“If we withdraw, we lose Europe. We might as well go home and prepare for the next war.”

General Lucius D. Clay, Military Governor of the US Zone, cabling Washington in 1948

Retrospective views of 1940s Berlin often struggle to penetrate the sheer scale of its physical destruction.

By 1948, the city was not merely broken; it was a landscape of exhaustion, defined by the smell of wet ash and the psychological weight of occupation. The silence that followed the German capitulation had not ushered in peace, but rather a precarious interregnum.

The United States, Britain, France, and the Soviet Union—an alliance of convenience forged solely by a common enemy—found themselves overseeing a void where the Third Reich once stood.

The mistrust was immediate.

The wartime coalition effectively evaporated the moment the firing stopped, replaced by a tense proximity where erstwhile allies operated less as partners and more as antagonistic factions wrestling for the soul of the continent.

Western policy in this period is frequently characteri sed as reactive, a sluggish response to Soviet imperiousness.

This dynamic was cemented early: the Red Army had conquered and occupied Berlin exclusively for two months before Western forces were finally granted access in July 1945.

By the time the Americans and British arrived to claim their sectors, the Soviets had already begun dismantling the industrial base and reshaping the local political apparatus.

Consequently, the Western powers spent the initial occupation years attempting to regain the initiative on ground that had already been seeded by Moscow.

If the unconditional surrender of 1945 marked the funeral of Hitler’s Third Reich, then the Berlin Airlift three years later marked the awkward moment that cautious suspicion escalated into a full-blown Cold War.

–

Berlin - The Ashen Chessboard

“The Soviet zone was not so much occupied as harvested. It was stripped of everything that could be moved, from railway tracks to toilet bowls.”

Tony Judt, author of ‘Postwar’

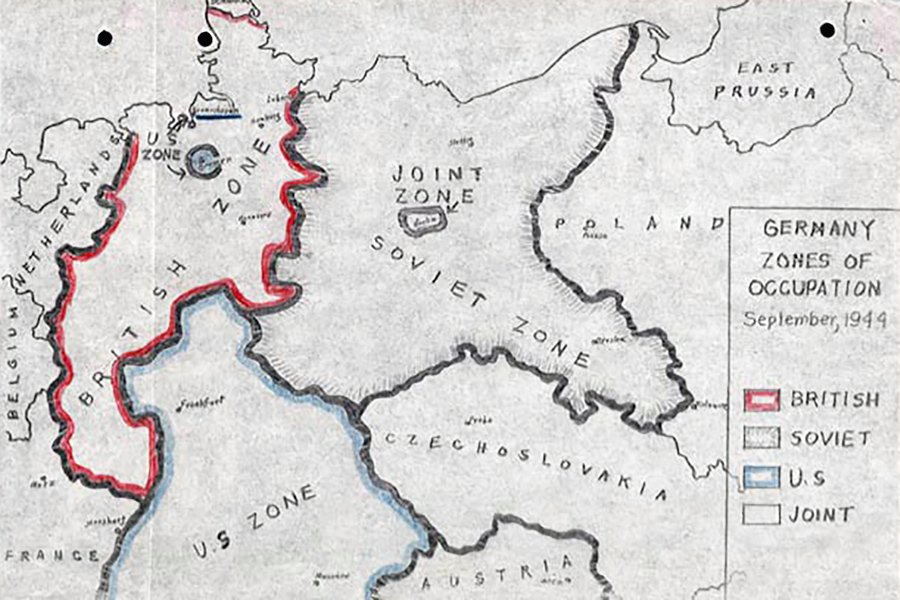

To understand the Airlift, one must first understand the utter strangeness of the geopolitical landscape in 1945.

The end of the Second World War did not bring immediate order; it brought the Allied Control Council and the Kommandatura, bureaucratic entities that were doomed to fail before the ink was dry on the surrender documents.

The victors of the Second World War – the United States, Britain, France, and the Soviet Union – had agreed at Potsdam in the summer of 1945 to administer Germany jointly.

The stated goal was to create a “decentralised, demilitarised, democratised, and denazified” Germany.

It sounds noble on paper.

In reality, it was a four-way marriage of convenience that had turned toxic.

The Illusion of the Blank Canvas

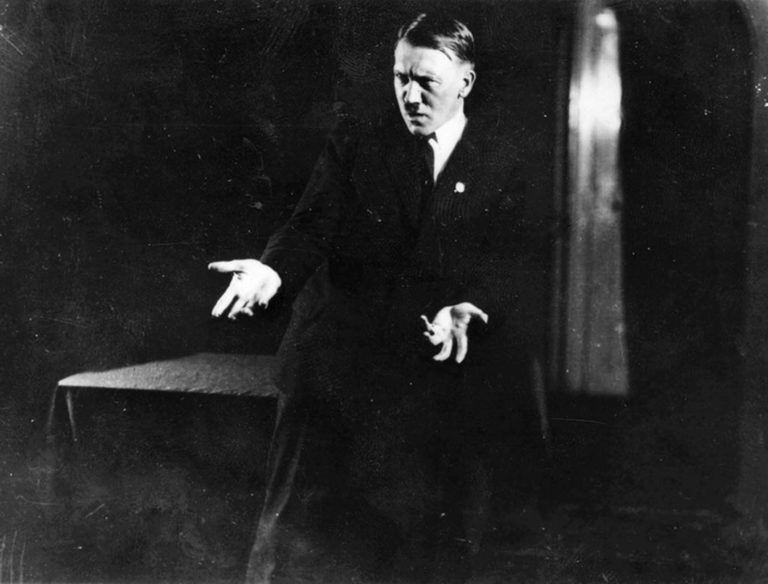

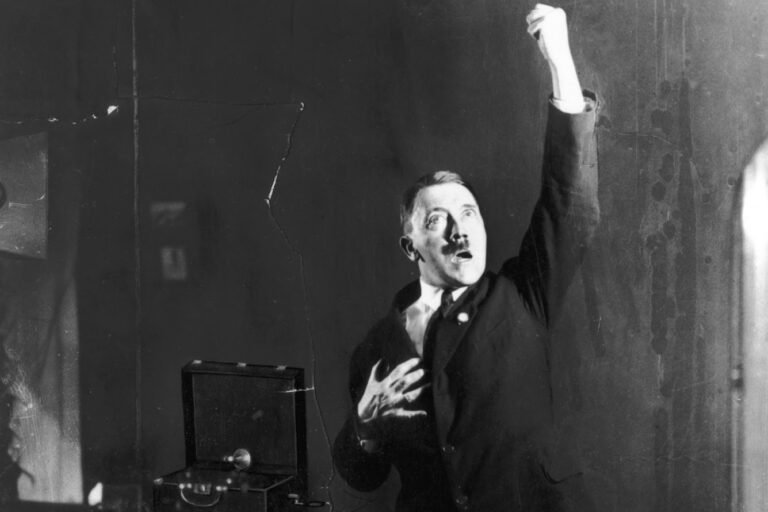

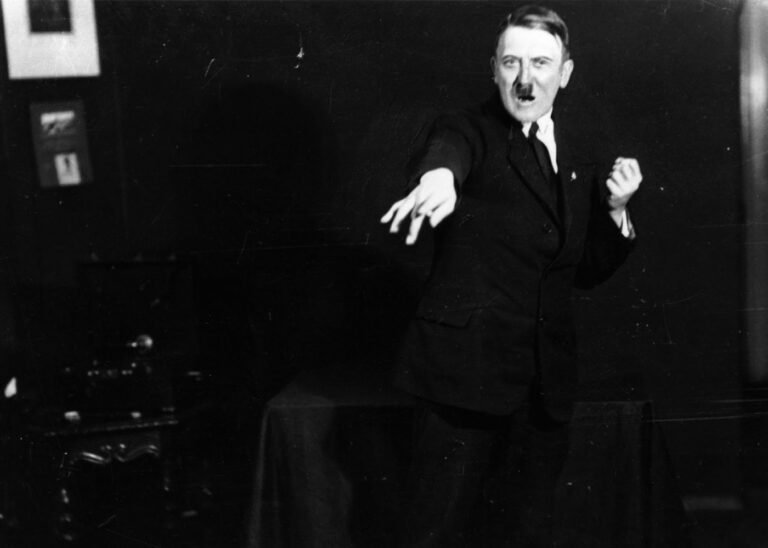

There was a pervasive illusion in 1945 that the total defeat of the Third Reich provided a tabula rasa, a blank canvas upon which a better society could be engineered.

But geography is stubborn.

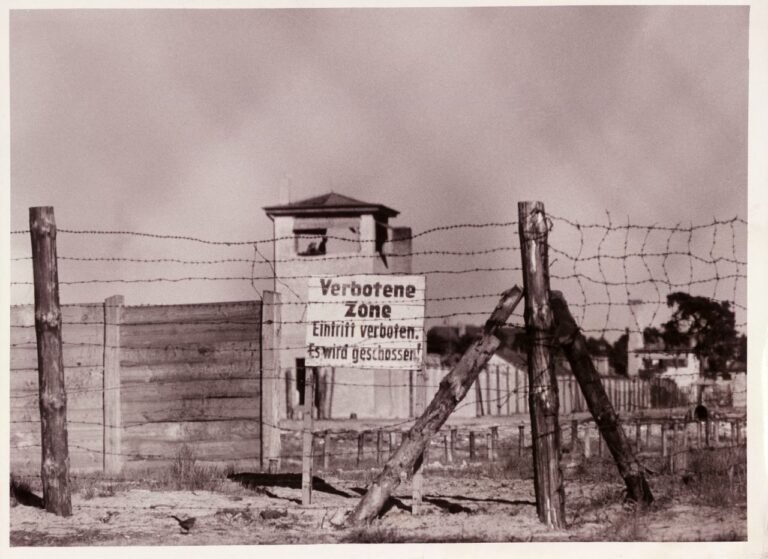

The Soviets had been allocated a zone of occupation that wrapped entirely around Berlin. The Western sectors of the capital were an island of capitalism in a Red Sea.

Stalin’s vision for Germany was contradictory.

Officially, he advocated for a neutral, demilitarised Germany that would serve as a passive buffer zone. However, documents from the Soviet archives, scrutinized by historians like Norman Naimark and Antony Beevor, reveal that the inner circle—including the dreaded Lavrentiy Beria, head of the NKVD, and Foreign Minister Molotov—viewed the Soviet Zone (what would become the DDR) as a resource extraction site.

They wanted a granary and a steel mill for the Motherland.

This exploitation was immediate and brutal.

In the immediate aftermath of the war, while the West dithered on the ‘Morgenthau Plan’ (a vengeful proposal by the US Treasury Secretary to de-industrialise Germany and turn it into a pastoral state, which former President Herbert Hoover horrifiedly noted would require the starvation of 25 million people), the Soviets were already dismantling their zone.

The Reparations Trap

The spectre of the Treaty of Versailles loomed large over the Allied planners.

They remembered how fixed reparation costs (6.6 billion pounds) had destroyed the Weimar economy and arguably paved the way for Hitler.

At Potsdam, they devised a “compromise.” Instead of a lump sum, each occupying power would extract reparations from their own zone.

The catch?

The Soviet zone, while roughly the size of the other zones combined in terms of landmass, was resource-poor. It lacked the coal of the Ruhr or the heavy industry of the Rhineland. To compensate, it was agreed the Soviets would receive 10% of the industrial capital from the Western zones.

In return, the Soviets were supposed to ship food and raw materials from their zone to the West.

It didn’t work.

The Soviet authorities, driven by the need to rebuild a devastated Motherland, engaged in what can only be described as industrial cannibalism.

They stripped the Soviet Zone bare.

Second sets of railway tracks were torn up and shipped east.

Entire factories, down to the toilets and light fittings, were crated up and sent to Russia.

By robbing their own zone of its industrial base, they were crippling its future before it began.

The population dynamics made this even more volatile.

In 1945, the Soviet zone held about 16 million people.

But the demographic pressure was immense.

By 1950, a quarter of the population in the East were Vertriebene—refugees expelled from the former Eastern Territories now claimed by Poland and the USSR.

These were people who had lost everything, arriving in a zone that had nothing.

The Atomic Shadow

A detail often missed in general summaries is the hidden treasure in the Ore Mountains (Erzgebirge) of Saxony and Thuringia.

Just as relations were freezing, the Soviets discovered uranium.

The NKVD seized the area immediately.

In a grim irony of language that would define the era, the mining of uranium for the Soviet atomic bomb project was propaganda-branded as the extraction of ‘Peace Ore’.

It relied on forced labor, transforming East Germany into the fourth-largest producer of uranium in the world, a vital cog in Stalin’s terrifying new military machine.

This was the context in early 1948: a looted East, a nervous West, and a Berlin that was politically split but physically connected.

–

The Berlin Blockade: The Currency of Conflict

“The technical difficulties will continue until the Western powers abandon their plans for a West German government.”

Marshal Vasily Sokolovsky, Soviet Military Governor, June 1948

The Berlin Blockade of 1948 was not triggered by a sudden whim.

It was triggered by money.

The German economy two years after the end of the Second World War was a zombie economy.

The Reichsmark was worthless; the true currency was American cigarettes (specifically Lucky Strikes) and nylon stockings.

Without a stable currency, there was no trade.

Without trade, there was no reconstruction.

The United States, having pivoted away from the punitive Morgenthau Plan to the reconstructionist Marshall Plan (officially the European Recovery Program), knew that West Germany needed a real currency to survive.

The Marshall Plan, announced by George C. Marshall on the steps of Harvard University in 1947, pledged $13 billion to rebuild Europe.

But you cannot rebuild an economy if the money is paper confetti.

‘Operation Bird Dog’ and the Deutsche Mark

In great secrecy, the Western Allies prepared for a currency reform.

They printed crates of new notes—the Deutsche Mark—in the US and shipped them to Frankfurt in boxes labeled ‘Bird Dog’.

On Sunday June 20th 1948, the Western powers introduced the Deutsche Mark in the Trizone (the combined US, UK, and French zones).

Each citizen received 40 D-Marks.

It was an economic miracle overnight.

Shop windows, previously empty as merchants hoarded goods against inflation, suddenly filled with vegetables, tools, and clothes.

The black market collapsed.

Stalin was furious.

He viewed this as a breach of the Potsdam Agreement, which required major decisions to be made jointly. He rightly saw that a revitalized Western Germany, tied to the dollar, would act as a ‘magnet’ pulling the East away from Soviet influence.

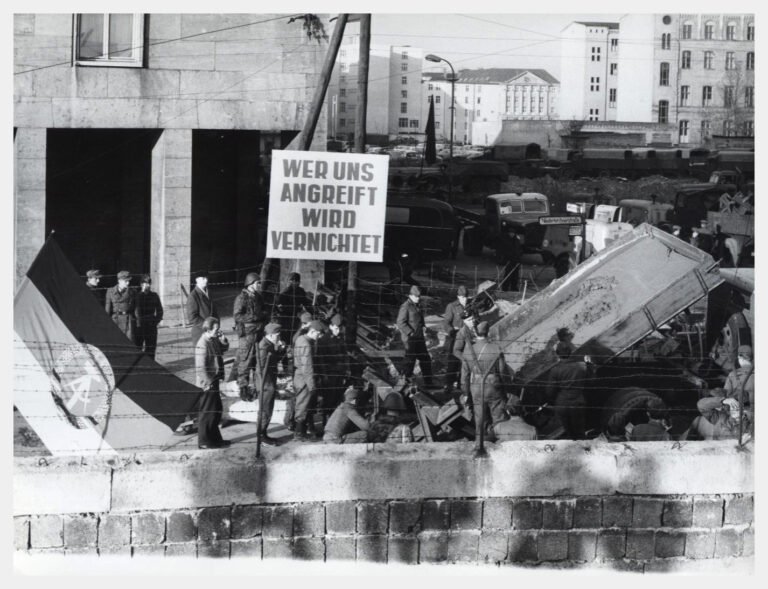

The Tightening Noose

When the Allies signaled their intent to introduce the D-Mark into West Berlin as well, the Soviet bear snapped back.

The blockade began in increments.

First, ‘technical difficulties’ were cited.

A bridge needed repairs. A lock on a canal was broken. A train needed a safety inspection.

By June 24th 1948, the charade ended.

All rail, road, and barge traffic into West Berlin was halted.

The Soviets cut the electricity—this was easy, as the major power plants (like Zschornewitz) were in the Soviet sector or zone. They halted coal shipments.

West Berlin, a city of over 2 million people, was now an island. It had roughly 36 days of food and 45 days of coal.

This leads us to a great ‘What If’ of the mythology of the Berlin Blockade.

There is a misconception that the Allies immediately knew what to do.

They did not.

The initial mood in Washington and London was gloomy.

Many advisors told President Truman and Prime Minister Attlee that Berlin was indefensible. The Soviet army had 300,000 troops ringing the city; the Allies had a token force of roughly 20,000, mostly military police.

General Clay, the American military governor, was a man of steely nerve. He initially proposed an armed convoy to smash through the blockade—a column of tanks driving up the Autobahn.

Washington was horrified; at best this seemed like a recipe for a Third World War.

The alternative seemed to be a humiliating withdrawal.

The Mayor of Berlin (technically the Mayor-elect, thwarted by Soviet veto), Ernst Reuter, made it clear to Clay: “You cannot abandon this city.”

–

The Berlin Airlift: The Logistics Of A Siege

“In 1945, the Americans came to kill. In 1948, they came to save. That psychological shift was the foundation of the modern German-American alliance.”

Andrei Cherny, author of ‘The Candy Bombers’

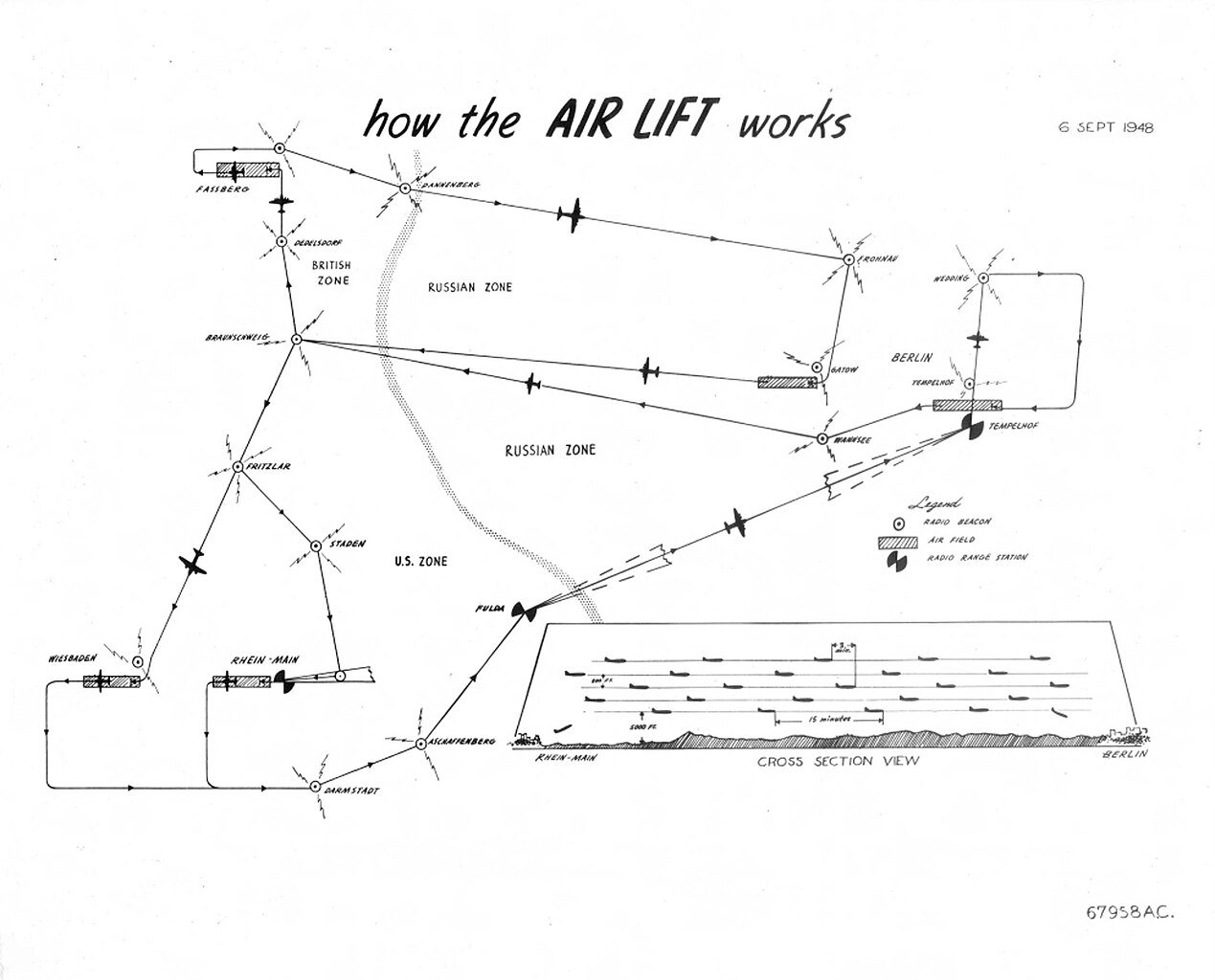

The Berlin Airlift (Operation Vittles for the US, Operation Plainfare for the British) developed out of desperation, not a master plan.

Initially, it was thought to be impossible.

To keep West Berlin alive—not comfortable, just alive—planners estimated the city needed 4,500 tons of supplies per day.

In the summer of 1948, the available Allied air fleets in Europe could barely haul 700 tons.

The math didn’t work.

The Luftwaffe had failed to airlift supplies to the trapped Sixth Army in Stalingrad; how could the Americans expect to succeed here?

Industrial Ballet

What followed was the greatest logistical feat in the history of aviation.

General William H. Tunner, a genius of logistics who had run the ‘Hump’ airlift over the Himalayas during the war, was brought in to discipline the operation.

He turned the skies over Berlin into a conveyor belt. He instituted a rigorous rhythm: a plane would take off every three minutes, fly at a specific altitude, and land at Tempelhof or Gatow airport.

If a pilot missed his approach, he didn’t get a second try; he had to fly the cargo all the way back to West Germany.

The corridors were narrow—only 20 miles wide.

The Soviets harassed the planes. Yakovlev fighters would buzz the slow-moving C-54 Skymasters and C-47 Dakotas. Searchlights would blind pilots at night. Barrage balloons would drift perilously close to the flight paths.

But the Allies didn’t fire back. They just kept flying.

The cargo was unglamorous.

While there was chocolate and luxury, the vast majority of the weight was coal.

It is a dirty, dangerous business flying coal dust in an aircraft; it gets into the instruments, it is flammable, and it is heavy. Sacks of coal, sacks of flour, and dehydrated potatoes—which the Berliners, with their darker sense of humor, despised but ate—filled the fuselages.

The Noise of Freedom

For the Berliners, the Airlift was a sensory assault. The noise was ceaseless.

Imagine living in a neighborhood where a four-engine heavy bomber lands over your roof every 60 seconds, 24 hours a day.

But this noise, previously the prelude to death and destruction, soon transformed into the sound of safety.

When the engines stopped (due to fog), then the terror returned – how would the city survive?

The stats defy belief.

A total of 277,804 planes were flown.

On the busiest day, the ‘Easter Parade’ of April 16th 1949, General Tunner pushed his crews to the breaking point to set a record. They managed 12,941 tons in 24 hours. That’s nearly three times the minimum requirement.

An Allied plane was landing in Berlin almost once every single minute.

The Human Cost and the Black Market

It is a popular myth that the Berlin Airlift solved the hunger completely. Berliners were still freezing. They were chopping down the trees in the Tiergarten for fuel. They were trading family heirlooms for butter.

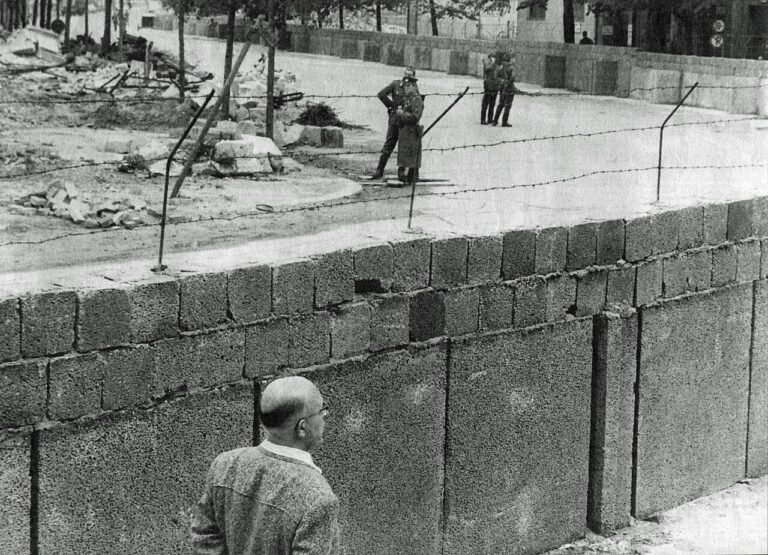

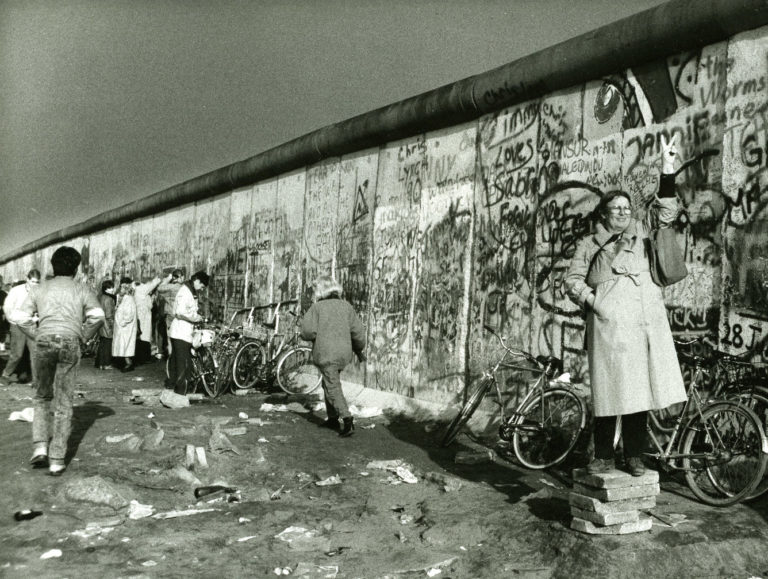

Life in West Berlin was a surreal mix of high geopolitics and grubby survival. Because of the different currency values (The West Mark vs the East Mark), a strange arbitrage economy emerged. Berliners would cross into the East sector (which was still physically open—the Wall wouldn’t be built until 1961) to buy certain goods if they had valid currency.

The S-Bahn trains, controlled by the East German railway (Reichsbahn) even in the West, became vectors of smuggling.

But the Airlift brought in the critical items that the East refused to supply: medical supplies, newsprint for the free press, and coal for the power stations.

Building Tegel: The 90-Day Wonder

One of the great untold stories of the Berlin Airlift is the construction of Tegel Airport.

Tempelhof (in the US sector) and Gatow (in the British sector) were saturation-full. A third airport was needed in the French sector.

The French, having a smaller air force and budget, didn’t have the heavy equipment. So, they hired Berliners. Thousands of German women and men, working for meager rations and pay, built Tegel airport by hand, using crushed rubble from their destroyed city as the foundation for the runway. They built a functional airport in roughly 90 days.

There is a famous anecdote regarding the construction of Tegel.

A Soviet radio tower hampered the approach path. The French commandant asked the Soviets to move it. The Soviets ignored him. So, the French commandant, with a flair for the dramatic, simply dynamited the tower. When the furious Soviet general called to complain, the French commandant reportedly replied, “With the compliments of the French high command.”

The ‘Candy Bomber’ – A Nuanced Heroism

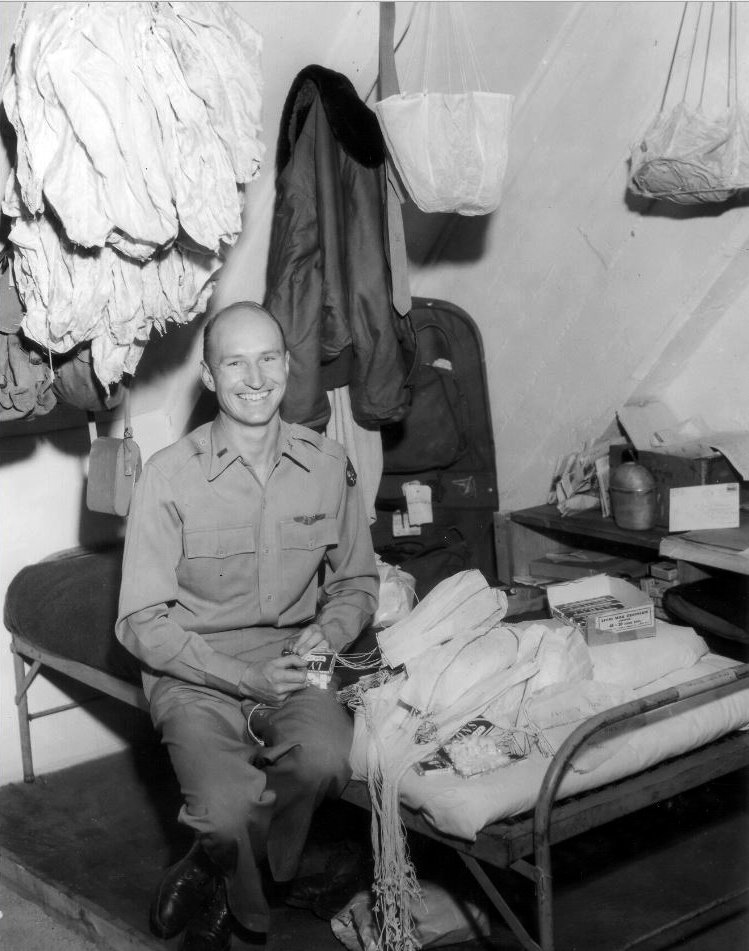

We cannot skip Gail Halvorsen, the famous ‘Candy Bomber’.

But we must place him in context.

Halvorsen started dropping handkerchief-parachutes of gum and chocolate to kids at the fence of Tempelhof on his own initiative. When his superiors found out, they didn’t court-martial him; they capitalised on it.

Operation Little Vittles became a PR masterstroke.

However, focusing solely on Halvorsen risks infantilising the Berlin population. These people weren’t just waiting for chocolate. They were making a hard political choice.

The Soviets offered food rations to any West Berliner who would register their residence in the East.

“Come to us,” the Soviet propaganda said, “and you will eat.”

The amazing fact is that the vast majority of West Berliners refused.

They chose hunger and the Berlin Airlift over succumbing to Soviet administrative control. In the 1948 city council elections (held under the shadow of the blockade), the Communists were trounced. The SPD and Ernst Reuter won a massive mandate. 80% of SPD members in the west had already voted against a merger with the Communist KPD.

The Berliners were not passive victims; they were active participants in their own rescue.

–

The End of the Blockade and German Partition

“Stalin gave us a lesson in unity. He made the Germans and the Allies dependent on each other. He created the West.”

Carlo Schmid, German SPD politician and ‘Father of the Basic Law’

Stalin finally blinked.

The blockade was hurting the Soviet zone more than the West.

The Western counter-blockade had stopped the shipment of steel, chemicals, and specialised equipment from the Ruhr to East Germany. The Soviet zone’s economy, already fragile and looted, began to buckle.

On May 12th 1949, the Soviets lifted the barricades.

The electricity was turned back on. The first British train rolled into Berlin, greeted by hysterical crowds, flowers, and weeping.

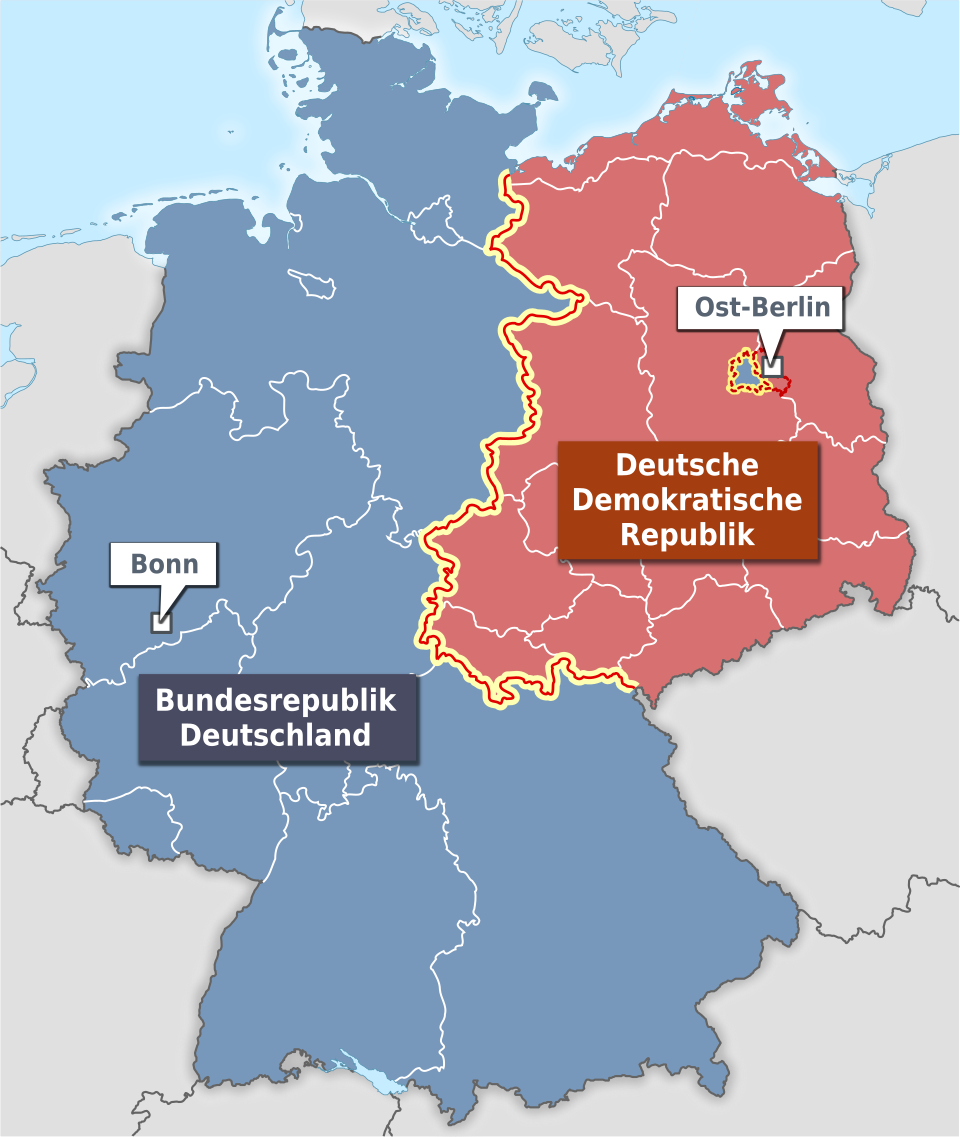

But the ‘victory’ cemented the tragedy.

The magnet theory had proven true, but in a way that shattered the nation. The blockade proved that the two systems could not coexist.

Within weeks of the blockade ending, the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany) was officially founded. The constitution (Basic Law) was ratified.

In response, the German Democratic Republic (DDR) was founded in the East in October 1949.

The timeline is crucial here, often misunderstood by casual readers.

The DDR was not the immediate outcome of the war; it was a reaction to the formation of West Germany.

Stalin had initially hesitated.

He forbade Walter Ulbricht (the German communist leader) from declaring a ‘People’s Republic’ too early. He waited to see if he could keep a neutralised, unified Germany.

Only when the West committed to the FRG did Stalin give Ulbricht, Pieck, and Grotewohl the green light in Moscow on September 27th 1949.

–

Conclusion

“The Berlin Airlift was not just a humanitarian mission; it was the greatest logistical achievement in the history of aviation, and the first battle won by the West without firing a shot.”

General Lucius D. Clay, writing in his memoirs

So, what was the Berlin Airlift?

Essentially a desperate logistical counter-move to the Soviet Union’s total blockade of all land and water access to West Berlin, it was not merely a delivery of milk and flour. It was the moment the Second World War truly ended and the Cold War began. It was the moment the United States ceased to be an occupier in the eyes of the German people and became a protector. It was a psychological pivot of massive proportions.

The operation transformed the city from a passive spoil of war into the active center of a global ideological struggle. It was the moment where the geopolitical tectonic plates finally snapped; the uneasy stillness of the occupation was replaced by a round-the-clock aerial campaign that would define the endurance of the Western alliance.

The Berlin Airlift dispelled the myth of ‘Stunde Null’ (Hour Zero)—the idea that 1945 wiped the slate clean. The blockade showed that the ghosts of history, the mechanics of great power rivalry, and the struggle for resources were still driving forces.

It solidified the division of Europe. It led directly to the formation of NATO (1949) and eventually the Warsaw Pact. It transformed West Berlin from a conquered enemy capital into the ‘frontier city’ of freedom—a reputation that would culminate in Kennedy’s “Ich bin ein Berliner” speech a decade later.

But perhaps most importantly, the Airlift proved the resilience of the human spirit—not just the pilots who flew to the point of exhaustion (claiming 79 lives in crashes), but the Berliners themselves. They survived on dried potatoes and stubbornness, refusing to trade their political autonomy for a Soviet ration card.

The popular mythology of the Berlin Airlift tends to flatten the complexity of the context of the time, however, into a Manichaean East/West struggle: a sudden, capricious siege by Joseph Stalin countered by the moral clarity of the Western democracies.

We gravitate toward the narrative of the ‘Candy Bombers’ because it offers a clear distinction between heroism and villainy. However, the historical reality is far more intricate than newsreel propaganda suggests.

The Blockade did not occur in a vacuum; it was the kinetic conclusion to a prolonged game of economic brinkmanship. It was the result of the Western decision to weaponise currency against the Soviet zone, testing the ‘Magnet Theory’—the belief that a prosperous, capitalist West would inevitably destabilize the East—against the Soviet capacity for brutality.

Before the logistical miracle of the air corridors was established, the loss of Berlin was viewed by many in Washington and London as a foregone conclusion.

General Lucius D. Clay, the American military governor, presided over an island of ruin, isolated deep within hostile territory and surrounded by 300,000 Soviet troops. With 55 million cubic meters of rubble still choking the streets, Clay’s map offered no easy exits, only a stark choice between humiliation and escalation.

Thus, the history of the Airlift is not simply the story of how a city was fed.

It is the story of the specific moment—born of miscalculation, currency reform, and ideological rigidness—when the division of Germany was rendered permanent.

***

If you’ve enjoyed reading this article, consider booking one of our private guided tours of Berlin.

Bibliography

Applebaum, Anne (2012), Iron Curtain: The Crushing of Eastern Europe, 1944–1956, Doubleday

Beevor, Antony (2002), Berlin: The Downfall 1945, Viking. ISBN 978‑0141032399

Cherny, Andrei (2008), The Candy Bombers: The Untold Story of the Berlin Airlift and America’s Finest Hour, G.P. Putnam’s Sons. ISBN 978‑0425227718

Collier, Richard (1978), Bridge Across the Sky: The Berlin Blockade and Airlift, 1948–1949

Giangreco, D. M.; Griffin, Robert E. (1988), Airbridge to Berlin: The Berlin Crisis of 1948, Its Origins and Aftermath

Judt, Tony (2005), Postwar: A History of Europe Since 1945, Penguin Press. ISBN 978‑0143037750

Kempe, Frederick (2011), Berlin 1961: Kennedy, Khrushchev, and the Most Dangerous Place on Earth, G.P. Putnam’s Sons.

Leffler, Melvyn P. (2007), For the Soul of Mankind: The United States, the Soviet Union, and the Cold War, Hill & Wang. ISBN 978‑0‑8090‑9717‑3

Miller, Roger G. (2000), To Save A City: The Berlin Airlift, 1948–1949

Milton, Giles (2021), Checkmate in Berlin: The Cold War Showdown that Shaped the Modern World, ISBN 978‑1‑5293‑9317‑0

Richie, Alexandra (1998), Faust’s Metropolis: A History of Berlin, Carroll & Graf.

Smyser, W. R. (1999), From Yalta to Berlin: The Cold War Struggle Over Germany

Taylor, Frederick (2006), The Berlin Wall: A World Divided, 1961‑1989, HarperCollins.

Tusa, Ann & Tusa, John (1988), The Berlin Airlift

Turner, Barry (2017), The Berlin Airlift: The Relief Operation that Defined the Cold War

HISTORICAL ARTICLES

Mythbusting Berlin

Are There Any Nazi Statues Left In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

Visitors to Berlin often arrive expecting to find the physical remnants of the tyranny of the 20th century still standing – statues of dictators, triumphal arches, or bronze idols. Instead, they often find none. The stone symbols and statues of the Third Reich are still gazing down on them, however, hiding in plain sight. But why are there no statues of Hitler? Did the Allies destroy them all in 1945, or is the truth stranger

Could The Western Allies Have Captured Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

To contemplate a Western Allied capture of Berlin in 1945 is to challenge the established endgame of the Second World War. What was the true military and logistical feasibility of a Western Allied assault on the Nazi capital? What factors truly sealed Berlin’s fate, and what might have changed had the Allies pushed eastward?

Answering these questions means delving into the complex interplay of logistics, political maneuvering, and the competing visions for a post-war world

Did Any Of The Rothschild Dynasty Die In The Holocaust? – Mythbusting Berlin

The Rothschild name is synonymous with immense wealth, influence, and persistent conspiracy theories—especially during the era of Nazi Germany. Often targeted by antisemitic propaganda, the family’s survival during World War II has sparked myths about their supposed immunity from Nazi persecution. But did any Rothschild family member actually perish in the Holocaust? This article explores that compelling question, unraveling historical misconceptions and revealing the reality behind one of Europe’s most famous dynasties.

Did Frederick The Great Introduce The Potato To Germany? – Mythbusting Berlin

One of the more bizarre claims to fame attributed to the first King of Prussia is that the man who would go down in history known as Frederick the Great introduced the potato to Germany during his reign back in the 1700s. This starchy root vegetable has undoubtedly become a staple part of German cuisine – an essential addition to any plate of Schnitzel, Schweinshaxn, and Königsberger Klopse – however, whether Frederick the Great is

Did Hitler Escape To Argentina In 1945? – Mythbusting Berlin

Although Nazi leader, Adolf Hitler, certainly remains an inescapable figure, could there be any truth to the story of his escape to Argentina in 1945? That the most wanted man on earth could simply vanish, to spend the rest of his life peacefully in South American obscurity captivates imaginations. Yet, despite numerous investigations, this tale persists primarily as myth—fueled by speculation, hearsay, and conspiracy theories.

Did Hugo Boss Design The Nazi Uniforms? – Mythbusting Berlin

The idea that Hugo Boss – the man whose name now adorns expensive suits and fragrances – was the creative genius behind the Nazi uniforms suggests a terrifying collision of haute couture and holocaust – a marriage of high style and high crimes. The image is striking: a German tailor sketching the ultimate villain’s costume. But history, as usual, is far messier, more bureaucratic, and more banal than the internet memes suggest. To understand who

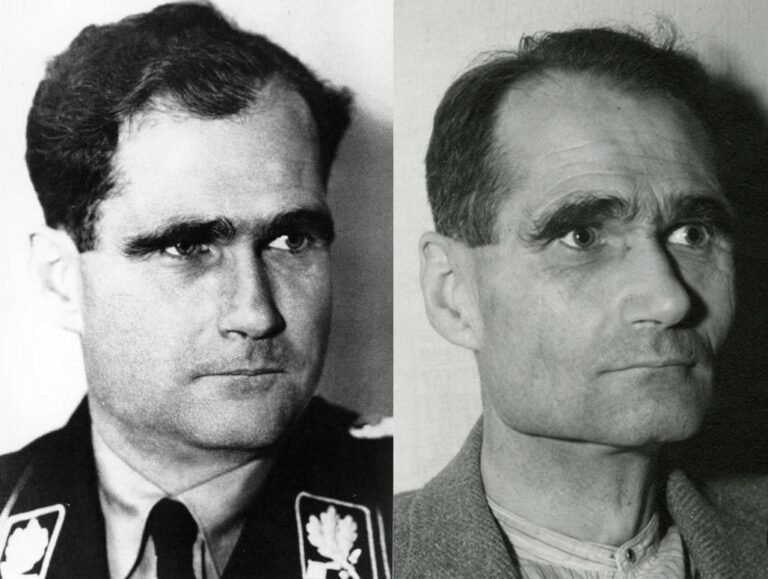

Did Rudolf Hess Really Commit Suicide? – Mythbusting Berlin

On a summer’s day in 1987, the last Nazi war criminal of the Nuremberg trials was found dead in a prison built for hundreds, yet for two decades, housed only him. The official verdict was suicide, a straightforward end to a life defined by fanaticism, delusion, and contradiction.

But the simplicity of the report belied the complexity of the man and the 46 years he had spent in Allied custody. In the meticulously controlled

Did The Nazis Develop Nuclear Weapons? – Mythbusting Berlin

The Nazi obsession with super-weapons became so serious in the closing stages of the Second World that Adolf Hitler personally believed that such ‘Wunderwaffen’ both existed in a usable form – and would save the country from defeat. Had the Nazis managed to develop nuclear weapons by 1945 – the outcome of the war would surely have been different. But how close were Hitler, Himmler, and his henchmen to developing an A-bomb?

Did The Nazis Invent Decaf Coffee? – Mythbusting Berlin

Persistent rumors claim that Nazis preferred their coffee anything but pure, leading some to wonder if they might have influenced the development of decaffeinated coffee. Although decaf was already widely available across Europe by the mid-20th century, speculation continues: could the Nazis really have played a role in popularizing—or even discovering—this caffeine-free alternative, or is this simply another caffeinated conspiracy cooked up to sensationalize an ordinary historical detail?

Did The Nazis Invent The Bicycle Reflector? – Mythbusting Berlin

The fruits of wartime ingenuity are plenty – so many, in-fact, that it has become somewhat of a worn cliche that as the guns start firing the innovators get to work, often solving problems while providing more problems for the enemy to overcome.The kind of progress that results in the production of newer improved, more lethal weapons, such as to increase the chances of victory.

Did The Nazis Run The Largest Counterfeiting Operation In History? – Mythbusting Berlin

During the Second World War the Nazis masterminded an astonishing plot to destabilise Britain by flooding its economy with counterfeit banknotes. Crafted in secret by concentration camp prisoners, this forged fortune became the most ambitious counterfeiting operation ever attempted. But was it history’s largest? Dive into the extraordinary tale of Operation Bernhard,

rife with deception, survival, and intrigue—revealing the truth behind one of the Third Reich’s most audacious schemes and its surprising legacy.

Did The Second World War End In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

When is a war ever truly over? When the last shot is fired in anger would seem like the best measure. Rarely, though, is it possible to gain insight into such a moment.

Remarkably, a record still exists of such a moment at the end of the First World War on the Western Front. A seismic register and recording of the last belching battery of British guns firing artillery across no-man’s-land, followed by a profound

Did The Spanish Flu Pandemic Help The Nazis Take Power? – Mythbusting Berlin

The devastating Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918-1919 struck amid Germany’s post-war turmoil, compounding social instability, economic hardship, and widespread political disillusionment. Could this catastrophic health crisis have indirectly paved the way for Nazi ascension? While often overshadowed by war and revolution, the pandemic’s profound psychological and societal impacts arguably contributed to the perfect storm, enabling extremist ideologies—including Nazism—to gain popularity and ultimately seize power in a fractured Germany.

Have Adolf Hitler’s Remains Been DNA Tested? – Mythbusting Berlin

In the smouldering ruins of Berlin in 1945, the world’s most wanted man vanished. Did Adolf Hitler, as official history attests, die by his own hand in the Führerbunker? Or did he escape, fuelling a thousand conspiracy theories that have echoed for decades? For years, the Soviets claimed to hold the gruesome proof of his death: a skull fragment and a set of teeth, locked away in Moscow archives. But in an age of definitive

How Did The Nazi Concentration Camps Differ From The Soviet GULAG?

The Nazi concentration camps and Soviet Gulag system have often been conflated in popular imagination—twin symbols of twentieth-century totalitarian horror. Yet the two systems operated on fundamentally different principles. One extracted labor to fuel industrialisation while accepting mass death as collateral damage; the other evolved into purpose-built machinery of genocide. Understanding these distinctions isn’t merely academic—it reveals how different ideologies produce different atrocities, and why Germany and Russia reckon with these legacies so differently today.

How Long Did It Take To Build The Berlin Wall? – Mythbusting Berlin

It is one of the most enduring images of the 20th century: a city divided overnight. The popular narrative tells us that Berliners went to sleep in a unified city and woke up in a prison. While the shock of August 13th 1961, was very real, the idea that the ‘Wall’ appeared instantly is a historical illusion. The physical scar that bisected Berlin was not a static creation, but a living, malevolent beast that evolved

How Many Assassination Attempts On Adolf Hitler Were There? – Mythbusting Berlin

Nazi leader, Adolf Hitler, projected an aura of invincibility, a man of destiny shielded by providence. But behind the carefully constructed image of the untouchable Führer lies a story of constant threat, of bombs that failed to detonate, and errant bullets that missed their mark. Unearth the hidden history of the numerous attempts on Hitler’s life as we explore the courage of those who tried to change the course of history and the devil’s luck

How Many Jews Died In The Holocaust? – Mythbusting Berlin

The answer to the question posed of how many Jews died in the Holocaust is a simple one: too many. That merely one death was an unforgivable obscenity is a fundamental and necessary realisation in understanding the capriciousness of this unparalleled racial genocide. To comprehend, however, the full number of Jews murdered in Europe by the Nazi regime in the 1930s and 1940s is a detective story of epic proportions: the evidence overwhelming, multifaceted, and

How Many People Died Trying To Escape East Germany? – Mythbusting Berlin

The image of the Berlin Wall is seared into our collective memory, a concrete symbol of Cold War oppression. We think of the daring escapes and the tragic deaths of those who failed. But that well-known number is only a fraction of the truth. The story of those who died trying to escape East Germany is far broader and more complex than most imagine, stretching along a thousand-kilometer border and out into the cold waters

How Old Is Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

A relatively new arrival in Europe, Berlin is over 1000 years younger than London, nevermind Rome or Athens, Jerusalem or Jericho. Just how old is Berlin though?

A question fraught with false assumptions and distortions – that has more often than not been answered with propaganda as it has with the cold hard truth.

Was Adolf Hitler A Drug Addict? – Mythbusting Berlin

Solving the enigma of the ‘Führer’ has become a preoccupation for many, since the arrival of the Austrian-German onto the world stage – although moving beyond the mythology without falling into the trap of prejudically extrapolating on the psychopathography of Hitler or demonising so as to excuse his actions has proven problematic. What to make of the man who became more than the sum of his masks? The painter; the military dilettante, the mass murderer,

Was Adolf Hitler A Freemason? – Mythbusting Berlin

History abhors a vacuum, but adores a mystery. Such is the speculative fiction suggesting a secret allegiance behind the rise of the Third Reich – that the catastrophe of the Second World War was orchestrated from the shadows of a Masonic lodge. The image of Adolf Hitler—the drifter from Vienna turned dictator—as a covert initiate of the very brotherhood he publicly reviled, however, creates a paradox that collapses under scrutiny. As when we unlock the

Was Adolf Hitler Gay? – Mythbusting Berlin

In the shadowy corridors of Third Reich history, few questions provoke as much tabloid curiosity and scholarly exasperation as the sexuality of Adolf Hitler. For decades, rumors have swirled—whispered by political enemies in 1930s Munich, psychoanalyzed by American spies in the 1940s, and sensationalized by revisionist authors today. Was the dictator who condemned thousands of men to concentration camps for “deviant” behavior hiding a secret of his own? By peeling back the layers of propaganda,

Was Adolf Hitler Jewish? – Mythbusting Berlin

Was the dictator who orchestrated the murder of millions of European Jews secretly one of them? It is perhaps the darkest irony imaginable, a story whispered for decades in backrooms, bars, and conspiracy forums alike. The most-common rumour – the ‘Frankenberger Myth’ – suggests that Adolf Hitler’s paternal grandfather was Jewish, a secret so damaging it could have unraveled the entire Nazi regime. But where does this claim come from? And, more importantly, is there

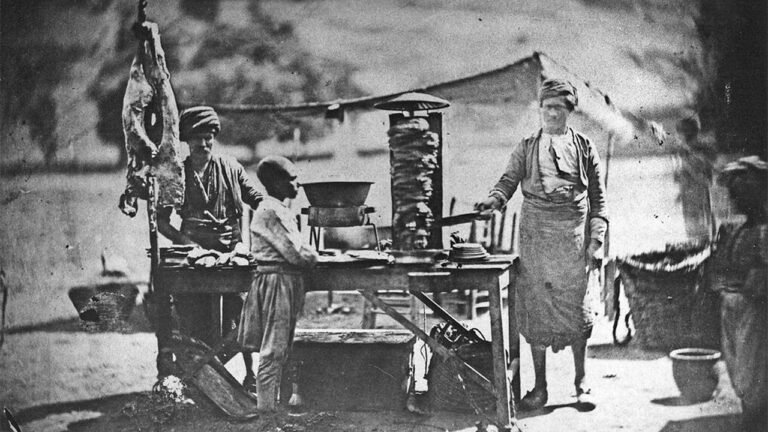

Was Currywurst Invented In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

Explore the story behind what many consider Berlin’s most iconic snack—the ever-so-humble Currywurst. Often hailed as an enduring symbol of culinary creativity amid Cold War scarcity, this humble dish has inspired fierce debate about its true origin. But was it genuinely invented here in Berlin, or have proud locals simply adopted and elevated this spicy street-food favorite into legendary status all their own?

Was Fanta Invented By The Nazis? – Mythbusting Berlin

As one of the most secretive organisations in the world, the Coca Cola corporation refuses to share its secret recipe with anyone. Famously insisting only on shipping the base syrup of its drinks to plants around the world to be carbonated and distributed.

This combined with the trade limitations of the Second World War may have led to the introduction of one of the most popular soft-drinks in the world. But could it be true:

Was Frederick The Great Gay? – Mythbusting Berlin

Frederick II of Prussia, better known as Frederick the Great, is often remembered as the archetypal enlightened monarch – a brilliant military commander, patron of the arts, and learned philosopher. Yet behind the stern portraits of this 18th-century warrior-king lies a personal life long shrouded in intrigue and speculation. Intrigue around the king’s sexual orientation has persisted through the centuries, chiefly revolving around one question: Was Frederick the Great gay?

Was Henry Ford A Nazi? – Mythbusting Berlin

US auto tycoon, Henry Ford, holds the ignominious distinction of being the only American Adolf Hitler praised by name in his National Socialist manifesto: ‘Mein Kampf’. This was not, as it turns out, the only connection between Ford and the Party of Hitler, Himmler, and the Holocaust.

Ford’s overt affinity with the Third Reich reveals a troubling past. How deep these connections ran, and how consequential they were for both sides, is a chapter

Was The Colour Blue Invented In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

Tracing the true history of blue—from ancient Egyptian dyes to the accidental discovery of Prussian Blue in a Berlin lab. We’ll debunk myths about seeing blue, explore colonial indigo plantations, scale mountains with a cyanometer, and trace Van Gogh’s starry skies—all to answer one question: how did Berlin shape our understanding of the world’s rarest color?

Was The Döner Kebab Invented In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

Unlikely icon of immigrant success; fast food symbol of the working class; over-hyped midnight disco eat; or culturally appropriated cuisine? Its influence goes far beyond layers of seasoned meat and fresh vegetables stuffed into pita bread. But does Berlin deserve credit as the Döner Kebab’s true birthplace, or has the city merely refined and popularized a culinary tradition imported from elsewhere?

Was The Fall Of The Berlin Wall An Accident? – Mythbusting Berlin

On a seasonally crisp night in November 1989, one of the most astonishing events of the 20th century occurred. After twenty eight years, three months, and twenty eight days of defining and dividing the German capital, the Berlin Wall ceased to exist – at least in an abstract sense. Although the removal of this symbol of the failure of the East German system would take some time, its purpose – as a border fortification erected

Was The Nazi Party Democratically Elected? – Mythbusting Berlin

The myth persists that Adolf Hitler rose to power through popular democratic choice. Yet history reveals a darker, more complicated truth. Hitler’s ascent involved exploiting democratic institutions, orchestrating violence, propaganda, and political intrigue—not a simple election victory. Understanding how Germany’s democracy collapsed into dictatorship helps illuminate the dangerous interplay between public desperation, elite miscalculations, and extremist ambition, providing crucial lessons for safeguarding democracy today.

Were The Allied Bombings Of Germany War Crimes? – Mythbusting Berlin

The history of the Allied bombing of Germany during the Second World War still triggers fierce debate. Was reducing cities to rubble a necessary evil – justice from above in a just war – or an unforgivable crime? Can the intentional targeting of civilians ever be justified as militarily necessary?

In a conflict where all rules seemed to vanish, an even more pertinent question persists: by the very standards they would use to judge their

Were The Nazi Medical Experiments Useful? – Mythbusting Berlin

Before the Nazi period, German medicine was considered the envy of the world – a shining monument to progress. But deep within that monument, a rot was spreading, one which would collapse the entire structure into an abattoir. From the wreckage, we are left with a profoundly uncomfortable inheritance: a moral enigma wrapped in doctor’s whites.

What to make of the data, the images, and the terrible knowledge gleaned from unimaginable human suffering. Whether

What Are The Origins Of The Nazi Salute? – Mythbusting Berlin

A specter is haunting the modern mind, a gesture so charged with the dark electricity of history that its mere depiction can unleash a storm of controversy.

It is a simple movement: the right arm, stiff and straight, raised to the sky. But in that simplicity lies a terrifying power, a symbol of a regime that plunged the world into an abyss and a chilling reminder of humanity’s capacity for organised hatred.

This

What Are The Origins Of The Nazi Swastika? – Mythbusting Berlin

Long before the legions of the Third Reich marched beneath its stark, unnerving geometry, the swastika lived a thousand different lives. It was a symbol of breathtaking antiquity, a globetrotting emblem of hope and good fortune that found a home in the most disparate of cultures. To even begin to understand its dark 20th-century incarnation, one must first journey back, not centuries, but millennia.

What Are The Pink Pipes In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

A first-time visitor to Berlin could be forgiven for thinking the city is in the midst of a bizarre art installation. Bright pink pipes, thick as an elephant’s leg, climb out of the ground, snake over pavements, arch across roads, and disappear back into the earth. Are they part of a complex gas network? A postmodern artistic statement? A whimsical navigation system? These theories, all logical, are all wrong. The truth is far more elemental,

What Do The Colours Of The German Flag Symbolise? – Mythbusting Berlin

What does a flag mean? Is it merely a coloured cloth, or does it hold the hopes, struggles, and identity of a nation? The German flag, with its bold stripes of black, red, and gold, is instantly recognisable. But the story of its colours is a tumultuous journey through revolution, suppression, and reinvention. The common explanation for their symbolism is a simple, romantic verse, yet the truth is a far more complex and contested tale,

What Happened To Adolf Hitler’s Alligator? – Mythbusting Berlin

It is often said that you can tell a lot about a person by their relationship with animals; that owners often come to look and behave like their pets. Or is it perhaps more that people choose their pets to correspond to their personality? Nazi leader Adolf Hitler’s love of dogs, for example, is well documented but what is there to make of his relationship with reptiles?

What Happenened To The German Royal Family? – Mythbusting Berlin

When the smoke cleared over the trenches in November 1918, the German Empire had evaporated, and with it, the divine right of the Hohenzollern dynasty. Conventional wisdom suggests the family simply vanished into the sepia-toned obscurity of history books—exiled, forgotten, and irrelevant. But dynasties, like weeds in a landscaped garden, are notoriously difficult to uproot entirely. The story of the German royals did not end with the Kaiser’s flight to Holland; it merely shifted gears.

What Is The Difference Between Fascism & Nazism? – Mythbusting Berlin

While the terms ‘Fascist’ and ‘Nazi’ are often bandied around interchangeably as shorthand for tyranny – Italian fascism and German National Socialism were distinctly different beasts. Albeit ideological kin. One an ideology of state-worship, born from post-war chaos and national pride; the other built upon a fanatical, pseudo-scientific obsession with race. Two peas in the same totalitarian pod – twins in tyranny – more succinctly summarised as the Nazi chicken to the Fascist egg.

What Was Checkpoint Charlie? – Mythbusting Berlin

Checkpoint Charlie remains among Berlin’s most visited historical sites, famed worldwide for its significance during the Cold War. Originally established as a modest border-crossing point, it evolved dramatically over the decades into an international symbol of freedom, espionage, and intrigue. Today, critics and locals often dismiss it as little more than a tourist trap—Berlin’s Disneyland—but how exactly did Checkpoint Charlie get its peculiar name, and what truths hide behind its popularity?

What Was Prussia? – Mythbusting Berlin

Prussia’s legacy is both remarkable and contentious—once a minor duchy, it rose dramatically to shape modern European history. Renowned for military discipline, administrative efficiency, and cultural sophistication, Prussia was instrumental in uniting the German states, laying foundations for a unified Germany. But how did this kingdom, with its roots in Baltic territories, achieve such prominence, and why does its complex history continue to evoke admiration, debate, and occasional discomfort in Germany today?

What Was The Berlin Airlift? – Mythbusting Berlin

In the ruins of 1948, the silence of Berlin was not a sign of peace, but a held breath before a new catastrophe. The city, drowning in rubble and political intrigue, became the staging ground for the twentieth century’s most audacious gamble. While popular history remembers the chocolate parachutes and smiling pilots, the reality of the Berlin Airlift was a terrifying operational nightmare born from a ruthless currency war. It wasn’t just a humanitarian mission;

What Was The Socialist Kiss? – Mythbusting Berlin

It is one of the most curious and enduring images of the Cold War: two middle-aged, grey-suited men, locked in a fervent embrace, their lips pressed together in a kiss of apparent revolutionary passion. This was the ‘Socialist Fraternal Kiss’, a ritual that, for a time, seemed to encapsulate the unwavering solidarity of the Eastern Bloc.

But what was behind this seemingly intimate gesture? Was it a genuine expression of camaraderie, a piece of

Who Built The Berlin Wall? – Mythbusting Berlin

One of the most common questions I have encountered from people curious about Berlin, and often so cryptically phrased. Who built the Berlin Wall? A simple five-word query, yet one that can be read one of two ways. More than thirty years since the ‘Fall of the Wall’, the story of its construction continues to baffle many who are mainly familiar with its existence through knowledge of its importance…

Who Really Raised The Soviet Flag On The Reichstag? – Mythbusting Berlin

One iconic photograph has come to symbolise the Red Army’s victory over Nazi Germany in 1945—the Soviet flag waving triumphantly above Berlin’s battered Reichstag building. Yet behind this enduring image lies controversy, confusion, and political manipulation. Who truly raised the Soviet banner atop the Reichstag? Was it a spontaneous act of heroism or carefully staged Soviet propaganda? Decades later, unraveling the truth reveals surprising layers beneath the mythologized symbol of Soviet triumph.

Who Was Really Responsible For The Reichstag Fire? – Mythbusting Berlin

Various theories have been posited as to who actually set fire to the German parliament in 1933. Was it the opening act in an attempted Communist coup or a calculated false flag operation carried out by elements of the Nazi Party, intended to create the conditions necessary for introducing single-party rule? And what part did the young man from Holland, arrested shirtless inside the building the night of the fire, play in this event?

Who Were The Last Nazis On Trial? – Mythbusting Berlin

More than eighty years after the Holocaust, courtrooms across Germany still echo with testimony from the final chapter of Nazi justice. Centenarian defendants in wheelchairs, their faces hidden behind folders, arrive to answer for crimes committed in their youth. These are not the architects of genocide—those men faced their reckoning at Nuremberg decades ago. These are the guards, the secretaries, the bookkeepers: ordinary people who enabled extraordinary evil. Their trials represent a legal revolution: the

Why Is Berlin The Capital Of Germany? – Mythbusting Berlin

There was little in its humble origins—as a twin trading outpost on a minor European river—to suggest that Berlin was destined for greatness. It sits on the flat expanse of the North European Plain, a landscape once dismissively referred to as the “sandbox of the Holy Roman Empire.” Unlike other world capitals, it lacks breathtaking scenery or a naturally defensible position. It is a city built not on majestic hills or a grand harbour, but