Secretary Stimson made his way to the ‘Little White House’ early this morning to meet with President Truman. Manhattan was nearing completion, loose ends were currently being tied, and Stimson wanted to be kept in the loop of what was going on at the plenary sessions since he was not allowed to sit in on the official sessions at Cecilienhof.

In order for him to structure his daily military agenda accordingly and more conveniently, he therefore asked the President if he could drop in early every morning and talk with either him or Byrnes about the events of the preceding day. Truman immediately told Stimson that he would be glad to meet with him on a daily basis to talk these matters over.

Today Stimson informed the President that a warning message to Japan was nearly ready – an ultimatum that would become famously known as the ‘Potsdam Declaration’, providing Japan with one last chance to surrender unconditionally or face immediate annihilation.

Interestingly, Stimson mentioned to Truman that he felt it was unwise to insist on unconditional surrender at this time. Again, this was a term that the Japanese would take to mean that they could not keep their Emperor, and thus making it more difficult to achieve peace. Therefore, Stimson urged a revision of sorts that read somewhere along the lines that the Allies would remain committed to the war against Japan until the country ceased to exist.

Although not present at this meeting, Truman knew right away that Bynres and most of his Cabinet – which were all Roosevelt’s picks – would be vehemently opposed to any sort of change to the unconditional surrender demand this late in the game.

It was a central aim that the Truman administration had inherited from Roosevelt that was too long established and too often proclaimed. It evoked the American spirit of fighting and winning the war against Japan ever since Pearl Harbor had been deliberately and viciously attacked in December 1941. Furthermore, unconditional surrender was what Nazi Germany had been forced to accept, and its renunciation with the Japanese at this late date – after so much bloodshed and with victory now in sight – would have seemed like appeasement and have been politically disastrous.

According to Truman biographer David McCullough:

“To most Americans, Hirohito was the villainous symbol of Japan’s fanatical military clique. A Gallup Poll in June had shown that a mere fraction of Americans, only 7 percent, thought he should be retained after the war, even as a puppet, while a full third of the people thought he should be executed as a war criminal.” Secretary Byrnes considered any negotiations with Japan over terms of surrender a waste of time and felt that if Hirohito were to remain in place, the war would have been pointless.”

Although it is safe to say that Truman appreciated Stimson’s suggestion and listened to him carefully, there was no way the Secretary was going to convince the President otherwise.

–

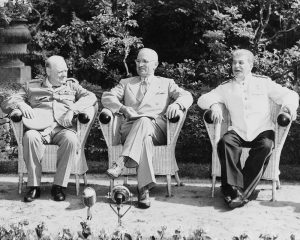

Today was an eventful day at the Cecilienhof Palace, as it facilitated several meetings prior to the late afternoon plenary session between the Big Three.

The day got underway at 9:30am with a meeting between the American and British Joint Chiefs of Staff, followed by the sixth meeting of the Foreign Ministers at 11:30am. There were also several on and off-the-record conversations that took place throughout the day between the foreign ministers, the heads of state, and sometimes between a head of state and a foreign minister.

And this was a usual run-of-the-mill day at Cecilienhof.

Sometimes negotiations began as early as 8:00am with consultations in the subcommittees usually lasting until late morning when Byrnes, Eden, and Molotov sat down at the palace’s roundtable around 11:00am to discuss important questions and to construct the Big Three’s agenda for that particular day. It was not until late in the afternoon – usually between 4:00-5:30pm – that Churchill, Truman, and Stalin assembled for their round of discussions, which were interpreted simultaneously into English and Russian.

Due to the importance of security and confidentiality, each delegation member had a special pass for the Conference which had to be carried at all times. Journalists, on the other hand, were not admitted to the conference area except for on rare occasions when a handful were carefully vetted and allowed to be present for an official photoshoot either at the palace or at one of the Big Three’s villas. All other journalists and photographers mostly had to report on the events from the sidelines.

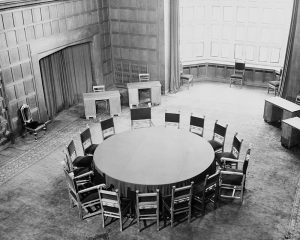

The organizational and technical preparations for the conference were placed in the hands of the support services of the Red Army under the leadership of Lieutenant General Nikolai Aleksandrovich Antipenko, the Deputy Commander in Chief for Rear Service of the 1st Belorussian Front. The ‘Main Hall’, which served as the primary living room during the days the Crown Prince and his family lived there, was used as the main conference room.

Of the other 175 rooms inside the Cecilienhof Palace, around 35 of them were rearranged, put in order and furnished to be used as offices.

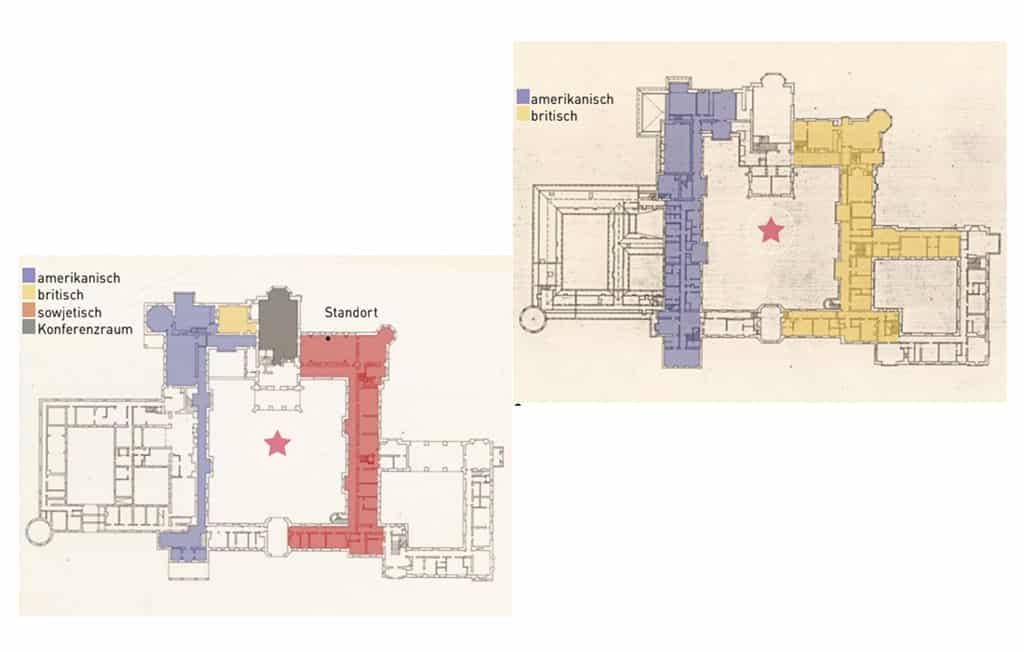

All three delegations were given their own separate area from which to prepare or to briefly convene before each plenary session got underway. The American and Soviet delegations were on the ground floor, with the Americans in the west wing of the palace and the Soviets in the east wing. The British were also in the east wing, but situated a floor above the Soviets.

Churchill, Stalin and Truman also had their own individual, yet equally sized entrances that led from their delegation’s area into the conference room. Since matters of protocol and official formalities were extremely important and fully enforced at all times, this ensured that no individual leader received special treatment or exercised a higher status during the Conference. As a matter of fact, Churchill found out firsthand how important the Soviets upheld protocol from day one when he was forced to take a long detour to the conference room from the rooms he used on the second floor. According to eyewitness testimony from an administrative officer for the British Delegation:

“The easiest way for the Prime Minister to reach the conference room from his upstairs suite was to come down the main staircase and go through the double doors. But this door was locked. I asked the commandant, who was showing me round, whether it could be opened and so save Mr. Churchill having to traverse an extra length of corridor. He shook his head. ‘Not possible,’ said the interpreter, ‘they use the three smaller doors, one each!’ The intention became obvious to me; they must sit coequal at the round table, their entrances and exits must be through doors of the same size.’

At the end of June 1945 and just days before their armies would officially take over their occupation sectors in Berlin, a handful of American and British military personnel had made their way to Potsdam to inspect the conference location, as well as the living quarters in Babelsberg. Although the Americans quickly confirmed that the Soviets had put the palace and the grounds into exceptional condition, the British were painfully critical of Cecilienhof’s design, which had been constructed based on English mock-Tudor architecture.

“Cecilienhof is a country house in pseudo-Tudor style with 176 rooms, the facade overblown with plaster, broken with fake Elizabethan windows and stone portals which seem to be somewhat embarrassed by the lack of moats and drawbridges. The crowning glory is a series of chimneys, some taking their inspiration from the Islamic style, some reminding one of the pillars of the baldchin in St Peters. Taken altogether, it comes closest to resembling the rooftops of Nottingham in the nineteenth century. In this unpleasant neo-Tudor place, which could have been designed by a crazy illustrator of children’s books, the Russians have now brought furniture collected from all over Potsdam. Massive old-style German armchairs, decorated with carved lion heads, stand imperiously on French carpets…the walls defaced with pictures of wondrous maritime scenes and boring little pictures of village streets.”

Apparently, the German architect Paul Schultze-Naumburg – who designed Cecilienhof – and Ludwig Troost – who designed much of the interior – should have taken a few pointers from the British military before they had finalized their plans (if only they had had a crystal ball).

–

The Potsdam Conference’s seventh plenary session was called to order today at 5:10pm. Although there was some discussion about accessing and administering the Rhine and Danube rivers, along with Allied policy in the Middle East, the topic over future Soviet control of Königsberg – currently a piece of German territory in East Prussia – dominated much of this session’s discussion.

As early as the Tehran Conference, Stalin raised the issue of future Soviet control of Königsberg owing to the fact that the Soviet Union had no ice-free ports in the Baltic. Neither Churchill or Roosevelt objected, but they thought it would be best to address the issue of Königsberg while dealing with the general topic of Germany’s borders to the east. In the end, a basis for future discussion resulted with the Big Three agreeing that Germany was to lose Königsberg and all the territory east and northeast of the Oder River, as well as some territory south of the Oder in Silesia. The shape and size of this territory, however, remained unclear for the time being.

Months later in October 1944, Churchill flew to Moscow for a conference with Stalin. While discussing the Lublin Committee’s recent arrival in Poland and the future of Germany, Stalin reiterated his claim for Königsberg, but ended up agreeing with Churchill that no firm decision could be made without Roosevelt’s participation at another summit. When the three leaders met a few months later at Yalta, Stalin once again brought up the topic of Königsberg while discussing the postwar setting in the Baltic regions, and once again there were no objections from the British and Americans.

Not only was Königsberg a warm-water port city that would allow the Soviets to carry on trade and commerce throughout the winter to enhance its overall geopolitical and economic interests, but it was also a historically symbolic piece of Germany.

The Berlin based House of Hohenzollern – the German ruling dynasty that produced the Prince Electors of the Holy Roman Empire, Prussian kings, and German emperors – inherited the Duchy of Prussia in the 16th century and as a result came in possession of the Prussian port city of Königsberg. A couple of centuries later in 1701, it was here that Elector Friedrich III of Brandenburg, crowned himself King Friedrich I in Prussia and then made his way back to his permanent home in Berlin and Potsdam. The Kingdom of Prussia would go on to play a pivotal role in shaping the politics and history of central Europe for over the next two centuries. It produced some of the most historic kings, like Friedrich der Große (Frederick the Great), who would expand Prussian hegemony and increase its influence throughout the continent. Now, with the collapse of the German empire in 1918 and the total and utter defeat of Germany in 1945, Churchill, Stalin and Truman sat in Frederick the Great’s great-great-great-great-great nephew’s palace – almost 159 years to the date when he passed away just a couple miles away at the Sanssouci Palace – to make a decision on the historic roots of Prussia.

What was different about the discussion this time around, compared to the previous times, was that Soviet lives had been lost in great numbers over the port city.

The Soviets had initially surrounded Königsberg in January 1945, with attacks and conflict erupting over the next few months between the Red Army and various German units. It was not until April 6th that the Soviets launched a vicious and bloody street-to-street battle lasting four days to capture Königsberg from German defenders. In the end, almost 80% of Königsberg was destroyed – part of that destruction resulting from the RAF’s bombings in August 1944 – and the Soviets would eventually expel around 200,000 of the German residents who had remained in the city at the end of the war. While the exact number of Soviet casualties remains unknown, some Russian sources state at least around 4,000 were killed.

When it came time to talk about Königsberg at this evening’s session, Stalin displayed the same attitude he held before, but now he had more with which to justify his demands:

“We consider it necessary to have, at the expense of Germany, one ice-free port in the Baltic. It is only fair that the Russians, who have shed so much blood and lived through so much terror, should want to receive some lump of German territory that would give some small satisfaction from this war. Neither the President nor the Prime Minister raised any objection at Yalta, so the question was agreed upon. We are anxious to have that agreement confirmed at this conference.”

Churchill replied that the British government sympathized with Russia’s desires, and Truman did not have any objection in principle, but stated that “technical and ethnic details must be considered”.

With the expulsion of 200,000 residents from Königsberg well underway, it is unfortunate that the President did not elaborate on what he meant by ‘technical and ethnic details’ to make the Soviet takeover of the port city more humane. In any event, after no more than a minute of debate, almost 400 years of German territory was now to be handed – in principle – over to the Soviets, who would rename the city ‘Kaliningrad’ after famed Bolshevik Mikhail Kalinin’s following his death a year later, in 1946.

After today’s session was adjourned, it was now the Prime Minister’s turn to host tonight’s dinner party. He had already promised that he would ‘get even’ with the Soviets and Americans, alluding to their lavish and splendid dinner parties in recent days.

Churchill had invited the entire British Royal Air Force Orchestra to play that evening while the Big Three indulged in copious amounts of delicacies and drinks.

Amusingly, Stalin arrived at Churchill’s dinner party in a bulletproof limousine with some fifty armed guards, while Truman showed up on foot with Byrnes, Leahy, and three secret service men as if they were out for a summer night’s stroll in the neighborhood.

**

Our Related Tours

To learn more about Potsdam and visit the site of the Potsdam Conference, have a look at our Royal Potsdam tours.

To learn more about the history of Cold War Berlin and life behind the Iron Curtain; have a look at our Republic Of Fear tours.

Bibliography

Byrnes, James (1947). Speaking Frankly. New York: Harper & Brothers. ISBN 978-0-837-17480-8

Cullough, David (1992). Truman. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-86920-5

Fabian, Nadine. “Ein Besuch in der Stalin-Villa in Potsdam.” Märkische Allgemeine. 23 August 2017, https://www.maz-online.de/Lokales/Potsdam/Ein-Besuch-in-der-Stalin-Villa-in-Potsdam

Neiberg, Michael (2015). Potsdam: The End of World War II and the Remaking of Europe. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-07525-6

McBaime, Albert (2017). The Accidental President. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0-544-61734-6

Miscamble, Wilson D (1978). Anthony Eden and the Truman-Molotov Conversations, April 1945

Roberts, Geoffrey (2007). Stalin at the Tehran, Yalta, and Potsdam Conferences

Smyser, William (1999). From Yalta To Berlin: The Cold War Struggle Over Germany. New York: St. Martin’s Press. ISBN 0-312-06605-8

Sternberg, Jan. “Churchill und die lila Plüschmöbel.” Märkische Allgemeine. 13 July 2015, https://www.maz-online.de/Thema/Specials/P/Potsdamer-Konferenz/Villa-Urbig-am-Griebnitzsee.

Truman, Harry S. (1956). Memoirs: Year of Decisions Volume 1. New York: Doubleday.