An avid early riser his whole life, President Truman sat down at his desk early in the morning on the bank of his lakeside house on lake Griebnitzsee and composed a letter to his beloved wife, Bess.

“Dear Bess,

The first session was yesterday. It had made presiding over the Senate seem tame. The boys say I gave them an earful. I hope so…I was so scared. I didn’t know whether things were going according to Hoyle (protocol) or not. Anyway, a start has been made and I’ve gotten what I came for – Stalin goes to war August 15 with no strings on it…I’ll say that we’ll end the war a year sooner now, and think of the kids who won’t be killed! That is the important thing…Wish you and Margie were here. But it is a forlorn place and would only make you sad.”

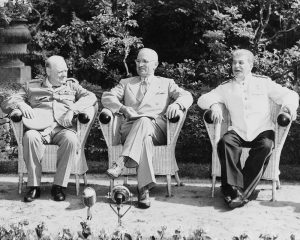

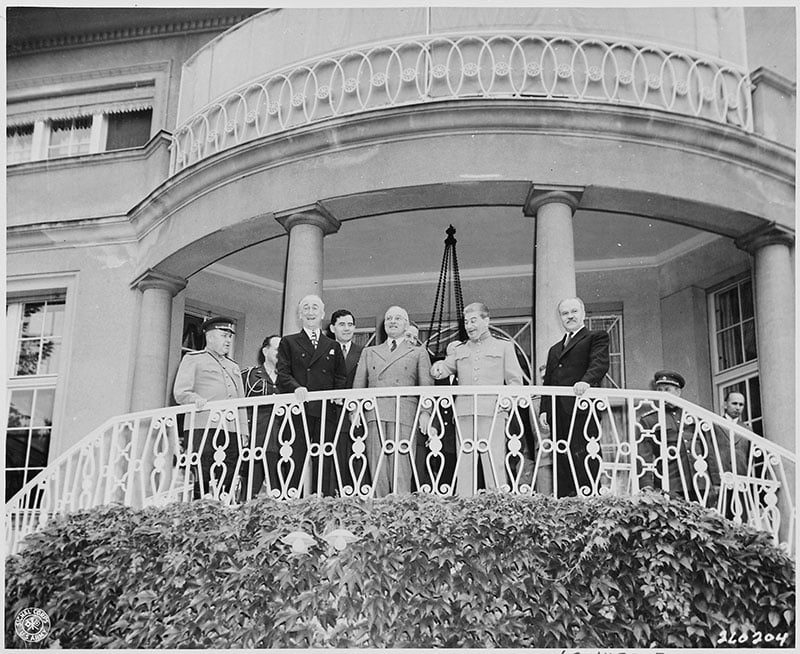

This was a big deal for President Truman and for the reputation of American foreign policy with a new leader at the helm. On the previous afternoon, he had sat down at a table with two of the most colossal figures of the 20th century – “Mr. Great Britain and Mr. Russia” as he referred to Churchill and Stalin, respectively – to begin putting together an official agenda that would determine the fate of the postwar world. It was his first formal meeting outside of Washington and his first official interaction with world leaders abroad. He appeared to be anything but “scared”, as he believed he had been. On the contrary, Truman was cool, composed, “businesslike”, as Anthony Eden described, and demonstrated radiant authority.

–

Since all three delegations and the ‘Big Three’ were essentially staying in the same neighborhood at Babelsberg – and given the fact that most of the plenary sessions were not called to order until late in the afternoon – off-the-record meetings, conversations, and lunches were a common component of the Potsdam Conference.

They provided the three leaders with the opportunity to discuss pertinent issues, freely express their opinions on official matters, give their judgements on the course of official business at future plenary sessions, and strengthen personal relationships. The latter was extremely important to Truman with regards to his newly acquired relationship with Churchill. He was well aware of the bond and affection that had been deeply felt between the Prime Minister and Roosevelt, and so Truman was somewhat compelled to try and achieve a similar status.

So shortly after 1:00pm and being accompanied by half a dozen officials, President Truman walked up to Ringstraße 23 (today Virchowstraße) to Churchill’s villa to have a private lunch with the British Prime Minister.

Whereas Truman’s performance at yesterday’s first plenary session had been widely praised, Churchill’s had been harshly criticized – even his own foreign minister, Anthony Eden, described it as “pathetic”. He looked tired, bothered, and rambled way too much.

Churchill invited the President to have a seat and immediately seemed to bring some of yesterday’s gloom to today’s lunch. He began to moan and complain about the melancholy state of Great Britain, with its staggering debt and declining influence in the world. After initially being taken aback by Churchill’s pessimistic tone, Truman tried to lift the Prime Minister’s spirits when he told him that the United States owed Britain much for having “held the fort” at the beginning of the war.

“If you had gone down like France,” Truman told Churchill, “we might be fighting the Germans on the American coast at the present time.”

The President showed the Prime Minister two telegrams that had arrived from Washington the night before confirming that the atomic bomb was essentially ready, even though Truman still had not received an exact description of the July 16th test. He told Churchill that he believed that Stalin should be informed, but was not exactly sure how to do it. Should the information come in the form of a letter, or through conversation? Churchill agreed that Stalin should be informed, but made it clear that he did not need to know any of the particulars.

Even though the United States was in possession of the atomic bomb and given the fact that it would ultimately be Truman’s decision to deploy it, it was also partly up to Churchill when it came to making the decision to inform the Soviets.

According to the Quebec Agreement that was signed between the United Kingdom and the United States in August 1943, it stipulated that the British and the Americans would combine their resources to develop nuclear weapons, and that neither country would use them against the other, or against other countries without mutual consent, or pass information about them to other countries.

In the end, Churchill thought that the information should be relayed sooner rather than later, and Truman decided that the best time to tell Stalin would be to just simply wait for the right moment during one of the forthcoming plenary sessions.

They continued to talk about the war in the Pacific and Churchill pondered whether new wording might be devised so that the Japanese could surrender but salvage some sense of its military honor.

Since 1943 the Allies had demanded an unconditional surrender and that particularly implied that Japan’s imperial government – namely the emperor – would be terminated. Understanding that this might make it more difficult to get Japan to accept unconditional surrender, Truman – and even Roosevelt – had been encouraged to add an explicit provision that stated that the imperial system and emperor could remain.

Truman countered by saying that he did not believe Japan had any military honor, especially after their surprise and deliberate attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941. As far as he was concerned, the Japanese had fractured all prior restraints on the use of its firepower, terror and aggression against the United States and its allies, and therefore, they were now simply receiving the whirlwind they had reaped.

“At any rate, they had something for which they were ready to face certain death in very large numbers, and this might not be so important to us as it was to them,” Churchill responded.

After saying this, Truman turned “quite sympathetic,” as Churchill recounted, and began talking of “the terrible responsibilities upon him in regard to unlimited effusion of American blood.”

“He invited personal friendship and comradeship,” Churchill wrote of Truman. “He seems like a man of exceptional character.”

The two men may have been very different when it came to their backgrounds and personal interests, but they were quickly forming a special bond and a personal relationship, something that was essential to ensuring a lasting cooperation in future world affairs.

–

Truman then made his way to Kaiserstraße 27 (today Karl-Marx-Straße) to pay a return visit to Stalin with his Secretary of State, Jimmy Byrnes, and his interpreter, Chip Bohlen. The three men were taken by surprise when they walked into Stalin’s villa and saw a second lunch waiting for them. Again, the Soviets painstakingly overdid themselves by preparing an elaborate meal in President Truman’s honor.

Stalin immediately informed Truman that Naotake Sato, Japan’s ambassador to the Soviet Union, had sent a message to explore the possibilities of using the Russians as intermediaries for negotiating peace. The two countries had a friendly relationship at this time, which went back to April 1941 when Japan and the Soviet Union signed a neutrality pact after France had fallen and after Germany and its allies continued to expand through Europe.

The Soviets felt that they needed to mend their diplomatic relations in the far east (the two countries had fought bitterly over Manchuria in the 1930s) for the sake of protecting their eastern border, and Japan – who was at an endless war with China – wanted to improve its international standing and secure its northern border from a possible Soviet invasion.

Stalin showed Truman Sato’s message which made a great impression on Truman. He saw it as a sign that the Russians might be ready to deal openly with the American delegation.

The President would later write:

“He (Stalin) said he wanted to cooperate with the U.S. in peace as we had cooperated in war but it would be harder. Said he was grossly misunderstood in the U.S. and I was misunderstood in Russia. I told him that we each could remedy that situation in our home countries and that I intended to try with all I had to do my part at home. He gave me a most cordial smile and said he would do as much in Russia.”

–

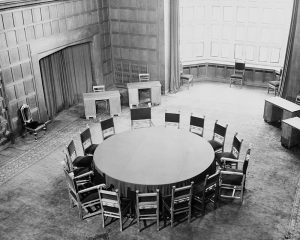

The second plenary session was called to order at 4:20pm that afternoon. Many observers agreed that Churchill once again did not seem himself. He was tired, cranky and most likely distracted by the current election count which could end his term in office in a matter of a few days.

He began the session by complaining on the record about the amount of journalists that seemed to be everywhere and stated that the work that the Big Three were doing could only be done in secrecy. He suggested that either he, Truman or Stalin go out and speak to them about the important need for secrecy during the summit. A discombobulated Molotov asked Churchill where they were and if he knew what their demands were, while an impatient and annoyed Truman interrupted and said,

“We each have a press representative here. Let them handle it. We will make no communication until the end of the Conference. I am not disturbed by them. Most of them are Americans. Your election is over and so is mine. Let us proceed.”

Truman informed the delegations that the foreign secretaries had recommended today’s topics for discussion. The formal business was to be mostly about Germany – namely, the principles for the control of it, as well as its postwar borders with Poland.

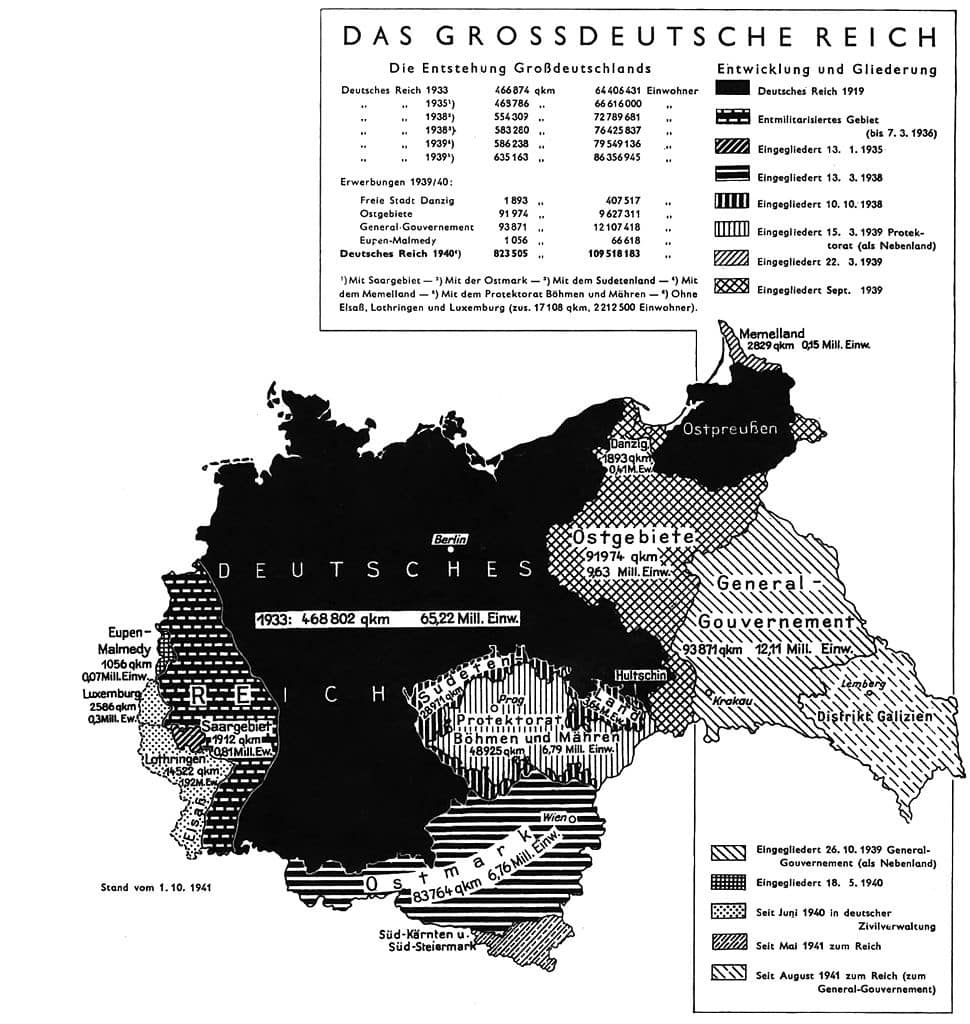

At Yalta, Stalin, Roosevelt and Churchill had agreed that a line drawn after World War I would be Poland’s eastern border with the Soviet Union once Nazi Germany had been defeated. However, the three three leaders had also decided that Poland should be compensated with ‘substantial’ German territory to its west. Stalin felt that Poland essentially deserved all of Germany east of the Oder River and Neisse River, forcing millions of Germans westward and depriving Germany of some of its richest farmland.

Churchill immediately spoke up and insisted that the delegations must agree on defining what was meant by ‘Germany’.

If they were to define Germany before WWII, then he was ready to discuss – alluding to the fact that Germany’s eastern boundaries were currently being determined by the position of the Soviet Red Army’s occupying forces.

But as far as Stalin was concerned, this was a fait accompli, while Truman refused to consider the matter settled:

Stalin: “Germany is what has become of her after the war. No other Germany exists…”

Truman: “Why not say the Germany of 1937?”

Stalin: “Minus what she has lost. Let us for the time being regard Germany as a geographical section.”

Truman: “But what geographical section?”

Stalin: “We cannot get away from the results of the war.”

Truman: “But we must have a starting point.”

After Stalin pointed out that Germany was already broken up into four occupation zones anyway, it was difficult for him to define its frontier.

Yet, Truman urged that a starting point must be defined for the sake of future decision making.

Stalin finally agreed to proceed with the ‘Germany of 1937’ as the starting point, bringing a shed of light to the delegations that a major step forward had been taken.

Finally, they turned to the question of Poland and began talks about its postwar future.

After yesterday’s first plenary session, Churchill’s Foreign Secretary, Anthony Eden, had written that Churchill was “wooly and verbose.” Again, on day two, Churchill entered into another narrative as he talked about the future of Poland. The Soviets felt that all relations with the former Polish government should be severed and that its assets be transferred to the government of national unity. This forced Churchill to talk even longer than usual, as he felt that all of this was a likely burden that would rest on Britain since it was in possession of Polish assets and since it had been financing Poland for the past five years.

After his long-winded speech, an irritated Truman concisely gave his reaction by stating that he believed that there did not seem to be any fundamental differences. He, like the British government, remained interested in the Polish government, particularly that the free elections assured by the Yalta agreement played out. Stalin also concisely stated that it was his understanding that the three governments were in favor of a unified policy.

According to biographer David McCullough, Truman was exasperated. He could ‘deal’ with Stalin, as he said, but Churchill was another matter.

Later that night he sat down at his desk and let out his frustrations with a pen:

‘I’m not going to stay around this terrible place all summer and just listen to speeches. I’ll go home to the Senate for that!’

**

Our Related Tours

To learn more about Potsdam and visit the site of the Potsdam Conference, have a look at our Royal Potsdam tours.

To learn more about the history of Cold War Berlin and life behind the Iron Curtain; have a look at our Republic Of Fear tours.

Bibliography

Byrnes, James (1947). Speaking Frankly. New York: Harper & Brothers. ISBN 978-0-837-17480-8

Cullough, David (1992). Truman. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-86920-5

Fabian, Nadine. “Ein Besuch in der Stalin-Villa in Potsdam.” Märkische Allgemeine. 23 August 2017, https://www.maz-online.de/Lokales/Potsdam/Ein-Besuch-in-der-Stalin-Villa-in-Potsdam

Neiberg, Michael (2015). Potsdam: The End of World War II and the Remaking of Europe. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-07525-6

McBaime, Albert (2017). The Accidental President. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0-544-61734-6

Miscamble, Wilson D (1978). Anthony Eden and the Truman-Molotov Conversations, April 1945

Roberts, Geoffrey (2007). Stalin at the Tehran, Yalta, and Potsdam Conferences

Smyser, William (1999). From Yalta To Berlin: The Cold War Struggle Over Germany. New York: St. Martin’s Press. ISBN 0-312-06605-8

Sternberg, Jan. “Churchill und die lila Plüschmöbel.” Märkische Allgemeine. 13 July 2015, https://www.maz-online.de/Thema/Specials/P/Potsdamer-Konferenz/Villa-Urbig-am-Griebnitzsee.

Truman, Harry S. (1956). Memoirs: Year of Decisions Volume 1. New York: Doubleday.