President Truman called the third plenary session to order at 4:05pm and Churchill immediately kicked this session off by highlighting the current unrest in the Balkans.

“One point Marshal Stalin raised at the previous meeting concerned an incident on the Bulgarian-Greek frontier. I have made some inquiries, but the British government has heard of no fighting, but we know that these people do not like each other very much and I have no doubt that there has been some sniping.”

In April 1941, Nazi Germany invaded Greece to assist its ally, Italy, which had been at war with Greece since October of 1940.

Greece fell within a couple of months and its territory was then divided into occupation zones run by the Axis powers. Germany administered the most important regions of the country, which included Athens and Thessaloniki, while other parts, like the Dodecanese Islands and Western Thrace were administered by Italy and Bulgaria, respectively.

Liberation in Greece finally came in October 1944 when Germany withdrew from the mainland in the face of the Soviet Red Army’s advance toward the region.

Greece then annexed back these regions from Italy and Bulgaria following the collapse of Nazi Germany and its allies. Unfortunately, tensions quickly flared and the country would eventually descend into a bloody civil war between communist forces, which were being supported by the Soviets, and the anti-communist Greek government.

Churchill went on to claim that there was no Greek field division in northern Greece, which was something the British knew as they had their own people there, and discussed the fact, while citing certain figures, that there were many more troops on the borders in Albania, Yugoslavia and Bulgaria than there were in Greece .

“I mention this because this conference of the great powers should make clear that there should be no marauding attacks and that frontier questions should be settled by the peace conference,” Churchill stated. “It should be indicated that those who try to violate frontiers are likely to prejudice their own claims.”

Truman said that he had not heard about the unrest of which Churchill spoke in the Balkans, but agreed that matters should be settled by the peace conference and not by direct action. Stalin, on the other hand, aggressively denied that he had raised the question at a previous meeting, as Churchill stated, but had privately remarked about the matter to him and that he would give his views at a later time.

Churchill mistakenly thought it was presented at the roundtable, but Stalin stood by the notion that it was during a private conversation, and nothing about the Balkans had really been put on record at any of the plenary sessions up until this point.

This says a lot about the atmosphere at Potsdam and the amount of socializing and off-record discussions that took place at lunches and dinners; so much so that the heads of state were confusing official business with private conversations. In any event, the Generalissimo clearly did not appreciate their conversation being brought up and put on the record by a baffled Prime Minister.

–

British Foreign Minister Anthony Eden read out today’s agenda which included talks on what to do with the German Navy and merchant marine; Spain; Yalta Declaration on a liberated Europe; Yugoslavia; Removal of industrial material as booty in Rumania.

The Big Three talked in circles about how to divide up the German Navy and distribute its fleets and merchant ships.

In short, Churchill not only wanted an equal distribution, but was also sympathetic to distributing a ‘fourth part’ to countries that suffered terribly during WWII – like Norway, pointing out the fact that their oil fleet was a huge part of their nation’s strength. Truman was more concerned for the time being about isolating as much of the German Navy, fleets and merchant ships as possible to the Pacific to defeat the Japanese, while Stalin just wanted as much of everything as possible as war booty.

The three leaders went back and forth for several minutes on the topic. Eventually they got to the point where Truman said,

“That seems like enough discussion. Let us proceed,” an unfortunate and recurring phrase that Truman, as Chairman of the Conference, would have to say several times during the plenary sessions.

The next topic was Spain.

This was another highly contentious debate on which everyone had his own viewpoint – that was, what to do with Franco’s government in Spain which also raised the question of what should now happen with the dictatorship in Yugoslavia. In short, Stalin wanted Franco out, while Truman was mostly in favour of just having the Big Three’s foreign secretaries come up with a plan. On the Yugoslavian front, both Truman and Churchill wanted free elections to take place while Stalin supported Tito’s dictatorship.

Conflict was waiting to erupt.

Finally, Churchill and Stalin began to argue over whether the Prime Minister’s jabs at the Soviets over Tito were “complaints” or “accusations.”

A fed up Truman, who was normally a humble Midwestern man, had reached his boiling point:

“I am here to discuss world affairs with Soviet and Great Britain governments…I’m not here to sit as a court! That is the work of San Francisco (the newly established United Nations). I want to discuss matters on which the three governments can come to an agreement!”

Stalin: “That is a correct observation.”

Churchill: “I thought that this was a matter in which the United States was very interested, particularly in view of their Yalta papers.”

Truman: “That is true. I want to see the Yalta agreement carried out.”

Stalin: “According to our information, Tito is carrying out the Crimea decisions.

Churchill: “Our paper is a repetition of what we have already said.”

Truman: “Let us drop it.”

Churchill: “It is very important.”

Truman: “We are dropping it only for the day as we did with Franco.”

Churchill: “I had hoped that we could discuss these matters frankly.”

Stalin: “But we must hear the Yugoslavs first.”

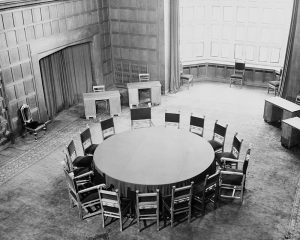

After briefly discussing the remaining items on the agenda in circles, Truman finally yielded to the stalemate and called the third session to an end – after just 45 minutes – at 4:50 PM. Only the third of 17 days into the Conference and it was already clear that the wartime spirit of cooperation was fading fast at the roundtable.

What is important to understand about the Potsdam Conference by this point is that the Big Three began facing their differences for the first time. During their previous meetings at Tehran and Yalta, which took place while they were still relying on each other to defeat Nazi Germany and liberate Hitler’s Europe, they had been able to make grand statements about the future of Germany and Europe while postponing or delegating issues on which they disagreed. Now at Potsdam, that was no longer possible.

Disagreements could no longer be concealed.

–

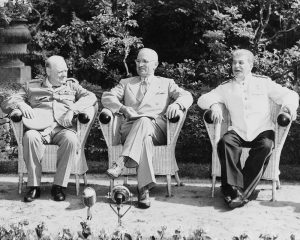

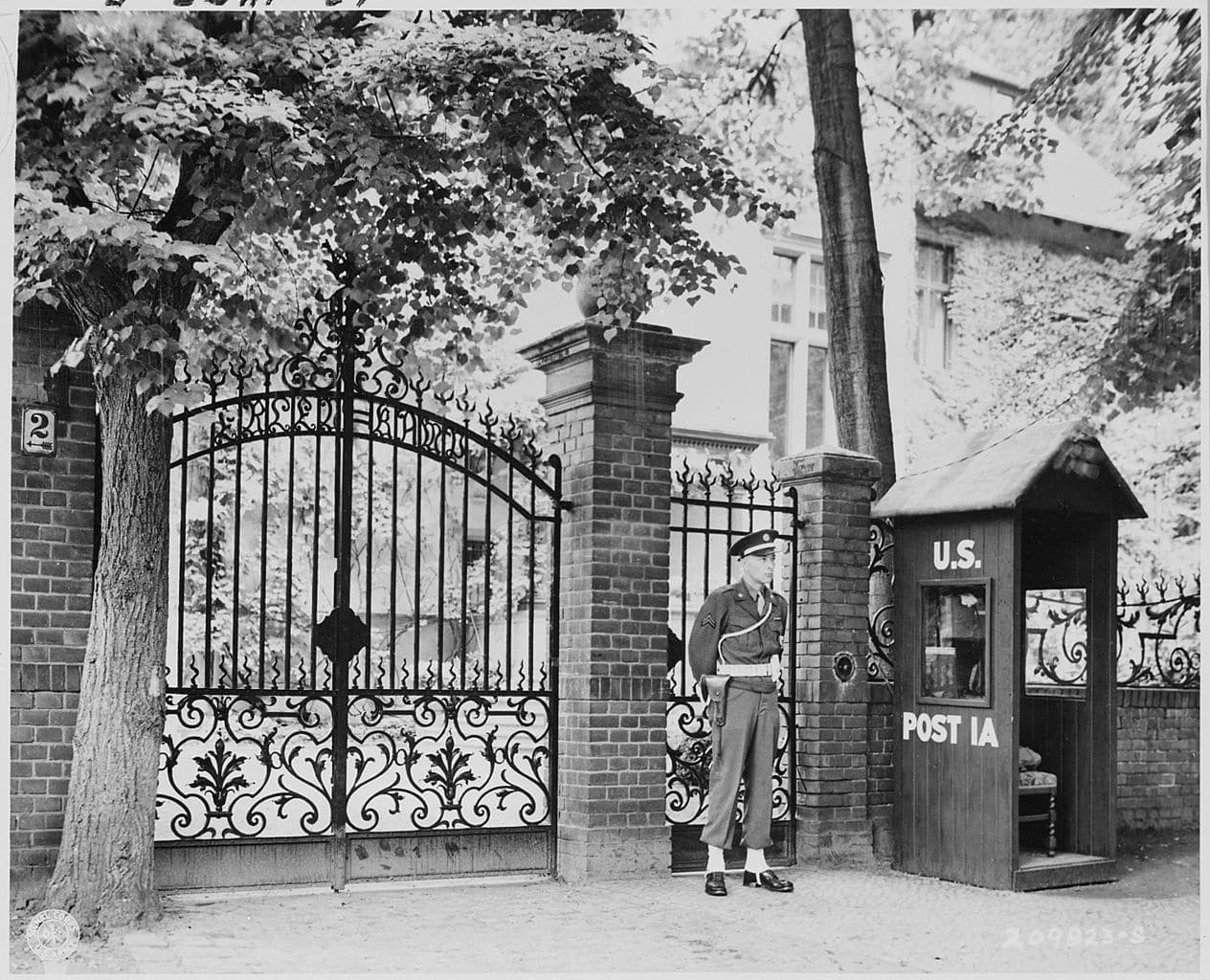

Despite their differences and the tension felt in the afternoon, it was now President Truman’s turn to host Churchill and Stalin at ‘The Little White House’ at Kaiserstraße 2. In his villa beautifully situated above lake Griebnitzsee, he threw a party that night and flew in two American GIs to entertain: twenty-seven-year-old concert pianist Sergeant Eugene List, and a professional violinist named Private First Class Stuart Canin.

Dinner that night had to have been one of the most elaborate served in Europe in years: pate de foie gras, caviar on toast, cream of tomato soup, olives, perch saute meuniere, filet mignon, mushroom gravy, shoestring potatoes, peas and carrots, tomato salad with French dressing, Roca cheese, and vanilla ice cream with chocolate sauce which had been flown in from the USS Augusta in Antwerp (Truman’s transportation across the Atlantic).

The wines included a chilled German white called Niersteiner from 1937; a fine Bordeaux, Mouton d’ Armailhac; Champagne, 1934 Pommery; plus coffee, cigars, cigarettes, port, cognac, and vodka.

“Had Churchill on my right, Stalin on my left,” Truman wrote to his wife in a letter the next day.

Churchill even toasted his political opponent, Clement Attlee, sitting quietly across the table: “I raise my glass to the leader of His Majesty’s loyal opposition.”

Churchill’s icy sarcasm was not lost on Attlee, who had thus far said very little at Potsdam.

Even Secretary of State Jimmy Byrnes was in unusually good form.

“His stories were good, and told with both Irish and southern charm,” remarked one ambassador present.

Meanwhile, Admiral Leahy got his chops busted from the others for his abstinence from alcohol.

But the most memorable part of the evening came when List and Canin made their way to the back porch overlooking lake Griebnitzsee to entertain under the lingering light of the warm July night. The two musicians, both in uniform, had been flown in from Paris at Truman’s request, and Sergeant List’s performance of the Frédéric Chopin Waltz in A Minor, Opus 42, was the highlight of the performance. Truman had asked for it specifically, but List did not know the piece nor did he have time to learn it. Later, in a letter to his wife, he described what happened when he asked if someone from the audience would be kind enough to turn the pages of music for him.

A young captain in the party started toward the piano mumbling something about not knowing how to read music but that he would take a stab at it if I would tell him when to turn. Whereupon…the President waved him aside with a sweeping gesture and volunteered to do the job himself! Just imagine! Well, you could have knocked me over with a toothpick! Thank goodness I was able to get through the waltz in a creditable, if not sensational manner, despite the general excitement and the completely unexpected appearance of President Truman in the role of page-turner. Imagine having the President of the United States turn pages for you!…But that’s the kind of man the President is.”

Stalin was charmed and Truman was delighted to see him so obviously enjoying himself.

“The old man loves music,” he wrote in that same letter to his wife. “Our boy was good.”

Food, music and booze had come to save the day, and the cold conspicuous glares of rigorous diplomacy in Cecilienhof during the day gave way to many genuine smiles on that warm summer night.

**

Our Related Tours

To learn more about Potsdam and visit the site of the Potsdam Conference, have a look at our Glory Of Prussia tours.

To learn more about the history of Cold War Berlin and life behind the Iron Curtain; have a look at our Republic Of Fear tours.

Bibliography

Byrnes, James (1947). Speaking Frankly. New York: Harper & Brothers. ISBN 978-0-837-17480-8

Cullough, David (1992). Truman. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-86920-5

Fabian, Nadine. “Ein Besuch in der Stalin-Villa in Potsdam.” Märkische Allgemeine. 23 August 2017, https://www.maz-online.de/Lokales/Potsdam/Ein-Besuch-in-der-Stalin-Villa-in-Potsdam

Neiberg, Michael (2015). Potsdam: The End of World War II and the Remaking of Europe. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-07525-6

McBaime, Albert (2017). The Accidental President. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0-544-61734-6

Miscamble, Wilson D (1978). Anthony Eden and the Truman-Molotov Conversations, April 1945

Roberts, Geoffrey (2007). Stalin at the Tehran, Yalta, and Potsdam Conferences

Smyser, William (1999). From Yalta To Berlin: The Cold War Struggle Over Germany. New York: St. Martin’s Press. ISBN 0-312-06605-8

Sternberg, Jan. “Churchill und die lila Plüschmöbel.” Märkische Allgemeine. 13 July 2015, https://www.maz-online.de/Thema/Specials/P/Potsdamer-Konferenz/Villa-Urbig-am-Griebnitzsee.

Truman, Harry S. (1956). Memoirs: Year of Decisions Volume 1. New York: Doubleday.