July 24th through July 26th were arguably the most crucial and deciding days of the Potsdam Conference.

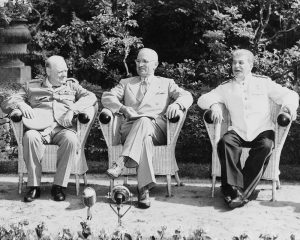

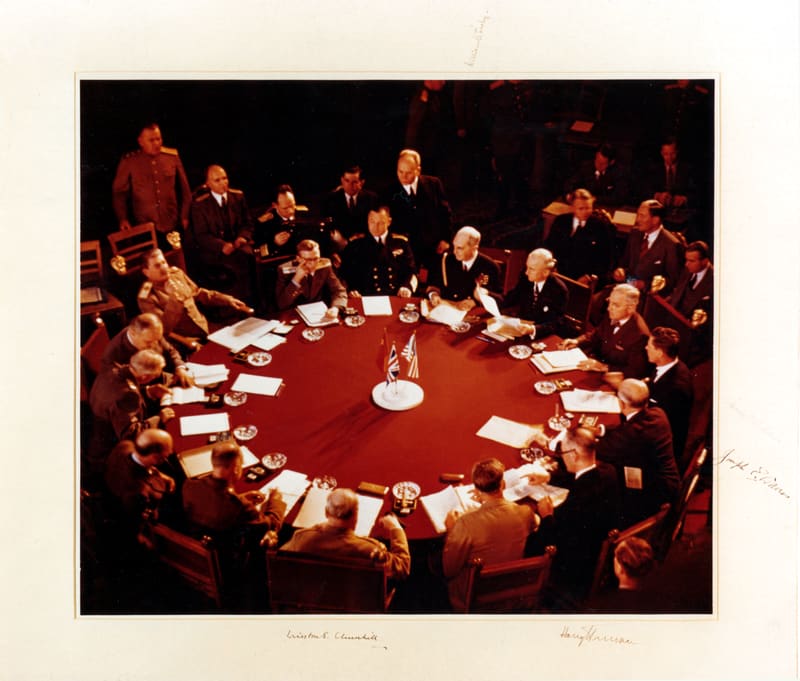

Yesterday’s plenary session proved to be the most dramatic one yet with Stalin being more difficult than ever before on the topic of Italy and the former Axis states in Eastern Europe. He accused Churchill that he had been the victim of “fairy tales” when the Prime Minister had pointed out that the British diplomatic mission had experienced an “iron fence” in Bucharest. And then there was the gripping spectacle of Truman walking around the conference table after the plenary session adjourned to disclose the secret of the atomic bomb to Stalin, ushering in the nuclear arms race of the 20th century.

Over the years, it has been the thesis of some historians that the birth of the atomic bomb played a crucial role at Potsdam and influenced the way Truman behaved toward Stalin and the Soviets. Prior to telling Stalin about the bomb, many have argued that Truman played it like a game of poker where he had drawn two aces – one down and one up.

The ace down was the atomic bomb and the ace showing was the United States’s military and economic power.

Therefore, Truman was able to put added pressure on the Soviets that he otherwise would not have done had the bomb not been developed yet. However, aside from Truman appearing “tremendously pepped up” following Grove’s full description of the atomic bomb’s test on July 16th and then being more assertive at the fifth plenary session on July 21st, Truman neither said nor did anything of consequence to support this theory. Furthermore, the whole idea that the atomic bomb crucially added influence to how Truman saw his relationship with Stalin would be vigorously denied by those who were present and witness to the events at Potsdam.

In the weeks before the atomic bomb’s test at Los Alamos, Truman reportedly remarked to some of his aides that if the bomb worked, he would “certainly have the hammer on those boys,” but whether he meant the Russians or the Japanese was unclear, and there was never any intimation of a “hammer,” nor was there ever a flaunting of power in his dealings with Stalin.

“The idea of using the bomb as a form of pressure on the Russians never entered the discussions at Potsdam,” wrote United States Ambassador to the Soviet Union, Averell Harriman, who was on the scene at Potsdam. “That wasn’t the President’s mood at all. The mood was to treat Stalin as an ally – a difficult ally, admittedly – in the hope that he would behave like one.”

–

The final preparations for issuing the Potsdam Declaration were almost complete.

The ultimatum was sent from the ‘Little White House’ yesterday to Patrick J. Hurley who was the United States Ambassador to China in Chungking. The proclamation needed the approval of the Chinese since they – who had already been at war with Japan since 1937 – joined the Allies in a formal declaration of war against Japan, Germany, and Italy within days after the United States declared war on Japan following the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941.

But this morning there was a bit of a setback when Truman and Byrnes came to find out that Ambassador Hurley had not yet received the draft of the Japanese ultimatum. Byrnes immediately ordered an investigation. As it turned out, Map Room officials at the White House had apparently handed the document to the navy to send. Unaware of the document’s importance, it just sat on a desk for five hours. Then it was eventually sent through Honolulu where it was further delayed. In the end, Ambassador Hurley finally cabled Truman and Byrnes that the ultimatum had reached him at 8:35pm Chungking time, arriving almost a day late. The Ambassador wrote:

“The translation was not finished until after midnight.”

And when the Ambassador tried to deliver the ultimatum to Chinese leader Chiang Kai-shek for his approval, the Chinese generalissimo was not at his palace but rather across the Yangtze River in the mountains. Therefore, Hurley had to catch a ferry to cross the river in the middle of the night to hunt Kai-shek down so that it could be approved and quickly sent back to Truman and Byrnes at Potsdam. It was now just a matter of hours before Japan would be given one last chance to surrender.

The delay had infuriated Truman and Byrnes because Truman had decided by this point that he would order the military to deploy the bomb if Japan rejected the ultimatum.

“We have discovered the most terrible bomb in the history of the world,” he wrote today in his diary shortly after the general military order was issued to the Air Force to proceed with the plan.

In short, Truman would still have to give the final order for its release, which mostly depended on Japan’s reaction to the Potsdam Declaration, but now the military was fully involved and preparing to carry out the mission to deploy it.

Interestingly, in that same diary entry, Truman also wrote:

“This weapon is to be used against Japan between now and August 10th. I have told the Sec. of War, Mr. Stimson, to use it so that military objectives and soldiers and sailors are the target and not women and children. Even if the Japs are savages, ruthless, merciless and fanatic, we as the leader of the world for the common welfare cannot drop that terrible bomb on the old capital or the new.”

In other words, he tried to assure himself that the bomb would be primarily used against a military target because no matter how bad the Japanese had been, it would be immoral and inhumane to kill women and children. However, he had to have some understanding that he was kidding himself in this entry. It really was wishful thinking to believe that innocent civilians would not become victims of its use. Especially when one considers the tens of thousands of civilians who were killed during the recent bombing raids in Dresden and Tokyo, President Truman was certainly well aware by this point that the use of the atomic bomb would be much more than a military target. But this is exactly what the bombing campaign of WWII had blossomed into by this point in the war: it now became a redefinition of what a legitimate target was – that is to say, a target was no longer just a city, but rather people in that city who were primarily noncombatants in what was a redefined, virtually total war where everyone became a target.

–

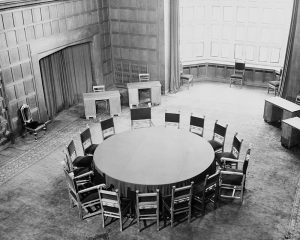

The ninth plenary session was called to order at the remarkably early hour of 11:30am today.

Some historians have written over the years that the reason why most sessions began around 5:00pm was because Churchill and Stalin could not have been bothered to get up before noon. This might be partly true – when one considers Churchill’s overall fatigue for politics and Stalin’s poor health at this time – but of course so many other meetings had to take place, particularly between the foreign ministers, before the plenary sessions in order to keep the official agenda and order of business afloat.

Today was different, however.

The early start was due to the fact that Churchill and his political opponent, Clement Attlee, would be returning to London this afternoon to find out the results of the British national elections that had taken place on July 5th, nearly two weeks before the Potsdam Conference began.

Indeed, Churchill’s coalition government had successfully led Great Britain through the war against Nazi Germany, but the Labour Party’s decision to pull out of the national wartime government on May 23rd forced a general election to take place. And on account of the approximately 1.2 million absentee ballots – primarily from soldiers stationed abroad – that still had to be counted, the outcome of the election could only be announced three weeks afterwards.

Today’s topic was once again Eastern Europe and Churchill got things kicked off:

“We must at sometime discuss the question of the transfer of populations. There are a large number of Germans to be moved from Czechoslovakia. We must consider where they are to go.”

“The Czechs have already evicted them,” Stalin replied.

“The two and a half million of them?” asked Churchill. “Then there are the Germans from the new Poland. Will they go to the Russian zone? We don’t want them. There are large numbers still to come from the Sudetenland.”

Stalin replied, “As far as the Poles are concerned, the Poles have retained one and a half million Germans to help as laborers. As soon as the harvest is over, the Poles will evict them. The Poles do not ask us. They are doing what they like, just as the Czechs are.”

By this point, Churchill was getting agitated. “That is the difficulty,” he said. “The Poles are driving the Germans out of the Russian zone. That should not be done without considering its effect on the food supply and reparations. We are getting into a position where the Poles have food and coal, and we have the mass of the population thrown on us.”

In an attempt to appear sympathetic to the feelings of Eastern Europe, Stalin replied, “We must appreciate the position of the Poles. The Poles are taking revenge for centuries of injuries.”

“So that consists in throwing them on us, and the United States?” asked Churchill.

Finally, Truman stepped up to the plate to deliver his thoughts.

“We don’t want to pay for Polish revenge. If Poland is to have an occupation zone, that should be clearly defined, but at the present time there are only four zones of occupation. If the Poles have an occupation zone they should be responsible for it. The boundary cannot be fixed before the peace conference. I want to be helpful, but Germany is occupied by four powers, and the boundary cannot be changed now; only at the peace conference.”

Tired, annoyed and full of frustration, Churchill then spoke up for the last time at Potsdam and finally called a spade a spade by stating what had been obvious up to that point: indirectly predicting what mostly turned out to be the case at the end of the Conference.

“If the conference ends in ten days without agreement on the present state of affairs in Poland, and with the Poles practically admitted as a fifth occupation power, and no arrangement for the spreading of food over the whole of Germany, it will mark the breakdown of the conference. I suppose we will have to fall back on our own zones…I do hope that we will reach a broad agreement, but we must recognize that we have made no progress so far on this point.”

The Prime Minister was leaving the conference at a very low point during his participation at Potsdam; like almost every other plenary session, Churchill’s last one had not gone so smoothly. As Truman plainly put it in a letter to his wife:

“There are some things we can’t agree on. Russia and Poland have gobbled up a big chunk of Germany and want Britain and us to agree. I have flatly refused. We have unalterably opposed the recognition of police governments in the Germany Axis countries. I told Stalin that until we had free access to those countries and our nationals had their property rights restored, so far as we were concerned, there’d never be recognition.”

Now, Churchill was leaving and nothing major had been accomplished at Potsdam.

After the official photographs had been taken in Cecilienhof’s west courtyard and after all the formal goodbyes had been exchanged, Truman said to the two Britons:

“I must say good luck to you both.”

“What a pity,” Stalin said. “Judging from the expression on Mr. Attlee’s face, I do not think he looks forward to taking over your authority.”

“I hope to be back,” Churchill replied.

As the Prime Minister turned for the exit, one of President Truman’s advisors, Ambassador Joseph Davies, watched him leave.

“There was a glint of a tear in his eyes,” the Ambassador recorded, “but his step was firm and his chin thrust out. He seemed to sense that he had reached the end of the road.”

**

Our Related Tours

To learn more about Potsdam and visit the site of the Potsdam Conference, have a look at our Glory Of Prussia tours.

To learn more about the history of Cold War Berlin and life behind the Iron Curtain; have a look at our Republic Of Fear tours.

Bibliography

Byrnes, James (1947). Speaking Frankly. New York: Harper & Brothers. ISBN 978-0-837-17480-8

Cullough, David (1992). Truman. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-86920-5

Fabian, Nadine. “Ein Besuch in der Stalin-Villa in Potsdam.” Märkische Allgemeine. 23 August 2017, https://www.maz-online.de/Lokales/Potsdam/Ein-Besuch-in-der-Stalin-Villa-in-Potsdam

Neiberg, Michael (2015). Potsdam: The End of World War II and the Remaking of Europe. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-07525-6

McBaime, Albert (2017). The Accidental President. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0-544-61734-6

Miscamble, Wilson D (1978). Anthony Eden and the Truman-Molotov Conversations, April 1945

Roberts, Geoffrey (2007). Stalin at the Tehran, Yalta, and Potsdam Conferences

Smyser, William (1999). From Yalta To Berlin: The Cold War Struggle Over Germany. New York: St. Martin’s Press. ISBN 0-312-06605-8

Sternberg, Jan. “Churchill und die lila Plüschmöbel.” Märkische Allgemeine. 13 July 2015, https://www.maz-online.de/Thema/Specials/P/Potsdamer-Konferenz/Villa-Urbig-am-Griebnitzsee.

Truman, Harry S. (1956). Memoirs: Year of Decisions Volume 1. New York: Doubleday.