At 3:30pm, Secretary of War Henry Stimson arrived at the ‘Little White House’ with a full description of the test of the atomic bomb that had taken place five days earlier on July 16th. It was sent to Babelsberg by U.S. Army Brigadier General Leslie Groves, who was overseeing the Manhattan Project back in the United States and regularly updating Stimson on developments while he was with the President at Potsdam.

Behind closed doors in Truman’s villa, Stimson read Grove’s document out loud to the President and Secretary Byrnes. It took some time, as it was fourteen pages double-spaced.

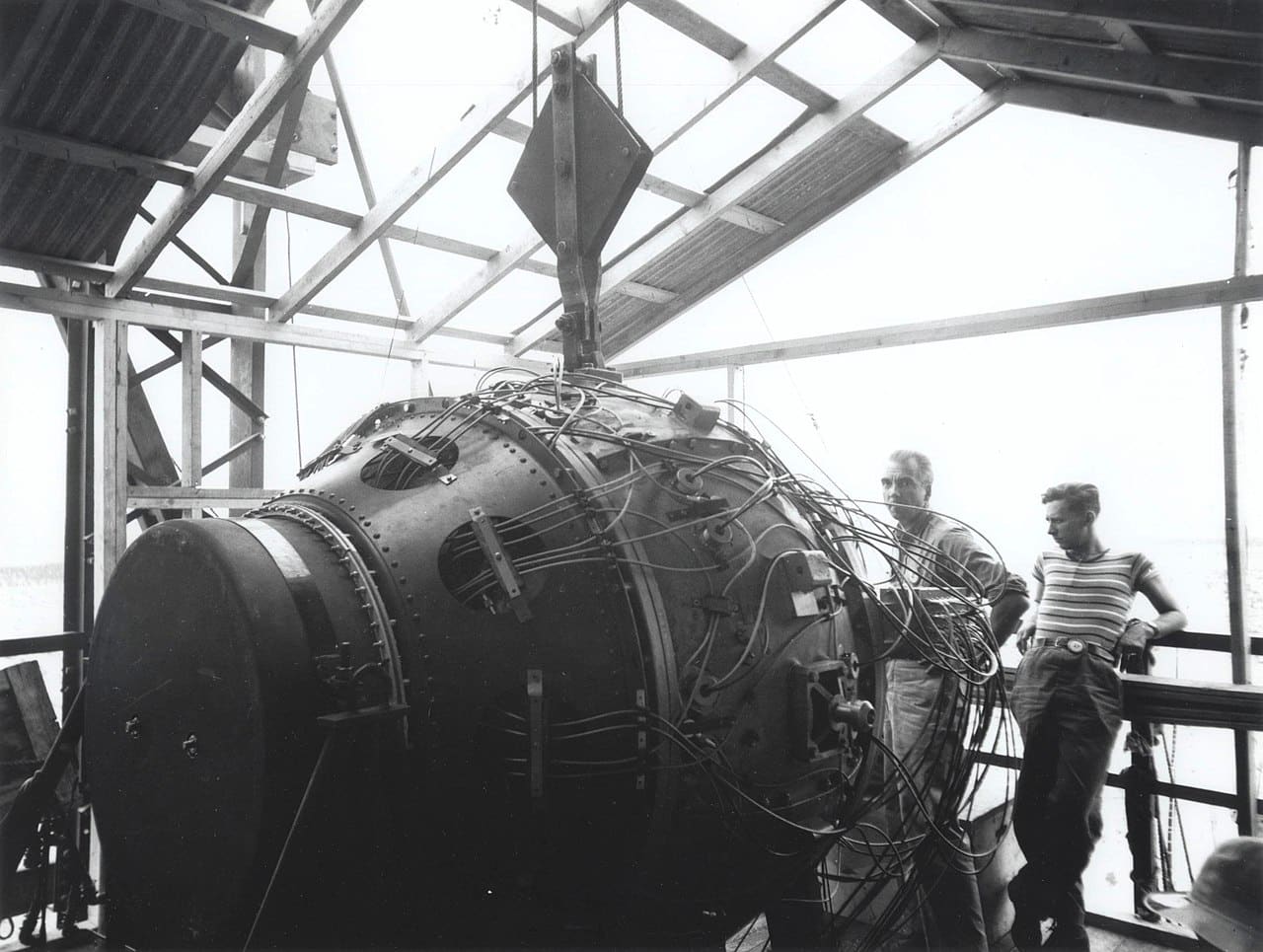

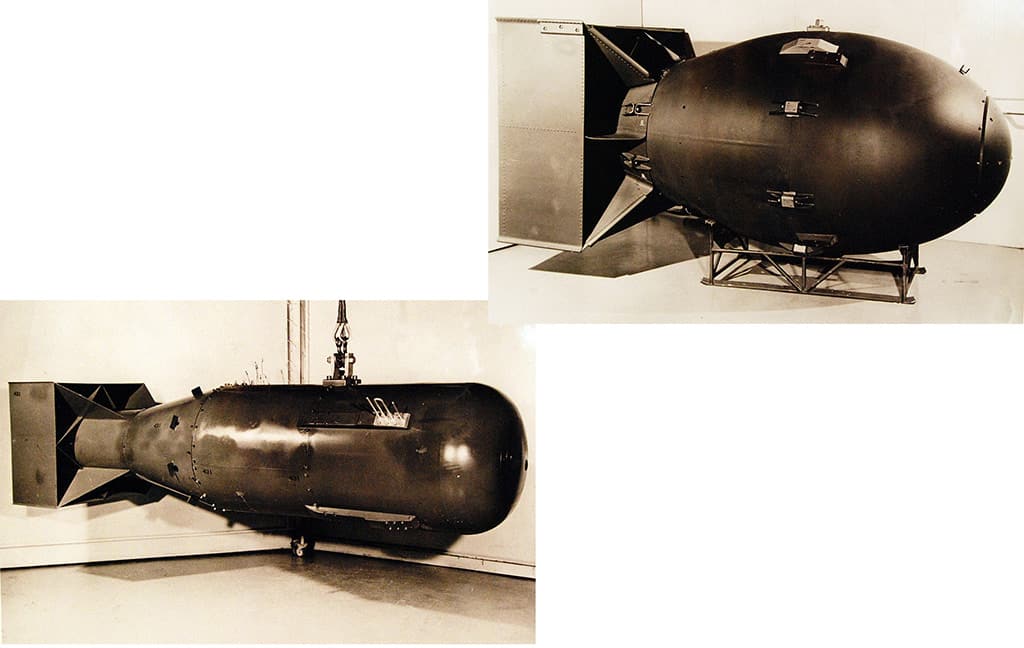

At 530, 16 July 1945, in a remote section of the Alamogordo Air Base, New Mexico, the first full scale test was made of the implosion type atomic fission bomb. For the first time in history there was a nuclear explosion. The test was successful beyond the most optimistic expectations of anyone. Based on the data which it has been possible to work up to date, I estimate the energy generated to be in excess of the equivalent of 15,000 to 20,000 tons of TNT.

Grove’s description would go on to note that windows were shattered by the blast as far off as 125 miles from ground zero. The 60 foot high steel tower, from which the bomb fell, immediately evaporated. It left a crater in the New Mexico desert more than two miles wide. It knocked down men more than 10,000 yards away and the mushroom cloud, containing a huge concentration of radioactive material, could be seen from more than 200 miles away.

After reading the document, Stimson looked up at the President to see that he was “tremendously pepped up by it,” as he would record in his diary. He went on to write:

“He (Truman) said it gave him an entirely new feeling of confidence and he thanked me for having come to the Conference and being present to help him in this way.”

On the topic of the Manhattan Project, the relationship between Truman and Stimson – and even Byrnes for that matter – had come a long way since its somewhat awkward start a couple of years before.

When Truman was still in the Senate in 1943, he chaired a committee that was investigating defense and war production spending after several reports of mismanagement, inefficiencies and unlawful profiteering had surfaced. During his investigation, Truman inadvertently came across some information about a secret plant being built in Pasco, Washington that – unknown to him at the time – was tied to the Manhattan Project. He may not have thought anything of it and perhaps just dismissed his findings, but this was not the first piece of information about a secret plant of which he had learned. Not long before, his committee had also discovered a secret plant in Minnesota and quickly came to realize that both had been built for similar purposes. After Truman’s committee sent an inquiry to Stimson’s office to find out what was going on, the Secretary of War immediately got in touch with the Senator to nip his investigation in the bud before it spilled the beans on disclosing one of the biggest military secrets in world history.

On June 17, 1943, Stimson got on the phone with Truman to politely steer him away from his findings:

Stimson: “…I think I’ve had a letter from Mr. Hally, I think who is an assistant of Mr. Fulton of your office.”

Truman: “That’s right.”

Stimson: “In connection with the plant at Pasco, Washington.”

Truman: “That’s right.”

Stimson: “Now that’s a matter which I know all about personally, and I am one of the group of two or three men in the whole world who know about it.”

Truman: “I see.”

Stimson: “It’s part of a very important secret development.”

Truman: “Well, all right then…I herewith see the situation, Mr. Secretary, and you won’t have to say another word to me. Whenever you say that to me, that’s all I want to hear.”

Stimson: “All right.”

Toward the end of the conversation and after Truman explained that the connection between the plants in Washington and Minnesota was the cause for which they inquired into the matter, he told Stimson that if it is indeed for a specific purpose then that was all he needed to know.

The Secretary replied by saying:

“Not only for a specific purpose, but a unique purpose.”

The fact that a junior United States Senator was not informed about a top secret project being developed in the War Department is not surprising; what is a bit unexpected, however, is the fact that Truman was never informed or at the very least vaguely briefed about the project during his entire 82 days as vice-president. During this time, he had met just twice with Roosevelt, mostly making small talk, posing for photographers, and discussing nothing of importance. Roosevelt confided nothing to Truman – rarely anyone for that matter – nor did he keep him updated on wartime policy.

Therefore, after his first cabinet meeting upon assuming the Office of the Presidency, Stimson approached Truman to inform him about the top secret development that he and his committee had poked at a couple of years before.

This would be the first time that the new President of the United States would hear of the nearly five-year-old atomic project.

Truman described the scene in his memoir years later:

“That first cabinet meeting was short, and when it adjourned, the members rose silently and made their way from the room–except for Secretary Stimson.

He asked to speak to me about a most urgent matter. Stimson told me that he wanted me to know about an immense project that was underway–a project looking to the development of a new explosive of almost unbelievable destructive power. That was all he felt free to say at the time, and his statement left me puzzled. It was the first bit of information that had come to me about the atomic bomb, but he gave me no details…The next day Jimmy Byrnes, who until shortly before had been Director of War Mobilization for President Roosevelt, came to see me, and even he told me a few details, though with great solemnity he said that we were perfecting an explosive great enough to destroy the whole world.”

At a much more extensive meeting at the White House a few weeks later, Stimson gave Truman a memorandum projecting that the bomb would be ready for use within four months and he also suggested to the President that a committee be created to review the options for its possible use. Truman agreed and named Stimson to chair what would become known as the Interim Committee. The committee, along with Byrnes, eventually recommended and ultimately urged the President to use the bomb – without warning – just as soon as it was ready.

If the bomb could prevent a land mass invasion and save American lives, then it was felt among the committee that it had to be used. They saw it as necessary.

Despite this recommendation, debate would continue within the government, as well as among the scientists working on the bomb’s development, over the moral and military issues relating to its use.

Yet by this point, Truman, Stimson and Byrnes must have felt a deep sense of relief that so much time and effort – not to mention the tremendous amount of money that had been pumped into the project for so many years – had not been wasted.

As Truman biographer David McCullough would write:

“It was not just that $2 billion had been spent, but that it was $2 billion that could have been used for the war effort in other ways. The thing worked – it could end the war – and, there was the pride too that a task of such complexity and magnitude, so completely unprecedented, had been an American success.”

–

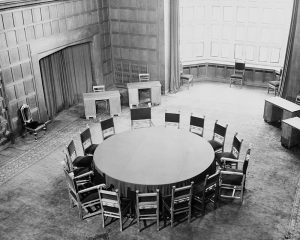

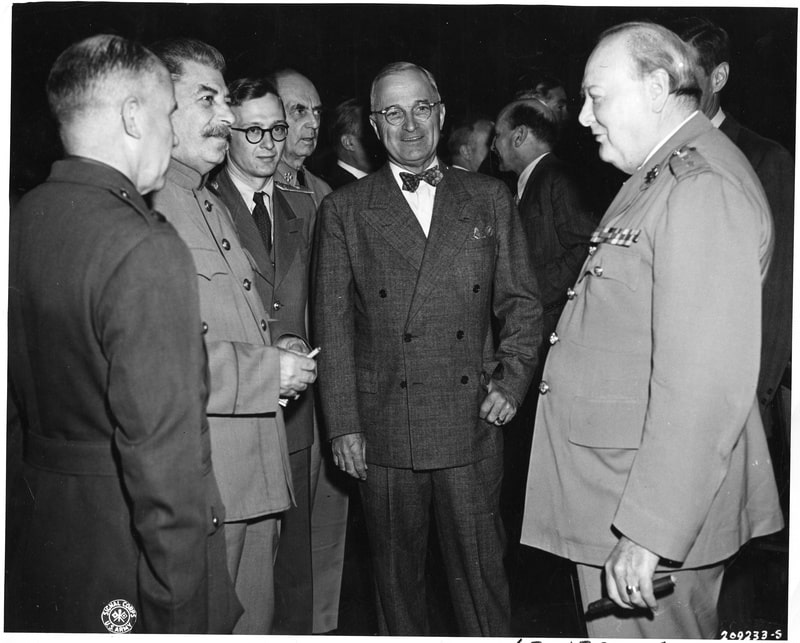

Truman went straight to Cecilienhof after the meeting where the fifth plenary session was called to order at 5:05pm.

According to Robert Murphy, a political advisor to General Eisenhower:

“The change in Truman was pronounced. He was surer of himself, more assertive. It was apparent something had happened. Churchill later told Stimson he could not imagine what had come over the President.”

Churchill would find out what had come over Truman the next day when Stimson went to see the Prime Minister to read Grove’s report.

Clearly Truman was fortified by the news and it is hard to imagine that he would not have been. The notion that he and Byrnes felt that their hand might be thus strengthened at the bargaining table with the Soviets in time to come is perfectly understandable, but by no means was this the primary consideration as some would later contend.

The Polish question would dominate this plenary session and set up endless debate on what would prove to be a thorny topic all the way to the end of the Conference.

In vague language at Yalta it had been agreed that Poland would get territory from Germany to the west to compensate what Russia had taken from Poland in the east. At the moment, however, the Red Army was occupying all of Polish territory from Germany’s 1937 border in the east all the way up to the Soviet zone of occupation in Germany in the west. Furthermore, a Soviet backed, Polish Administrative Area had already been established to run the area.

Truman: The question is not who occupies the country, but how we stand on the question as to who is to occupy Germany. I want it understood that the Soviet [Union] is occupying this zone and is responsible for it. I don’t think we are far apart on our conclusions.

Stalin: On paper it is formerly German territory but in fact it is Polish territory. There are no Germans left. The Soviet [Union] is responsible for the territory.

Truman: Where are the nine million Germans?

Stalin: They have fled.

Churchill: How can they be fed? I am told that under the Polish plan put forward by the Soviets that a quarter of arable land of Germany would be alienated—one-fourth of all the arable land from which German food and reparations must come. The Poles come from the East, but 8¼ million Germans are displaced? It is apparent that a disproportionate part of the population will be cast on the rest of Germany with its food supplies alienated.

Truman: I propose that the matters of the Polish frontier be considered at the peace conference after consultation with the Polish government of national unity. We decided that Germany with 1937 boundaries should be considered a starting point. We decided on our zones. We moved our troops to the zones assigned to us. Now another occupying government has been assigned a zone without consultation with us. We can not arrive at reparations and other problems of Germany if Germany is divided up before the peace conference. I am very friendly to Poland and sympathetic with what Russia proposes regarding the western frontier, but I do not want to do it that way.

In other words, the Soviets could not arbitrarily dictate how things were to be, and there would be no progress on reparations or other matters concerning Germany until this was understood.

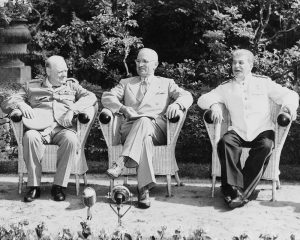

The Big Three once again tabled the question of Poland for further discussion and adjourned.

Truman had shown an unexpected amount of energy and confidence during this session. Churchill was pleased and his Foreign Secretary, Anthony Eden, thought it was Truman’s best day so far. Even William Leahy, the President’s Chief of Staff, was impressed, though he was certain – bomb or no bomb – that Stalin had no intention of changing his course in Eastern Europe. He regarded Poland as a ‘Soviet fait accompli’ and since millions of Soviet soldiers occupied the territory to the east, there was little the United States and Great Britain could do about it, short of going to war. This of course was unthinkable.

The time had come for Stalin to host the American and British delegations for an evening party at his villa. Here, there was no trace of the heated tension over Poland from just a couple of hours ago. Stalin wanted to outdo the Americans in a contest of decadence and It is safe to say that he succeeded. Tonight would end up being the best time the President would have during his entire 19 days at Potsdam.

“It started with caviar and vodka…” he wrote in a letter to his daughter, Margaret.

“Then smoked herring, then white fish and vegetables, then venison and vegetables, then duck and chicken and finally two desserts, ice cream and strawberries and a wind-up of sliced watermelon. White wine, red wine, champagne and cognac in liberal quantities…Stalin also sent to Moscow and brought his two best pianists and two feminine violinists. They were excellent. Played Chopin, Liszt, Tchaikovsky and all the rest.”

Churchill, on the other hand, told Truman he was bored to tears and wanted to head home early. Truman told the Prime Minister that he was enjoying himself and that he had planned to stay until the party was over. So, Churchill begrudgingly changed his mind and slowly made his way over to a corner for another half hour or so. Until the music ended, he “glowered, growled, and grumbled,” as Truman would amusingly describe it.

At one point Truman even asked Stalin, who was also known as the ‘Man of Steel’, how he could drink so much vodka. Through an interpreter, Stalin said:

“Tell the president it is French wine, because since my heart attack, I can’t drink the way I used to.”

**

Our Related Tours

To learn more about Potsdam and visit the site of the Potsdam Conference, have a look at our Glory Of Prussia tours.

To learn more about the history of Cold War Berlin and life behind the Iron Curtain; have a look at our Republic Of Fear tours.

Bibliography

Byrnes, James (1947). Speaking Frankly. New York: Harper & Brothers. ISBN 978-0-837-17480-8

Cullough, David (1992). Truman. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-86920-5

Fabian, Nadine. “Ein Besuch in der Stalin-Villa in Potsdam.” Märkische Allgemeine. 23 August 2017, https://www.maz-online.de/Lokales/Potsdam/Ein-Besuch-in-der-Stalin-Villa-in-Potsdam

Neiberg, Michael (2015). Potsdam: The End of World War II and the Remaking of Europe. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-07525-6

McBaime, Albert (2017). The Accidental President. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0-544-61734-6

Miscamble, Wilson D (1978). Anthony Eden and the Truman-Molotov Conversations, April 1945

Roberts, Geoffrey (2007). Stalin at the Tehran, Yalta, and Potsdam Conferences

Smyser, William (1999). From Yalta To Berlin: The Cold War Struggle Over Germany. New York: St. Martin’s Press. ISBN 0-312-06605-8

Sternberg, Jan. “Churchill und die lila Plüschmöbel.” Märkische Allgemeine. 13 July 2015, https://www.maz-online.de/Thema/Specials/P/Potsdamer-Konferenz/Villa-Urbig-am-Griebnitzsee.

Truman, Harry S. (1956). Memoirs: Year of Decisions Volume 1. New York: Doubleday.