“Mercy to the guilty is cruelty to the innocent.”

Adam Smith

The doorbell rang on a quiet street in the New York borough of Queens on a spring afternoon in 1964.

When Hermine Braunsteiner-Ryan answered, she found herself face-to-face with Joseph Lelyveld, a cub reporter from The New York Times. It was the second doorbell he had rung that day.

“My God, I knew this would happen,” she said. “You’ve come.”

Her husband, Russell Ryan, a construction worker who had met his Austrian wife while stationed in Germany, would later protest his wife’s innocence. “My wife, sir, wouldn’t hurt a fly,” he insisted. “There’s no more decent person on this earth.”

The neighbours who knew the fastidious housewife as a friendly presence on 72nd Street had no idea of the nickname prisoners at the Nazi concentration camp of Majdanek had given Braunsteiner-Ryan two decades earlier: the ‘Stomping Mare’.

Survivors testified that she had trampled prisoners to death with her jackboots, thrown children by their hair onto trucks bound for gas chambers, and selected thousands for execution with casual brutality.

Braunsteiner-Ryan’s discovery came through a remarkable chain of coincidences.

Nazi hunter Simon Wiesenthal was dining at a Tel Aviv restaurant when he received a phone call. The maître d’hôtel announcing “phone call for Mr. Wiesenthal” across the dining room led to his recognition by other patrons, who stood and applauded. When he returned to his table, several Majdanek survivors were waiting to tell him about a female guard who had escaped justice.

Following their leads from Vienna to Halifax to Toronto and finally to Queens, Wiesenthal alerted the New York Times, setting in motion events that would make Braunsteiner-Ryan the first Nazi war criminal extradited from the United States.

Her story reveals a fundamental truth about Nazi justice: it has always been incomplete, belated, and often accidental.

The legal reckoning with the Third Reich did not end at Nuremberg in 1946.

It did not conclude with the capture of Adolf Eichmann in Buenos Aires in 1960, nor with the Frankfurt Auschwitz Trials of the 1960s.

Instead, it continues still today—in German courtrooms where prosecutors race against time and biology to bring the final perpetrators to account before death claims them first.

These late trials raise uncomfortable questions.

Is justice denied when it arrives so late? Can a centenarian in a wheelchair, their crimes committed in youth, meaningfully face accountability?

And perhaps most troubling: why did it take so long?

–

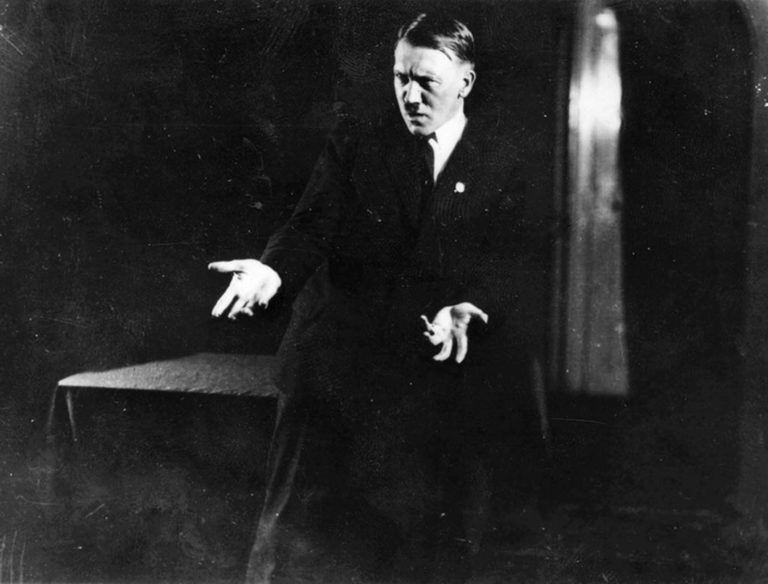

Hitler On Trial - The Beer Hall Putsch

“The lenient sentence was a catastrophe for Germany and a personal triumph for Hitler. He had turned a trial for high treason into a propaganda platform.”

Ian Kershaw, historian

The Nazi movement’s relationship with the legal system began not with its triumph, but with its failure.

On the evening of November 8th 1923, Adolf Hitler burst into Munich’s Bürgerbräukeller beer hall, fired a shot into the ceiling, and declared that the national revolution had begun. Within twenty-four hours, his attempted putsch lay in ruins, sixteen Nazis dead, and Hitler himself fleeing to a supporter’s house where he would be arrested two days later.

The Beer Hall Putsch should have ended Hitler’s political career.

He stood accused of high treason—a crime that traditionally carried the death penalty in Germany.

Instead, his trial became a propaganda triumph that transformed him from a regional agitator into a national figure.

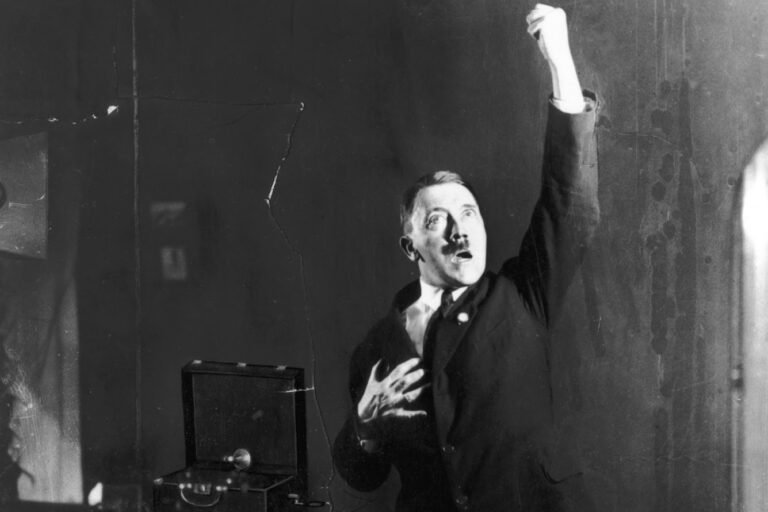

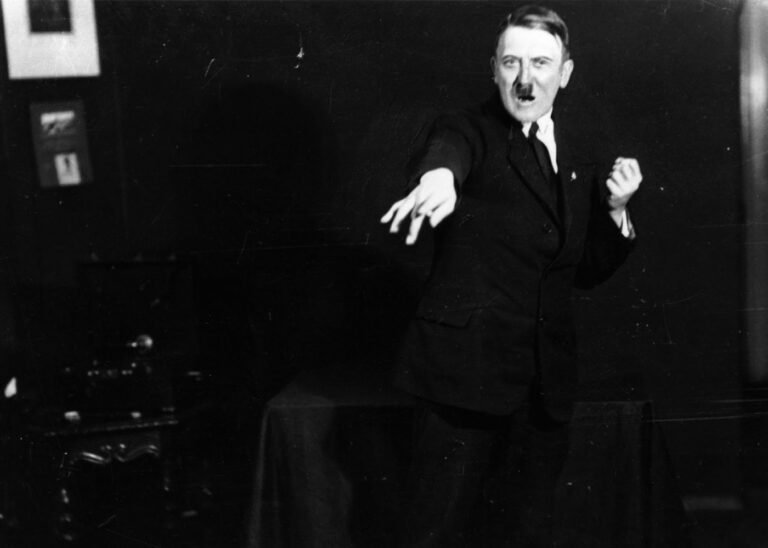

The trial, which began in February 1924, was presided over by Judge Georg Neithardt, a conservative magistrate known for leniency toward right-wing defendants who claimed patriotic motives. Hitler wore his Iron Cross throughout the proceedings, awarded for bravery during the First World War, and turned the courtroom into a platform for his political ideology. Rather than defending his actions, he attacked the Weimar Republic itself, blamed Germany’s defeat on Jews and Marxists, and proclaimed that the “Eternal Court of History” would acquit him.

The judges gave him what he wanted.

Found guilty of high treason, Hitler received the minimum sentence of five years in Landsberg Prison – and a remarkably comfortable imprisonment at that.

Festungshaft, or fortress detention, was reserved for those deemed to have acted from honourable if misguided motives. Hitler was allowed visitors almost daily, received fan mail from admirers, and spent his time dictating his manifesto ‘Mein Kampf’ to compatriot Rudolf Hess.

He served less than nine months before his pardon and release on December 20th 1924.

This leniency proved catastrophic.

Not only did it provide Hitler with with the kind of martyrdom he sought – a demonstration of his conviction to his cause, albeit one without much great suffering – but also allowed Hitler time to refine his political strategy.

He emerged convinced that power must be achieved through legal means, using the democratic system against itself. He would enter through the ballot box and undermine democracy from within rather than battering down doors.

The original sin of German jurisprudence – the failure to fully hold the Nazi movement legally accountable for armed insurrection – directly enabled Hitler’s rise to power.

It was a lesson the Nazi Party never forgot.

When they finally achieved power, they would ensure that the legal system conclusively obliterated their enemies without a hint of leniency.

–

Nazi Legal Practice - Judge, Jury, and Executioner

“The political leadership, not the law, determines right and wrong.”

Otto Georg Thierack, Minister of Justice for the Third Reich

The Nazi seizure of control over the German legal profession stands as one of the most chilling aspects of their consolidation of power.

Within months of Hitler becoming Chancellor in January 1933, the judiciary and legal profession underwent a transformation that would provide the framework for and enable twelve years of state-sanctioned criminality.

The Civil Service Law of April 1933 removed Jewish judges, prosecutors, and lawyers from their positions. The German Lawyers’ Association was dissolved and replaced with the National Socialist Lawyers’ League. Judges who showed insufficient enthusiasm for Nazi ideology found themselves transferred, demoted, or dismissed. Those who remained understood what was expected of them.

The result was a legal system that became an instrument of terror rather than justice.

The People’s Court (Volksgerichtshof), established in 1934, handled political cases with predetermined outcomes. Its president, Roland Freisler, screamed abuse at defendants, denied them adequate representation, and handed down death sentences with assembly-line efficiency. Between 1934 and 1945, the People’s Court sentenced approximately 5,000 people to death.

Traditional courts were equally complicit.

German judges, many of whom had served under the Weimar Republic, adapted with remarkable speed to their new role as enforcers of Nazi racial and political policy. They handed down death sentences for “defeatism,” for listening to foreign radio broadcasts, for telling jokes about the Führer. They applied the Nuremberg Laws with meticulous precision, destroying lives and families with legal sophistry about fractional Jewish ancestry.

The military justice system was even more savage.

Nearly 40,000 death sentences were handed down by military tribunals during the war, compared to just 48 in the First World War. Desertion, which during the First World War might have resulted in imprisonment, now meant execution by firing squad. The Wehrmacht court-martialed and executed soldiers for crimes as trivial as stealing food or expressing doubts about ultimate victory.

But perhaps the most chilling aspect of Nazi legal practice was its veneer of procedure.

The regime maintained elaborate legal justifications for its crimes. The Nuremberg Laws were meticulously drafted and promulgated according to formal legislative process. Even the Holocaust operated under pseudo-legal authorization. The Wannsee Conference of January 1942, where the ‘Final Solution’ was planned, produced minutes and assigned bureaucratic responsibilities. Adolf Eichmann, the head of Jewish Affairs, and many other perpetrators would later claim they were simply following legally authorised orders.

This corruption of law would have profound implications for postwar justice.

How do you prosecute crimes that were technically legal under the regime that committed them? How do you hold accountable those who claim they were merely following orders issued by lawful authority? These questions would haunt prosecutors for decades.

The Nazis had made themselves judge, jury, and executioner.

After 1945, the world would attempt to render judgment on them—but the process would prove far more complex and incomplete than anyone imagined.

–

The Nuremberg Trials & Confrontation

“That four great nations, flushed with victory and stung with injury stay the hand of vengeance and voluntarily submit their captive enemies to the judgment of the law is one of the most significant tributes that Power has ever paid to Reason.”

Robert H. Jackson, U.S. Chief of Counsel for the prosecution of Nazi war criminals at the Nuremberg trials 1945

The question of what to do with captured Nazi leaders was just one of many topics that arose in Allied discussions.

The post-war occupation of Germany would have to be settled; with the allocation of zones and population, the questions of reparation and reconstruction answered, and the return of refugees, slave labourers, and prisoners of war be organised.

While these issues were all major – none of them carried the weight of legally reckoning with the perpetrators of crimes committed by the National Socialist regime and its minions.

For that would also show the righteousness of the war being fought in the first instance – the undeniable raison d’etre written with the blood and bones of the murdered millions.

Winston Churchill initially favored summary execution – identifying the top Nazis and shooting them.

Stalin’s show trials in the Soviet Union provided another model.

But ultimately, the Allies chose a different path: a public trial that would establish an irrefutable historical record and demonstrate the rule of law triumphing over tyranny.

The International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg opened on November 20th 1945, in the Palace of Justice, in the only major German city with a courthouse left largely intact by Allied bombing.

The city was also where the Nazi Party’s first official party congress and rally took place in 1927 – and for years afterwards.

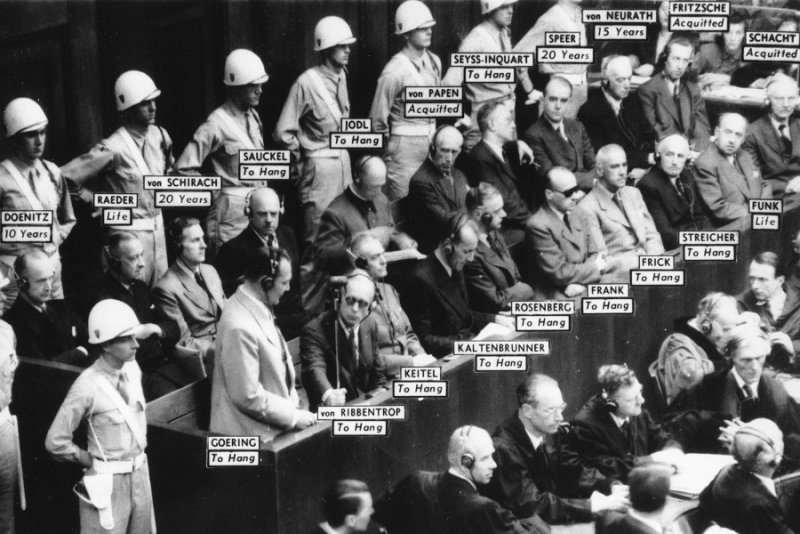

Twenty-four major Nazi leaders faced charges in Nuremberg under a novel legal framework: crimes against peace, war crimes, crimes against humanity, and conspiracy to commit these crimes.

It was the first time in history that the leaders of a defeated nation faced formal judicial proceedings rather than summary execution or exile.

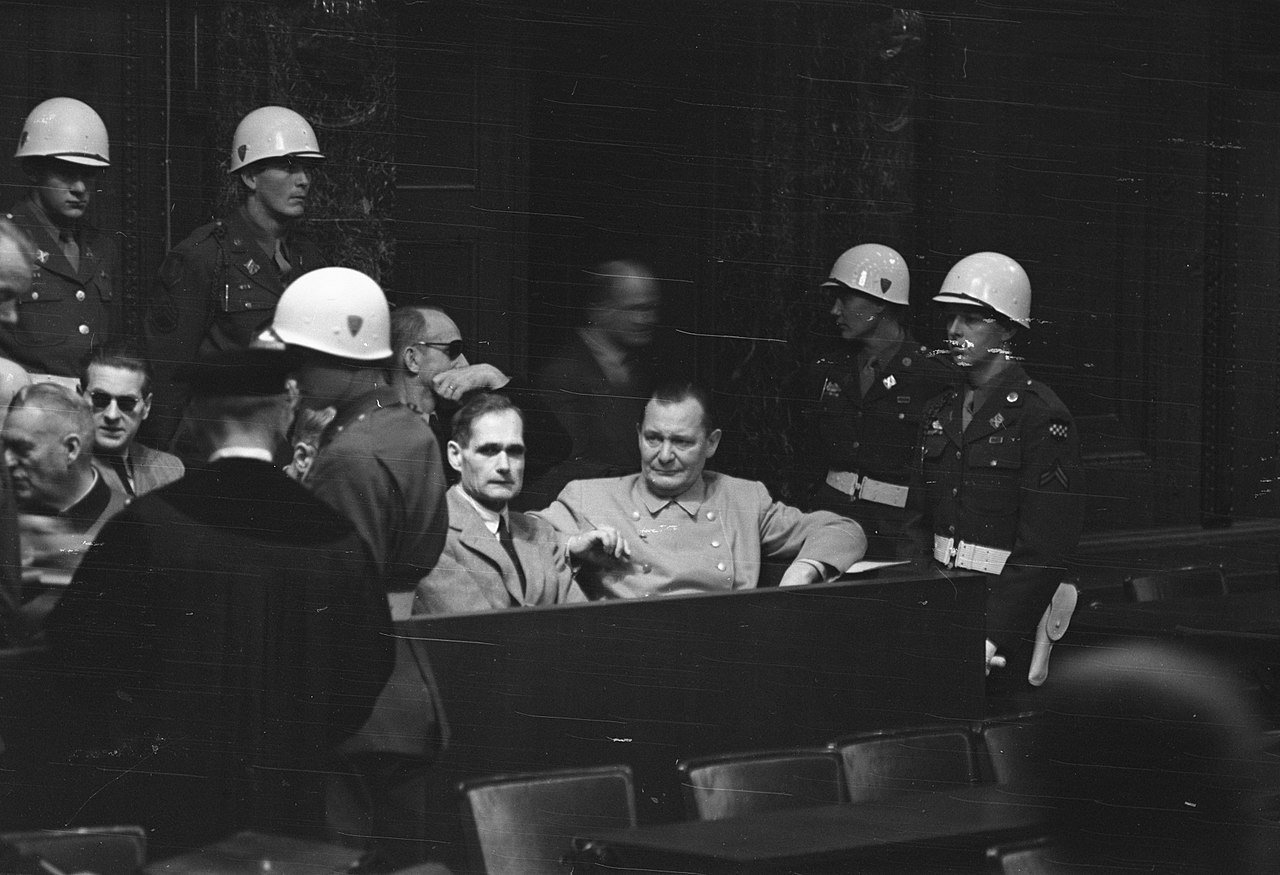

The defendants presented a grotesque parade of banality and arrogance.

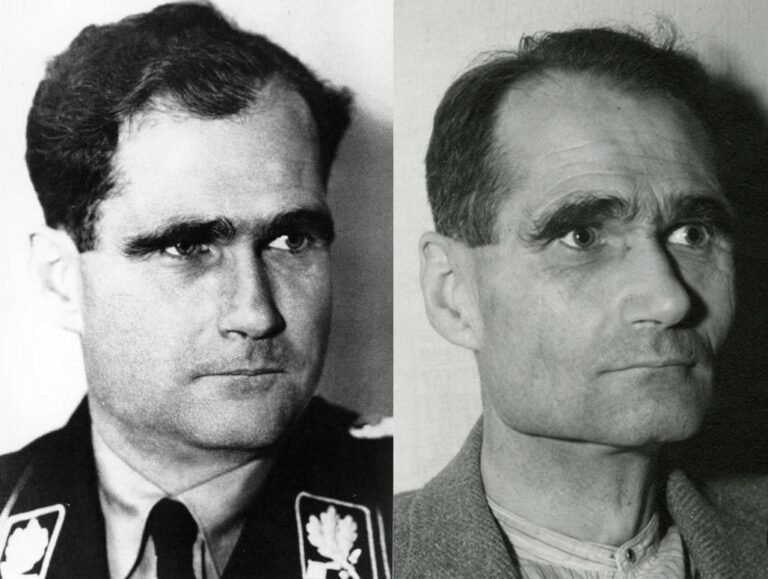

Hermann Göring, once Hitler’s designated successor, had lost weight in captivity but retained his theatrical defiance. Rudolf Hess appeared mentally unstable, claiming amnesia. Julius Streicher, the vicious publisher of Der Stürmer, maintained his antisemitic ravings even in the dock. Only Albert Speer, Hitler’s architect and armaments minister, expressed something resembling remorse – though historians would later debate its authenticity.

The trial lasted nearly a year, featured over 100,000 documents, and heard testimony from hundreds of witnesses.

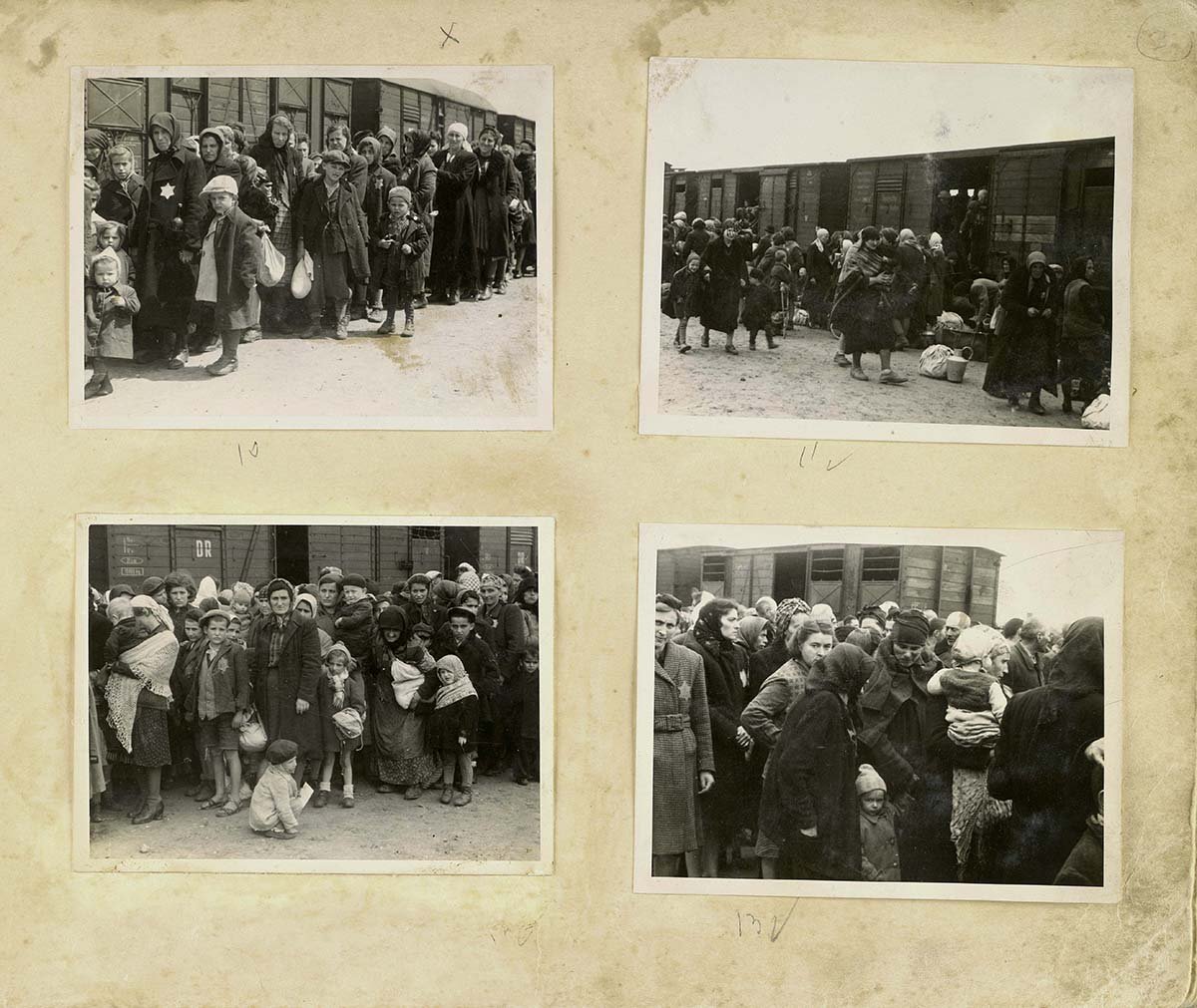

For the first time, the world confronted the full scope of Nazi atrocities through meticulous documentation: films of concentration camp liberation, orders for mass executions bearing signatures of the accused, statistics of industrial-scale murder.

The horror was overwhelming – and undeniable.

Twelve defendants received death sentences. Göring cheated the hangman by taking cyanide hours before his scheduled execution. The others were hanged on October 16th 1946.

Three received life imprisonment, four got lesser sentences, and three were acquitted.

Martin Bormann was tried and sentenced in absentia; his remains would not be discovered until 1972.

But the first Nuremberg trial of the twenty-four major faces was only the beginning.

The subsequent Nuremberg trials targeted specific groups: doctors who performed gruesome medical experiments, judges who had perverted justice, Einsatzgruppen commanders who had massacred hundreds of thousands in mobile killing operations, industrialists who had profited from slave labor.

- The Doctors’ Trial exposed Josef Mengele’s horrific experiments (though Mengele himself had escaped).

- The Justice Trial put judges and prosecutors in the dock for their role in judicial murder – including the infamous Roland Freisler, though he had died during an Allied bombing raid.

- The Einsatzgruppen Trial documented the systematic murder of over one million Jews and others through mobile killing squads that followed the Wehrmacht into the Soviet Union.

In the Soviet occupation zone, trials proceeded with less procedural rigor but equal determination.

At Pankow Town Hall in Berlin, former Sachsenhausen staff faced Soviet military tribunals in 1947. These trials received less international attention but resulted in fifteen of the sixteen defendants being sentenced to life imprisonment with hard labour (the last defendant, the Capo Karl Zander received 15 years imprisonment).

The British conducted trials in their occupation zone, including the Hamburg Ravensbrück trials that put female concentration camp guards in the dock. Twenty defendants received death sentences.

The French, too, held trials in their zone. Between 1946 and 1954, France prosecuted 2,136 individuals for war crimes, crimes against humanity, and other atrocities committed during the German occupation of France and in other territories occupied by Nazi forces.

Yet for all this activity, the majority of Nazi perpetrators escaped immediate justice.

The scale of criminality was simply too vast.

Over 200,000 individuals are estimated to have participated in Nazi crimes.

Only a fraction faced prosecution in the immediate postwar years.

Many slipped through the cracks as occupied Germany descended into administrative chaos. Others benefited from the Cold War’s emerging priorities, as both East and West Germany sought to rebuild and the Western Allies focused on containing Soviet expansion.

By the early 1950s, as Germany regained sovereignty, the window for Allied prosecution was closing.

What followed would be a long, frustrating, and often failing effort by German authorities to pursue justice for crimes most of their countrymen wanted to forget.

–

The Ones Who Got Away

“The trouble with Eichmann was precisely that so many were like him, and that the many were neither perverted nor sadistic, that they were, and still are, terribly and terrifyingly normal.”

Hannah Arendt, author of ‘Eichmann in Jerusalem’

While prosecutors assembled documents and built cases, thousands of Nazi war criminals were escaping Europe through a network of routes and sympathisers that would later be called the “ratlines.”

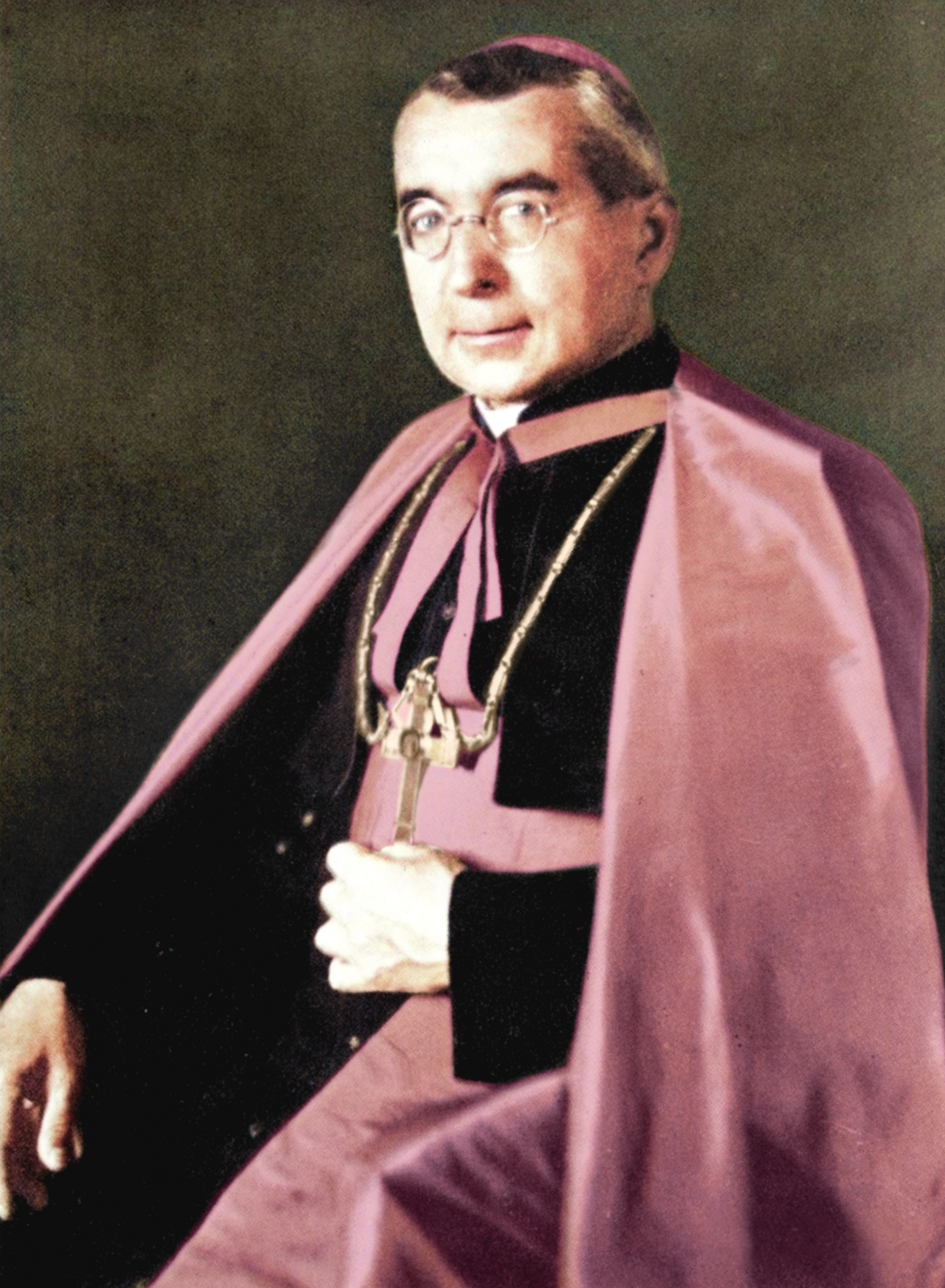

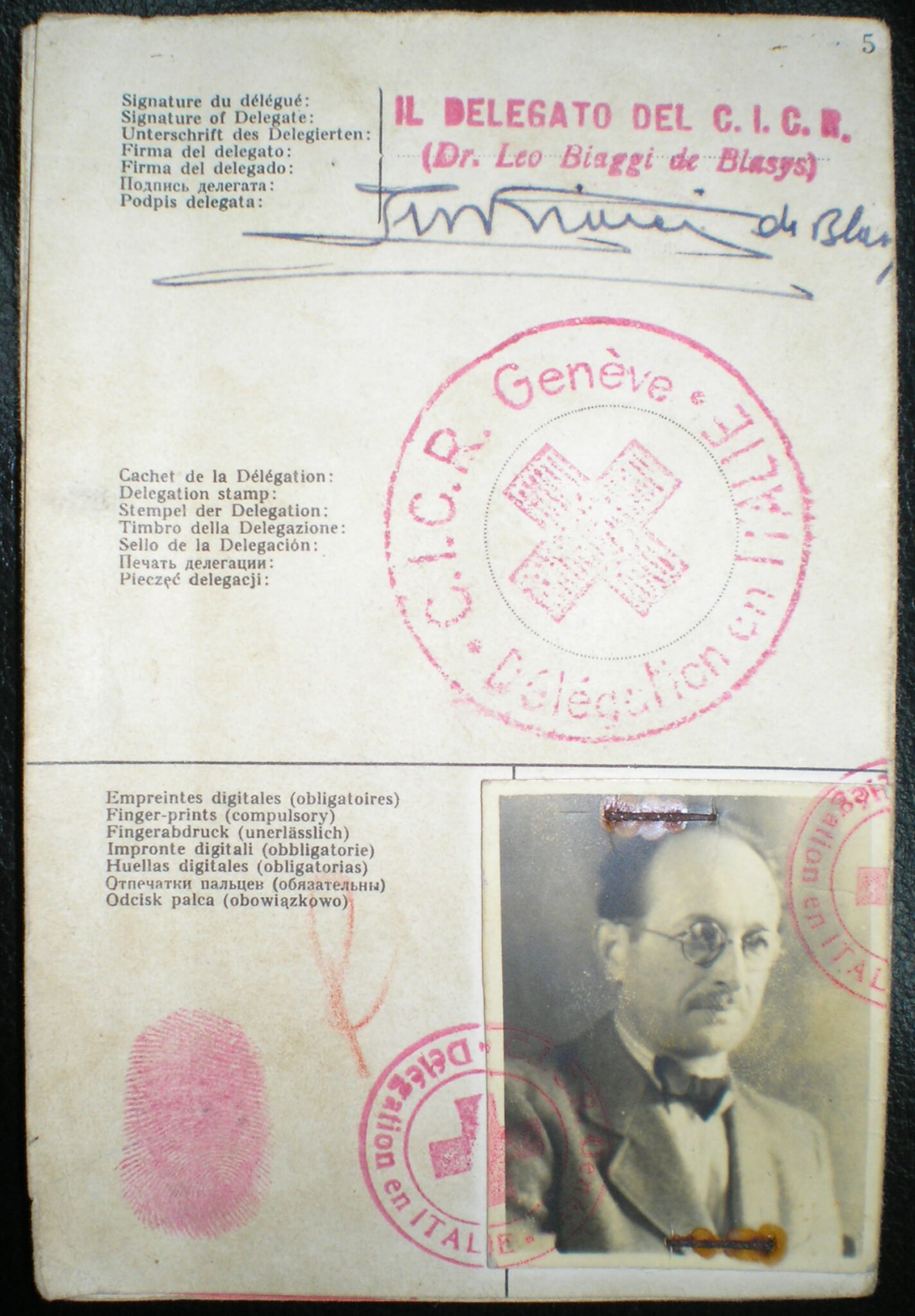

These escape networks, facilitated by elements within the Catholic Church, the International Committee of the Red Cross, and even some Western intelligence agencies, spirited high-ranking Nazis and their collaborators to safe havens in South America and the Middle East.

Adolf Eichmann, the architect of Holocaust logistics, was among them.

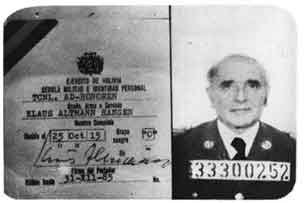

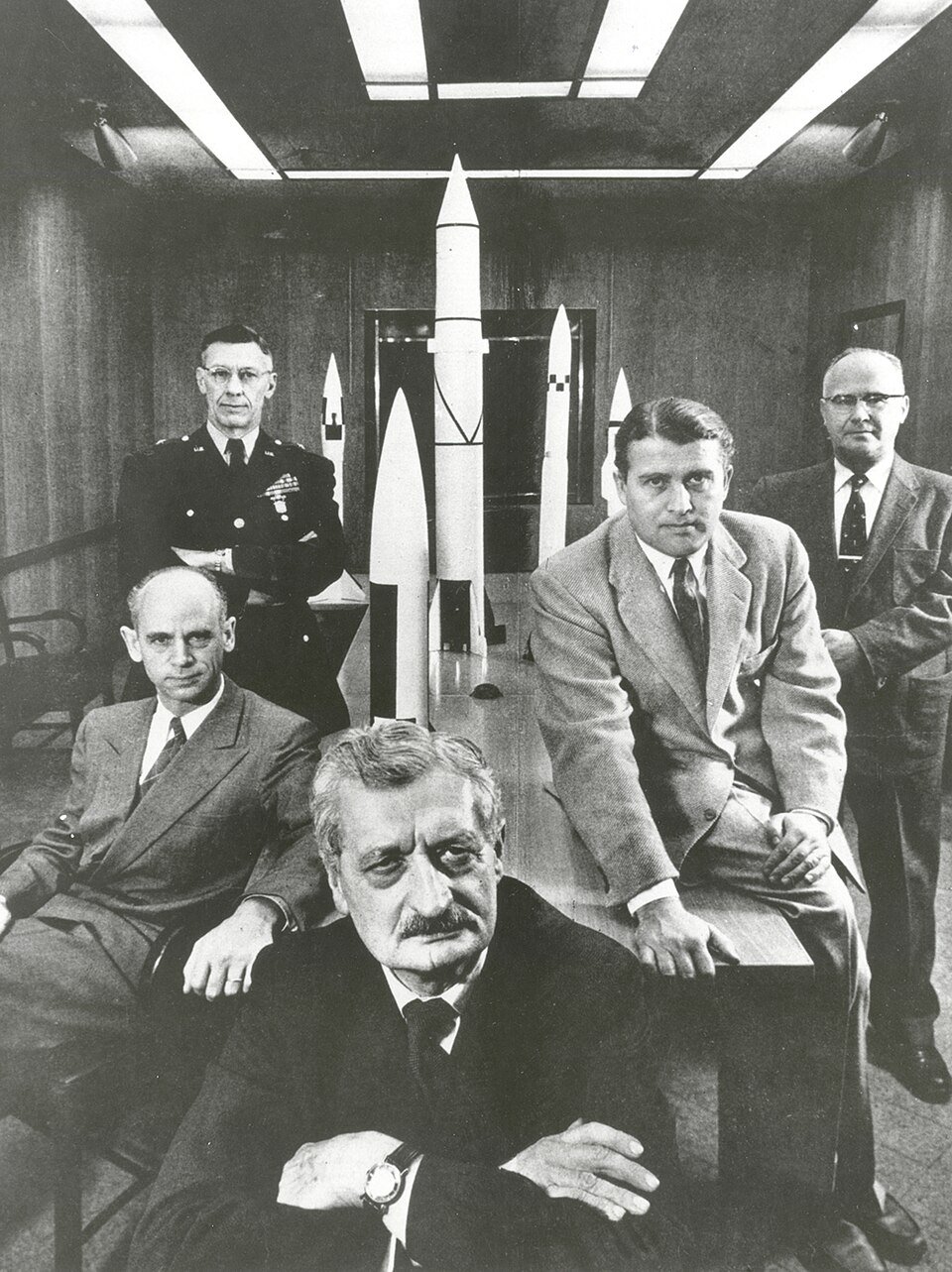

Captured by American forces in 1945, he initially hid his true identity. He escaped from detention in 1946 and spent years working on German farms under assumed names before making his way to Italy in 1950. There, with assistance from an organization directed by Catholic Bishop Alois Hudal, a Nazi sympathizer, Eichmann obtained papers identifying him as ‘Ricardo Klement’ and boarded a ship for Argentina.

He was not alone.

- Josef Mengele, the ‘Angel of Death’ of Auschwitz, followed a similar path.

- Klaus Barbie, the ‘Butcher of Lyon’, found refuge in Bolivia with American intelligence assistance, valued for his anticommunist credentials.

- Franz Stangl, commandant of Treblinka and Sobibor extermination camps, ended up in Brazil working for Volkswagen. Eichmann himself eventually found employment at Mercedes-Benz in Buenos Aires.

Argentina, Brazil, and Paraguay became particular havens. Argentina under Juan Perón openly welcomed Nazi fugitives.

Thousands arrived, some retaining their real names, others adopting new identities. They formed communities, opened businesses, and lived comfortably while survivors struggled to rebuild shattered lives.

The ratlines operated with shocking efficiency, moving Nazis from safe houses in Germany to monasteries in Italy and finally onto ships bound for South America.

The network rumoured to have enabled these escapes became known by various names: ODESSA (Organisation der ehemaligen SS-Angehörigen) being the most common, though historians debate whether this formal organisation existed or whether it was a looser network of sympathisers.

The Catholic Church’s role, in particular, remains controversial.

While Pope Pius XII’s defenders argue he acted to help genuine refugees, evidence shows that some church officials knowingly assisted war criminals. Bishop Alois Hudal in Rome was particularly active, viewing anticommunism as a greater priority than justice for Holocaust victims. His letters explicitly refer to helping fugitives escape “political persecution” by Jewish organizations and Allied authorities.

Western intelligence agencies also bear responsibility.

In the emerging Cold War, former Nazis with intelligence value or anticommunist credentials became assets.

- The Americans recruited former SS intelligence officers.

- The British did likewise.

- The Soviets captured and employed German scientists and intelligence personnel.

The desire to gain advantage over former allies outweighed concerns about past crimes.

Yet the hunters pursued them.

Simon Wiesenthal, himself a Holocaust survivor, made it his life’s work.

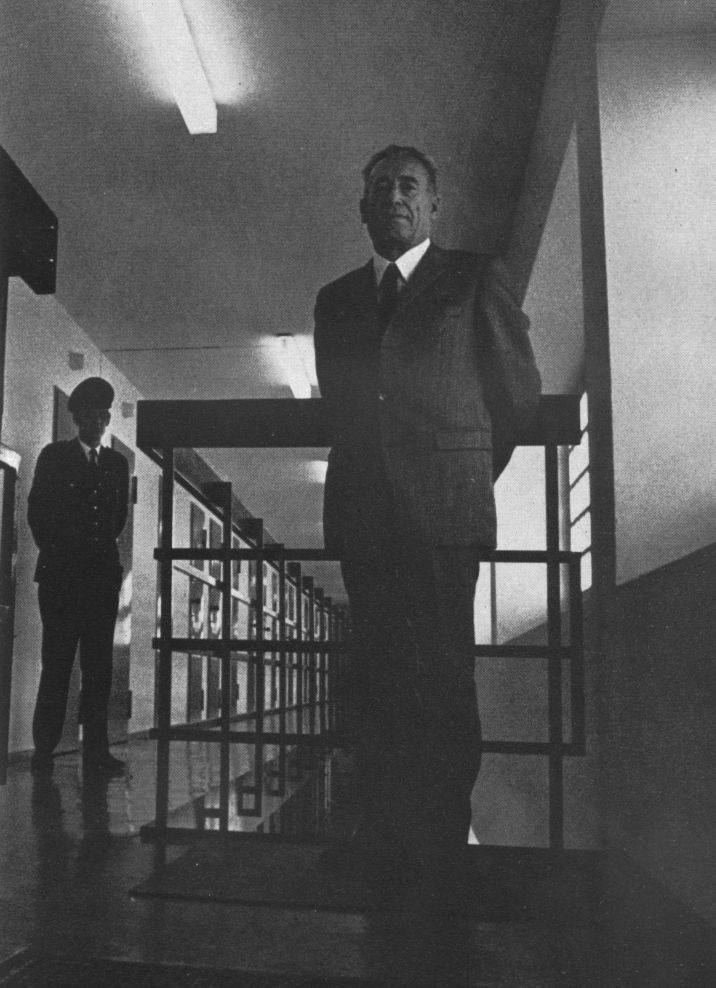

The Israeli Mossad eventually tracked Eichmann, kidnapping him from a Buenos Aires suburb on May 11th 1960. Drugged and disguised as an El Al airline crew member, Eichmann was smuggled onto an aircraft and brought to Israel.

His trial in Jerusalem in 1961 was a watershed moment.

For the first time, Holocaust survivors testified at length about their experiences. Hannah Arendt’s controversial reporting introduced the phrase “the banality of evil” to describe Eichmann’s bland bureaucratic demeanor.

He claimed he was following orders, applying administrative efficiency to a terrible task but bearing no personal malice toward his victims. The court was not persuaded. Eichmann was convicted and hanged on May 31st 1962—the only execution ever carried out by the State of Israel.

Franz Stangl was captured in Brazil in 1967 and extradited to West Germany. In conversations with author Gitta Sereny before his death in 1971, Stangl struggled to articulate how he became complicit in mass murder. His interviews reveal the psychological mechanisms of perpetrators: compartmentalisation, obedience to authority, moral disengagement from victims reduced to abstractions.

But many more were never caught.

- Mengele died in Brazil in 1979, drowning while swimming, having evaded justice for decades.

- Alois Brunner, one of Eichmann’s key deputies, lived in Syria until his death around 2010.

- Aribert Heim, the “Doctor Death” of Mauthausen, allegedly died in Cairo in 1992, though his fate remained officially unconfirmed for years.

- Christian Wirth, former commandant of three Operation Reinhard extermination camps, was killed by Yugoslav partisans in 1944, escaping postwar justice entirely.

The pattern was clear: senior perpetrators with connections and resources often escaped, while lower-level participants—those without means to flee or knowledge to hide—faced prosecution.

This created a profound injustice.

The architects of genocide often died comfortably in exile, while those who implemented their orders sometimes faced trial. Justice remained incomplete, frustratingly elusive.

–

Justice Delayed & Justice Denied

“The second guilt is the suppression of the first.”

Ralph Giordano, German journalist and survivor, on post-war German denial

The 1960s marked a crucial turning point in German confrontation with Nazi crimes.

The Frankfurt Auschwitz Trials, beginning in December 1963, represented the most comprehensive German effort to prosecute concentration camp personnel.

Twenty-two defendants, all former SS members at Auschwitz-Birkenau, faced German justice in proceedings that would last nearly two years and comprise 183 days of hearings.

The trials were initiated not by systematic government investigation but by a chance complaint.

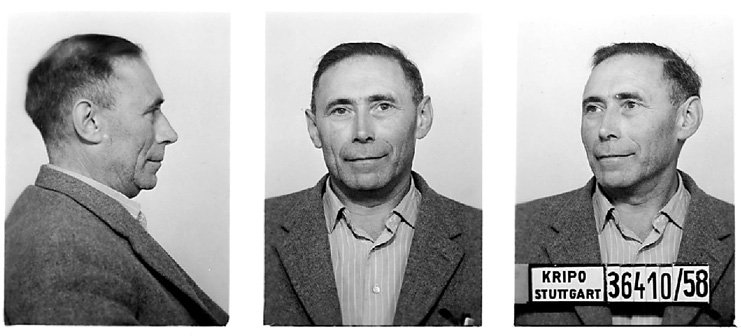

In 1958, an Auschwitz survivor reported Wilhelm Boger, former head of the camp Gestapo, to Stuttgart police. This single complaint triggered investigations that eventually revealed the identities of dozens of Auschwitz personnel living quietly in postwar Germany.

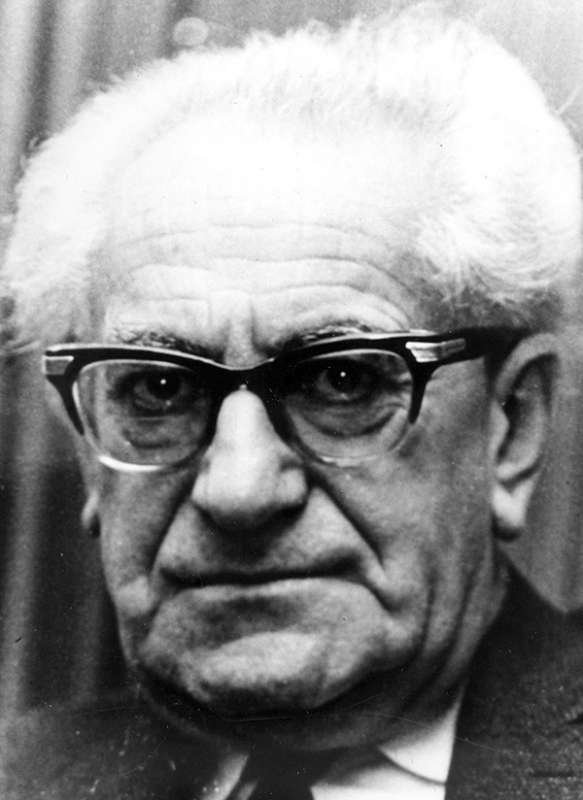

Chief prosecutor Fritz Bauer, himself a Jewish survivor who had fled Nazi persecution, drove the process forward. Bauer believed that only by confronting the truth about Auschwitz could Germany hope to move beyond its past. Yet he faced enormous resistance. Many Germans wanted to forget.

Former Nazis had integrated into postwar society—as teachers, businessmen, civil servants. The judiciary itself contained former Nazi Party members. The political will to prosecute was weak.

The Frankfurt trials brought over 360 witnesses to testify—211 survivors and 54 former SS personnel.

The testimony was devastating.

Survivors described selections, medical experiments, arbitrary beatings, systematic starvation. They identified defendants, pointing across the courtroom at men who had wielded life-and-death power twenty years earlier. Some defendants showed remorse.

Others claimed they were following orders or denied involvement despite documentary evidence.

Yet the legal outcomes were disappointing.

Under German law, prosecutors had to prove individual culpability for specific murders. Merely working at Auschwitz, facilitating its operations, or following orders to commit murder was considered a lesser crime – accessory to murder rather than murder itself.

This ‘accessory jurisprudence’ meant that perpetrators of thousands of murders received relatively light sentences.

Six defendants received life sentences, ten received shorter prison terms, and three were acquitted.

Bauer was devastated.

The media coverage, while extensive, often portrayed defendants as freakish monsters rather than ordinary Germans, allowing the public to distance themselves from collective responsibility. The trials achieved legal closure but failed to catalyze the national moral reckoning Bauer had hoped for.

Similar patterns repeated across subsequent decades.

In West Germany, the Central Office of the State Justice Administrations for the Investigation of National Socialist Crimes, established in Ludwigsburg in 1958, investigated tens of thousands of cases.

Yet only a small fraction resulted in convictions.

Witnesses had died or scattered.

Documentary evidence was incomplete.

Defendants claimed faulty memories.

Statutes of limitations threatened to end prosecutions entirely until Parliament abolished them for murder in 1979.

The Majdanek Trials in Düsseldorf, beginning in 1975, became the longest Nazi war crimes trial in history—lasting over five years and 474 sessions.

Hermine Braunsteiner-Ryan received life imprisonment.

Yet even this marathon proceeding left many feeling justice was inadequate, particularly when complications of her diabetes led to release in 1996.

The 1980s and 1990s saw prosecutions slow to a trickle. Defendants were dying of old age. Public attention shifted to new concerns.

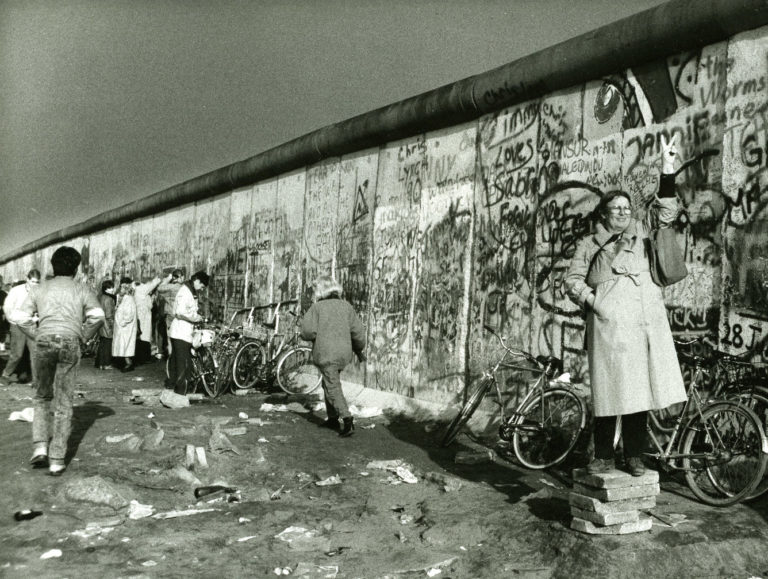

The Cold War’s end in 1989 brought reunification and new challenges.

Germany seemed ready to move on.

Then came John Demjanjuk.

–

Judging The Geriatric - The Last Nazis On Trial

“The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

William Faulkner

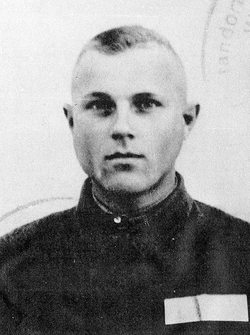

An elderly Ukrainian immigrant to the United States, John Demjanjuk had already endured one mistaken identity trial in Israel (where he was nearly executed as ‘Ivan the Terrible’ of Treblinka before that conviction was overturned).

In 2009, Germany indicted him for serving as a guard at Sobibor extermination camp. The legal theory was novel: Demjanjuk didn’t need to be proven guilty of murdering specific individuals. His mere presence at Sobibor, facilitating the camp’s operation during a period when 28,000 Jews were murdered, made him an accessory to all those deaths.

This was revolutionary.

Previously, German courts required proof of individual criminal initiative—a defendant had to have acted with ‘base motives’ or ‘excessive cruelty’ beyond merely following orders. The Demjanjuk precedent eliminated this requirement.

If you worked at an extermination camp, you were complicit in its crimes.

Demjanjuk was convicted in May 2011 and sentenced to five years in prison.

He died in 2012 with his appeal pending, meaning his conviction technically never became final under German law.

But the precedent stood.

The floodgates opened.

Oskar Gröning, the ‘Bookkeeper of Auschwitz’, was charged in 2014 and convicted in 2015 as an accessory to 300,000 murders. He had sorted money and valuables taken from arriving prisoners. He never personally killed anyone. Under the Demjanjuk precedent, it didn’t matter. He died in 2018 without serving his sentence, but his conviction was upheld on appeal, solidifying the new legal standard.

Former camp guards in their 90s and beyond began facing prosecution.

- Reinhold Hanning, convicted at 94.

- Bruno Dey, convicted at 93.

- Irmgard Furchner, a camp secretary, convicted at 97—the first woman prosecuted in decades.

- In December 2024, a German court ruled that a 100-year-old former Sachsenhausen guard could face trial despite expert testimony about his frailty.

These late prosecutions sparked debate.

Critics argued that prosecuting elderly, often infirm defendants decades after their crimes served no practical purpose. The accused were no longer dangerous. Sentences were often symbolic – suspended or never served before death. Was this justice or vengeance?

Supporters countered that justice delayed is not justice denied—it is simply justice delayed. Holocaust survivors and their descendants deserved to see perpetrators held accountable, even belatedly. The trials served important pedagogical purposes, educating new generations about the Holocaust’s reality and reinforcing that participation in genocide carries lifelong consequences.

As one survivor attorney stated, the conviction mattered more than the sentence.

Moreover, these trials established a crucial principle: there is no statute of limitations for genocide.

You cannot wait out justice.

Even at 100 years old, you may face accountability for crimes committed at 20. This principle extends beyond Nazi prosecutions. Modern war criminals in the Balkans, Rwanda, and elsewhere now know that escape to old age is not escape from justice.

The last Nazi trials also revealed how deeply ordinary people can become implicated in extraordinary evil.

These defendants were not senior officials or ideological fanatics. They were typists, guards, bookkeepers—replaceable cogs in the machinery of mass murder. Yet without them, the machinery would not have functioned.

–

Conclusion

“Like the metropolis in Faust, it has always been a rather shabby place – it is neither an ancient gem like Rome, nor an exquisite beauty like Prague, nor a geographical marvel like Rio. It was formed not by the gentle, cultured hand which made Dresden or Venice but was wrenched from the unpromising landscape by sheer hard work and determination. The city was built by its coarse inhabitants and its immigrants, and it became powerful not because of some Romantic destiny but because of its armies and its work ethic, its railroads and its belching smokestacks, its commerce and industry, and its often harsh Realpolitik.”

Alexandra Ritchie, author of Faust’s Metropolis

As of 2025, the last Nazi on trial was a 100 year old man who had served as a guard at Sachsenhausen Concentration Camp in 1943. Appearing in court in December 2024, a centenarian defendant in a wheelchair who was seventeen years old when he committed his crimes.

The journey from Hitler’s lenient treatment after the Beer Hall Putsch to today’s prosecutions of centenarian guards reveals how concepts of justice and accountability have evolved. The original sin of German jurisprudence—failing to adequately punish Nazi treason in 1924—directly enabled Hitler’s rise. That failure taught the world a bitter lesson about the cost of judicial leniency toward extremism.

The Nazi corruption of Germany’s legal system showed how law itself can become an instrument of terror. Judges, prosecutors, and lawyers who should have been guardians of justice instead became accessories to mass murder, cloaking atrocities in pseudo-legal procedure.

Nuremberg established the principle that “following orders” is no defense for crimes against humanity. The Frankfurt Auschwitz Trials confronted Germans with the truth about extermination camps. The capture of Eichmann demonstrated that fleeing to South America offered no permanent refuge. The Demjanjuk precedent eliminated the requirement to prove specific individual acts of murder.

Each step expanded the scope of accountability. Yet justice remained frustratingly incomplete. Tens of thousands of perpetrators lived out comfortable lives unpunished. Many died before facing trial.

Some trials resulted in acquittals or lenient sentences.

That the trials continue is a credit to the legal system; as the last Nazis on trial are not the last Holocaust perpetrators. They are simply the last we can reach.

Behind them stand thousands of ghosts—the Mengeles, Eichmanns, Stangls who escaped, the officials who ordered murders from comfortable offices, the industrialists who profited from slavery and death.

The historical record will judge them harshly, in ways that no earthly courts ever did.

***

If you’ve enjoyed reading this article, consider booking one of our private guided tours of Berlin.

Bibliography

Arendt, Hannah (1963). Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil. Viking Press

Bryant, Michael S. (2014). Eyewitness to Genocide: The Operation Reinhard Death Camp Trials, 1955–1966. Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press. ISBN 978-1-62190-070-2

Goñi, Uki (2002). The Real Odessa: Smuggling the Nazis to Perón’s Argentina. Granta

Kershaw, Ian (1998). Hitler: 1889–1936 Hubris. W. W. Norton & Company

Kinstler, Linda (2022). Come to this Court & Cry: How the Holocaust Ends. New York: Public Affairs Press. ISBN 978-1-54170-261-5

Klee, Ernst; Dressen, Willi; Riess, Volker, eds. (1991). “The Good Old Days” — The Holocaust as Seen by its Perpetrators and Bystanders. New York: MacMillan

Klarsfeld, Serge (ed.), The Auschwitz Album, Lilly Jacob’s Album, New-York, 1980.

Sereny, Gitta (1974). Into That Darkness: An Examination of Conscience. Vintage

HISTORICAL ARTICLES

Mythbusting Berlin

Are There Any Nazi Statues Left In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

Visitors to Berlin often arrive expecting to find the physical remnants of the tyranny of the 20th century still standing – statues of dictators, triumphal arches, or bronze idols. Instead, they often find none. The stone symbols and statues of the Third Reich are still gazing down on them, however, hiding in plain sight. But why are there no statues of Hitler? Did the Allies destroy them all in 1945, or is the truth stranger

Could The Western Allies Have Captured Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

To contemplate a Western Allied capture of Berlin in 1945 is to challenge the established endgame of the Second World War. What was the true military and logistical feasibility of a Western Allied assault on the Nazi capital? What factors truly sealed Berlin’s fate, and what might have changed had the Allies pushed eastward?

Answering these questions means delving into the complex interplay of logistics, political maneuvering, and the competing visions for a post-war world

Did Any Of The Rothschild Dynasty Die In The Holocaust? – Mythbusting Berlin

The Rothschild name is synonymous with immense wealth, influence, and persistent conspiracy theories—especially during the era of Nazi Germany. Often targeted by antisemitic propaganda, the family’s survival during World War II has sparked myths about their supposed immunity from Nazi persecution. But did any Rothschild family member actually perish in the Holocaust? This article explores that compelling question, unraveling historical misconceptions and revealing the reality behind one of Europe’s most famous dynasties.

Did Frederick The Great Introduce The Potato To Germany? – Mythbusting Berlin

One of the more bizarre claims to fame attributed to the first King of Prussia is that the man who would go down in history known as Frederick the Great introduced the potato to Germany during his reign back in the 1700s. This starchy root vegetable has undoubtedly become a staple part of German cuisine – an essential addition to any plate of Schnitzel, Schweinshaxn, and Königsberger Klopse – however, whether Frederick the Great is

Did Hitler Escape To Argentina In 1945? – Mythbusting Berlin

Although Nazi leader, Adolf Hitler, certainly remains an inescapable figure, could there be any truth to the story of his escape to Argentina in 1945? That the most wanted man on earth could simply vanish, to spend the rest of his life peacefully in South American obscurity captivates imaginations. Yet, despite numerous investigations, this tale persists primarily as myth—fueled by speculation, hearsay, and conspiracy theories.

Did Hugo Boss Design The Nazi Uniforms? – Mythbusting Berlin

The idea that Hugo Boss – the man whose name now adorns expensive suits and fragrances – was the creative genius behind the Nazi uniforms suggests a terrifying collision of haute couture and holocaust – a marriage of high style and high crimes. The image is striking: a German tailor sketching the ultimate villain’s costume. But history, as usual, is far messier, more bureaucratic, and more banal than the internet memes suggest. To understand who

Did Rudolf Hess Really Commit Suicide? – Mythbusting Berlin

On a summer’s day in 1987, the last Nazi war criminal of the Nuremberg trials was found dead in a prison built for hundreds, yet for two decades, housed only him. The official verdict was suicide, a straightforward end to a life defined by fanaticism, delusion, and contradiction.

But the simplicity of the report belied the complexity of the man and the 46 years he had spent in Allied custody. In the meticulously controlled

Did The Nazis Develop Nuclear Weapons? – Mythbusting Berlin

The Nazi obsession with super-weapons became so serious in the closing stages of the Second World that Adolf Hitler personally believed that such ‘Wunderwaffen’ both existed in a usable form – and would save the country from defeat. Had the Nazis managed to develop nuclear weapons by 1945 – the outcome of the war would surely have been different. But how close were Hitler, Himmler, and his henchmen to developing an A-bomb?

Did The Nazis Invent Decaf Coffee? – Mythbusting Berlin

Persistent rumors claim that Nazis preferred their coffee anything but pure, leading some to wonder if they might have influenced the development of decaffeinated coffee. Although decaf was already widely available across Europe by the mid-20th century, speculation continues: could the Nazis really have played a role in popularizing—or even discovering—this caffeine-free alternative, or is this simply another caffeinated conspiracy cooked up to sensationalize an ordinary historical detail?

Did The Nazis Invent The Bicycle Reflector? – Mythbusting Berlin

The fruits of wartime ingenuity are plenty – so many, in-fact, that it has become somewhat of a worn cliche that as the guns start firing the innovators get to work, often solving problems while providing more problems for the enemy to overcome.The kind of progress that results in the production of newer improved, more lethal weapons, such as to increase the chances of victory.

Did The Nazis Run The Largest Counterfeiting Operation In History? – Mythbusting Berlin

During the Second World War the Nazis masterminded an astonishing plot to destabilise Britain by flooding its economy with counterfeit banknotes. Crafted in secret by concentration camp prisoners, this forged fortune became the most ambitious counterfeiting operation ever attempted. But was it history’s largest? Dive into the extraordinary tale of Operation Bernhard,

rife with deception, survival, and intrigue—revealing the truth behind one of the Third Reich’s most audacious schemes and its surprising legacy.

Did The Second World War End In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

When is a war ever truly over? When the last shot is fired in anger would seem like the best measure. Rarely, though, is it possible to gain insight into such a moment.

Remarkably, a record still exists of such a moment at the end of the First World War on the Western Front. A seismic register and recording of the last belching battery of British guns firing artillery across no-man’s-land, followed by a profound

Did The Spanish Flu Pandemic Help The Nazis Take Power? – Mythbusting Berlin

The devastating Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918-1919 struck amid Germany’s post-war turmoil, compounding social instability, economic hardship, and widespread political disillusionment. Could this catastrophic health crisis have indirectly paved the way for Nazi ascension? While often overshadowed by war and revolution, the pandemic’s profound psychological and societal impacts arguably contributed to the perfect storm, enabling extremist ideologies—including Nazism—to gain popularity and ultimately seize power in a fractured Germany.

Have Adolf Hitler’s Remains Been DNA Tested? – Mythbusting Berlin

In the smouldering ruins of Berlin in 1945, the world’s most wanted man vanished. Did Adolf Hitler, as official history attests, die by his own hand in the Führerbunker? Or did he escape, fuelling a thousand conspiracy theories that have echoed for decades? For years, the Soviets claimed to hold the gruesome proof of his death: a skull fragment and a set of teeth, locked away in Moscow archives. But in an age of definitive

How Did The Nazi Concentration Camps Differ From The Soviet GULAG?

The Nazi concentration camps and Soviet Gulag system have often been conflated in popular imagination—twin symbols of twentieth-century totalitarian horror. Yet the two systems operated on fundamentally different principles. One extracted labor to fuel industrialisation while accepting mass death as collateral damage; the other evolved into purpose-built machinery of genocide. Understanding these distinctions isn’t merely academic—it reveals how different ideologies produce different atrocities, and why Germany and Russia reckon with these legacies so differently today.

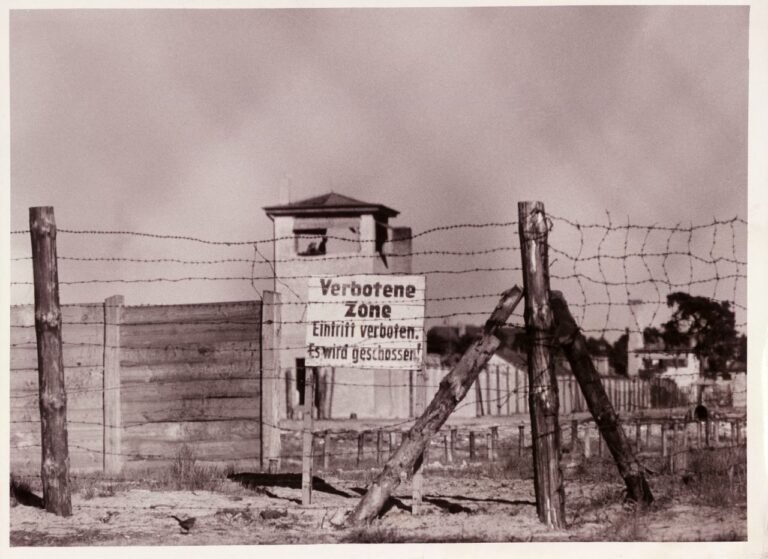

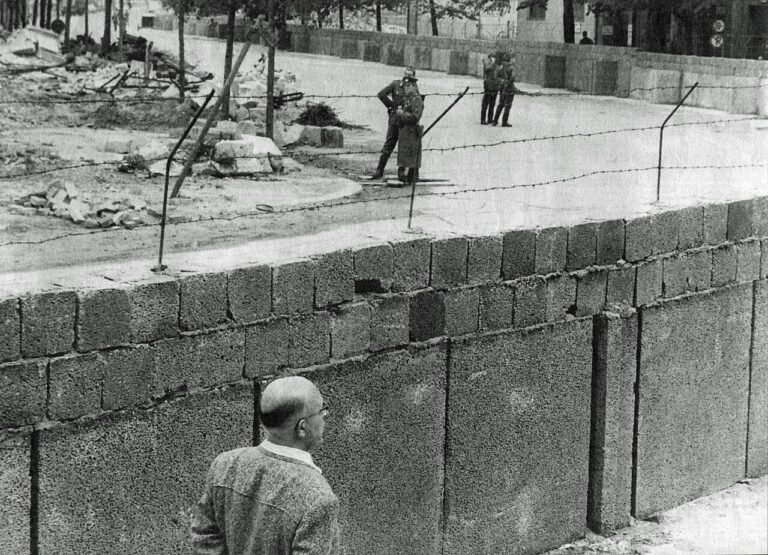

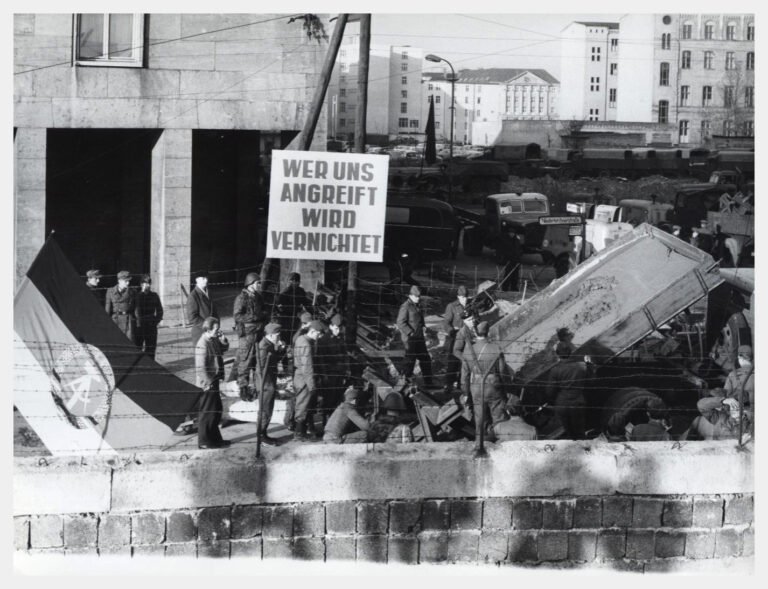

How Long Did It Take To Build The Berlin Wall? – Mythbusting Berlin

It is one of the most enduring images of the 20th century: a city divided overnight. The popular narrative tells us that Berliners went to sleep in a unified city and woke up in a prison. While the shock of August 13th 1961, was very real, the idea that the ‘Wall’ appeared instantly is a historical illusion. The physical scar that bisected Berlin was not a static creation, but a living, malevolent beast that evolved

How Many Assassination Attempts On Adolf Hitler Were There? – Mythbusting Berlin

Nazi leader, Adolf Hitler, projected an aura of invincibility, a man of destiny shielded by providence. But behind the carefully constructed image of the untouchable Führer lies a story of constant threat, of bombs that failed to detonate, and errant bullets that missed their mark. Unearth the hidden history of the numerous attempts on Hitler’s life as we explore the courage of those who tried to change the course of history and the devil’s luck

How Many Jews Died In The Holocaust? – Mythbusting Berlin

The answer to the question posed of how many Jews died in the Holocaust is a simple one: too many. That merely one death was an unforgivable obscenity is a fundamental and necessary realisation in understanding the capriciousness of this unparalleled racial genocide. To comprehend, however, the full number of Jews murdered in Europe by the Nazi regime in the 1930s and 1940s is a detective story of epic proportions: the evidence overwhelming, multifaceted, and

How Many People Died Trying To Escape East Germany? – Mythbusting Berlin

The image of the Berlin Wall is seared into our collective memory, a concrete symbol of Cold War oppression. We think of the daring escapes and the tragic deaths of those who failed. But that well-known number is only a fraction of the truth. The story of those who died trying to escape East Germany is far broader and more complex than most imagine, stretching along a thousand-kilometer border and out into the cold waters

How Old Is Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

A relatively new arrival in Europe, Berlin is over 1000 years younger than London, nevermind Rome or Athens, Jerusalem or Jericho. Just how old is Berlin though?

A question fraught with false assumptions and distortions – that has more often than not been answered with propaganda as it has with the cold hard truth.

Was Adolf Hitler A Drug Addict? – Mythbusting Berlin

Solving the enigma of the ‘Führer’ has become a preoccupation for many, since the arrival of the Austrian-German onto the world stage – although moving beyond the mythology without falling into the trap of prejudically extrapolating on the psychopathography of Hitler or demonising so as to excuse his actions has proven problematic. What to make of the man who became more than the sum of his masks? The painter; the military dilettante, the mass murderer,

Was Adolf Hitler A Freemason? – Mythbusting Berlin

History abhors a vacuum, but adores a mystery. Such is the speculative fiction suggesting a secret allegiance behind the rise of the Third Reich – that the catastrophe of the Second World War was orchestrated from the shadows of a Masonic lodge. The image of Adolf Hitler—the drifter from Vienna turned dictator—as a covert initiate of the very brotherhood he publicly reviled, however, creates a paradox that collapses under scrutiny. As when we unlock the

Was Adolf Hitler Gay? – Mythbusting Berlin

In the shadowy corridors of Third Reich history, few questions provoke as much tabloid curiosity and scholarly exasperation as the sexuality of Adolf Hitler. For decades, rumors have swirled—whispered by political enemies in 1930s Munich, psychoanalyzed by American spies in the 1940s, and sensationalized by revisionist authors today. Was the dictator who condemned thousands of men to concentration camps for “deviant” behavior hiding a secret of his own? By peeling back the layers of propaganda,

Was Adolf Hitler Jewish? – Mythbusting Berlin

Was the dictator who orchestrated the murder of millions of European Jews secretly one of them? It is perhaps the darkest irony imaginable, a story whispered for decades in backrooms, bars, and conspiracy forums alike. The most-common rumour – the ‘Frankenberger Myth’ – suggests that Adolf Hitler’s paternal grandfather was Jewish, a secret so damaging it could have unraveled the entire Nazi regime. But where does this claim come from? And, more importantly, is there

Was Currywurst Invented In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

Explore the story behind what many consider Berlin’s most iconic snack—the ever-so-humble Currywurst. Often hailed as an enduring symbol of culinary creativity amid Cold War scarcity, this humble dish has inspired fierce debate about its true origin. But was it genuinely invented here in Berlin, or have proud locals simply adopted and elevated this spicy street-food favorite into legendary status all their own?

Was Fanta Invented By The Nazis? – Mythbusting Berlin

As one of the most secretive organisations in the world, the Coca Cola corporation refuses to share its secret recipe with anyone. Famously insisting only on shipping the base syrup of its drinks to plants around the world to be carbonated and distributed.

This combined with the trade limitations of the Second World War may have led to the introduction of one of the most popular soft-drinks in the world. But could it be true:

Was Frederick The Great Gay? – Mythbusting Berlin

Frederick II of Prussia, better known as Frederick the Great, is often remembered as the archetypal enlightened monarch – a brilliant military commander, patron of the arts, and learned philosopher. Yet behind the stern portraits of this 18th-century warrior-king lies a personal life long shrouded in intrigue and speculation. Intrigue around the king’s sexual orientation has persisted through the centuries, chiefly revolving around one question: Was Frederick the Great gay?

Was Henry Ford A Nazi? – Mythbusting Berlin

US auto tycoon, Henry Ford, holds the ignominious distinction of being the only American Adolf Hitler praised by name in his National Socialist manifesto: ‘Mein Kampf’. This was not, as it turns out, the only connection between Ford and the Party of Hitler, Himmler, and the Holocaust.

Ford’s overt affinity with the Third Reich reveals a troubling past. How deep these connections ran, and how consequential they were for both sides, is a chapter

Was The Colour Blue Invented In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

Tracing the true history of blue—from ancient Egyptian dyes to the accidental discovery of Prussian Blue in a Berlin lab. We’ll debunk myths about seeing blue, explore colonial indigo plantations, scale mountains with a cyanometer, and trace Van Gogh’s starry skies—all to answer one question: how did Berlin shape our understanding of the world’s rarest color?

Was The Döner Kebab Invented In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

Unlikely icon of immigrant success; fast food symbol of the working class; over-hyped midnight disco eat; or culturally appropriated cuisine? Its influence goes far beyond layers of seasoned meat and fresh vegetables stuffed into pita bread. But does Berlin deserve credit as the Döner Kebab’s true birthplace, or has the city merely refined and popularized a culinary tradition imported from elsewhere?

Was The Fall Of The Berlin Wall An Accident? – Mythbusting Berlin

On a seasonally crisp night in November 1989, one of the most astonishing events of the 20th century occurred. After twenty eight years, three months, and twenty eight days of defining and dividing the German capital, the Berlin Wall ceased to exist – at least in an abstract sense. Although the removal of this symbol of the failure of the East German system would take some time, its purpose – as a border fortification erected

Was The Nazi Party Democratically Elected? – Mythbusting Berlin

The myth persists that Adolf Hitler rose to power through popular democratic choice. Yet history reveals a darker, more complicated truth. Hitler’s ascent involved exploiting democratic institutions, orchestrating violence, propaganda, and political intrigue—not a simple election victory. Understanding how Germany’s democracy collapsed into dictatorship helps illuminate the dangerous interplay between public desperation, elite miscalculations, and extremist ambition, providing crucial lessons for safeguarding democracy today.

Were The Allied Bombings Of Germany War Crimes? – Mythbusting Berlin

The history of the Allied bombing of Germany during the Second World War still triggers fierce debate. Was reducing cities to rubble a necessary evil – justice from above in a just war – or an unforgivable crime? Can the intentional targeting of civilians ever be justified as militarily necessary?

In a conflict where all rules seemed to vanish, an even more pertinent question persists: by the very standards they would use to judge their

Were The Nazi Medical Experiments Useful? – Mythbusting Berlin

Before the Nazi period, German medicine was considered the envy of the world – a shining monument to progress. But deep within that monument, a rot was spreading, one which would collapse the entire structure into an abattoir. From the wreckage, we are left with a profoundly uncomfortable inheritance: a moral enigma wrapped in doctor’s whites.

What to make of the data, the images, and the terrible knowledge gleaned from unimaginable human suffering. Whether

What Are The Origins Of The Nazi Salute? – Mythbusting Berlin

A specter is haunting the modern mind, a gesture so charged with the dark electricity of history that its mere depiction can unleash a storm of controversy.

It is a simple movement: the right arm, stiff and straight, raised to the sky. But in that simplicity lies a terrifying power, a symbol of a regime that plunged the world into an abyss and a chilling reminder of humanity’s capacity for organised hatred.

This

What Are The Origins Of The Nazi Swastika? – Mythbusting Berlin

Long before the legions of the Third Reich marched beneath its stark, unnerving geometry, the swastika lived a thousand different lives. It was a symbol of breathtaking antiquity, a globetrotting emblem of hope and good fortune that found a home in the most disparate of cultures. To even begin to understand its dark 20th-century incarnation, one must first journey back, not centuries, but millennia.

What Are The Pink Pipes In Berlin? – Mythbusting Berlin

A first-time visitor to Berlin could be forgiven for thinking the city is in the midst of a bizarre art installation. Bright pink pipes, thick as an elephant’s leg, climb out of the ground, snake over pavements, arch across roads, and disappear back into the earth. Are they part of a complex gas network? A postmodern artistic statement? A whimsical navigation system? These theories, all logical, are all wrong. The truth is far more elemental,

What Do The Colours Of The German Flag Symbolise? – Mythbusting Berlin

What does a flag mean? Is it merely a coloured cloth, or does it hold the hopes, struggles, and identity of a nation? The German flag, with its bold stripes of black, red, and gold, is instantly recognisable. But the story of its colours is a tumultuous journey through revolution, suppression, and reinvention. The common explanation for their symbolism is a simple, romantic verse, yet the truth is a far more complex and contested tale,

What Happened To Adolf Hitler’s Alligator? – Mythbusting Berlin

It is often said that you can tell a lot about a person by their relationship with animals; that owners often come to look and behave like their pets. Or is it perhaps more that people choose their pets to correspond to their personality? Nazi leader Adolf Hitler’s love of dogs, for example, is well documented but what is there to make of his relationship with reptiles?

What Happenened To The German Royal Family? – Mythbusting Berlin

When the smoke cleared over the trenches in November 1918, the German Empire had evaporated, and with it, the divine right of the Hohenzollern dynasty. Conventional wisdom suggests the family simply vanished into the sepia-toned obscurity of history books—exiled, forgotten, and irrelevant. But dynasties, like weeds in a landscaped garden, are notoriously difficult to uproot entirely. The story of the German royals did not end with the Kaiser’s flight to Holland; it merely shifted gears.

What Is The Difference Between Fascism & Nazism? – Mythbusting Berlin

While the terms ‘Fascist’ and ‘Nazi’ are often bandied around interchangeably as shorthand for tyranny – Italian fascism and German National Socialism were distinctly different beasts. Albeit ideological kin. One an ideology of state-worship, born from post-war chaos and national pride; the other built upon a fanatical, pseudo-scientific obsession with race. Two peas in the same totalitarian pod – twins in tyranny – more succinctly summarised as the Nazi chicken to the Fascist egg.

What Was Checkpoint Charlie? – Mythbusting Berlin

Checkpoint Charlie remains among Berlin’s most visited historical sites, famed worldwide for its significance during the Cold War. Originally established as a modest border-crossing point, it evolved dramatically over the decades into an international symbol of freedom, espionage, and intrigue. Today, critics and locals often dismiss it as little more than a tourist trap—Berlin’s Disneyland—but how exactly did Checkpoint Charlie get its peculiar name, and what truths hide behind its popularity?

What Was Prussia? – Mythbusting Berlin

Prussia’s legacy is both remarkable and contentious—once a minor duchy, it rose dramatically to shape modern European history. Renowned for military discipline, administrative efficiency, and cultural sophistication, Prussia was instrumental in uniting the German states, laying foundations for a unified Germany. But how did this kingdom, with its roots in Baltic territories, achieve such prominence, and why does its complex history continue to evoke admiration, debate, and occasional discomfort in Germany today?

What Was The Berlin Airlift? – Mythbusting Berlin

In the ruins of 1948, the silence of Berlin was not a sign of peace, but a held breath before a new catastrophe. The city, drowning in rubble and political intrigue, became the staging ground for the twentieth century’s most audacious gamble. While popular history remembers the chocolate parachutes and smiling pilots, the reality of the Berlin Airlift was a terrifying operational nightmare born from a ruthless currency war. It wasn’t just a humanitarian mission;

What Was The Socialist Kiss? – Mythbusting Berlin

It is one of the most curious and enduring images of the Cold War: two middle-aged, grey-suited men, locked in a fervent embrace, their lips pressed together in a kiss of apparent revolutionary passion. This was the ‘Socialist Fraternal Kiss’, a ritual that, for a time, seemed to encapsulate the unwavering solidarity of the Eastern Bloc.

But what was behind this seemingly intimate gesture? Was it a genuine expression of camaraderie, a piece of

Who Built The Berlin Wall? – Mythbusting Berlin

One of the most common questions I have encountered from people curious about Berlin, and often so cryptically phrased. Who built the Berlin Wall? A simple five-word query, yet one that can be read one of two ways. More than thirty years since the ‘Fall of the Wall’, the story of its construction continues to baffle many who are mainly familiar with its existence through knowledge of its importance…

Who Really Raised The Soviet Flag On The Reichstag? – Mythbusting Berlin

One iconic photograph has come to symbolise the Red Army’s victory over Nazi Germany in 1945—the Soviet flag waving triumphantly above Berlin’s battered Reichstag building. Yet behind this enduring image lies controversy, confusion, and political manipulation. Who truly raised the Soviet banner atop the Reichstag? Was it a spontaneous act of heroism or carefully staged Soviet propaganda? Decades later, unraveling the truth reveals surprising layers beneath the mythologized symbol of Soviet triumph.

Who Was Really Responsible For The Reichstag Fire? – Mythbusting Berlin

Various theories have been posited as to who actually set fire to the German parliament in 1933. Was it the opening act in an attempted Communist coup or a calculated false flag operation carried out by elements of the Nazi Party, intended to create the conditions necessary for introducing single-party rule? And what part did the young man from Holland, arrested shirtless inside the building the night of the fire, play in this event?

Who Were The Last Nazis On Trial? – Mythbusting Berlin

More than eighty years after the Holocaust, courtrooms across Germany still echo with testimony from the final chapter of Nazi justice. Centenarian defendants in wheelchairs, their faces hidden behind folders, arrive to answer for crimes committed in their youth. These are not the architects of genocide—those men faced their reckoning at Nuremberg decades ago. These are the guards, the secretaries, the bookkeepers: ordinary people who enabled extraordinary evil. Their trials represent a legal revolution: the

Why Is Berlin The Capital Of Germany? – Mythbusting Berlin

There was little in its humble origins—as a twin trading outpost on a minor European river—to suggest that Berlin was destined for greatness. It sits on the flat expanse of the North European Plain, a landscape once dismissively referred to as the “sandbox of the Holy Roman Empire.” Unlike other world capitals, it lacks breathtaking scenery or a naturally defensible position. It is a city built not on majestic hills or a grand harbour, but