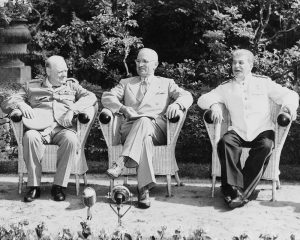

Today marked one week since the Potsdam Conference got underway at Cecilienhof. After all the evening plenary sessions, daytime meetings between the foreign ministers, economic subcommittee meetings, and sessions among the Combined Joint Chiefs of Staff, it is safe to say that negotiations began to wear down the delegations.

Perhaps not so much the heads of state themselves, but the men that worked tirelessly within their respective delegations – who were the driving engine of all the business done at Potsdam – could feel the exhaustion from endless discussions that had resulted in very little progress so far. Great Britain’s chief of Imperial General Staff, Sir Alan Brooke, may have spoken for many when he wrote in his diary:

“It all feels flat and empty. I am feeling very, very worn out.”

It was certainly the complexity of the issues that put agreements on hold day after day. The Americans – and the British for the most part – favored the establishment of a peace treaty with Italy, but Stalin made hay while the sun shined out of this, arguing that if Italy should swiftly get a peace treaty and be granted admission into the United Nations, then the United States and Great Britain should be compelled to extend their enthusiasm and recognize the governments of Bulgaria, Hungary, and Romania at the same time – all areas where the Red Army thoroughly occupied and countries that were being drastically put under the sphere of Soviet influence.

By this point, the Polish question had dominated much of the roundtable talks between the Big Three. Stalin had clashed bitterly with Churchill and Truman over Germany’s borders to the east and believed that Poland should get a large chunk of Germany’s eastern frontier. Since valuable territory – rich in mineral resources – was at stake and given the fact that millions of ethnic Germans lived in the region, so much debate had ensued that Stalin suggested that the Poles, who represented the provisional government in place at that time, come to Potsdam and give their viewpoints on the matters at hand.

And then of course there was Germany itself – the culprit responsible for bringing the Big Three together in the first place. The Americans and the British wanted a complete denazification of the country and then rebuild a democratic and self-supporting Germany that could provide security in Europe. Stalin, on the other hand, disagreed. Twice in the span of his lifetime, his country had fought wars with Germany and therefore felt that a weak Germany was in Russia’s best interest.

Furthermore, economics complicated matters and impeded the negotiations as well. Both Great Britain and the Soviet Union were desperate for money and resources immediately after WWII and both countries were relying on loans from the United States. Truman, on the other hand, had needed to protect American taxpayers and dodge pressure from penny-pinching Republicans, like Senator Arthur Vandenberg of Michigan who called aid disbursement overseas “the most colossal blank check in history”. And Truman was very much aware of this and indeed had the American taxpayer in mind at the fourth plenary session when he said:

“The United States can not, moreover, pour out its resources without prospective return. We want to get satellites on a self-supporting basis. I will not sanction the continued handing out of funds to nations which should be self-supporting. We want to help these nations to become self-supporting.”

And finally, after one week of negotiations, it became clear that the most heated friction between the Anglo-Americans and the Soviets was ideological. While debating the fates of the governments of Austria, Italy, Hungary, Romania, and Bulgaria, and particularly other countries in Eastern Europe, one difference separated Churchill and Truman from Stalin: The United States and Great Britain wanted democratic nations and political stability for the world for reasons of moral righteousness, peace, and economic gain. The Soviets, on the other hand, wanted instability and an imbalance of power for reasons of survival. Stalin was well aware of the fact that his country had either fought in conflicts within or near its own borders around a half a dozen times since Napoleon invaded Russia in 1812. For him, strong nations were threats, while weak ones were not. And he viewed weak countries throughout Eastern Europe as a band of protections against any future power invading Russia again. This disparity between the Anglo-Americans and the Soviets would form the fabric of the Iron Curtain.

–

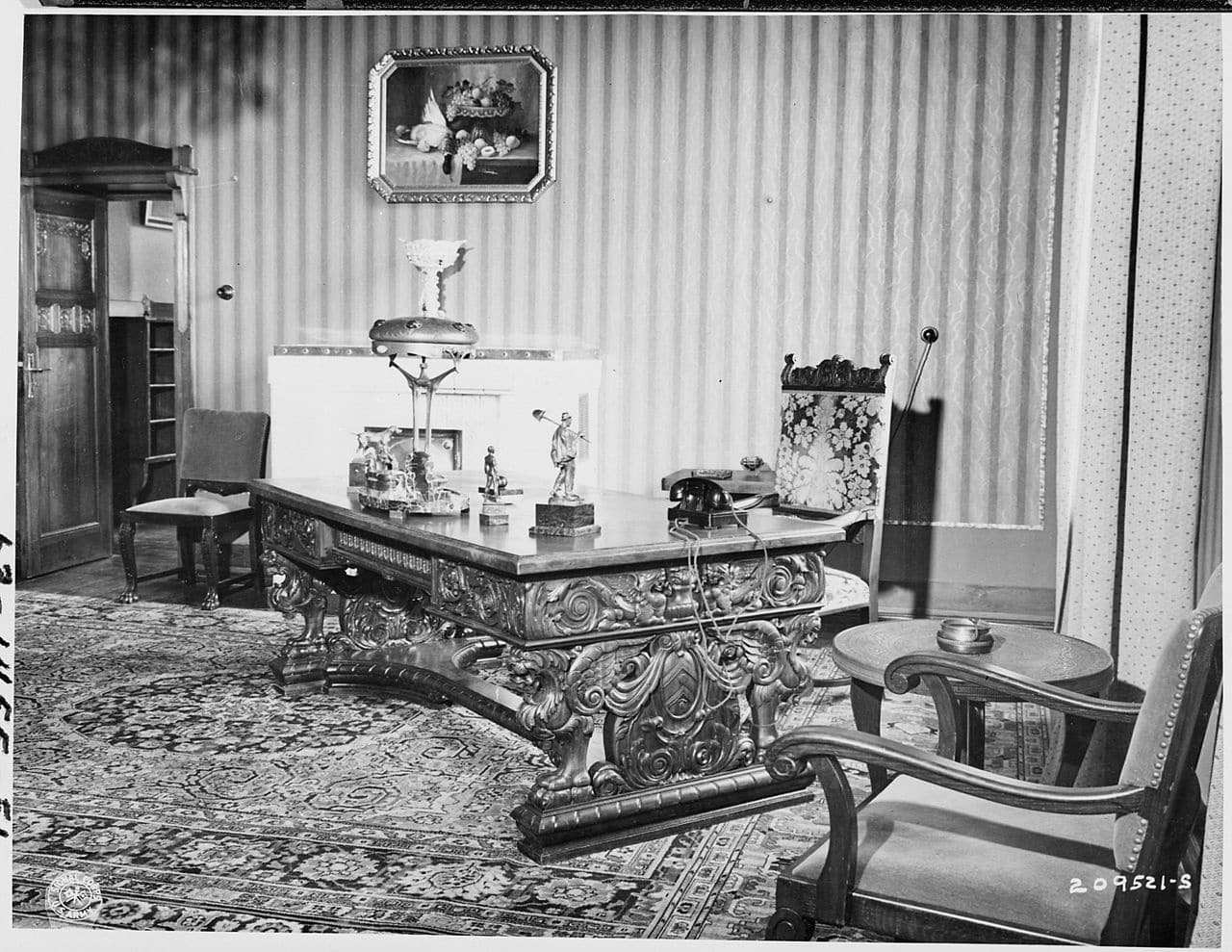

Secretary of War Stimson arrived at the ‘Little White House’ at 9:20am this morning and made his way upstairs to President Truman’s office with another message from Washington:

Top Secret: “Operation may be possible any time from August 1 depending on state of preparation of patient and condition of atmosphere. From point of view of patient only, some chance August 1 to 3, good chance August 4 to 5 and barring unexpected relapse almost certain before August 10.”

President Truman had now been given the confirmation that the atomic bomb was waiting to be released.

At 11:30am – shortly after Stimson left the ‘Little White House’ – Churchill and the British military leaders arrived for a conference of the Combined Chiefs of Staff. The elite British and American military officials offered the Prime Minister and President a document that essentially spelled out the final strategy that would bring the war in the Pacific to an end.

Their report projected that the war would most likely end around mid-November 1946, which was about 16 months from now, if the Japanese would not accept the unconditional surrender demand and if the planned ground invasion were to take place.

Truman would write in his diary:

“I asked General Marshall what it would cost in lives to land on the Tokyo plain and other places in Japan. It was his opinion that such an invasion would cost at a minimum a quarter of a million American casualties.”

Truman had now fully understood what lay at stake. He knew that the atomic bomb was the most terrible thing ever discovered, but he also believed “it can be made the most useful,” as he had recorded in his diary, to bring the war to an immediate end without having to sacrifice the lives of American boys.

It was now time to tell Stalin.

–

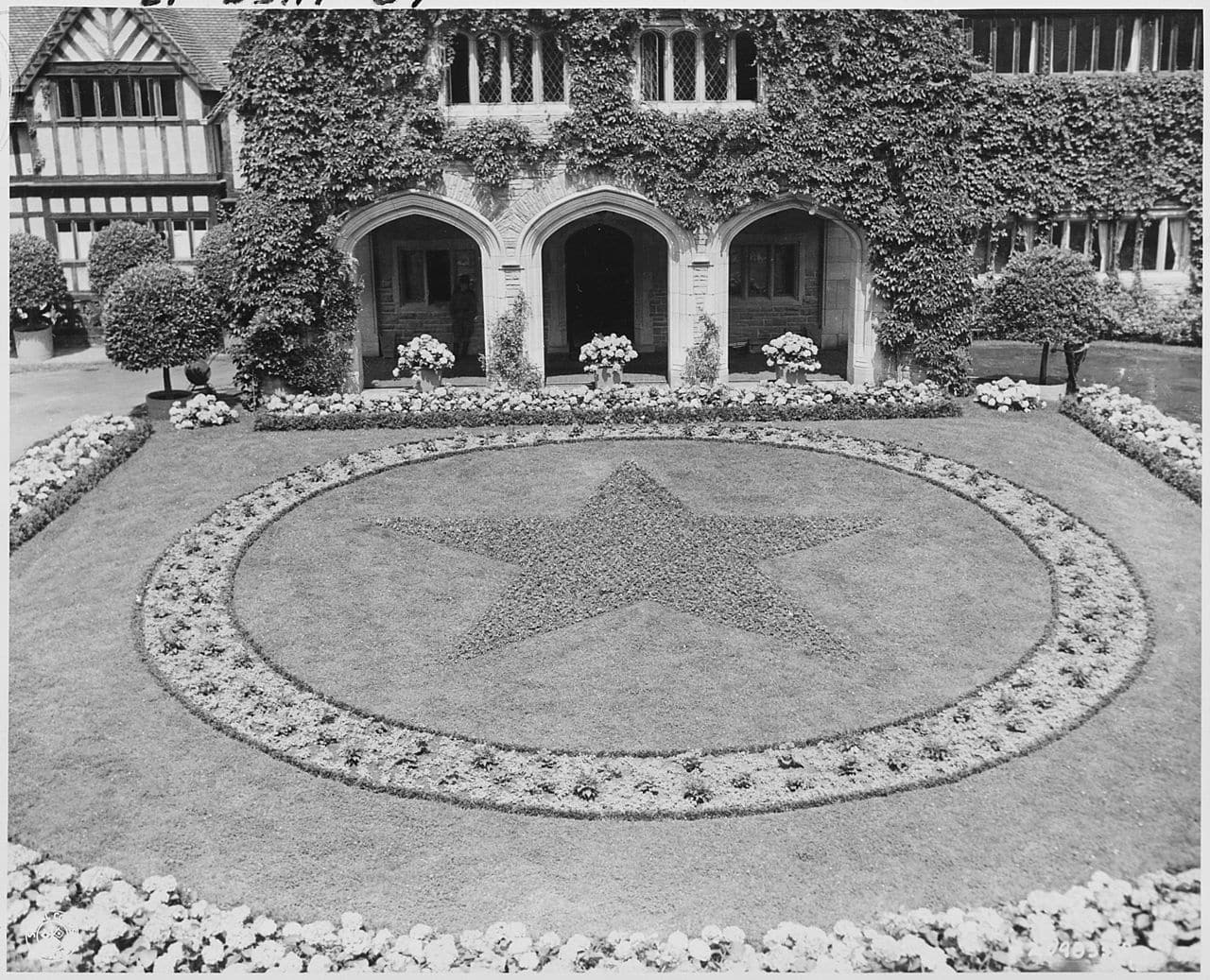

Later on that afternoon, Truman called the eighth plenary session to order at 5:10 PM. Today’s agenda forecasted another run-of-the-mill day of discussions at Cecilienhof with the governments of Eastern Europe and the Polish question being the featured topics.

Stalin was determined to get Churchill and Truman to view the governments of Bulgaria, Hungary, and Romania in the same way they viewed Italy – that is, no favor should be granted to Italy that was not also granted to these states. One essential difference that continued to be pointed out to the Soviets, however, was that all foreign representatives were free to travel about in Italy and report their observations. Since this was not yet possible in Bulgaria, Hungary and Romania, due to the Soviet Army’s occupation in these states, the British and the Americans had a hunch that they were clearly being governed by Soviet puppet regimes or establishing governments that would be undemocratic and sympathetic to Moscow.

“We have been unable to get information, or to have free access to the satellite states of Bulgaria, Hungary, and Romania,” Churchill loudly pointed out. As soon as we have proper access to them, and proper governments are set up we will recognize them – not sooner.

“But you have recognized Italy,” replied Stalin.

Truman spoke up and said:

“The other satellite states will be recognized when they meet the same conditions as Italy has met…We are asking for reorganization of these governments along democratic lines.”

Stalin tried one last time:

“The other satellites have democratic governments closer to the people than Italy.”

Realizing that the word ‘democracy’ carried a different meaning to Stalin than it did to Truman and Churchill, Truman amplified his initial position and replied:

“I have made it clear that we will not recognize these governments until they are reorganized.”

The writing on the wall was clear and all fifteen men sitting at the roundtable in Cecilienhof knew that Italy could not be treated the same as Bulgaria, Hungary and Romania – no matter how much Stalin pushed the issue – because the representatives from Great Britain and the United States could not make their way to these Soviet occupied regions to see firsthand that free democratic governments were being established.

Churchill then brought up Romania as an example:

“Our mission in Bucharest has been practically confined. I’m sure the Generalissimo would be astonished at the catalogue of difficulties encountered by the British mission. An iron fence has come down around them.”

Stalin lashed out with rage and shouted, “They are all fairy tales!”, and maintained that British representatives in Romania were accorded the same courtesies received by Soviet officials in Italy.

Once again, an exhausting round of talks ended with no progress on the fate of the former Axis states, and the American and British delegations could clearly see that Soviet expansion and influence was well underway in Eastern Europe. And at the end of the day, there was nothing that they could directly do, other than sending their own militaries into the region to break through the ‘iron fence’ and then use their physical presence to reorganize those governments along democratic lines. Of course, this would spell out a full-blown conflict with the Soviet Union if they did.

And with that, a very contentious eighth plenary session was adjourned.

–

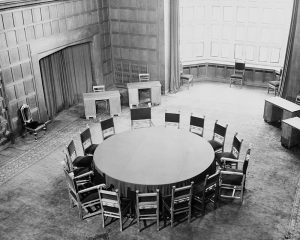

At 7:30pm Truman then made his move.

The President rose from his chair and walked slowly around the conference table to have a private word with the Soviet leader.

Although there is no official description of their conversation on record, there are a few plausible eye-witness accounts that have been published over the years.

First, Jimmy Byrnes gave his account of the conversation in his book ‘Speaking Frankly’, which he wrote some years later:

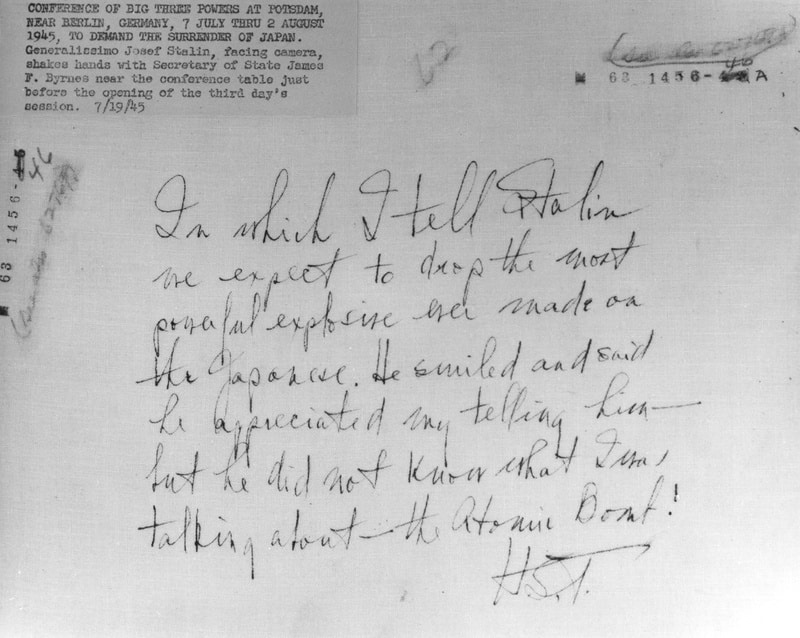

“At the close of the meeting of the Big Three on the afternoon of July 24, the President walked around the large circular table to talk to Stalin. After a brief conversation the President rejoined me and we rode back to the ‘Little White House’ together. He said he had told Stalin that, after long experimentation, we had developed a new bomb far more destructive than any other known bomb, and that we planned to use it very soon unless Japan surrendered. Stalin’s only reply was to say that he was glad to hear of the bomb and he hoped we would use it.”

Second, Truman’s Chief of Staff William Leahy gave his description in his book – of notes and diary entries – called, ‘I was there’:

“At the plenary session on July 24, Truman walked around to Stalin and told him quietly that we had developed a powerful weapon, more potent than anything yet seen in war. The President said later that Stalin’s reply indicated no especial interest and that the Generalissimo did not seem to have any conception of what Truman was talking about. It was simply another weapon and he hoped we would use it effectively.”

Third, Churchill described his account in his book, ‘Triumph and Tragedy’:

“Next day, July 24, after our plenary meeting had ended and we all got up from the round table and stood about in twos and threes before dispersing, I saw the President go up to Stalin, and the two conversed alone with only their interpreters. I was perhaps five yards away, and I watched with the closest attention the momentous talk. I knew what the President was going to do. What was vital to measure was its effect on Stalin. I can see it all as if it were yesterday. He seemed to be delighted.… As we were waiting for our cars I found myself near Truman. ‘How did it go?’ I asked. ‘He never asked a question,’ he replied.”

And finally, straight from the horse’s mouth, President Truman gave his description of their conversation in his book ‘Year of Decisions’ some years later:

“I casually mentioned to Stalin that we had a new weapon of unusual destructive force,” Truman would later write in his diary. “All he said was that he was glad to hear it and hoped that we would make good use of it against the Japanese.”

It did not matter who had the most accurate account of how the conversation went down because there was one observation that everybody clearly saw: Stalin was so bland and seemingly unconcerned about what Truman had just told him. Was it because he thought that Truman was indirectly threatening him given how heated and contentious their talks had just been during today’s plenary session? Maybe Stalin did not clearly understand the importance of what Truman had just said? Or was there another reason?

Whatever the case, at that moment the deed was done. The Americans and the British all assumed that Stalin had no knowledge of the existence of the United States’ atomic science. Yet, as Truman’s interpreter Chip Bohlen later noted:

“I should have known better than to underrate the dictator.”

What we now know is that Stalin had already known more than the British and Americans could have imagined at that time because a German-born physicist and naturalized British citizen named Klaus Fuchs had been providing the Soviets with atomic secrets for some time. And Moscow judged this information from Los Alamos as ‘extremely excellent and very valuable’.

In short, Stalin understood perfectly well what Truman had just told him.

When Stalin got back to his villa in Babelsberg, he instructed Molotov to get in touch with the leader of the Soviet atomic project and tell him that he must “speed things up,” according to Marshal Georgy Zhukov, who was there at Stalin’s villa and realized that the two were talking about the atomic project.

Moreover, there can be no exact date when the Cold War started. However, as historian Charles L. Mee Jr. has pointed out, the nuclear arms race is a different story:

“The Twentieth Century’s nuclear arms race began at the Cecilienhof Palace in Potsdam at 7:30 PM on July 24, 1945.”

**

Our Related Tours

To learn more about Potsdam and visit the site of the Potsdam Conference, have a look at our Royal Potsdam tours.

To learn more about the history of Cold War Berlin and life behind the Iron Curtain; have a look at our Republic Of Fear tours.

Bibliography

Byrnes, James (1947). Speaking Frankly. New York: Harper & Brothers. ISBN 978-0-837-17480-8

Cullough, David (1992). Truman. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-86920-5

Fabian, Nadine. “Ein Besuch in der Stalin-Villa in Potsdam.” Märkische Allgemeine. 23 August 2017, https://www.maz-online.de/Lokales/Potsdam/Ein-Besuch-in-der-Stalin-Villa-in-Potsdam

Neiberg, Michael (2015). Potsdam: The End of World War II and the Remaking of Europe. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-07525-6

McBaime, Albert (2017). The Accidental President. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0-544-61734-6

Miscamble, Wilson D (1978). Anthony Eden and the Truman-Molotov Conversations, April 1945

Roberts, Geoffrey (2007). Stalin at the Tehran, Yalta, and Potsdam Conferences

Smyser, William (1999). From Yalta To Berlin: The Cold War Struggle Over Germany. New York: St. Martin’s Press. ISBN 0-312-06605-8

Sternberg, Jan. “Churchill und die lila Plüschmöbel.” Märkische Allgemeine. 13 July 2015, https://www.maz-online.de/Thema/Specials/P/Potsdamer-Konferenz/Villa-Urbig-am-Griebnitzsee.

Truman, Harry S. (1956). Memoirs: Year of Decisions Volume 1. New York: Doubleday.