“It is the Jews who govern the stock exchange forces of the American Union. Every year makes them more and more the controlling masters of the producers in a nation of one hundred and twenty million; only a single great man, Ford, to their fury, still maintains full independence.”

Adolf Hitler, Mein Kampf (1935)

History, in its relentless pursuit of clarity, often simplifies the past into a series of easily digestible narratives.

We crave heroes and villains, clear-cut motives and unambiguous outcomes. Yet, the past is rarely so accommodating.

It is a messy, complicated, and often contradictory affair.

Take, for instance, the term “Nazi.”

Once a derogatory epithet for a member of the National Socialist German Workers’ Party, it has morphed into a generic term for a supporter of a defunct and universally reviled ideology.

The irony, of course, is that the Nazis themselves shied away from the term, preferring the more formal “National Socialist.” It was their enemies who weaponised the folksy, almost comical-sounding “Nazi” – then interpreted as a backwards farmer or peasant, or an awkward, clumsy yokel – as a term of derision.

Could one of the titans of 20th-century industry, a man whose name is synonymous with American ingenuity and the rise of the middle class, be counted among their number?

The question has lingered for decades: Was Henry Ford, the automotive pioneer who put the world on wheels, a Nazi?

The answer, like history itself, is not a simple yes or no.

It is a journey into the dark corners of a brilliant but deeply flawed mind, a story of populism twisted into prejudice, and a cautionary tale about the immense harm that can be wrought by a man of immense influence.

To understand the depths of Ford’s complicity, we must first understand the man himself.

–

The Man With The Motor Car

“The great need of the world has always been for leaders. With more leaders we could have more industry. More industry, more employment and comfort for all.”

Henry Ford, quoted in Barron’s (1931)

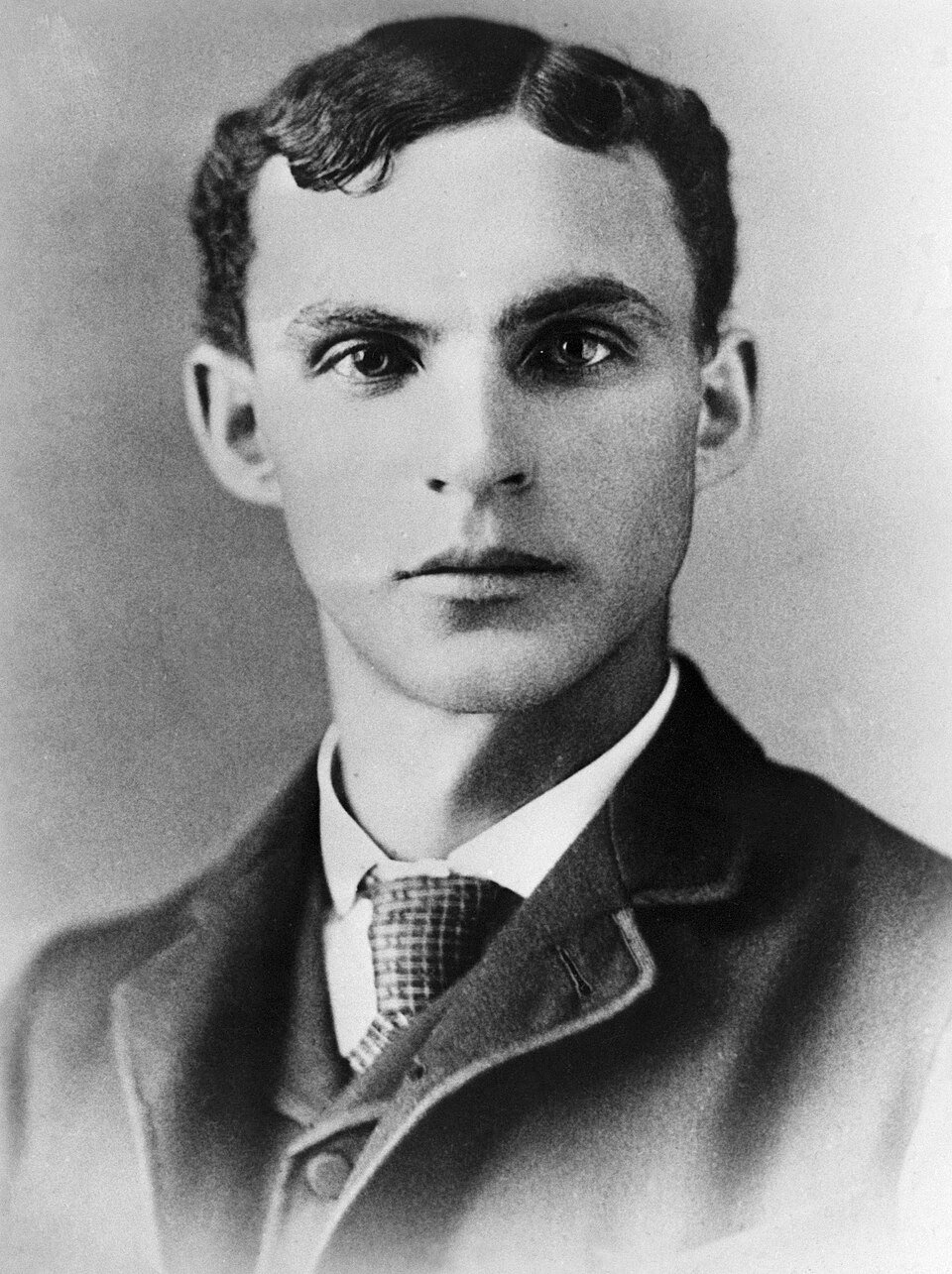

Born on a farm in Springwells Township, Michigan, in 1863, Henry Ford was a quintessential product of the American heartland.

From a young age, he displayed a remarkable aptitude for mechanics. A pocket watch gifted to him by his father at the age of 13 was promptly disassembled and reassembled, a feat that impressed friends and neighbors who soon brought him their own timepieces for repair. This innate curiosity and talent for tinkering would define his life’s work.

Unsatisfied with the drudgery of farm life, Ford left home at 16 to become a machinist’s apprentice in Detroit. He honed his skills, learning to operate and service steam engines, and even took up bookkeeping. After marrying Clara Ala Bryant in 1888 and the birth of their son, Edsel, in 1893, Ford’s ambition only grew.

While working as an engineer at the Detroit Edison Company, a position he rose to through his natural talents, he secretly worked on his own ‘horseless carriage’.

In a small shed behind his home, he built his first gasoline-powered buggy, the Quadricycle, in 1896. A meeting with Thomas Edison himself, who encouraged the young engineer’s automotive experiments, further fueled Ford’s determination.

After a few false starts and failed business ventures, Ford, along with a group of investors, founded the Ford Motor Company in 1903.

The rest, as they say, is history.

Ford’s introduction of the moving assembly line revolutionised industrial production, slashing the time it took to build a car from over 12 hours to a mere 2.5.

The result was the Model T, a car so affordable that it transformed the automobile from a luxury for the rich into a practical tool for the masses.

Ford became a folk hero, a symbol of American innovation and upward mobility. His decision to pay his workers a then-unheard-of five dollars a day was hailed as a stroke of genius, a way to create a loyal workforce and a new class of consumers who could afford the very products they were building.

Yet, beneath this veneer of benevolent capitalism lay a darker, more troubling ideology.

–

Politics, Race, & The Nazi Party

“If fans wish to know the trouble with American baseball they have it in three words—too much Jew.”

Henry Ford, 1920

Henry Ford was a man of contradictions.

A staunch pacifist who opposed America’s entry into the First World War, he was also a fervent anti-Semite who used his vast fortune and influence to spread a message of hate. This seemingly paradoxical combination of beliefs can be traced to his populist roots.

Ford, the self-made man from the heartland, harbored a lifelong suspicion of East Coast elites, international financiers, and Wall Street bankers. Groups he came to associate, in his increasingly paranoid worldview, with a global Jewish conspiracy.

His chosen mouthpiece for this virulent ideology was a small local newspaper, The Dearborn Independent, which he purchased in 1918. For the next seven years, the paper’s weekly circulation of nearly a million was used to relentlessly attack Jewish people. Every Ford dealership nationwide would carry the paper and distribute it to its customers.

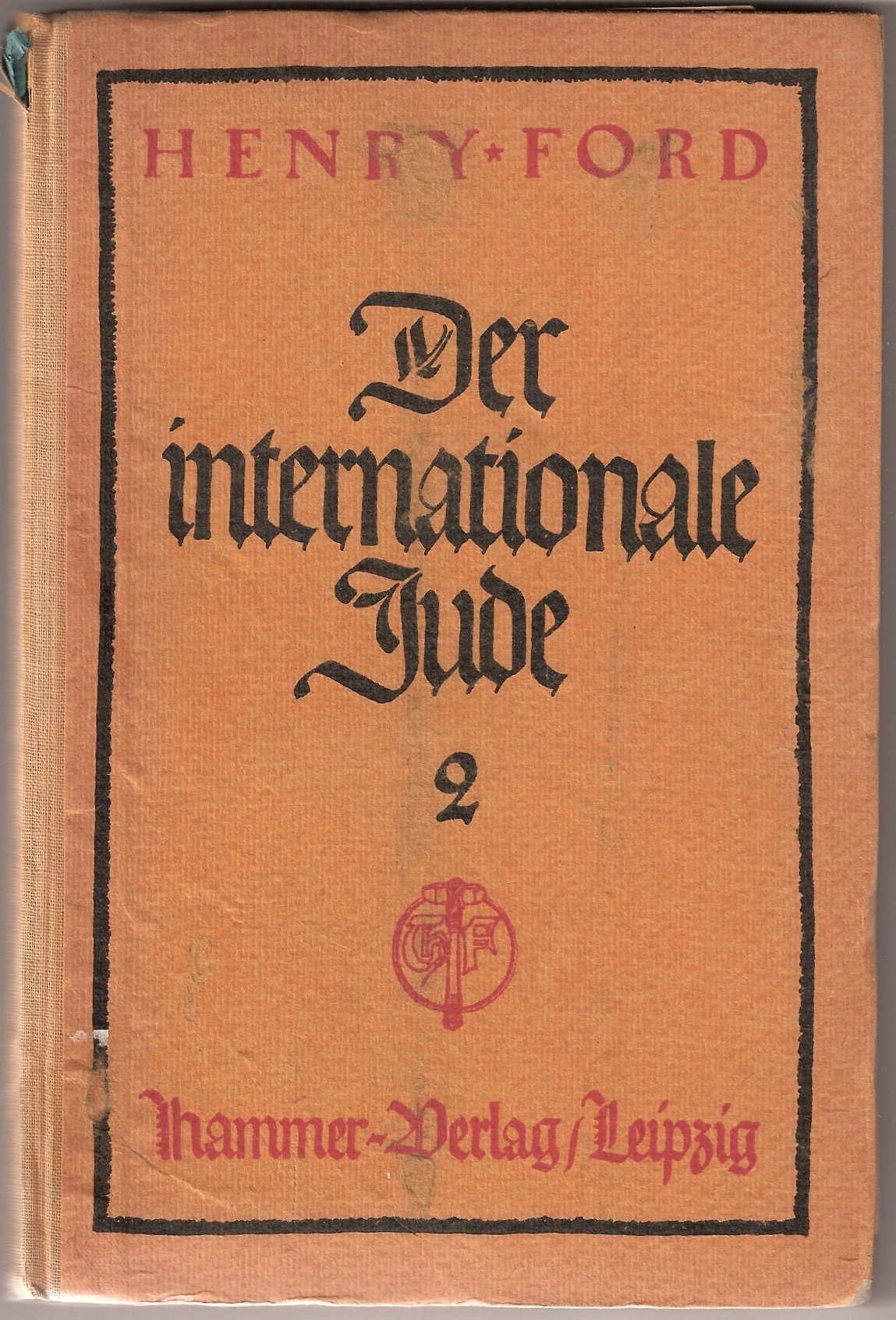

Under Ford’s direction, a series of ninety-one articles were published in 1920 under the banner of ‘The International Jew: The World’s Foremost Problem’.

These articles, soon compiled into a four-volume set of books, were a rambling and incoherent screed, a hodgepodge of anti-Semitic tropes and conspiracy theories. They accused Jews of instigating World War I, controlling the global financial system, conspiring to exploit American farmers, and corrupting American culture through Hollywood, bootleg liquor, and Jazz music.

The books were titled:

- The International Jew: The World’s Foremost Problems (vol. 1);

- Jewish Activities in the United States (vol. 2);

- Jewish Influences in American Life (vol. 3);

- and Aspects of Jewish Power in the United States (vol. 4)

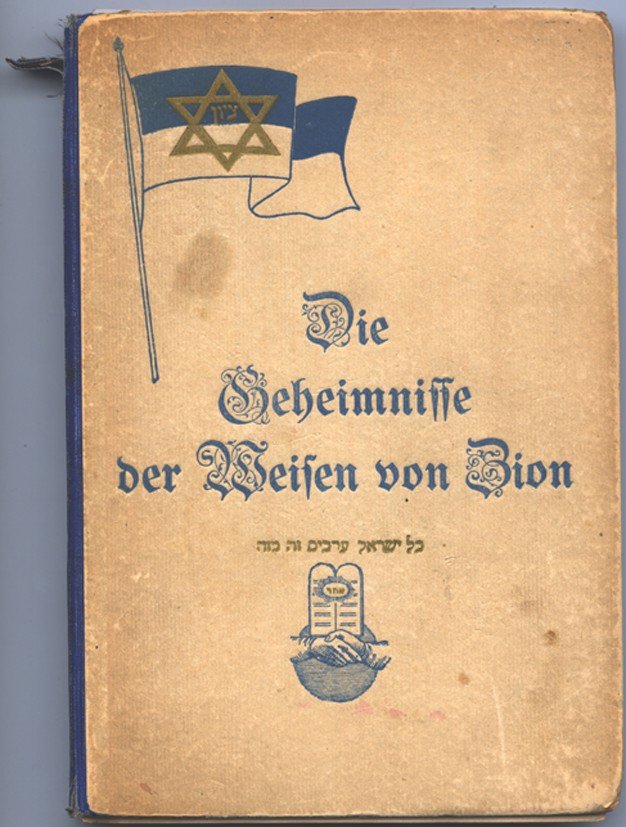

The primary source for much of the ‘evidence’ presented in ‘The International Jew’ was ‘The Protocols of the Elders of Zion’, a notorious and long-discredited forgery that purported to be the minutes of a secret meeting of Jewish leaders plotting to take over the world.

Ford’s newspaper gave this repugnant piece of propaganda a new lease on life, introducing it to a wide American audience and lending it a veneer of respectability.

More than a mere personal prejudice, Ford’s anti-Semitism was a core component of his political philosophy.

He believed that an international Jewish cabal was undermining the traditional, agrarian way of life that he so cherished. His attacks on Jews were, in his warped view, a defense of the common man against the corrupting influence of global elites.

This populist-fueled anti-Semitism found a receptive audience in a post-war America grappling with social and economic upheaval – and spread like a bacillus back across the Atlantic. Finding a receptive audience amidst the economic and political turmoil of 1920s Germany.

Translated into German in 1922, ‘The International Jew’ was openly cited as an influence by members of the rising National Socialist movement – becoming a key text in the country’s burgeoning right-wing nationalist scene. The book would be published by Theodor Fritsch, founder of several antisemitic parties and a member of the Reichstag, Fritsch heavily involved in influencing German anti-Semitic discourse.

Baldur von Schirach, Reich Youth Leader of the Nazi Party and Gauleiter of Vienna, when testifying at the Nuremberg Trials in 1945 would state: “I read it and became anti-Semitic. In those days this book made such a deep impression on my friends and myself because we saw in Henry Ford the representative of success, also the exponent of a progressive social policy. In the poverty-stricken and wretched Germany of the time, youth looked toward America, and apart from the great benefactor, Herbert Hoover, it was Henry Ford who to us represented America.”

Despite the closure of the Dearborn Independent in 1927, after a successful libel lawsuit by one of its Jewish targets, copies of the defunct paper would continue to circulate around the world well after the United States entered the war against Germany in 1941.

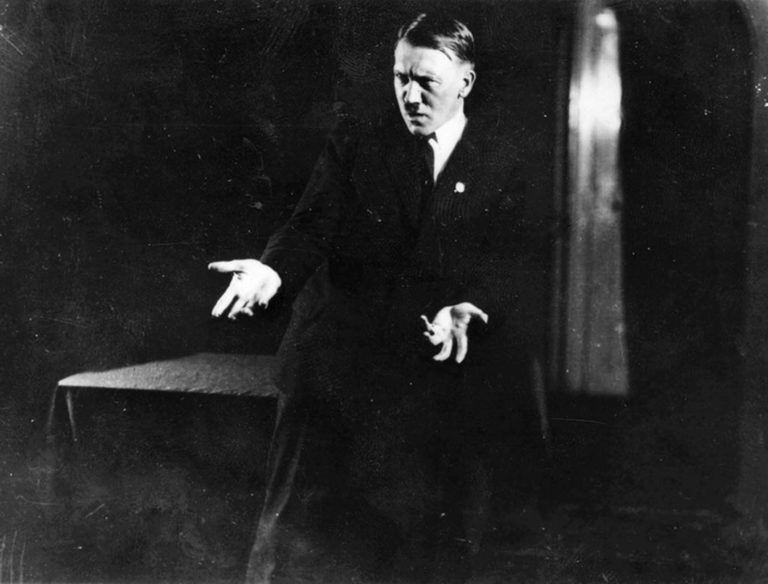

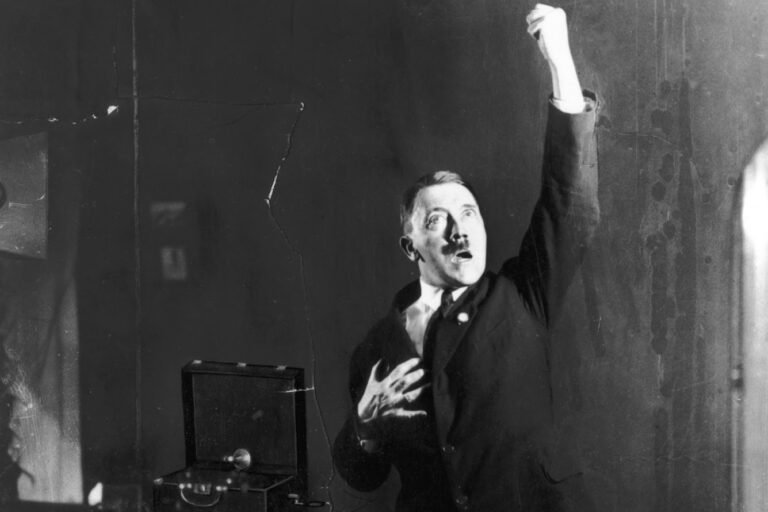

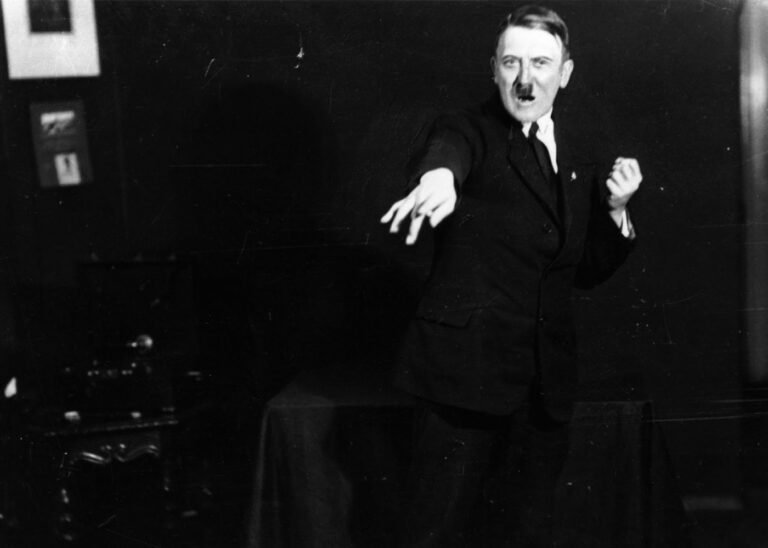

Adolf Hitler, in his own manifesto, Mein Kampf, praised Ford as “the only great man” in America who had resisted Jewish influence. Hitler saw in Ford a kindred spirit, a fellow populist who understood the supposed threat posed by international Jewry.

Like Hitler, Ford was also an early opponent of the consumption of tobacco, having published an anti-smoking book, circulated to youth in 1914, called The Case Against the Little White Slaver, which documented many dangers of cigarette smoking attested to by many researchers and luminaries. At the time, smoking was ubiquitous and not yet widely associated with health problems, making Ford and Hitler’s opposition to cigarettes particularly remarkable.

A life-size portrait of Henry Ford hung in Hitler’s Munich office, and he told a Detroit News reporter in 1931 that he regarded the American industrialist as his “inspiration”.

The admiration was mutual. In 1938, on his 75th birthday, Henry Ford was awarded the Grand Cross of the German Eagle, the highest honor the Nazi regime could bestow on a foreigner. Ford proudly accepted the award, a clear symbol of his ideological affinity with the Third Reich.

While Ford never officially joined the Nazi party, his financial and ideological support for the movement is undeniable.

A staunch opponent of the United States entering the Second World War, Ford claimed that the torpedoing of U.S. merchant ships by German submarines was the result of conspiratorial activities undertaken by war-financier makers. When Rolls Royce was searching for a manufacturer in the United States to make Merlin engines (for the Spitfires and Hurricanes that were then defending Great Britain against the Nazi onslaught), Ford at first agreed, then reneged. Although he would eventually join the war effort on the US side, after the declaration of war in 1941, and establish the largest assembly line in the world at the time – at Willow Run near Michigan – to build B-24 Liberators.

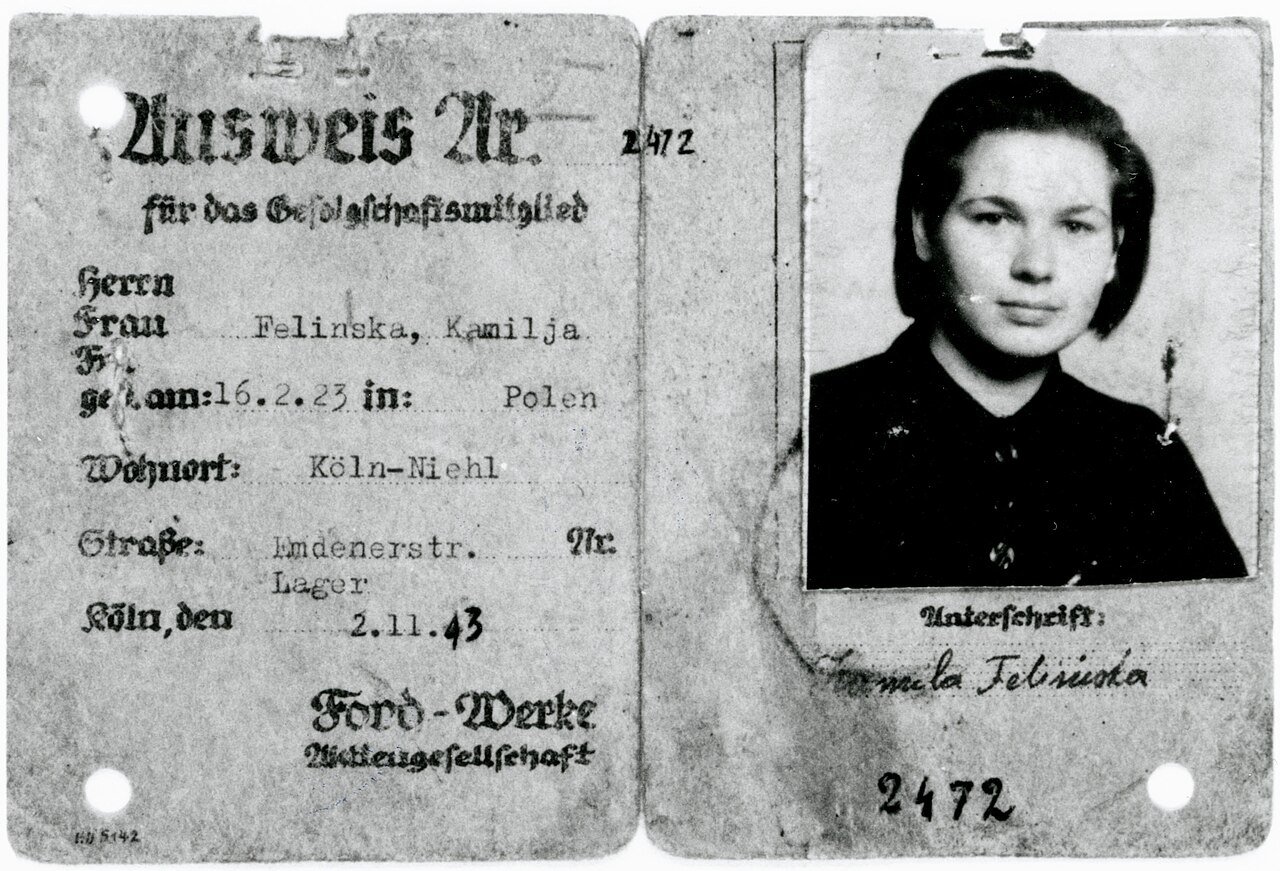

The Ford-Werke AG, established in Germany in 1924, continued to function throughout the Nazi period, however, manufacturing the turbines used in the V-2 rockets – alongside production of Köln, Rheinland, Eifel, and later Taunus automobiles. In-fact, Ford’s River Rouge plant would serve as the model for the production of the ‘People’s Car’ in Nazi Germany – the Volkswagen.

Allied airmen bombing the German city of Cologne, where the Ford-Werke plant was located, were advised to avoid bombing the location. In-fact, cars manufactured in Cologne didn’t bear the famous Ford logo on the hood, but Cologne Cathedral.

Despite the special precautions taken against the Cologne plant, the company was awarded over $1m after the war in compensation for damage caused.

The full extent of Ford’s financial support for the Nazi party remains a matter of historical debate.

While there is no definitive proof of direct donations, his company’s German subsidiary, Ford-Werke, actively collaborated with the Nazi regime, using forced labor from concentration camps to produce vehicles for the German war effort and undertaking the illegal manufacture of munitions.

At the height of the Second World War, Ford-Werke stopped making customer cars and instead used all materials—iron, plate glass, leather, rubber—for war production.

A 1945 U.S. Army report damningly referred to Ford-Werke as “an arsenal of Nazism”.

Some defence can be proposed in that the company fell under the direct control of the Nazi government during the years of its utilisation of slave labour and contribution to the Nazi war effort. At the time, Henry Ford had no influence at Ford Werke.

What is known is that on February 1st, 1924, during the ‘years of exile’ for the Nazi Party after Hitler’s attempted Bavarian coup in 1923, Ford received Kurt Ludecke, a representative of Hitler, at his home. Ludecke was introduced to Ford by Siegfried Wagner (son of the composer Richard Wagner) and his wife Winifred, both Nazi sympathizers and anti-Semites. Ludecke asked Ford for a contribution to the Nazi cause, but was apparently refused.

Despite this. that same year, Heinrich Himmler, boasted Ford as “one of our most valuable, important, and witty fighters”.

Ford certainly did, however, give considerable sums of money to Boris Brasol, in his capacity as a member of the Aufbau Vereinigung, an organisation linking German Nazis and White Russian emigrants, which financed the recently established Nazi Party.

In supporting the Aufbau Vereinigung, this move put Ford in the same league as other prominent members of the organisation, such as: Alfred Ernst Rosenberg, one of the key ideologues behind the National Socialist movement and author of the pseudo-scientific racial work, The Myth of the Twentieth Century (1930); Max Amann, the first Nazi business manager and later editor of the Nazi publishing house, Eher Verlag; and German General, Erich Ludendorff, key figure in Adolf Hitler’s 1923 Beer Hall Putsch.

The final coda to claims that Ford was indeed on the wrong side of history come from reports of his death, which occurred in 1947 as he had reached the age of 83. According to author, Robert Lacey, writing in ‘Ford: The Men and the Machines’ – a close associate of Ford reported that when he was shown newsreel footage of the Nazi concentration camps, he “was confronted with the atrocities which finally and unanswerably laid bare the bestiality of the prejudice to which he contributed.”

Collapsing with a stroke – his last and most serious – he would succumb to a cerebral hemorrhage soon after.

The Persil Test

“Leaving aside the probability that he (Hitler) was informed of their content or at least their import, through conversations with his friends… the vehicle seems to have been a series of newspaper articles ghost-written for the American motor manufacturer Henry Ford and published in 1920 in a collected, bound edition, under the title ‘The International Jew: The World’s Foremost Problem’. A copy was included in Hitler’s library.”

Richard J. Evans discussing Hitler’s exposure to the ‘Protocols of the Elders of Zion’ – The Hitler Conspiracies (2020)

In the immediate aftermath of the Second World War, the Allied powers undertook a massive effort to purge German society of Nazi influence. This process, known as ‘denazification’, involved everything from prosecuting war criminals to removing former Nazi party members from positions of power.

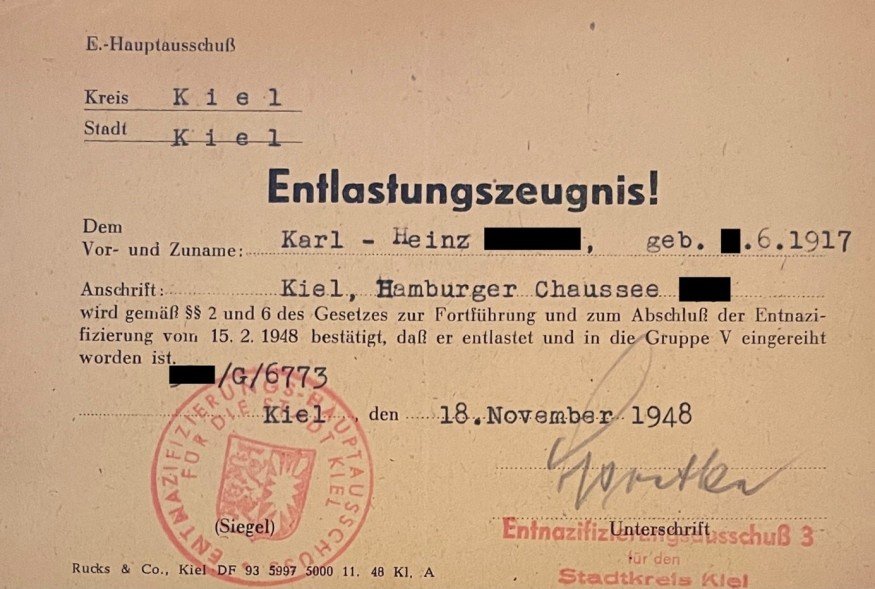

For those seeking to clear their names in the western part of the country, a key document was the so-called Persilschein, or ‘Persil certificate’.

Named after a popular brand of laundry detergent, the Persilschein was a testament to an individual’s ‘whitewashed’ past, a certificate that absolved them of any Nazi taint. This often involved procuring affidavits from friends, neighbors, or even former enemies, attesting to the individual’s good character and anti-Nazi credentials.

The Persilschein quickly became a symbol of the moral compromises and ethical ambiguities of the post-war era.

It was a recognition that, for many Germans, the lines between guilt and innocence, complicity and resistance, were often blurred.

The specifics of this certificate of exoneration were that on September 26th 1945, Law No. 8 of the American military government stipulated that in the American zone, members of the Nazi Party could, from that point on, only be permitted to work in ‘ordinary jobs’ in the economy, i.e., jobs without managerial responsibilities.

This law, however, provided for an appeal procedure in which those affected could attempt to credibly demonstrate, using ‘facts’, that they had been National Socialists “only in name” and had not been “actively” involved in its aims.

For ordinary Germans, denazification often meant appearing before a tribunal and being classified into one of five categories, from ‘major offender’ to ‘exonerated’.

“Major Offender: Hauptschuldige

Offender (Activist, Militarist, or Profiteer): Belastete

Lesser Offender: Minderbelastete

Follower: Mitläufer

Exonerated Person: Entlastete”

Those deemed part of the first two categories faced up to five years of hard labor, had to surrender some or all of their assets as restitution, were barred from holding public office, and lost their entitlement to a state pension or retirement benefits.

Those deemed less incriminated also faced professional restrictions and salary reductions. So-called ‘Mitläufer’ (followers) could be expected to pay a small fine, while those fully exonerated went unpunished.

What if we – as a kind of devil’s advocate – were to apply this ‘Persil Test’ to Henry Ford? If we were to posthumously evaluate his life and actions, what would the verdict be?

On the one hand, Ford’s defenders could point to his pacifism, his opposition to America’s entry into World War I, and his pioneering labor practices. They might argue that his anti-Semitism, while regrettable, was a product of his time, a reflection of the widespread prejudice that existed in early 20th-century America. They might even claim that his acceptance of the Grand Cross of the German Eagle was a naive misstep, a failure to fully grasp the true nature of the Nazi regime.

But the evidence against Ford is overwhelming.

His anti-Semitism was not a passive prejudice; it was an active and all-consuming obsession. He used his immense wealth and power to disseminate a message of hate that poisoned the well of public discourse and gave aid and comfort to the most murderous regime in human history.

His newspaper, ‘The Dearborn Independent’, and his book, ‘The International Jew’, were not simply expressions of personal opinion; they were weapons in a campaign of vilification and dehumanisation that would have devastating consequences.

The influence of Ford’s writings on the Nazi movement is undeniable.

Hitler and other leading Nazis saw in Ford a powerful ally, a confirmation that their own twisted ideology had supporters in the heart of America. The Grand Cross of the German Eagle was not a mere trinket; it was a symbol of a shared worldview, a recognition of Ford’s contribution to the cause of international anti-Semitism.

Even his much-vaunted apology, issued in 1927 after a lawsuit forced his hand, rings hollow.

While he publicly retracted his anti-Semitic statements and closed ‘The Dearborn Independent’, he continued to harbor his prejudices in private. And his company’s collaboration with the Nazi regime during the war years speaks volumes about the depth of his complicity.

At the end of the Second World War, those in Germany who – like Ford – had provided the intellectual and moral poison for the Third Reich were called to account.

Alfred Rosenberg, the shoddy philosopher and racial theorist who served as the movement’s intellectual architect, found his abstract hatreds translated into a concrete sentence. He was hanged at Nuremberg.

More telling, however, was the fate of a man whose role perfectly mirrored Ford’s own publishing venture. Julius Streicher, the proprietor of the vile propaganda sheet Der Stürmer—a publication that rivalled The Dearborn Independent in its crude, pornographic obsession with anti-Semitism—was also sent to the gallows. The Nuremberg tribunal made a momentous decision in his case: that the relentless incitement to persecution and murder through mass media was itself a crime against humanity. Streicher did not command armies or gas chambers, but his words had helped create the environment where such atrocity flourished.

The engineers and financiers of the Reich, meanwhile, faced their own reckoning, though often with more ambiguous results.

Alfried Krupp, head of the industrial behemoth that armed Hitler’s legions, was convicted for the systematic use of slave labour—a charge for which Ford’s own German operations were unequivocally guilty—and sentenced to twelve years, though he was pardoned after only three.

The Bechstein family, who had used their piano fortune to become some of Hitler’s earliest and most intimate patrons, had their company seized.

Ferdinand Porsche, Hitler’s favourite automotive engineer, was imprisoned by the French for his complicity.

One is forced to wonder: had Henry Ford been a German citizen on the losing side of the conflict, what dock would he have found himself in?

He was an ideologue like Rosenberg, a propagandist like Streicher, and an industrialist like Krupp. It seems only an accident of geography and his winning-team passport saved him from facing the very justice his German counterparts received.

In the final analysis, there should be no Persilschein for Henry Ford.

No amount of historical whitewashing can cleanse the stain of his anti-Semitism. He was a man of great genius and great hatred, a pioneer who pushed humanity forward with one hand and dragged it back into the dark ages with the other.

–

Conclusion

So, was Henry Ford a Nazi?

If we define a Nazi as a card-carrying member of the National Socialist German Workers’ Party, then the answer is no. But if we define it as someone who subscribed to and actively promoted the core tenets of Nazi ideology – racial hatred, conspiracy theories, and a belief in the superiority of one group over another – then the answer is an unequivocal yes.

To ignore the dark side of Henry Ford’s legacy is to do a disservice to history and to the victims of the ideology he so enthusiastically embraced.

He may have put the world on wheels, but he also helped pave the road to Auschwitz.

And for that, he must be judged accordingly.

***

If you’ve enjoyed reading this article, consider booking one of our private guided tours of Berlin.

HISTORICAL ARTICLES

Mythbusting Berlin

Are There Any Nazi Statues Left In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

Visitors to Berlin often arrive expecting to find the physical remnants of the tyranny of the 20th century still standing – statues of dictators, triumphal arches, or bronze idols. Instead, they often find none. The stone symbols and statues of the Third Reich are still gazing down on them, however, hiding in plain sight. But why are there no statues of Hitler? Did the Allies destroy them all in 1945, or is the truth stranger

Could The Western Allies Have Captured Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

To contemplate a Western Allied capture of Berlin in 1945 is to challenge the established endgame of the Second World War. What was the true military and logistical feasibility of a Western Allied assault on the Nazi capital? What factors truly sealed Berlin’s fate, and what might have changed had the Allies pushed eastward?

Answering these questions means delving into the complex interplay of logistics, political maneuvering, and the competing visions for a post-war world

Did Any Of The Rothschild Dynasty Die In The Holocaust? – Mythbusting Berlin

The Rothschild name is synonymous with immense wealth, influence, and persistent conspiracy theories—especially during the era of Nazi Germany. Often targeted by antisemitic propaganda, the family’s survival during World War II has sparked myths about their supposed immunity from Nazi persecution. But did any Rothschild family member actually perish in the Holocaust? This article explores that compelling question, unraveling historical misconceptions and revealing the reality behind one of Europe’s most famous dynasties.

Did Frederick The Great Introduce The Potato To Germany? – Mythbusting Berlin

One of the more bizarre claims to fame attributed to the first King of Prussia is that the man who would go down in history known as Frederick the Great introduced the potato to Germany during his reign back in the 1700s. This starchy root vegetable has undoubtedly become a staple part of German cuisine – an essential addition to any plate of Schnitzel, Schweinshaxn, and Königsberger Klopse – however, whether Frederick the Great is

Did Hitler Escape To Argentina In 1945? – Mythbusting Berlin

Although Nazi leader, Adolf Hitler, certainly remains an inescapable figure, could there be any truth to the story of his escape to Argentina in 1945? That the most wanted man on earth could simply vanish, to spend the rest of his life peacefully in South American obscurity captivates imaginations. Yet, despite numerous investigations, this tale persists primarily as myth—fueled by speculation, hearsay, and conspiracy theories.

Did Hugo Boss Design The Nazi Uniforms? – Mythbusting Berlin

The idea that Hugo Boss – the man whose name now adorns expensive suits and fragrances – was the creative genius behind the Nazi uniforms suggests a terrifying collision of haute couture and holocaust – a marriage of high style and high crimes. The image is striking: a German tailor sketching the ultimate villain’s costume. But history, as usual, is far messier, more bureaucratic, and more banal than the internet memes suggest. To understand who

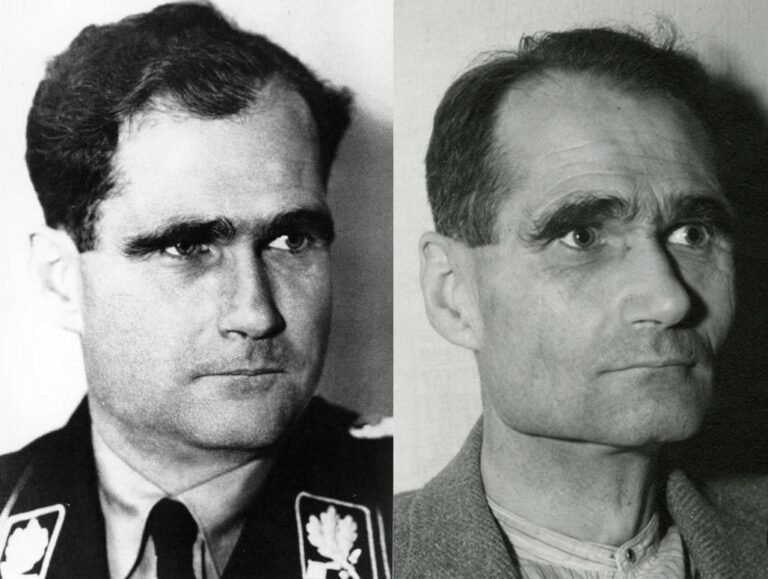

Did Rudolf Hess Really Commit Suicide? – Mythbusting Berlin

On a summer’s day in 1987, the last Nazi war criminal of the Nuremberg trials was found dead in a prison built for hundreds, yet for two decades, housed only him. The official verdict was suicide, a straightforward end to a life defined by fanaticism, delusion, and contradiction.

But the simplicity of the report belied the complexity of the man and the 46 years he had spent in Allied custody. In the meticulously controlled

Did The Nazis Develop Nuclear Weapons? – Mythbusting Berlin

The Nazi obsession with super-weapons became so serious in the closing stages of the Second World that Adolf Hitler personally believed that such ‘Wunderwaffen’ both existed in a usable form – and would save the country from defeat. Had the Nazis managed to develop nuclear weapons by 1945 – the outcome of the war would surely have been different. But how close were Hitler, Himmler, and his henchmen to developing an A-bomb?

Did The Nazis Invent Decaf Coffee? – Mythbusting Berlin

Persistent rumors claim that Nazis preferred their coffee anything but pure, leading some to wonder if they might have influenced the development of decaffeinated coffee. Although decaf was already widely available across Europe by the mid-20th century, speculation continues: could the Nazis really have played a role in popularizing—or even discovering—this caffeine-free alternative, or is this simply another caffeinated conspiracy cooked up to sensationalize an ordinary historical detail?

Did The Nazis Invent The Bicycle Reflector? – Mythbusting Berlin

The fruits of wartime ingenuity are plenty – so many, in-fact, that it has become somewhat of a worn cliche that as the guns start firing the innovators get to work, often solving problems while providing more problems for the enemy to overcome.The kind of progress that results in the production of newer improved, more lethal weapons, such as to increase the chances of victory.

Did The Nazis Run The Largest Counterfeiting Operation In History? – Mythbusting Berlin

During the Second World War the Nazis masterminded an astonishing plot to destabilise Britain by flooding its economy with counterfeit banknotes. Crafted in secret by concentration camp prisoners, this forged fortune became the most ambitious counterfeiting operation ever attempted. But was it history’s largest? Dive into the extraordinary tale of Operation Bernhard,

rife with deception, survival, and intrigue—revealing the truth behind one of the Third Reich’s most audacious schemes and its surprising legacy.

Did The Second World War End In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

When is a war ever truly over? When the last shot is fired in anger would seem like the best measure. Rarely, though, is it possible to gain insight into such a moment.

Remarkably, a record still exists of such a moment at the end of the First World War on the Western Front. A seismic register and recording of the last belching battery of British guns firing artillery across no-man’s-land, followed by a profound

Did The Spanish Flu Pandemic Help The Nazis Take Power? – Mythbusting Berlin

The devastating Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918-1919 struck amid Germany’s post-war turmoil, compounding social instability, economic hardship, and widespread political disillusionment. Could this catastrophic health crisis have indirectly paved the way for Nazi ascension? While often overshadowed by war and revolution, the pandemic’s profound psychological and societal impacts arguably contributed to the perfect storm, enabling extremist ideologies—including Nazism—to gain popularity and ultimately seize power in a fractured Germany.

Have Adolf Hitler’s Remains Been DNA Tested? – Mythbusting Berlin

In the smouldering ruins of Berlin in 1945, the world’s most wanted man vanished. Did Adolf Hitler, as official history attests, die by his own hand in the Führerbunker? Or did he escape, fuelling a thousand conspiracy theories that have echoed for decades? For years, the Soviets claimed to hold the gruesome proof of his death: a skull fragment and a set of teeth, locked away in Moscow archives. But in an age of definitive

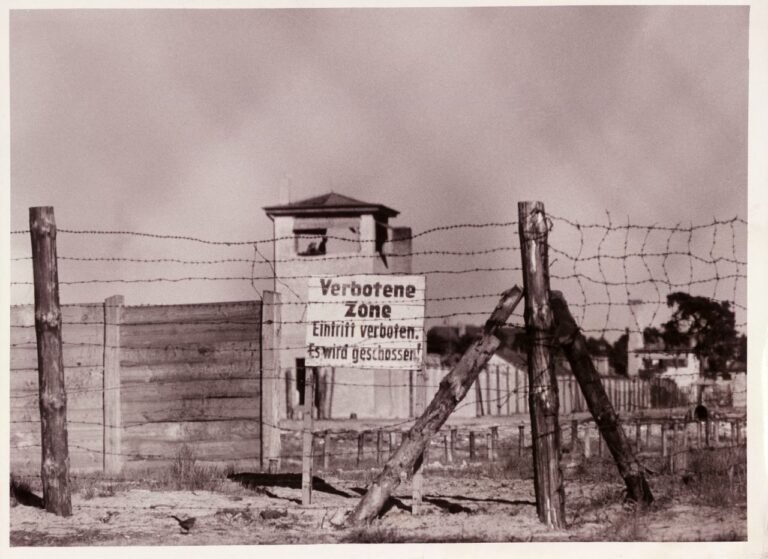

How Did The Nazi Concentration Camps Differ From The Soviet GULAG?

The Nazi concentration camps and Soviet Gulag system have often been conflated in popular imagination—twin symbols of twentieth-century totalitarian horror. Yet the two systems operated on fundamentally different principles. One extracted labor to fuel industrialisation while accepting mass death as collateral damage; the other evolved into purpose-built machinery of genocide. Understanding these distinctions isn’t merely academic—it reveals how different ideologies produce different atrocities, and why Germany and Russia reckon with these legacies so differently today.

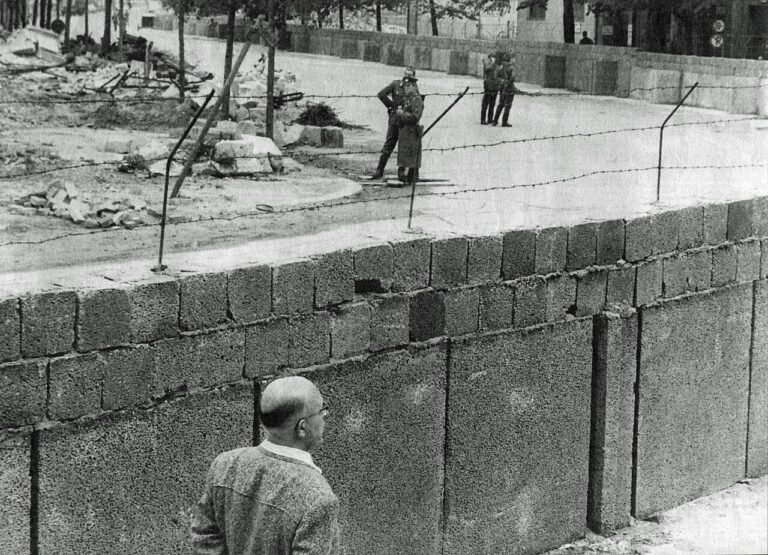

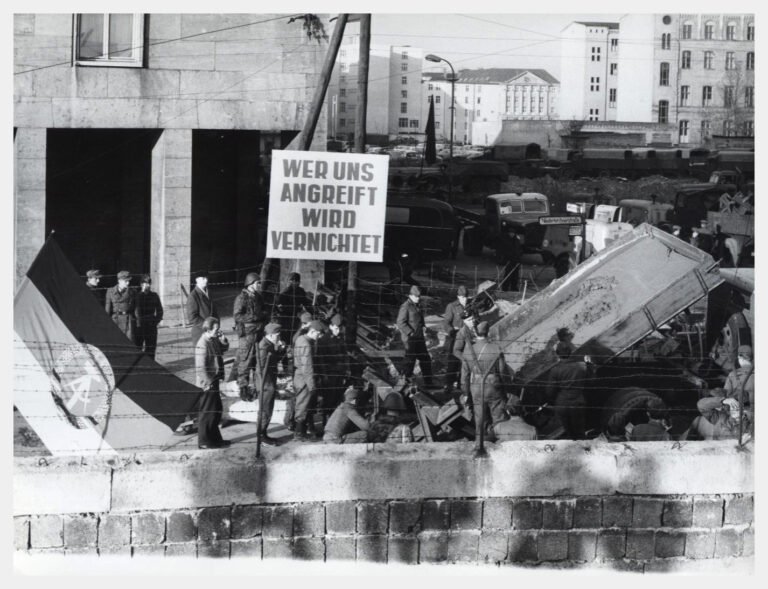

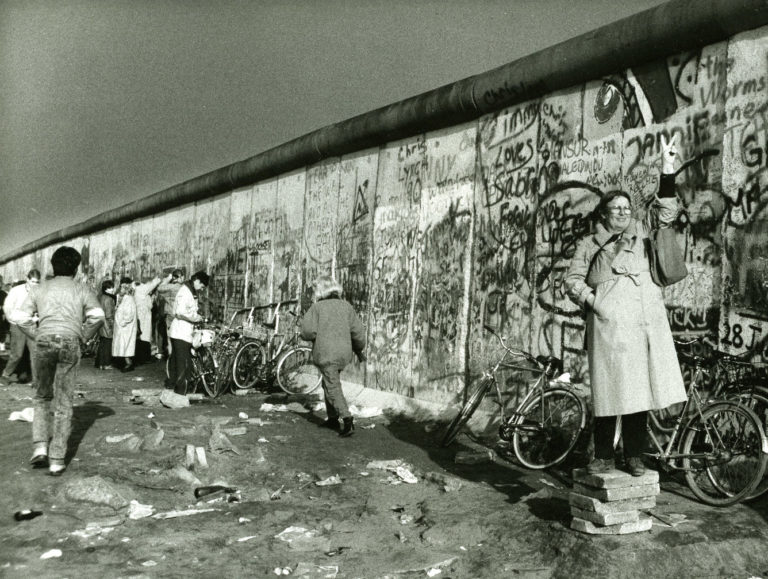

How Long Did It Take To Build The Berlin Wall? – Mythbusting Berlin

It is one of the most enduring images of the 20th century: a city divided overnight. The popular narrative tells us that Berliners went to sleep in a unified city and woke up in a prison. While the shock of August 13th 1961, was very real, the idea that the ‘Wall’ appeared instantly is a historical illusion. The physical scar that bisected Berlin was not a static creation, but a living, malevolent beast that evolved

How Many Assassination Attempts On Adolf Hitler Were There? – Mythbusting Berlin

Nazi leader, Adolf Hitler, projected an aura of invincibility, a man of destiny shielded by providence. But behind the carefully constructed image of the untouchable Führer lies a story of constant threat, of bombs that failed to detonate, and errant bullets that missed their mark. Unearth the hidden history of the numerous attempts on Hitler’s life as we explore the courage of those who tried to change the course of history and the devil’s luck

How Many Jews Died In The Holocaust? – Mythbusting Berlin

The answer to the question posed of how many Jews died in the Holocaust is a simple one: too many. That merely one death was an unforgivable obscenity is a fundamental and necessary realisation in understanding the capriciousness of this unparalleled racial genocide. To comprehend, however, the full number of Jews murdered in Europe by the Nazi regime in the 1930s and 1940s is a detective story of epic proportions: the evidence overwhelming, multifaceted, and

How Many People Died Trying To Escape East Germany? – Mythbusting Berlin

The image of the Berlin Wall is seared into our collective memory, a concrete symbol of Cold War oppression. We think of the daring escapes and the tragic deaths of those who failed. But that well-known number is only a fraction of the truth. The story of those who died trying to escape East Germany is far broader and more complex than most imagine, stretching along a thousand-kilometer border and out into the cold waters

How Old Is Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

A relatively new arrival in Europe, Berlin is over 1000 years younger than London, nevermind Rome or Athens, Jerusalem or Jericho. Just how old is Berlin though?

A question fraught with false assumptions and distortions – that has more often than not been answered with propaganda as it has with the cold hard truth.

Was Adolf Hitler A Drug Addict? – Mythbusting Berlin

Solving the enigma of the ‘Führer’ has become a preoccupation for many, since the arrival of the Austrian-German onto the world stage – although moving beyond the mythology without falling into the trap of prejudically extrapolating on the psychopathography of Hitler or demonising so as to excuse his actions has proven problematic. What to make of the man who became more than the sum of his masks? The painter; the military dilettante, the mass murderer,

Was Adolf Hitler A Freemason? – Mythbusting Berlin

History abhors a vacuum, but adores a mystery. Such is the speculative fiction suggesting a secret allegiance behind the rise of the Third Reich – that the catastrophe of the Second World War was orchestrated from the shadows of a Masonic lodge. The image of Adolf Hitler—the drifter from Vienna turned dictator—as a covert initiate of the very brotherhood he publicly reviled, however, creates a paradox that collapses under scrutiny. As when we unlock the

Was Adolf Hitler Gay? – Mythbusting Berlin

In the shadowy corridors of Third Reich history, few questions provoke as much tabloid curiosity and scholarly exasperation as the sexuality of Adolf Hitler. For decades, rumors have swirled—whispered by political enemies in 1930s Munich, psychoanalyzed by American spies in the 1940s, and sensationalized by revisionist authors today. Was the dictator who condemned thousands of men to concentration camps for “deviant” behavior hiding a secret of his own? By peeling back the layers of propaganda,

Was Adolf Hitler Jewish? – Mythbusting Berlin

Was the dictator who orchestrated the murder of millions of European Jews secretly one of them? It is perhaps the darkest irony imaginable, a story whispered for decades in backrooms, bars, and conspiracy forums alike. The most-common rumour – the ‘Frankenberger Myth’ – suggests that Adolf Hitler’s paternal grandfather was Jewish, a secret so damaging it could have unraveled the entire Nazi regime. But where does this claim come from? And, more importantly, is there

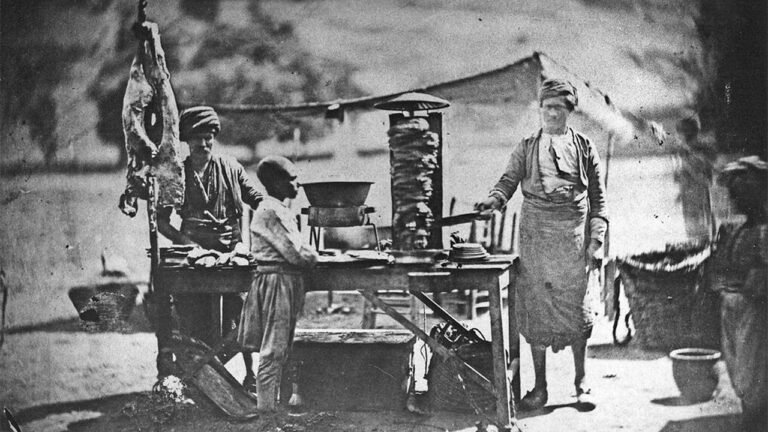

Was Currywurst Invented In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

Explore the story behind what many consider Berlin’s most iconic snack—the ever-so-humble Currywurst. Often hailed as an enduring symbol of culinary creativity amid Cold War scarcity, this humble dish has inspired fierce debate about its true origin. But was it genuinely invented here in Berlin, or have proud locals simply adopted and elevated this spicy street-food favorite into legendary status all their own?

Was Fanta Invented By The Nazis? – Mythbusting Berlin

As one of the most secretive organisations in the world, the Coca Cola corporation refuses to share its secret recipe with anyone. Famously insisting only on shipping the base syrup of its drinks to plants around the world to be carbonated and distributed.

This combined with the trade limitations of the Second World War may have led to the introduction of one of the most popular soft-drinks in the world. But could it be true:

Was Frederick The Great Gay? – Mythbusting Berlin

Frederick II of Prussia, better known as Frederick the Great, is often remembered as the archetypal enlightened monarch – a brilliant military commander, patron of the arts, and learned philosopher. Yet behind the stern portraits of this 18th-century warrior-king lies a personal life long shrouded in intrigue and speculation. Intrigue around the king’s sexual orientation has persisted through the centuries, chiefly revolving around one question: Was Frederick the Great gay?

Was Henry Ford A Nazi? – Mythbusting Berlin

US auto tycoon, Henry Ford, holds the ignominious distinction of being the only American Adolf Hitler praised by name in his National Socialist manifesto: ‘Mein Kampf’. This was not, as it turns out, the only connection between Ford and the Party of Hitler, Himmler, and the Holocaust.

Ford’s overt affinity with the Third Reich reveals a troubling past. How deep these connections ran, and how consequential they were for both sides, is a chapter

Was The Colour Blue Invented In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

Tracing the true history of blue—from ancient Egyptian dyes to the accidental discovery of Prussian Blue in a Berlin lab. We’ll debunk myths about seeing blue, explore colonial indigo plantations, scale mountains with a cyanometer, and trace Van Gogh’s starry skies—all to answer one question: how did Berlin shape our understanding of the world’s rarest color?

Was The Döner Kebab Invented In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

Unlikely icon of immigrant success; fast food symbol of the working class; over-hyped midnight disco eat; or culturally appropriated cuisine? Its influence goes far beyond layers of seasoned meat and fresh vegetables stuffed into pita bread. But does Berlin deserve credit as the Döner Kebab’s true birthplace, or has the city merely refined and popularized a culinary tradition imported from elsewhere?

Was The Fall Of The Berlin Wall An Accident? – Mythbusting Berlin

On a seasonally crisp night in November 1989, one of the most astonishing events of the 20th century occurred. After twenty eight years, three months, and twenty eight days of defining and dividing the German capital, the Berlin Wall ceased to exist – at least in an abstract sense. Although the removal of this symbol of the failure of the East German system would take some time, its purpose – as a border fortification erected

Was The Nazi Party Democratically Elected? – Mythbusting Berlin

The myth persists that Adolf Hitler rose to power through popular democratic choice. Yet history reveals a darker, more complicated truth. Hitler’s ascent involved exploiting democratic institutions, orchestrating violence, propaganda, and political intrigue—not a simple election victory. Understanding how Germany’s democracy collapsed into dictatorship helps illuminate the dangerous interplay between public desperation, elite miscalculations, and extremist ambition, providing crucial lessons for safeguarding democracy today.

Were The Allied Bombings Of Germany War Crimes? – Mythbusting Berlin

The history of the Allied bombing of Germany during the Second World War still triggers fierce debate. Was reducing cities to rubble a necessary evil – justice from above in a just war – or an unforgivable crime? Can the intentional targeting of civilians ever be justified as militarily necessary?

In a conflict where all rules seemed to vanish, an even more pertinent question persists: by the very standards they would use to judge their

Were The Nazi Medical Experiments Useful? – Mythbusting Berlin

Before the Nazi period, German medicine was considered the envy of the world – a shining monument to progress. But deep within that monument, a rot was spreading, one which would collapse the entire structure into an abattoir. From the wreckage, we are left with a profoundly uncomfortable inheritance: a moral enigma wrapped in doctor’s whites.

What to make of the data, the images, and the terrible knowledge gleaned from unimaginable human suffering. Whether

What Are The Origins Of The Nazi Salute? – Mythbusting Berlin

A specter is haunting the modern mind, a gesture so charged with the dark electricity of history that its mere depiction can unleash a storm of controversy.

It is a simple movement: the right arm, stiff and straight, raised to the sky. But in that simplicity lies a terrifying power, a symbol of a regime that plunged the world into an abyss and a chilling reminder of humanity’s capacity for organised hatred.

This

What Are The Origins Of The Nazi Swastika? – Mythbusting Berlin

Long before the legions of the Third Reich marched beneath its stark, unnerving geometry, the swastika lived a thousand different lives. It was a symbol of breathtaking antiquity, a globetrotting emblem of hope and good fortune that found a home in the most disparate of cultures. To even begin to understand its dark 20th-century incarnation, one must first journey back, not centuries, but millennia.

What Are The Pink Pipes In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

A first-time visitor to Berlin could be forgiven for thinking the city is in the midst of a bizarre art installation. Bright pink pipes, thick as an elephant’s leg, climb out of the ground, snake over pavements, arch across roads, and disappear back into the earth. Are they part of a complex gas network? A postmodern artistic statement? A whimsical navigation system? These theories, all logical, are all wrong. The truth is far more elemental,

What Do The Colours Of The German Flag Symbolise? – Mythbusting Berlin

What does a flag mean? Is it merely a coloured cloth, or does it hold the hopes, struggles, and identity of a nation? The German flag, with its bold stripes of black, red, and gold, is instantly recognisable. But the story of its colours is a tumultuous journey through revolution, suppression, and reinvention. The common explanation for their symbolism is a simple, romantic verse, yet the truth is a far more complex and contested tale,

What Happened To Adolf Hitler’s Alligator? – Mythbusting Berlin

It is often said that you can tell a lot about a person by their relationship with animals; that owners often come to look and behave like their pets. Or is it perhaps more that people choose their pets to correspond to their personality? Nazi leader Adolf Hitler’s love of dogs, for example, is well documented but what is there to make of his relationship with reptiles?

What Happenened To The German Royal Family? – Mythbusting Berlin

When the smoke cleared over the trenches in November 1918, the German Empire had evaporated, and with it, the divine right of the Hohenzollern dynasty. Conventional wisdom suggests the family simply vanished into the sepia-toned obscurity of history books—exiled, forgotten, and irrelevant. But dynasties, like weeds in a landscaped garden, are notoriously difficult to uproot entirely. The story of the German royals did not end with the Kaiser’s flight to Holland; it merely shifted gears.

What Is The Difference Between Fascism & Nazism? – Mythbusting Berlin

While the terms ‘Fascist’ and ‘Nazi’ are often bandied around interchangeably as shorthand for tyranny – Italian fascism and German National Socialism were distinctly different beasts. Albeit ideological kin. One an ideology of state-worship, born from post-war chaos and national pride; the other built upon a fanatical, pseudo-scientific obsession with race. Two peas in the same totalitarian pod – twins in tyranny – more succinctly summarised as the Nazi chicken to the Fascist egg.

What Was Checkpoint Charlie? – Mythbusting Berlin

Checkpoint Charlie remains among Berlin’s most visited historical sites, famed worldwide for its significance during the Cold War. Originally established as a modest border-crossing point, it evolved dramatically over the decades into an international symbol of freedom, espionage, and intrigue. Today, critics and locals often dismiss it as little more than a tourist trap—Berlin’s Disneyland—but how exactly did Checkpoint Charlie get its peculiar name, and what truths hide behind its popularity?

What Was Prussia? – Mythbusting Berlin

Prussia’s legacy is both remarkable and contentious—once a minor duchy, it rose dramatically to shape modern European history. Renowned for military discipline, administrative efficiency, and cultural sophistication, Prussia was instrumental in uniting the German states, laying foundations for a unified Germany. But how did this kingdom, with its roots in Baltic territories, achieve such prominence, and why does its complex history continue to evoke admiration, debate, and occasional discomfort in Germany today?

What Was The Berlin Airlift? – Mythbusting Berlin

In the ruins of 1948, the silence of Berlin was not a sign of peace, but a held breath before a new catastrophe. The city, drowning in rubble and political intrigue, became the staging ground for the twentieth century’s most audacious gamble. While popular history remembers the chocolate parachutes and smiling pilots, the reality of the Berlin Airlift was a terrifying operational nightmare born from a ruthless currency war. It wasn’t just a humanitarian mission;

What Was The Socialist Kiss? – Mythbusting Berlin

It is one of the most curious and enduring images of the Cold War: two middle-aged, grey-suited men, locked in a fervent embrace, their lips pressed together in a kiss of apparent revolutionary passion. This was the ‘Socialist Fraternal Kiss’, a ritual that, for a time, seemed to encapsulate the unwavering solidarity of the Eastern Bloc.

But what was behind this seemingly intimate gesture? Was it a genuine expression of camaraderie, a piece of

Who Built The Berlin Wall? – Mythbusting Berlin

One of the most common questions I have encountered from people curious about Berlin, and often so cryptically phrased. Who built the Berlin Wall? A simple five-word query, yet one that can be read one of two ways. More than thirty years since the ‘Fall of the Wall’, the story of its construction continues to baffle many who are mainly familiar with its existence through knowledge of its importance…

Who Really Raised The Soviet Flag On The Reichstag? – Mythbusting Berlin

One iconic photograph has come to symbolise the Red Army’s victory over Nazi Germany in 1945—the Soviet flag waving triumphantly above Berlin’s battered Reichstag building. Yet behind this enduring image lies controversy, confusion, and political manipulation. Who truly raised the Soviet banner atop the Reichstag? Was it a spontaneous act of heroism or carefully staged Soviet propaganda? Decades later, unraveling the truth reveals surprising layers beneath the mythologized symbol of Soviet triumph.

Who Was Really Responsible For The Reichstag Fire? – Mythbusting Berlin

Various theories have been posited as to who actually set fire to the German parliament in 1933. Was it the opening act in an attempted Communist coup or a calculated false flag operation carried out by elements of the Nazi Party, intended to create the conditions necessary for introducing single-party rule? And what part did the young man from Holland, arrested shirtless inside the building the night of the fire, play in this event?

Who Were The Last Nazis On Trial? – Mythbusting Berlin

More than eighty years after the Holocaust, courtrooms across Germany still echo with testimony from the final chapter of Nazi justice. Centenarian defendants in wheelchairs, their faces hidden behind folders, arrive to answer for crimes committed in their youth. These are not the architects of genocide—those men faced their reckoning at Nuremberg decades ago. These are the guards, the secretaries, the bookkeepers: ordinary people who enabled extraordinary evil. Their trials represent a legal revolution: the

Why Is Berlin The Capital Of Germany? – Mythbusting Berlin

There was little in its humble origins—as a twin trading outpost on a minor European river—to suggest that Berlin was destined for greatness. It sits on the flat expanse of the North European Plain, a landscape once dismissively referred to as the “sandbox of the Holy Roman Empire.” Unlike other world capitals, it lacks breathtaking scenery or a naturally defensible position. It is a city built not on majestic hills or a grand harbour, but