“Under the Nazis, I was a ‘political’. I knew I had an enemy. Under the Soviets, I was a ‘socially dangerous element’. It was like fighting fog.”

Margarete Buber-Neumann, prisoner of Stalin & Hitler

In the winter of 1940, on a windswept bridge spanning the River Bug at Brest-Litovsk, Margarete Buber-Neumann walked from one nightmare into another.

She was a German Communist who had fled to Moscow to escape Hitler, only to be swallowed by Stalin’s terror and sent to a labour camp in Kazakhstan.

Now, in a grotesque gesture of alliance under the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, Stalin was handing her back to the Nazis.

She had survived the starvation and lice of the Gulag, only to be immediately thrown into the Ravensbrück concentration camp by the SS. She became history’s unwilling control group—a rare witness who looked into the eyes of both monsters and survived to tell the difference.

Her eventual conclusion in her memoir, ‘Under Two Dictators’, was chilling: while the methods varied, the disregard for human life was identical.

While Buber-Neumann provided the comparative anatomy of these systems, it was others who mapped their distinct souls for the public.

On the Nazi side, the chemist Primo Levi dissected the ‘Grey Zone’ of Auschwitz, alongside Elie Wiesel – survivor of Buchenwald and Auschwitz – whose ‘Night’ gave a voice to the spiritual void of the Holocaust.

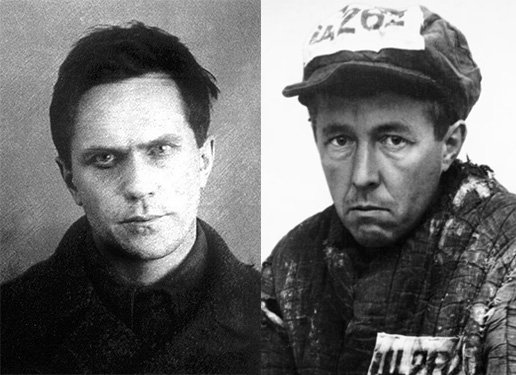

Facing them from the frozen east were Varlam Shalamov, whose ‘Kolyma Tales’ captured the radioactive effect of the GULAG on the human spirit, and Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, the archivist who compiled the screaming testimony of the entire Archipelago.

Through the lens of Buber-Neumann’s unique journey and the writings of these titans, we can at least hope to come close to better comprehend the function – the theory and practice of hell – in these penal facilities.

But to understand how a prison cell transformed from a holding pen into a slave labour pool and factory for death, we cannot start in 1940.

We must travel much further back—to an Athenian prison cell in 399 BC, where an old philosopher sat calmly, awaiting a cup of hemlock.

–

The Long Shadow Of Punishment

“Roman law only allowed the use of prisons for preventive custody, a stage in processing criminals before trial or execution… punitive imprisonment [was] an illegal deviation from an ideal model of punishment.”

Theodor Mommsen, Römisches Strafrecht (1899)

The ancient world had prisons, but it did not have imprisonment.

This distinction may seem pedantic until you realize it explains why the Greek philosopher, Socrates, spent his final month in an Athenian jail yet died for a crime that carried no prison sentence. His cell near the Agora—archaeologists have likely identified it by the peculiar discovery of thirteen small clay medicine bottles, each containing individually measured doses of hemlock held him only until his actual punishment could be administered.

Going to prison was not the penalty. Death was.

The Romans codified this principle.

The jurist Ulpian (c.170-223AD) declared prisons should be used “ad continendos homines non ad puniendos”—for holding men, not punishing them.

Rome’s most infamous prison, the Mamertine (known as the Tullianum), stood beneath the Capitoline Hill as a waiting room for execution, not a destination in itself.

Jugurtha, King of Numidia, starved to death there.

Vercingetorix, the Gallic chieftain who dared resist Caesar, was paraded in triumph before being strangled in its circular lower dungeon.

The historian Sallust described this place as “hideous and fearsome to behold”—twelve feet underground, enclosed by walls and a vaulted ceiling of stone, reeking of neglect and darkness.

For over a millennium, this remained the paradigm.

Medieval castle dungeons—the word derives from donjon, the keep’s central tower—held prisoners awaiting trial, ransom, or the executioner’s attention.

The transformation into prolonged imprisonment for its own sake began with an unlikely source: the Church.

Monastic prisons pioneered the concept of confinement for penance—solitary cells where wayward monks might reconnect with God.

The very word ‘penitentiary’ preserves this origin.

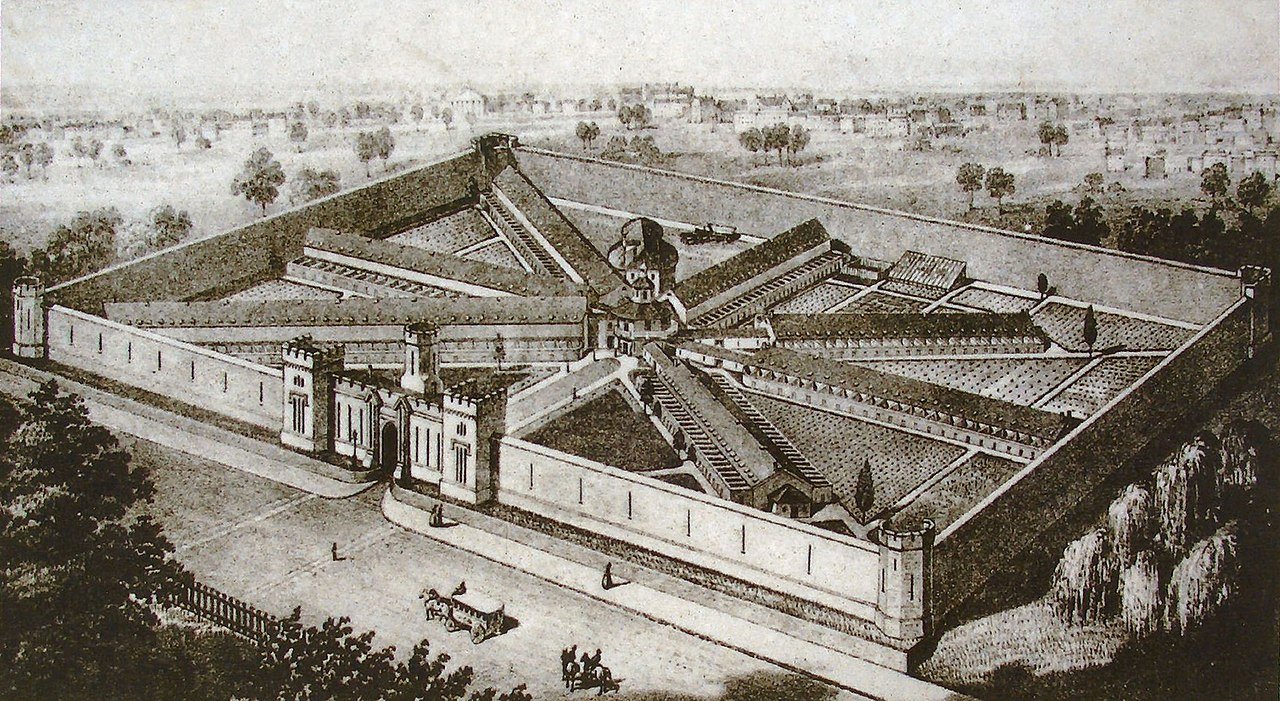

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, a wave of Enlightenment reformers—Quakers in America, evangelicals in England, and progressives in Prussia—looked at the public floggings, stocks, and executions of the time with horror.

They considered physical violence barbaric. They proposed a ‘kinder’ alternative based on monastic life. If you locked a man in total silence, gave him a Bible, and isolated him from the “moral contagion” of other criminals, he would surely reflect, repent, and emerge a new man.

The historical irony is bitter: these 19th-century reformers inadvertently created the infrastructure of mass detention. They proved that the State could take thousands of citizens, strip them of their names, clothe them in uniforms, stack them in barracks (or cells), and completely regulate their calories, movement, and time.

The question of whether imprisonment should cure or punish would never be definitively settled—and both totalitarian systems of the twentieth century would claim, with varying degrees of sincerity, that their camps were instruments of reformation.

–

The Evolution Of The Soviet GULAG

“We stand for organised terror—this should be frankly admitted… Our aim is to fight against the enemies of the Soviet Government.”

Felix Dzerzhinsky, head of the Soviet Cheka

The Soviet camp system preceded Nazi Germany by more than a decade, and its origins lay partly in the very experiences of imprisonment its founders had suffered—and apparently learned nothing humane from.

Nearly every Bolshevik leader who seized power in 1917 had done time in Tsarist prisons or Siberian exile.

This was not coincidental—it was almost a prerequisite for revolutionary credibility.

Lenin spent over a year in pre-trial detention before being exiled to Shushenskoye, where the supposedly “minor threat” was permitted to swim in the Yenisei River, hunt duck, and complete ‘The Development of Capitalism in Russia’. His future wife, Nadezhda Krupskaya, joined him in exile; they married there in 1898.

For Lenin, and for many other Soviet leaders, prison was a finishing school.

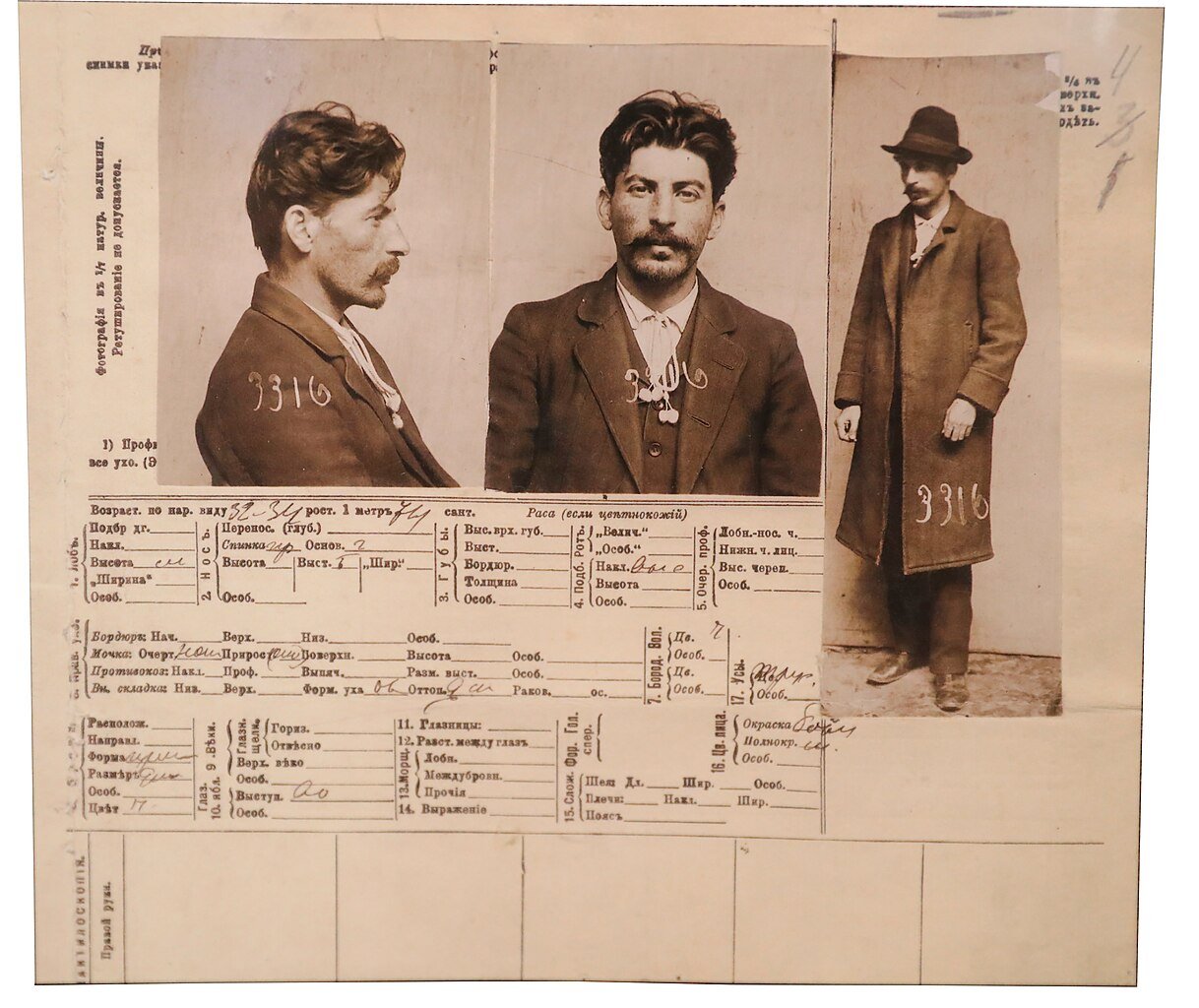

Stalin was arrested seven times between 1902 and 1913, escaping exile five times.

Only his final banishment—four years beyond the Arctic Circle in the Turukhansk district—proved inescapable. He learned to hunt and fish with the local Evenk people, adapted to subzero temperatures, and waited.

“Two years of revolutionary activity among the workers in the oil industry steeled me as a practical fighter,” he later reflected on an earlier imprisonment. “I thus received my second revolutionary baptism of fire.”

Lev Davidovich Bronstein, more popularly known as Leon Trotsky, is widely rumoured to have adopted his famous pseudonym from a jailer in Odessa prison – an ironic choice that became his revolutionary identity.

Imprisoned after organising the South Russian Workers’ Union in 1898, he escaped in 1902 hidden in a hay cart. After the failed 1905 Revolution, he was sentenced to life exile in Siberia but escaped again, traveling 400 miles over seven days through “an icy, roadless desert of white emptiness” on a sleigh drawn by reindeer and driven by an intoxicated Zyryan tribesman.

In his autobiography, Trotsky confessed he “quite liked incarceration” because it gave him time for systematic reading and writing.

If these Tsarist penal facilities were the staging point for the revolution – a time for reading and gaining strength in exile – the GULAG was the lessons in that revolutionary zeal implemented on a wide scale.

The first Soviet forced-labour camps emerged almost immediately after the October Revolution.

On April 15th 1919, a decree inaugurated the system; by the early 1920s, 84 camps operated across the Soviet Union for ‘reforming’ political dissidents.

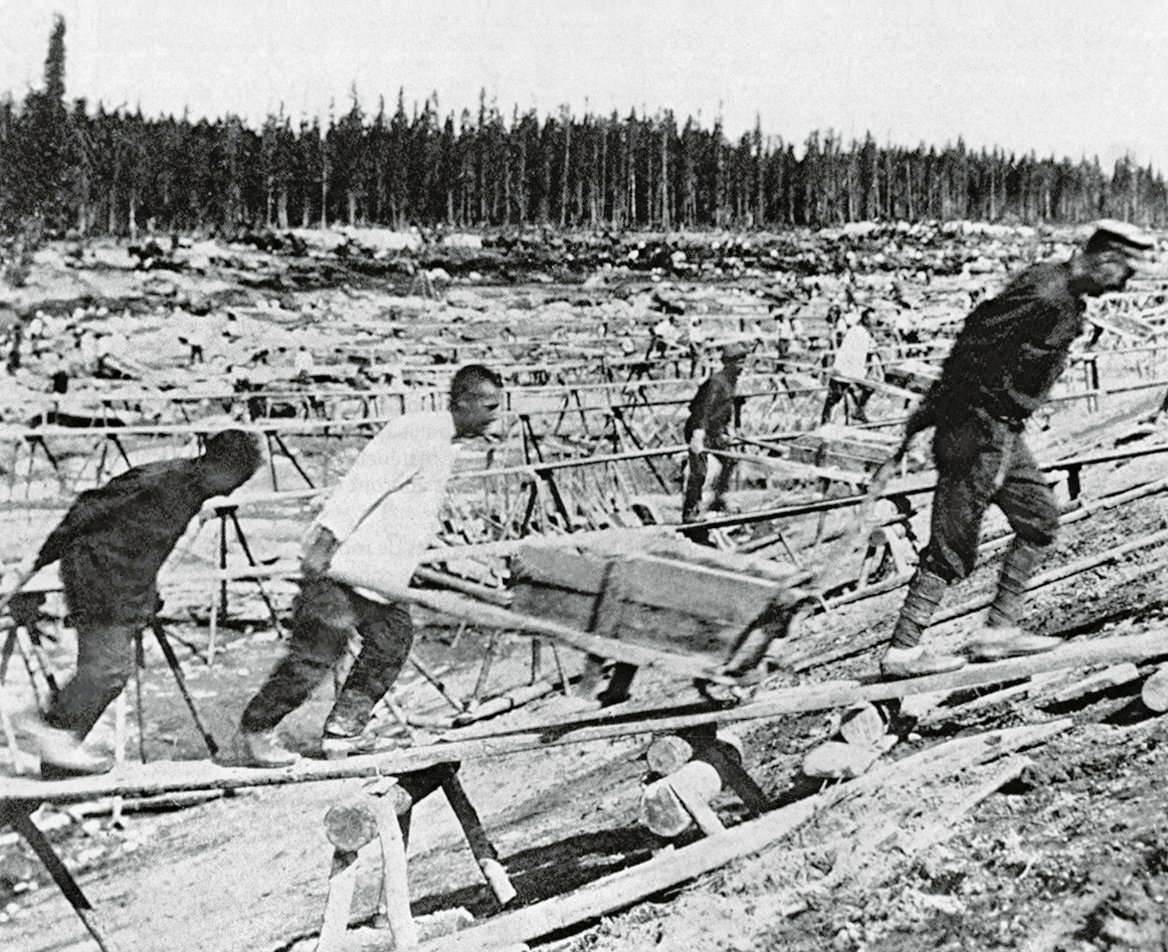

The Solovki prison camp on the Solovetsky Islands became ‘the first camp of the GULAG’, pioneering forced labour as a “method of reeducation.”

The administrative apparatus evolved in layers: the Cheka (1917-1922), then the OGPU (1922-1934), then the NKVD (1934-1946), and finally the MVD.

On April 25th 1930, the GULAG—Glavnoye Upravleniye Lagerei, or Main Directorate of Correctional Labor Camps—was officially established.

Its population growth was staggering: approximately 100,000 prisoners in the late 1920s, 800,000 by 1935, 1.5 million by 1941, and 2.4-2.5 million at its early-1950s peak.

The expansion coincided with Stalin’s ‘revolution from above’ – forced collectivisation and rapid industrialisation. Dekulakisation, the campaign to eliminate so-called wealthy peasants, saw 2.14 million kulaks deported between 1930 and 1933, with at least 20,000 executed. In 1931 alone, over 1.8 million people were exiled.

The camps became essential to the Soviet economy, providing 46.5% of the nation’s nickel, 76% of its tin, 60% of its gold, and 25% of its timber through forced labour.

The Great Terror

The system’s most horrific phase came during 1936-1938, the period Robert Conquest’s landmark study named the ‘Great Terror’.

Three Moscow show trials eliminated the old Bolshevik leadership—Zinoviev, Kamenev, Bukharin, Rykov, and even former NKVD chief Yagoda were among those executed after confessions extracted through torture and threats against families.

“The confessions of guilt of many arrested and charged with enemy activity were gained with the help of cruel and inhuman tortures,” Khrushchev later acknowledged.

But these show trials were merely the visible tip.

NKVD Order No. 00447, issued July 30th 1937, directed mass operations against ‘ex-kulaks’ and ‘anti-Soviet elements’, with regional quotas for arrests and executions decided by three-person tribunals called troikas. In just two days – July 10th-11th 1937 – the Politburo approved death sentences for approximately 23,000 people and exile for 51,000 more.

Soviet archives document 681,692 executions during 1937-1938 alone.

The Geography Of Suffering

The camp complexes bore names that became synonyms for suffering.

Kolyma, in northeast Siberia, was what Solzhenitsyn called “the pole of cold and cruelty” – temperatures dropping to minus sixty degrees Celsius, mortality estimated at 75-80% within the first year.

Between 250,000 and over one million perished there from 1930 through the mid-1950s.

Vorkuta, 100 miles above the Arctic Circle, held 73,000 prisoners at its 1951 peak, with 132 sub-camps spread across 35,000 square miles.

The camp entrance bore a sign reading “Work in the USSR Is a Matter of Honor and Glory.”

Approximately 200,000 of the two million who passed through died from disease, overwork, and Arctic exposure.

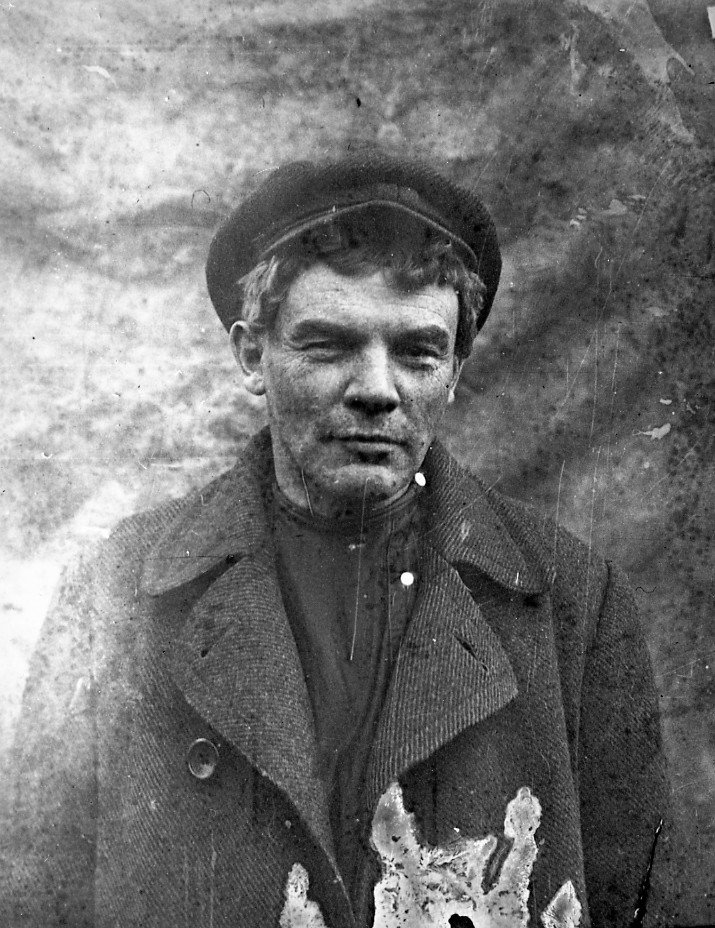

The brutality was both systematic and bureaucratic.

An imprisoned smuggler named Naftaly Frenkel proposed the infamous “you-eat-as-you-work” system (shkala pitaniya), linking food rations to production quotas.

This created a death spiral: inadequate food led to weakness, which led to reduced production, which led to reduced rations, which led to death.

Antoni Ekart, a survivor, recalled a camp doctor examining him: “Too early. If people like you are admitted to hospital, then nobody will be left to do the work.”

Counting The Dead

Scholarly consensus, based on archives opened after 1991, estimates that 18 million people passed through the Gulag system between 1930 and 1953—14 million through camps, 4 million through colonies.

The death toll is more contested.

Archival data suggests 1.5-1.8 million deaths in camps and colonies, though some scholars argue this drastically undercounts “veiled mortality”—prisoners deliberately released when near death to avoid inflating camp statistics.

“Both archives and memoirs indicate that it was common practice in many camps to release prisoners who were on the point of dying,” Anne Applebaum notes.

Critically, as Applebaum and Oleg Khlevniuk confirm, archival researchers have found “no plan of destruction” of the Gulag population and no statement of official intent to systematically kill prisoners.

Releases vastly exceeded deaths; between 1934 and 1953, 20-40% of the population was released annually.

As Timothy Snyder observes, “with the exception of war years, a very large majority of people who entered the Gulag left alive.”

This would not be true of the system developing simultaneously in Germany.

–

The Crooked Road - From Dachau To Auschwitz

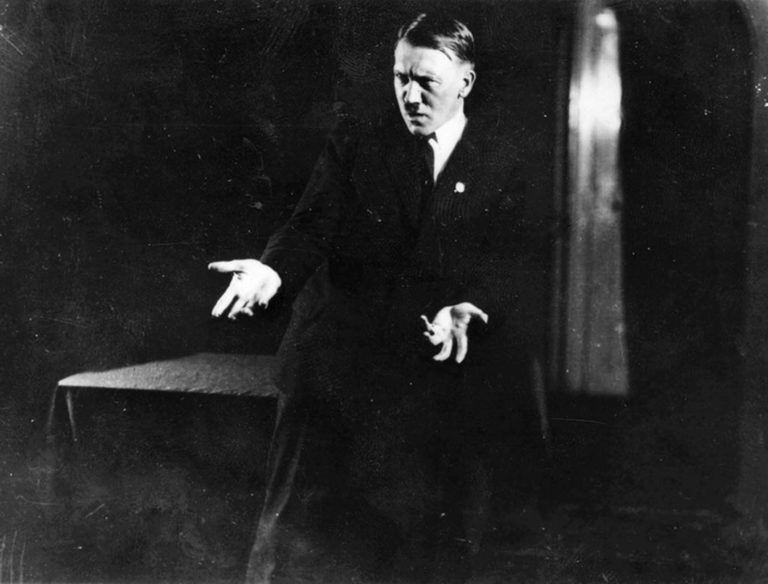

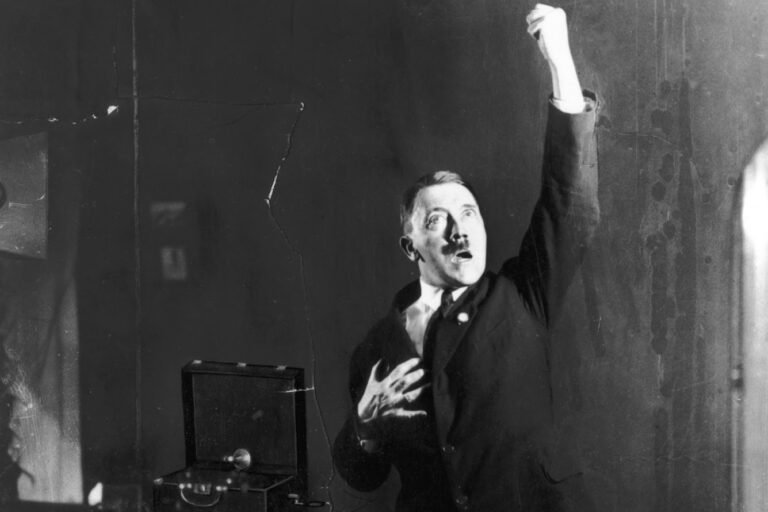

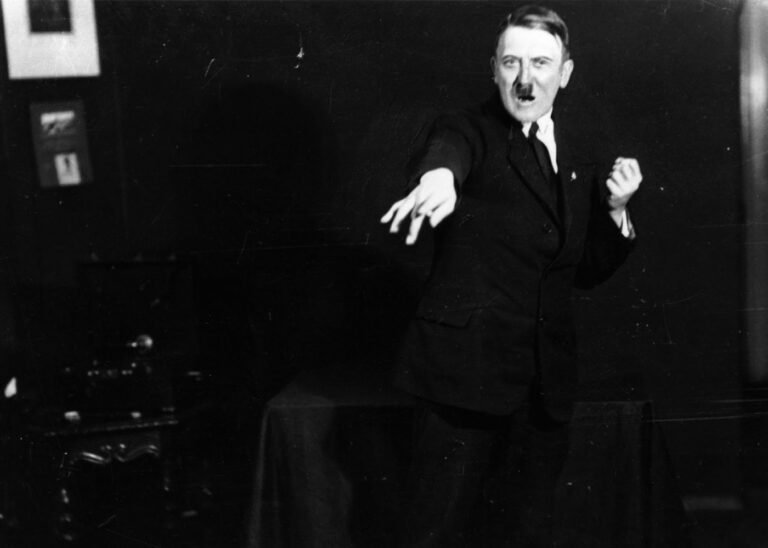

“There was no precedent for what the SS created… It was a ‘university of violence’ where young men were trained to lose their conscience.”

Nikolaus Wachsmann, historian and author of ‘KL: A History of the Nazi Concentration Camps’

When the Nazis seized power on January 30th 1933, they inherited no GULAG – but they improvised quickly.

Within weeks, ‘wild’ detention facilities sprang up across Germany: schools, pubs, abandoned factories commandeered by local Sturmabteilung units to hold Communists, Social Democrats, and anyone deemed politically unreliable.

Over 100,000 individuals were detained by March 1933.

Conditions varied wildly; at least 600 documented deaths occurred in these early concentration camps during the first half of the year.

The first step toward systematisation came on March 22nd 1933, when Heinrich Himmler personally announced the opening of Dachau in the Münchner Neueste Nachrichten. Located just eleven miles from Munich—the “Capital of the Movement”—it was described as “the first concentration camp for political prisoners” with a capacity for 5,000.

Dachau was meant to be visible.

As historian Nikolaus Wachsmann demonstrates, the Nazis initially spoke of concentration camps “with pride and openness,” justifying them as necessary for the ‘protection’ of German society from internal threats.

The Legal Architecture Of Lawlessness

The crucial legal instrument for the development of these detention facilities was the Reichstag Fire Decree.

On February 27th 1933 – six days before parliamentary elections—the Reichstag building was gutted by fire.

The Nazis blamed Communists; a Dutch anarchist named Marinus van der Lubbe was arrested at the scene. The next day, President Hindenburg issued the ‘Decree for the Protection of People and State’, suspending fundamental rights: personal freedom, inviolability of the home, privacy of communications, freedom of expression and assembly, and guarantee of property.

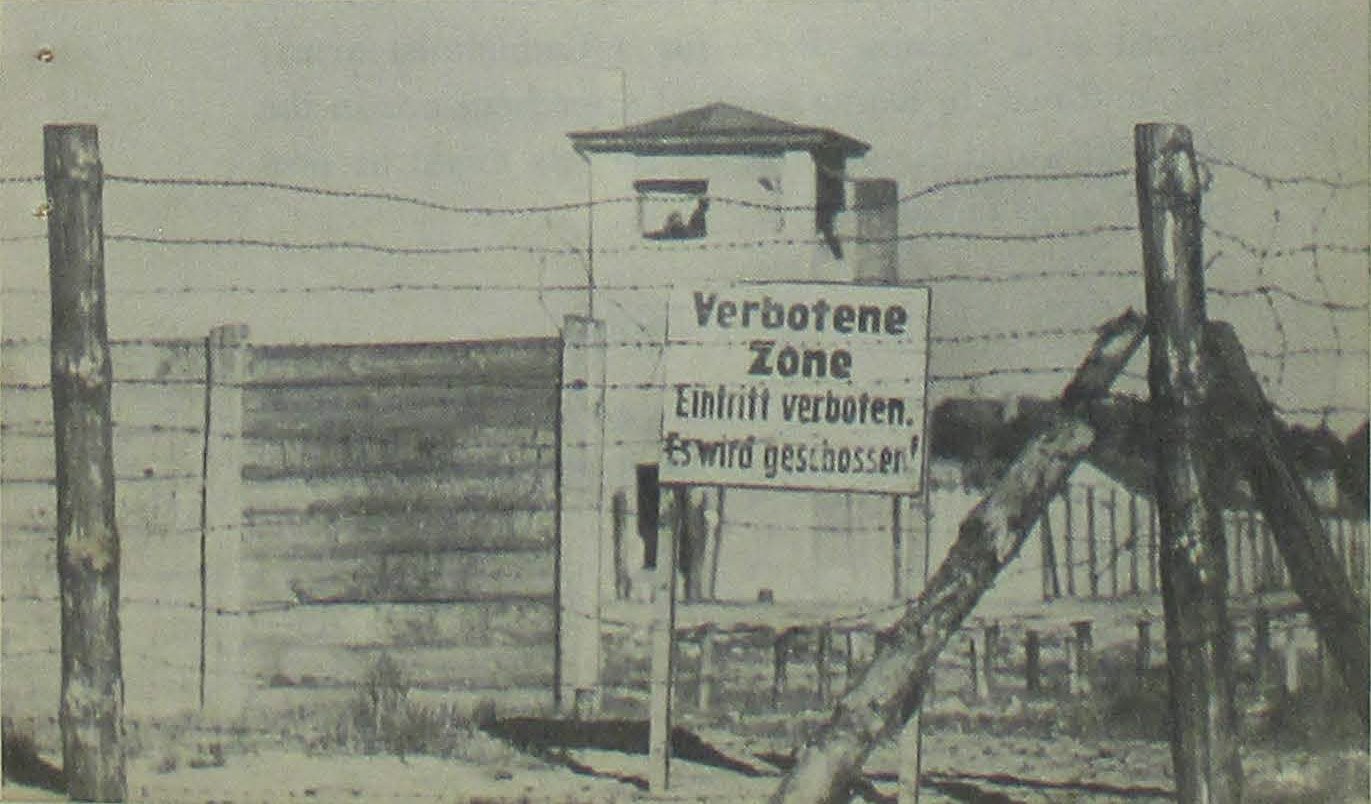

This emergency decree remained in force until Germany’s surrender in 1945—a permanent state of emergency enabling indefinite detention through Schutzhaft (protective custody). The term was deliberately Orwellian: prisoners were held in ‘protective custody camps’ ostensibly to protect society from them.

Within hours of the decree, thousands were arrested.

By mid-March, approximately 10,000 Communists had been detained.

Two weeks after the fire, the Enabling Act granted Hitler’s cabinet power to decree laws without Reichstag approval. With Communist deputies arrested or in hiding and SA men intimidating representatives in the chamber, it passed with 85% support.

German democracy had effectively legislated itself out of existence.

Theodor Eicke And The Template Of Terror

The transformation of wild camps into a systematic terror apparatus came through one man: Theodor Eicke.

Taking command of Dachau on June 26th 1933, this “fanatically dedicated Nazi and a gifted organiser, as well as a stubborn, ruthless, and brutal man” (as Harold Marcuse describes him) codified camp procedures that would become standard across the system.

Eicke’s October 1933 regulations prescribed graduated punishments from loss of mail privileges through corporal punishment to execution – mandatory for “political agitation, spreading of propaganda, any acts of sabotage or mutiny, attempted escape or aid in an escape, attacking a sentry.”

Crucially, he rotated responsibility for administering punishments among guards, ensuring collective participation in brutality. He introduced the striped prisoner uniform and the Death’s Head skull insignia for guards, instilling in his men the belief that “the SS were the only soldiers in peacetime facing the enemy day and night: the enemy behind the barbed wire.”

On July 4th 1934 – days after personally executing Sturmabteiling (SA) leader, Ernst Röhm, during the Night of the Long Knives – Theodor Eicke was appointed as Inspector of Concentration Camps by Heinrich Himmler.

Dachau’s system thus became the template for all subsequent camps:

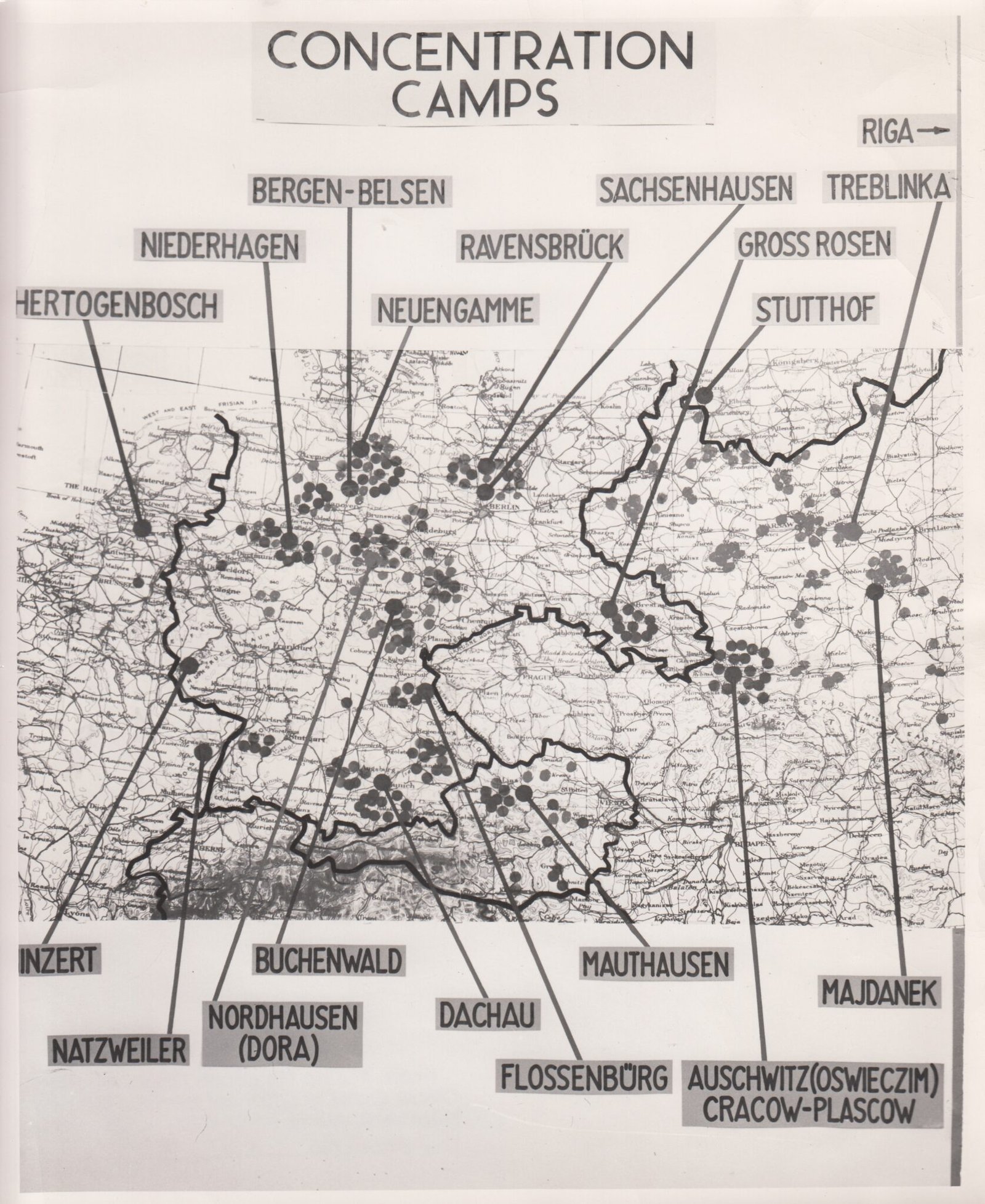

Sachsenhausen (1936), Buchenwald (1937), Flossenbürg (1938), Mauthausen (1938), Ravensbrück (1939).

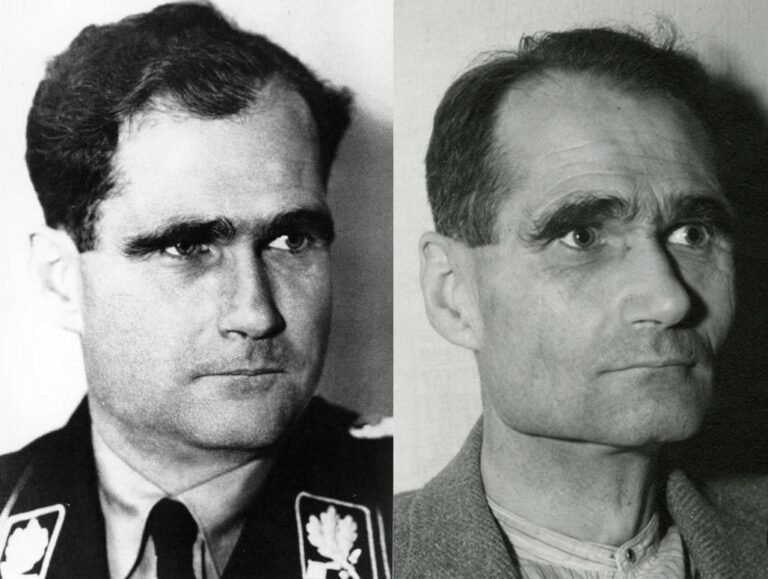

Rudolf Höss, future commandant of Auschwitz, trained under Eicke at Dachau.

The Distinction That Matters

Between 1933 and 1945, the Nazis established over 44,000 camps and incarceration sites.

But a crucial distinction here must be made between concentration camps—which served detention, forced labour, and terror—and the six extermination camps, all located in occupied Poland:

Majdanek, opened in 1941 for the ‘special treatment’ (a Nazi euphemism) of the Jews from the Lublin ghetto – Chełmno (December 1941) pioneered mass murder using gas vans.

Bełżec (March 1942), Sobibór (May 1942), and Treblinka (July 1942) were purpose-built killing facilities staffed by only 20-35 SS men each, augmented by Trawniki auxiliaries and Jewish Sonderkommando prisoners. At Treblinka alone, an estimated 870,000-925,000 perished—nearly all within hours of arrival.

Auschwitz-Birkenau was unique as both a concentration and extermination camp. Its four gas chamber-crematoria complexes, designed by the J.A. Topf & Söhne company, could gas and cremate up to 12,000 people daily.

When capacity was exceeded, bodies were burned in open-air pits. Approximately 1.1 million people were murdered there—960,000 of them Jews.

As Timothy Snyder calculates in Bloodlands, the Germans deliberately killed approximately 11 million noncombatants during the Nazi era, rising to more than 12 million including foreseeable deaths from deportation, hunger, and camp sentences.

–

The Strange Afterlives Of The Nazi Camps

“The liberated prisoner was transferred from one barbed wire enclosure to another. The liberation was a lie.”

Wolfgang Leonhard, historian and contemporary witness

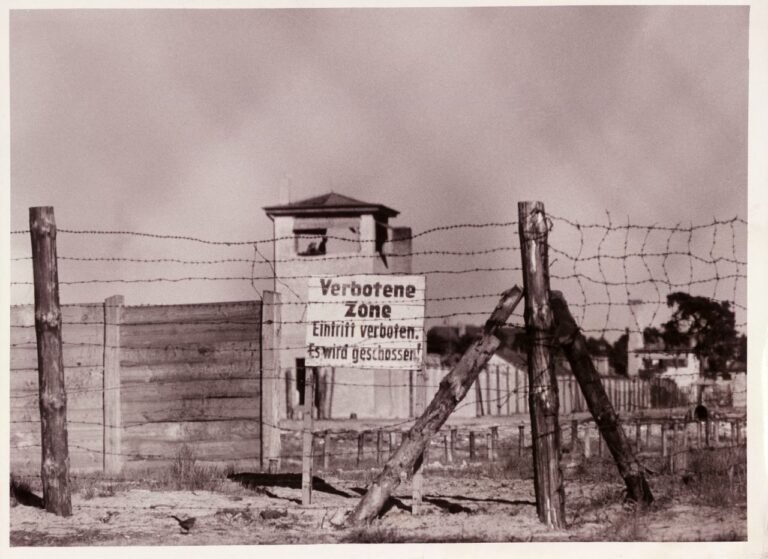

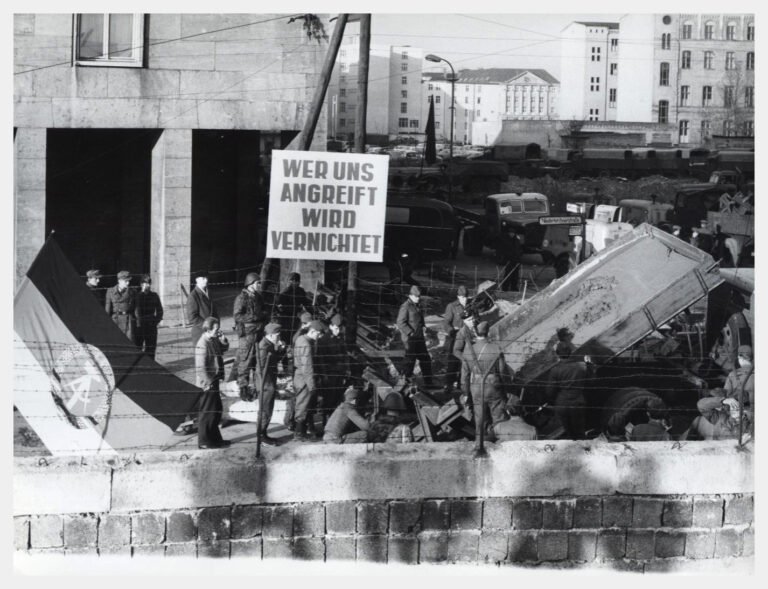

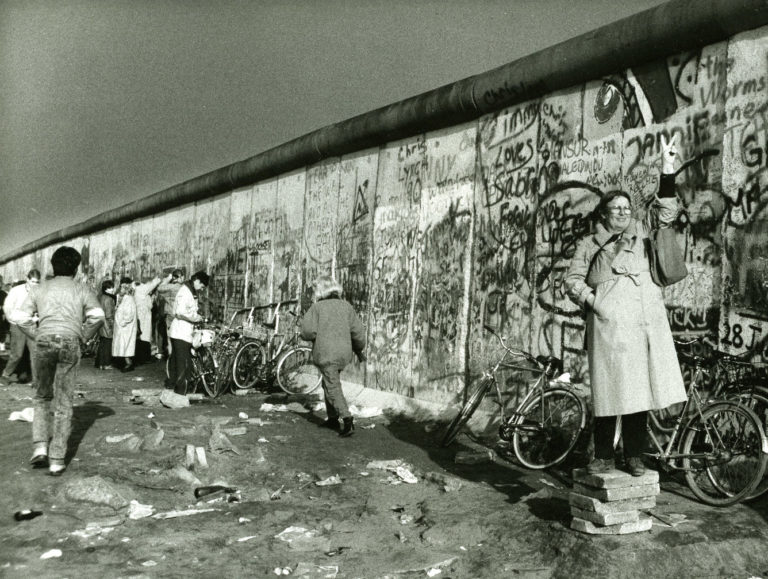

When Soviet forces liberated the Nazi concentration camp of Sachsenhausen, just north of Berlin, in April 1945, one might have expected the site’s horrors to end.

Instead, within months, the NKVD converted it into Special Camp No. 7 (later No. 1).

The Soviet special camp system, established under Beria Order No. 00315, nominally served denazification.

Ten camps held approximately 123,000 Germans; 43,000 died—a mortality rate around 35%. Sachsenhausen was the largest, with 60,000 total internees and 12,000 deaths, primarily from malnutrition and disease during the ‘Winter of Hunger’ of 1946-47.

The prisoner categories revealed much about Soviet priorities.

- Roughly 30,000 were Nazi functionaries held without trial under the Potsdam Agreement.

- But 16,000 more were Soviet Military Tribunal convicts—sentenced after brutal interrogations and tortured confessions for offenses often unrelated to Nazism.

- Another 6,500 were Wehrmacht officers transferred from Western Allied POW camps.

- Over 7,000 were Soviet citizens—former forced laborers, Red Army soldiers, émigré anti-Communists

Unlike the Nazi camp, the Soviet Sachsenhausen was not a labour camp—prisoners were often forbidden to work, leading to psychological and physiological deterioration. It was a Schweigelager, a silence camp, with total isolation from the outside world. Families often learned nothing of their relatives’ fates for years.

Deaths came from starvation, tuberculosis, and dysentery—not from gas chambers or systematic execution.

At closure in 1950, 5,151 convicts were released; 4,836 were transferred to East German authorities; 721 were sent to Waldheim prison for show trials, some receiving death sentences. Mass graves discovered after reunification contained remains of prisoners whose families had never been notified.

–

Reckoning And Remembrance

“A man who stays in the camps for a long time will learn nothing good. He will learn to lie, to hate, to cheat… But he will also learn that the only thing that matters is surviving until the morning.”

Varlam Shalamov, GULAG survivor and author of ‘Kolyma Tales’

Germany’s confrontation with its Nazi past – Vergangenheitsbewältigung – has no parallel in post-Soviet Russia.

Since the 1952 Luxembourg Agreement, Germany has disbursed over $70 billion in compensation to Holocaust victims; approximately 1.6 million forced laborers received one-time payments through the Foundation “Remembrance, Responsibility and Future.” Criminal prosecutions continue; mandatory education and extensive memorialisation shape national identity.

The Holocaust Memorial in Berlin – 2,711 concrete stelae – stands minutes from the Reichstag and the central government quarter, part of collection of memorial for the Victims of National Socialism in the same area.

At the Sachsenhausen Memorial, a museum covering the Soviet camp era opened in 2001; the site’s Book of the Dead, documenting 11,889 Soviet-era deaths, was published in 2010.

Russia, on the other hand, offers a painful contrast.

A brief de-Stalinisation under Khrushchev and Glasnost-era opening gave way to Putin-era rehabilitation of Stalin’s image and the 2022 closure of Memorial, the organisation that had documented Soviet repression since 1989.

The Wall of Grief, erected in 2017, remains the only major Moscow memorial to terror victims.

Archives have become increasingly restricted.

No compensation exists for GULAG survivors or their descendants.

–

Conclusion

“Monsters exist, but they are too few in number to be truly dangerous. More dangerous are the common men, the functionaries ready to believe and to act without asking questions.”

Primo Levi, survivor of Auschwitz

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn wrote that “the line separating good and evil passes not through states, nor between classes, nor between political parties either—but right through every human heart.”

Both the Nazi and Soviet systems recruited ordinary human beings to administer extraordinary cruelty.

Both wrapped their atrocities in ideological justification—racial purity in one case, class struggle in the other.

Both demonstrated how bureaucratic rationality could serve irrational ends.

Yet the differences matter.

The Soviet system, for all its horrors, was not designed for genocide. Jews who entered the Gulag had reasonable prospects of survival—they faced the same brutal conditions as other prisoners, not selection for immediate death. Roma, homosexuals, and the disabled were not systematically murdered. The GULAG was a catastrophe of exploitation and indifference; the Nazi camps were something categorically different—the deliberate, industrialised annihilation of entire peoples.

The Final Accounting

Total prisoners: The GULAG held approximately 18 million people (1930-1953); Nazi camps and killing sites held far fewer at any given time but murdered at far higher rates.

Deaths: Scholarly consensus places GULAG deaths at 1.5-1.8 million (some argue 6 million when accounting for veiled mortality). Nazi Germany deliberately killed 11-12 million noncombatants, including 6 million Jews.

Mortality rates: In the GULAG, 20-40% were released annually; most who entered left alive. While the Nazi concentration camps were more lenient in their early years, allowing some to be released, this was put to an end with the start of the Second World War – and in Nazi extermination camps, survival was measured in weeks.

Method of death: GULAG victims died primarily from starvation, disease, exhaustion, and exposure – byproducts of exploitation rather than goals. Nazi concentration camp victims were shot en-masse, hanged, gassed, and intentionally worked to death..

Possibility of release: GULAG sentences were definite (though often arbitrarily extended); release was common. Concentration camp inmates were indefinitely detained – and Nazi death camp victims had no prospect of release—their murder was the camps’ purpose.

Possibility of escape: Both systems were heavily guarded, but Nazi camps were specifically designed to structure their terror (in the case of Sachsenhausen, in particular), prevent escape and destroy evidence of murder; the few successful escapes (like from Sobibór and Treblinka) required organised revolts.

The fundamental distinction though is between a system that killed through neglect and exploitation versus one that killed through industrialised genocide.

Whether that be the mass killings in the Nazi Vernichtungslager or the ‘annihilation through work’ that Heinrich Himmler would describe as the function of the concentration camps.

The GULAG was, as Solzhenitsyn called it, a system of “destructive-labour camps”—destructive, but labour-oriented.

The Nazi camps were designed, with increased effectiveness over time, as factories of death.

***

If you’ve enjoyed reading this article, consider booking one of our private guided tours of Berlin.

Bibliography

Applebaum, Anne (2003), Gulag: A History, Doubleday, ISBN 0767900561

Applebaum, Anne (2012), Iron Curtain: The Crushing of Eastern Europe, 1944–1956, Doubleday, ISBN 978-0385530804

Bentham, Jeremy (1791), Panopticon, or The Inspection House, T. Payne, ISBN 978-1120016140

Conquest, Robert (1990), The Great Terror: A Reassessment, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195055801

Figes, Orlando (2007), The Whisperers: Private Life in Stalin’s Russia, Allen Lane, ISBN 978-0713996168

Foucault, Michel (1975), Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, Gallimard / Pantheon Books, ISBN 978-0394499420

Funder, Anna (2003), Stasiland: Stories from Behind the Berlin Wall, Granta Books, ISBN 978-1862076207

Hilberg, Raul (2003), The Destruction of the European Jews (3rd ed.), Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0300095920

Hobhouse, Emily (1902), The Brunt of the War and Where It Fell, (No standard ISBN; varies by modern reprint)

Howard, John (1777), The State of the Prisons in England and Wales, William Eyres / T. Cadell & N. Conant, ISBN 978-1379443490

Kershaw, Ian (1998), Hitler 1889–1936: Hubris, W. W. Norton & Company, ISBN 978-0393327476

Khlevniuk, Oleg V. (2004), The History of the Gulag: From Collectivization to the Great Terror, Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0300104073

Koehler, John (1999), Stasi: The Untold Story of the East German Secret Police, Bantam, ISBN 978-1857026915

Levi, Primo (1947), If This Is a Man / Survival in Auschwitz, Abacus, ISBN 978-1841956041

Levi, Primo (1986), The Drowned and the Saved, Abacus, ISBN 978-1841956058

Marcuse, Harold (2001), Legacies of Dachau, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0521800225

Montefiore, Simon Sebag (2007), Young Stalin, Vintage, ISBN 978-0099520859

Naimark, Norman (1995), The Russians in Germany: A History of the Soviet Zone of Occupation, 1945–1949, Belknap Press, ISBN 978-0674317495

Range, Peter Ross (2016), 1924: The Year That Made Hitler, Pegasus Books, ISBN 978-1681774157

Semple, Janet (1993), Bentham’s Prison: A Study of the Panopticon Penitentiary, Clarendon Press, ISBN 978-0198273875

Service, Robert (2000), Lenin: A Biography, Macmillan, ISBN 978-0333669909

Service, Robert (2004), Stalin: A Biography, Macmillan, ISBN 978-0333748928

Service, Robert (2009), Trotsky: A Biography, Macmillan, ISBN 978-0330522382

Shalamov, Varlam (various years), Kolyma Tales, Penguin Books, ISBN 978-0141187980

Snyder, Timothy (2010), Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin, Basic Books, ISBN 978-0465031474

Solzhenitsyn, Aleksandr (1973), The Gulag Archipelago, YMCA Press (original), English translation (1974) Harper & Row, ISBN 0-06-013914-5

Van Heyningen, Elizabeth (2013), The Concentration Camps of the Anglo-Boer War: A Social History, Jacana Media, ISBN 978-1431405442

Wachsmann, Nikolaus (2015), KL: A History of the Nazi Concentration Camps, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, ISBN 978-0374299722

HISTORICAL ARTICLES

Mythbusting Berlin

Are There Any Nazi Statues Left In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

Visitors to Berlin often arrive expecting to find the physical remnants of the tyranny of the 20th century still standing – statues of dictators, triumphal arches, or bronze idols. Instead, they often find none. The stone symbols and statues of the Third Reich are still gazing down on them, however, hiding in plain sight. But why are there no statues of Hitler? Did the Allies destroy them all in 1945, or is the truth stranger

Could The Western Allies Have Captured Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

To contemplate a Western Allied capture of Berlin in 1945 is to challenge the established endgame of the Second World War. What was the true military and logistical feasibility of a Western Allied assault on the Nazi capital? What factors truly sealed Berlin’s fate, and what might have changed had the Allies pushed eastward?

Answering these questions means delving into the complex interplay of logistics, political maneuvering, and the competing visions for a post-war world

Did Any Of The Rothschild Dynasty Die In The Holocaust? – Mythbusting Berlin

The Rothschild name is synonymous with immense wealth, influence, and persistent conspiracy theories—especially during the era of Nazi Germany. Often targeted by antisemitic propaganda, the family’s survival during World War II has sparked myths about their supposed immunity from Nazi persecution. But did any Rothschild family member actually perish in the Holocaust? This article explores that compelling question, unraveling historical misconceptions and revealing the reality behind one of Europe’s most famous dynasties.

Did Frederick The Great Introduce The Potato To Germany? – Mythbusting Berlin

One of the more bizarre claims to fame attributed to the first King of Prussia is that the man who would go down in history known as Frederick the Great introduced the potato to Germany during his reign back in the 1700s. This starchy root vegetable has undoubtedly become a staple part of German cuisine – an essential addition to any plate of Schnitzel, Schweinshaxn, and Königsberger Klopse – however, whether Frederick the Great is

Did Hitler Escape To Argentina In 1945? – Mythbusting Berlin

Although Nazi leader, Adolf Hitler, certainly remains an inescapable figure, could there be any truth to the story of his escape to Argentina in 1945? That the most wanted man on earth could simply vanish, to spend the rest of his life peacefully in South American obscurity captivates imaginations. Yet, despite numerous investigations, this tale persists primarily as myth—fueled by speculation, hearsay, and conspiracy theories.

Did Hugo Boss Design The Nazi Uniforms? – Mythbusting Berlin

The idea that Hugo Boss – the man whose name now adorns expensive suits and fragrances – was the creative genius behind the Nazi uniforms suggests a terrifying collision of haute couture and holocaust – a marriage of high style and high crimes. The image is striking: a German tailor sketching the ultimate villain’s costume. But history, as usual, is far messier, more bureaucratic, and more banal than the internet memes suggest. To understand who

Did Rudolf Hess Really Commit Suicide? – Mythbusting Berlin

On a summer’s day in 1987, the last Nazi war criminal of the Nuremberg trials was found dead in a prison built for hundreds, yet for two decades, housed only him. The official verdict was suicide, a straightforward end to a life defined by fanaticism, delusion, and contradiction.

But the simplicity of the report belied the complexity of the man and the 46 years he had spent in Allied custody. In the meticulously controlled

Did The Nazis Develop Nuclear Weapons? – Mythbusting Berlin

The Nazi obsession with super-weapons became so serious in the closing stages of the Second World that Adolf Hitler personally believed that such ‘Wunderwaffen’ both existed in a usable form – and would save the country from defeat. Had the Nazis managed to develop nuclear weapons by 1945 – the outcome of the war would surely have been different. But how close were Hitler, Himmler, and his henchmen to developing an A-bomb?

Did The Nazis Invent Decaf Coffee? – Mythbusting Berlin

Persistent rumors claim that Nazis preferred their coffee anything but pure, leading some to wonder if they might have influenced the development of decaffeinated coffee. Although decaf was already widely available across Europe by the mid-20th century, speculation continues: could the Nazis really have played a role in popularizing—or even discovering—this caffeine-free alternative, or is this simply another caffeinated conspiracy cooked up to sensationalize an ordinary historical detail?

Did The Nazis Invent The Bicycle Reflector? – Mythbusting Berlin

The fruits of wartime ingenuity are plenty – so many, in-fact, that it has become somewhat of a worn cliche that as the guns start firing the innovators get to work, often solving problems while providing more problems for the enemy to overcome.The kind of progress that results in the production of newer improved, more lethal weapons, such as to increase the chances of victory.

Did The Nazis Run The Largest Counterfeiting Operation In History? – Mythbusting Berlin

During the Second World War the Nazis masterminded an astonishing plot to destabilise Britain by flooding its economy with counterfeit banknotes. Crafted in secret by concentration camp prisoners, this forged fortune became the most ambitious counterfeiting operation ever attempted. But was it history’s largest? Dive into the extraordinary tale of Operation Bernhard,

rife with deception, survival, and intrigue—revealing the truth behind one of the Third Reich’s most audacious schemes and its surprising legacy.

Did The Second World War End In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

When is a war ever truly over? When the last shot is fired in anger would seem like the best measure. Rarely, though, is it possible to gain insight into such a moment.

Remarkably, a record still exists of such a moment at the end of the First World War on the Western Front. A seismic register and recording of the last belching battery of British guns firing artillery across no-man’s-land, followed by a profound

Did The Spanish Flu Pandemic Help The Nazis Take Power? – Mythbusting Berlin

The devastating Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918-1919 struck amid Germany’s post-war turmoil, compounding social instability, economic hardship, and widespread political disillusionment. Could this catastrophic health crisis have indirectly paved the way for Nazi ascension? While often overshadowed by war and revolution, the pandemic’s profound psychological and societal impacts arguably contributed to the perfect storm, enabling extremist ideologies—including Nazism—to gain popularity and ultimately seize power in a fractured Germany.

Have Adolf Hitler’s Remains Been DNA Tested? – Mythbusting Berlin

In the smouldering ruins of Berlin in 1945, the world’s most wanted man vanished. Did Adolf Hitler, as official history attests, die by his own hand in the Führerbunker? Or did he escape, fuelling a thousand conspiracy theories that have echoed for decades? For years, the Soviets claimed to hold the gruesome proof of his death: a skull fragment and a set of teeth, locked away in Moscow archives. But in an age of definitive

How Did The Nazi Concentration Camps Differ From The Soviet GULAG?

The Nazi concentration camps and Soviet Gulag system have often been conflated in popular imagination—twin symbols of twentieth-century totalitarian horror. Yet the two systems operated on fundamentally different principles. One extracted labor to fuel industrialisation while accepting mass death as collateral damage; the other evolved into purpose-built machinery of genocide. Understanding these distinctions isn’t merely academic—it reveals how different ideologies produce different atrocities, and why Germany and Russia reckon with these legacies so differently today.

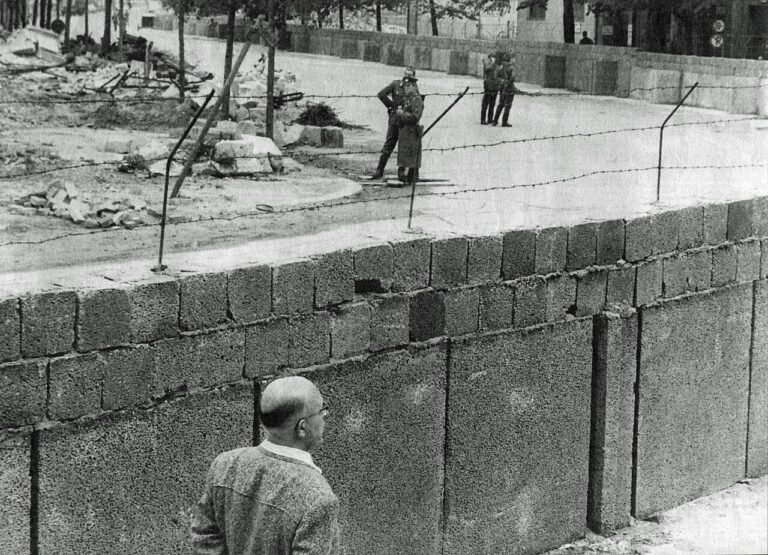

How Long Did It Take To Build The Berlin Wall? – Mythbusting Berlin

It is one of the most enduring images of the 20th century: a city divided overnight. The popular narrative tells us that Berliners went to sleep in a unified city and woke up in a prison. While the shock of August 13th 1961, was very real, the idea that the ‘Wall’ appeared instantly is a historical illusion. The physical scar that bisected Berlin was not a static creation, but a living, malevolent beast that evolved

How Many Assassination Attempts On Adolf Hitler Were There? – Mythbusting Berlin

Nazi leader, Adolf Hitler, projected an aura of invincibility, a man of destiny shielded by providence. But behind the carefully constructed image of the untouchable Führer lies a story of constant threat, of bombs that failed to detonate, and errant bullets that missed their mark. Unearth the hidden history of the numerous attempts on Hitler’s life as we explore the courage of those who tried to change the course of history and the devil’s luck

How Many Jews Died In The Holocaust? – Mythbusting Berlin

The answer to the question posed of how many Jews died in the Holocaust is a simple one: too many. That merely one death was an unforgivable obscenity is a fundamental and necessary realisation in understanding the capriciousness of this unparalleled racial genocide. To comprehend, however, the full number of Jews murdered in Europe by the Nazi regime in the 1930s and 1940s is a detective story of epic proportions: the evidence overwhelming, multifaceted, and

How Many People Died Trying To Escape East Germany? – Mythbusting Berlin

The image of the Berlin Wall is seared into our collective memory, a concrete symbol of Cold War oppression. We think of the daring escapes and the tragic deaths of those who failed. But that well-known number is only a fraction of the truth. The story of those who died trying to escape East Germany is far broader and more complex than most imagine, stretching along a thousand-kilometer border and out into the cold waters

How Old Is Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

A relatively new arrival in Europe, Berlin is over 1000 years younger than London, nevermind Rome or Athens, Jerusalem or Jericho. Just how old is Berlin though?

A question fraught with false assumptions and distortions – that has more often than not been answered with propaganda as it has with the cold hard truth.

Was Adolf Hitler A Drug Addict? – Mythbusting Berlin

Solving the enigma of the ‘Führer’ has become a preoccupation for many, since the arrival of the Austrian-German onto the world stage – although moving beyond the mythology without falling into the trap of prejudically extrapolating on the psychopathography of Hitler or demonising so as to excuse his actions has proven problematic. What to make of the man who became more than the sum of his masks? The painter; the military dilettante, the mass murderer,

Was Adolf Hitler A Freemason? – Mythbusting Berlin

History abhors a vacuum, but adores a mystery. Such is the speculative fiction suggesting a secret allegiance behind the rise of the Third Reich – that the catastrophe of the Second World War was orchestrated from the shadows of a Masonic lodge. The image of Adolf Hitler—the drifter from Vienna turned dictator—as a covert initiate of the very brotherhood he publicly reviled, however, creates a paradox that collapses under scrutiny. As when we unlock the

Was Adolf Hitler Gay? – Mythbusting Berlin

In the shadowy corridors of Third Reich history, few questions provoke as much tabloid curiosity and scholarly exasperation as the sexuality of Adolf Hitler. For decades, rumors have swirled—whispered by political enemies in 1930s Munich, psychoanalyzed by American spies in the 1940s, and sensationalized by revisionist authors today. Was the dictator who condemned thousands of men to concentration camps for “deviant” behavior hiding a secret of his own? By peeling back the layers of propaganda,

Was Adolf Hitler Jewish? – Mythbusting Berlin

Was the dictator who orchestrated the murder of millions of European Jews secretly one of them? It is perhaps the darkest irony imaginable, a story whispered for decades in backrooms, bars, and conspiracy forums alike. The most-common rumour – the ‘Frankenberger Myth’ – suggests that Adolf Hitler’s paternal grandfather was Jewish, a secret so damaging it could have unraveled the entire Nazi regime. But where does this claim come from? And, more importantly, is there

Was Currywurst Invented In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

Explore the story behind what many consider Berlin’s most iconic snack—the ever-so-humble Currywurst. Often hailed as an enduring symbol of culinary creativity amid Cold War scarcity, this humble dish has inspired fierce debate about its true origin. But was it genuinely invented here in Berlin, or have proud locals simply adopted and elevated this spicy street-food favorite into legendary status all their own?

Was Fanta Invented By The Nazis? – Mythbusting Berlin

As one of the most secretive organisations in the world, the Coca Cola corporation refuses to share its secret recipe with anyone. Famously insisting only on shipping the base syrup of its drinks to plants around the world to be carbonated and distributed.

This combined with the trade limitations of the Second World War may have led to the introduction of one of the most popular soft-drinks in the world. But could it be true:

Was Frederick The Great Gay? – Mythbusting Berlin

Frederick II of Prussia, better known as Frederick the Great, is often remembered as the archetypal enlightened monarch – a brilliant military commander, patron of the arts, and learned philosopher. Yet behind the stern portraits of this 18th-century warrior-king lies a personal life long shrouded in intrigue and speculation. Intrigue around the king’s sexual orientation has persisted through the centuries, chiefly revolving around one question: Was Frederick the Great gay?

Was Henry Ford A Nazi? – Mythbusting Berlin

US auto tycoon, Henry Ford, holds the ignominious distinction of being the only American Adolf Hitler praised by name in his National Socialist manifesto: ‘Mein Kampf’. This was not, as it turns out, the only connection between Ford and the Party of Hitler, Himmler, and the Holocaust.

Ford’s overt affinity with the Third Reich reveals a troubling past. How deep these connections ran, and how consequential they were for both sides, is a chapter

Was The Colour Blue Invented In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

Tracing the true history of blue—from ancient Egyptian dyes to the accidental discovery of Prussian Blue in a Berlin lab. We’ll debunk myths about seeing blue, explore colonial indigo plantations, scale mountains with a cyanometer, and trace Van Gogh’s starry skies—all to answer one question: how did Berlin shape our understanding of the world’s rarest color?

Was The Döner Kebab Invented In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

Unlikely icon of immigrant success; fast food symbol of the working class; over-hyped midnight disco eat; or culturally appropriated cuisine? Its influence goes far beyond layers of seasoned meat and fresh vegetables stuffed into pita bread. But does Berlin deserve credit as the Döner Kebab’s true birthplace, or has the city merely refined and popularized a culinary tradition imported from elsewhere?

Was The Fall Of The Berlin Wall An Accident? – Mythbusting Berlin

On a seasonally crisp night in November 1989, one of the most astonishing events of the 20th century occurred. After twenty eight years, three months, and twenty eight days of defining and dividing the German capital, the Berlin Wall ceased to exist – at least in an abstract sense. Although the removal of this symbol of the failure of the East German system would take some time, its purpose – as a border fortification erected

Was The Nazi Party Democratically Elected? – Mythbusting Berlin

The myth persists that Adolf Hitler rose to power through popular democratic choice. Yet history reveals a darker, more complicated truth. Hitler’s ascent involved exploiting democratic institutions, orchestrating violence, propaganda, and political intrigue—not a simple election victory. Understanding how Germany’s democracy collapsed into dictatorship helps illuminate the dangerous interplay between public desperation, elite miscalculations, and extremist ambition, providing crucial lessons for safeguarding democracy today.

Were The Allied Bombings Of Germany War Crimes? – Mythbusting Berlin

The history of the Allied bombing of Germany during the Second World War still triggers fierce debate. Was reducing cities to rubble a necessary evil – justice from above in a just war – or an unforgivable crime? Can the intentional targeting of civilians ever be justified as militarily necessary?

In a conflict where all rules seemed to vanish, an even more pertinent question persists: by the very standards they would use to judge their

Were The Nazi Medical Experiments Useful? – Mythbusting Berlin

Before the Nazi period, German medicine was considered the envy of the world – a shining monument to progress. But deep within that monument, a rot was spreading, one which would collapse the entire structure into an abattoir. From the wreckage, we are left with a profoundly uncomfortable inheritance: a moral enigma wrapped in doctor’s whites.

What to make of the data, the images, and the terrible knowledge gleaned from unimaginable human suffering. Whether

What Are The Origins Of The Nazi Salute? – Mythbusting Berlin

A specter is haunting the modern mind, a gesture so charged with the dark electricity of history that its mere depiction can unleash a storm of controversy.

It is a simple movement: the right arm, stiff and straight, raised to the sky. But in that simplicity lies a terrifying power, a symbol of a regime that plunged the world into an abyss and a chilling reminder of humanity’s capacity for organised hatred.

This

What Are The Origins Of The Nazi Swastika? – Mythbusting Berlin

Long before the legions of the Third Reich marched beneath its stark, unnerving geometry, the swastika lived a thousand different lives. It was a symbol of breathtaking antiquity, a globetrotting emblem of hope and good fortune that found a home in the most disparate of cultures. To even begin to understand its dark 20th-century incarnation, one must first journey back, not centuries, but millennia.

What Are The Pink Pipes In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

A first-time visitor to Berlin could be forgiven for thinking the city is in the midst of a bizarre art installation. Bright pink pipes, thick as an elephant’s leg, climb out of the ground, snake over pavements, arch across roads, and disappear back into the earth. Are they part of a complex gas network? A postmodern artistic statement? A whimsical navigation system? These theories, all logical, are all wrong. The truth is far more elemental,

What Do The Colours Of The German Flag Symbolise? – Mythbusting Berlin

What does a flag mean? Is it merely a coloured cloth, or does it hold the hopes, struggles, and identity of a nation? The German flag, with its bold stripes of black, red, and gold, is instantly recognisable. But the story of its colours is a tumultuous journey through revolution, suppression, and reinvention. The common explanation for their symbolism is a simple, romantic verse, yet the truth is a far more complex and contested tale,

What Happened To Adolf Hitler’s Alligator? – Mythbusting Berlin

It is often said that you can tell a lot about a person by their relationship with animals; that owners often come to look and behave like their pets. Or is it perhaps more that people choose their pets to correspond to their personality? Nazi leader Adolf Hitler’s love of dogs, for example, is well documented but what is there to make of his relationship with reptiles?

What Happenened To The German Royal Family? – Mythbusting Berlin

When the smoke cleared over the trenches in November 1918, the German Empire had evaporated, and with it, the divine right of the Hohenzollern dynasty. Conventional wisdom suggests the family simply vanished into the sepia-toned obscurity of history books—exiled, forgotten, and irrelevant. But dynasties, like weeds in a landscaped garden, are notoriously difficult to uproot entirely. The story of the German royals did not end with the Kaiser’s flight to Holland; it merely shifted gears.

What Is The Difference Between Fascism & Nazism? – Mythbusting Berlin

While the terms ‘Fascist’ and ‘Nazi’ are often bandied around interchangeably as shorthand for tyranny – Italian fascism and German National Socialism were distinctly different beasts. Albeit ideological kin. One an ideology of state-worship, born from post-war chaos and national pride; the other built upon a fanatical, pseudo-scientific obsession with race. Two peas in the same totalitarian pod – twins in tyranny – more succinctly summarised as the Nazi chicken to the Fascist egg.

What Was Checkpoint Charlie? – Mythbusting Berlin

Checkpoint Charlie remains among Berlin’s most visited historical sites, famed worldwide for its significance during the Cold War. Originally established as a modest border-crossing point, it evolved dramatically over the decades into an international symbol of freedom, espionage, and intrigue. Today, critics and locals often dismiss it as little more than a tourist trap—Berlin’s Disneyland—but how exactly did Checkpoint Charlie get its peculiar name, and what truths hide behind its popularity?

What Was Prussia? – Mythbusting Berlin

Prussia’s legacy is both remarkable and contentious—once a minor duchy, it rose dramatically to shape modern European history. Renowned for military discipline, administrative efficiency, and cultural sophistication, Prussia was instrumental in uniting the German states, laying foundations for a unified Germany. But how did this kingdom, with its roots in Baltic territories, achieve such prominence, and why does its complex history continue to evoke admiration, debate, and occasional discomfort in Germany today?

What Was The Berlin Airlift? – Mythbusting Berlin

In the ruins of 1948, the silence of Berlin was not a sign of peace, but a held breath before a new catastrophe. The city, drowning in rubble and political intrigue, became the staging ground for the twentieth century’s most audacious gamble. While popular history remembers the chocolate parachutes and smiling pilots, the reality of the Berlin Airlift was a terrifying operational nightmare born from a ruthless currency war. It wasn’t just a humanitarian mission;

What Was The Socialist Kiss? – Mythbusting Berlin

It is one of the most curious and enduring images of the Cold War: two middle-aged, grey-suited men, locked in a fervent embrace, their lips pressed together in a kiss of apparent revolutionary passion. This was the ‘Socialist Fraternal Kiss’, a ritual that, for a time, seemed to encapsulate the unwavering solidarity of the Eastern Bloc.

But what was behind this seemingly intimate gesture? Was it a genuine expression of camaraderie, a piece of

Who Built The Berlin Wall? – Mythbusting Berlin

One of the most common questions I have encountered from people curious about Berlin, and often so cryptically phrased. Who built the Berlin Wall? A simple five-word query, yet one that can be read one of two ways. More than thirty years since the ‘Fall of the Wall’, the story of its construction continues to baffle many who are mainly familiar with its existence through knowledge of its importance…

Who Really Raised The Soviet Flag On The Reichstag? – Mythbusting Berlin

One iconic photograph has come to symbolise the Red Army’s victory over Nazi Germany in 1945—the Soviet flag waving triumphantly above Berlin’s battered Reichstag building. Yet behind this enduring image lies controversy, confusion, and political manipulation. Who truly raised the Soviet banner atop the Reichstag? Was it a spontaneous act of heroism or carefully staged Soviet propaganda? Decades later, unraveling the truth reveals surprising layers beneath the mythologized symbol of Soviet triumph.

Who Was Really Responsible For The Reichstag Fire? – Mythbusting Berlin

Various theories have been posited as to who actually set fire to the German parliament in 1933. Was it the opening act in an attempted Communist coup or a calculated false flag operation carried out by elements of the Nazi Party, intended to create the conditions necessary for introducing single-party rule? And what part did the young man from Holland, arrested shirtless inside the building the night of the fire, play in this event?

Who Were The Last Nazis On Trial? – Mythbusting Berlin

More than eighty years after the Holocaust, courtrooms across Germany still echo with testimony from the final chapter of Nazi justice. Centenarian defendants in wheelchairs, their faces hidden behind folders, arrive to answer for crimes committed in their youth. These are not the architects of genocide—those men faced their reckoning at Nuremberg decades ago. These are the guards, the secretaries, the bookkeepers: ordinary people who enabled extraordinary evil. Their trials represent a legal revolution: the

Why Is Berlin The Capital Of Germany? – Mythbusting Berlin

There was little in its humble origins—as a twin trading outpost on a minor European river—to suggest that Berlin was destined for greatness. It sits on the flat expanse of the North European Plain, a landscape once dismissively referred to as the “sandbox of the Holy Roman Empire.” Unlike other world capitals, it lacks breathtaking scenery or a naturally defensible position. It is a city built not on majestic hills or a grand harbour, but