Throughout his entire stay at Babelsberg, President Truman’s personal and official messages – including those from the War Department in Washington – arrived just down the street at the Army message center at today’s S-Bahn Griebnitzsee train station.

All correspondence addressed to the President was immediately decoded upon arrival and then taken to the ‘Little White House’ where they were delivered to the officers on duty in the Map Room, before they were then finally given to the President.

Late last night, another urgent top-secret cable to Truman was received and decoded, but held for delivery until this morning. When the President woke up, he came down to breakfast and read:

“The time schedule on Groves’ project is progressing so rapidly that it is now essential that the statement for release by you be available no later than Wednesday, 1 August…”

Time had now run out and the final decision to use the atomic bomb was now urgently needed.

For Truman, there were two options: First, go ahead with the invasion of Japan in early November and risk between thirty to fifty thousand American casualties, which was what the United States Army Chief of Staff George Marshall had projected on June 18 when Truman authorized ‘Operation Downfall’. Or second, deploy the atomic bomb and avoid the invasion, the ground war, and never seeing Marshall’s projections ever come to fruition.

Years later, Truman would say:

“In order to end the War and save American lives, the bomb had to be used.”

And he used it.

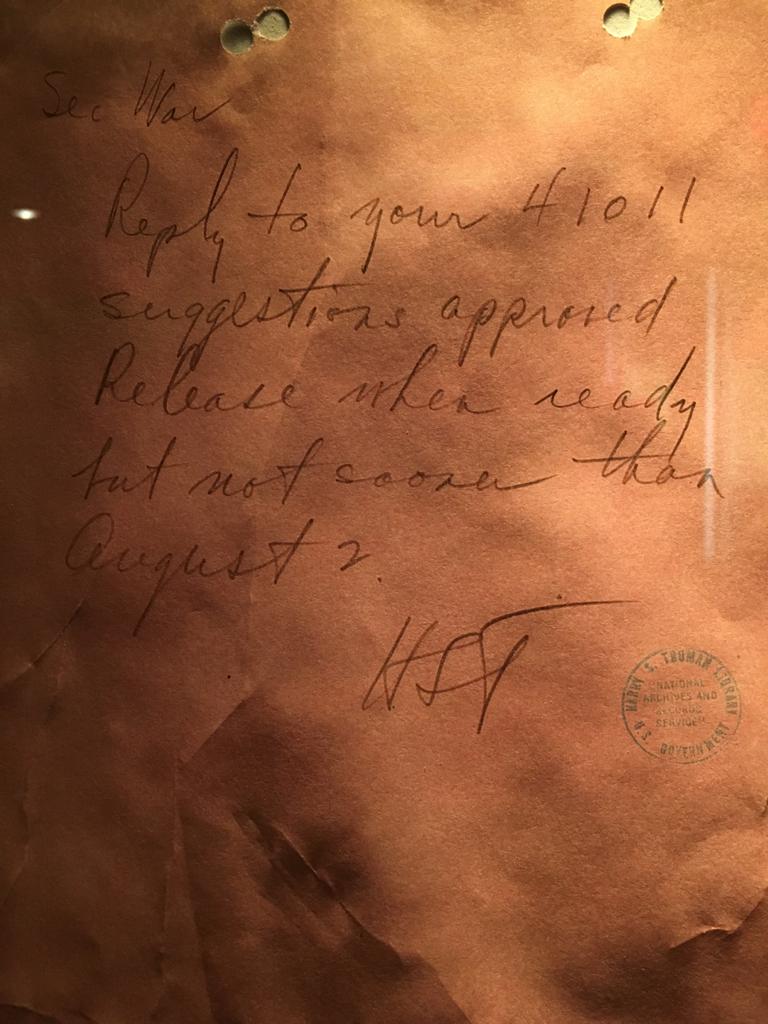

On this day in 1945, at 7:48AM Berlin time, President Truman turned over the pink message from Washington and wrote large and clear with a lead pencil on the backside:

Sec War

Reply to your 41011 suggestions approved.

Release when ready but not sooner than August 2.

HST

The decision had now been made to use the most terrible weapon ever created on what would be two densely populated cities in Japan. In his message to the Secretary of War, Truman did not put any limitations on the use of the atomic bomb, which meant that its release was now up to the military until he felt it was time to put its use back into his control.

Years would pass and academics would argue that the United States could have forced the Japanese to surrender without the bomb by continuing to blockade its mainland; some historians have argued that the United States could have been clearer with its message of ‘unconditional surrender of the Japanese armed forces’ proclaimed in the Potsdam Declaration – that is, highlighting the fact that the armed forces were to surrender unconditionally and not Japan’s Emperor; some have claimed that the President could have warned the Japanese with a demonstration bomb, showing the sheer horror of what an atomic bomb could do if dropped on one of its cities.

But the bombing campaign of World War II had changed so dramatically that the ethics of using an atomic bomb were not a priority for Truman at this stage in the war. As far as he was concerned, dropping it on Japan was not going to cross any moral lines that had not already been crossed. With the tens of thousands of civilians who became a target in the RAF and USAAF raids on Dresden in February 1945, coupled with the estimated 100,000 Japanese who were killed during the bombing of Tokyo in March, there was nothing that the atomic bomb could do that was going to change the nature of the bombing campaign. In short, instead of dropping several hundred bombs on a city, this was just going to be one single bomb.

Truman stated years later:

“The final decision of where and when to use the atomic bomb was up to me. Let there be no mistake about it. I regarded the bomb as a military weapon and never had any doubt that it should be used. The top military advisers to the President recommended its use, and when I talked to Churchill he unhesitatingly told me that he favored the use of the atomic bomb if it might aid to end the war.”

–

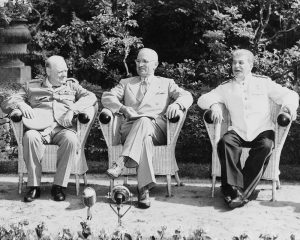

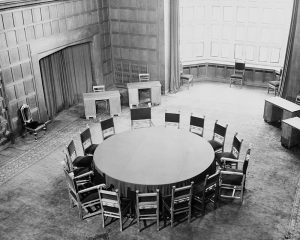

After a two-day interruption due to Stalin’s indisposition, the long-awaited eleventh plenary session was finally called to order at 4:05pm at Cecilienhof.

Following British Foreign Minister Bevin’s report on the tenth meeting of the Foreign Ministers from the previous day, Truman – homesick and eager than ever to leave Germany and return to Washington – wasted no time and immediately said with authority:

“The first point on the agenda is the United States proposal regarding reparations, Polish frontier, and admission into the United Nations of various categories of states.”

It was time to get down to business on the three most contentious topics of the Conference so that the Big Three could finally wrap this summit up. Indeed, these subjects were all different, but in many ways they were connected since they had been hovering over the Conference for two weeks now.

Each delegation felt it necessary to present their own proposal for consideration. Secretary Byrnes immediately spoke up and said:

“The United States proposes that 25 percent of the industrial capital equipment determined to be unnecessary for the peace economy should be exchanged for an equivalent of food, coal, potash, timber and other articles from the Soviet zone and an additional 15 percent of such equipment not necessary for peace economy should be removed and transferred to the Soviet Union on reparation account without further consideration. In our original proposal this equipment was to come from the Ruhr zone.”

“In the foreign secretaries’ meeting the British said they could not agree if exactions were from the Ruhr only but could agree if they came from the three western zones. It was agreed that the only difference would be one of percentages and that the percentage would be just one-half of what was in the American proposal regarding the Ruhr; that is if all the unneeded equipment in the western zones is included, the percentages would drop to 12½ and 7½ percent.”

The Ruhr region in western Germany, which included the well-known cities of Duisburg, Dortmund, Gelsenkirchen, and Essen, was one of Germany’s largest urban areas and most industrial regions at that time. Not only did it contain a wealth of industrial equipment, but it was also an area desperately in need of food supplies to feed a population that now had utterly nothing after the war. But the biggest problem that the Foreign Secretaries could not figure out up until this point was whether or not the Soviets should receive industrial equipment from just the Ruhr, or from the American and French zones as well. If it was decided to take equipment from all three Western zones, then Byrnes’s figures would have to be cut in half. Bevin then stated:

“In regard to percentage, we thought we had met you yesterday by agreeing to 12½ and 7½. We thought that was very liberal.”

“That was not liberal—just the opposite,” Stalin replied.

“But it was generous,” Bevin immediately fired back.

Stalin then stated the obvious and said, “Well, we have a different point of view.”

Byrnes then pointed out that the United States agreed with the British’s numbers and felt that they were better from an administrative point of view – not to mention, more advantageous to the Soviets as there would now be a variety of industrial equipment available from all over the Western zones. Unfortunately, Stalin was not budging. Bearing in mind that his nation had made the greatest contribution to victory over Nazi Germany and given the fact that his country’s plants and towns had been laid waste by the Germans during the war, Stalin said:

“…Not only the Ruhr but all zones should be considered…I think 15 and 10 is fair.”

After a brief pause, “Well, I will agree,” Bevin said.

In other words, 15% of compensated deliveries of industrial equipment were to be shipped to the Soviet Zone from not just the Ruhr, but from all Western zones of occupation. In exchange, the Soviets promised to ship the equivalent of food, grains, and other commodities to help feed the populations in the Western zones, something that had been agreed upon at the meeting between the Foreign Ministers on the day before. In addition, Stalin was able to negotiate an additional 10% of unneeded German industrial equipment from the Western zones without having to pay any compensation. Moreover, it was also decided during this discussion that France would be added to the Reparations Commission for the purpose of determining equipment available for reparations, now that all three zones would be affected. The Committee was given six months to determine the amount available for reparations.

Stalin’s proposed numbers might not have been exactly what the Foreign Ministers agreed upon the day before, but after fifteen days of grueling negotiations on the subject, it was considered to be ‘close enough’ for the Anglo-American delegations. After all, it was now a matter of making concessions for the sole purpose of reaching compromises in order to bring the Conference to an end. With no objection from the American delegation, President Truman then said:

“The next question is Poland.”

The Soviets had submitted their proposal that would – for the time being – shift Poland’s western frontier farther westward to Stettin and would run south along the Western Neisse River from there. Bevin began this discussion with a rather impassioned statement, which mirrored the kind of compassionate and concerned tone in which Churchill spoke over the postwar future of Poland at the outset of the Conference:

“I have been instructed to hold for the eastern Neisse. Does it mean that the zone will be handed over to the Poles entirely and that the Soviet troops will be withdrawn? I have met the Poles on this question and in the light of the declaration in the United States document, I have asked them what their intention really is because any change of a territory must be defended in Parliament. That defense will be affected but what will happen in the new Poland? I asked the Poles their intention in regard to free election[s] on universal suffrage. They assured me that they will hold elections as soon as possible, not later than January, 1946, subject to conditions beyond their control. They also agreed to the freedom of the press. They gave assurance on the freedom of religion. But one very important matter is repatriation of troops. I asked them if they would make a declaration so we would be sure that they would receive equal treatment. Another point which concerns the Soviets and ourselves that the Poles can not settle with us is the establishment of an air service between Poland and London so as to enable His Majesty’s Government to maintain regular communications with the embassy at Warsaw. I would like an agreement on that immediately. In the United States document it says the area is under the administration of Polish state and not part of Soviet occupation. That means it is under Poles for all matters.”

Bevin’s heart was in the right place as he expressed concern for the future of a free Poland. After all, it was the cause for which the United Kingdom had entered World War II in the first place and he wanted to be crystal clear that Poland would not be part of Soviet occupation, but would soon hold elections and establish a self-supporting democratic government.

“We have already removed four divisions of our troops and we contemplate further reduction by agreement with Polish government. This zone is now actually administered by the Poles,” Stalin assured the British Foreign Minister.

As long as the Allies would maintain constant communication with the Poles to ensure the new government functioned democratically – and despite the fact that the British wanted the boundary to be the Eastern Neisse River – it was now time for the Anglo-American delegations to compromise over borders just as the Soviets had compromised earlier by withdrawing its demand that Germany pay a monetary figure in reparations.

When the compromise was finally reached, Truman stated, “This settles the Polish question.”

“Stettin is in the Polish territory,” Stalin added.

“Yes, we should inform the French,” Bevin concluded.

And with that, Poland’s western borders were now temporarily agreed upon until a final, internationally binding agreement would be established at the future peace conference when an actual peace treaty would be signed.

After talking briefly about prosecuting Nazi war criminals and whether or not the Allies should list names when compiling their list of whom to prosecute, the Big Three decided to wait and discuss it – along with the future of Romania, Bulgaria and Hungary – tomorrow, in addition to tying up any loose ends that needed to be addressed. The Foreign Ministers would meet in the morning, prepare an agenda, and present it to the Big Three tomorrow afternoon.

The Potsdam Conference had now turned the corner to make its way down the final stretch.

**

Our Related Tours

To learn more about Potsdam and visit the site of the Potsdam Conference, have a look at our Royal Potsdam tours.

To learn more about the history of Cold War Berlin and life behind the Iron Curtain; have a look at our Republic Of Fear tours.

Bibliography

Byrnes, James (1947). Speaking Frankly. New York: Harper & Brothers. ISBN 978-0-837-17480-8

Cullough, David (1992). Truman. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-86920-5

Fabian, Nadine. “Ein Besuch in der Stalin-Villa in Potsdam.” Märkische Allgemeine. 23 August 2017, https://www.maz-online.de/Lokales/Potsdam/Ein-Besuch-in-der-Stalin-Villa-in-Potsdam

Neiberg, Michael (2015). Potsdam: The End of World War II and the Remaking of Europe. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-07525-6

McBaime, Albert (2017). The Accidental President. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0-544-61734-6

Miscamble, Wilson D (1978). Anthony Eden and the Truman-Molotov Conversations, April 1945

Roberts, Geoffrey (2007). Stalin at the Tehran, Yalta, and Potsdam Conferences

Smyser, William (1999). From Yalta To Berlin: The Cold War Struggle Over Germany. New York: St. Martin’s Press. ISBN 0-312-06605-8

Sternberg, Jan. “Churchill und die lila Plüschmöbel.” Märkische Allgemeine. 13 July 2015, https://www.maz-online.de/Thema/Specials/P/Potsdamer-Konferenz/Villa-Urbig-am-Griebnitzsee.

Truman, Harry S. (1956). Memoirs: Year of Decisions Volume 1. New York: Doubleday.