech, R&D based modern powerhouse, the story had in fact been one of a steady decline and increasing foreign indebtedness.

The GDR could only imitate, not innovate.”

The tangible menace of social and political unrest in East Germany had appeared earlier in 1953, following Joseph Stalin’s death, in the form of a nationwide uprising – only to be stomped out by Soviet troops, much as would happen in Hungary in 1956 and Czechoslovakia in 1968. As a result, the country would come to prioritise the repression of its own people, ensuring decades of simmering resentment and frustration before this eventually boiled over in the late 1980s.

While the effectiveness of the East German State Security Police grew – the borders remained firmly secured, dissidents observed or imprisoned, and a cadre of informants and collaborators fostered – the threat of Soviet military intervention to deal with political unrest in the country remained ever-present.

Yet, another – less visible – enemy was slowly eating away at the country from within. One that could not be defeated with tanks and soldiers.

By the mid-1980s, the trajectory of East German’s financial ruin was already well established. With the underlying economic conditions that would ensure the downfall of the state and its ruling ideology firmly in place.

–

Annus Mirabilis - The Miraculous Year- 1989

“What no one understood, at the beginning of 1989, was that the Soviet Union, its empire, its ideology – and therefore the Cold War – was a sandpile ready to slide. All it took to make that happen were a few more grains of sand. The people who dropped them were not in charge of superpowers or movements or religions: they were ordinary people with simple priorities who saw, seized, and sometimes stumbled into opportunities. In doing so, they caused a collapse no one could stop. Their “leaders” had little choice but to follow.”

John Lewis Gaddis

It was to be the two hundredth anniversary of the French revolution; two centuries since the storming of the Bastille. A year for celebrating the abolition of the Ancien Régime, the abrogation of French dynastic rule, the toppling of absolutism, and an end to the country’s oppressive feudal system.

To the peasants, who made up the largest part of France’s population at the time, practical matters such as food shortages and ruinously high taxation appeared in urgent need of redress. But it would be the offensively decadent lifestyles of the ruling elite and their detachment from the reality faced by the majority of French society, that would come to act as the most powerful accelerant of the revolutionary fire.

The ideas of Enlightenment-era philosophy would serve as a further catalyst – with Thomas Jefferson, who witnessed the year’s events in Paris while serving as Minister to France, assisting in drafting a ‘Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen’. As a core statement of the values of the French Revolution, the Declaration would come to be seen as a definitive formulation of the doctrine of secular natural law – evident from its opening article that “Men are born and remain free and equal in rights.”

This intersection of utopian aspiration and bread-and-butter grievances, however, would result in the bloodsoaked transformation of French society from 1789 – as traditional order was overthrown and thousands perished in a reign of terror. Culminating in the appointment of Napoleon Bonaparte as the First Consul of the French Republic.

Assessing thee events, Karl Marx would refer to the French Revolution as the “most colossal revolution that history has ever known”.

Undoubtedly, the French Revolution was one of the greatest events in human history and an inexhaustible source of instruction for any student of history on the strength of ideas, the extent of their reach, and the hazards of their implementation. A warning from the past of how good intentions can lapse into purges, mass murder, and war.

As protest across Eastern Europe – against the regimes that laid claim to being representative manifestations of Marx’s ideas of earth – grew in 1989, the question of whether the outcome would be as tragic or bloody as what had occured two hundred years previously remained to be seen. What in retrospect can be stated, is that at the time few knew how close they were to the end – or how exactly it would come.

Marx himself claimed to have a great sense of the direction of history; that the material conditions of life and individuals’ relationship with modes of production would determine the course of the future. And that future would be a transition from capitalism to socialism, before reaching true communism as the final stage of human societal development.

But by February 1981, the Soviet transition to communism – which had been announced under Nikita Khruschev’s leadership as feasible by 1980 – had been publicly abandoned.

The implementation of Marx’s ideas, cast through the lens of Lenin, and with the added paranoia and butchery of Stalin had – in its place – seen the establishment of an authoritarian state prepared to mercilessly stomp out opposition in the quest to further its ideological ambitions. The ‘Dictatorship of the Proletariat’, the command economy, and the transformation of Eastern Europe into a glorified concentration camp had not brought the Soviet Union any closer to its goal of true communism. The ‘classless society’ could not shake off the trappings of individual difference and personal motivation.

As Stephen Kotkin succinctly notes: “Russia’s socialist revolution, having originated in a radical quest for egalitarianism, produced an insulated privileged class increasingly preoccupied with the spoils of office for themselves and their children.”

By mid-way through the 1980s, the Soviet Union would be a visibly sinking ship. Overstretched and fighting a losing war in Afghanistan, struggling to assure the world of the relevance of its ideology, and stay afloat economically whilst falling behind the more prosperous West.

In 1985, a new captain would take control and attempt to steer the Soviet Union into calmer waters – while endeavouring to avoid running aground on the perilous rocks of reform before reaching a safe harbour. For the first time, here was a leader born after the 1917 Revolution; who had grown up entirely within the Marxist-Leninist system. The members of the aging Politburo hoped that after being handed the reigns of power this relatively fresh face would tone down his calls for transforming the Soviet system.

The man who would go down in history as the last general secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union – Mikhail Gorbachev – would severely disappoint them.

Gorbachev believed radical reform was necessary for the survival of the Soviet Union; soon introducing the world to the terms: Glasnost (Openness), Perestroika (Restructuring), and Uskoreniye (Acceleration). Although decisive in his role; it could be argued that his greatest contribution to the unexpected developments of the late 1980s in Eastern Europe was largely a matter of what he did not do.

When the long standing Hungarian leader, János Kádár, was forced to retire in 1988, the new government established a commission to reassess the events of 1956 – when Soviet troops had violently crushed an uprising in the country. Concluding that this had been a “popular uprising against an oligarchic system of power which had humiliated the nation”, the Hungarian state swiftly organised a state funeral for former premier, Imre Nagy, who had led the uprising and was as a result executed. Two hundred thousand people attended Nagy’s reburial. Gorbachev did not disapprove. Soon after, the new Hungarian prime minister, Miklós Németh, refused to allow further funds for the frontier section of Iron Curtain separating Hungary from Austria, across which the refugees of 1956 had attempted to flee. In April 1989, the government ordered the electricity in the barbed-wire border fence to be turned off. Declaring the current barrier a health hazard, the Hungarians began to dismantle the frontier the following month.

When in Poland, a ‘non-confrontational’ election was held for the new bicameral legislature in 1989, the banned trade union Solidarność took 99% of the Senate and all but one of the seats in the lower house.

On August 24th 1989, the first non-communist government of postwar Eastern Europe formally took power in the country.

Meanwhile, the East German government looked on unwavering – single party rule had been confirmed in May 1989 with the re-election of Erich Honecker – who received a mere 98,95% of the vote. Responding to the changes afoot in the Soviet Union, the East German state intending to remain resolute, a conviction represented in the statement from a government official critical of Gorbachev’s Perestroika: “Just because your neighbour changes his wallpaper, does not mean you need to change yours.”

Many of the people of East Germany, however, had other things in mind.

The gap in the Iron Curtain in Hungary meant that thousands of East Germans had flocked to this open border, abandoned their sputtering Trabants to cross into Austria – others crowded into the West German embassy in Budapest. By September 1989, there were around 130,000 East Germans in Hungary – with the government announcing for humanitarian reasons it would not stop their emigration to the West.

Similar scenes unfolded at the West German embassy in Prague, where some 3,000 East Germans climbed over the perimeter fence and attempted to claim asylum. Eager to end this embarrassing situation, East German leader Honecker agreed to allow the East Germans to travel to West Germany. But only on sealed trains travelling through the GDR, allowing the East German leader to claim the train’s occupants were being expelled from the country.

The timely organised 40th anniversary of East Germany on October 7th 1989 would prove to be a further embarrassment for Honecker, who would be confronted by a crowd of marchers breaking with the official slogans to appeal to Soviet leader Gorbachev – the star guest at the commemorations. “Gorby, help us! Gorby, stay here!” Anti-government protests had in-fact been taking place across the country for weeks – especially in the city of Leipzig. Less than two weeks after the 40th anniversary celebrations, Honecker was ousted from power – in the spirit of comradely self-sacrifice, forced to vote for his own removal – and replaced by the third and final leader of Socialist East Germany, Egon Krenz.

Krenz was actually simultaneously elected to two posts — ‘Chairman of the Council of State’ and ‘Chairman of the National Defence Council’ – meaning that he was both de-facto President and commander-in-chief of the National People’s Army. The divisive nature of his election – which otherwise would have come as a simple formality – was immediately evident. It was only the second time in the East German parliament’s forty-year history that the vote was not unanimous.

As head of state and head of the military, Krenz could have organised an armed response to the rising protests in the country – he had a few weeks earlier attended the fortieth anniversary celebration of Mao’s revolution in Beijing. The Chinese Communist Party’s brutal response in June to the student protestors who had filled the city’s Tiananmen Square to demonstrate against the country’s political direction had been applauded by the East German government. East German television repeatedly ran a documentary praising the “heroic response of the Chinese army and police to the perfidious inhumanity of the student demonstrators”.

Despite his position, Krenz would not respond to growing unrest in East Germany with force.

But with the proposed introduction of travel visas – allowing East Germans to leave the country and triggering the downfall of the Workers’ and Peasants’ state.

–

The Fall Of The Berlin Wall - The Greatest Jailbreak In History

“Perhaps the ultimately decisive factor…is that characteristic of revolutionary situations described by Alexander de Tocqueville more than a century ago: the ruling elite’s loss of belief in its own right to rule. A few kids went on the streets and threw a few words. The police beat them. The kids said: You have no right to beat us! And the rulers, the high and mighty, replied, in effect: Yes, we have no right to beat you. We have no right to preserve our rule by force. The end no longer justifies the means.”

Timothy Garton Ash

The announcement made by the East German government on November 9th that effectively nullified the Berlin Wall did not actually directly address the matter of this infamous concrete barrier.

Instead the press conference would deal with the matter of travel visas – and whether East Germans would be finally given the opportunity to leave the country without the risk of being shot at its borders. The man tasked with delivering this news was the former editor of the Neues Deutschland newspaper and SED party leader for Berlin, Günter Schabowski.

It could be argued that in his confused articulation of a Politburo directive that he had been poorly prepared to deliver, Schabowski managed to single-handedly trigger the ‘Fall of the Berlin Wall’ with the use of one German word: sofort. Immediately.

Schabowski had arrived at the International Press Centre on Berlin’s Mohrenstrasse shortly before 6pm to prepare for the day’s press conference. Half an hour earlier, he had visited Egon Krenz – the newly installed East German leader – and asked the General Secretary if they were any points to be included on the evening’s agenda. Krenz passed Schabowski a document dealing with travel restrictions that had been crafted at a party meeting earlier in the day that Schabowski had not been able to attend.

This issue of travel restrictions would be the last item on the agenda.

Although a government, not party, matter – Schabowski was nevertheless entrusted with presenting this new directive to the press.

At 6:53pm, Schabowski – sweating slightly and visibly exhausted – read through this dense government document in mechanical fashion, starting by explaining the preamble: that the new directive would “make it possible for every citizen of the GDR to leave the country using the border crossing points of the GDR.”

The decree from 30 November 1988 about travel abroad of GDR citizens will no longer be applied until the new travel law comes into force.

Starting immediately, the following temporary transition regulations for travel abroad and permanent exits from the GDR are in effect:

Applications by private individuals for travel abroad can now be made without the previously existing requirements (of demonstrating a need to travel or proving familial relationships). The travel authorisations will be issued within a short period of time. Grounds for denial will only be applied in particularly exceptional cases.

The responsible departments of passport and registration control in the People’s Police district offices of the GDR are instructed to issue visas for permanent exit without delay and without presentation of the existing requirements for permanent exit. It is still possible to apply for permanent exit in the departments for internal affairs (of the local districts or city councils).

Permanent exits are possible via all GDR border crossings to the FRG and (West) Berlin

The temporary practice of issuing (travel) authorisations through GDR consulates and permanent exit with only a GDR personal identity card via third countries ceases.

The attached press release explaining the temporary transition regulations will be issued on 10 November.

Responsible: Government spokesman of the GDR Council of Ministers

The document had been prepared at the Interior Ministry on Mauerstrasse in East Berlin by a working party of four officials, including two Stasi officers, on the morning of November 9th, at the behest of the Politburo.

The initial title for the document was ‘For the alteration of the situation regarding permanent exit of GDR citizens via the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic.’

This was subsequently changed before it was passed onto Schabowski, and the new title added: ‘Immediate Granting of Visas for permanent exit’. While the previous reference to Czechoslovakia was shifted to the preamble of the text.

The official East German government inspiration cited in the document for the introduction of these new conditions would not be Gorbachev’s Glasnost policies, the opening of the Iron Curtain on the Austria-Hungary border, or the abhorrent continued existence of the Berlin Wall, but the problematic situation that had occurred in Prague when East German citizens had stormed the West German embassy. And the public relations disaster that had followed when Erich Honecker had agreed to allow these East Germans to be evicted for the country on trains passing first through East Germany before triumphantly reaching the West.

It had taken four minutes for Schabowski to read through the text and settle once and for all the pressing issue that for more than forty years had acted as the knife at the throat of the whole East German experiment.

Leaning back in his chair, the exhausted Schabowski was not expecting further questions.

Undoubtedly, he was not fully aware of the extent of damage already done.

Nonetheless, the matter had not been fully settled to the satisfaction of the journalists in the room.

At 6:57pm on November 9th 1989, an Italian journalist queried Schabowski. Could this be some kind of mistake? Relatively unfazed, Schabowski responded by reiterating the conditions specified in the document.

The identity of the man responsible for the final – and most important – question of the press conference remains unknown. A detail thrown aside by the juggernaut of events about to unfold. Many have said that Tom Brokaw of American network NBC was that voice; although who exactly was responsible for the question is largely irrelevant. What is important is that it was asked and the response given proved to be the final grain of sand needed to unsettle the entire castle.

“When will this regulation come into effect?”

Schabowski returned to the document in front of him, placed among his own notes, and scrambled to answer:

“So far as I know, that is, uh, immediately, without delay.”

This was not correct; as the document clearly stated at the bottom of the announcement that the regulations would not come into effect until the next day, November 10th. Allowing the East German government to move – one foot forwards at a time – to address the reality and implementation of their resolution after what they expected would be a quiet evening.

On the question of the Berlin Wall, nothing was said. Whether it would continue to function as a barrier separating Berlin into two would remain to be seen. As it turns out, the next 24 hours would be unlike anything anyone in the East German government expected and finally condemn the Berlin Wall to ruin.

But as the press conference came to a close at 7:01pm, after just over one hour, even the journalists in the room seemed somewhat unaware of the true extent of significance of Schabowski’s words. Many chose to mingle with their colleagues and refuel at the nearby coffee bar. Stewing on the resolution and Schabowski’s final response.

Far from being an immediate sensation; the announcement from the East German government would first have to be clarified and broadcast by Western news outlets and received by the East German population, before anyone moved to act.

Shortly after 7pm, both Reuters and DPA broadcast the first news of the resolution over their wires, simply stating that any GDR citizen would be entitled, from now on, to leave the country via the appropriate border crossing points.

Clearly the use of the word ‘immediately’ by Schabowski had superseded the other more significant details in the directive.

- East Germans would be allowed to leave the country but must go through an application process for an authorization that would be issued “in a short period of time”.

- Most importantly, however, was that even though the measures would come into effect immediately once the directive was officially released; that was not supposed to take place immediately but rather the next day- on November 10th

At 7:05pm on November 9th 1989, the Association Press added their own interpretation, spelling out the situation with this sentence:

“According to information supplied by SED Politburo member Günter Schabowski, the GDR is opening its borders.”

By 8pm, the state-financed West German broadcaster ARD had taken this one step further, leading their nightly bulletin with the exact words:

“The GDR is opening its borders.”

Although more succinct, the text was consistent with the government’s intentions. The German Democratic Republic would be opening its border, at some point in future. Even if that was not made entirely clear.

While this growing tide of announcements was being made East Germany’s leadership, including Egon Krenz, was otherwise detained in a Central Committee plenum – that did not finish until 8:47pm.

Less than two hours later, the East German official state news programme Aktuelle Kamera (Topical Camera) made a plea to correct any misunderstanding:

“At the request of many citizens, we inform you once again about the new travel regulations from the ministerial council. First: private trips can be applied for without having to first provide evidence of need to travel or familial relationships. So: Trips are subject to an application process!”

This pace of the media by this point was unstoppable, and the story had already overtaken any bureaucratic concept of reality. At 10:40pm, the West German ARD late-night news show Tagesthemen (Themes of the Day) began with the following announcement:

“This ninth of November is a historic day: the GDR has announced that its borders are open to everyone, with immediate effect, and the gates of the Wall stand wide open.”

ARD had just thrown petrol onto the fire.

Immediately following this announcement, however, the programme went live to the Invalidenstrasse checkpoint in Berlin to illustrate its claim: bizarrely showing that the border at this time still remained firmly closed.

Increasingly, however, for the next 50 minutes, curious East Germans would arrive en masse at seven flashpoint locations across the city.

- Invalidenstraße/Sandkrugbrücke

- Chausseestraße/Reinickendorfer Straße

- Heinrich-Heine-Straße/Prinzenstraße

- Sonnenallee

- Oberbaumbrücke

- Checkpoint Charlie/Friedrichstraße

- Bornholmer Straße/Bösebrücke

At around 11:30pm, the screen fence preventing movement westwards at the Bösebrücke crossing was rolled back by the border guards and the huge crowd that had gathered on the east side of the bridge swarmed into the checkpoint area. Checkpoint commander, Lieutenant-Colonel Harald Jäger had decided to order his men to stop checking passports and fully open the border.

Within moments thousands began pouring through the crossing point – before dawn on November 10th around 20,000 people would head West through this single border crossing alone.

- By midnight, all the remaining border crossings had been forced to open. The guards simply chose to step back and allow the situation to unfold.

- At twenty past midnight, the East German army was placed on a state of heightened alert. Although the night would pass without any further orders arriving.

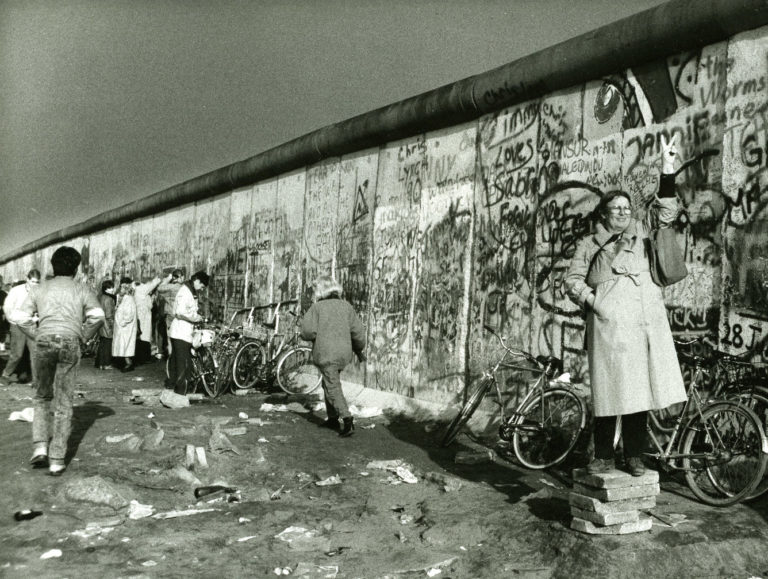

Berlin was now not only an open city but the site of one of the largest street parties the European continent had ever witnessed.

Over the next ten days, over 10 million permits for private travel outside the GDR would be granted by the country’s Interior Ministry and 17,500 applications for permanent emigration approved.

However, it would take almost another year from this point for German reunification to be achieved – with the five East German states being integrated into the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany) – and many further important milestones along the way. Including the dissolution of the East German State Security Police (STASI) on January 13th and the first free and fair parliamentary election in the history of the GDR, held on March 18th 1990. Monetary union on July 1st would see East Germany adopt the Deutschmark, before finally signing a treaty of unification with the West on August 31st 1990.

Years later the term ‘Peaceful Revolution’ (Friedliche Revolution) would be adopted by the German government to refer to the procession of non-violent events that led to the climactic turn of November 9th and the ‘Fall of the Wall’. The path to this point in history had been long and winding – and rather than entirely peaceful, was in-fact littered with the corpses of those who had sought something better, or dreamed of more, and been cast as kindling into the fire.

The construction of the Berlin Wall in 1961 had proven to be a great success for the East German government; it stemmed the flow of refugees flooding into West Berlin – reducing the numbers from thousands per month to around 5,000 escapees over the space of some twenty eight years.

Although, for every second the Wall stood, it was also proof that the East German system had failed utterly; and that the only way the continued existence of the country could be assured was through the exercise of force – and the murder of anyone who attempted to vote with their feet and flee the country’s socialist experiment.

Until that fateful night in November 1989.

When everything finally changed forever.

**

Conclusion

YES

The final nail in the coffin was more accident than intention.

Schabowski’s fumbled press conference had dropped the ball; and the Western media had simply carried it across the line.

Certainly, the East German government – although in crisis – had no intention of resolving its situation by immediately opening the floodgates to West Berlin.

It must, however, be stated that Schabowski’s announcement came at the tail end of a procession of spectacular events – a popular protest movement that certainly was not devoid of purpose and driven by the ordinary people of the countries of Eastern Europe. Some calling for reform; many calling for a form of revolution. Regime change and reunification with the West.

Plausibly, it could be argued that the end of the Wall – signaling as it also did the point-of-no-return for the East German ruling regime – was something of an accident by design. Whether intentional or not, its end was certainly inevitable and with it the whole enterprise of the Soviet system – expanded and entangled since the Bolshevik seizure of power – was destined for the rubbish bin of history.

As the socialist economy proved impossible to maintain in the long run.

And the clay of socialist society refused to take shape.

The ideology of Marx, Engels, and Lenin had been implemented under the misapprehension that where man is not born equal he can be made equal by force. While recognising that the revolution eats its young; this system inevitably struggled to come to terms with how its children might rise to eat the revolution.

***

If you’ve enjoyed reading this article, consider booking one of our private guided tours of Berlin.

Sources

Appelbaum, Anne (2012), Iron Curtain – The Crushing of Eastern Europe 1944-56. ISBN-13 : 978-0385515696

Buber-Neumann, Margarete (2009) Under Two Dictatorships: Prisoner of Stalin and Hitler. ISBN-13 : 978-1845951030

Bruce, Gary (2010), The Firm: The Inside Story of the Stasi. ISBN-13 : 978-0195392050

Carruthers, Susan L. (2009), Cold War Captives: Imprisonment, Escape, and Brainwashing. ISBN-13 : 978-0520257313

Conquest, Robert (1999), Reflections on a Ravaged Century. ISBN-13 : 978-0393048186

Frye, David (2019), Walls: A History of Civilization. ISBN-13 : 978-0571348428

Kempe, Frederick (2011), Berlin 1961. ISBN-13 : 978-0399157295

Kotkin, Stephen (2011), Armageddon Averted: The Soviet Collapse 1970-2000. ISBN-13 : 978-0195368635

Koehler, John O (1999), Stasi: The Untold History of the East German Secret Police. ISBN-13 : 978-0813337449

Lewis Gaddis, John (2007) The Cold War. ISBN-10 : 0141025328

Panorama DDR, 100 Questions, 100 Answers

Revel, Jean Francois (1977) The Totalitarian Temptation. ISBN-13 : 978-0385122740

Rodden, John, The Tragedy of “June 17”: East Germany’s “Workers’ Uprising” at Sixty

The Centre of Contemporary History Potsdam and The Berlin Wall Foundation, The Victims of the Berlin Wall 1961-1989

HISTORICAL ARTICLES

Mythbusting Berlin

Are There Any Nazi Statues Left In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

Visitors to Berlin often arrive expecting to find the physical remnants of the tyranny of the 20th century still standing – statues of dictators, triumphal arches, or bronze idols. Instead, they often find none. The stone symbols and statues of the Third Reich are still gazing down on them, however, hiding in plain sight. But why are there no statues of Hitler? Did the Allies destroy them all in 1945, or is the truth stranger

Could The Western Allies Have Captured Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

To contemplate a Western Allied capture of Berlin in 1945 is to challenge the established endgame of the Second World War. What was the true military and logistical feasibility of a Western Allied assault on the Nazi capital? What factors truly sealed Berlin’s fate, and what might have changed had the Allies pushed eastward?

Answering these questions means delving into the complex interplay of logistics, political maneuvering, and the competing visions for a post-war world

Did Any Of The Rothschild Dynasty Die In The Holocaust? – Mythbusting Berlin

The Rothschild name is synonymous with immense wealth, influence, and persistent conspiracy theories—especially during the era of Nazi Germany. Often targeted by antisemitic propaganda, the family’s survival during World War II has sparked myths about their supposed immunity from Nazi persecution. But did any Rothschild family member actually perish in the Holocaust? This article explores that compelling question, unraveling historical misconceptions and revealing the reality behind one of Europe’s most famous dynasties.

Did Frederick The Great Introduce The Potato To Germany? – Mythbusting Berlin

One of the more bizarre claims to fame attributed to the first King of Prussia is that the man who would go down in history known as Frederick the Great introduced the potato to Germany during his reign back in the 1700s. This starchy root vegetable has undoubtedly become a staple part of German cuisine – an essential addition to any plate of Schnitzel, Schweinshaxn, and Königsberger Klopse – however, whether Frederick the Great is

Did Hitler Escape To Argentina In 1945? – Mythbusting Berlin

Although Nazi leader, Adolf Hitler, certainly remains an inescapable figure, could there be any truth to the story of his escape to Argentina in 1945? That the most wanted man on earth could simply vanish, to spend the rest of his life peacefully in South American obscurity captivates imaginations. Yet, despite numerous investigations, this tale persists primarily as myth—fueled by speculation, hearsay, and conspiracy theories.

Did Hugo Boss Design The Nazi Uniforms? – Mythbusting Berlin

The idea that Hugo Boss – the man whose name now adorns expensive suits and fragrances – was the creative genius behind the Nazi uniforms suggests a terrifying collision of haute couture and holocaust – a marriage of high style and high crimes. The image is striking: a German tailor sketching the ultimate villain’s costume. But history, as usual, is far messier, more bureaucratic, and more banal than the internet memes suggest. To understand who

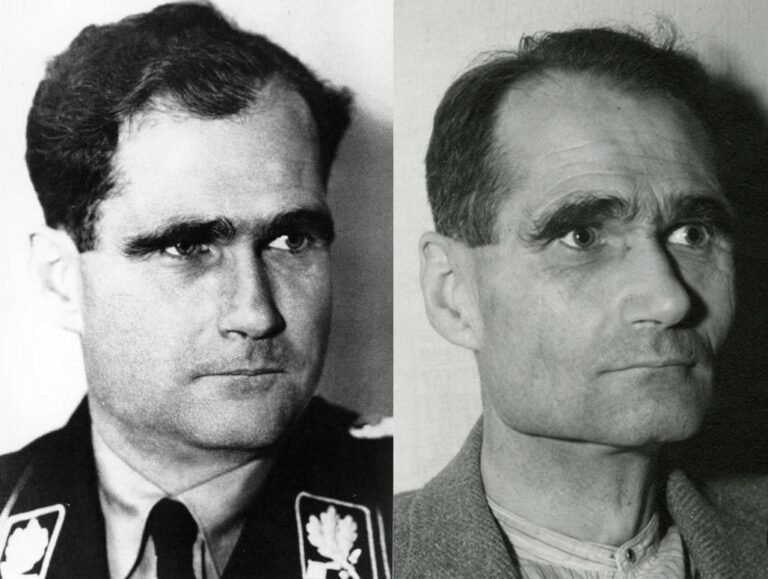

Did Rudolf Hess Really Commit Suicide? – Mythbusting Berlin

On a summer’s day in 1987, the last Nazi war criminal of the Nuremberg trials was found dead in a prison built for hundreds, yet for two decades, housed only him. The official verdict was suicide, a straightforward end to a life defined by fanaticism, delusion, and contradiction.

But the simplicity of the report belied the complexity of the man and the 46 years he had spent in Allied custody. In the meticulously controlled

Did The Nazis Develop Nuclear Weapons? – Mythbusting Berlin

The Nazi obsession with super-weapons became so serious in the closing stages of the Second World that Adolf Hitler personally believed that such ‘Wunderwaffen’ both existed in a usable form – and would save the country from defeat. Had the Nazis managed to develop nuclear weapons by 1945 – the outcome of the war would surely have been different. But how close were Hitler, Himmler, and his henchmen to developing an A-bomb?

Did The Nazis Invent Decaf Coffee? – Mythbusting Berlin

Persistent rumors claim that Nazis preferred their coffee anything but pure, leading some to wonder if they might have influenced the development of decaffeinated coffee. Although decaf was already widely available across Europe by the mid-20th century, speculation continues: could the Nazis really have played a role in popularizing—or even discovering—this caffeine-free alternative, or is this simply another caffeinated conspiracy cooked up to sensationalize an ordinary historical detail?

Did The Nazis Invent The Bicycle Reflector? – Mythbusting Berlin

The fruits of wartime ingenuity are plenty – so many, in-fact, that it has become somewhat of a worn cliche that as the guns start firing the innovators get to work, often solving problems while providing more problems for the enemy to overcome.The kind of progress that results in the production of newer improved, more lethal weapons, such as to increase the chances of victory.

Did The Nazis Run The Largest Counterfeiting Operation In History? – Mythbusting Berlin

During the Second World War the Nazis masterminded an astonishing plot to destabilise Britain by flooding its economy with counterfeit banknotes. Crafted in secret by concentration camp prisoners, this forged fortune became the most ambitious counterfeiting operation ever attempted. But was it history’s largest? Dive into the extraordinary tale of Operation Bernhard,

rife with deception, survival, and intrigue—revealing the truth behind one of the Third Reich’s most audacious schemes and its surprising legacy.

Did The Second World War End In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

When is a war ever truly over? When the last shot is fired in anger would seem like the best measure. Rarely, though, is it possible to gain insight into such a moment.

Remarkably, a record still exists of such a moment at the end of the First World War on the Western Front. A seismic register and recording of the last belching battery of British guns firing artillery across no-man’s-land, followed by a profound

Did The Spanish Flu Pandemic Help The Nazis Take Power? – Mythbusting Berlin

The devastating Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918-1919 struck amid Germany’s post-war turmoil, compounding social instability, economic hardship, and widespread political disillusionment. Could this catastrophic health crisis have indirectly paved the way for Nazi ascension? While often overshadowed by war and revolution, the pandemic’s profound psychological and societal impacts arguably contributed to the perfect storm, enabling extremist ideologies—including Nazism—to gain popularity and ultimately seize power in a fractured Germany.

Have Adolf Hitler’s Remains Been DNA Tested? – Mythbusting Berlin

In the smouldering ruins of Berlin in 1945, the world’s most wanted man vanished. Did Adolf Hitler, as official history attests, die by his own hand in the Führerbunker? Or did he escape, fuelling a thousand conspiracy theories that have echoed for decades? For years, the Soviets claimed to hold the gruesome proof of his death: a skull fragment and a set of teeth, locked away in Moscow archives. But in an age of definitive

How Did The Nazi Concentration Camps Differ From The Soviet GULAG?

The Nazi concentration camps and Soviet Gulag system have often been conflated in popular imagination—twin symbols of twentieth-century totalitarian horror. Yet the two systems operated on fundamentally different principles. One extracted labor to fuel industrialisation while accepting mass death as collateral damage; the other evolved into purpose-built machinery of genocide. Understanding these distinctions isn’t merely academic—it reveals how different ideologies produce different atrocities, and why Germany and Russia reckon with these legacies so differently today.

How Long Did It Take To Build The Berlin Wall? – Mythbusting Berlin

It is one of the most enduring images of the 20th century: a city divided overnight. The popular narrative tells us that Berliners went to sleep in a unified city and woke up in a prison. While the shock of August 13th 1961, was very real, the idea that the ‘Wall’ appeared instantly is a historical illusion. The physical scar that bisected Berlin was not a static creation, but a living, malevolent beast that evolved

How Many Assassination Attempts On Adolf Hitler Were There? – Mythbusting Berlin

Nazi leader, Adolf Hitler, projected an aura of invincibility, a man of destiny shielded by providence. But behind the carefully constructed image of the untouchable Führer lies a story of constant threat, of bombs that failed to detonate, and errant bullets that missed their mark. Unearth the hidden history of the numerous attempts on Hitler’s life as we explore the courage of those who tried to change the course of history and the devil’s luck

How Many Jews Died In The Holocaust? – Mythbusting Berlin

The answer to the question posed of how many Jews died in the Holocaust is a simple one: too many. That merely one death was an unforgivable obscenity is a fundamental and necessary realisation in understanding the capriciousness of this unparalleled racial genocide. To comprehend, however, the full number of Jews murdered in Europe by the Nazi regime in the 1930s and 1940s is a detective story of epic proportions: the evidence overwhelming, multifaceted, and

How Many People Died Trying To Escape East Germany? – Mythbusting Berlin

The image of the Berlin Wall is seared into our collective memory, a concrete symbol of Cold War oppression. We think of the daring escapes and the tragic deaths of those who failed. But that well-known number is only a fraction of the truth. The story of those who died trying to escape East Germany is far broader and more complex than most imagine, stretching along a thousand-kilometer border and out into the cold waters

How Old Is Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

A relatively new arrival in Europe, Berlin is over 1000 years younger than London, nevermind Rome or Athens, Jerusalem or Jericho. Just how old is Berlin though?

A question fraught with false assumptions and distortions – that has more often than not been answered with propaganda as it has with the cold hard truth.

Was Adolf Hitler A Drug Addict? – Mythbusting Berlin

Solving the enigma of the ‘Führer’ has become a preoccupation for many, since the arrival of the Austrian-German onto the world stage – although moving beyond the mythology without falling into the trap of prejudically extrapolating on the psychopathography of Hitler or demonising so as to excuse his actions has proven problematic. What to make of the man who became more than the sum of his masks? The painter; the military dilettante, the mass murderer,

Was Adolf Hitler A Freemason? – Mythbusting Berlin

History abhors a vacuum, but adores a mystery. Such is the speculative fiction suggesting a secret allegiance behind the rise of the Third Reich – that the catastrophe of the Second World War was orchestrated from the shadows of a Masonic lodge. The image of Adolf Hitler—the drifter from Vienna turned dictator—as a covert initiate of the very brotherhood he publicly reviled, however, creates a paradox that collapses under scrutiny. As when we unlock the

Was Adolf Hitler Gay? – Mythbusting Berlin

In the shadowy corridors of Third Reich history, few questions provoke as much tabloid curiosity and scholarly exasperation as the sexuality of Adolf Hitler. For decades, rumors have swirled—whispered by political enemies in 1930s Munich, psychoanalyzed by American spies in the 1940s, and sensationalized by revisionist authors today. Was the dictator who condemned thousands of men to concentration camps for “deviant” behavior hiding a secret of his own? By peeling back the layers of propaganda,

Was Adolf Hitler Jewish? – Mythbusting Berlin

Was the dictator who orchestrated the murder of millions of European Jews secretly one of them? It is perhaps the darkest irony imaginable, a story whispered for decades in backrooms, bars, and conspiracy forums alike. The most-common rumour – the ‘Frankenberger Myth’ – suggests that Adolf Hitler’s paternal grandfather was Jewish, a secret so damaging it could have unraveled the entire Nazi regime. But where does this claim come from? And, more importantly, is there

Was Currywurst Invented In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

Explore the story behind what many consider Berlin’s most iconic snack—the ever-so-humble Currywurst. Often hailed as an enduring symbol of culinary creativity amid Cold War scarcity, this humble dish has inspired fierce debate about its true origin. But was it genuinely invented here in Berlin, or have proud locals simply adopted and elevated this spicy street-food favorite into legendary status all their own?

Was Fanta Invented By The Nazis? – Mythbusting Berlin

As one of the most secretive organisations in the world, the Coca Cola corporation refuses to share its secret recipe with anyone. Famously insisting only on shipping the base syrup of its drinks to plants around the world to be carbonated and distributed.

This combined with the trade limitations of the Second World War may have led to the introduction of one of the most popular soft-drinks in the world. But could it be true:

Was Frederick The Great Gay? – Mythbusting Berlin

Frederick II of Prussia, better known as Frederick the Great, is often remembered as the archetypal enlightened monarch – a brilliant military commander, patron of the arts, and learned philosopher. Yet behind the stern portraits of this 18th-century warrior-king lies a personal life long shrouded in intrigue and speculation. Intrigue around the king’s sexual orientation has persisted through the centuries, chiefly revolving around one question: Was Frederick the Great gay?

Was Henry Ford A Nazi? – Mythbusting Berlin

US auto tycoon, Henry Ford, holds the ignominious distinction of being the only American Adolf Hitler praised by name in his National Socialist manifesto: ‘Mein Kampf’. This was not, as it turns out, the only connection between Ford and the Party of Hitler, Himmler, and the Holocaust.

Ford’s overt affinity with the Third Reich reveals a troubling past. How deep these connections ran, and how consequential they were for both sides, is a chapter

Was The Colour Blue Invented In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

Tracing the true history of blue—from ancient Egyptian dyes to the accidental discovery of Prussian Blue in a Berlin lab. We’ll debunk myths about seeing blue, explore colonial indigo plantations, scale mountains with a cyanometer, and trace Van Gogh’s starry skies—all to answer one question: how did Berlin shape our understanding of the world’s rarest color?

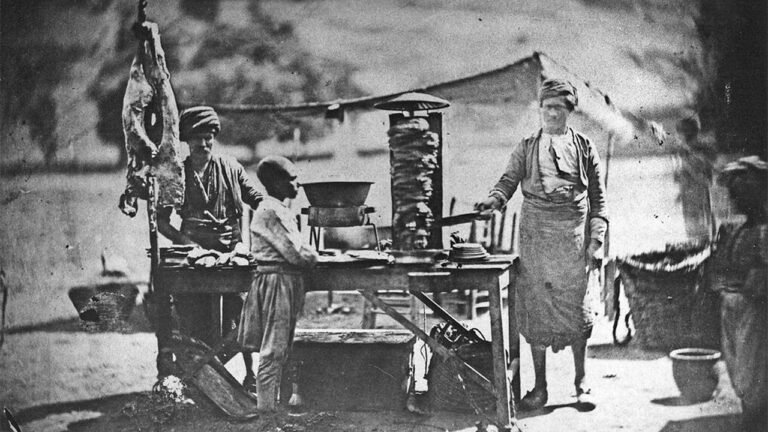

Was The Döner Kebab Invented In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

Unlikely icon of immigrant success; fast food symbol of the working class; over-hyped midnight disco eat; or culturally appropriated cuisine? Its influence goes far beyond layers of seasoned meat and fresh vegetables stuffed into pita bread. But does Berlin deserve credit as the Döner Kebab’s true birthplace, or has the city merely refined and popularized a culinary tradition imported from elsewhere?

Was The Fall Of The Berlin Wall An Accident? – Mythbusting Berlin

On a seasonally crisp night in November 1989, one of the most astonishing events of the 20th century occurred. After twenty eight years, three months, and twenty eight days of defining and dividing the German capital, the Berlin Wall ceased to exist – at least in an abstract sense. Although the removal of this symbol of the failure of the East German system would take some time, its purpose – as a border fortification erected

Was The Nazi Party Democratically Elected? – Mythbusting Berlin

The myth persists that Adolf Hitler rose to power through popular democratic choice. Yet history reveals a darker, more complicated truth. Hitler’s ascent involved exploiting democratic institutions, orchestrating violence, propaganda, and political intrigue—not a simple election victory. Understanding how Germany’s democracy collapsed into dictatorship helps illuminate the dangerous interplay between public desperation, elite miscalculations, and extremist ambition, providing crucial lessons for safeguarding democracy today.

Were The Allied Bombings Of Germany War Crimes? – Mythbusting Berlin

The history of the Allied bombing of Germany during the Second World War still triggers fierce debate. Was reducing cities to rubble a necessary evil – justice from above in a just war – or an unforgivable crime? Can the intentional targeting of civilians ever be justified as militarily necessary?

In a conflict where all rules seemed to vanish, an even more pertinent question persists: by the very standards they would use to judge their

Were The Nazi Medical Experiments Useful? – Mythbusting Berlin

Before the Nazi period, German medicine was considered the envy of the world – a shining monument to progress. But deep within that monument, a rot was spreading, one which would collapse the entire structure into an abattoir. From the wreckage, we are left with a profoundly uncomfortable inheritance: a moral enigma wrapped in doctor’s whites.

What to make of the data, the images, and the terrible knowledge gleaned from unimaginable human suffering. Whether

What Are The Origins Of The Nazi Salute? – Mythbusting Berlin

A specter is haunting the modern mind, a gesture so charged with the dark electricity of history that its mere depiction can unleash a storm of controversy.

It is a simple movement: the right arm, stiff and straight, raised to the sky. But in that simplicity lies a terrifying power, a symbol of a regime that plunged the world into an abyss and a chilling reminder of humanity’s capacity for organised hatred.

This

What Are The Origins Of The Nazi Swastika? – Mythbusting Berlin

Long before the legions of the Third Reich marched beneath its stark, unnerving geometry, the swastika lived a thousand different lives. It was a symbol of breathtaking antiquity, a globetrotting emblem of hope and good fortune that found a home in the most disparate of cultures. To even begin to understand its dark 20th-century incarnation, one must first journey back, not centuries, but millennia.

What Are The Pink Pipes In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

A first-time visitor to Berlin could be forgiven for thinking the city is in the midst of a bizarre art installation. Bright pink pipes, thick as an elephant’s leg, climb out of the ground, snake over pavements, arch across roads, and disappear back into the earth. Are they part of a complex gas network? A postmodern artistic statement? A whimsical navigation system? These theories, all logical, are all wrong. The truth is far more elemental,

What Do The Colours Of The German Flag Symbolise? – Mythbusting Berlin

What does a flag mean? Is it merely a coloured cloth, or does it hold the hopes, struggles, and identity of a nation? The German flag, with its bold stripes of black, red, and gold, is instantly recognisable. But the story of its colours is a tumultuous journey through revolution, suppression, and reinvention. The common explanation for their symbolism is a simple, romantic verse, yet the truth is a far more complex and contested tale,

What Happened To Adolf Hitler’s Alligator? – Mythbusting Berlin

It is often said that you can tell a lot about a person by their relationship with animals; that owners often come to look and behave like their pets. Or is it perhaps more that people choose their pets to correspond to their personality? Nazi leader Adolf Hitler’s love of dogs, for example, is well documented but what is there to make of his relationship with reptiles?

What Happenened To The German Royal Family? – Mythbusting Berlin

When the smoke cleared over the trenches in November 1918, the German Empire had evaporated, and with it, the divine right of the Hohenzollern dynasty. Conventional wisdom suggests the family simply vanished into the sepia-toned obscurity of history books—exiled, forgotten, and irrelevant. But dynasties, like weeds in a landscaped garden, are notoriously difficult to uproot entirely. The story of the German royals did not end with the Kaiser’s flight to Holland; it merely shifted gears.

What Is The Difference Between Fascism & Nazism? – Mythbusting Berlin

While the terms ‘Fascist’ and ‘Nazi’ are often bandied around interchangeably as shorthand for tyranny – Italian fascism and German National Socialism were distinctly different beasts. Albeit ideological kin. One an ideology of state-worship, born from post-war chaos and national pride; the other built upon a fanatical, pseudo-scientific obsession with race. Two peas in the same totalitarian pod – twins in tyranny – more succinctly summarised as the Nazi chicken to the Fascist egg.

What Was Checkpoint Charlie? – Mythbusting Berlin

Checkpoint Charlie remains among Berlin’s most visited historical sites, famed worldwide for its significance during the Cold War. Originally established as a modest border-crossing point, it evolved dramatically over the decades into an international symbol of freedom, espionage, and intrigue. Today, critics and locals often dismiss it as little more than a tourist trap—Berlin’s Disneyland—but how exactly did Checkpoint Charlie get its peculiar name, and what truths hide behind its popularity?

What Was Prussia? – Mythbusting Berlin

Prussia’s legacy is both remarkable and contentious—once a minor duchy, it rose dramatically to shape modern European history. Renowned for military discipline, administrative efficiency, and cultural sophistication, Prussia was instrumental in uniting the German states, laying foundations for a unified Germany. But how did this kingdom, with its roots in Baltic territories, achieve such prominence, and why does its complex history continue to evoke admiration, debate, and occasional discomfort in Germany today?

What Was The Berlin Airlift? – Mythbusting Berlin

In the ruins of 1948, the silence of Berlin was not a sign of peace, but a held breath before a new catastrophe. The city, drowning in rubble and political intrigue, became the staging ground for the twentieth century’s most audacious gamble. While popular history remembers the chocolate parachutes and smiling pilots, the reality of the Berlin Airlift was a terrifying operational nightmare born from a ruthless currency war. It wasn’t just a humanitarian mission;

What Was The Socialist Kiss? – Mythbusting Berlin

It is one of the most curious and enduring images of the Cold War: two middle-aged, grey-suited men, locked in a fervent embrace, their lips pressed together in a kiss of apparent revolutionary passion. This was the ‘Socialist Fraternal Kiss’, a ritual that, for a time, seemed to encapsulate the unwavering solidarity of the Eastern Bloc.

But what was behind this seemingly intimate gesture? Was it a genuine expression of camaraderie, a piece of

Who Built The Berlin Wall? – Mythbusting Berlin

One of the most common questions I have encountered from people curious about Berlin, and often so cryptically phrased. Who built the Berlin Wall? A simple five-word query, yet one that can be read one of two ways. More than thirty years since the ‘Fall of the Wall’, the story of its construction continues to baffle many who are mainly familiar with its existence through knowledge of its importance…

Who Really Raised The Soviet Flag On The Reichstag? – Mythbusting Berlin

One iconic photograph has come to symbolise the Red Army’s victory over Nazi Germany in 1945—the Soviet flag waving triumphantly above Berlin’s battered Reichstag building. Yet behind this enduring image lies controversy, confusion, and political manipulation. Who truly raised the Soviet banner atop the Reichstag? Was it a spontaneous act of heroism or carefully staged Soviet propaganda? Decades later, unraveling the truth reveals surprising layers beneath the mythologized symbol of Soviet triumph.

Who Was Really Responsible For The Reichstag Fire? – Mythbusting Berlin

Various theories have been posited as to who actually set fire to the German parliament in 1933. Was it the opening act in an attempted Communist coup or a calculated false flag operation carried out by elements of the Nazi Party, intended to create the conditions necessary for introducing single-party rule? And what part did the young man from Holland, arrested shirtless inside the building the night of the fire, play in this event?

Who Were The Last Nazis On Trial? – Mythbusting Berlin

More than eighty years after the Holocaust, courtrooms across Germany still echo with testimony from the final chapter of Nazi justice. Centenarian defendants in wheelchairs, their faces hidden behind folders, arrive to answer for crimes committed in their youth. These are not the architects of genocide—those men faced their reckoning at Nuremberg decades ago. These are the guards, the secretaries, the bookkeepers: ordinary people who enabled extraordinary evil. Their trials represent a legal revolution: the

Why Is Berlin The Capital Of Germany? – Mythbusting Berlin

There was little in its humble origins—as a twin trading outpost on a minor European river—to suggest that Berlin was destined for greatness. It sits on the flat expanse of the North European Plain, a landscape once dismissively referred to as the “sandbox of the Holy Roman Empire.” Unlike other world capitals, it lacks breathtaking scenery or a naturally defensible position. It is a city built not on majestic hills or a grand harbour, but