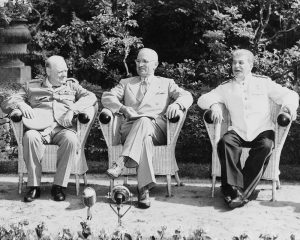

The United States Secretary of War Henry Stimson paid a call on Churchill yesterday afternoon with the intent of sharing Groves’ latest report with him.

Unfortunately, his visit abruptly ended not long after he arrived when the British delegation suddenly realized that they were going to be late for the fifth plenary session. They may have met sooner, but Churchill and other members of the delegation had just spent most of the day in Berlin for a British victory parade on the same street where Adolf Hitler’s troops had held their own victory parade almost five years earlier – on 27 July 1940 – following the defeat of Poland and the surrender of France.

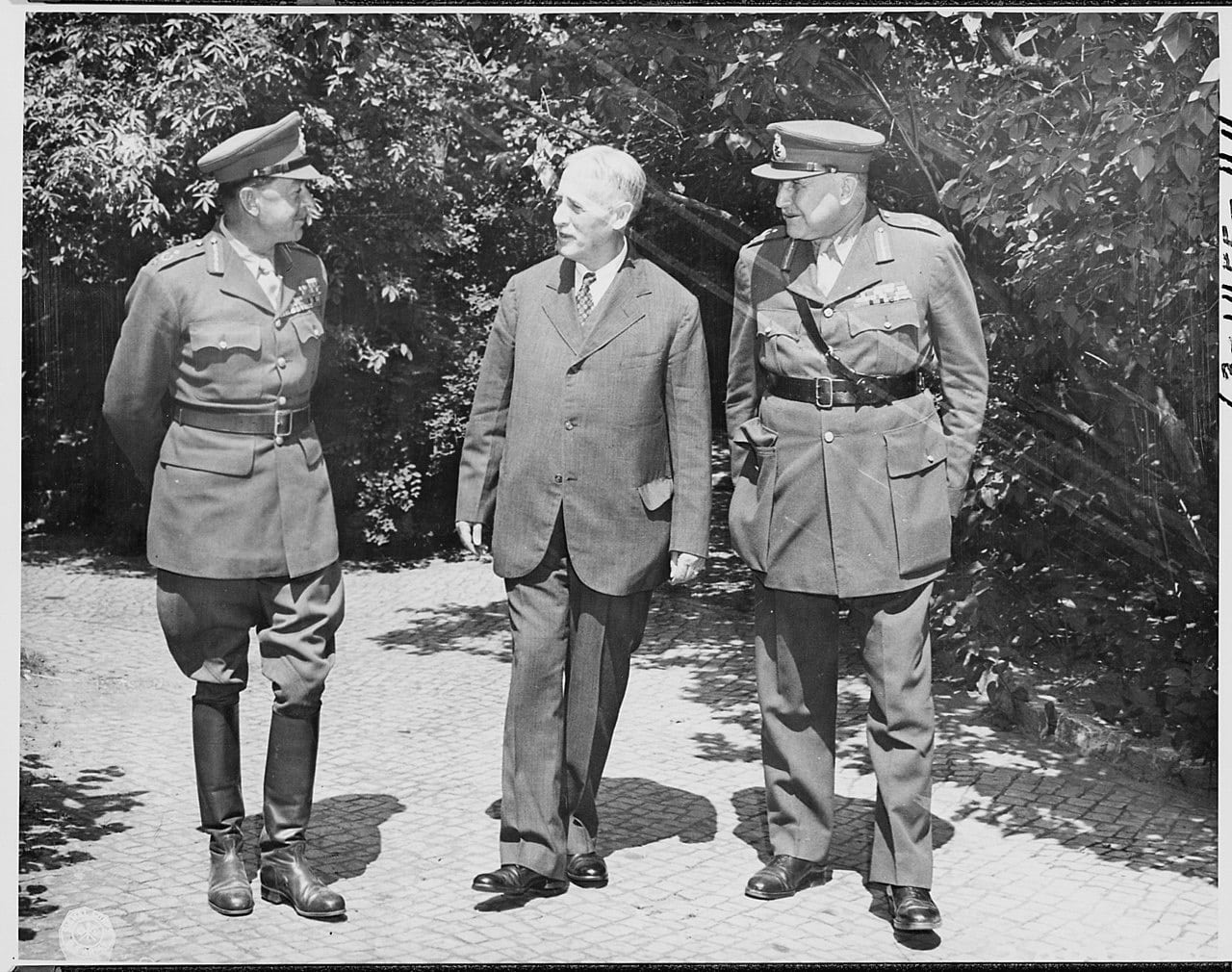

To demonstrate who was now jointly in charge of the former capital of Hitler’s ‘Thousand Year Reich’, some 10,000 men along with tanks, armored cars, searchlight batteries and artillery formations marched along Berlin’s monumental Charlottenburger Chaussee as Churchill proudly gazed on with Anthony Eden, Clement Attlee, and Field Marshals Montgomery, Wilson, Alexander, and Allan-Brooke.

The street had been one of Berlin’s finest, a tree-lined boulevard running through the city’s central park toward the Brandenburg Gate. Now most trees were suspiciously absent and the street strewn with rubble after years of Allied aerial bombardment and the final Soviet ground assault on the city during the Battle of Berlin.

This British Victory parade was the largest and most significant of its kind, but it was not the first time in 1945 that the British had organized a parade in Berlin.

- On July 2nd, the first British troops entered the city and took up residence in the barracks at Spandau.

- On July 4th, in the Spandau district of Berlin, the British celebrated their official take over their sector of the city. According to a young officer in the 11th Hussars, Richard Brett-Smith, it was a “tired and dusty” affair, more like “a sober liberation than a triumphant entry into a conquered city”

- On July 6th, the Union Jack flag was raised at the side of the Franco-Prussian War Memorial on the Grosser Stern in the center of the Tiergarten.

- On July 12th, Field-Marshal Montgomery led a ceremony investing Soviet Marshal Zhukov with the Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath (GCB) And Marshal Rokossovsky with the Knights Commander of the Order of the Bath (KCB).

- On July 13th the 7th Armoured Division plus the Grenadier Guards marched past the four Allied commanders of Berlin: Major-General Lyne (GB), Colonel-General Gorbatov (USSR), Major-General Floyd Parks (US) and General de Beauchesne (France).

- On July 15th, Winston Churchill was greeted by a guard of honor when he arrived at Gatow airport for the Potsdam Conference.

By 11:15am the parade had finished and Churchill left to officially open the armed services “Winston Club” – formerly the Kabarett der Komiker – on the Kurfürstendamm at its junction with Lehniner Platz. Here he addressed the 7th Armoured Division and, in particular, the 11th Hussars:

“Now I have only a word more to say about the Desert Rats, They were the first to begin. The 11th Hussars were in action in the desert in 1940 and ever since you have kept marching steadily forward on the long road to victory. Through so many countries and changing scenes, you have fought your way. It is not without emotion that I can express to you what I feel about the Desert Rats.

Dear Desert Rats! May your glory ever shine! May your laurels never fade! May the memory of this glorious pilgrimage of war which you have made from Alamein, via the Baltic to Berlin never die!

It is a march unsurpassed through all the story of war so as my reading of history leads me to believe. May the fathers long tell the children about this tale. May you all feel that in following your great ancestors you have accomplished something which has done good to the whole world; which has raised the honour of your country and of which every man has the right to feel proud.”

–

It was now the following day and Stimson – along with Special Assistant to the Secretary of War, Harvey Bundy – made his way back to Churchill’s villa just after 10:30AM to present Grove’s report to the British delegation.

Churchill would now have a chance to read the details for himself and to learn exactly what had gotten Truman “all pepped up” the day before.

“Now I know what happened to Truman yesterday,” Churchill quietly said as he looked up at Stimson. “I couldn’t understand it.”

The Prime Minister went on to tell Stimson that it was obvious that Truman was much more fortified by something that had happened and that he stood up to the Russians in a most emphatic and decisive manner – telling them as to certain demands that they absolutely could not have and that the United States was entirely against.

Churchill was alluding to a specific moment at yesterday’s session when Stalin spoke up about the importance of the three governments issuing a statement that would renew diplomatic relations with the former German satellite nations of Romania, Bulgaria, and Finland.

Reiterating his position from the plenary session the day before, Truman lashed out and said:

“We will not recognize these governments until they are set up on a satisfactory basis!”

The word ‘satisfactory’ in this particular case meant that these nations would set up their own freely elected governments without any kind of outside influence or pressure, particularly coming from the Soviet Red Army who currently had a large presence of occupying forces in them.

Churchill went on to say that he felt that Truman was a changed man and gave his account of how Truman told the Russians just where they got on and off, and “generally bossed the whole meeting.” The Prime Minister was now not only not worried about giving the Russians information of the matter, but according to Stimson:

“Churchill was rather inclined to (now) use it as an argument in our favor of negotiations.”

The sentiment felt among all who were present at Churchill’s villa that morning was unanimous in thinking that it was advisable to tell the Russians that they were at least working on that subject and intended to use it if and when it was successfully finished.

–

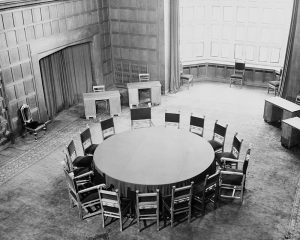

The sixth plenary session was called to order at 5:10pm. Although the question of what to do with Italy’s colonies was briefly discussed – which was eventually deferred to the Council of Foreign Ministers to include in their drafting of the future peace treaty – the largest issue on the agenda today was once again Poland.

It is important to understand that there were two Polish representing bodies that were ready to form a new government in Poland. On the one hand there was the pro-Soviet Lublin Committee that had been established by communists in Poland toward the end of WWII in the summer of 1944. Formally recognized by the Soviet Union, it was de facto serving as the official provisional government in Poland. On the other hand were the American and British backed ‘London Poles’ who had been in exile in Great Britain. They had retained the recognition of the United Kingdom and the United States throughout the course of the war, but now they were essentially considered redundant as the Big Three looked to agree on an international settlement when it came to the future of Poland’s government.

At Yalta, the Big Three agreed to the establishment of the ‘Provisional Government of National Unity’, which would be headquartered in Warsaw and comprising both representatives from the Lublin Committee and the London Poles.

At yesterday’s plenary session, however, Stalin had informed Truman and Churchill that a Polish Administered Area, consisting of representatives from the Lublin Committee, had been established at the start of the western front from the Oder River and stretching to Germany’s 1937 borders in the east. Furthermore, Stalin also claimed that all the ethnic Germans in this area had left after President Truman had inquired about the “nine million” of them spread throughout that territory.

During today’s session, Stalin remained firm on his position when it came to the western frontier of Poland and thus the probable seizure of Germany’s resources:

“I shall not undertake to oppose Mr. Churchill’s views on all these points, but I will deal here only with two. One, Germany will have resources in the Ruhr and the Rhineland, so there is no great difficulty if the Silesian coal basin is taken from Germany. Two, the movement of population does not present the difficulties Mr. Churchill anticipates. There are neither eight nor six nor three million Germans in this area. There have been several call-ups of troops in this area. Few Germans remain. Our data can be checked. Could we not arrange for representatives of the Polish government to come here and be heard?”

President Truman’s main concern was that this ‘Polish Administered Area’ was essentially the creation of a fifth occupation zone, something that was made up of the Soviet-supported Lublin Committee and something that lacked the presence of the London Poles. He stated:

“The Allies recognize that Poland must receive substantial compensation in the north and west…But Poland has in fact been assigned a zone of occupation contrary to our agreement. We can agree, if we wish to give the Poles an occupying zone, but I don’t like the way the Poles have taken or been given their zone.“

The Prime Minister’s concern was more of a humanitarian one:

“The burden falls on us, the British in particular. Our zone has the smallest supply of food and the greatest density of population. Suppose the Foreign Ministers, having heard the Poles, cannot agree. Then there will be indefinite delay, at least until another meeting of the heads of government. I am anxious to meet practical problems due to the march of events.”

Yet, Churchill also had economic and political concerns too:

“(The Polish Administered Area) destroys Germany’s economic integrity, and puts an undue burden on the occupying powers… I think Marshal Stalin and I agree up to this point, that the new Poland should advance to the Oder. But the difficulty between the Marshal and me is that I do not go quite as far as the Marshal…(Furthermore) Berlin draws its coal from the Silesian mines, which have long been worked by Polish miners. What is to happen to Berlin’s coal during the winter?”

Stalin: “Berlin draws her coal from Saxony. Let the Ruhr give her coal. There are different opportunities for supplying Berlin with coal.”

In order to clear the air, Stalin then reintroduced his suggestion that representatives from the ‘Polish Administered Area’ be invited to Potsdam to give their viewpoints on the current situation in their de facto zone. Understanding that this might be an alternative that would finally lead to some progress on a topic that had been going nowhere, Churchill withdrew his initial objection and agreed to having the Poles come to Potsdam to give an updated account on the matters at hand – something to which Truman also agreed.

Today’s session revealed some of the largest frustrations that the American and British delegations must have felt when it came to the Polish question at Potsdam.

At the end of the day, both the President and Prime Minister wanted free and fair elections – without any outside influence – to play out in Poland. They hoped that the London Poles could be a part of a plan to ensure this. However, as long as the Soviet Army occupied large parts of Eastern Europe, particularly in Poland, their words carried little weight, bomb or no bomb – fortified confidence or not. They feared that the occupying Soviet forces were working behind the scenes in the establishment of new governments that would ultimately be sympathetic to Moscow and they could not have been more correct, especially when one considers one of Stalin’s most notorious quotes that he is said to have made in a conversation in April 1945:

“Whoever occupies a territory also imposes on it his own social system…as far as his army can reach.”

**

Our Related Tours

To learn more about Potsdam and visit the site of the Potsdam Conference, have a look at our Glory Of Prussia tours.

To learn more about the history of Cold War Berlin and life behind the Iron Curtain; have a look at our Republic Of Fear tours.

Bibliography

Byrnes, James (1947). Speaking Frankly. New York: Harper & Brothers. ISBN 978-0-837-17480-8

Cullough, David (1992). Truman. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-86920-5

Fabian, Nadine. “Ein Besuch in der Stalin-Villa in Potsdam.” Märkische Allgemeine. 23 August 2017, https://www.maz-online.de/Lokales/Potsdam/Ein-Besuch-in-der-Stalin-Villa-in-Potsdam

Neiberg, Michael (2015). Potsdam: The End of World War II and the Remaking of Europe. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-07525-6

McBaime, Albert (2017). The Accidental President. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0-544-61734-6

Miscamble, Wilson D (1978). Anthony Eden and the Truman-Molotov Conversations, April 1945

Roberts, Geoffrey (2007). Stalin at the Tehran, Yalta, and Potsdam Conferences

Smyser, William (1999). From Yalta To Berlin: The Cold War Struggle Over Germany. New York: St. Martin’s Press. ISBN 0-312-06605-8

Sternberg, Jan. “Churchill und die lila Plüschmöbel.” Märkische Allgemeine. 13 July 2015, https://www.maz-online.de/Thema/Specials/P/Potsdamer-Konferenz/Villa-Urbig-am-Griebnitzsee.

Truman, Harry S. (1956). Memoirs: Year of Decisions Volume 1. New York: Doubleday.