“Happy the people whose annals are blank in history books.”

Thomas Carlyle, History of Friedrich II of Prussia

Before Germany there was Prussia. Without Prussia there would have been no Germany.

Now Prussia is simply no more.

But what on earth was this mythical land anyway?

Vox pop that question publicly now and more often than not you will be met with stunned silence – or the awkward suggestion that it might have something to do with old mother Russia – or maybe Persia.

What exactly Prussia was has always been defined by the era in which the question has been asked.

By virtue of its wildly different forms, you would receive a different definition if the question were asked in 1945, 1845, or 1745. So old is the quandary that the same could be said for 1445 and 1245. A truly European dilemma.

What can be stated with great certainty is that Prussia no longer exists. Joining the long list of fellow fallen states: Biafra, Rhodesia, Gran Colombia, Sikkim, the Zulu Kingdom, the Orange Free State…

While many of these sovereign states have disappeared into obscurity, the impact of the rise and fall of the once mighty European power of Prussia can still be felt.

Europe without Germany now would be unimaginable but Germany without Prussia would be simply inconceivable. In more than one measure of the word.

Dealing with the question of the former – there would still be the awkward alliance of Austria and Switzerland, enough to preserve the diphthongs and clunky compound nouns (see: Donaudampfschifffahrtselektrizitätenhauptbetriebswerkbauunterbeamtengesellschaft) of the language, and the measurably superior original Viennese Schnitzel.

For better or worse, Europe without Germany would be a substantially different place, but Germany without Prussia would likely have never existed.

So integral as it was to the growth and eventual unification of Germany.

From its colonial origins in the forcible Christianisation of the flatlands of the North European Plain to the height of the Hall of Mirrors in Versailles and the Prussian-led declaration of German nationhood, Prussia endured – and ensured the transition from monastic state, to Kingdom, and then Empire.

Capable of instilling fear and bringing forth admiration in equal measure, it has been dubbed the Kingdom hatched from a cannonball, the state from the sandbox of the Holy Roman Empire, and widely recognised as being responsible for the accouchement of many of the characteristics and values that are now said to be distinctly Deutsch.

Prussia gave the world not just Germany; but German philosophers, artists, and academics.

Immanuel Kant was born and spent almost his entire life in the Prussian port city of Königsberg, revolutionary firebrand Karl Marx and philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche were both Prussian-born; the brothers Alexander and Wilhelm von Humboldt; the writers E. T. A. Hoffmann, Heinrich von Kleist, and Heinrich Heine. Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm, collectors of world-famous fairy tales, would call Prussia home. As would the composers Felix Mendelssohn, Robert Schumann, and Richard Strauss. The great Romantic painter Caspar David Friedrich (1774–1840) came from Greifswald in the Prussian province of Pomerania. Without Prussia, Johann Sebastian Bach’s Brandenburg Concertos would not exist.

Whether it be the legacy of its most celebrated leader, Frederick the Great, the legends of it abnormally tall soldiers, the cultural, scientific, and social achievements the state fostered, or the poisonously fierce patriotism and pernicious militarism its fiercest critics scorn – there is much still to say about Prussia.

–

Catholic Cowboys Of The Wild East

“A prince … is only the first servant of the state, who is obliged to act with probity and prudence. … As the sovereign is properly the head of a family of citizens, the father of his people, he ought on all occasions to be the last refuge of the unfortunate.”

Frederick II of Prussia

The many iterations of what – at its height – was known as the Imperial Kingdom of Prussia began in the north eastern outreaches of Europe, as the Teutonic Knights, a mediaeval military religious order, forcibly Christianised one of the last remaining pagan regions on the continent.

These Catholic crusaders would establish a monastic state, gradually Germanising the region through immigration from central and western Germanic lands.

The native Old Prussian tribes that had previously inhabited this region would be gradually assimilated by the 18th century when their language also became practically extinct.

The term Prussian – derived from the term Prūsas meaning ‘body of water’ – would, however, live on in the name given to the Duchy of Prussia that emerged following the decline of the Teutonic Order.

Such is the bloody irony of the period: that the Teutonic Knights would repress and destroy the culture and peoples of a land they would claim as their own. And then seeking a title for themselves, would name themselves after the region and people they have so violently subjugated.

By the 16th century, the stewardship of Prussia – sandwiched as it was between Poland, Sweden, and other regional powers – came into question. Accelerated by the gradual decline in the strength of the Teutonic Order.

Control of the duchy would be re-secured by Albert I, the head of the Teutonic Order, in 1525 only after pledging allegiance to the King of Poland – in what is often called the Prussian Homage.

Albert would also become the first European ruler to establish Lutheranism, and thus Protestantism, as the official state religion of his lands. This odd arrangement – a Protestant duchy owing fealty to Catholic Poland – set the stage for Prussia’s rise.

A member of the House of Hohenzollern royal family, Albert was a nephew of the Polish King, Sigismund I, and son of Frederick I, Margrave of Brandenburg-Ansbach. A significant connection that would play an important role in the development of Prussia.

At the time, Albert’s court was based in the city of Königsberg (now known as Kaliningrad and since 1945 a part of the Soviet Union and now the Russian Federation).

The shift to Berlin as the capital of Prussia would take another two centuries.

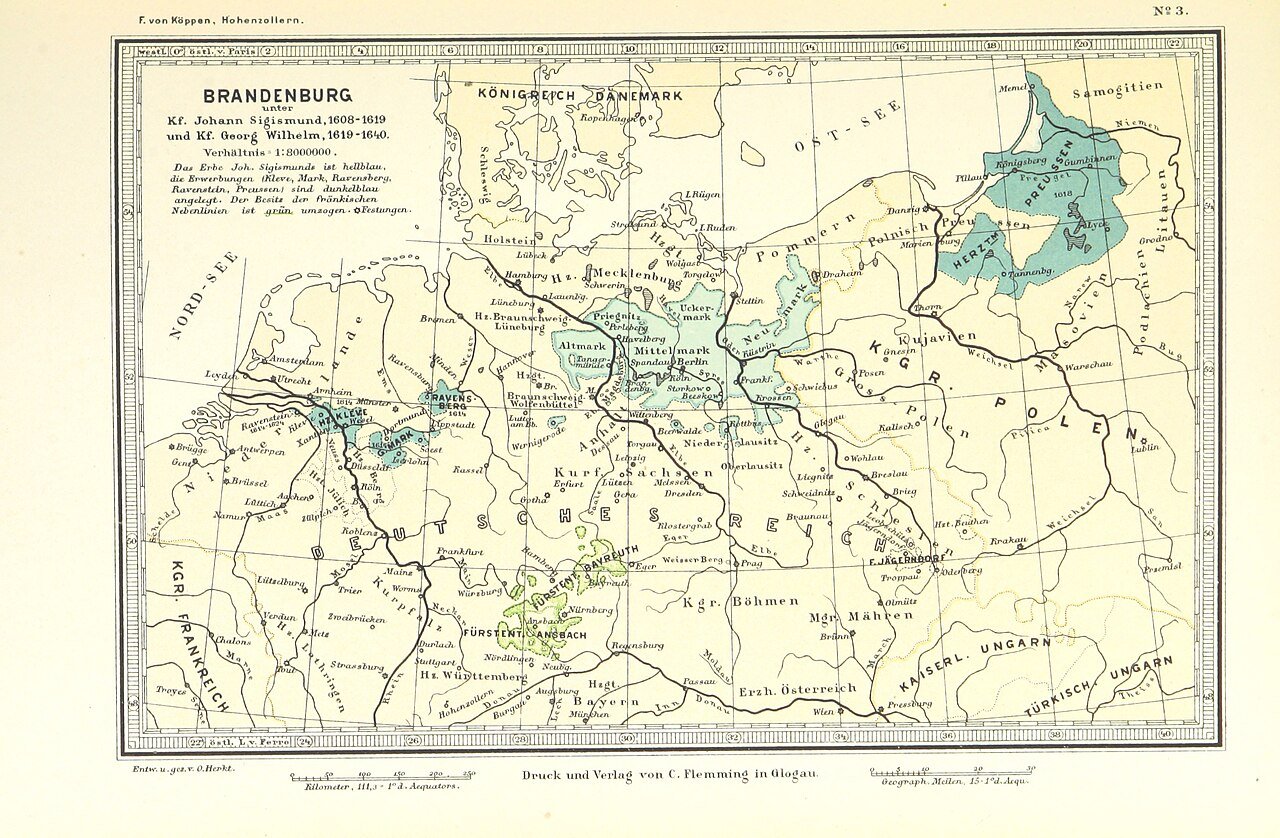

In 1618 the duchy fell into the hands of the Hohenzollern dynasty of Brandenburg, meaning one ambitious family now ruled both Brandenburg (a German electorate) and Prussia (a Polish fief).

Through marriage – and the extinction of the male line of succession in Prussia – the Electors of Brandenburg inherited full control of the Duchy of Prussia.

Establishing what was known as Brandenburg-Prussia.

Thus, by the 17th century, the “cowboys” of the Teutonic Order had given way to princely statesmen.

The union of Brandenburg and Prussia created a powerful Brandenburg-Prussia bloc, the nucleus from which a modern Protestant power would emerge.

It also planted the seed of German nationalism in the region – as Germanic culture and the Protestant faith took root in Prussia, the stage was set for this frontier land to identify itself with the wider German nation in the centuries to come.

Although, at the time, the resulting state still consisted of geographically disconnected territories in Prussia, Brandenburg, and the Rhineland lands of Cleves and Mark.

This, however, would soon change.

As historian Christopher Clarke would note: “the Baltic territory formerly known as Ducal Prussia was no longer a mere outlying possession of the Brandenburg heartland, but a constitutive element in the new royal-electoral amalgam that would first be known as Brandenburg-Prussia, later simply as Prussia.”

–

The Iron Kingdom

“I wish it were night or the Prussians would come!”

Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington, expecting to go into battle against Napoleon Bonaparte without his Prussian allies at the Battle of Waterloo

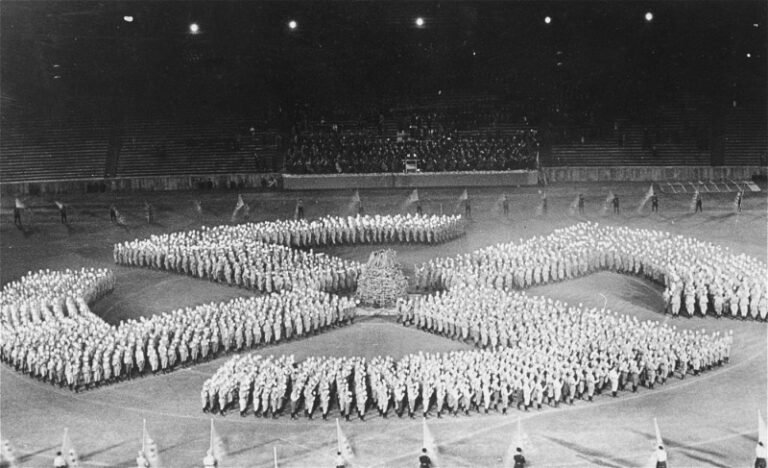

Prussia’s meteoric rise came in the 18th century, when it was forged into Europe’s “Iron Kingdom”. In 1701, the Hohenzollern ruler crowned himself King in Prussia, elevating the duchy to a kingdom even while much of its lands remained part of the Holy Roman Empire. From that point, Prussia cultivated a famously militaristic identity.

The state was poor in natural resources, but rich in military discipline – a discipline so pronounced that one contemporary quipped, “Prussia is not a country with an army, but an army with a country.”

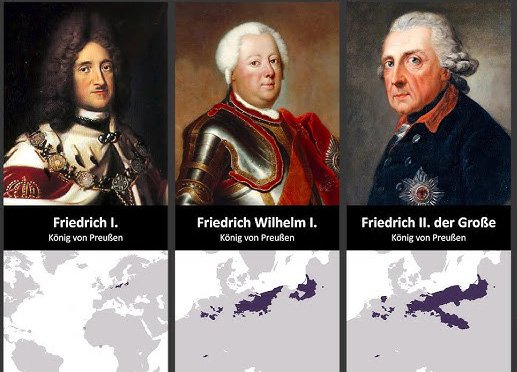

In-fact, the development of Prussia from this point would be intrinsically tied not only to the three successive monarchs of the 18th century (Fredrick I/Frederick William I/Frederick II) but also their distinctly different personalities.

- The first, Frederick I, would usher into existence the concept of a greater, more central Prussia.

- His son, Frederick I, known by his nickname ‘The Soldier King’, would place emphasis on the creation and training of a modern capable army.

- While his son, Frederick II (also known as Frederick the Great), would wield this power on the battlefield. Cementing Prussia’s reputation as a major European player and military power and also his personal legacy as one of the most capable military strategists in history.

As the first Prussian King would look outwards for recognition, the second would turn his gaze inwards – gutting his father’s court of any excess expenditure, instead focusing on the development of his army, the often sadistic pleasures of his Tobacco Ministry, where the King and his cabal would gather to gossip, drink, and torment each other in almost equal measure.

Frederick William I (the ‘Soldier-King’), turned the Prussian Army into Europe’s most efficient fighting force, with iron discipline instilled in both troops and society. Soldiers drilled relentlessly, bureaucracy was organized to serve the military, and even the tall grenadiers of Potsdam (hand-picked for height) became an object of legend. Prussia’s social structure was bent toward war: the Junker nobles provided the officer corps and peasants filled the ranks, all worshipping the cult of obedience.

Frederick II, now content with the structures and state (in particular, the military) that his predecessors had established, used this foundation to engage in independent Kingship.

Proclaiming himself King of Prussia, in a symbolic break from the hierarchy of the Holy Roman Empire, fighting wars against the French, Russian and Austria-Hungarian Empire – and emerging victorious.

Thanks as much to the army he had inherited from his father as his skills as a military tactician that would earn him the title: ‘Frederick the Great’.

While an incredibly superficial estimation of the successive monarchs and their achievements and merits, it does underline the important thread in this story.

In the space of less than 100 years, Prussia grew from a sandy backwater and Ducal Province in the North of Poland to a mighty power known around the world and respected as much as it was feared.

By the year of Frederick the Great’s death, Prussia’s territory had more than doubled and it was recognized as one of the continent’s leading states.

In time, Prussia would transform itself into a leading player in European politics, a highly regarded military power, and a great supporter of the arts and sciences.

Although it would be the state’s formidable professional army that would win it the most praise – and suspicion. With Prussia located in the centre of Europe, lacking in natural boundaries and surrounded by potential enemies, the state’s military was considered especially important to Prussia’s survival and growth – with the percussive march of Prussian soldiery perhaps the most defining aspect of its existence.

While its belligerence would be highlighted, Prussia would also serve as a safe haven for people fleeing religious persecution in much the same way that the United States welcomed immigrants seeking freedom in the 19th century.

Under King Friedrich II – who ruled from 1740 until 1786 – Berlin was transformed into the centre of Enlightenment thinking in the German speaking lands.

Remarkably, this tough warrior-king was also a patron of philosophy and the arts – he corresponded with Voltaire, played the flute, and promoted religious tolerance – exemplifying the paradox of Prussia’s legacy.

Prussia came to be seen as “Europe’s Sparta,” admired and feared for its martial prowess. Its army, with crack drill and rapid-fire musket volleys, became the envy (and dread) of larger nations. Yet Prussia also championed the Enlightenment in government, pioneering merit-based civil service, compulsory education, and legal reforms. It was this blend of “iron and reason” – ruthless military efficiency coupled with modern statecraft – that made the Prussian kingdom so influential.

The early years of Prussian state-building in the 17th century and consolidation of territory would set the stage for the projections of power and achievements of the Kingdom’s inhabitants in the following century.

By the early 19th century, Prussia’s rise was complete: it had helped defeat Napoleon, gained vast new territories (including the Rhineland), and stood poised to lead the German peoples into a new era.

Resulting in a capital city full of architecture inspired by the Greek and Roman civilisations that the Prussia elites sought to emulate, world-renowned institutions of learning, and a cultural milieu to rival that in Paris, Saint Petersburg, or London.

–

The Making Of Germany

“Prussia is not a state with an army, but an army with a state.”

French revolutionary Mirabeau

After Napoleon’s second defeat, the German states were loosely grouped in a confederation, with Prussia and its rival Austria competing for influence.

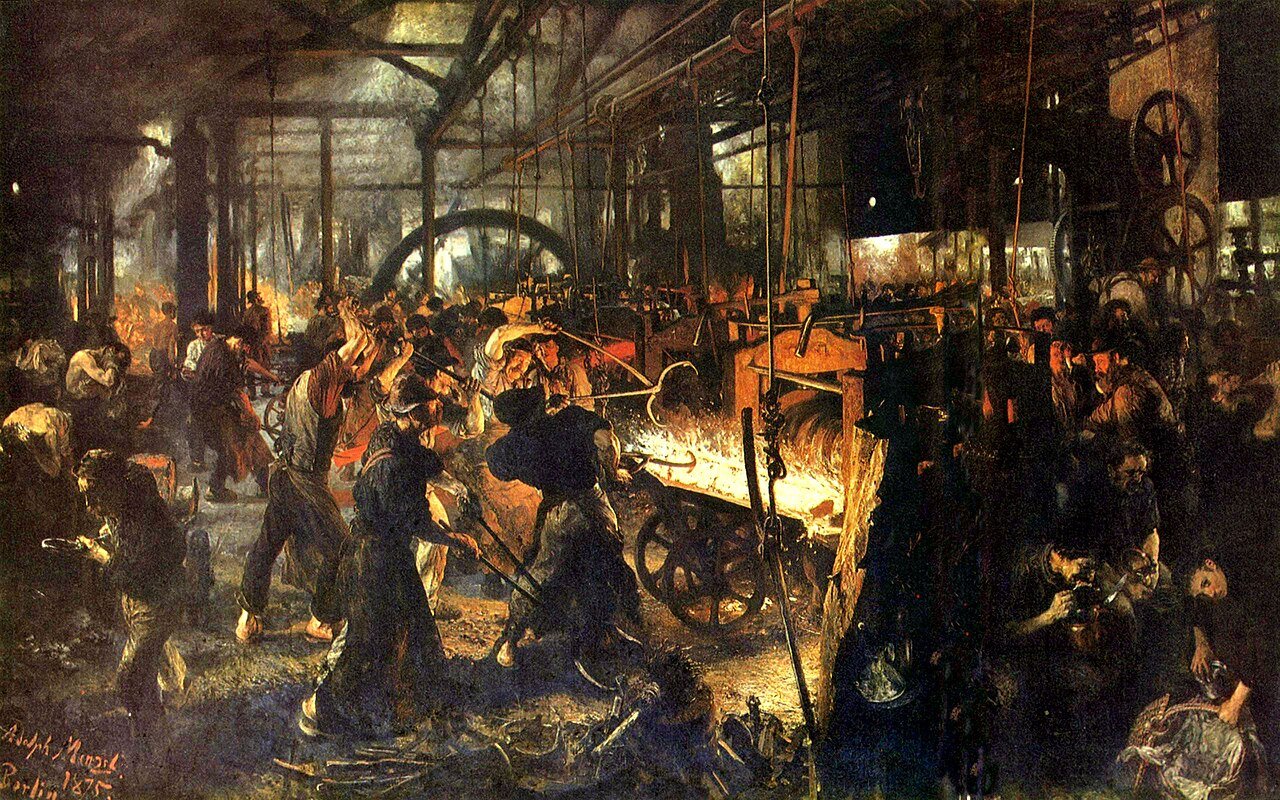

Prussia, industrializing rapidly in the west and reforming its army, positioned itself as the champion of German unity (on its own terms).

The 19th century saw Prussia become the architect of German unification – a development that would fundamentally reshape Europe. The task fell to the Iron Chancellor, Otto von Bismarck, a master of realpolitik. Appointed Prussian minister-president in 1862, Bismarck famously declared that the great questions of the age would be settled “by iron and blood.” He promptly set about using Prussia’s military might and diplomacy to achieve what liberal nationalists had failed to: a united Germany under Prussian leadership.

Bismarck’s strategy was to unify Germany through a series of short, decisive wars

- First, Prussia (in alliance with Austria) defeated Denmark in 1864, liberating the German-speaking duchies of Schleswig and Holstein.

- Next, in 1866, Bismarck deliberately provoked the Austro-Prussian War – a brief conflict in which Prussia’s well-oiled war machine crushed Austria in just seven weeks. This victory shocked Europe and ousted Austrian influence from German affairs. Prussia annexed several North German states and formed the North German Confederation under its hegemony.

- Finally, in 1870, Bismarck goaded France into attacking, igniting the Franco-Prussian War. Behind a facade of defending German honor, Prussia rallied the independent South German states to join the fight, and together they humiliated France at Sedan.

In the aftermath, in the glittering Hall of Mirrors at Versailles, King Wilhelm I of Prussia was proclaimed Emperor of a united Germany on January 18th 1871.

It was a Prussian triumph: the birth of the German Empire (Deutsches Kaiserreich) with Prussia at its core. Bismarck had achieved with cannons what centuries of princes and revolutionaries could not – Germany was now one nation-state.

This Prussia-led proclamation of the German Empire fell on the anniversary of the coronation of Frederick I in 1701. Emphasising the continuity in the succession of the crowning of the first Prussian King and the first German Emperor.

Prussian dominance set the tone in the new empire.

An Empire conjured into existence at the same time as Northern and Southern Italy were finally unified, a matter for which Prussia can also take a great measure of responsibility.

By the time of German Unification in 1871 – the Prussian lands made up around three-fifths of the territory of what would become known as Germany.

Amounting to around two-thirds of the population of this new mega-state.

With the Prussian capital of Berlin now the capital of the unified country and the Hohenzollern monarch both King of Prussia and German Emperor – Prussia’s König became Germany’s Kaiser.

Soon Prussian officials (like Bismarck) filled key governmental positions.

The empire’s values in many ways reflected Prussian militarism and conservatism, which created internal tensions. Southern German states, largely Catholic and more liberal, warily accepted rule by Protestant Prussia. Bismarck himself launched the Kulturkampf in the 1870s – a “culture struggle” against the Catholic Church – attempting to impose Protestant-prussian ideals, which only alienated Catholic citizens.

Moreover, Prussia’s authoritarian political culture (e.g. its three-class voting system and powerful aristocracy) left a democratic deficit in the Reich. While Germany industrialized and grew mighty, some wondered if the new state carried a “Prussian burden” – a legacy of rigid obedience and martial outlook that might cloud its future.

Nonetheless, there is no doubt that Prussia’s armies and statesmen made Germany.

The unification wars permanently altered Europe’s balance of power, and Prussia’s creation of the German Empire ushered in an era in which the new Germany – das Kaiserreich – would dominate the continent’s politics up until the First World War.

Naturally, Prussia would reap the benefits of its position, although now as a state – part of a country – rather than an independent power of its own.

That being said, Prussian dominance within the German state led many to conclude that Germany was simply an extension of Prussia power – by another name.

With the German loss of the First World War and the abdication of German Emperor Wilhelm II, Prussia was turned into a ‘Free State’. The German government seriously considered breaking up Prussia into smaller states, but eventually traditionalist sentiment prevailed and Prussia then became by far the largest state of the Weimar Republic.

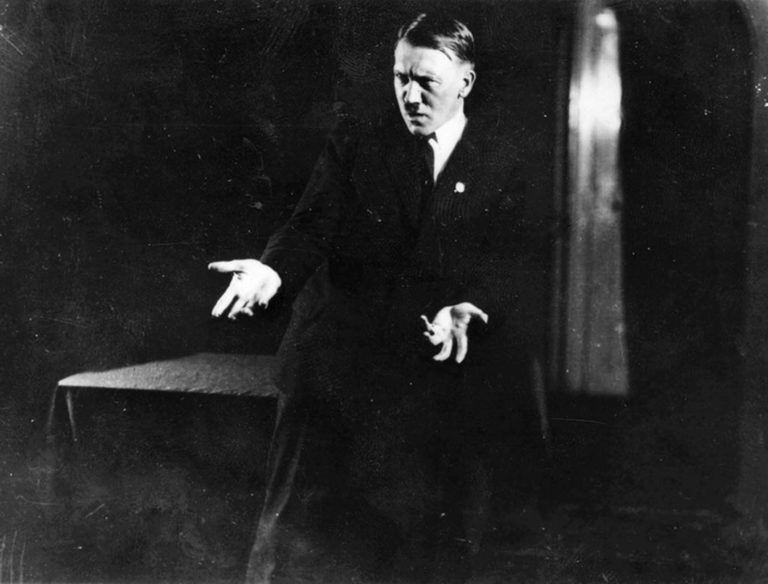

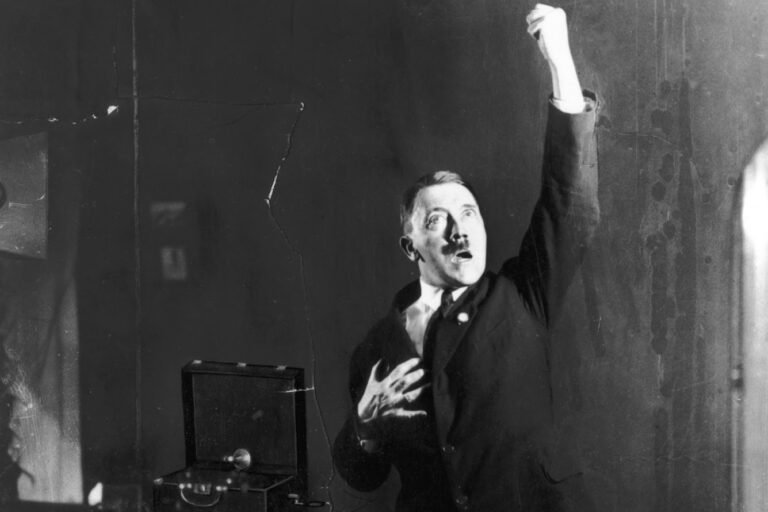

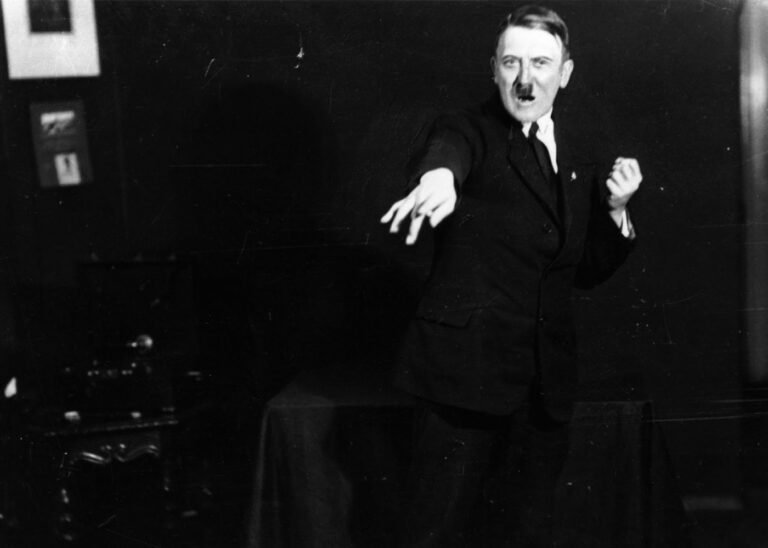

Two years after Adolf Hitler and the National Socialist Party seized control of Germany, the independence of the states within the country were abolished – in fact if not in law – as power became increasingly more centralised into the hands of the Nazi Party.

–

The Abolition of Prussia

“Of the two classes of Prussian officer, the bull-necked and the wasp-waisted, he belonged to the second. Monocled and effete in appearance, cold and distant in manner, he concentrated with such single-mindedness on his profession that when an aide, at the end of an all-night staff ride in East Prussia, pointed out to him the beauty of the river Pregel sparkling in the rising sun, the General gave a brief, hard look and replied, ‘An unimportant obstacle.”

Barbara Tuchman, The Guns of August

Prussia’s formidable reputation as Europe’s military drillmaster proved to be a double-edged sword.

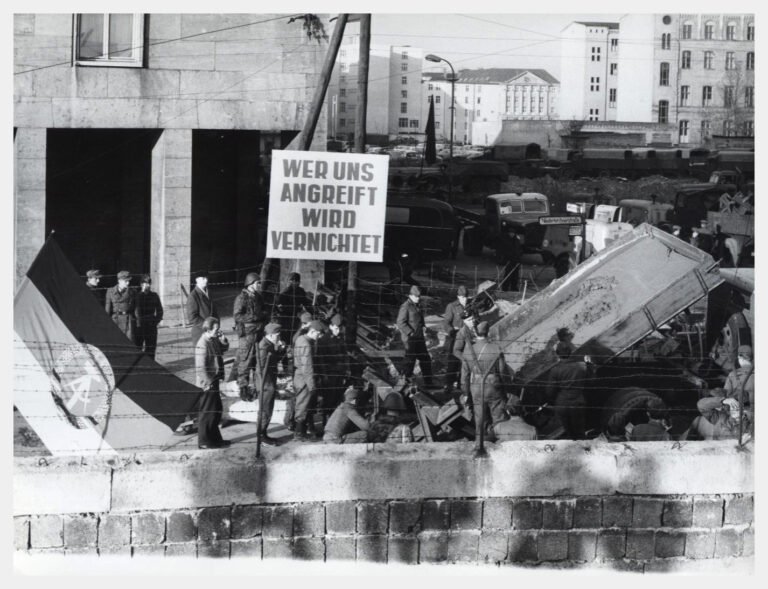

In the 20th century, after two devastating world wars, many came to blame the “Prussian spirit” for Germany’s militant nationalism.

Addressing the British Parliament on September 21st 1943, Prime Minister Winston Churchill said: “The core of Germany is Prussia… There is the source of the recurring pestilence”.

A sentiment echoed by many across Europe.

More than a mere seven letter word, Prussia had come to represent everything that was unforgivable about the Germany of the 20th century. Critics would claim to trace a clear path from the Thirty Years War to the Third Reich. The criminality of Nazi Germany reached back far into the Prussian past.

The idea took hold that Prussian militarism – with its exaltation of duty, hierarchy, and war – had paved the road to aggression and tragedy.

In 1945, as the Allies dismantled Hitler’s Third Reich, they also resolved to extinguish Prussia itself.

As historian Katja Hoyer, author of Blood and Iron, observed: “When the Allied victors of the Second World War decided to abolish Prussia as a German state in 1947, as if exercising a demon, they perpetuated the myth of the inevitability of the path from a Prussian-dominated Germany to Nazism.”

The once-mighty state had already been gutted: its heartlands in the east (East Prussia, Silesia, Pomerania) were occupied by Soviet and Polish forces and would soon be permanently severed from Germany.

But the Allies wanted a symbolic burial.

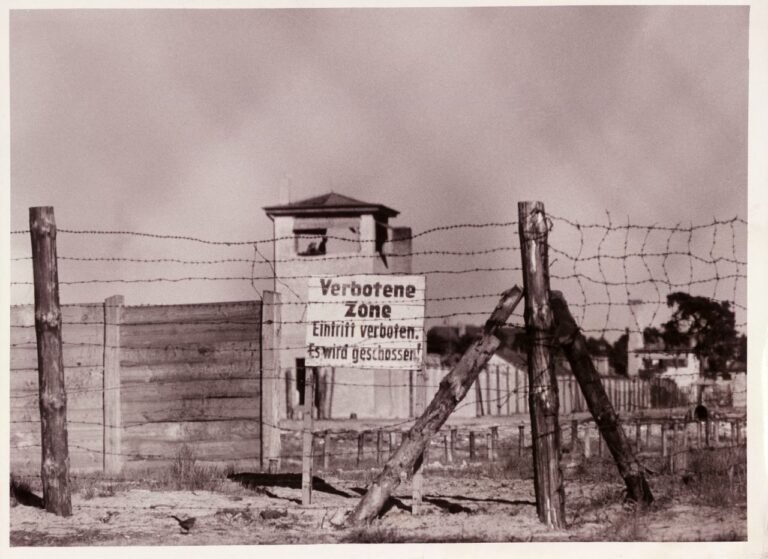

In February 1947, the Allied Control Council issued a blunt decree. “The Prussian State, which from early days has been a bearer of militarism and reaction in Germany, has de facto ceased to exist,” it declared, formally abolishing Prussia forever.

The Prussian government and its remaining institutions were dissolved and its territories reorganized into new administrative units.

After roughly 700 years, the name of Prussia was erased from the map.

This act was as much psychological as political – a conscious effort to break what was seen as the militaristic tradition of Prussianism. The Allies believed that by uprooting Prussia, they could ensure Germany would never again threaten world peace.

In reality, Prussia’s legacy is more complex than just spiked helmets and goose-steps. Historians note that Prussia also stood for efficient governance, education, and even enlightened values at times. The same Prussia that bred a stern officer corps also produced innovators in law, philosophy, and music. As Cambridge historian Christopher Clark has argued, Prussia was “far more complex” than the caricature – it had been “an exemplar of the European humanistic tradition, boasting a formidable government administration, an incorruptible civil service, and religious tolerance” alongside its military heritage.

Nevertheless, in 1947 the verdict was rendered: Prussia was to be no more.

Today, Prussia survives only in dusty history books and cultural memory.

Its former lands are divided among modern Germany, Poland, Russia, and others – a fragmented reminder of a once-unifying power.

The black eagle that once adorned Prussian flags is now a historical emblem rather than a national standard.

The German federal eagle that is featured on the wall of the Bundestag earned itself the nickname: “the fat duck”. A more disarming character.

Yet Prussia’s lingering legacy can still be felt.

When people speak of German efficiency, discipline, or even the iconic Pickelhaube helmet, they are echoing the memory of Prussia.

In the end, Prussia was a creature of its time – rising through iron and blood, shaping a nation, and then perishing in fire and rubble.

It left behind a unified Germany and a complicated reputation.

As one might say, Prussia’s body was destroyed, but its ghost lives on – in Germany’s national story, in European geopolitics, and in the cautionary tales of how power and militarism can shape history for both good and ill.

**

Conclusion

Prussia was not simply “Russia with a P,” but a distinct historic state and region that played a pivotal role in German history. Over the centuries, the term “Prussia” has referred to several entities.

- The first was the land of the pagan Prussians on the Baltic coast, conquered in the Middle Ages by German crusaders.

- The second was the powerful Kingdom of Prussia ruled by the Hohenzollern dynasty from 1701, which expanded to dominate northern Germany and lead German unification in 1871.

- The third was the Free State of Prussia after 1918, a state within Weimar Germany that was subsumed by the Nazis and ultimately abolished by the Allies in 1947.

In short, Prussia evolved from a medieval frontier conquest into the driving force behind a unified German Empire.

It is often remembered for its militarism and discipline, yet it also contributed administrative efficiency and enlightened reforms to European history.

***

If you’ve enjoyed reading this article, consider booking one of our private guided tours of Berlin.

HISTORICAL ARTICLES

Mythbusting Berlin

Are There Any Nazi Statues Left In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

Visitors to Berlin often arrive expecting to find the physical remnants of the tyranny of the 20th century still standing – statues of dictators, triumphal arches, or bronze idols. Instead, they often find none. The stone symbols and statues of the Third Reich are still gazing down on them, however, hiding in plain sight. But why are there no statues of Hitler? Did the Allies destroy them all in 1945, or is the truth stranger

Could The Western Allies Have Captured Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

To contemplate a Western Allied capture of Berlin in 1945 is to challenge the established endgame of the Second World War. What was the true military and logistical feasibility of a Western Allied assault on the Nazi capital? What factors truly sealed Berlin’s fate, and what might have changed had the Allies pushed eastward?

Answering these questions means delving into the complex interplay of logistics, political maneuvering, and the competing visions for a post-war world

Did Any Of The Rothschild Dynasty Die In The Holocaust? – Mythbusting Berlin

The Rothschild name is synonymous with immense wealth, influence, and persistent conspiracy theories—especially during the era of Nazi Germany. Often targeted by antisemitic propaganda, the family’s survival during World War II has sparked myths about their supposed immunity from Nazi persecution. But did any Rothschild family member actually perish in the Holocaust? This article explores that compelling question, unraveling historical misconceptions and revealing the reality behind one of Europe’s most famous dynasties.

Did Frederick The Great Introduce The Potato To Germany? – Mythbusting Berlin

One of the more bizarre claims to fame attributed to the first King of Prussia is that the man who would go down in history known as Frederick the Great introduced the potato to Germany during his reign back in the 1700s. This starchy root vegetable has undoubtedly become a staple part of German cuisine – an essential addition to any plate of Schnitzel, Schweinshaxn, and Königsberger Klopse – however, whether Frederick the Great is

Did Hitler Escape To Argentina In 1945? – Mythbusting Berlin

Although Nazi leader, Adolf Hitler, certainly remains an inescapable figure, could there be any truth to the story of his escape to Argentina in 1945? That the most wanted man on earth could simply vanish, to spend the rest of his life peacefully in South American obscurity captivates imaginations. Yet, despite numerous investigations, this tale persists primarily as myth—fueled by speculation, hearsay, and conspiracy theories.

Did Hugo Boss Design The Nazi Uniforms? – Mythbusting Berlin

The idea that Hugo Boss – the man whose name now adorns expensive suits and fragrances – was the creative genius behind the Nazi uniforms suggests a terrifying collision of haute couture and holocaust – a marriage of high style and high crimes. The image is striking: a German tailor sketching the ultimate villain’s costume. But history, as usual, is far messier, more bureaucratic, and more banal than the internet memes suggest. To understand who

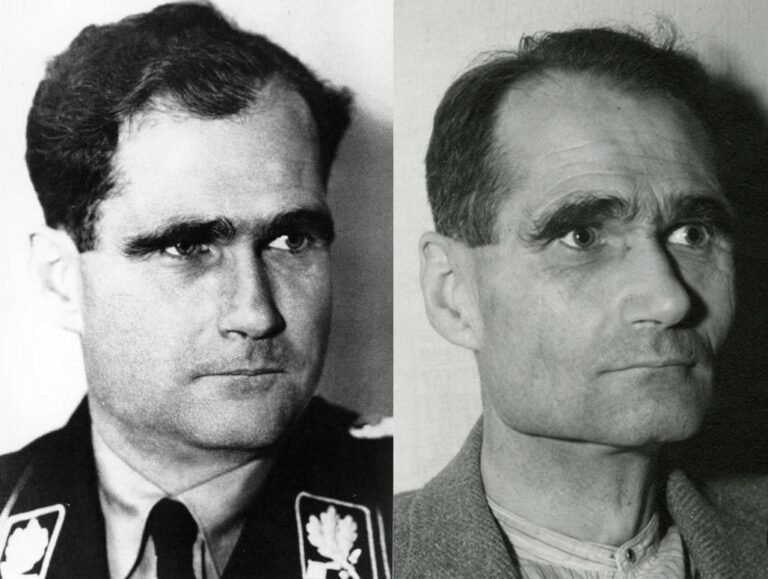

Did Rudolf Hess Really Commit Suicide? – Mythbusting Berlin

On a summer’s day in 1987, the last Nazi war criminal of the Nuremberg trials was found dead in a prison built for hundreds, yet for two decades, housed only him. The official verdict was suicide, a straightforward end to a life defined by fanaticism, delusion, and contradiction.

But the simplicity of the report belied the complexity of the man and the 46 years he had spent in Allied custody. In the meticulously controlled

Did The Nazis Develop Nuclear Weapons? – Mythbusting Berlin

The Nazi obsession with super-weapons became so serious in the closing stages of the Second World that Adolf Hitler personally believed that such ‘Wunderwaffen’ both existed in a usable form – and would save the country from defeat. Had the Nazis managed to develop nuclear weapons by 1945 – the outcome of the war would surely have been different. But how close were Hitler, Himmler, and his henchmen to developing an A-bomb?

Did The Nazis Invent Decaf Coffee? – Mythbusting Berlin

Persistent rumors claim that Nazis preferred their coffee anything but pure, leading some to wonder if they might have influenced the development of decaffeinated coffee. Although decaf was already widely available across Europe by the mid-20th century, speculation continues: could the Nazis really have played a role in popularizing—or even discovering—this caffeine-free alternative, or is this simply another caffeinated conspiracy cooked up to sensationalize an ordinary historical detail?

Did The Nazis Invent The Bicycle Reflector? – Mythbusting Berlin

The fruits of wartime ingenuity are plenty – so many, in-fact, that it has become somewhat of a worn cliche that as the guns start firing the innovators get to work, often solving problems while providing more problems for the enemy to overcome.The kind of progress that results in the production of newer improved, more lethal weapons, such as to increase the chances of victory.

Did The Nazis Run The Largest Counterfeiting Operation In History? – Mythbusting Berlin

During the Second World War the Nazis masterminded an astonishing plot to destabilise Britain by flooding its economy with counterfeit banknotes. Crafted in secret by concentration camp prisoners, this forged fortune became the most ambitious counterfeiting operation ever attempted. But was it history’s largest? Dive into the extraordinary tale of Operation Bernhard,

rife with deception, survival, and intrigue—revealing the truth behind one of the Third Reich’s most audacious schemes and its surprising legacy.

Did The Second World War End In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

When is a war ever truly over? When the last shot is fired in anger would seem like the best measure. Rarely, though, is it possible to gain insight into such a moment.

Remarkably, a record still exists of such a moment at the end of the First World War on the Western Front. A seismic register and recording of the last belching battery of British guns firing artillery across no-man’s-land, followed by a profound

Did The Spanish Flu Pandemic Help The Nazis Take Power? – Mythbusting Berlin

The devastating Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918-1919 struck amid Germany’s post-war turmoil, compounding social instability, economic hardship, and widespread political disillusionment. Could this catastrophic health crisis have indirectly paved the way for Nazi ascension? While often overshadowed by war and revolution, the pandemic’s profound psychological and societal impacts arguably contributed to the perfect storm, enabling extremist ideologies—including Nazism—to gain popularity and ultimately seize power in a fractured Germany.

Have Adolf Hitler’s Remains Been DNA Tested? – Mythbusting Berlin

In the smouldering ruins of Berlin in 1945, the world’s most wanted man vanished. Did Adolf Hitler, as official history attests, die by his own hand in the Führerbunker? Or did he escape, fuelling a thousand conspiracy theories that have echoed for decades? For years, the Soviets claimed to hold the gruesome proof of his death: a skull fragment and a set of teeth, locked away in Moscow archives. But in an age of definitive

How Did The Nazi Concentration Camps Differ From The Soviet GULAG?

The Nazi concentration camps and Soviet Gulag system have often been conflated in popular imagination—twin symbols of twentieth-century totalitarian horror. Yet the two systems operated on fundamentally different principles. One extracted labor to fuel industrialisation while accepting mass death as collateral damage; the other evolved into purpose-built machinery of genocide. Understanding these distinctions isn’t merely academic—it reveals how different ideologies produce different atrocities, and why Germany and Russia reckon with these legacies so differently today.

How Long Did It Take To Build The Berlin Wall? – Mythbusting Berlin

It is one of the most enduring images of the 20th century: a city divided overnight. The popular narrative tells us that Berliners went to sleep in a unified city and woke up in a prison. While the shock of August 13th 1961, was very real, the idea that the ‘Wall’ appeared instantly is a historical illusion. The physical scar that bisected Berlin was not a static creation, but a living, malevolent beast that evolved

How Many Assassination Attempts On Adolf Hitler Were There? – Mythbusting Berlin

Nazi leader, Adolf Hitler, projected an aura of invincibility, a man of destiny shielded by providence. But behind the carefully constructed image of the untouchable Führer lies a story of constant threat, of bombs that failed to detonate, and errant bullets that missed their mark. Unearth the hidden history of the numerous attempts on Hitler’s life as we explore the courage of those who tried to change the course of history and the devil’s luck

How Many Jews Died In The Holocaust? – Mythbusting Berlin

The answer to the question posed of how many Jews died in the Holocaust is a simple one: too many. That merely one death was an unforgivable obscenity is a fundamental and necessary realisation in understanding the capriciousness of this unparalleled racial genocide. To comprehend, however, the full number of Jews murdered in Europe by the Nazi regime in the 1930s and 1940s is a detective story of epic proportions: the evidence overwhelming, multifaceted, and

How Many People Died Trying To Escape East Germany? – Mythbusting Berlin

The image of the Berlin Wall is seared into our collective memory, a concrete symbol of Cold War oppression. We think of the daring escapes and the tragic deaths of those who failed. But that well-known number is only a fraction of the truth. The story of those who died trying to escape East Germany is far broader and more complex than most imagine, stretching along a thousand-kilometer border and out into the cold waters

How Old Is Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

A relatively new arrival in Europe, Berlin is over 1000 years younger than London, nevermind Rome or Athens, Jerusalem or Jericho. Just how old is Berlin though?

A question fraught with false assumptions and distortions – that has more often than not been answered with propaganda as it has with the cold hard truth.

Was Adolf Hitler A Drug Addict? – Mythbusting Berlin

Solving the enigma of the ‘Führer’ has become a preoccupation for many, since the arrival of the Austrian-German onto the world stage – although moving beyond the mythology without falling into the trap of prejudically extrapolating on the psychopathography of Hitler or demonising so as to excuse his actions has proven problematic. What to make of the man who became more than the sum of his masks? The painter; the military dilettante, the mass murderer,

Was Adolf Hitler A Freemason? – Mythbusting Berlin

History abhors a vacuum, but adores a mystery. Such is the speculative fiction suggesting a secret allegiance behind the rise of the Third Reich – that the catastrophe of the Second World War was orchestrated from the shadows of a Masonic lodge. The image of Adolf Hitler—the drifter from Vienna turned dictator—as a covert initiate of the very brotherhood he publicly reviled, however, creates a paradox that collapses under scrutiny. As when we unlock the

Was Adolf Hitler Gay? – Mythbusting Berlin

In the shadowy corridors of Third Reich history, few questions provoke as much tabloid curiosity and scholarly exasperation as the sexuality of Adolf Hitler. For decades, rumors have swirled—whispered by political enemies in 1930s Munich, psychoanalyzed by American spies in the 1940s, and sensationalized by revisionist authors today. Was the dictator who condemned thousands of men to concentration camps for “deviant” behavior hiding a secret of his own? By peeling back the layers of propaganda,

Was Adolf Hitler Jewish? – Mythbusting Berlin

Was the dictator who orchestrated the murder of millions of European Jews secretly one of them? It is perhaps the darkest irony imaginable, a story whispered for decades in backrooms, bars, and conspiracy forums alike. The most-common rumour – the ‘Frankenberger Myth’ – suggests that Adolf Hitler’s paternal grandfather was Jewish, a secret so damaging it could have unraveled the entire Nazi regime. But where does this claim come from? And, more importantly, is there

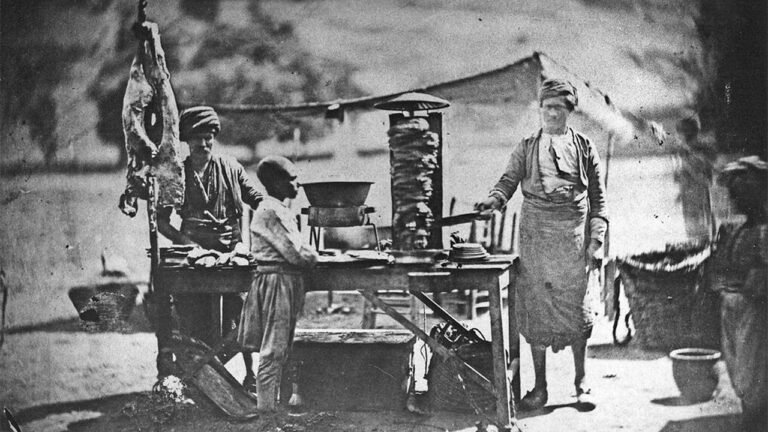

Was Currywurst Invented In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

Explore the story behind what many consider Berlin’s most iconic snack—the ever-so-humble Currywurst. Often hailed as an enduring symbol of culinary creativity amid Cold War scarcity, this humble dish has inspired fierce debate about its true origin. But was it genuinely invented here in Berlin, or have proud locals simply adopted and elevated this spicy street-food favorite into legendary status all their own?

Was Fanta Invented By The Nazis? – Mythbusting Berlin

As one of the most secretive organisations in the world, the Coca Cola corporation refuses to share its secret recipe with anyone. Famously insisting only on shipping the base syrup of its drinks to plants around the world to be carbonated and distributed.

This combined with the trade limitations of the Second World War may have led to the introduction of one of the most popular soft-drinks in the world. But could it be true:

Was Frederick The Great Gay? – Mythbusting Berlin

Frederick II of Prussia, better known as Frederick the Great, is often remembered as the archetypal enlightened monarch – a brilliant military commander, patron of the arts, and learned philosopher. Yet behind the stern portraits of this 18th-century warrior-king lies a personal life long shrouded in intrigue and speculation. Intrigue around the king’s sexual orientation has persisted through the centuries, chiefly revolving around one question: Was Frederick the Great gay?

Was Henry Ford A Nazi? – Mythbusting Berlin

US auto tycoon, Henry Ford, holds the ignominious distinction of being the only American Adolf Hitler praised by name in his National Socialist manifesto: ‘Mein Kampf’. This was not, as it turns out, the only connection between Ford and the Party of Hitler, Himmler, and the Holocaust.

Ford’s overt affinity with the Third Reich reveals a troubling past. How deep these connections ran, and how consequential they were for both sides, is a chapter

Was The Colour Blue Invented In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

Tracing the true history of blue—from ancient Egyptian dyes to the accidental discovery of Prussian Blue in a Berlin lab. We’ll debunk myths about seeing blue, explore colonial indigo plantations, scale mountains with a cyanometer, and trace Van Gogh’s starry skies—all to answer one question: how did Berlin shape our understanding of the world’s rarest color?

Was The Döner Kebab Invented In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

Unlikely icon of immigrant success; fast food symbol of the working class; over-hyped midnight disco eat; or culturally appropriated cuisine? Its influence goes far beyond layers of seasoned meat and fresh vegetables stuffed into pita bread. But does Berlin deserve credit as the Döner Kebab’s true birthplace, or has the city merely refined and popularized a culinary tradition imported from elsewhere?

Was The Fall Of The Berlin Wall An Accident? – Mythbusting Berlin

On a seasonally crisp night in November 1989, one of the most astonishing events of the 20th century occurred. After twenty eight years, three months, and twenty eight days of defining and dividing the German capital, the Berlin Wall ceased to exist – at least in an abstract sense. Although the removal of this symbol of the failure of the East German system would take some time, its purpose – as a border fortification erected

Was The Nazi Party Democratically Elected? – Mythbusting Berlin

The myth persists that Adolf Hitler rose to power through popular democratic choice. Yet history reveals a darker, more complicated truth. Hitler’s ascent involved exploiting democratic institutions, orchestrating violence, propaganda, and political intrigue—not a simple election victory. Understanding how Germany’s democracy collapsed into dictatorship helps illuminate the dangerous interplay between public desperation, elite miscalculations, and extremist ambition, providing crucial lessons for safeguarding democracy today.

Were The Allied Bombings Of Germany War Crimes? – Mythbusting Berlin

The history of the Allied bombing of Germany during the Second World War still triggers fierce debate. Was reducing cities to rubble a necessary evil – justice from above in a just war – or an unforgivable crime? Can the intentional targeting of civilians ever be justified as militarily necessary?

In a conflict where all rules seemed to vanish, an even more pertinent question persists: by the very standards they would use to judge their

Were The Nazi Medical Experiments Useful? – Mythbusting Berlin

Before the Nazi period, German medicine was considered the envy of the world – a shining monument to progress. But deep within that monument, a rot was spreading, one which would collapse the entire structure into an abattoir. From the wreckage, we are left with a profoundly uncomfortable inheritance: a moral enigma wrapped in doctor’s whites.

What to make of the data, the images, and the terrible knowledge gleaned from unimaginable human suffering. Whether

What Are The Origins Of The Nazi Salute? – Mythbusting Berlin

A specter is haunting the modern mind, a gesture so charged with the dark electricity of history that its mere depiction can unleash a storm of controversy.

It is a simple movement: the right arm, stiff and straight, raised to the sky. But in that simplicity lies a terrifying power, a symbol of a regime that plunged the world into an abyss and a chilling reminder of humanity’s capacity for organised hatred.

This

What Are The Origins Of The Nazi Swastika? – Mythbusting Berlin

Long before the legions of the Third Reich marched beneath its stark, unnerving geometry, the swastika lived a thousand different lives. It was a symbol of breathtaking antiquity, a globetrotting emblem of hope and good fortune that found a home in the most disparate of cultures. To even begin to understand its dark 20th-century incarnation, one must first journey back, not centuries, but millennia.

What Are The Pink Pipes In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

A first-time visitor to Berlin could be forgiven for thinking the city is in the midst of a bizarre art installation. Bright pink pipes, thick as an elephant’s leg, climb out of the ground, snake over pavements, arch across roads, and disappear back into the earth. Are they part of a complex gas network? A postmodern artistic statement? A whimsical navigation system? These theories, all logical, are all wrong. The truth is far more elemental,

What Do The Colours Of The German Flag Symbolise? – Mythbusting Berlin

What does a flag mean? Is it merely a coloured cloth, or does it hold the hopes, struggles, and identity of a nation? The German flag, with its bold stripes of black, red, and gold, is instantly recognisable. But the story of its colours is a tumultuous journey through revolution, suppression, and reinvention. The common explanation for their symbolism is a simple, romantic verse, yet the truth is a far more complex and contested tale,

What Happened To Adolf Hitler’s Alligator? – Mythbusting Berlin

It is often said that you can tell a lot about a person by their relationship with animals; that owners often come to look and behave like their pets. Or is it perhaps more that people choose their pets to correspond to their personality? Nazi leader Adolf Hitler’s love of dogs, for example, is well documented but what is there to make of his relationship with reptiles?

What Happenened To The German Royal Family? – Mythbusting Berlin

When the smoke cleared over the trenches in November 1918, the German Empire had evaporated, and with it, the divine right of the Hohenzollern dynasty. Conventional wisdom suggests the family simply vanished into the sepia-toned obscurity of history books—exiled, forgotten, and irrelevant. But dynasties, like weeds in a landscaped garden, are notoriously difficult to uproot entirely. The story of the German royals did not end with the Kaiser’s flight to Holland; it merely shifted gears.

What Is The Difference Between Fascism & Nazism? – Mythbusting Berlin

While the terms ‘Fascist’ and ‘Nazi’ are often bandied around interchangeably as shorthand for tyranny – Italian fascism and German National Socialism were distinctly different beasts. Albeit ideological kin. One an ideology of state-worship, born from post-war chaos and national pride; the other built upon a fanatical, pseudo-scientific obsession with race. Two peas in the same totalitarian pod – twins in tyranny – more succinctly summarised as the Nazi chicken to the Fascist egg.

What Was Checkpoint Charlie? – Mythbusting Berlin

Checkpoint Charlie remains among Berlin’s most visited historical sites, famed worldwide for its significance during the Cold War. Originally established as a modest border-crossing point, it evolved dramatically over the decades into an international symbol of freedom, espionage, and intrigue. Today, critics and locals often dismiss it as little more than a tourist trap—Berlin’s Disneyland—but how exactly did Checkpoint Charlie get its peculiar name, and what truths hide behind its popularity?

What Was Prussia? – Mythbusting Berlin

Prussia’s legacy is both remarkable and contentious—once a minor duchy, it rose dramatically to shape modern European history. Renowned for military discipline, administrative efficiency, and cultural sophistication, Prussia was instrumental in uniting the German states, laying foundations for a unified Germany. But how did this kingdom, with its roots in Baltic territories, achieve such prominence, and why does its complex history continue to evoke admiration, debate, and occasional discomfort in Germany today?

What Was The Berlin Airlift? – Mythbusting Berlin

In the ruins of 1948, the silence of Berlin was not a sign of peace, but a held breath before a new catastrophe. The city, drowning in rubble and political intrigue, became the staging ground for the twentieth century’s most audacious gamble. While popular history remembers the chocolate parachutes and smiling pilots, the reality of the Berlin Airlift was a terrifying operational nightmare born from a ruthless currency war. It wasn’t just a humanitarian mission;

What Was The Socialist Kiss? – Mythbusting Berlin

It is one of the most curious and enduring images of the Cold War: two middle-aged, grey-suited men, locked in a fervent embrace, their lips pressed together in a kiss of apparent revolutionary passion. This was the ‘Socialist Fraternal Kiss’, a ritual that, for a time, seemed to encapsulate the unwavering solidarity of the Eastern Bloc.

But what was behind this seemingly intimate gesture? Was it a genuine expression of camaraderie, a piece of

Who Built The Berlin Wall? – Mythbusting Berlin

One of the most common questions I have encountered from people curious about Berlin, and often so cryptically phrased. Who built the Berlin Wall? A simple five-word query, yet one that can be read one of two ways. More than thirty years since the ‘Fall of the Wall’, the story of its construction continues to baffle many who are mainly familiar with its existence through knowledge of its importance…

Who Really Raised The Soviet Flag On The Reichstag? – Mythbusting Berlin

One iconic photograph has come to symbolise the Red Army’s victory over Nazi Germany in 1945—the Soviet flag waving triumphantly above Berlin’s battered Reichstag building. Yet behind this enduring image lies controversy, confusion, and political manipulation. Who truly raised the Soviet banner atop the Reichstag? Was it a spontaneous act of heroism or carefully staged Soviet propaganda? Decades later, unraveling the truth reveals surprising layers beneath the mythologized symbol of Soviet triumph.

Who Was Really Responsible For The Reichstag Fire? – Mythbusting Berlin

Various theories have been posited as to who actually set fire to the German parliament in 1933. Was it the opening act in an attempted Communist coup or a calculated false flag operation carried out by elements of the Nazi Party, intended to create the conditions necessary for introducing single-party rule? And what part did the young man from Holland, arrested shirtless inside the building the night of the fire, play in this event?

Who Were The Last Nazis On Trial? – Mythbusting Berlin

More than eighty years after the Holocaust, courtrooms across Germany still echo with testimony from the final chapter of Nazi justice. Centenarian defendants in wheelchairs, their faces hidden behind folders, arrive to answer for crimes committed in their youth. These are not the architects of genocide—those men faced their reckoning at Nuremberg decades ago. These are the guards, the secretaries, the bookkeepers: ordinary people who enabled extraordinary evil. Their trials represent a legal revolution: the

Why Is Berlin The Capital Of Germany? – Mythbusting Berlin

There was little in its humble origins—as a twin trading outpost on a minor European river—to suggest that Berlin was destined for greatness. It sits on the flat expanse of the North European Plain, a landscape once dismissively referred to as the “sandbox of the Holy Roman Empire.” Unlike other world capitals, it lacks breathtaking scenery or a naturally defensible position. It is a city built not on majestic hills or a grand harbour, but