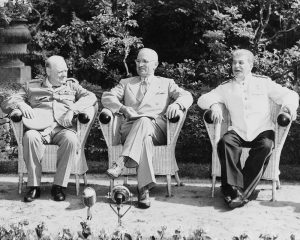

Shortly after the Battle of Berlin and the unconditional surrender of Nazi Germany in May 1945, Joseph Stalin of the Soviet Union, Harry S. Truman of the United States and Winston Churchill of Great Britain would meet near the former Nazi capital to discuss what to do with a defeated Germany, Allied strategy in the Pacific Theater, and other issues confronting the postwar world.

This was to be the final war-time meeting between the Big Three powers of the Anti-Hitler Coalition; following previous meetings in Tehran and Yalta.

Originally called ‘The Berlin Conference’ it would become more popularly known as the Potsdam Conference; after it was decided to move the summit southwest of Berlin to the German city of Potsdam and the Cecilienhof Palace – a former resident of the royal House of Hohenzollern.

The discussions, agreements, and confrontations that would take place here over the space of 17 days would decide the fate of Europe and set the stage for the coming Cold War. Ensuring the division of Germany for the next 45 years, and creating the conditions for the greatest ideological confrontation of the 20th century – between East and West.

(Special thanks to Jim McDonough of the Berlin Guides Association for expertly compiling this account of the proceedings)

–

On January 6, 1945, a tired and frail President Franklin D. Roosevelt gave what would be his last State of the Union Address to the 79th United States Congress.

As Anglo-American-Soviet forces were closing in on Berlin, the President sent out a message warning the nations around the globe that the peace of the world can only be made and kept if countries are willing to respect, tolerate, and understand one another’s opinions and feelings.

“The nearer we come to vanquishing our enemies the more we inevitably become conscious of differences among the victors. We must not let those differences divide us and blind us to our more important common and continuing interests in winning the war and building peace. International cooperation on which enduring peace must be based is not a one-way street.”

Roosevelt could sense that Hitler’s “Thousand Year Reich” was crumbling rapidly and he knew that further decisions between his allies and him about military strategy would no longer be necessary. Instead, the leaders of the victorious nations would soon have to sit down to present their agendas, give their opinions, and make political decisions in a collective attempt to secure a lasting peace in a world without Hitler and the Nazis.

The leaders of the so-called Grand Alliance or anti-Hitler coalition, UK Prime Minister Winston Churchill, Soviet leader Joseph Stalin and Roosevelt himself, knew as early as 1943 that their forces were collectively winning the war against the Nazis, but they also knew that the only way that victory could be achieved was if their alliance remained united.

Therefore, the Big Three met for the first time at the Tehran Conference in Tehran, Iran from November 28th – December 1st 1943. It was here that they began to coordinate their military strategy in the European and Pacific theaters, as well as discuss a number of important decisions concerning the post WWII world. Moreover, it was a summit that displayed a show of unity to the rest of the world that the Grand Alliance was committed to defeating fascism in order to secure a future peace throughout the globe.

As Allied armies moved closer to Berlin, Churchill, Roosevelt and Stalin met for their second summit in the Crimea from February 4th until February 11th 1945. The key points on the agenda at the so-called Yalta Conference were issues related to military tactics in the Pacific Theater and postwar politics in Europe. Unlike Tehran, the meeting did not dwell on military matters, but Stalin did pledge to join the war against Japan three months after the end of the war in Europe. The three leaders discussed the postwar treatment of Germany on numerous occasions throughout the summit: ultimately agreeing that it should be divided into four occupation zones (involving the French) and that it should pay vast reparations, although when and how those reparations were to be paid was something the leaders left alone for the time being.

Furthermore, the future of Poland would dominate much of the discussion at Yalta as it would months later at Potsdam. The Big Three agreed for the time that Poland’s western frontier would have to be revisited after the war was over, but that ‘considerable’ territorial compensation from Germany should be made. Stalin also pledged to permit free and democratic elections and support a so-called “Provisional Government of National Unity” that would be made up of the Polish government in exile in London and the Communist Lublin Committee.

The Big Three left Yalta after addressing several contentious issues that ultimately disclosed some of their differences that were beginning to bud.

The fact that they were not able to decide, but rather temporarily agree, on major issues like reparations and borders east of Germany, meant that a third meeting would have to be held once the Nazi beast had been defeated.

In the summer of 1945 things looked much different than they had when the Yalta Conference took place just months before. Germany had accepted unconditional surrender on May 8th/9th bringing hostilities to an end, Allied armies occupied much of central and eastern Europe, and Churchill and Stalin were corresponding with a new Commander in Chief of the United States.

–

Late in the afternoon of April 12, 1945, Vice President of the United States Harry S. Truman was sitting in Speaker of the House Sam Rayburn’s office in the U.S. Capitol sipping on Bourbon with some old friends from Congress.

This common afternoon affair was interrupted on this day by a telephone call from White House Press Secretary Steve Early who wished to speak with Truman. Early told Truman to ‘quickly and quietly’ make his way to the White House. “Jesus Christ and General Jackson,” Truman exclaimed before he excused himself, hurried through the Capitol, and got into a car that sped him down Constitutional Avenue and to the main White House entrance where Mrs. Roosevelt was waiting for him inside.

“Harry, the President is dead,” said Mrs. Roosevelt as she put her hand on his shoulder to break the somber news to him. Truman immediately asked if there was anything that he could do for her. “Is there anything that we can do for you,” she famously replied. “For you are the one in trouble now.”

Vice President for just 82 days – whose resume to Washington had featured a high school diploma as the highest level of completed education and recent work experience that included running a farm and then an insolvent haberdashery – Harry Truman was all at once catapulted into the office of the President of the United States.

He was now a wartime Commander in Chief of 16 million men that were spread out across Europe and Asia and leader of a country that possessed one of the most terrifying war arsenals on earth.

Across the pond in London, Prime Minister Winston Churchill had lost a counterpart in the struggle against defeating fascism and militarism in Europe and Japan. He had also lost a close, personal friend. Yet whoever the new American president was, Churchill knew that he would have to work side by side with him to tackle the most pressing issues confronting the postwar world after victory was achieved.

One issue that Churchill seemed to be perturbed about was the postwar intentions of the Soviet Union. He could see that the wartime spirit of cooperation was fading before his eyes as the Red Army now occupied large parts of eastern and central Europe. In a letter to Truman on May 12, 1945 he expressed his skepticism to the President and said that he was “profoundly concerned about the European situation” and was worried about a premature withdrawal of American armed forces from Europe. He went on to write:

“…What is to happen about Russia? I have always worked for friendship with Russia, but like you, I feel deep anxiety because of their misinterpretation of the Yalta decisions, their attitude towards Poland, their overwhelming influence in the Balkans…,the difficulties they make about Vienna, the combination of Russian power and the territories under their control or occupied, coupled with the Communist technique in so many other countries, and above all their power to maintain very large armies in the field for a long time.”

A week earlier, around the same time that Germany was surrendering, Churchill wrote to Truman about setting up a meeting between the three heads of governments.

He felt that matters could no longer be carried out by correspondence and that it was time for a third wartime summit between the Grand Alliance to take place. He also urged Truman to delay his withdrawal of American forces from what was now considered the Soviet occupation zone as agreed upon at Yalta, and to use their occupying position as equity before negotiating with Stalin. Although Truman acknowledged that there should be a meeting involving the heads of government, he also made it clear that it was his position to adhere to the American interpretation of the Yalta agreements, which meant that American forces would soon be leaving the areas they had conquered in what was now the Soviet zone. Some might call this a blunder in hindsight, but Truman, the new guy on the job, most likely did not want to be accused of misinterpreting the Yalta agreements from what Roosevelt had negotiated.

Churchill hoped to meet as soon as possible and wanted the summit to take place around mid-June. He knew that every minute mattered and felt that the Soviets might play for time in order to continue exerting presence in the countries they currently occupied to achieve a kind of permanent political and economic gain. In a letter to Truman on May 11, 1945, he wrote:

“Mr. President, in these next two months the gravest matters of the world will be decided.”

Truman further agreed that a meeting was necessary for the US and Great Britain to come to an understanding with the Soviet Union, but he also felt that Stalin should be the one to propose such a summit as to avoid any suspicion of an Anglo-American gang up on the Soviets. There had already been a few instances that gave the Soviets the right to be pessimistic about working with the Americans in the future. Events like the tumultuous, heated exchange between Truman and Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov at the White House in April, the Soviets finding out that the U.S. had secretly met with German representatives in Bern, Switzerland in March to negotiate a separate unconditional surrender, and Truman’s temporary halt on the Lend-Lease to Russia shortly after Nazi Germany had capitulated, all gave the Soviets reasons to believe that America and its new president could not be trusted. Yet, America was still optimistic that they could just work out any problems and smooth over any rifts if they could just sit down at the same table and talk about the future.

In a meeting with Stalin on May 26, 1945, Harry Hopkins, a special adviser and assistant to President Truman who was assigned to dealing with the Soviet Union during WWII, steered the conversation toward the topic of a tripartite meeting. The Soviet dictator was actually much in favor of this and told Hopkins that the question was “ripe and knocking on the door” when it came to the question of setting up a peace conference to settle WWII in Europe; but, he also made it clear that it would be wise to select a time and place so that proper preparations could be made. Moreover, Stalin was eager to meet Truman and Churchill and eventually suggested that there would be adequate quarters for such a meeting in the suburbs of Berlin. Truman then sent a letter to Churchill on May 28th stating:

“Stalin has informed me through Mr. Hopkins that he would like to have our three party meeting in the Berlin area and I will reply that I have no objection to the Berlin area.”

After Churchill made a final attempt to push for a June 15th start – and following a couple short correspondences from Stalin who eventually indicated that meeting on June 15th was just as arbitrary as meeting on July 15th – Truman ultimately had the final say and made it clear that he could not meet before June 30th as this date marked the end of the fiscal year, something for which he felt that he ‘must’ be in Washington.

In a letter to Churchill on June 1st, Truman wrote:

“Marshal Stalin has informed me that he is agreeable to having our forthcoming meeting in the vicinity of Berlin about July fifteenth, which date also seems to be possible from the point of view of my domestic duties. I am looking forward with pleasure to seeing you at that time and with confidence that the meeting will produce results of great value to the future of our world.”

Although this very well could have been true, pushing the meeting as far back as he could bought him time – that is, time to study and time to get caught up on American foreign affairs. Unlike his predecessor Roosevelt – who acted on intuition and accumulated knowledge – Truman read his briefs and studied his subjects at hand very carefully. He would eventually prepare himself for this forthcoming meeting much more thoroughly than Roosevelt had prepared himself for Tehran or Yalta.

–

The wheels were now set in motion for the leaders of the Grand Alliance to attend a third wartime summit which would officially be known as the ‘Three Power Conference of Berlin’.

In a letter exchange between Stalin and Churchill on May 29th, Churchill humorously replied that he would be glad to meet Stalin and Truman in “what was left of Berlin” alluding to the damage and destruction that had occurred in the German capital during WWII. As Stalin was adamant to meet in Berlin and was essentially not in favor of discussing an alternative site, the Soviets would take it upon themselves to survey the area and choose a location that would adequately suit a site for such a summit to take place at. With much of Berlin in ruin, however, the Soviets headed southwest assessing possible sites and eventually made their way across the river Havel and into the historic neighboring city of Potsdam.

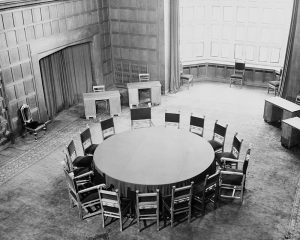

In a conversation between the U.S. Ambassador to Russia, Averell Harriman, and top Russian diplomat, Andrey Vyshinsky, on June 21st in Moscow, Harriman asked Vyshinksy for an update on what kind of arrangements the Soviet Government had in mind for the forthcoming conference. Vyshinsky stated that he could not give any definite information at the present time, but he did say that it was proposed to assign a special zone to each delegation (3 in total) in the Potsdam district of Babelsberg where they would be quartered during the summit. Finally, there would be a fourth zone, which the three delegations would share, where the conference itself would take place at: the Cecilienhof Palace on Potsdam’s northern border.

Completed in 1917, this was the final residence built by the House of Hohenzollern during its 500 years of dynastic rule in Brandenburg. It was named after Princess Cecilie of Mecklenburg-Schwerin who was the wife of the last Crown Prince of Prussia, Prince Wilhelm (who would have become King of Prussia and German Emperor if Germany had not surrendered at the end of WWI). Unlike most of the Hohenzollern palaces in Berlin and Brandenburg – like the Charlottenburg Palace in Berlin and the famous Sanssouci Palace in Potsdam – Cecilienhof’s early history was made while the head of the House of Hohenzollern (Wilhelm) lived a private and secluded life without monarchical duties or commitments. Unfortunately for this former royal family, they would abandon the palace before the Soviet advance on the area at the end of WWII and thus leave behind their new jewel residence for the Soviets to eventually occupy.

Taken by units of Ivan Konev’s 1st Ukrainian Front during the Battle of Berlin, the Soviets had in their possession a place that could provide ample space and modern amenities; and most importantly, they saw Cecilienhof’s lakeside seclusion on the grounds of Potsdam’s Neuer Garten Park could fulfill the requirements needed to protect the three most powerful men on earth.

And so for the next 17 days, Cecilienhof would serve as the historic site where The Big Three would argue over borders, reparations, and the future of the postwar world – all of which would eventually lead to a literal and ideological division that would last for almost half a century.

**

Our Related Tours

To learn more about Potsdam and visit the site of the Potsdam Conference, have a look at our Royal Potsdam tours.

To learn more about the history of Cold War Berlin and life behind the Iron Curtain; have a look at our Republic Of Fear tours.

Bibliography

Byrnes, James (1947). Speaking Frankly. New York: Harper & Brothers. ISBN 978-0-837-17480-8

Cullough, David (1992). Truman. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-86920-5

Fabian, Nadine. “Ein Besuch in der Stalin-Villa in Potsdam.” Märkische Allgemeine. 23 August 2017, https://www.maz-online.de/Lokales/Potsdam/Ein-Besuch-in-der-Stalin-Villa-in-Potsdam

Neiberg, Michael (2015). Potsdam: The End of World War II and the Remaking of Europe. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-07525-6

McBaime, Albert (2017). The Accidental President. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0-544-61734-6

Miscamble, Wilson D (1978). Anthony Eden and the Truman-Molotov Conversations, April 1945

Roberts, Geoffrey (2007). Stalin at the Tehran, Yalta, and Potsdam Conferences

Smyser, William (1999). From Yalta To Berlin: The Cold War Struggle Over Germany. New York: St. Martin’s Press. ISBN 0-312-06605-8

Sternberg, Jan. “Churchill und die lila Plüschmöbel.” Märkische Allgemeine. 13 July 2015, https://www.maz-online.de/Thema/Specials/P/Potsdamer-Konferenz/Villa-Urbig-am-Griebnitzsee.

Truman, Harry S. (1956). Memoirs: Year of Decisions Volume 1. New York: Doubleday.