In 1919, the Italian Foreign Minister, Sidney Sonnino, expressed his anger with Woodrow Wilson, shouting, “Is it possible to change the world from a room, through the actions of some diplomats? Go to the Balkans and try an experiment with the Fourteen Points.”

Like most of his fellow European diplomats, Sonnino was irritated with American ideals and frustrated by the lack of real power the United States put behind its principles. Despite its wealth and its post World War I food relief program that likely saved millions of Europeans from starvation, there was a limit on what America could and would do. Soon, it would leave Europe, head back to its own shores, giving many Europeans reasons to criticize America both for the failure to back up its ideals and its unwillingness to pay the price required of the great power it now thought it had become.

The end of World War II threatened a repetition of that same gap between ideals and actions.

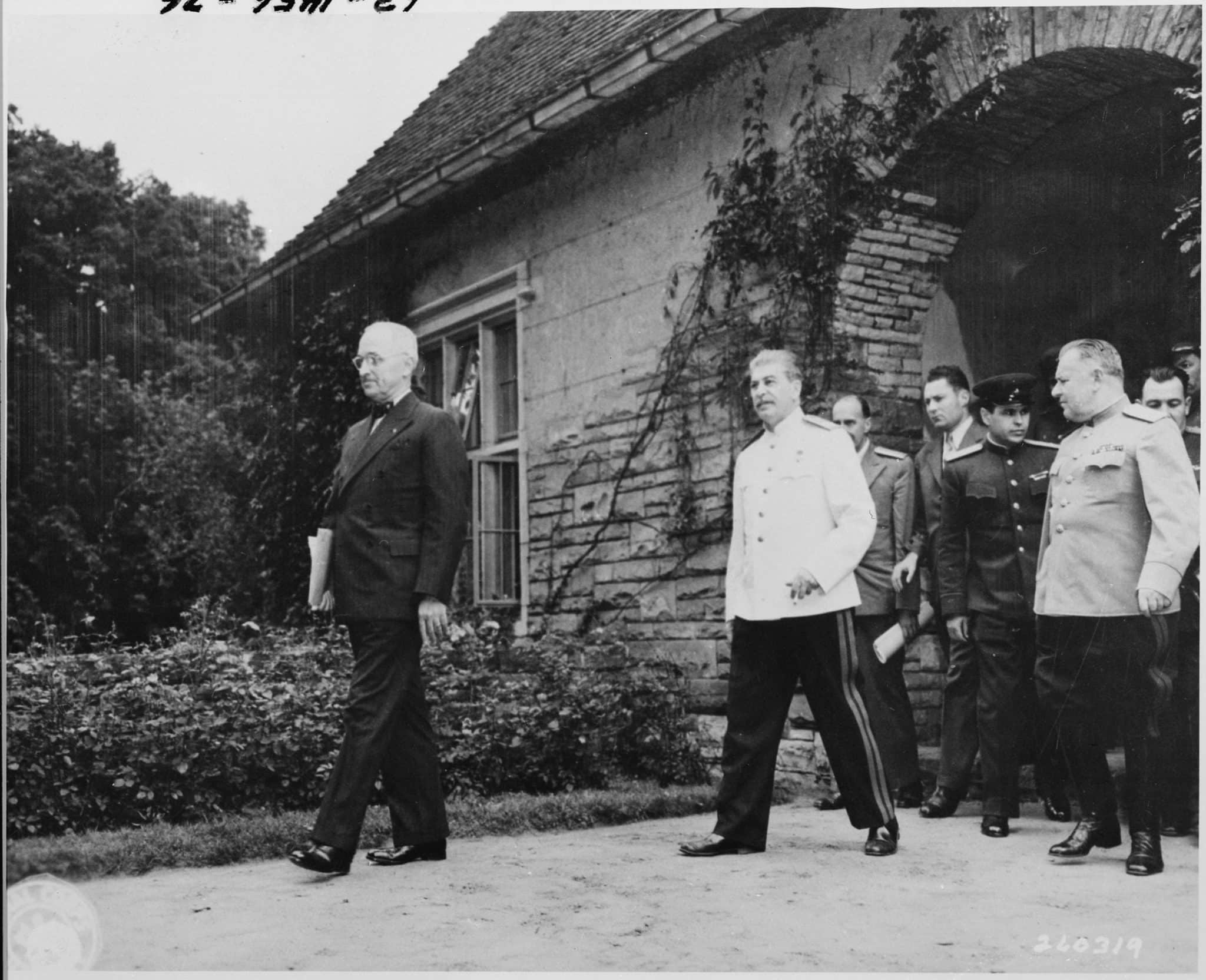

The American leaders of 1945 hoped to use their power with the British and the Soviets to reshape Europe, largely predicated on their own image – that was, a democratic Europe with markets open to global trade that would provide the necessary foundation for a future of stability and peace.

Despite the fact that they knew that their goals would not always line up with those of the Soviets – or even the British and French for that matter – the American delegation did not leave Potsdam thinking that a future of conflict with the Russians was either inevitable or even likely.

Although some insiders predicted a future of increased East-West conflict – like British Prime Minister Clement Attlee and American diplomat George Keenan, who served as deputy head of the mission to Moscow – more people came out of Potsdam optimistic rather than pessimistic.

Truman thought that the years after 1945 would feature widely expanded American trade with the Soviet Union and the redevelopment of Germany as a single economic and political unit. Jimmy Byrnes also believed that dividing Germany for the purposes of reparations ensured a future of cooperation, not conflict, with the Soviets by removing monetary reparations as a potential area of friction and instability.

He left Potsdam optimistic about the future of US-Soviet relations, even though he knew that several areas of disagreement remained.

At that time, Byrnes actually saw bigger problems in American relations with Great Britain, whose leaders he thought were more interested in the recovery of their empire than in doing the difficult and expensive work necessary to ensure the reconstruction of continental Europe. He had listened to Churchill allude to this on the record during the plenary sessions and witnessed him firsthand laminate the current melancholy state of Great Britain to Truman over lunch at the ‘Little White House’ on July 18, highlighting its staggering debt and declining influence in the world.

At which point, the President then tried to lift the tired and gloomy Prime Minister’s spirits by thanking the British for “holding down the fort” at the beginning of the war, otherwise the United States could very well – as Truman put it – have been fighting the Germans on the shores of America. Furthermore, Byrnes also guessed that France, Italy, and maybe even Great Britain would become difficult allies because their strategic goals did not always overlap with those of the United States’.

America’s closest and most reliable partner for peace in Europe, he presciently predicted, might turn out to be Germany, if America’s two-time enemy could somehow develop a democratic government and a functional economy.

Unfortunately, the Soviets would never let a unified Germany achieve this; only a divided Germany had a chance to.

–

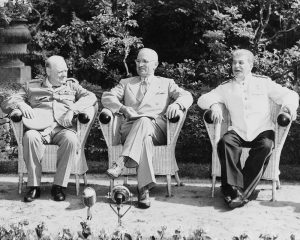

When one really thinks about it, the Potsdam Conference should have been a time of celebration. It should have been the most harmonious and most hopeful of the Big Three conferences. In short, it should have marked the start of a new era of good feeling among the Allied powers now that their common foe, Nazi Germany, had been defeated. Unfortunately, it did not turn out that way – and in practical terms, there was really no chance that it ever would.

Indeed, spirits were high at the onset of the Conference and there were even moments where smiles and laughter were shared – particularly at the dinner parties that each delegation took turns hosting – but music, food and alcohol profoundly helped create those moments which would do a fine job at smoothing over any tension and frustration felt during the day. But as the Conference rolled on and as social gatherings became a thing of the past, one day of friction and exasperation would run into the next.

The biggest problem was that the Americans, British and Soviets were finally forced to face their differences for the first time at Potsdam. During the previous conferences at Yalta and Tehran, which took place while they still needed each other to fight Hitler and defeat fascism, they had been able to make grand statements about the future of Germany and Europe while postponing or delegating issues on which they disagreed.

At the very first plenary session on July 17, Truman insisted on results, “something in the bag at the end of every day,” as Churchill observed, underscoring the whole reason why he had made the long journey to Potsdam in the first place. He wanted the future of Germany settled on terms accepted as satisfactory to all three delegations as it was German aggression that necessitated a gathering of the victorious heads of state for the second time in a matter of just two and a half decades. Both the Americans and British wanted free elections in Poland, Eastern Europe, and the Balkans and they – particularly the Americans – initially wanted the Soviet Union to join in the war against Japan as soon as possible.

Except for the latter, unfortunately, all of this faced ambiguity, delays, and frustration, with Stalin having no desire to accept any agreement that threatened the control he already had – that is, wherever the Red Army stood.

Stalin saw himself as the leader of the country that had made the ultimate sacrifice and suffered more domestic terror at the hands of the German Army than any other Allied nation during World War II; and therefore, he had already made up his mind well before his arrival in Germany that he would surrender nothing of any kind that harmed the Soviet Union’s post-war interests or threatened its post-war security when the bargaining and negotiating began.

This could very well have been predicted after the very first meeting between Stalin and Truman on July 17. At that lunch, the Generalissimo told the President that he wanted to cooperate with the United States in peace as in war.

“But in peace,” Stalin said, “…that would be more difficult…”, immediately filling the ‘Little White House’ with tension and revealing to those who had been around since the Roosevelt days that Potsdam was not going to be like the previous summits.

Difficulty was a common strain that would become more and more palpable as the Conference wore on and even resulted in outbursts like at the end of the twelfth plenary session when Truman brought up the issue of internationalizing certain waterways. The President believed that this would help to lubricate trade and promote peace in political post-war Europe; Stalin, on the other hand, could not have disagreed more.

Truman wanted his proposal to at least be mentioned in the final communiqué, something to which Attlee also agreed. But when Stalin expressed his disapproval, Truman pointed out that this proposal had been discussed during the Conference already and that he was only pressing this one issue.

“Marshall Stalin,” Truman began. “I have accepted a number of compromises during this conference to confirm with your views, and I make a personal request now that you yield on this point…”

“Nyet!” Stalin exclaimed. Then, with emphasis, and in English for the first time all Conference, he repeated:

“No, I say no!”

It was an embarrassing and a profoundly difficult moment that turned Truman beet red.

“I can’t understand that man!” Truman was heard to say. He then turned to Byrnes and said, “Jimmy, do you realize we have been here seventeen whole days? Why, in seventeen days you can decide anything!”

In a letter to his mother, Truman called the Russians the most pigheaded people he had ever encountered. He now realized that they were relentless bargainers who “forever pressing for every advantage for themselves,” as he later said. As much as he might have tried and no matter how much he relied on his Midwestern optimism to help him, Truman could make little or no progress with Stalin.

This then begs the question of whether or not Roosevelt would have done better at Potsdam, or if there would have been more of a favorable outcome in the eyes of the British if Churchill had not left halfway through the Conference. It is hard to say, but it is also a question that Truman must have asked himself several times during and after the summit. Truman knew that he was inexperienced and ignorant when it came to matters of foreign policy. Not ignorant in the sense of being unintelligent – Truman was very intelligent – but ignorant in the sense of not knowing what had really gone on in the previous meetings with Stalin and Churchill, except for what he had read in the minutes from previous conferences and what the likes of William Leahy or Jimmy Byrnes – people who had been in the executive circle for quite some time – had told him. Roosevelt never prepped Truman for the presidency, he never took him under his wing, and never shared anything of significance or importance with him during the eighty-two days that Truman served as his vice president. So Truman knew that he had a whale of a job to do going into Potsdam and everyone else around him knew it too.

But even those who had been in the Roosevelt circle were not so sure if Truman’s predecessor would have done any better getting through to Stalin at Potsdam. Interpreter Chip Bohlen, interestingly, thought that Roosevelt would have been less successful, since, with his personal interest in earlier agreements with Stalin, would have acted more angrily than Truman when faced with Stalin’s intransigence. Along with Bohlen, and others like the United States Ambassador to the Soviet Union, Averell Harriman, and others who were experienced in dealing with the Russians, they thought that Truman had actually done himself well.

“He was never defeated or made to look foolish or uninformed in debate,” Bohlen would write.

And since Stalin and Molotov never attempted any cunning tricks and given the fact that they mostly only held stubbornly to their own line, Truman’s inexperience in diplomacy did not really matter in the end.

Truman left no doubt in his diary that he understood the reality of the Stalin regime when the Potsdam Conference was over.

“It was a police government pure and simple. A few top hands just take clubs, pistols and concentration camps and rule the people on the lower levels.”

Later, Truman would tell his good friend and future Secretary of the Treasury, John Snyder, about a bone-chilling exchange he had with Stalin about the Katyn Forest Massacre of 1940.

When Truman asked what had happened to the Polish officers, Stalin answered coldly, “They went away.”

Despite all the stress, frustration, rancor and serious exhaustion that came from dealing with Stalin and the Soviets, according to Truman’s biographer, David McCullough, “Still-still-Truman liked him.”

Truman would admit years later that he had been naive at Potsdam. He called himself “an innocent idealist” and referred to Stalin as the “unconscionable Russian Dictator.” Yet even then he added:

“And I liked the little son-of-a-bitch.”

–

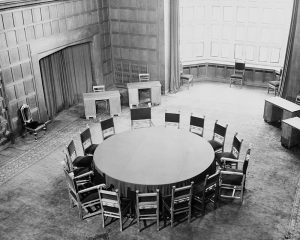

“We will take up the report of the Protocol Committee,” President Truman announced as he opened the thirteenth and final plenary session of the Potsdam Conference at the unusual hour of 10:40PM. All three delegations were prepared to sign off on the final wording of the Potsdam communiqué – essentially a contract spelling out the few agreements the three governments had achieved.

It was clear that the struggle had now come down to the tedious fine points, particularly after Molotov suggested an amendment in a paragraph that described Poland’s western frontier as running from the Baltic Sea through the town of Swinemünde. He wanted to substitute the words “west of” for “through”.

“How far west?” asked Byrnes.

“Immediately west,” suggested Bevin.

“Immediately west will satisfy us,” Stalin affirmed.

“That’s all right,” said Truman.

“Agreed,” said Attlee.

The Red Army had pushed Poland’s western frontier all the way to the Oder River and the Western Neisse River and the Americans and British just accepted it for the time being. Furthermore, Poland was given the southern portion of East Prussia, including the port of Danzig, while the Soviet Union was granted the northern portion. As for free elections in Poland, something for which the British had argued multiple times during the Conference, it was agreed only that they should be held ‘as soon as possible’, which in reality meant the Polish issue remained unresolved.

Meanwhile, Germany would remain divided into four zones under Allied occupation – which was in effect, divided down the middle between East and West. A complete demilitarization of the German state was agreed to and Nazi war criminals were indisputably to be brought to justice in Nuremburg, the city in which they rallied for terror for so many years. And by a complicated formula for reparations, the Soviet Union got the lion’s share – mainly in capital equipment – in view of the fact that the Soviet Union had suffered the greatest loss of life and property during the war. As a result of this rather complicated formula, it will never really be known exactly how much Germany ended up paying in reparations when it was all said and done.

As it might seem as though the Soviets got the most at Potsdam, in some instances Stalin actually did not get everything that was discussed during the Conference. He badly wanted Soviet trusteeship over Italy’s former colonies in Africa – whose topic was deferred to the United Nations – as well as a four-power control over Germany’s industrial area in the Ruhr region – where British and American troops occupied.

Yet, at the end of the day, it was the Western leaders who made the biggest concessions at Potsdam. This was primarily due to the fact that, even before the Potsdam Conference had begun, Stalin had been able to use his army to drive his belt of protection all the way up to 30 miles east of Berlin, use his forces to set up governments sympathetic to Moscow, and consequently use the Red Army to ensure Soviet domination of eastern Europe for the next half century.

Of all those who sat at the negotiating table at Potsdam, William Leahy – President Truman’s Chief of Staff – summed up the Conference the most tellingly:

“My general feeling about the Potsdam Conference was one of frustration. Both Stalin and Truman suffered defeats…The Soviet Union emerged at this time as the unquestioned all-powerful influence in Europe…One effective factor was a decline of the power of the British Empire…With France grappling for a stability that she had not achieved even before the war, and the threat of civil war hanging over China, it was inescapable that the only two major powers remaining in the world were the Soviet Union and the United States…”

The clock had just ticked past midnight. Stalin picked up his pen and signed the communiqué first, followed by Truman, then Attlee.

“I declare the Berlin Conference adjourned – until our next meeting which, I hope, will be in Washington,” Truman announced.

“God willing,” Stalin replied. “The Conference, I believe, can be considered a success.”

The President then thanked the Foreign Ministers and all those who had done so much work, before he said:

“I declare the Berlin Conference closed.”

After all the formal goodbyes had been said and wishes for good health and a safe journey expressed, all three leaders made their own way out of the Cecilienhof Palace with his own entourage.

As for Truman and Stalin, they would never see each other in person ever again.

Leahy further noted in his summary of the Conference:

“Potsdam had brought into sharp world focus the struggle of two great ideas – the Anglo-Saxon democratic principles of government and the aggressive and expansionist police-state tactics of Stalinist Russia. It was the beginning of the ‘Cold War’.”

**

Our Related Tours

To learn more about Potsdam and visit the site of the Potsdam Conference, have a look at our Royal Potsdam tours.

To learn more about the history of Cold War Berlin and life behind the Iron Curtain; have a look at our Republic Of Fear tours.

Bibliography

Byrnes, James (1947). Speaking Frankly. New York: Harper & Brothers. ISBN 978-0-837-17480-8

Cullough, David (1992). Truman. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-86920-5

Fabian, Nadine. “Ein Besuch in der Stalin-Villa in Potsdam.” Märkische Allgemeine. 23 August 2017, https://www.maz-online.de/Lokales/Potsdam/Ein-Besuch-in-der-Stalin-Villa-in-Potsdam

Neiberg, Michael (2015). Potsdam: The End of World War II and the Remaking of Europe. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-07525-6

McBaime, Albert (2017). The Accidental President. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0-544-61734-6

Miscamble, Wilson D (1978). Anthony Eden and the Truman-Molotov Conversations, April 1945

Roberts, Geoffrey (2007). Stalin at the Tehran, Yalta, and Potsdam Conferences

Smyser, William (1999). From Yalta To Berlin: The Cold War Struggle Over Germany. New York: St. Martin’s Press. ISBN 0-312-06605-8

Sternberg, Jan. “Churchill und die lila Plüschmöbel.” Märkische Allgemeine. 13 July 2015, https://www.maz-online.de/Thema/Specials/P/Potsdamer-Konferenz/Villa-Urbig-am-Griebnitzsee.

Truman, Harry S. (1956). Memoirs: Year of Decisions Volume 1. New York: Doubleday.