“The repeated claim before the ‘seizure of power’ – that the NSDAP, as a national social-revolutionary movement, and not simply another political party… would create new bonds of unity through its elimination and transcending of the party system, was highly attractive and conveyed much of Nazism’s dynamic appeal.”

Ian Kershaw, author of The “Hitler Myth”: Image and Reality in the Third Reich

In seeking to understand the world we often fall prey to the desire to simplify it.

To make it black and white – like water and oil – and cast judgement on how best to tell the difference. Nowhere is that more self-evident than in how we view the past.

Without a doubt, on the scoreboard of villainy, Nazi Germany ranks highly – as one of the most dreadful regimes in human memory. Even the terminology of its era has been transformed into a collection of bywords for evil. The black and white are distinct and the water and oil inseparable.

Almost a century later, it is still widely assumed that there is no greater social – or political – death than to be branded a ‘Nazi’ or ‘like Hitler’.

But who were these people that enabled this great evil to triumph?

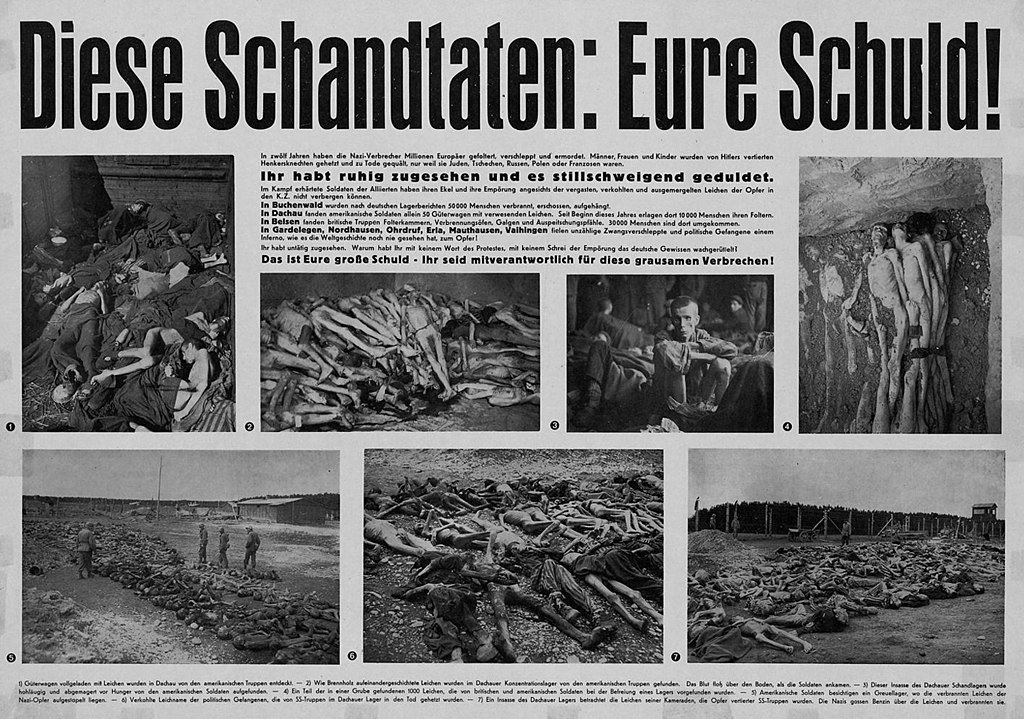

For some time following the end of the Second World War it remained en-vogue to inscribe upon the German population a sense of collective responsibility. The interchangeability of the terms ‘German’ and ‘Nazi’ an affirmation of the continued need for vigilance against the Teutonic spirit – lest it once again thrust the world into war. The story of Nazism, like the bywords it has gifted us, constantly referenced as the ultimate warning from history. That which facilitated what should ‘Never Again’ happen.

To understand how the Nazi Party came to power – and comprehend the swamp from which the monster rose – we must confront one of the major contradictions to have come out of the Second World War.

Nazism in its essence was wrong, as it swiftly condemned whole groups of people based not on their actions but on their ethnicity, their religion, and identity – based on attributes and parts of their individual being that were out of a person’s control in deciding.

A jew should be dealt with as a jew; as a homosexual, as a Slav, or a gypsy should be dealt with for their inescapable identity.

That the German people should be dealt with as a collective body of individuals who enabled the Nazi takeover is to simply conclude that in that German-ness lies the answer to the conundrum of why, how, and for what purpose the Nazi Party managed to take control of one of the largest, most industrious, and seemingly most tolerant countries in the world in 1933.

But in breaking down that story into the water and oil of this simplification, what is lost?

In seeking to simplify this history do we inevitably risk reaching for a reassuring lie rather than the disturbing reality.

Millions of Germans certainly voted for the Nazi Party in its rise to power – but enough to say it was democratically elected? Were those people all ‘Nazis’ and ‘just like Hitler’?

In projecting on the German population a sense of collective guilt and responsibility, are we not missing out on one of the greater lessons of the period?

That – unless arrested at the outset – it can happen here too.

Wherever here is – and whenever is now.

The Glass Republic - The Stillbirth Of German Democracy

“Logic, order, truth, reason, we consign them all to the oblivion of death,” said one Surrealist manifesto. We must “cultivate the hatred of intelligence,” said the leader of the Futurists, Filippo Marinetti, an artist hailed by Mussolini as the John the Baptist of Fascism.”

Leonard Peikoff, author of The Cause of Hitler’s Germany

Democracy in Germany was born late – amid turmoil and betrayal – or so it seemed to many Germans at the time.

In November 1918, as the First World War ground to its bitter end, the German Kaiser abdicated and fled to Holland. In response to this momentous shift in the fabric of society, two competing republics were declared in Berlin.

The first at the Reichstag building by Philipp Scheidemann of the Majority Social Democratic Party of Germany (MSPD), and the second a few hours later by Karl Liebknecht, the leader of the Marxist Spartacus League, at the Berlin Palace.

The so-called German Revolution of 1918-19, also known as the November Revolution, would see these two parties on the left side of the political spectrum jostle for power in the vacuum left by not only the abolition of the monarchy but the departure of all royal heads of the German states.

The more moderate MSPD would take centre–stage in organising the new German Republic in the aftermath of the First World War – having also been directly responsible for the armistice that brought an end to that conflict.

The government was now in the hands of the Council of People’s Representatives, formed on November 10th 1918 by the MSPD, and the Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany (USPD).

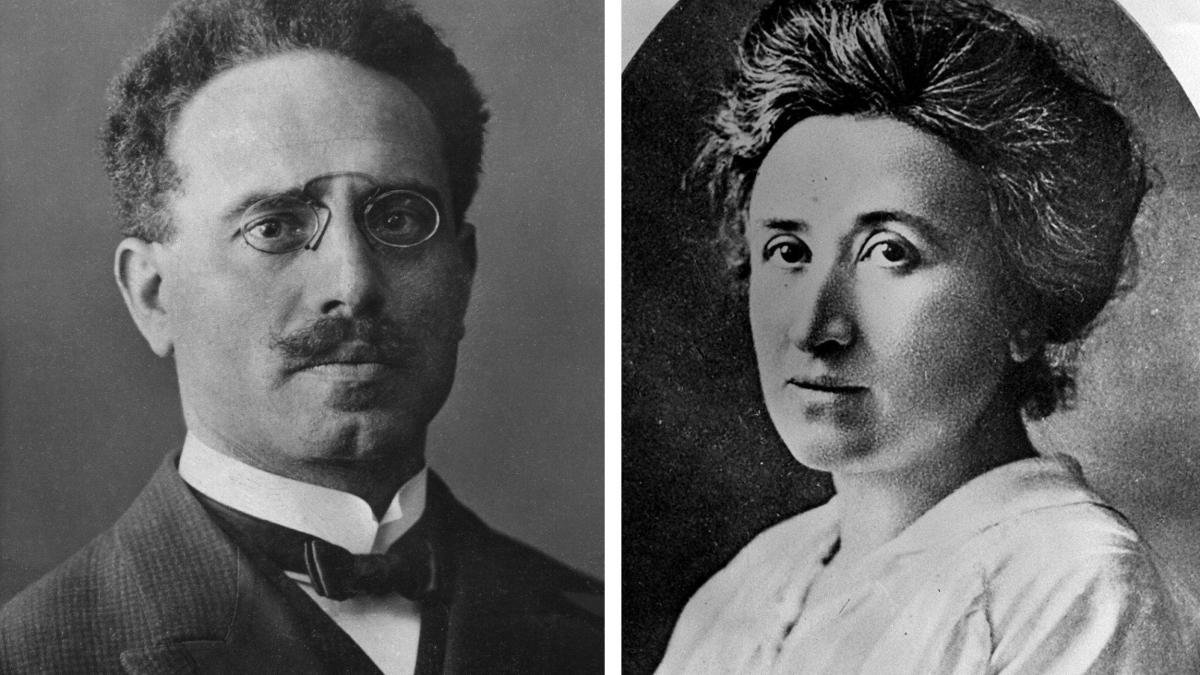

The far Left Spartacists would go on to found the Communist Party of Germany on January 1st 1919 – only to see the two party leaders, Karl Leibknecht and Rosa Luxemburg, murdered by right wing paramilitaries exactly two weeks later.

This joint assassination was officially condemned by the MSPD leadership, which also denied direct involvement. But the murders deepened the split within the socialist movement and left lasting resentment against the MSPD from communist and radical socialist groups.

The repeated reliance upon the right-wing Freikorps militias by the MSPD to suppress more extreme voices calling for a red revolution and dictatorship of the working class – including possibly ordering the deaths of Liebknecht and Luxemburg – led to the coinage of a still-persistent phrase: “Die haben uns verraten, die Sozialdemocraten!” (They betrayed us, the Social Democrats).

Short-lived local soviet republics, similar to the kind that Liebknecht and Luxemburg sought to introduce in Berlin, were also put down in Bavaria (Munich), Bremen and Würzburg with considerable loss of life.

The new Weimar Republic, as Germany’s fledgling democracy came to be known, immediately faced wrath from both ends of the political spectrum.

To the communists and radical leftists, the formation of a republican and parliamentary system with elections to a National Assembly was a half-measure; they wanted a proletarian revolution like the one that had just established Bolshevik rule in Russia.

To hardline nationalists – including the Freikorps paramilitaries the MSPD worked directly with – the republic was illegitimate – “the work of a cabal of Jews and socialists,” they sneered, who had stabbed the nation in the back by surrendering in war.

The ‘November Criminals’ responsible for the humiliating end of the First World War for Germany would never be forgiven – nor forgotten.

In these early years, the moderate democratic government was besieged by foes claiming they could do better – military coups from the right, worker uprisings from the left. It was as if Germany’s newborn democracy was being circled by gravediggers, each eager to bury it for their own cause.

The Gravediggers Of Democracy – A History Of The Nazi Party

“In Hitler, every German should have seen his own shadow, his own worst danger. It is everybody’s allotted fate to become conscious of and learn to deal with this shadow. But how could the Germans be expected to understand this, when nobody in the world can understand such a simple truth?”

Carl Jung, German psychotherapist author of ‘Civilization in Transition’

It was in this toxic brew of anger, disillusionment, and violence that the Nazi Party was born.

In 1919, a diminutive political group calling itself the German Workers’ Party appeared in Munich, one of dozens of extremist factions railing against the Versailles Treaty and the economic hardship that followed the war.

Soon, an Austrian First World War veteran named Adolf Hitler joined its ranks.

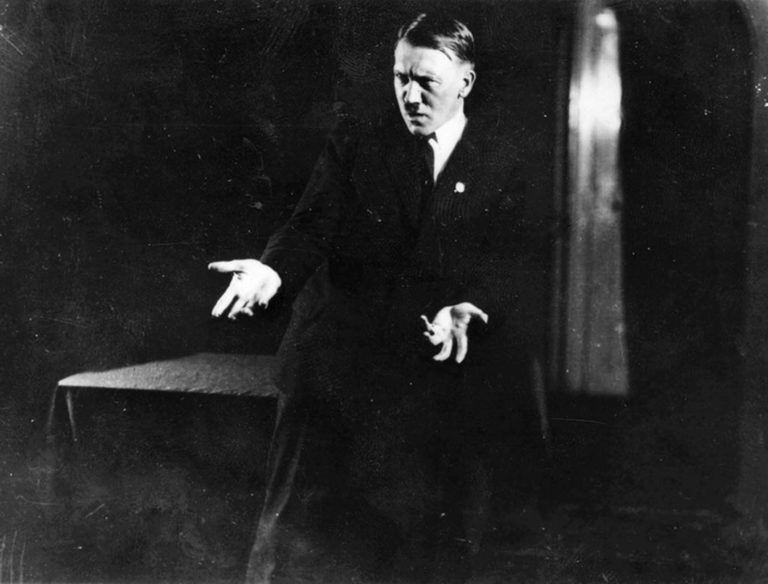

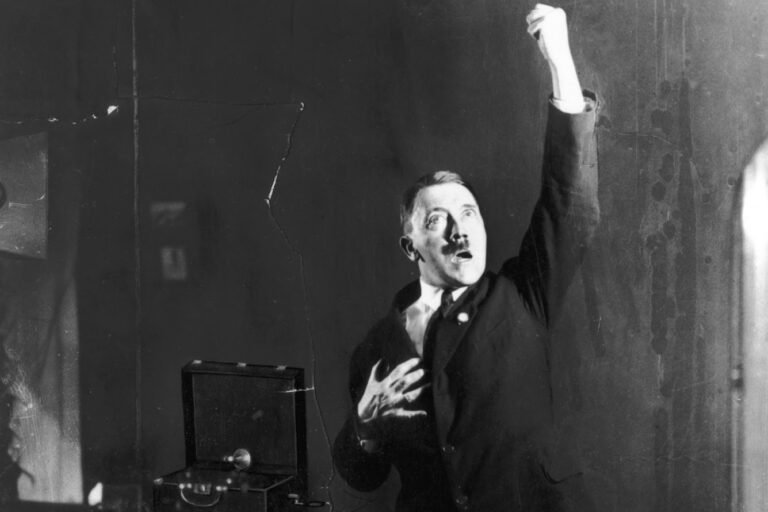

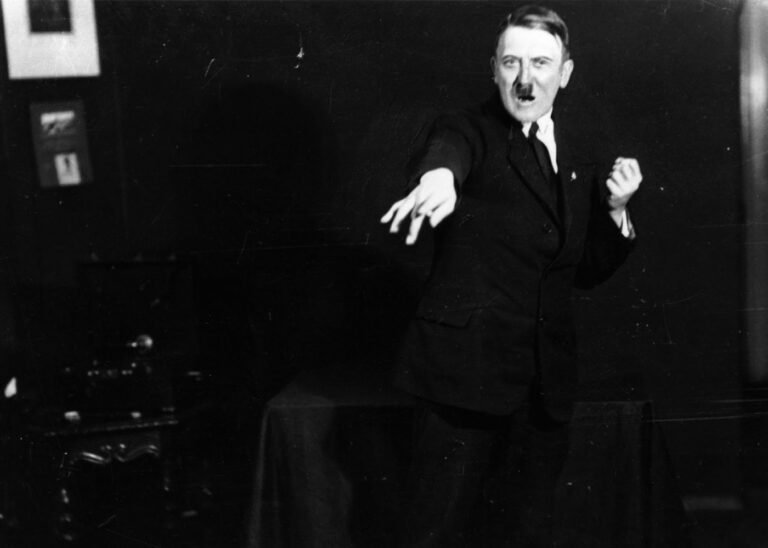

Hitler was a nobody at this point – a failed artist living in men’s hostels – but he discovered in himself a fiery gift for public speaking and a talent for tapping into the resentments of his audience. By 1920, he had maneuvered to the head of the little group and renamed it the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (NSDAP) – the Nazi Party for short.

The name was deliberately paradoxical, blending nationalism and socialism, appealing to both nationalist pride and social discontent.

In practice, the party’s ideology was fiercely right-wing and völkisch (folkish): built on rabid anti-Semitism, anti-communism, and the conviction that Germany must be reborn as a proud, strong, ethnically pure nation.

Democracy did not figure in the Nazi worldview except as an obstacle to be removed.

The Nazi Party’s platform from the start rejected the legitimacy of the Weimar “system.” As one observer later noted, many of the extreme ideas the Nazis trumpeted were not entirely new; they were amplified versions of prejudices and notions already present in German society. Far from being an alien imposition, Nazism drew on what people “had always believed in or taken for granted” – militant nationalism, the glorification of strength, disdain for liberal cosmopolitanism – only now distilled into a pure, intoxicating brew of fanaticism.

In those early years, Hitler and his followers were a fringe curiosity – noisy beer-hall agitators in the political backwaters of Bavaria. But they had outsized ambitions.

They organized paramilitary squads (the Stormtroopers or SA, in their brown uniforms) to brawl with leftist militias in the streets, showing a flair for political violence.

Hitler’s oratory began attracting growing crowds, drawn by his vehement denouncements of the Versailles Treaty (which he called an eternal injustice), of the ‘November criminals’ (the politicians who signed the First World War armistice), of Jews, Marxists, and all those he deemed enemies of the German people.

He had a theatrical style – rants punctuated by shrieks and dramatic pauses – that some found comical or vulgar, but others found mesmerizing. The Swiss psychologist Carl Jung, watching Hitler’s rise, remarked that there was something almost supernatural in the man’s ability to channel the emotions of the crowd.

Hitler, Jung said, was less an individual personality than a vessel for the German collective unconscious – “a medicine man, a spiritual vessel, a demi-deity or, even better, a myth.”

Many educated Germans at the time dismissed Hitler as a vulgar demagogue, “a vulgar little corporal” not to be taken seriously. Yet to his growing band of followers, he spoke with an authority that transcended normal politics. Nazi propaganda cultivated the image of Hitler as a Führer (leader) figure destined to resurrect Germany.

As historian Ian Kershaw observed, part of the Nazi Party’s dynamic appeal was its claim to be more than just another party: it presented itself as a national movement that would transcend and eliminate the squabbling party politics of Weimar. In other words, Hitler offered unity in place of division, strength in place of weakness – a new political religion for those who had lost faith in democracy. This message had magnetism, especially among those who felt betrayed by the existing system.

By 1923, the Nazis felt bold enough to attempt an outright seizure of power. Inspired by Benito Mussolini’s recent ‘March on Rome’ (which had catapulted the Italian fascist leader into the premiership), Hitler and the Nazis, alongside other right-wing groups, staged the Beer Hall Putsch in Munich in November 1923.

The plan was to overthrow the Bavarian government and ignite a national uprising against Berlin. It ended in farce – the putsch was easily crushed by local police, and Hitler landed in prison for treason. But even in failure, the Nazis learned a lesson. Hitler used his trial as a publicity stage, proclaiming his nationalist mission and gaining notoriety beyond Bavaria.

In Landsberg prison, a comfortable facility where he served a mere nine-month sentence, Hitler dictated Mein Kampf (“My Struggle”), a rambling manifesto that laid out his worldview and political strategy. Aside from venomous racism and visions of conquest, Mein Kampf emphasized a new tactic: the “path of legality.”

Hitler concluded that armed revolution was premature; instead, the Nazi Party would need to acquire power through the democratic process – by winning votes, entering government legally, and then subverting the system from within.

In effect, he planned to use democracy’s tools to dismantle democracy.

“We must hold our noses and enter the Reichstag (Parliament),” he told followers, “to procure for ourselves the weapons of democracy. We’ll play their game, get the power legally, and then wreck it!”

This cynical strategy would prove chillingly effective.

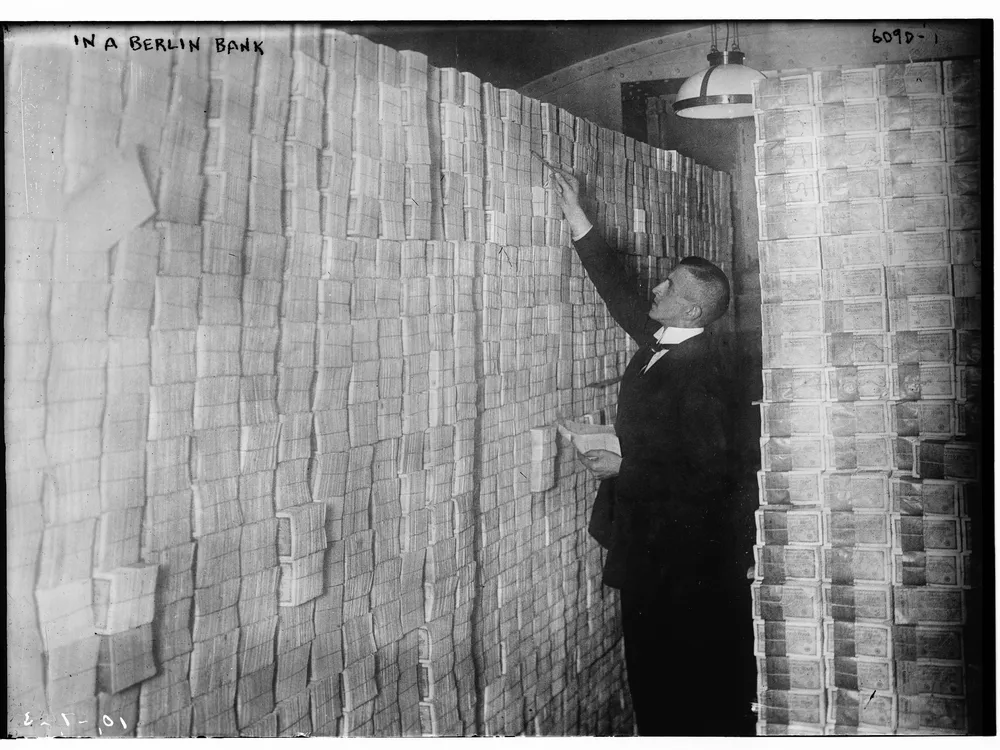

During the mid-1920s, however, Hitler’s grand plans had to wait. Germany entered a period of relative stabilization.

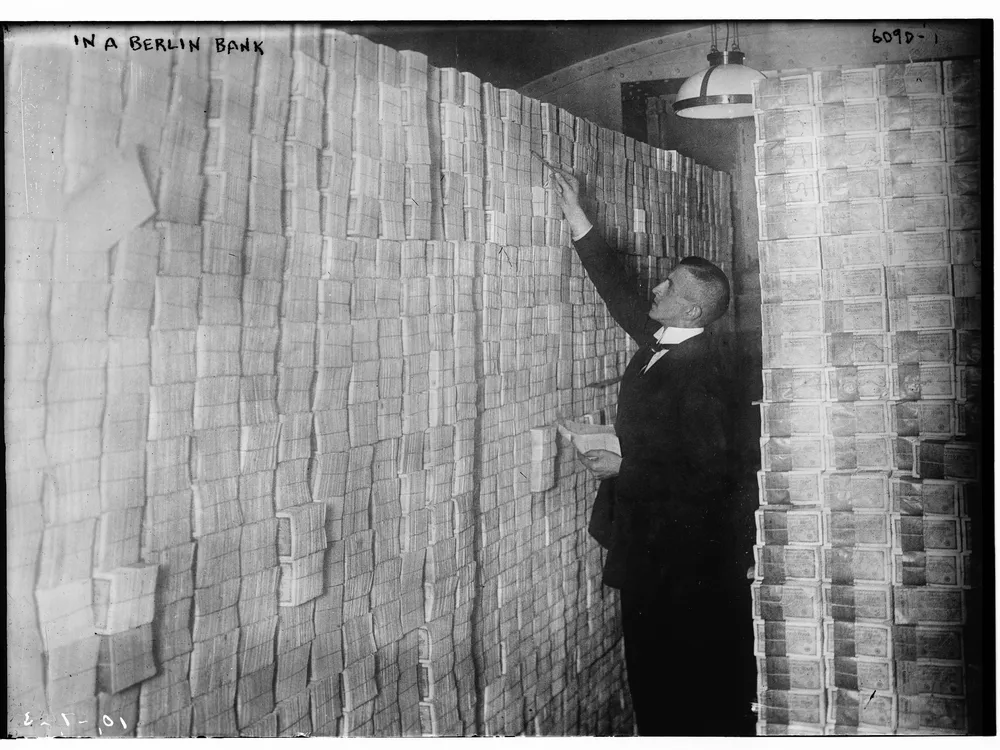

Under foreign minister Gustav Stresemann’s leadership, the hyperinflation of 1923 was brought under control and the economy improved with foreign loans and investment. To many Germans, it seemed the Weimar Republic was finally delivering some normalcy and prosperity.

In the 1928 elections, the Nazis received a pitiful 2.6% of the national vote – a fringe party of cranks on the far right, dwarfed by larger moderate parties and the mainstream Social Democrats. Hitler’s fiery rallies were still drawing mostly the disaffected and fanatical; the average German voter was more concerned with jobs and the price of bread than with Mein Kampf’s grand visions of Aryan destiny.

If this trend had continued, the Nazi Party might have faded away, consigned to the footnotes of history as an extremist curiosity. But fate – or as Kershaw would put it, “the luck of the devil” – intervened on Hitler’s behalf.

The world was about to plunge into economic crisis, and with it German democracy would face its toughest trial.

The Nazi Party’s Path to Power

“The masses have never thirsted after truth. They turn aside from evidence that is not to their taste, preferring to deify error, if error seduce them. Whoever can supply them with illusions is easily their master; whoever attempts to destroy their illusions is always their victim.”

Gustav Le Bon, author of The Crowd – A Study of The Popular Mind

The stock market crash of October 1929 in New York set off a global economic depression, and no nation was hit harder than Germany.

Within a few years, German banks had collapsed, businesses failed in droves, and millions were unemployed. The streets filled with breadlines and beggars; despair and fear permeated daily life. This economic catastrophe was the death knell for public confidence in the Weimar government.

The coalition of democratic parties in power in 1929 fell apart amid disputes over how to respond to the crisis.

The cold calculated capitalism of stocks and speculation seemed to many to have led straight to the gutter. No longer could bold speculation pay. The crash also highlighted the violation of the Christian work ethic – where reward was offered without effort.

Instead, Germany’s future – like when facing Napoleon’s armies, or in the trenches of the First World War – would have to be decided by great sacrifice, and with the strength of leadership the infant Republic now lacked.

Into this breach stepped President Paul von Hindenburg, the venerable World War I field marshal now in his 80s, who began using his emergency powers under Article 48 of the Weimar Constitution to govern by decree.

What that meant, in practice, was that the normal parliamentary process was being sidelined.

Successive chancellors – men like Heinrich Brüning, then Franz von Papen – relied on Hindenburg’s presidential decrees to push through measures (like brutal budget cuts and austerity policies) that lacked majority support in the Reichstag.

With each such step, democratic norms eroded.

The political center was not holding.

Extremist parties on both the left and right surged as people looked for radical solutions.

Here we see what might be called the “snowplow effect”: the political center was essentially plowed off the road, shoved aside into irrelevance, while the extremes gained traction on either side.

The Communists (the far-left KPD) promised a workers’ revolution and gained support among the unemployed and desperate industrial laborers. The Nazis, posing as the saviors of the nation, gained even more.

After years of languishing in obscurity, Hitler’s party suddenly found a mass audience for its message. Nazi organizers and propagandists expertly exploited the climate of crisis. They harped on old resentments (the Versailles Treaty, the supposed “betrayal” of 1918) and scapegoated minorities (Jews above all, but also Communists, Weimar “traitors,” etc.) for Germany’s woes.

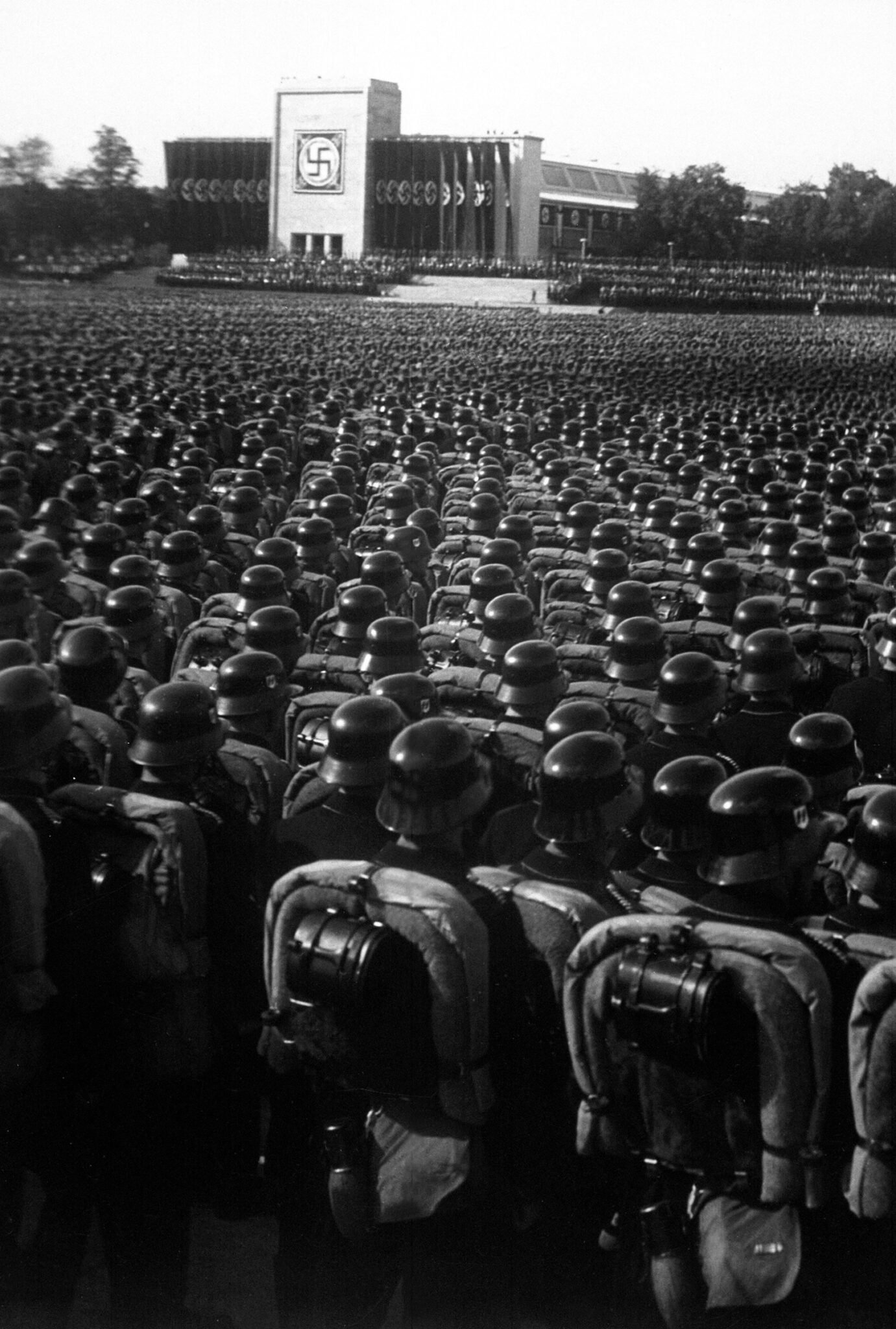

They offered simple, dramatic solutions: throw out the corrupt old politicians, reject the shackles of foreign-imposed treaties, rebuild the economy through massive public works and rearmament, and restore German pride and unity. Hitler crisscrossed the country by airplane (totalling more than 40,000 air miles – equivalent to circumnavigating the globe) in 1932, addressing multiple mass rallies in a single day, projecting energy and ubiquity. Joseph Goebbels, the Nazi propaganda chief, flooded towns with posters of Hitler’s piercing eyes and slogans like “Our Last Hope: Hitler”. The Nazis tailored their appeals to every segment of society – promising jobs and bread to workers, stability and an end to communism for the middle classes, and restoration of national glory for the conservatives.

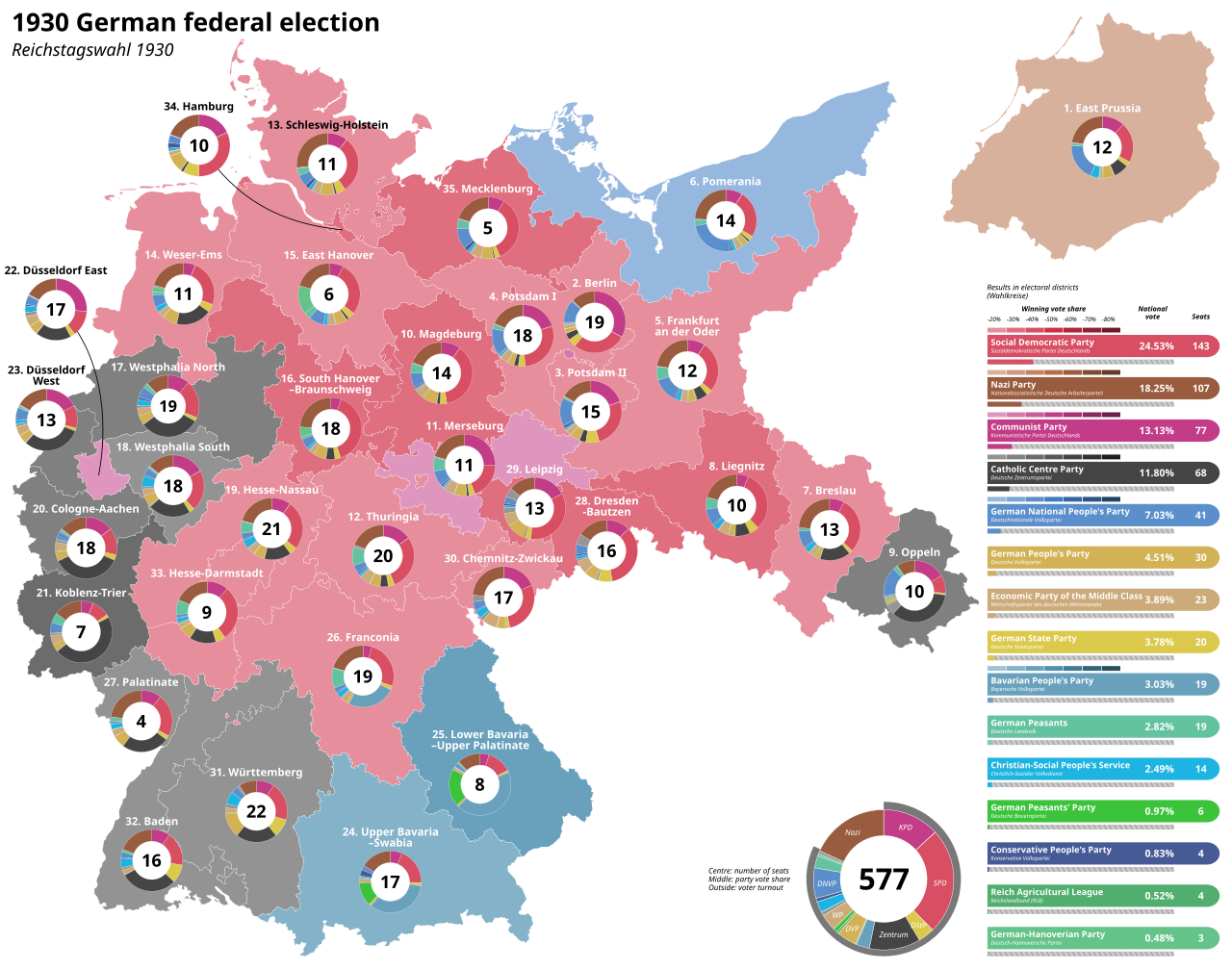

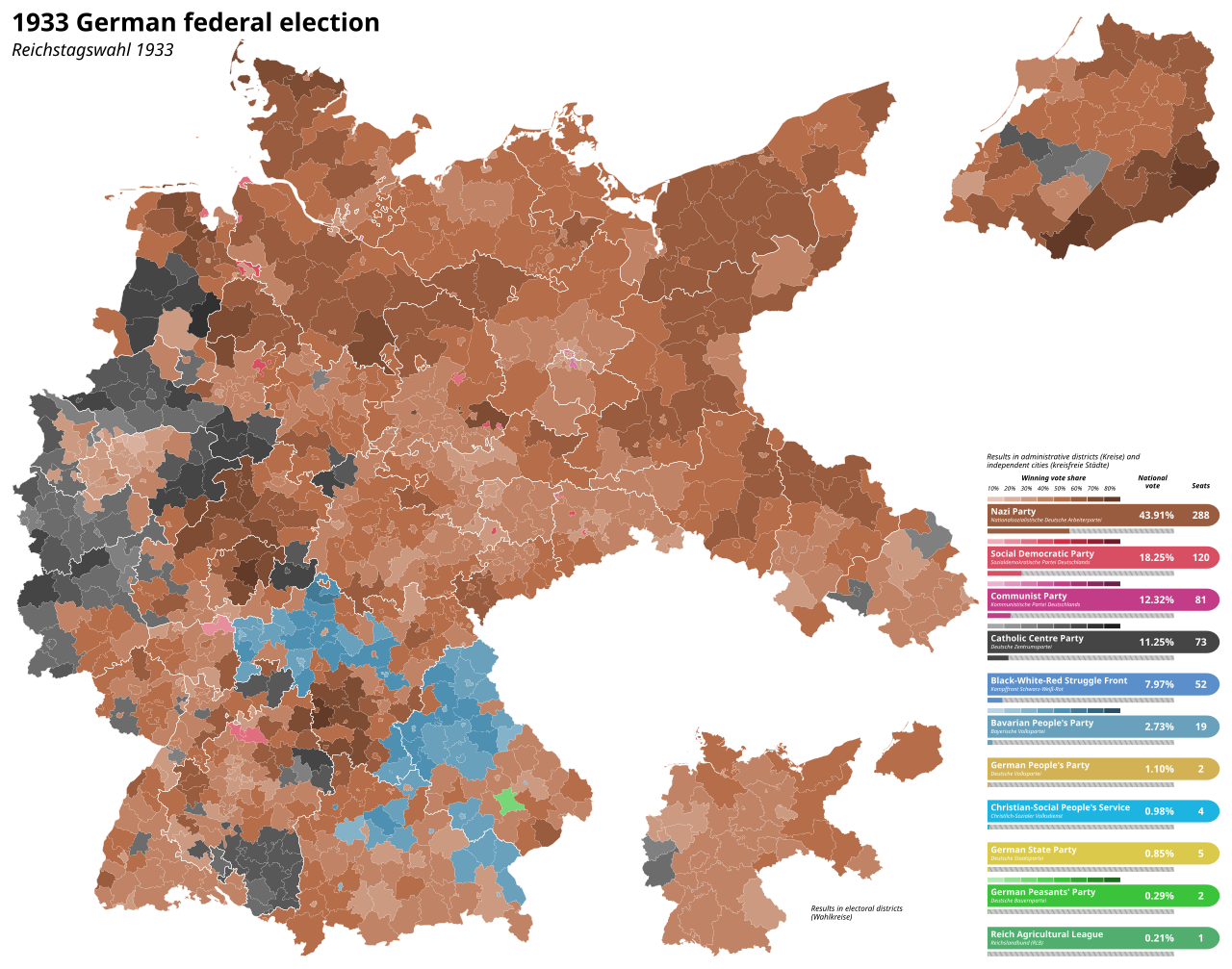

In the 1930 Reichstag election, the Nazi Party astonished the nation by leaping to 18.25% of the vote (over 6 million votes), a stunning increase from 1928. They went from 12 seats to 107 seats in parliament almost overnight. It was the first big jolt that Germany’s democracy was in serious trouble.

Still, 18.25% is far from a majority – the Nazis were powerful, but not yet dominant.

The next two years saw Germany’s situation go from bad to worse.

By 1932, unemployment had spiraled above 30%. The streets in German cities were increasingly overrun by violent clashes – Nazi SA brownshirts and Communist Red Front fighters brawling, turning political disagreements into pitched battles. The weak democratic government seemed paralyzed, unable to maintain order or revive the economy. Voters continued to drift to the extremes, abandoning the traditional moderate parties. In this atmosphere of crisis and polarization, Hitler’s message grew more appealing to many – even to those who found aspects of Nazism distasteful, the Nazi Party now appeared to be a force that might stop the spread of communism or break the deadlock of ineffective governance.

Voters who once supported centrist liberal or conservative parties were now flocking to either the far-right Nazis or the far-left Communists, leaving the moderate politicians withering and the Reichstag fragmented into hostile camps.

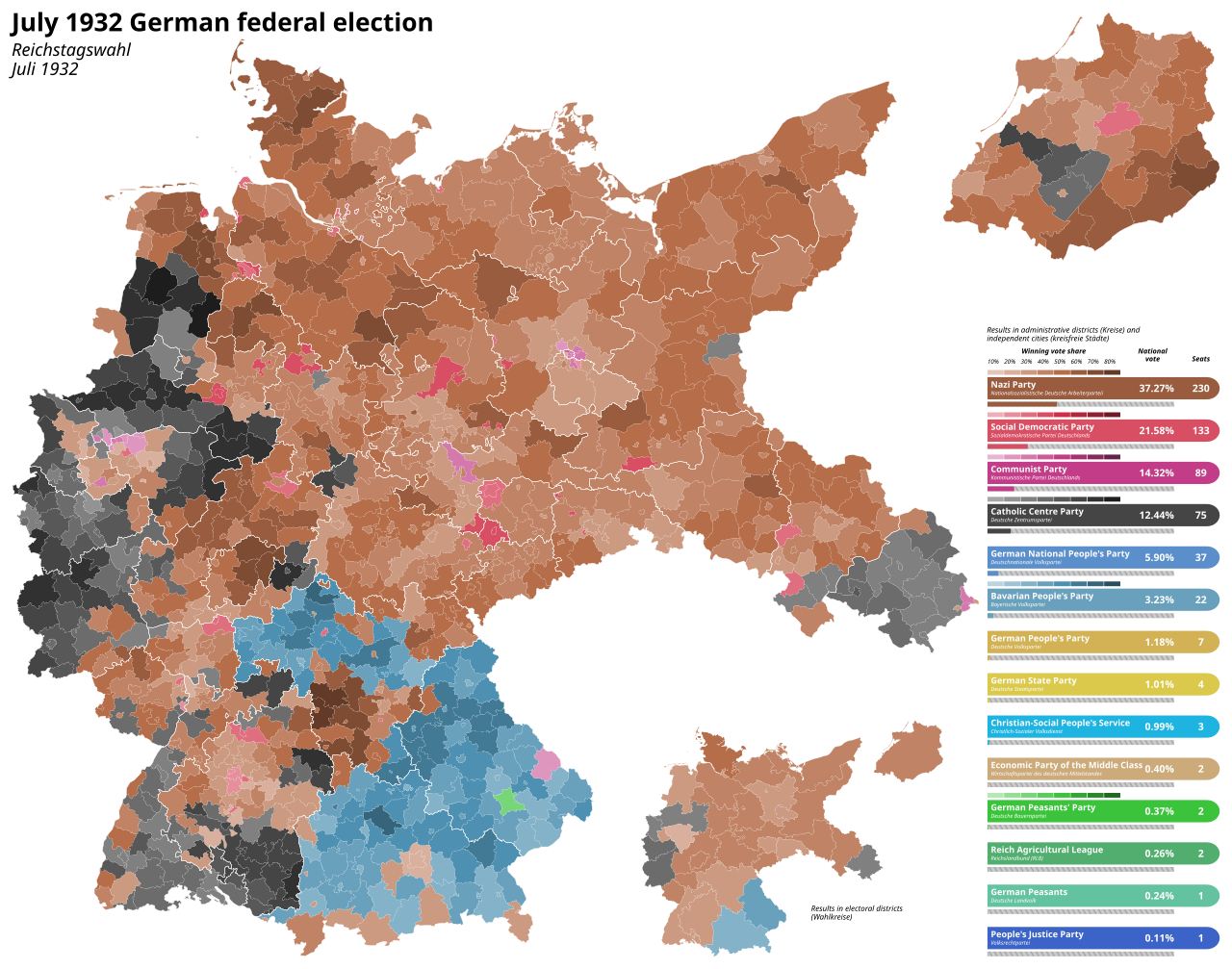

The decisive break came in July 1932, when Germany held another parliamentary election.

This time, Hitler pulled out all the stops in campaigning.

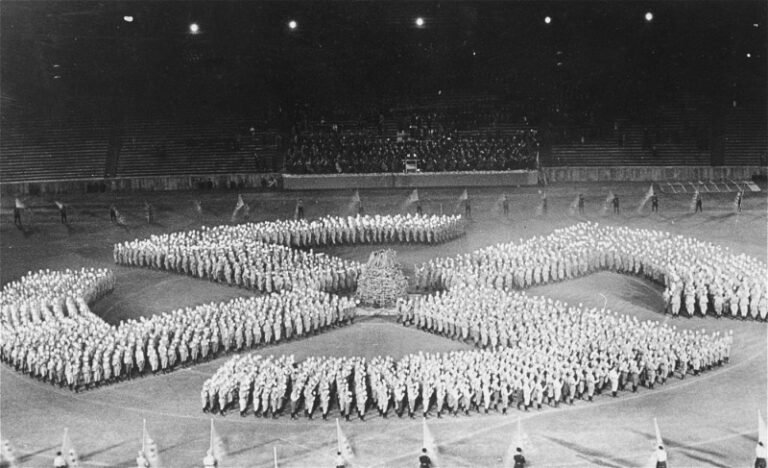

The Nazis even enlisted modern marketing techniques; they plastered every town with their swastika-emblazoned banners, held torchlit parades to project strength, and staged rallies with almost religious fervor – choirs singing, the Führer appearing amid dramatic spotlights and ecstatic cheers. It was emotional theater, carefully calibrated. “Crowds are influenced mainly by images produced by the judicious employment of words and formulas,” wrote Gustave Le Bon decades earlier – and the Nazis proved masterful at using slogans and symbols to sway the masses.

Many ordinary Germans, worn down by years of hardship, were susceptible to the illusion that Hitler offered – the illusion of a simple fix, an illusion of restored greatness.

“In crowds it is stupidity and not mother wit that is accumulated,” Le Bon observed wryly of mass psychology.

Hard truths and nuanced policies had few takers in 1932; soaring rhetoric and scapegoats were much more attractive.

When the votes were counted in July, the Nazis had become the largest political party in Germany by a wide margin. They won roughly 37% of the national vote, translating to 230 seats in the Reichstag.

It was an impressive plurality, though still short of an absolute majority.

No other party came close (the Social Democrats were around 21%, the Communists around 14%, and the rest was splintered among various parties). Suddenly, the Nazi Party seemed to be the 800-pound gorilla in German politics.

At this juncture, one might ask: Doesn’t this look like a democratic election result putting the Nazis on top? Superficially, yes – the Nazis achieved their largest vote share ever in a free election. But crucially, fewer than four in ten German voters put their mark against their name.

A majority of voters still preferred other parties.

The trouble was, Germany’s democratic institutions were so fractured that forming any stable government without the Nazi Party was becoming nearly impossible.

The Weimar constitution’s system of proportional representation meant no single party could govern alone unless it had over 50% of the vote, which no one had. Normally, parties would form coalitions.

Yet Hitler refused to participate in any coalition unless he was made Chancellor – he wanted the top job, nothing less.

Meanwhile, the traditional conservative and centrist parties were themselves too weakened to cobble together a majority, and they were extremely reluctant to cooperate with the Communists on the left. German politics had become a zero-sum game between Nazis and Communists, with the old establishment stuck in the middle, increasingly desperate and willing to consider extreme measures.

It’s here that we meet some of the true “gravediggers of democracy” – not only Hitler and his Nazi conspirators, but the conservative elites who ultimately handed power to Hitler in a fatal act of hubris.

After the July 1932 election, President Hindenburg – that grizzled symbol of the old order – was under pressure.

Hitler, as leader of the largest party, demanded that Hindenburg appoint him Chancellor (the head of government).

His justification based on a simple calculation – that if 51% of the vote was necessary for one party to rule, that with 37% of the vote (and as the largest party in parliament) the Nazis had 75% of the power that is necessary to govern and should be first in line.

An adventurous feat of political-mathematical acrobatics.

The irony of Hitler’s bid for power in 1932 must be underlined by his complete unsuitability for the position of Chancellor at the start of the year. Despite having given hundreds of speeches, before millions of people, and never actually having entered an election to even sit as a politician in the Reichstag: Hitler remained a stateless immigrant until January 1932.

At which point, he was granted a post as a mid-level civil servant assigned to the Braunschweig legation in Berlin – a matter orchestrated by the National Socialist interior minister of Braunschweig.

With this he became a German citizen, swore an oath of loyalty to the German constitution, and was signed up for a generous retirement plan from age sixty-five and annual salary of 5,238RM (approximately $27,000).

Hindenburg loathed Hitler personally and was skeptical of the upstart “Bohemian corporal,” so he initially refused any possibility of the Nazi leader attaining control of the government.

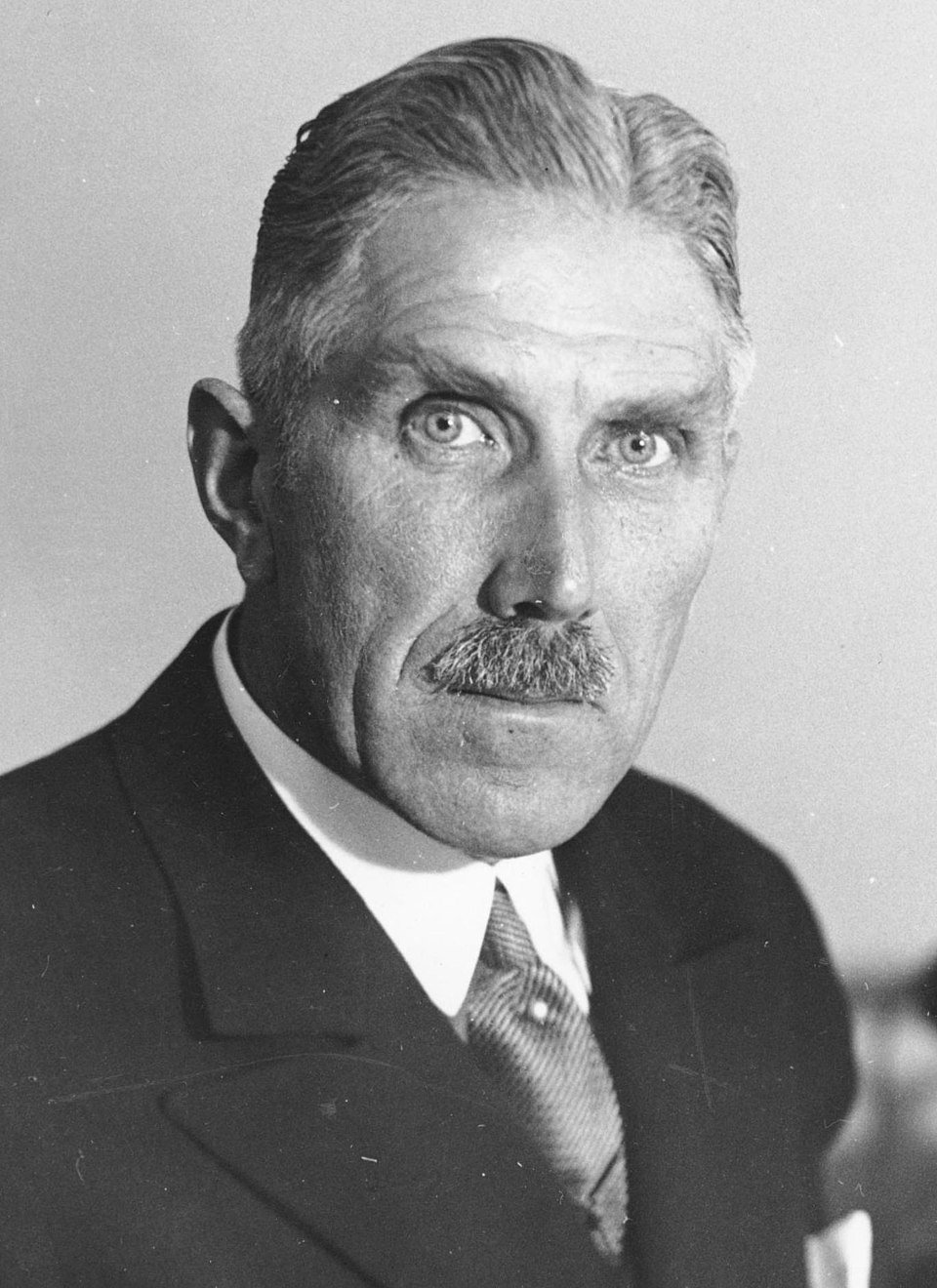

Instead, Hindenburg kept the ineffectual Franz von Papen as Chancellor with his ‘cabinet of monocles’ for a while longer.

Papen, a aristocratic former army officer, had no support in the Reichstag (his conservative Catholic party was a minor player by then), but he governed by Hindenburg’s grace and emergency decrees.

Papen did something drastic: he dissolved the Reichstag and called for yet another election in November 1932, hoping perhaps the Nazi tide would recede or that he could strengthen his hand.

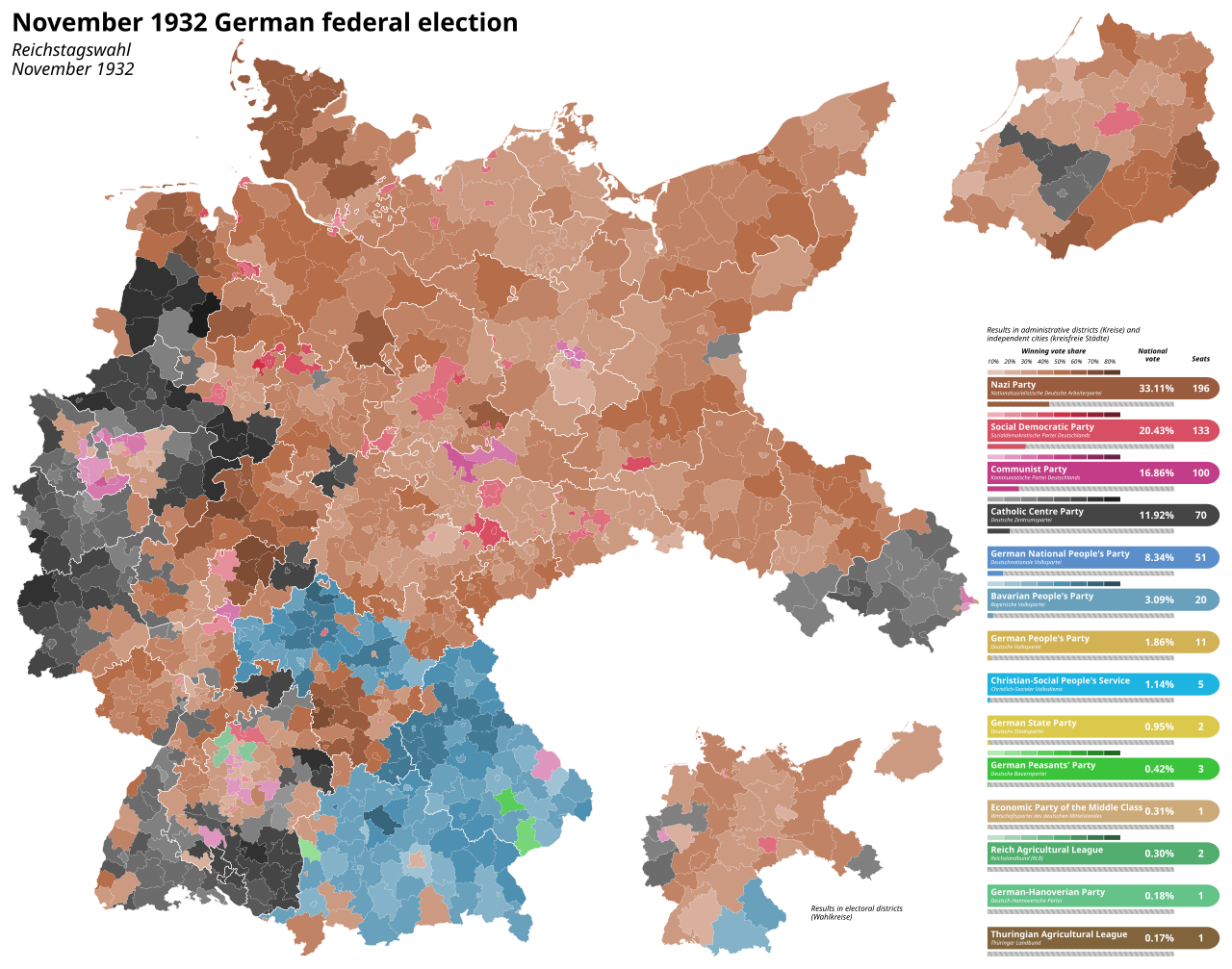

In that November 1932 election, the Nazis did in fact lose some ground – their vote share dropped to about 33%, and they lost 34 seats.

It appeared their momentum might be waning; some Nazi supporters were getting frustrated by Hitler’s inability to actually seize power and by the slight economic uptick that was beginning. Indeed, internal Nazi documents from late 1932 show the party was in serious financial trouble and hemorrhaging members.

A famous commentator quipped at the time, “Hitler is a man with a great future behind him.”

If Germany’s establishment had held firm then – if they had weathered the storm a bit longer – history might have turned out differently. As historian Timothy Ryback and others have noted, by late 1932 the Nazi movement was somewhat weakened and the economic outlook was improving modestly. But this is where political intrigue and the miscalculations of a few powerful men gave Hitler the opening he needed.

After Papen’s gambit failed to produce a governing majority, Hindenburg reluctantly appointed a new Chancellor: General Kurt von Schleicher in December 1932.

Schleicher was Hindenburg’s advisor and a key backstage player – a cunning conservative who thought he might tame the Nazis by luring some of their more left-leaning members away (he tried to split the party by negotiating with Nazi organizer Gregor Strasser). This failed miserably, and Schleicher’s government floundered within weeks.

At this point, ex-Chancellor Papen, humiliated but still influential, saw a path back to power for himself – and it went through Hitler.

Papen began secret talks with Hitler in January 1933. The idea (in Papen’s mind) was elegant: they would make Hitler Chancellor at the head of a coalition cabinet, but surround him with traditional conservative ministers so he’d be boxed in. “We’ve engaged him for ourselves,” Papen supposedly boasted to a colleague, implying that Hitler would be a mere figurehead whom Papen and company would actually control from behind the scenes. It was an absurd underestimation – akin to trying to ride a tiger and assuming it could be steered like a tame horse. Instead of steering the Nazi tiger, they were firmly in its jaws.

Papen was about to learn the hard way that Hitler was no one’s puppet.

Nevertheless, Papen convinced the aging President Hindenburg to go along with this plan. Hindenburg, who had sworn never to hand power to the rabble-rouser Hitler, was reassured by Papen that the risk was minimal: only a few Nazis would be in the cabinet, and Papen himself would be Vice-Chancellor to keep an eye on Hitler.

The industrial magnates and Junker landowners (Germany’s traditional elites) also signaled to Hindenburg that they preferred Hitler in power over the continuing instability or – worse in their view – a possible communist takeover.

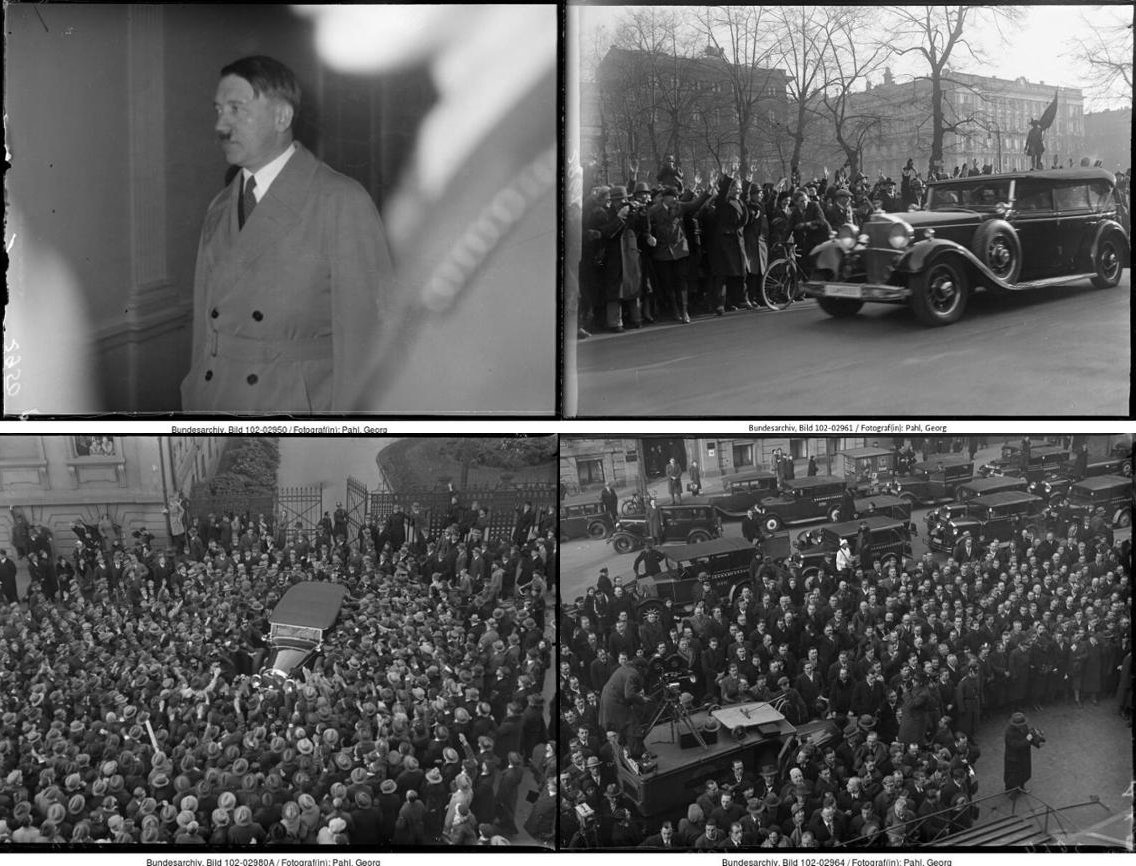

So, on January 30, 1933, Hindenburg formally appointed Adolf Hitler as Chancellor of Germany.

Hitler had not achieved this position by winning a democratic majority or by a violent coup; he had been handed the keys of power by the very conservative establishment he had been vowing to destroy, in a backroom deal born of desperation and arrogance.

As Ian Kershaw aptly put it, Hitler was “levered into power” by a coterie of influential men.

The Nazis themselves would later mythologize this moment as the Machtergreifung, the “seizure of power,” as if they had dramatically overthrown the state. In truth, one might cynically say power was there for the taking because those entrusted with defending the democratic republic essentially surrendered.

They dug the grave and invited Hitler to deliver the eulogy for Weimar democracy.

–

The Machtergreifung – The Nazi Party Seizure Of Power

“When Adolf Hitler became chancellor of Germany on January 30, 1933, his conservative allies, headed by Deputy Chancellor Franz von Papen, along with those conservative and nationalist leaders who supported von Papen’s Hitler experiment, expected to manage the untrained new head of government without difficulty. They were confident that their university degrees, experience in public affairs, and worldly polish would give them easy superiority over the uncouth Nazis. Chancellor Hitler would spellbind the crowds, they imagined, while Deputy Chancellor von Papen ran the state.”

Robert O. Paxton, author of The Anatomy Of Fascism

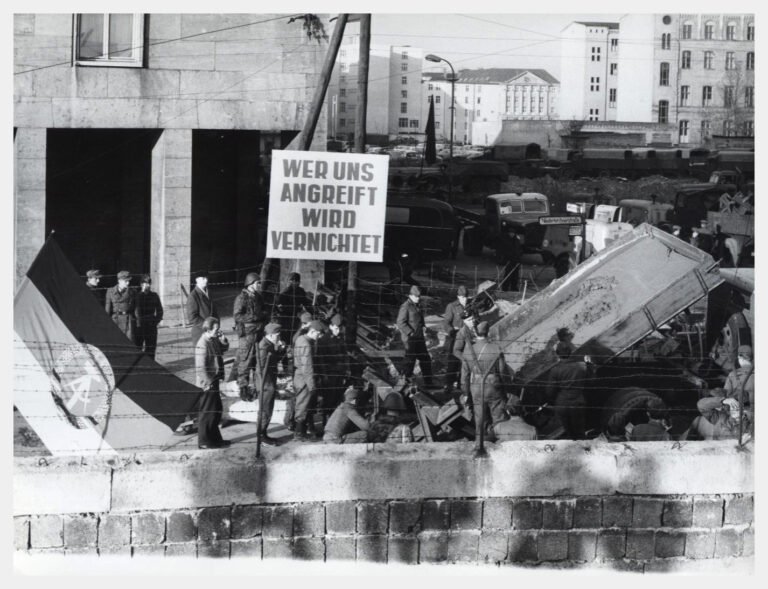

On the evening of January 30th 1933, Berliners gathered at the Brandenburg Gate witnessed a surreal spectacle.

Throngs of uniformed Nazis and their allies marched through into the city’s central historic district carrying torches, singing party anthems and chanting victoriously. Columns of SA stormtroopers goose-stepped with triumphant fervor. The air was thick with anticipation, fear, and – for the supporters of Hitler’s movement – jubilation.

For the Nazis and their supporters, this was the dawn of a new era – the birth of the Third Reich.

As of January 30th 1933, Germany was technically still a democracy – albeit one now led by a Chancellor who openly disdained the parliamentary republic he was sworn to serve. The real question was, how long would it remain one?

The democratically elected Reichstag was still in existence on that day Hitler took office, and Hindenburg, though elected (he’d been re-elected President in 1932, defeating Hitler in a runoff), used his constitutional powers to appoint Hitler in a wholly legal, if undemocratic, transfer of power.

Hitler’s cabinet was sworn in on January 30th with only two other Nazi ministers besides himself (Wilhelm Frick as Interior Minister and Hermann Goering without portfolio, soon controlling the Prussian police).

The remaining posts – Defense, Foreign Affairs, Economy, etc. – were held by conservatives from Papen’s circle or non-Nazi experts.

At first glance, it was a coalition government, not an outright Nazi regime.

This gave some Germans a false sense of security; it looked like Hitler was hemmed in. But Hitler had secured the key levers of power that he needed to dominate. As Chancellor, he could now call elections and use state resources to his advantage. And crucially, through his crony Goering, who took charge of Prussia’s large police force, Hitler had control of the largest police apparatus in Germany. The stage was set for what followed – a rapid and brutal seizure of total control, step by step, all under the veneer of legality.

Only two days after Hitler took office, he persuaded President Hindenburg to dissolve the Reichstag yet again and call for new elections in March 1933. Hitler was confident that with the power of the state now at his disposal, he could secure a parliamentary majority for the Nazis and their allies.

The campaign for the March 5, 1933 election was unlike any other in German history – it was conducted under an atmosphere of terror.

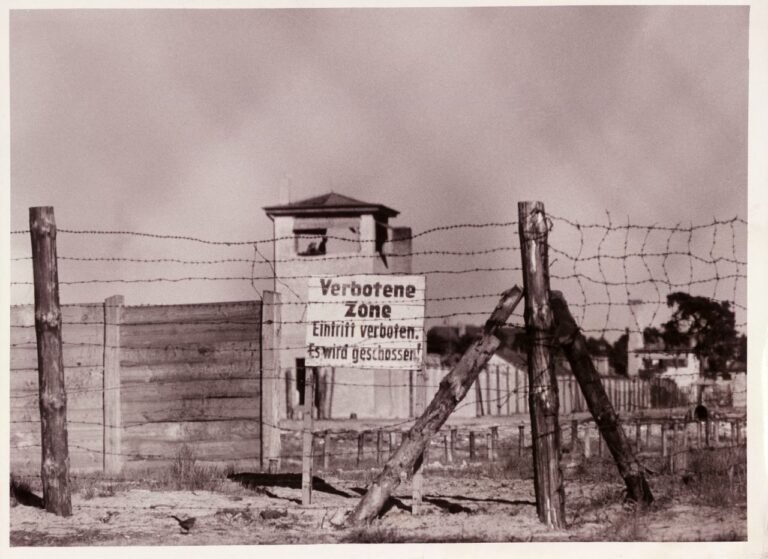

The Nazi SA and the police (now effectively working hand-in-hand) unleashed a wave of intimidation against left-wing and centrist parties. Opposition meetings were broken up by force. Communist and Social Democrat newspapers were banned or strictly censored. Thousands of political opponents found themselves beaten in the streets or thrown into makeshift jails.

In late February came the pivotal event that Hitler seized upon to justify his crackdown: the Reichstag Fire.

On the night of February 27, 1933, the Reichstag building (the German parliament) in Berlin burst into flames, its dome illuminated by a hellish glow. A lone Dutch communist named Marinus van der Lubbe was found at the scene and arrested for arson. To this day, historians debate whether van der Lubbe acted alone (as he claimed) or whether the Nazis had a hand in starting the fire to create a pretext.

Either way, Hitler and his inner circle wasted not a second in exploiting the incident. Hitler rushed to the scene and, in a state of high excitement, declared to his conservative coalition partners that this was a communist insurrection in progress.

He convinced the elderly President Hindenburg that the fire was the signal for a Bolshevik revolution and that draconian measures were needed immediately to save Germany.

The very next day, Hindenburg – at Hitler’s urging – signed the Reichstag Fire Decree (officially the “Decree of the President for the Protection of People and State”). This emergency decree suspended key civil liberties guaranteed by the constitution.

Overnight, Germans lost their protections against arbitrary arrest, free speech, free assembly, and privacy of communications. The police (now effectively controlled by Nazis) could enter and search homes without warrants, confiscate property, and detain people indefinitely without charges.

It is hard to overstate the significance of this: the legal foundation of a police state was laid in a single stroke, just four weeks into Hitler’s chancellorship.

Armed with the Reichstag Fire Decree, the Nazis moved swiftly to neutralize their most feared opponents – the Communists. Thousands of Communist Party members, including all of its Reichstag delegates, were rounded up and imprisoned. Some were beaten or tortured; some simply disappeared. Before the March election could even take place, Hitler had effectively decapitated the communist opposition and terrified much of the rest.

The election of March 5, 1933, thus occurred in a climate of pervasive fear and coercion. Nazi stormtroopers stood guard at polling places, watching as people cast their votes. Propaganda dominated the radio and public space; anti-Nazi literature was scarce or underground.

Astonishingly, despite all this, a significant portion of the German electorate still resisted the Nazis.

The Nazis on their own obtained about 43.9% of the vote – an increase from November, but still not an absolute majority.

In coalition with their DNVP (German Nationalists) allies – the remaining conservative nationalist party which got around 8% – they managed to control a slim majority of seats in the new Reichstag.

It was enough for Hitler’s immediate purposes.

One might pause here to reflect: even under conditions bordering on terror, more than half of German voters in March 1933 cast their ballots for parties other than the Nazis or their Nationalist partners.

Social Democrats and Communists together still got over 30% of the vote (despite the Communist Party being semi-outlawed during the election), and other small parties took the rest.

This underscores that Hitler never had anything like a sweeping mandate from a majority of Germans in a free, fair contest. His support was vast, but so was the opposition to him – until he rendered that opposition powerless by force.

The democratic process was only the shell within which Hitler worked; inside, he had introduced naked authoritarian coercion.

With a Reichstag majority in hand (thanks to the combination of Nazi and Nationalist deputies), Hitler moved to consolidate his grip in the most crucial way yet. The German parliamentary system still technically stood – and Hitler wanted to permanently neuter it.

Thus came the proposal of an Enabling Act.

Formally titled the “Law to Remedy the Distress of People and Reich,” the Enabling Act was a short bill with momentous implications: it would give Hitler’s government the right to enact laws without the participation of the Reichstag, even laws that deviated from the constitution, for a period of four years.

In essence, it was a self-dissolution of parliamentary democracy – a legal dictatorship.

To become law, the Enabling Act needed a two-thirds majority of the Reichstag (since it was effectively a constitutional amendment). Hitler set about obtaining this supermajority through a mix of pressure and guile.

When the new Reichstag met on March 23, 1933, it convened not in its fire-damaged building but in the ornate Kroll Opera House.

Outside, ranks of SA and SS men surrounded the building, a not-so-subtle message to any delegates who might be thinking of dissenting. The Communists, who had won 81 seats, were absent – imprisoned or in hiding – thus conveniently reducing the number of votes needed for two-thirds. The Social Democrats (the SPD), brave but isolated, were the only party left inclined to vote no.

Hitler needed the support of the Catholic Centre Party and some smaller allies to reach two-thirds.

To win them over, he gave a speech full of hollow promises – he swore that the new powers would not upset the role of the Reichstag, that the rights of the churches would be protected, and that the government would use its new authority only to achieve desperately needed national revival.

It was all lies or half-lies, of course, but many Centrists were eager to believe anything that might secure their interests in a Nazi-led Germany.

Under intense pressure and naive hope that Hitler might keep his word, the Centre Party and others caved.

Only the Social Democrats, led by Otto Wels, stood up amid intimidation to oppose Hitler. Wels gave a courageous speech, knowing it could be his last in a free and democratic Germany.

The rest of the chamber – nearly 441 deputies – voted in favor of Hitler’s Enabling Act.

The Social Democrats’ 94 votes against were irrelevant.

Democracy had just voted itself out of existence.

Gleichschaltung - One Hundred Days of Hitler

“Many of the ‘ideas’ enthusiastically propagated and ruthlessly put into practice by the Nazis predate Hitler’s ‘seizure of power’ and even the founding of the NSDAP … The view of Nazism as an aberration, a society inexplicably gone mad, or taken over by a ‘criminal clique’ against its will, has not been corroborated by the historical evidence.”

David F. Crew, historian

With the Enabling Act’s passing, the Nazi seizure of power was essentially complete in a formal sense. Hitler now had the legal authority to rule by decree without any legislative input. He was, for all intents and purposes, a dictator – and he had gotten there through a combination of legal procedure and terror.

One might reflect on the philosophical absurdity here: a democratic body used its lawful powers to annihilate both that law and itself – truly an act of political self-destruction, or as one historian called it, “state suicide.”

The Nazis lost no time capitalizing on their carte blanche.

What followed in the next months of 1933 was a process the Nazis proudly called Gleichschaltung, or “coordination” – meaning the alignment of all institutions and aspects of society with Nazi ideology and control.

In practice, it was a whirlwind of bans, purges, and takeovers:

- State and local governments were quickly “coordinated.”

- Nazi Reich commissioners were appointed to run Germany’s federal states (Länder), ousting any remaining democratic or non-Nazi officials.

- Elected state parliaments were dissolved or neutralized.

- Germany’s federal structure effectively ceased to function as all power centralized under Hitler’s regime in Berlin.

Trade unions were a potential source of opposition (especially since unions had ties to the socialist and Catholic parties). On May 2, 1933, the day after international Labor Day – cynically co-opted by Hitler as a national holiday – Nazi stormtroopers raided union offices across the country, dissolving all independent unions. Union leaders were arrested and beaten, union funds confiscated. In their place, the regime established the “German Labor Front,” a giant Nazi-run organization meant to represent all workers and employers – in reality, a means to control workers and prevent strikes (which were now outlawed).

Opposition political parties were banned one by one.

The Communist Party was already effectively outlawed since the Reichstag Fire.

The Social Democratic Party, the historic standard-bearer of German democracy, was banned in June 1933 and its members chased into exile or concentration camps.

The smaller parties – liberals, conservatives, and Catholics – dissolved themselves under pressure through the summer of 1933, often in exchange for vague promises or simply to avoid confrontation.

By July 1933, a new law proclaimed the Nazi Party to be the only legal political party in Germany.

The era of elections (with any real choice) was over; Hitler’s totalitarian one-party state had been born.

Through the “Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service” in April 1933, the regime purged the civil service of anyone deemed politically unreliable or “non-Aryan” (which meant Jews, even those who had served since the Imperial era, as well as known democrats). Professors, judges, bureaucrats – thousands were forced out, replaced by Nazi loyalists or party members. This law was one of the first concrete anti-Jewish measures of the new government: it effectively barred Jews from government jobs, a prelude to the broader persecutions to come. Schools and universities were also “coordinated,” with teachers compelled to join Nazi leagues and curricula rewritten to teach Nazi racial and nationalist doctrines.

Joseph Goebbels’ Ministry of Propaganda swiftly brought newspapers, radio, film, and arts in check. Editors who didn’t toe the Nazi line were removed; books deemed ‘un-German’ were ceremoniously burned in public bonfires (the infamous book-burnings of May 1933 saw works by Jewish, socialist, and liberal authors consigned to the flames by gleeful students and brownshirts). A new Reich Chamber of Culture dictated permissible art, music, and literature. The public sphere in Germany became a monologue – the Nazi voice, incessant and unchallenged.

The months after Hitler took power saw a proliferation of makeshift detention centers – improvised concentration camps – where the SA imprisoned enemies of the state.

The first official concentration camp, Dachau, was established in March 1933 near Munich under the command of Himmler’s SS, originally to incarcerate political prisoners (mostly Communists and Social Democrats). Violence and intimidation didn’t cease just because Hitler had the legal tools; on the contrary, the early Nazi regime combined terror and law to paralyze any potential dissent.

All of this happened with dizzying speed – within the first 100 days of Hitler’s chancellorship.

Historian Peter Fritzsche, who chronicled this period, noted how rapidly Germans were confronted with a new reality: pluralism was gone, dissent was life-threatening, and many institutions they had known simply vanished or bowed to Nazi rule. The consolidation of power was so thorough that by the time most Germans realized what had happened, it was essentially too late.

The economy did begin to improve (though for reasons that were already in motion by early 1933, including global recovery and later rearmament efforts). Employment slowly picked up as the regime launched public works like highway (Autobahn) construction. There was a tangible sense for some that “things are getting done” after years of paralysis. And because the most brutal repression initially targeted Communists, Socialists, and Jews – groups that significant portions of the German public were prejudiced against or saw as “outsiders” – a lot of people shrugged off or rationalized the mounting atrocities.

This interplay of coercion and consent is what historian Robert Paxton and others emphasize in explaining fascist takeovers. Nazi Germany was not a case of one day everyone waking up in chains; it was a series of steps where each step, taken in isolation, did not always provoke universal outrage, and many chose to conform rather than resist.

As David F. Crew and other scholars have argued, however, we cannot comfort ourselves by thinking the Nazis simply imposed tyranny on a completely unwilling populace. The ugly truth is that plenty of Germans made their Faustian bargain with Hitler. By the middle of 1933, Hitler’s regime even enjoyed a kind of popularity, buoyed by propaganda that painted him as the savior of the nation.

A “Hitler myth” was cultivated, presenting him as a near-infallible leader who had miraculously rescued Germany from chaos and humiliation.

What happened to the conservatives like Papen, Hindenburg, and the aristocrats who thought they would manage Hitler? In the short term, they were either sidelined or co-opted. Papen himself lasted only a little while as a nominal Vice-Chancellor, soon pushed into a diplomatic role far from the center of power.

Other conservative ministers found that real decisions were increasingly made by Hitler and his Nazi cohort, and if they objected, they met with blunt dismissal.

President Hindenburg remained a figurehead until his death in August 1934. By then, Hitler had so consolidated power that when Hindenburg died, Hitler merged the presidency with the chancellorship, declaring himself “Führer and Reich Chancellor,” answerable to none.

In sum, every pillar that could have supported democracy or limited Hitler was knocked down, one after another.

By the end of 1933, the Weimar Republic was definitively dead and buried.

The Nazi Party was not only in power, it was the state.

It’s worth briefly comparing this trajectory briefly to other authoritarian takeovers. In Russia, the Bolsheviks in 1917 had bypassed democracy almost entirely – they seized power in a coup and then dissolved the democratically elected Constituent Assembly that dared to oppose them. In Italy, Mussolini came to power in 1922 not through winning an election (his Fascists were actually a small party at the time) but by threatening a coup – the March on Rome – which pressured the king to appoint him Prime Minister. Mussolini then gradually dismantled Italian democracy by 1925 through a mix of new laws, intimidation, and murder of opponents (like the socialist Matteotti). In Spain, the slide to dictatorship came via civil war: the collapse of the political center and mutual intransigence of left and right led to the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939), out of which General Franco emerged as a victorious dictator – again, not elected by popular vote but imposed by force of arms.

Compared to these, Hitler’s path to dictatorship was somewhat unique.

He neither launched a full-scale coup nor fought a civil war; instead, he leveraged the institutions of a democracy to pave his way, then used a blend of electoral legitimacy and outright thuggery to cement his rule.

**

Conclusion

NO – the Nazi Party was not democratically elected.

Even in March 1933, following the Reichstag fire, with the Social Democrats in exile and the Communist Party members either detained in concentration camps or hiding underground, the Nazis only received 43.7% of the vote.

At no point, in any free and fair election in the 1920s or 1930s, did the Nazi Party receive a majority of the votes cast.

Thus, to the extent the Nazi Party’s ascent to the chancellorship was legal and involved elections, it was indirect and far from purely democratic. Yes, the Nazis had garnered a large plurality of votes – a substantial minority of Germans had voted for them, which gave Hitler leverage. But Hitler did not come to lead Germany by winning an outright mandate of the people. He came to lead because other politicians thought they could manipulate the popular extremist for their own ends.

A catastrophic miscalculation that enabled a party intent on destroying democracy to subvert it from within.

***

If you’ve enjoyed reading this article, consider booking one of our private guided tours of Berlin.

HISTORICAL ARTICLES

Mythbusting Berlin

Are There Any Nazi Statues Left In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

Visitors to Berlin often arrive expecting to find the physical remnants of the tyranny of the 20th century still standing – statues of dictators, triumphal arches, or bronze idols. Instead, they often find none. The stone symbols and statues of the Third Reich are still gazing down on them, however, hiding in plain sight. But why are there no statues of Hitler? Did the Allies destroy them all in 1945, or is the truth stranger

Could The Western Allies Have Captured Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

To contemplate a Western Allied capture of Berlin in 1945 is to challenge the established endgame of the Second World War. What was the true military and logistical feasibility of a Western Allied assault on the Nazi capital? What factors truly sealed Berlin’s fate, and what might have changed had the Allies pushed eastward?

Answering these questions means delving into the complex interplay of logistics, political maneuvering, and the competing visions for a post-war world

Did Any Of The Rothschild Dynasty Die In The Holocaust? – Mythbusting Berlin

The Rothschild name is synonymous with immense wealth, influence, and persistent conspiracy theories—especially during the era of Nazi Germany. Often targeted by antisemitic propaganda, the family’s survival during World War II has sparked myths about their supposed immunity from Nazi persecution. But did any Rothschild family member actually perish in the Holocaust? This article explores that compelling question, unraveling historical misconceptions and revealing the reality behind one of Europe’s most famous dynasties.

Did Frederick The Great Introduce The Potato To Germany? – Mythbusting Berlin

One of the more bizarre claims to fame attributed to the first King of Prussia is that the man who would go down in history known as Frederick the Great introduced the potato to Germany during his reign back in the 1700s. This starchy root vegetable has undoubtedly become a staple part of German cuisine – an essential addition to any plate of Schnitzel, Schweinshaxn, and Königsberger Klopse – however, whether Frederick the Great is

Did Hitler Escape To Argentina In 1945? – Mythbusting Berlin

Although Nazi leader, Adolf Hitler, certainly remains an inescapable figure, could there be any truth to the story of his escape to Argentina in 1945? That the most wanted man on earth could simply vanish, to spend the rest of his life peacefully in South American obscurity captivates imaginations. Yet, despite numerous investigations, this tale persists primarily as myth—fueled by speculation, hearsay, and conspiracy theories.

Did Hugo Boss Design The Nazi Uniforms? – Mythbusting Berlin

The idea that Hugo Boss – the man whose name now adorns expensive suits and fragrances – was the creative genius behind the Nazi uniforms suggests a terrifying collision of haute couture and holocaust – a marriage of high style and high crimes. The image is striking: a German tailor sketching the ultimate villain’s costume. But history, as usual, is far messier, more bureaucratic, and more banal than the internet memes suggest. To understand who

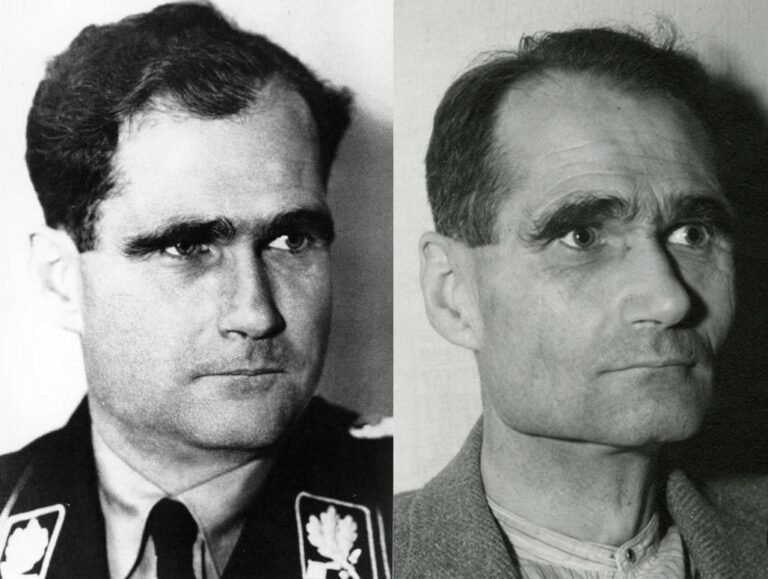

Did Rudolf Hess Really Commit Suicide? – Mythbusting Berlin

On a summer’s day in 1987, the last Nazi war criminal of the Nuremberg trials was found dead in a prison built for hundreds, yet for two decades, housed only him. The official verdict was suicide, a straightforward end to a life defined by fanaticism, delusion, and contradiction.

But the simplicity of the report belied the complexity of the man and the 46 years he had spent in Allied custody. In the meticulously controlled

Did The Nazis Develop Nuclear Weapons? – Mythbusting Berlin

The Nazi obsession with super-weapons became so serious in the closing stages of the Second World that Adolf Hitler personally believed that such ‘Wunderwaffen’ both existed in a usable form – and would save the country from defeat. Had the Nazis managed to develop nuclear weapons by 1945 – the outcome of the war would surely have been different. But how close were Hitler, Himmler, and his henchmen to developing an A-bomb?

Did The Nazis Invent Decaf Coffee? – Mythbusting Berlin

Persistent rumors claim that Nazis preferred their coffee anything but pure, leading some to wonder if they might have influenced the development of decaffeinated coffee. Although decaf was already widely available across Europe by the mid-20th century, speculation continues: could the Nazis really have played a role in popularizing—or even discovering—this caffeine-free alternative, or is this simply another caffeinated conspiracy cooked up to sensationalize an ordinary historical detail?

Did The Nazis Invent The Bicycle Reflector? – Mythbusting Berlin

The fruits of wartime ingenuity are plenty – so many, in-fact, that it has become somewhat of a worn cliche that as the guns start firing the innovators get to work, often solving problems while providing more problems for the enemy to overcome.The kind of progress that results in the production of newer improved, more lethal weapons, such as to increase the chances of victory.

Did The Nazis Run The Largest Counterfeiting Operation In History? – Mythbusting Berlin

During the Second World War the Nazis masterminded an astonishing plot to destabilise Britain by flooding its economy with counterfeit banknotes. Crafted in secret by concentration camp prisoners, this forged fortune became the most ambitious counterfeiting operation ever attempted. But was it history’s largest? Dive into the extraordinary tale of Operation Bernhard,

rife with deception, survival, and intrigue—revealing the truth behind one of the Third Reich’s most audacious schemes and its surprising legacy.

Did The Second World War End In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

When is a war ever truly over? When the last shot is fired in anger would seem like the best measure. Rarely, though, is it possible to gain insight into such a moment.

Remarkably, a record still exists of such a moment at the end of the First World War on the Western Front. A seismic register and recording of the last belching battery of British guns firing artillery across no-man’s-land, followed by a profound

Did The Spanish Flu Pandemic Help The Nazis Take Power? – Mythbusting Berlin

The devastating Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918-1919 struck amid Germany’s post-war turmoil, compounding social instability, economic hardship, and widespread political disillusionment. Could this catastrophic health crisis have indirectly paved the way for Nazi ascension? While often overshadowed by war and revolution, the pandemic’s profound psychological and societal impacts arguably contributed to the perfect storm, enabling extremist ideologies—including Nazism—to gain popularity and ultimately seize power in a fractured Germany.

Have Adolf Hitler’s Remains Been DNA Tested? – Mythbusting Berlin

In the smouldering ruins of Berlin in 1945, the world’s most wanted man vanished. Did Adolf Hitler, as official history attests, die by his own hand in the Führerbunker? Or did he escape, fuelling a thousand conspiracy theories that have echoed for decades? For years, the Soviets claimed to hold the gruesome proof of his death: a skull fragment and a set of teeth, locked away in Moscow archives. But in an age of definitive

How Did The Nazi Concentration Camps Differ From The Soviet GULAG?

The Nazi concentration camps and Soviet Gulag system have often been conflated in popular imagination—twin symbols of twentieth-century totalitarian horror. Yet the two systems operated on fundamentally different principles. One extracted labor to fuel industrialisation while accepting mass death as collateral damage; the other evolved into purpose-built machinery of genocide. Understanding these distinctions isn’t merely academic—it reveals how different ideologies produce different atrocities, and why Germany and Russia reckon with these legacies so differently today.

How Long Did It Take To Build The Berlin Wall? – Mythbusting Berlin

It is one of the most enduring images of the 20th century: a city divided overnight. The popular narrative tells us that Berliners went to sleep in a unified city and woke up in a prison. While the shock of August 13th 1961, was very real, the idea that the ‘Wall’ appeared instantly is a historical illusion. The physical scar that bisected Berlin was not a static creation, but a living, malevolent beast that evolved

How Many Assassination Attempts On Adolf Hitler Were There? – Mythbusting Berlin

Nazi leader, Adolf Hitler, projected an aura of invincibility, a man of destiny shielded by providence. But behind the carefully constructed image of the untouchable Führer lies a story of constant threat, of bombs that failed to detonate, and errant bullets that missed their mark. Unearth the hidden history of the numerous attempts on Hitler’s life as we explore the courage of those who tried to change the course of history and the devil’s luck

How Many Jews Died In The Holocaust? – Mythbusting Berlin

The answer to the question posed of how many Jews died in the Holocaust is a simple one: too many. That merely one death was an unforgivable obscenity is a fundamental and necessary realisation in understanding the capriciousness of this unparalleled racial genocide. To comprehend, however, the full number of Jews murdered in Europe by the Nazi regime in the 1930s and 1940s is a detective story of epic proportions: the evidence overwhelming, multifaceted, and

How Many People Died Trying To Escape East Germany? – Mythbusting Berlin

The image of the Berlin Wall is seared into our collective memory, a concrete symbol of Cold War oppression. We think of the daring escapes and the tragic deaths of those who failed. But that well-known number is only a fraction of the truth. The story of those who died trying to escape East Germany is far broader and more complex than most imagine, stretching along a thousand-kilometer border and out into the cold waters

How Old Is Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

A relatively new arrival in Europe, Berlin is over 1000 years younger than London, nevermind Rome or Athens, Jerusalem or Jericho. Just how old is Berlin though?

A question fraught with false assumptions and distortions – that has more often than not been answered with propaganda as it has with the cold hard truth.

Was Adolf Hitler A Drug Addict? – Mythbusting Berlin

Solving the enigma of the ‘Führer’ has become a preoccupation for many, since the arrival of the Austrian-German onto the world stage – although moving beyond the mythology without falling into the trap of prejudically extrapolating on the psychopathography of Hitler or demonising so as to excuse his actions has proven problematic. What to make of the man who became more than the sum of his masks? The painter; the military dilettante, the mass murderer,

Was Adolf Hitler A Freemason? – Mythbusting Berlin

History abhors a vacuum, but adores a mystery. Such is the speculative fiction suggesting a secret allegiance behind the rise of the Third Reich – that the catastrophe of the Second World War was orchestrated from the shadows of a Masonic lodge. The image of Adolf Hitler—the drifter from Vienna turned dictator—as a covert initiate of the very brotherhood he publicly reviled, however, creates a paradox that collapses under scrutiny. As when we unlock the

Was Adolf Hitler Gay? – Mythbusting Berlin

In the shadowy corridors of Third Reich history, few questions provoke as much tabloid curiosity and scholarly exasperation as the sexuality of Adolf Hitler. For decades, rumors have swirled—whispered by political enemies in 1930s Munich, psychoanalyzed by American spies in the 1940s, and sensationalized by revisionist authors today. Was the dictator who condemned thousands of men to concentration camps for “deviant” behavior hiding a secret of his own? By peeling back the layers of propaganda,

Was Adolf Hitler Jewish? – Mythbusting Berlin

Was the dictator who orchestrated the murder of millions of European Jews secretly one of them? It is perhaps the darkest irony imaginable, a story whispered for decades in backrooms, bars, and conspiracy forums alike. The most-common rumour – the ‘Frankenberger Myth’ – suggests that Adolf Hitler’s paternal grandfather was Jewish, a secret so damaging it could have unraveled the entire Nazi regime. But where does this claim come from? And, more importantly, is there

Was Currywurst Invented In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

Explore the story behind what many consider Berlin’s most iconic snack—the ever-so-humble Currywurst. Often hailed as an enduring symbol of culinary creativity amid Cold War scarcity, this humble dish has inspired fierce debate about its true origin. But was it genuinely invented here in Berlin, or have proud locals simply adopted and elevated this spicy street-food favorite into legendary status all their own?

Was Fanta Invented By The Nazis? – Mythbusting Berlin

As one of the most secretive organisations in the world, the Coca Cola corporation refuses to share its secret recipe with anyone. Famously insisting only on shipping the base syrup of its drinks to plants around the world to be carbonated and distributed.

This combined with the trade limitations of the Second World War may have led to the introduction of one of the most popular soft-drinks in the world. But could it be true:

Was Frederick The Great Gay? – Mythbusting Berlin

Frederick II of Prussia, better known as Frederick the Great, is often remembered as the archetypal enlightened monarch – a brilliant military commander, patron of the arts, and learned philosopher. Yet behind the stern portraits of this 18th-century warrior-king lies a personal life long shrouded in intrigue and speculation. Intrigue around the king’s sexual orientation has persisted through the centuries, chiefly revolving around one question: Was Frederick the Great gay?

Was Henry Ford A Nazi? – Mythbusting Berlin

US auto tycoon, Henry Ford, holds the ignominious distinction of being the only American Adolf Hitler praised by name in his National Socialist manifesto: ‘Mein Kampf’. This was not, as it turns out, the only connection between Ford and the Party of Hitler, Himmler, and the Holocaust.

Ford’s overt affinity with the Third Reich reveals a troubling past. How deep these connections ran, and how consequential they were for both sides, is a chapter

Was The Colour Blue Invented In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

Tracing the true history of blue—from ancient Egyptian dyes to the accidental discovery of Prussian Blue in a Berlin lab. We’ll debunk myths about seeing blue, explore colonial indigo plantations, scale mountains with a cyanometer, and trace Van Gogh’s starry skies—all to answer one question: how did Berlin shape our understanding of the world’s rarest color?

Was The Döner Kebab Invented In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

Unlikely icon of immigrant success; fast food symbol of the working class; over-hyped midnight disco eat; or culturally appropriated cuisine? Its influence goes far beyond layers of seasoned meat and fresh vegetables stuffed into pita bread. But does Berlin deserve credit as the Döner Kebab’s true birthplace, or has the city merely refined and popularized a culinary tradition imported from elsewhere?

Was The Fall Of The Berlin Wall An Accident? – Mythbusting Berlin

On a seasonally crisp night in November 1989, one of the most astonishing events of the 20th century occurred. After twenty eight years, three months, and twenty eight days of defining and dividing the German capital, the Berlin Wall ceased to exist – at least in an abstract sense. Although the removal of this symbol of the failure of the East German system would take some time, its purpose – as a border fortification erected

Was The Nazi Party Democratically Elected? – Mythbusting Berlin

The myth persists that Adolf Hitler rose to power through popular democratic choice. Yet history reveals a darker, more complicated truth. Hitler’s ascent involved exploiting democratic institutions, orchestrating violence, propaganda, and political intrigue—not a simple election victory. Understanding how Germany’s democracy collapsed into dictatorship helps illuminate the dangerous interplay between public desperation, elite miscalculations, and extremist ambition, providing crucial lessons for safeguarding democracy today.

Were The Allied Bombings Of Germany War Crimes? – Mythbusting Berlin

The history of the Allied bombing of Germany during the Second World War still triggers fierce debate. Was reducing cities to rubble a necessary evil – justice from above in a just war – or an unforgivable crime? Can the intentional targeting of civilians ever be justified as militarily necessary?

In a conflict where all rules seemed to vanish, an even more pertinent question persists: by the very standards they would use to judge their

Were The Nazi Medical Experiments Useful? – Mythbusting Berlin

Before the Nazi period, German medicine was considered the envy of the world – a shining monument to progress. But deep within that monument, a rot was spreading, one which would collapse the entire structure into an abattoir. From the wreckage, we are left with a profoundly uncomfortable inheritance: a moral enigma wrapped in doctor’s whites.

What to make of the data, the images, and the terrible knowledge gleaned from unimaginable human suffering. Whether

What Are The Origins Of The Nazi Salute? – Mythbusting Berlin

A specter is haunting the modern mind, a gesture so charged with the dark electricity of history that its mere depiction can unleash a storm of controversy.

It is a simple movement: the right arm, stiff and straight, raised to the sky. But in that simplicity lies a terrifying power, a symbol of a regime that plunged the world into an abyss and a chilling reminder of humanity’s capacity for organised hatred.

This

What Are The Origins Of The Nazi Swastika? – Mythbusting Berlin

Long before the legions of the Third Reich marched beneath its stark, unnerving geometry, the swastika lived a thousand different lives. It was a symbol of breathtaking antiquity, a globetrotting emblem of hope and good fortune that found a home in the most disparate of cultures. To even begin to understand its dark 20th-century incarnation, one must first journey back, not centuries, but millennia.

What Are The Pink Pipes In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

A first-time visitor to Berlin could be forgiven for thinking the city is in the midst of a bizarre art installation. Bright pink pipes, thick as an elephant’s leg, climb out of the ground, snake over pavements, arch across roads, and disappear back into the earth. Are they part of a complex gas network? A postmodern artistic statement? A whimsical navigation system? These theories, all logical, are all wrong. The truth is far more elemental,

What Do The Colours Of The German Flag Symbolise? – Mythbusting Berlin

What does a flag mean? Is it merely a coloured cloth, or does it hold the hopes, struggles, and identity of a nation? The German flag, with its bold stripes of black, red, and gold, is instantly recognisable. But the story of its colours is a tumultuous journey through revolution, suppression, and reinvention. The common explanation for their symbolism is a simple, romantic verse, yet the truth is a far more complex and contested tale,

What Happened To Adolf Hitler’s Alligator? – Mythbusting Berlin

It is often said that you can tell a lot about a person by their relationship with animals; that owners often come to look and behave like their pets. Or is it perhaps more that people choose their pets to correspond to their personality? Nazi leader Adolf Hitler’s love of dogs, for example, is well documented but what is there to make of his relationship with reptiles?

What Happenened To The German Royal Family? – Mythbusting Berlin

When the smoke cleared over the trenches in November 1918, the German Empire had evaporated, and with it, the divine right of the Hohenzollern dynasty. Conventional wisdom suggests the family simply vanished into the sepia-toned obscurity of history books—exiled, forgotten, and irrelevant. But dynasties, like weeds in a landscaped garden, are notoriously difficult to uproot entirely. The story of the German royals did not end with the Kaiser’s flight to Holland; it merely shifted gears.

What Is The Difference Between Fascism & Nazism? – Mythbusting Berlin

While the terms ‘Fascist’ and ‘Nazi’ are often bandied around interchangeably as shorthand for tyranny – Italian fascism and German National Socialism were distinctly different beasts. Albeit ideological kin. One an ideology of state-worship, born from post-war chaos and national pride; the other built upon a fanatical, pseudo-scientific obsession with race. Two peas in the same totalitarian pod – twins in tyranny – more succinctly summarised as the Nazi chicken to the Fascist egg.

What Was Checkpoint Charlie? – Mythbusting Berlin

Checkpoint Charlie remains among Berlin’s most visited historical sites, famed worldwide for its significance during the Cold War. Originally established as a modest border-crossing point, it evolved dramatically over the decades into an international symbol of freedom, espionage, and intrigue. Today, critics and locals often dismiss it as little more than a tourist trap—Berlin’s Disneyland—but how exactly did Checkpoint Charlie get its peculiar name, and what truths hide behind its popularity?

What Was Prussia? – Mythbusting Berlin

Prussia’s legacy is both remarkable and contentious—once a minor duchy, it rose dramatically to shape modern European history. Renowned for military discipline, administrative efficiency, and cultural sophistication, Prussia was instrumental in uniting the German states, laying foundations for a unified Germany. But how did this kingdom, with its roots in Baltic territories, achieve such prominence, and why does its complex history continue to evoke admiration, debate, and occasional discomfort in Germany today?

What Was The Berlin Airlift? – Mythbusting Berlin

In the ruins of 1948, the silence of Berlin was not a sign of peace, but a held breath before a new catastrophe. The city, drowning in rubble and political intrigue, became the staging ground for the twentieth century’s most audacious gamble. While popular history remembers the chocolate parachutes and smiling pilots, the reality of the Berlin Airlift was a terrifying operational nightmare born from a ruthless currency war. It wasn’t just a humanitarian mission;

What Was The Socialist Kiss? – Mythbusting Berlin

It is one of the most curious and enduring images of the Cold War: two middle-aged, grey-suited men, locked in a fervent embrace, their lips pressed together in a kiss of apparent revolutionary passion. This was the ‘Socialist Fraternal Kiss’, a ritual that, for a time, seemed to encapsulate the unwavering solidarity of the Eastern Bloc.

But what was behind this seemingly intimate gesture? Was it a genuine expression of camaraderie, a piece of

Who Built The Berlin Wall? – Mythbusting Berlin

One of the most common questions I have encountered from people curious about Berlin, and often so cryptically phrased. Who built the Berlin Wall? A simple five-word query, yet one that can be read one of two ways. More than thirty years since the ‘Fall of the Wall’, the story of its construction continues to baffle many who are mainly familiar with its existence through knowledge of its importance…

Who Really Raised The Soviet Flag On The Reichstag? – Mythbusting Berlin

One iconic photograph has come to symbolise the Red Army’s victory over Nazi Germany in 1945—the Soviet flag waving triumphantly above Berlin’s battered Reichstag building. Yet behind this enduring image lies controversy, confusion, and political manipulation. Who truly raised the Soviet banner atop the Reichstag? Was it a spontaneous act of heroism or carefully staged Soviet propaganda? Decades later, unraveling the truth reveals surprising layers beneath the mythologized symbol of Soviet triumph.

Who Was Really Responsible For The Reichstag Fire? – Mythbusting Berlin

Various theories have been posited as to who actually set fire to the German parliament in 1933. Was it the opening act in an attempted Communist coup or a calculated false flag operation carried out by elements of the Nazi Party, intended to create the conditions necessary for introducing single-party rule? And what part did the young man from Holland, arrested shirtless inside the building the night of the fire, play in this event?

Who Were The Last Nazis On Trial? – Mythbusting Berlin

More than eighty years after the Holocaust, courtrooms across Germany still echo with testimony from the final chapter of Nazi justice. Centenarian defendants in wheelchairs, their faces hidden behind folders, arrive to answer for crimes committed in their youth. These are not the architects of genocide—those men faced their reckoning at Nuremberg decades ago. These are the guards, the secretaries, the bookkeepers: ordinary people who enabled extraordinary evil. Their trials represent a legal revolution: the

Why Is Berlin The Capital Of Germany? – Mythbusting Berlin

There was little in its humble origins—as a twin trading outpost on a minor European river—to suggest that Berlin was destined for greatness. It sits on the flat expanse of the North European Plain, a landscape once dismissively referred to as the “sandbox of the Holy Roman Empire.” Unlike other world capitals, it lacks breathtaking scenery or a naturally defensible position. It is a city built not on majestic hills or a grand harbour, but