“To drive 600,000 people by robbery into hunger, by hunger into desperation, by desperation into wild outbreaks, and by such outbreaks into the waiting knife—such is the coolly calculated plan. Mass murder is the goal, a massacre such as history has not seen—certainly not since Tamerlane and Mithridates. We can only venture guesses as to the technical forms these mass executions are to take.”

Konrad Heiden, German Jewish author of ‘The New Inquisition’ (1939)

When Soviet forces liberated Auschwitz in January 1945, they discovered mountains of evidence: 7,000 kilograms of human hair, thousands of shoes, and barely alive prisoners. Yet even with such tangible proof, determining precise casualty figures would require decades of meticulous research.

How do historians count the dead when an entire apparatus of state machinery worked to obscure their crimes and erase their victims? When entire communities were erased, when families disappeared together.

The answer lies in one of the most exhaustive documentation projects in modern history—a convergence of captured Nazi documents, demographic analysis, survivor testimony, archaeological evidence, and postwar investigations that collectively paint an irrefutable picture.

The so-called Third Reich, for all its attempts to obscure its crimes through euphemisms like ‘special treatment’ and ‘resettlement’, could not completely destroy the paper trail of its systematic murder program.

We examine how historians have documented the Holocaust’s death toll, the methodology behind the numbers, and the overwhelming weight of evidence that supports current scholarly consensus. This journey traces the evolution of Holocaust documentation from the first wartime revelations through the immediate postwar trials to modern historical scholarship.

As the story of how we know what we know about the Holocaust is, in itself, a testament to historical methodology and the imperative of memory.

–

The European Jewish Community Before The Nazis

“The Jews of Europe were not a monolithic bloc but a wonderfully diverse and creative population, speaking a dozen languages, occupying every rung on the social ladder, and espousing every political and religious creed. Their collective story was not one of impending doom but of remarkable resilience and cultural flourishing.”

Lucy S. Dawidowicz, historian, in ‘The War Against the Jews, 1933-1945’

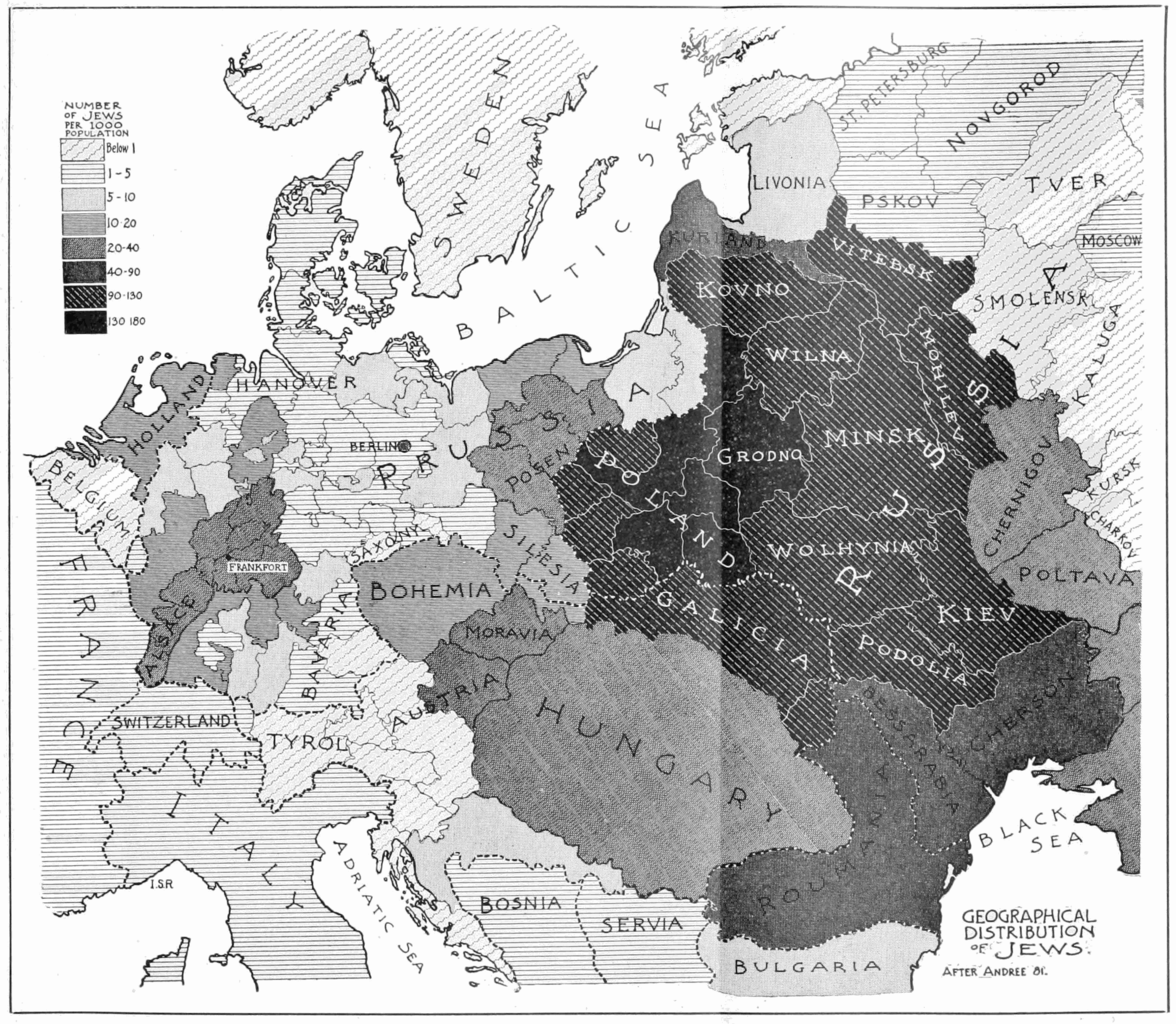

To understand the scale of what was lost, we must first understand what existed.

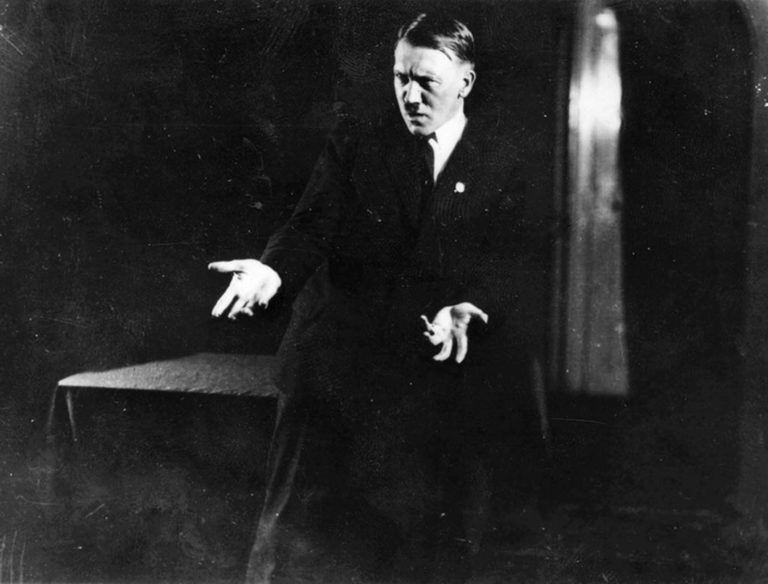

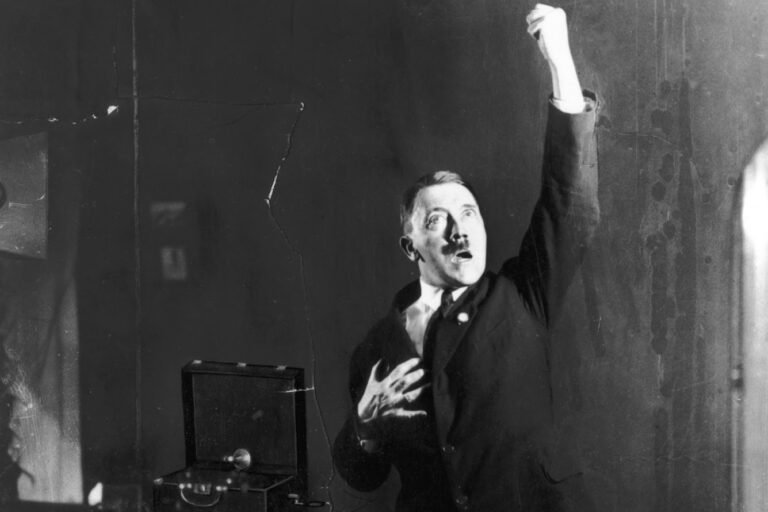

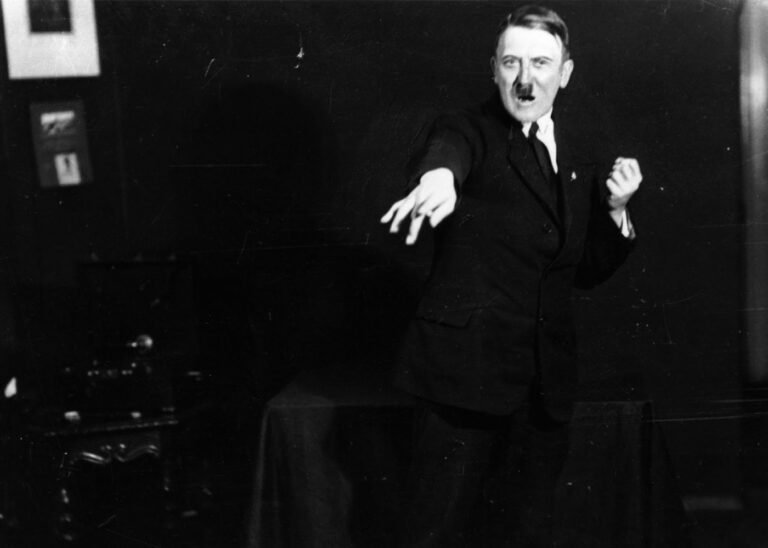

In 1933, when Adolf Hitler became Chancellor of Germany, approximately 560,000 Jews lived in Germany, comprising less than one percent of the population.

Many considered themselves thoroughly integrated into German society—lawyers, doctors, professors, business owners, veterans who had fought for Germany in the First World War. Cities like Berlin, Frankfurt, and Hamburg had vibrant Jewish communities with synagogues, cultural institutions, and deep roots stretching back centuries.

The situation for Jews in Central and Eastern Europe, however, varied considerably.

- In Poland, over three million Jews constituted about ten percent of the population, with large communities in Warsaw, Łódź, Kraków, and Lublin.

- In the Soviet territories that would later fall under Nazi occupation, millions more Jews lived in cities and shtetls.

- In Hungary, Romania, and the Baltic states, substantial Jewish populations had existed for centuries.

These communities kept records.

Jewish organizations documented births, deaths, marriages, and migrations. Census data existed. Synagogue membership rolls were maintained. When these communities were destroyed, the demographic disappearance could be measured.

The Nazi rise to power did not immediately signal genocide.

The early persecution was legal, bureaucratic, and incremental. The Nuremberg Laws of 1935 stripped Jews of citizenship and prohibited marriages between Jews and non-Jews. Jews were progressively excluded from professions, forced out of civil service, and subjected to increasing social ostracism.

By 1939, roughly half of Germany’s Jewish population had emigrated, though many would later be caught in Nazi-occupied territories.

The crucial point for historical documentation is that these communities existed in recorded form.

Prewar censuses, community records, and demographic data provide baseline numbers against which losses can be measured.

The Jews of Europe were not invisible—they were already counted, documented, registered citizens of their respective countries.

Their subsequent disappearance could therefore be quantified.

–

The Concentration Camp System: From Political Repression to Racial Persecution

“The transition from Dachau, the political camp of 1933, to Auschwitz, the death factory of 1943, was not pre-planned. It was an evolution in brutality, a radicalization that grew as the regime’s racial ideology consumed its political objectives.”

Ian Kershaw, historian, in ‘Hitler: A Biography’

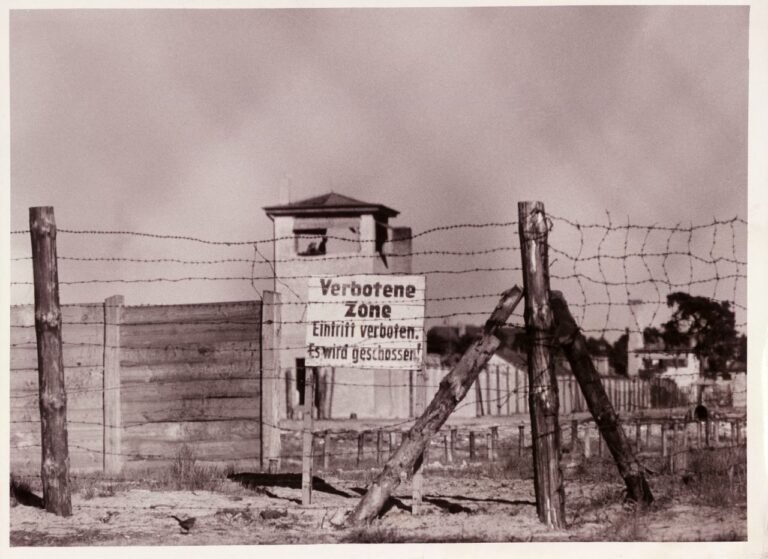

The first concentration camp, Dachau, opened in March 1933, just weeks after Adolf Hitler became German Chancellor.

Initially, concentration camps imprisoned political opponents: communists, social democrats, trade unionists, and others deemed dangerous to the Nazi state.

Jews were among these early prisoners, but they were arrested for their political activities rather than for being Jewish per se. This distinction is important for understanding how Nazi policy evolved.

In the early years, the concentration camp system functioned primarily as a tool of political terror and repression. Camps like Dachau, Sachsenhausen, and Buchenwald held thousands of prisoners under brutal conditions. Many died from mistreatment, forced labour, disease, and outright murder, but the camps were not yet dedicated killing facilities.

Historical estimates suggest several thousand deaths in concentration camps before 1938, with the majority being political prisoners of various backgrounds.

The November Pogrom (referred to as Reichkristallnacht in the Nazi press) that took place on November 9th-10th, 1938, marked a turning point.

Following this organised pogrom, approximately 30,000 Jewish men were arrested and sent to concentration camps—to Dachau, Buchenwald, and Sachsenhausen—specifically because they were Jewish.

This was the first mass imprisonment of Jews by the Nazis as a racial category rather than for political activities. Most were released after weeks or months, provided they agreed to emigrate and transfer their property to the Reich, but several hundred died in custody.

This shift – from imprisoning Jews who were also political opponents to imprisoning Jews simply for being Jewish – represented a critical evolution in Nazi policy. It demonstrated that concentration camps could be used for racial persecution on a mass scale.

The documentation from this period is relatively good: camp records, release documents, and death certificates provide substantial evidence of numbers.

The expansion of concentration camps accelerated after 1939.

With the invasion of Poland, new camps were established in occupied territories.

Auschwitz opened in 1940, initially for Polish political prisoners. Majdanek was established in 1941. The camp system grew exponentially, with hundreds of sub-camps and labour camps spreading across Nazi-controlled Europe.

Between 1933 and 1939, concentration camps killed thousands, but these deaths, while atrocious, were not yet genocide.

The historical documentation from this period includes camp records, survivor testimony, postwar investigations, and perpetrator accounts. Estimates for deaths in concentration camps during this early period range from several thousand to approximately 10,000, with wide variation depending on how ‘concentration camp death’ is defined versus deaths in Gestapo custody, during arrests, or from other forms of persecution.

The point for historical documentation is that the early concentration camp system left substantial records.

The camps operated within German law, twisted though that law was.

Records were kept, prisoners were registered, and deaths were documented.

This bureaucratic impulse would continue even as the killing escalated to genocidal levels.

–

The Invasion of Poland and the Einsatzgruppen: Mass Murder Begins

“The Holocaust did not begin with the gas chambers. It began in the fields and forests of Poland and the Soviet Union, with rifles and machine guns. The Einsatzgruppen were mobile killing units whose task was to murder Jews, intellectuals, and partisans, face-to-face, bullet by bullet. This was murder at its most intimate and brutal.”

Timothy Snyder, historian, in ‘Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin’

When Germany invaded Poland on September 1st 1939, followed by the Soviet invasion from the east on September 17th, Poland’s 3.3 million Jews fell under either Nazi or Soviet control.

The Nazi regime now faced what they called the ‘Jewish question’ on an unprecedented scale.

Initially, policies focused on ghettoisation, exploitation, and plans for eventual ‘resettlement’, but mass murder began almost immediately.

The Einsatzgruppen – mobile killing squads – followed the German army into Poland.

Initially, their targets were Polish elites, intelligentsia, clergy, and potential resistance leaders. However, Jews were killed from the beginning, though not yet systematically. The death toll from the 1939 Polish campaign included thousands of Jews murdered in mass shootings, burned in synagogues, and killed in pogrom-style actions.

The Nazi regime soon established ghettos in major Polish cities.

The Warsaw Ghetto, sealed in November 1940, imprisoned approximately 450,000 Jews in an area of 1.3 square miles. The Litzmannnstadt (Łódź) Ghetto held over 160,000. Smaller ghettos were established in hundreds of towns. Conditions were deliberately lethal: overcrowding, starvation rations, lack of sanitation, and brutal forced labour. People died from disease, starvation, cold, and random violence. The ghettos were both holding pens and killing grounds.

Documentation from the ghetto period is extensive. The Nazis kept detailed records of ghetto populations, food distributions, labor assignments, and deaths. Jewish councils (Judenräte) were forced to maintain population registers.

Chroniclers within the ghettos—notably the Oyneg Shabes archive created by Emanuel Ringelblum in Warsaw—documented conditions, collected testimonies, and buried records for future discovery. These archives were found after the war and provide extraordinary firsthand documentation.

Estimates suggest that hundreds of thousands died in the ghettos from ‘natural causes’—that is, from the deliberately created conditions of starvation, disease, and exposure.

- In the Warsaw Ghetto alone, approximately 100,000 people died before the ghetto was liquidated.

- In Łódź, tens of thousands perished.

- Across all the ghettos in occupied Poland and territories, the death toll from ghetto conditions alone reached several hundred thousand.

The systematic mass shooting of Jews began with Operation Barbarossa, the invasion of the Soviet Union on June 22nd 1941.

The Einsatzgruppen – four main groups with about 3,000 men – followed the German army eastward with explicit orders to kill Soviet political commissars, Communist Party members, and Jews. What began as targeted killings of Jewish men quickly expanded to the murder of entire communities: men, women, children, and elderly.

The scale and methodology of these Einsatzgruppen killings is well-documented because the units filed regular reports to Berlin.

These operational reports, captured after the war, detail killing operations with bureaucratic precision. They specify locations, dates, numbers killed, and methods used.

The reports are not ambiguous: they state clearly “Jews executed: 3,145” or similar figures.

Major massacres include:

- Babi Yar near Kyiv, where 33,771 Jews were murdered over two days in September 1941.

- At Rumbula near Riga, approximately 25,000 Jews were murdered in late 1941.

- In Kaunas, Lithuania, at the Ninth Fort, tens of thousands were killed.

- The Einsatzgruppen and local collaborators moved from town to town, assembling Jewish populations, marching them to pits or ravines, and shooting them.

Wehrmacht units and local collaborators also participated alongside the Einsatzgruppen.

Romanian forces killed tens of thousands of Jews in territories they occupied. Lithuanian, Latvian, and Ukrainian auxiliary police units participated in mass shootings. The killing was not limited to a few SS zealots—it involved thousands of perpetrators.

By the end of 1941, the Einsatzgruppen and their collaborators had murdered approximately 500,000 to 800,000 Jews in occupied Soviet territories. By the end of the war, the total killed in mass shooting operations in the East reached approximately 1.5 to 2 million people, with the vast majority being Jews.

The documentation is overwhelming: Einsatzgruppen reports, Wehrmacht records, Soviet investigations of massacre sites after liberation, testimony from survivors who escaped the pits, perpetrator confessions at postwar trials, and physical evidence from mass graves.

When Soviet forces retook territories, they investigated massacre sites, exhumed mass graves, documented findings, and took testimony.

These Soviet reports, while sometimes used for propaganda, were fundamentally factual in describing what they found.

–

The T4 Programme: Perfecting Industrial Murder

“I considered it my duty to shorten the suffering of these incurable creatures. It was a medical act, a mercy killing. The state had determined that their lives held no value.”

Dr. Karl Brandt, Hitler’s personal physician and a key organizer of the T4 program, during his testimony at the Nuremberg Trials

The technological and methodological bridge between early killings and the industrialised death camps was the T4 euthanasia programme.

In October 1939, Adolf Hitler authorised the killing of Germans with mental and physical disabilities, backdating his written authorisation to September 1st 1939—the start of the war. The programme was named after its Berlin headquarters address: Tiergartenstrasse 4.

The T4 programme was Nazi racial ideology clinically applied to German citizens.

People deemed “life unworthy of life”—those with disabilities, mental illness, or genetic conditions—were systematically murdered. Initially, the method was lethal injection or starvation, but the programme soon developed gas chambers disguised as shower rooms. Carbon monoxide gas from canisters was piped into sealed rooms. Bodies were cremated to eliminate evidence.

Between January 1940 and August 1941, when the programme was officially halted due to public protests, at least 70,000 Germans were murdered in T4 killing centers. The actual number is likely higher, and a decentralised continuation called “wild euthanasia” continued throughout the war, claiming perhaps 200,000 additional victims.

Jewish patients in mental institutions were particularly targeted. Some T4 operations specifically killed Jewish patients first or exclusively. The overlap between anti-disability and antisemitic ideology produced particularly targeted killings of Jews with mental illness or disabilities.

The relevance to Holocaust documentation is methodological and personnel.

While the use of Zyklon B would be later standardised as a result of testing at Auschwitz, the T4 programme perfected the gas chamber as a killing method. It trained personnel in mass murder. It developed the administrative and psychological mechanisms for industrial killing: deception of victims, euphemistic language, cremation to destroy evidence, and bureaucratic distance between decision-makers and killers.

When T4 was officially stopped due to public protest – particularly Bishop von Galen’s sermon – the infrastructure and personnel were redirected to Poland. T4 personnel staffed the Operation Reinhard death camps. The gas chambers that had killed disabled Germans in Hadamar, Brandenburg, Bernburg, Grafeneck, Hartheim, and Sonnenstein became the model for the death camps at Bełżec, Sobibór, and Treblinka.

The documentation for T4 is extensive because it operated within Germany.

Records were kept. Death certificates were issued (with falsified causes). Families were notified of a ‘mercy killing’ (Gnadentod). After the war, these records were discovered, survivors from institutions testified, and perpetrators were tried.

The paper trail of T4 highlights the Nazi regime’s bureaucratic approach to mass murder—an approach that would be applied to the Final Solution.

–

Operation Reinhard and the Death Camps: Industrial Genocide

“Auschwitz-Birkenau has become the symbol of the Holocaust, but the camps of Operation Reinhard—Bełżec, Sobibór, and Treblinka—were different. They were not labor camps with a crematorium attached. They were pure extermination centers. Their sole purpose was to murder Jews as efficiently as possible and erase all traces.”

Yitzhak Arad, historian and survivor, in Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka: The Operation Reinhard Death Camps

On January 20th 1942, fifteen senior Nazi officials met at a villa in Wannsee, a suburb of Berlin, to coordinate the “Final Solution to the Jewish Question.”

The Wannsee Conference did not decide to murder Europe’s Jews – that decision had already been made and killings were well underway – but it coordinated the bureaucratic machinery of genocide across ministries and agencies.

The protocol of the Wannsee Conference survived the war. The document lists Jewish populations in every European country—even neutral countries and British territories—with a total of eleven million Jews marked for extermination. It discusses methods, logistics, and coordination between the SS, civil service, and military authorities. The protocol is a chilling administrative document, discussing mass murder in euphemistic bureaucratic language.

Following Wannsee, the operation to exterminate the Jews of occupied Poland intensified. ‘Operation Reinhard’, named after Reinhard Heydrich (who chaired the Wannsee Conference and was assassinated in June 1942), established three pure extermination camps: Bełżec, Sobibór, and Treblinka. These were not concentration camps with labour functions—they existed solely to kill.

The Operation Reinhard camps pioneered industrial murder.

Victims arrived by train, were told they were at a transit camp, were ordered to undress for showers, and were driven into gas chambers where carbon monoxide from diesel engines asphyxiated them. The process took approximately 20-30 minutes. Bodies were initially buried in mass graves, later exhumed and burned to destroy evidence. Belongings were sorted and shipped to Germany. The entire process, from arrival to death, often occurred within hours.

- Bełżec operated from March to December 1942 and murdered approximately 434,508 people, almost all Jews, with fewer than five known survivors.

- Sobibór operated from May 1942 to October 1943, killed approximately 167,000 people, and had approximately 50 survivors due to the October 1943 uprising.

- Treblinka operated from July 1942 to August 1943, murdered approximately 870,000 people, and had approximately 67 survivors, again due to an uprising.

These numbers are not guesses.

They come from multiple sources: transport records showing how many people were deported to each camp, testimony from the handful of survivors, testimony from perpetrators (including detailed confessions at postwar trials), and Nazi documents including the Höfle Telegram—a 1943 radio message from SS-Sturmbannführer Hermann Höfle reporting exact numbers of Jews processed through Operation Reinhard camps. The telegram, decrypted by British intelligence, was discovered decades after the war and precisely corroborates other evidence.

Auschwitz-Birkenau requires separate discussion because of its dual function and massive scale. Auschwitz was a concentration camp complex near Oświęcim, Poland, comprising three main camps and dozens of sub-camps. Auschwitz I was the main camp. Auschwitz II-Birkenau was the extermination center. Auschwitz III-Monowitz was a slave labor camp serving I.G. Farben.

Birkenau was equipped with four gas chamber and crematorium complexes. Unlike the Operation Reinhard camps that used carbon monoxide, Birkenau used Zyklon B, a cyanide-based pesticide.

The gas chambers could kill approximately 2,000 people at a time. The crematoriums could dispose of approximately 4,400 bodies per day, though the Nazis also burned bodies in open pits during peak killing periods in 1944.

Auschwitz-Birkenau murdered approximately 1.1 million people, with about one million being Jews. The camp also killed Roma, Polish political prisoners, Soviet POWs, and others. The majority of victims were never registered as camp inmates—they were taken directly from the railway platform to the gas chambers in a process called “selection.” Those deemed fit for labor were tattooed and registered; those deemed unfit (children, elderly, sick, mothers with children) were immediately murdered.

The documentation for Auschwitz is extensive. The camp kept detailed records of registered prisoners, though these records were incomplete and many were destroyed before liberation. Rudolf Höss, the commandant, testified extensively at postwar trials, providing detailed descriptions of the killing process and his estimate of total victims. The camp construction office records, blueprints of the gas chambers and crematoria, orders for Zyklon B, and capacity calculations all survived.

Testimony from survivors is also voluminous. Unlike the Operation Reinhard camps where almost no one survived, tens of thousands survived Auschwitz because it combined extermination with forced labour. Sonderkommando prisoners – Jews forced to work in the gas chambers and crematoria – kept diaries that were buried and later discovered. Members of the Sonderkommando uprising in October 1944 left testimonies. Camp resistance compiled lists and smuggled information out.

The other major death camps were Chelmno, which operated from December 1941 and used gas vans to murder approximately 152,000 people, and Majdanek, which functioned as both a concentration camp and killing center, murdering approximately 78,000 people including 59,000 Jews.

In total, the six death camps—Auschwitz-Birkenau, Treblinka, Bełżec, Sobibór, Chelmno, and Majdanek—murdered approximately 2.7 to 3 million Jews.

This figure comes from converging evidence: transport records showing deportations to these camps, camp documents, testimony from the small number of survivors, perpetrator testimony, and demographic analysis of Jewish communities that disappeared entirely.

–

Death Marches, Slave Labour, and Attrition

“In the last months of the war, the camp system collapsed into a maelstrom of chaos and death. The death marches were the final, desperate act of a regime determined to leave no witnesses and to work its prisoners to death until the very end. It was genocide by exhaustion.”

Richard Overy, historian, in ‘The Dictators: Hitler’s Germany and Stalin’s Russia’

The death camps account for roughly half of Jewish Holocaust deaths.

The remainder died from the cumulative effects of ghettoisation, forced labor, death marches, shootings, starvation, disease, and deliberate neglect.

As the war turned against Germany and Soviet forces advanced from the east, the Nazis evacuated concentration camps and forced prisoners on death marches. These were forced marches in winter, often hundreds of kilometers, with no food, inadequate clothing, and anyone who fell behind was shot.

The most extensive death marches occurred in January 1945 as camps in Poland were evacuated ahead of Soviet forces.

Approximately 250,000 to 375,000 people died on death marches in the final months of the war. These deaths are documented through survivor testimony, records of prisoners evacuated from camps versus those found at liberation, and the discovery of bodies along march routes.

Forced labour was a slower form of murder. Jews and others were worked to death in armaments factories, construction projects, mines, and quarries. The concept of “annihilation through labor” (Vernichtung durch Arbeit) was an explicit Nazi policy. Prisoners received starvation rations, worked 12-hour days in brutal conditions, had no medical care, and were murdered when they became too weak to work.

The number who died from forced labor is difficult to calculate precisely but estimates range from several hundred thousand to over half a million. This includes Jews forced into labor before being sent to death camps, those who died in labor camps, and those who survived until liberation but died shortly after from the effects of their treatment.

Deaths during transport must also be counted. Jews were transported to death camps in sealed freight cars, often over 100 people per car, with no water, food, sanitation, or ventilation. The journey could take days.

Many died during transport, particularly the young, elderly, and infirmed. Estimates suggest tens of thousands died in transport.

The cumulative death toll from all these factors—ghettos, forced labor, death marches, transport, and deliberate neglect—adds approximately 2.5 to 3 million deaths to the toll from gas chambers and mass shootings.

–

Counting the Dead: Historical Methodology

“The perpetrators left behind a mountain of paper. Their bureaucracy, their obsession with detail, gave us the very documents we needed to trace the path of destruction. We can count the trainloads, read the orders, and analyze the inventories. The German record is the primary indictment.”

Raul Hilberg, a foundational scholar of the Holocaust, in ‘The Destruction of the European Jews’

Taken together, all these avenues of atrocity lead to approximately six million Jewish deaths.

How have historians arrived at this figure? The methodology is complex, drawing on multiple independent sources of evidence that corroborate each other.

Demographic Analysis: The primary method is comparing prewar and postwar Jewish populations.

- Prewar census data from European countries documented Jewish populations. Postwar censuses and surveys documented survivors. The difference represents deaths and emigration. By accounting for emigration (records of which largely exist), researchers can calculate deaths.

- The American Jewish Year Book and other Jewish organizations compiled population statistics. In 1939, approximately 9.5 million Jews lived in Europe. By 1945, approximately 3.5 million survived. Accounting for emigration before and during the early war years, the death toll is approximately 5.7 to 6 million.

Nazi Documents: While the Nazis destroyed many records as the war ended, enormous numbers of documents survived. The Allies captured tons of documents, which were used in postwar trials and are now in archives worldwide. These include:

- Transport records showing numbers deported to camps and ghettos

- Einsatzgruppen operational reports documenting mass shootings

- Camp records of registered prisoners and deaths

- The Höfle Telegram reporting Operation Reinhard deaths

- Correspondence between Nazi officials discussing numbers

- Wannsee Conference protocol listing target populations

- Commandant reports on camp capacity and operations

Postwar Investigations and Trials: The Nuremberg Trials, subsequent trials in multiple countries, and ongoing investigations have compiled vast amounts of evidence. Perpetrators testified, often trying to minimize their roles but confirming the basic facts. Camp personnel, Einsatzgruppen members, and civil servants involved in deportations provided detailed testimony.

The Eichmann trial in Jerusalem in 1961 produced extensive documentation. West German prosecutors conducted hundreds of trials. Soviet prosecutors investigated massacre sites and gathered evidence. These investigations cross-referenced documents, testimony, and physical evidence.

Survivor Testimony: Millions of survivors provided testimony—immediately after liberation, in war crimes trials, in compensation claims, in oral history projects. Testimony from individual survivors might be fragmented or contain errors, but the collective testimony from thousands of survivors from different camps, ghettos, and regions forms a consistent picture.

Survivors of the Sonderkommando, who worked in the gas chambers, provided eyewitness accounts of the murder process. Survivors of labor camps described conditions. Survivors of death marches described routes and atrocities.

Physical Evidence: Mass graves across Eastern Europe contain the physical evidence of mass shootings. Archaeological investigations have located and documented these sites. The remains of gas chambers, though partially destroyed by the Nazis, still exist at Auschwitz, Majdanek, and in ruins at other camps. The railway infrastructure used for deportations remains.

Contemporary aerial reconnaissance photographs taken by Allied aircraft show the camp complexes, including people entering gas chambers at Auschwitz. These photographs, not analyzed for this purpose until years later, provide contemporaneous visual evidence.

Statistical Methods: Modern demographic research uses sophisticated statistical methods. The Yad Vashem Central Database of Shoah Victims’ Names has collected names of over 4.8 million Jewish Holocaust victims. The database includes multiple types of documentation for each person, cross-referenced to eliminate duplicates.

The convergence of these independent sources provides confidence in the figures. The demographic analysis gives approximately 5.7 to 6 million.

Tallying death camp victims, Einsatzgruppen shootings, ghetto deaths, death march deaths, and other causes from documented sources gives approximately 5.5 to 6.2 million. The overlap between these completely different methodologies confirms the accuracy of estimates.

Regional Breakdowns: Historians have calculated deaths by country:

- Poland: Approximately 3 million (90% of prewar population)

- Soviet territories: Approximately 1.5 million

- Hungary: Approximately 560,000

- Romania: Approximately 280,000

- Germany and Austria: Approximately 210,000

- Netherlands: Approximately 105,000

- France: Approximately 75,000

- Czechoslovakia: Approximately 260,000

- Yugoslavia: Approximately 65,000

- Greece: Approximately 65,000

- Belgium: Approximately 28,000

- Italy: Approximately 7,500

- Other countries: Approximately 130,000

These figures are derived from country-specific research using local records, deportation documents, and postwar census data.

The sum of country-by-country calculations aligns with overall demographic analysis.

–

Conclusion

“The opposite of love is not hate, it’s indifference. The opposite of art is not ugliness, it’s indifference. The opposite of faith is not heresy, it’s indifference. And the opposite of life is not death, it’s indifference. That is what the world showed us.”

Elie Wiesel, Holocaust survivor and Nobel laureate

How many Jews died in the Holocaust? The honest historical answer is: approximately six million. The current scholarly consensus places the figure between 5.7 and 6.2 million, with most estimates centering around 6 million.

The uncertainty of several hundred thousand either way results from incomplete records, particularly for the Einsatzgruppen killings in the East and deaths from disease and starvation in ghettos.

This uncertainty does not undermine the historical reality—it reflects normal historical limitations in documenting events of such magnitude. We don’t know precisely how many Romans died in the eruption of Vesuvius, or exactly how many people died in the Black Death, or precisely how many casualties resulted from Hiroshima. Historical precision has limits,but it does not in any way provide fundament for questioning the veracity of the event itself nor its volume.

What we do know with absolute certainty:

- The Nazi regime pursued a systematic policy to murder all Jews within their reach

- They succeeded in murdering approximately two-thirds of European Jews

They employed multiple methods: shootings, gassing, starvation, and working people to death - They constructed an industrial apparatus specifically designed for mass murder

- Approximately six million Jews were murdered

The evidence for this is overwhelming and comes from multiple independent sources

The arithmetic of atrocity will always be a controversial subject – the effort to establish precise numbers, however, is not pedantry—it is an act of commemoration and justice. Each number represents a person, a life, a story.

Contrary to the saying – often incorrectly attributed to Joseph Stalin, that the death of one is a tragedy while the death of millions is just a statistic – the death of millions is millions upon millions of tragedies compounded. The connections never made, the experiences never shared, the loss felt by friends, family, and those who had not yet even been met.

Whether eventually 5,999,999 or 6,000,00, each person within this mass is too many.

The number matters because each person mattered – individual human beings, each with a name, a family, a life that was stolen.

And we count, document, and remember because to forget would be a second death.

***

If you’ve enjoyed reading this article, consider booking one of our private guided tours of Berlin.

Bibliography

Aly, Götz. Hitler’s Beneficiaries: Plunder, Racial War, and the Nazi Welfare State. New York: Metropolitan Books, 2007.

Aly, Götz, and Susanne Heim. Architects of Annihilation: Auschwitz and the Logic of Destruction. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2002.

Arad, Yitzhak. Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka: The Operation Reinhard Death Camps. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1987.

Arad, Yitzhak. The Holocaust in the Soviet Union. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2009.

Bartov, Omer. The Eastern Front, 1941-45: German Troops and the Barbarisation of Warfare. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2001.

Bauer, Yehuda. A History of the Holocaust. New York: Franklin Watts, 2001.

Bauer, Yehuda. Rethinking the Holocaust. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001.

Berenbaum, Michael. The World Must Know: The History of the Holocaust as Told in the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1993.

Benz, Wolfgang. The Holocaust: A German Historian Examines the Genocide. New York: Columbia University Press, 1999.

Blatman, Daniel. The Death Marches: The Final Phase of Nazi Genocide. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2011.

Bloxham, Donald. The Final Solution: A Genocide. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.

Braham, Randolph L. The Politics of Genocide: The Holocaust in Hungary. New York: Columbia University Press, 1994.

Breitman, Richard. The Architect of Genocide: Himmler and the Final Solution. New York: Knopf, 1991.

Browning, Christopher R. The Origins of the Final Solution: The Evolution of Nazi Jewish Policy, September 1939-March 1942. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2004.

Browning, Christopher R. Ordinary Men: Reserve Police Battalion 101 and the Final Solution in Poland. New York: HarperCollins, 1992.

Browning, Christopher R. Remembering Survival: Inside a Nazi Slave Labor Camp. New York: W.W. Norton, 2010.

Burleigh, Michael. Death and Deliverance: ‘Euthanasia’ in Germany 1900-1945. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994.

Cesarani, David. Final Solution: The Fate of the Jews 1933-1949. London: Macmillan, 2016.

Czech, Danuta. Auschwitz Chronicle, 1939-1945. New York: Henry Holt, 1990.

Dawidowicz, Lucy S. The War Against the Jews, 1933-1945. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1975.

Dean, Martin. Robbing the Jews: The Confiscation of Jewish Property in the Holocaust, 1933-1945. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

Dwork, Deborah, and Robert Jan van Pelt. Auschwitz: 1270 to the Present. New York: W.W. Norton, 1996.

Dwork, Deborah, and Robert Jan van Pelt. Holocaust: A History. New York: W.W. Norton, 2002.

Engelking, Barbara, and Jacek Leociak. The Warsaw Ghetto: A Guide to the Perished City. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009.

Evans, Richard J. The Third Reich at War. New York: Penguin Press, 2009.

Friedländer, Saul. The Years of Extermination: Nazi Germany and the Jews, 1939-1945. New York: HarperCollins, 2007.

Friedländer, Saul. Nazi Germany and the Jews, 1933-1939: The Years of Persecution. New York: HarperCollins, 1997.

Friedlander, Henry. The Origins of Nazi Genocide: From Euthanasia to the Final Solution. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1995.

Gilbert, Martin. The Holocaust: A History of the Jews of Europe During the Second World War. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1985.

Gilbert, Martin. Atlas of the Holocaust. New York: William Morrow, 1993.

Goldhagen, Daniel Jonah. Hitler’s Willing Executioners: Ordinary Germans and the Holocaust. New York: Knopf, 1996.

Grabowski, Jan. Hunt for the Jews: Betrayal and Murder in German-Occupied Poland. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2013.

Greif, Gideon. We Wept Without Tears: Testimonies of the Jewish Sonderkommando from Auschwitz. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005.

Gross, Jan T. Neighbors: The Destruction of the Jewish Community in Jedwabne, Poland. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001.

Gutman, Israel, ed. Encyclopedia of the Holocaust. 4 vols. New York: Macmillan, 1990.

Hayes, Peter. Why? Explaining the Holocaust. New York: W.W. Norton, 2017.

Hayes, Peter. Industry and Ideology: IG Farben in the Nazi Era. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987.

Hilberg, Raul. The Destruction of the European Jews. 3rd ed. 3 vols. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003.

Hilberg, Raul. Perpetrators Victims Bystanders: The Jewish Catastrophe 1933-1945. New York: HarperCollins, 1992.

Höss, Rudolf. Death Dealer: The Memoirs of the SS Kommandant at Auschwitz. Edited by Steven Paskuly. Buffalo: Prometheus Books, 1992.

Kaplan, Marion A. Between Dignity and Despair: Jewish Life in Nazi Germany. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Karski, Jan. Story of a Secret State: My Report to the World. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1944.

Kershaw, Ian. Hitler, the Germans, and the Final Solution. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008.

Kogon, Eugen. The Theory and Practice of Hell: The German Concentration Camps and the System Behind Them. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2006.

Kwiet, Konrad. Reichskommissariat Niederlande: Versuch und Scheitern nationalsozialistischer Neuordnung. Stuttgart: Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, 1968.

Lanzmann, Claude. Shoah: The Complete Text of the Acclaimed Holocaust Film. New York: Da Capo Press, 1995.

Levi, Primo. Survival in Auschwitz. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996.

Levine, Paul A. From Indifference to Activism: Swedish Diplomacy and the Holocaust, 1938-1944. Uppsala: Uppsala University, 1996.

Lifton, Robert Jay. The Nazi Doctors: Medical Killing and the Psychology of Genocide. New York: Basic Books, 1986.

Lipstadt, Deborah E. Denying the Holocaust: The Growing Assault on Truth and Memory. New York: Free Press, 1993.

Longerich, Peter. Holocaust: The Nazi Persecution and Murder of the Jews. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Longerich, Peter. Heinrich Himmler. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Lower, Wendy. Nazi Empire-Building and the Holocaust in Ukraine. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005.

Manoschek, Walter, ed. Die Wehrmacht im Rassenkrieg: Der Vernichtungskrieg hinter der Front. Vienna: Picus Verlag, 1996.

Marcuse, Harold. Legacies of Dachau: The Uses and Abuses of a Concentration Camp, 1933-2001. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001.

Marrus, Michael R., and Robert O. Paxton. Vichy France and the Jews. New York: Basic Books, 1981.

Matthäus, Jürgen, and Frank Bajohr, eds. The Political Diary of Alfred Rosenberg and the Onset of the Holocaust. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2015.

Megargee, Geoffrey P., ed. The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1933-1945. 3 vols. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2009-2018.

Müller, Filip. Eyewitness Auschwitz: Three Years in the Gas Chambers. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 1979.

Novick, Peter. The Holocaust in American Life. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1999.

Piper, Franciszek. Auschwitz: How Many Perished Jews, Poles, Gypsies…. Kraków: Poligrafia ITS, 1992.

Pressac, Jean-Claude. Auschwitz: Technique and Operation of the Gas Chambers. New York: Beate Klarsfeld Foundation, 1989.

Rhodes, Richard. Masters of Death: The SS-Einsatzgruppen and the Invention of the Holocaust. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2002.

Ringelblum, Emanuel. Notes from the Warsaw Ghetto: The Journal of Emmanuel Ringelblum. Edited by Jacob Sloan. New York: Schocken Books, 1958.

Roseman, Mark. The Wannsee Conference and the Final Solution: A Reconsideration. New York: Metropolitan Books, 2002.

Rückerl, Adalbert. NS-Vernichtungslager im Spiegel deutscher Strafprozesse. Munich: Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, 1977.

Sereny, Gitta. Into That Darkness: An Examination of Conscience. New York: Vintage Books, 1983.

Shermer, Michael, and Alex Grobman. Denying History: Who Says the Holocaust Never Happened and Why Do They Say It?. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000.

Snyder, Timothy. Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin. New York: Basic Books, 2010.

Sofsky, Wolfgang. The Order of Terror: The Concentration Camp. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997.

Steinbacher, Sybille. Auschwitz: A History. Munich: Verlag C.H. Beck, 2004.

Stone, Dan, ed. The Historiography of the Holocaust. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004.

Trunk, Isaiah. Judenrat: The Jewish Councils in Eastern Europe Under Nazi Occupation. New York: Macmillan, 1972.

van Pelt, Robert Jan. The Case for Auschwitz: Evidence from the Irving Trial. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2002.

Wachsmann, Nikolaus. KL: A History of the Nazi Concentration Camps. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2015.

Weinberg, Gerhard L. A World at Arms: A Global History of World War II. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994.

Wette, Wolfram. The Wehrmacht: History, Myth, Reality. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2006.

Wiesel, Elie. Night. New York: Hill and Wang, 2006.

Yahil, Leni. The Holocaust: The Fate of European Jewry, 1932-1945. New York: Oxford University Press, 1990.

Zimmerman, Joshua D., ed. Contested Memories: Poles and Jews During the Holocaust and Its Aftermath. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2003.

HISTORICAL ARTICLES

Mythbusting Berlin

Are There Any Nazi Statues Left In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

Visitors to Berlin often arrive expecting to find the physical remnants of the tyranny of the 20th century still standing – statues of dictators, triumphal arches, or bronze idols. Instead, they often find none. The stone symbols and statues of the Third Reich are still gazing down on them, however, hiding in plain sight. But why are there no statues of Hitler? Did the Allies destroy them all in 1945, or is the truth stranger

Could The Western Allies Have Captured Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

To contemplate a Western Allied capture of Berlin in 1945 is to challenge the established endgame of the Second World War. What was the true military and logistical feasibility of a Western Allied assault on the Nazi capital? What factors truly sealed Berlin’s fate, and what might have changed had the Allies pushed eastward?

Answering these questions means delving into the complex interplay of logistics, political maneuvering, and the competing visions for a post-war world

Did Any Of The Rothschild Dynasty Die In The Holocaust? – Mythbusting Berlin

The Rothschild name is synonymous with immense wealth, influence, and persistent conspiracy theories—especially during the era of Nazi Germany. Often targeted by antisemitic propaganda, the family’s survival during World War II has sparked myths about their supposed immunity from Nazi persecution. But did any Rothschild family member actually perish in the Holocaust? This article explores that compelling question, unraveling historical misconceptions and revealing the reality behind one of Europe’s most famous dynasties.

Did Frederick The Great Introduce The Potato To Germany? – Mythbusting Berlin

One of the more bizarre claims to fame attributed to the first King of Prussia is that the man who would go down in history known as Frederick the Great introduced the potato to Germany during his reign back in the 1700s. This starchy root vegetable has undoubtedly become a staple part of German cuisine – an essential addition to any plate of Schnitzel, Schweinshaxn, and Königsberger Klopse – however, whether Frederick the Great is

Did Hitler Escape To Argentina In 1945? – Mythbusting Berlin

Although Nazi leader, Adolf Hitler, certainly remains an inescapable figure, could there be any truth to the story of his escape to Argentina in 1945? That the most wanted man on earth could simply vanish, to spend the rest of his life peacefully in South American obscurity captivates imaginations. Yet, despite numerous investigations, this tale persists primarily as myth—fueled by speculation, hearsay, and conspiracy theories.

Did Hugo Boss Design The Nazi Uniforms? – Mythbusting Berlin

The idea that Hugo Boss – the man whose name now adorns expensive suits and fragrances – was the creative genius behind the Nazi uniforms suggests a terrifying collision of haute couture and holocaust – a marriage of high style and high crimes. The image is striking: a German tailor sketching the ultimate villain’s costume. But history, as usual, is far messier, more bureaucratic, and more banal than the internet memes suggest. To understand who

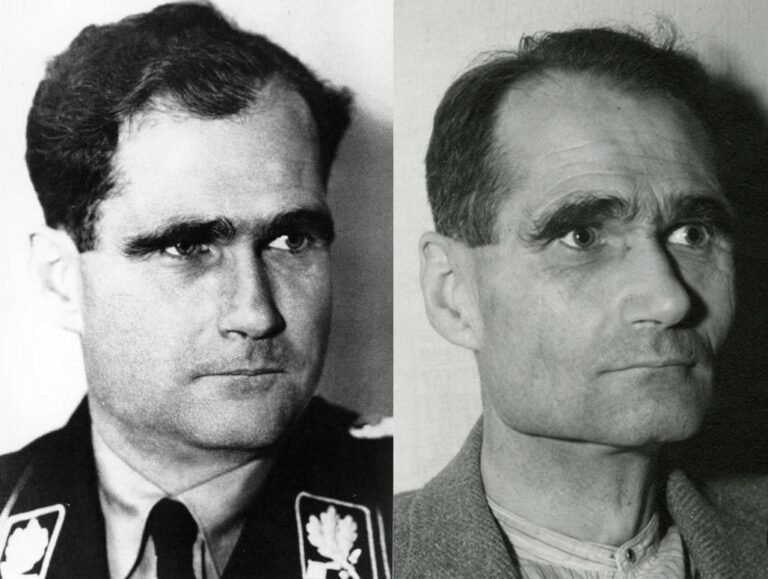

Did Rudolf Hess Really Commit Suicide? – Mythbusting Berlin

On a summer’s day in 1987, the last Nazi war criminal of the Nuremberg trials was found dead in a prison built for hundreds, yet for two decades, housed only him. The official verdict was suicide, a straightforward end to a life defined by fanaticism, delusion, and contradiction.

But the simplicity of the report belied the complexity of the man and the 46 years he had spent in Allied custody. In the meticulously controlled

Did The Nazis Develop Nuclear Weapons? – Mythbusting Berlin

The Nazi obsession with super-weapons became so serious in the closing stages of the Second World that Adolf Hitler personally believed that such ‘Wunderwaffen’ both existed in a usable form – and would save the country from defeat. Had the Nazis managed to develop nuclear weapons by 1945 – the outcome of the war would surely have been different. But how close were Hitler, Himmler, and his henchmen to developing an A-bomb?

Did The Nazis Invent Decaf Coffee? – Mythbusting Berlin

Persistent rumors claim that Nazis preferred their coffee anything but pure, leading some to wonder if they might have influenced the development of decaffeinated coffee. Although decaf was already widely available across Europe by the mid-20th century, speculation continues: could the Nazis really have played a role in popularizing—or even discovering—this caffeine-free alternative, or is this simply another caffeinated conspiracy cooked up to sensationalize an ordinary historical detail?

Did The Nazis Invent The Bicycle Reflector? – Mythbusting Berlin

The fruits of wartime ingenuity are plenty – so many, in-fact, that it has become somewhat of a worn cliche that as the guns start firing the innovators get to work, often solving problems while providing more problems for the enemy to overcome.The kind of progress that results in the production of newer improved, more lethal weapons, such as to increase the chances of victory.

Did The Nazis Run The Largest Counterfeiting Operation In History? – Mythbusting Berlin

During the Second World War the Nazis masterminded an astonishing plot to destabilise Britain by flooding its economy with counterfeit banknotes. Crafted in secret by concentration camp prisoners, this forged fortune became the most ambitious counterfeiting operation ever attempted. But was it history’s largest? Dive into the extraordinary tale of Operation Bernhard,

rife with deception, survival, and intrigue—revealing the truth behind one of the Third Reich’s most audacious schemes and its surprising legacy.

Did The Second World War End In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

When is a war ever truly over? When the last shot is fired in anger would seem like the best measure. Rarely, though, is it possible to gain insight into such a moment.

Remarkably, a record still exists of such a moment at the end of the First World War on the Western Front. A seismic register and recording of the last belching battery of British guns firing artillery across no-man’s-land, followed by a profound

Did The Spanish Flu Pandemic Help The Nazis Take Power? – Mythbusting Berlin

The devastating Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918-1919 struck amid Germany’s post-war turmoil, compounding social instability, economic hardship, and widespread political disillusionment. Could this catastrophic health crisis have indirectly paved the way for Nazi ascension? While often overshadowed by war and revolution, the pandemic’s profound psychological and societal impacts arguably contributed to the perfect storm, enabling extremist ideologies—including Nazism—to gain popularity and ultimately seize power in a fractured Germany.

Have Adolf Hitler’s Remains Been DNA Tested? – Mythbusting Berlin

In the smouldering ruins of Berlin in 1945, the world’s most wanted man vanished. Did Adolf Hitler, as official history attests, die by his own hand in the Führerbunker? Or did he escape, fuelling a thousand conspiracy theories that have echoed for decades? For years, the Soviets claimed to hold the gruesome proof of his death: a skull fragment and a set of teeth, locked away in Moscow archives. But in an age of definitive

How Did The Nazi Concentration Camps Differ From The Soviet GULAG?

The Nazi concentration camps and Soviet Gulag system have often been conflated in popular imagination—twin symbols of twentieth-century totalitarian horror. Yet the two systems operated on fundamentally different principles. One extracted labor to fuel industrialisation while accepting mass death as collateral damage; the other evolved into purpose-built machinery of genocide. Understanding these distinctions isn’t merely academic—it reveals how different ideologies produce different atrocities, and why Germany and Russia reckon with these legacies so differently today.

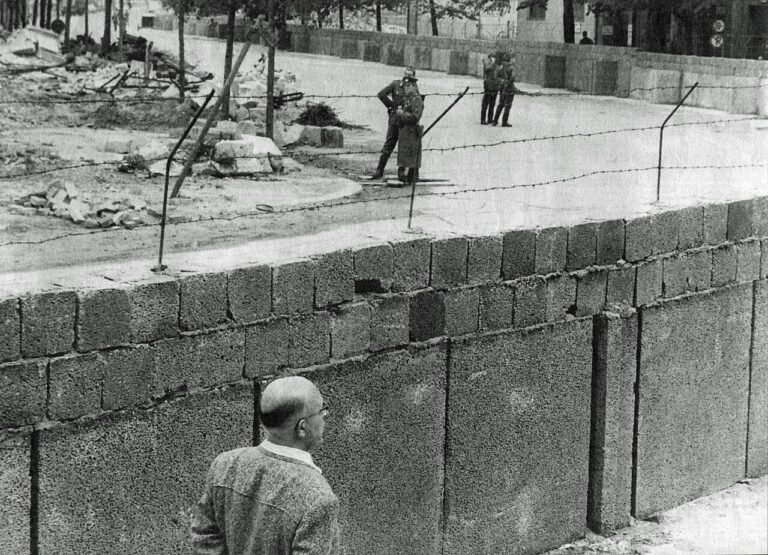

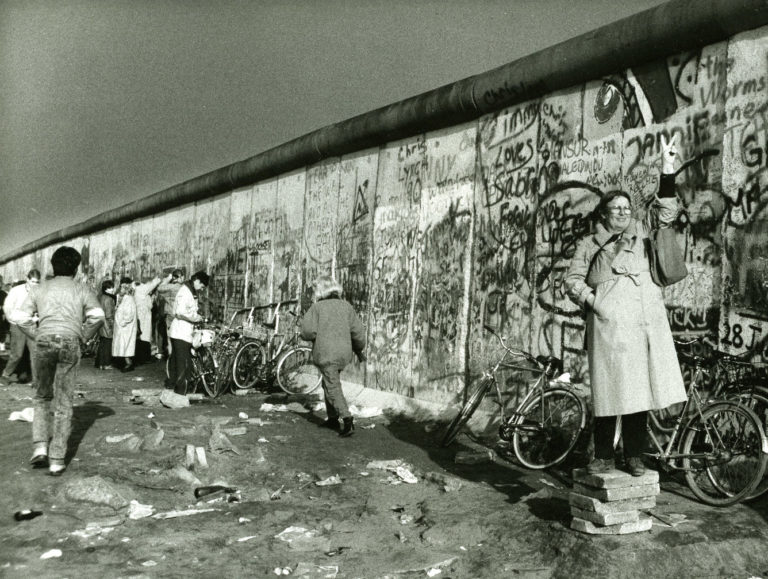

How Long Did It Take To Build The Berlin Wall? – Mythbusting Berlin

It is one of the most enduring images of the 20th century: a city divided overnight. The popular narrative tells us that Berliners went to sleep in a unified city and woke up in a prison. While the shock of August 13th 1961, was very real, the idea that the ‘Wall’ appeared instantly is a historical illusion. The physical scar that bisected Berlin was not a static creation, but a living, malevolent beast that evolved

How Many Assassination Attempts On Adolf Hitler Were There? – Mythbusting Berlin

Nazi leader, Adolf Hitler, projected an aura of invincibility, a man of destiny shielded by providence. But behind the carefully constructed image of the untouchable Führer lies a story of constant threat, of bombs that failed to detonate, and errant bullets that missed their mark. Unearth the hidden history of the numerous attempts on Hitler’s life as we explore the courage of those who tried to change the course of history and the devil’s luck

How Many Jews Died In The Holocaust? – Mythbusting Berlin

The answer to the question posed of how many Jews died in the Holocaust is a simple one: too many. That merely one death was an unforgivable obscenity is a fundamental and necessary realisation in understanding the capriciousness of this unparalleled racial genocide. To comprehend, however, the full number of Jews murdered in Europe by the Nazi regime in the 1930s and 1940s is a detective story of epic proportions: the evidence overwhelming, multifaceted, and

How Many People Died Trying To Escape East Germany? – Mythbusting Berlin

The image of the Berlin Wall is seared into our collective memory, a concrete symbol of Cold War oppression. We think of the daring escapes and the tragic deaths of those who failed. But that well-known number is only a fraction of the truth. The story of those who died trying to escape East Germany is far broader and more complex than most imagine, stretching along a thousand-kilometer border and out into the cold waters

How Old Is Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

A relatively new arrival in Europe, Berlin is over 1000 years younger than London, nevermind Rome or Athens, Jerusalem or Jericho. Just how old is Berlin though?

A question fraught with false assumptions and distortions – that has more often than not been answered with propaganda as it has with the cold hard truth.

Was Adolf Hitler A Drug Addict? – Mythbusting Berlin

Solving the enigma of the ‘Führer’ has become a preoccupation for many, since the arrival of the Austrian-German onto the world stage – although moving beyond the mythology without falling into the trap of prejudically extrapolating on the psychopathography of Hitler or demonising so as to excuse his actions has proven problematic. What to make of the man who became more than the sum of his masks? The painter; the military dilettante, the mass murderer,

Was Adolf Hitler A Freemason? – Mythbusting Berlin

History abhors a vacuum, but adores a mystery. Such is the speculative fiction suggesting a secret allegiance behind the rise of the Third Reich – that the catastrophe of the Second World War was orchestrated from the shadows of a Masonic lodge. The image of Adolf Hitler—the drifter from Vienna turned dictator—as a covert initiate of the very brotherhood he publicly reviled, however, creates a paradox that collapses under scrutiny. As when we unlock the

Was Adolf Hitler Gay? – Mythbusting Berlin

In the shadowy corridors of Third Reich history, few questions provoke as much tabloid curiosity and scholarly exasperation as the sexuality of Adolf Hitler. For decades, rumors have swirled—whispered by political enemies in 1930s Munich, psychoanalyzed by American spies in the 1940s, and sensationalized by revisionist authors today. Was the dictator who condemned thousands of men to concentration camps for “deviant” behavior hiding a secret of his own? By peeling back the layers of propaganda,

Was Adolf Hitler Jewish? – Mythbusting Berlin

Was the dictator who orchestrated the murder of millions of European Jews secretly one of them? It is perhaps the darkest irony imaginable, a story whispered for decades in backrooms, bars, and conspiracy forums alike. The most-common rumour – the ‘Frankenberger Myth’ – suggests that Adolf Hitler’s paternal grandfather was Jewish, a secret so damaging it could have unraveled the entire Nazi regime. But where does this claim come from? And, more importantly, is there

Was Currywurst Invented In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

Explore the story behind what many consider Berlin’s most iconic snack—the ever-so-humble Currywurst. Often hailed as an enduring symbol of culinary creativity amid Cold War scarcity, this humble dish has inspired fierce debate about its true origin. But was it genuinely invented here in Berlin, or have proud locals simply adopted and elevated this spicy street-food favorite into legendary status all their own?

Was Fanta Invented By The Nazis? – Mythbusting Berlin

As one of the most secretive organisations in the world, the Coca Cola corporation refuses to share its secret recipe with anyone. Famously insisting only on shipping the base syrup of its drinks to plants around the world to be carbonated and distributed.

This combined with the trade limitations of the Second World War may have led to the introduction of one of the most popular soft-drinks in the world. But could it be true:

Was Frederick The Great Gay? – Mythbusting Berlin

Frederick II of Prussia, better known as Frederick the Great, is often remembered as the archetypal enlightened monarch – a brilliant military commander, patron of the arts, and learned philosopher. Yet behind the stern portraits of this 18th-century warrior-king lies a personal life long shrouded in intrigue and speculation. Intrigue around the king’s sexual orientation has persisted through the centuries, chiefly revolving around one question: Was Frederick the Great gay?

Was Henry Ford A Nazi? – Mythbusting Berlin

US auto tycoon, Henry Ford, holds the ignominious distinction of being the only American Adolf Hitler praised by name in his National Socialist manifesto: ‘Mein Kampf’. This was not, as it turns out, the only connection between Ford and the Party of Hitler, Himmler, and the Holocaust.

Ford’s overt affinity with the Third Reich reveals a troubling past. How deep these connections ran, and how consequential they were for both sides, is a chapter

Was The Colour Blue Invented In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

Tracing the true history of blue—from ancient Egyptian dyes to the accidental discovery of Prussian Blue in a Berlin lab. We’ll debunk myths about seeing blue, explore colonial indigo plantations, scale mountains with a cyanometer, and trace Van Gogh’s starry skies—all to answer one question: how did Berlin shape our understanding of the world’s rarest color?

Was The Döner Kebab Invented In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

Unlikely icon of immigrant success; fast food symbol of the working class; over-hyped midnight disco eat; or culturally appropriated cuisine? Its influence goes far beyond layers of seasoned meat and fresh vegetables stuffed into pita bread. But does Berlin deserve credit as the Döner Kebab’s true birthplace, or has the city merely refined and popularized a culinary tradition imported from elsewhere?

Was The Fall Of The Berlin Wall An Accident? – Mythbusting Berlin

On a seasonally crisp night in November 1989, one of the most astonishing events of the 20th century occurred. After twenty eight years, three months, and twenty eight days of defining and dividing the German capital, the Berlin Wall ceased to exist – at least in an abstract sense. Although the removal of this symbol of the failure of the East German system would take some time, its purpose – as a border fortification erected

Was The Nazi Party Democratically Elected? – Mythbusting Berlin

The myth persists that Adolf Hitler rose to power through popular democratic choice. Yet history reveals a darker, more complicated truth. Hitler’s ascent involved exploiting democratic institutions, orchestrating violence, propaganda, and political intrigue—not a simple election victory. Understanding how Germany’s democracy collapsed into dictatorship helps illuminate the dangerous interplay between public desperation, elite miscalculations, and extremist ambition, providing crucial lessons for safeguarding democracy today.

Were The Allied Bombings Of Germany War Crimes? – Mythbusting Berlin

The history of the Allied bombing of Germany during the Second World War still triggers fierce debate. Was reducing cities to rubble a necessary evil – justice from above in a just war – or an unforgivable crime? Can the intentional targeting of civilians ever be justified as militarily necessary?

In a conflict where all rules seemed to vanish, an even more pertinent question persists: by the very standards they would use to judge their

Were The Nazi Medical Experiments Useful? – Mythbusting Berlin

Before the Nazi period, German medicine was considered the envy of the world – a shining monument to progress. But deep within that monument, a rot was spreading, one which would collapse the entire structure into an abattoir. From the wreckage, we are left with a profoundly uncomfortable inheritance: a moral enigma wrapped in doctor’s whites.

What to make of the data, the images, and the terrible knowledge gleaned from unimaginable human suffering. Whether

What Are The Origins Of The Nazi Salute? – Mythbusting Berlin

A specter is haunting the modern mind, a gesture so charged with the dark electricity of history that its mere depiction can unleash a storm of controversy.

It is a simple movement: the right arm, stiff and straight, raised to the sky. But in that simplicity lies a terrifying power, a symbol of a regime that plunged the world into an abyss and a chilling reminder of humanity’s capacity for organised hatred.

This

What Are The Origins Of The Nazi Swastika? – Mythbusting Berlin

Long before the legions of the Third Reich marched beneath its stark, unnerving geometry, the swastika lived a thousand different lives. It was a symbol of breathtaking antiquity, a globetrotting emblem of hope and good fortune that found a home in the most disparate of cultures. To even begin to understand its dark 20th-century incarnation, one must first journey back, not centuries, but millennia.

What Are The Pink Pipes In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

A first-time visitor to Berlin could be forgiven for thinking the city is in the midst of a bizarre art installation. Bright pink pipes, thick as an elephant’s leg, climb out of the ground, snake over pavements, arch across roads, and disappear back into the earth. Are they part of a complex gas network? A postmodern artistic statement? A whimsical navigation system? These theories, all logical, are all wrong. The truth is far more elemental,

What Do The Colours Of The German Flag Symbolise? – Mythbusting Berlin

What does a flag mean? Is it merely a coloured cloth, or does it hold the hopes, struggles, and identity of a nation? The German flag, with its bold stripes of black, red, and gold, is instantly recognisable. But the story of its colours is a tumultuous journey through revolution, suppression, and reinvention. The common explanation for their symbolism is a simple, romantic verse, yet the truth is a far more complex and contested tale,

What Happened To Adolf Hitler’s Alligator? – Mythbusting Berlin

It is often said that you can tell a lot about a person by their relationship with animals; that owners often come to look and behave like their pets. Or is it perhaps more that people choose their pets to correspond to their personality? Nazi leader Adolf Hitler’s love of dogs, for example, is well documented but what is there to make of his relationship with reptiles?

What Happenened To The German Royal Family? – Mythbusting Berlin

When the smoke cleared over the trenches in November 1918, the German Empire had evaporated, and with it, the divine right of the Hohenzollern dynasty. Conventional wisdom suggests the family simply vanished into the sepia-toned obscurity of history books—exiled, forgotten, and irrelevant. But dynasties, like weeds in a landscaped garden, are notoriously difficult to uproot entirely. The story of the German royals did not end with the Kaiser’s flight to Holland; it merely shifted gears.

What Is The Difference Between Fascism & Nazism? – Mythbusting Berlin

While the terms ‘Fascist’ and ‘Nazi’ are often bandied around interchangeably as shorthand for tyranny – Italian fascism and German National Socialism were distinctly different beasts. Albeit ideological kin. One an ideology of state-worship, born from post-war chaos and national pride; the other built upon a fanatical, pseudo-scientific obsession with race. Two peas in the same totalitarian pod – twins in tyranny – more succinctly summarised as the Nazi chicken to the Fascist egg.

What Was Checkpoint Charlie? – Mythbusting Berlin

Checkpoint Charlie remains among Berlin’s most visited historical sites, famed worldwide for its significance during the Cold War. Originally established as a modest border-crossing point, it evolved dramatically over the decades into an international symbol of freedom, espionage, and intrigue. Today, critics and locals often dismiss it as little more than a tourist trap—Berlin’s Disneyland—but how exactly did Checkpoint Charlie get its peculiar name, and what truths hide behind its popularity?

What Was Prussia? – Mythbusting Berlin

Prussia’s legacy is both remarkable and contentious—once a minor duchy, it rose dramatically to shape modern European history. Renowned for military discipline, administrative efficiency, and cultural sophistication, Prussia was instrumental in uniting the German states, laying foundations for a unified Germany. But how did this kingdom, with its roots in Baltic territories, achieve such prominence, and why does its complex history continue to evoke admiration, debate, and occasional discomfort in Germany today?

What Was The Berlin Airlift? – Mythbusting Berlin

In the ruins of 1948, the silence of Berlin was not a sign of peace, but a held breath before a new catastrophe. The city, drowning in rubble and political intrigue, became the staging ground for the twentieth century’s most audacious gamble. While popular history remembers the chocolate parachutes and smiling pilots, the reality of the Berlin Airlift was a terrifying operational nightmare born from a ruthless currency war. It wasn’t just a humanitarian mission;

What Was The Socialist Kiss? – Mythbusting Berlin

It is one of the most curious and enduring images of the Cold War: two middle-aged, grey-suited men, locked in a fervent embrace, their lips pressed together in a kiss of apparent revolutionary passion. This was the ‘Socialist Fraternal Kiss’, a ritual that, for a time, seemed to encapsulate the unwavering solidarity of the Eastern Bloc.

But what was behind this seemingly intimate gesture? Was it a genuine expression of camaraderie, a piece of

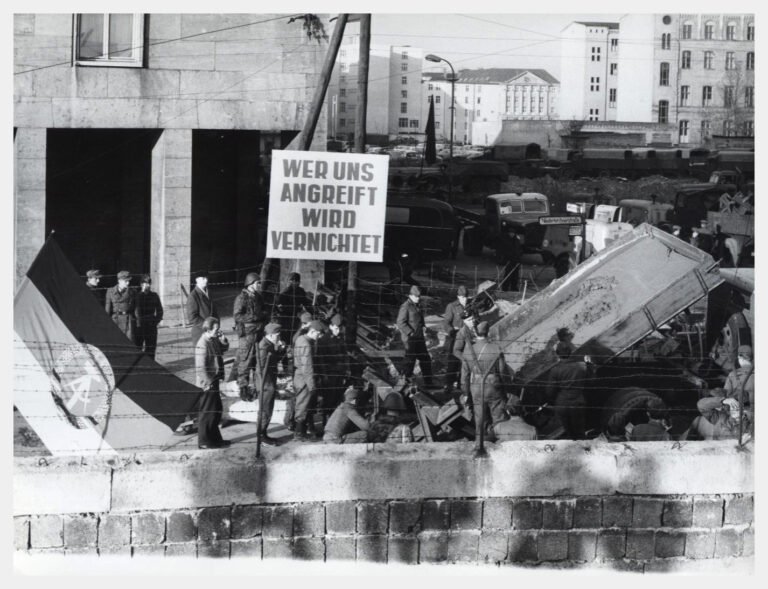

Who Built The Berlin Wall? – Mythbusting Berlin

One of the most common questions I have encountered from people curious about Berlin, and often so cryptically phrased. Who built the Berlin Wall? A simple five-word query, yet one that can be read one of two ways. More than thirty years since the ‘Fall of the Wall’, the story of its construction continues to baffle many who are mainly familiar with its existence through knowledge of its importance…

Who Really Raised The Soviet Flag On The Reichstag? – Mythbusting Berlin

One iconic photograph has come to symbolise the Red Army’s victory over Nazi Germany in 1945—the Soviet flag waving triumphantly above Berlin’s battered Reichstag building. Yet behind this enduring image lies controversy, confusion, and political manipulation. Who truly raised the Soviet banner atop the Reichstag? Was it a spontaneous act of heroism or carefully staged Soviet propaganda? Decades later, unraveling the truth reveals surprising layers beneath the mythologized symbol of Soviet triumph.

Who Was Really Responsible For The Reichstag Fire? – Mythbusting Berlin

Various theories have been posited as to who actually set fire to the German parliament in 1933. Was it the opening act in an attempted Communist coup or a calculated false flag operation carried out by elements of the Nazi Party, intended to create the conditions necessary for introducing single-party rule? And what part did the young man from Holland, arrested shirtless inside the building the night of the fire, play in this event?

Who Were The Last Nazis On Trial? – Mythbusting Berlin

More than eighty years after the Holocaust, courtrooms across Germany still echo with testimony from the final chapter of Nazi justice. Centenarian defendants in wheelchairs, their faces hidden behind folders, arrive to answer for crimes committed in their youth. These are not the architects of genocide—those men faced their reckoning at Nuremberg decades ago. These are the guards, the secretaries, the bookkeepers: ordinary people who enabled extraordinary evil. Their trials represent a legal revolution: the

Why Is Berlin The Capital Of Germany? – Mythbusting Berlin

There was little in its humble origins—as a twin trading outpost on a minor European river—to suggest that Berlin was destined for greatness. It sits on the flat expanse of the North European Plain, a landscape once dismissively referred to as the “sandbox of the Holy Roman Empire.” Unlike other world capitals, it lacks breathtaking scenery or a naturally defensible position. It is a city built not on majestic hills or a grand harbour, but