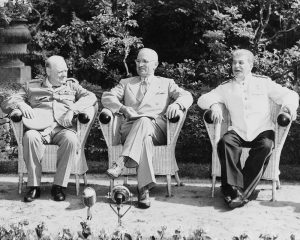

The Potsdam Conference was the second time in a matter of just under a few decades that the leaders of a victorious coalition faced the problem of what to do with a defeated Germany and a postwar Europe.

The men of 1945 knew perfectly well how poorly the previous generation had handled this same problem, so there was a shared sense of commitment in trying to avoid making similar mistakes this time around, no matter how much tension could be felt on several issues during the seventeen days at Potsdam. Now, in a matter of hours, the loose ends on the final agreements would hopefully be tied, the wording for the protocol finalized, and farewells between the delegations exchanged.

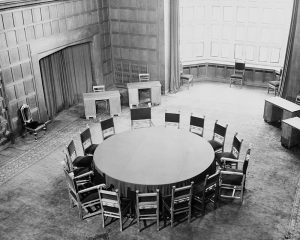

Packing had already been going on at the ‘Little White House’ for several days and everyone, especially President Truman, was extremely ready to leave. So at 3:30PM the President wasted no time calling the twelfth plenary session to order at Cecilienhof.

The first item on the agenda was agreeing on the wording when it came to the drafting committee on the protocol on German reparations. Although significant progress on the matter had been made yesterday when the Big Three agreed on extracting reparations from the occupation zones and on the Soviet Union’s acquisition of industrial equipment from the Western Zones, Secretary Jimmy Byrnes raised the question on the Soviet’s claim to gold and German external assets. Both the American and British delegations felt that – in return for the capital equipment allocated to the Soviets – German external assets should be included as a source of reparations for countries other than Russia and Poland.

“The question which must be made clear is what it is meant by the western zones,” Stalin immediately declared. “The Soviet Union agrees not to claim anything from the western zones.”

“The zones occupied by America, Britain, and France are the western zones,” Truman said.

“We don’t claim gold. As to shares in foreign investments everything west of the military demarcation line is relinquished by us. Everything east of the line should go to us,” Stalin asserted.

During its years of occupation in parts of central and Eastern Europe, Nazi Germany had – often through transfers made under duress or by use of outright force – acquired large interests and substantial control in foreign economies including various oil fields, shipping, industrial plants, and so forth. There was a lot of wealth to be distributed and the American and British delegations knew that those who fell victim to the Nazis would make their claim for these outside assets.

“We are supposed to settle with Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia in regard to their reparations claim. These countries will, of course, claim German assets within their jurisdiction,” Truman reminded the other delegations.

“Yugoslavia, Czechoslovakia and western Austria are in your zone,” Stalin reminded Truman.

After Truman acknowledged Stalin’s reminder, Stalin then enquired on whether this agreement should go into the protocol and be defined by the wording of ‘respective assets’. Byrnes felt it should for the sake of making it clear that other countries who suffered under the yolk of the Nazis for – in some cases – many years and therefore could be compensated with Nazi Germany’s former external assets.

–

Before the end of WWII and even during the course of the Potsdam Conference, the Foreign Ministers had laid the groundwork for the establishment of the Allied Control Council (ACC). Seated in the American Sector in Berlin, this body would be the chief authority in Germany and coordinate Allied policy for the control of Germany. It functioned based on the instructions from the leaders of the four occupying powers on matters involving each Allied country’s own zone of occupation and matters affecting Germany as a whole.

The ACC communicated with the German people via official pronouncements such as laws, orders, directives, and proclamations – and thus would play a pivotal role in the governing of Germany and Berlin in the immediate years following WWII.

If there was one place that needed assistance the most at this time, it was Berlin. The more than three hundred and sixty devastating Allied air raids on the city, coupled with twelve days of ferocious man-to-man combat during the Battle of Berlin, left its people homeless, hungry, and living in utter ruin. If the American and British aim was to build a democratic Germany that would be prosperous and use its future economic power to pursue civilian goals and thus no longer pose a threat to anyone, something needed to be done immediately to bring relief to the devastated area that the leaders who attended the Potsdam Conference had seen firsthand.

This understanding was best articulated by Secretary of War Henry Stimson when he commented on some of the harsh proposals for the postwar period:

“…keeping Germany near the margin of hunger as a means of punishment for past misdeeds….I have felt that this was a grave mistake. Punish her war criminals in full measure. Deprive her permanently of her weapons, her General Staff and perhaps even her entire army. Guard her governmental actions until the Nazi-educated generation has passed from the stage – admittedly a long job – but do not deprive her of the means of building up ultimately a contended Germany interested in following non-militaristic methods of civilization.”

As a result of his years of volunteer work and living in London’s impoverished East End, Prime Minister Attlee also acknowledged that keeping the Germans near the margin of hunger was a grave mistake. He understood that the best way to get the wheels in motion for the time being – in order to bring some kind of initial relief to the beleaguered Berliners – was to lean on the newly established ACC for assistance. He spoke up at today’s plenary session and said:

“We have an agreement regarding the feeding and fueling of Berlin for the next 30 days. I suggest that we instruct the ACC to provide a program to provide uniform subsistence standards for the next six months. This is a practical matter which requires immediate action.”

The Soviets, on the other hand, felt completely different on the immediate use of the ACC for this kind of matter, particularly Stalin:

“That is a new question. It has not been studied. I do not think it will be possible in the near future to have a high standard of life in Germany. We must first ask the Control Council how they will provide for Berlin needs. We can not come to any decision now.”

After a bit of debate on the topic pursued, Attlee’s Foreign Minister, Bevin, stepped in and proposed to postpone the matter, realizing that Stalin was not prepared to make a humanitarian decision that directly and positively affected the enemy who his armies had just defeated. This highlights the fact that the Soviets saw matters much differently. They insisted that the Germans should at the very least not live any better than the people they had victimized; in other words, they might as well remain exactly at the margin of hunger that Stimson had decried. A Soviet diplomatic paper at Potsdam called only for the German people to have enough food to:

“Subsist without external assistance. Domestic consumption and exports,” the paper argued, should be “proportionally reduced in order to prioritize the payment of reparations.”

All along, the Soviets regarded a strong, democratically united, and economically prosperous Germany as a threat to its national security and the best way to keep it defeated was to squash any kind of collective effort in providing the most essential items and resources for its short term survival.

The Allied Control Council would be responsible for essentially all facets of German society including taking on the task of carrying out the provisions on the prosecution of German war criminals.

–

The issues of war criminals provided one of the most important tests between justice and common humanity at the Potsdam Conference. Punishing too many Germans threatened to make the occupation unpopular in German eyes and also to remove many people of talent from Germany at a time when the Allies needed their expertise.

Yet, on the other hand, to put too few people on trial meant allowing many people with blood on their hands to walk free.

The British favored a lenient approach, both to minimize the risks of the occupation and to lay a foundation for the future of Anglo-German cooperation. Anthony Eden drafted a note for Churchill at the beginning of the Conference that contained only ten names for prosecution: Luftwaffe commander Hermann Göring; Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop; former Deputy Führer Rudolf Hess, who had been in British custody since his bizarre flight to Scotland in 1941; Robert Ley, who headed the Deutsche Arbeitsfront, Germany’s only labor union during the Third Reich; Wilhelm Frick, the chief author of the Nuremberg Laws; Wilhelm Keitel, Hitler’s senior military advisor; Nazi ideologue Alfred Rosenberg; SS leader Ernst Kaltenbrunner; propagandist Julius Streicher; and Hans Frank, the Nazi Governor of Poland.

The notion that just ten men, in addition to the already deceased Adolf Hitler and Joseph Göbbels, had caused so much death and destruction made no sense, but it indeed served a political imperative.

The Soviets thought the list was far too short and demanded much more thorough purging of the Nazi system. They argued that the British had violated the spirit of the agreements already in place that called for much wider punishments for Nazi officials.

In October 1943, Stalin, Churchill, and Roosevelt had all agreed to the Moscow Declaration, which pledged that the Allies would punish and hold accountable those responsible for wartime atrocities. The agreement, like so many of its kind, said nothing about the final numbers of war criminals to be prosecuted, or about legal procedure, but the Russians clearly thought in terms of a much broader system of war crimes trials.

Yesterday’s plenary session ended in a stalemate when it came to reaching an agreement on officially naming the defendants for prosecution. The American and British representatives thought that this should be left up to the prosecutors. When the topic came up today, Stalin immediately lashed out:

“Names are necessary and are very important to give proper orientation. The people should know that we are going to try some industrialists, that is why we mentioned Krupp.”

Truman, on the other hand, did not agree: “If you name some, others will think they have escaped.”

“Well, people wonder about Hess living comfortably in England,” Stalin fired back.

Attlee quickly spoke up and said, “You need not worry about that.”

Hess presented a critical litmus test. In May 1941, he had flown from Germany to Scotland, apparently without permission from Hitler, as part of an effort to foster peace between the Germans and the British. He hoped to enlist British help in the coming German war with the Soviet Union. The British immediately questioned his mental stability and placed him under psychiatric observation.

For having proposed a joint Anglo-German war against the Soviets, Stalin wanted the British to transfer Hess to Russian custody. At one point during the Conference, Stalin repeated his demand and even offered to pay Hess’s ‘British hotel bills’ in order to speed up his transfer; this comment, of course, was a jab at what Stalin viewed as Britain’s inexcusably lenient treatment of Hess.

At any rate, the Big Three agreed that the first ten principal defendants to be tried will be named within thirty days with United States Supreme Court Justice Robert Jackson leading the prosecution.

In the end, twenty-two defendants would be charged with four main charges:

Frist: That the Nazis had conspired criminally to seize power in Germany.

Second: That Nazi Germany had planned, prepared, initiated, and waged wars of aggression, in violation of foreign treaties.

Third: That the Nazis had committed war crimes in the countries and territories occupied by the German armed forces – murder and ill-treatment of civilian populations, deportations for slave labor, killing of prisoners of war and hostages, wanton destruction of cities, towns, and villages, and the conscription of civilian labor.

Fourth: Crimes against humanity – murder, extermination, enslavement, deportation, and persecution on political, racial, and religious grounds.

Twelve of the twenty-two defendants were sentenced to death, a further seven received prison sentences, and three were acquitted. Numerous other trials against further Nazi conspirators would take place separately in the four zones of occupation in the immediate years to come.

The delegations would now have just under five hours to finalize all the agreements in the protocol and to cram in any extra details or content before the Big Three took their seats in the Cecilienhof Palace for the last time.

**

Our Related Tours

To learn more about Potsdam and visit the site of the Potsdam Conference, have a look at our Glory Of Prussia tours.

To learn more about the history of Cold War Berlin and life behind the Iron Curtain; have a look at our Republic Of Fear tours.

Bibliography

Byrnes, James (1947). Speaking Frankly. New York: Harper & Brothers. ISBN 978-0-837-17480-8

Cullough, David (1992). Truman. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-86920-5

Fabian, Nadine. “Ein Besuch in der Stalin-Villa in Potsdam.” Märkische Allgemeine. 23 August 2017, https://www.maz-online.de/Lokales/Potsdam/Ein-Besuch-in-der-Stalin-Villa-in-Potsdam

Neiberg, Michael (2015). Potsdam: The End of World War II and the Remaking of Europe. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-07525-6

McBaime, Albert (2017). The Accidental President. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0-544-61734-6

Miscamble, Wilson D (1978). Anthony Eden and the Truman-Molotov Conversations, April 1945

Roberts, Geoffrey (2007). Stalin at the Tehran, Yalta, and Potsdam Conferences

Smyser, William (1999). From Yalta To Berlin: The Cold War Struggle Over Germany. New York: St. Martin’s Press. ISBN 0-312-06605-8

Sternberg, Jan. “Churchill und die lila Plüschmöbel.” Märkische Allgemeine. 13 July 2015, https://www.maz-online.de/Thema/Specials/P/Potsdamer-Konferenz/Villa-Urbig-am-Griebnitzsee.

Truman, Harry S. (1956). Memoirs: Year of Decisions Volume 1. New York: Doubleday.